Abstract

Nuclear factor κappa-B inhibitors isolated from natural sources that induce apoptosis are promising new agents with anticancer properties. Wortmannin and wortmannolone were isolated from endophytic fungus (Penicillum polonicum) and showed NF-κB inhibitory effects with inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.47 μM and 2.06 μM for wortmannin and wortmannolone, respectively. The activity was compared with rocaglamide (IC50=0.075 μM). The mechanism through which wortmannin and wortmannolone exhibited an attenuating effect on the NF-κB pathway was further evaluated in this study. Wortmannolone showed significant reactive oxygen species (ROS) inducing effects in HeLa cervical cells. The ROS inducing effect was concentration dependent, and the ROS generating activity was comparable with daunomycin, a potent chemotherapeutic agent. The findings suggested that the elevated formation of ROS was partially involved in the induction of apoptosis in treated cells. Potent cytotoxic and apoptotic effects were also displayed in MDA-MB-231 hormone independent breast cancer cells when treated with wortmannolone (IC50=3.79 nM). Thus, wortmannolone, a furanosteroid from an endophytic fungus, is a promising agent for further drug development.

Keywords: Reactive oxygen species, apoptosis, furanosteroids, wortmannolone, K-Ras and NF-κB mediated pathways, synergy, combination index

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress can induce various biological processes including oxidative modifications of redox-sensitive transcription factors and may be involved in ROS mediated cell death (Ozben 2007). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are mediators that induce apoptosis in cancer cells. Furthermore, induction of ROS is associated to other intracellular effects on the epidermal growth factor (EGF) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) pathways. Herein, the effect of wortmannolone on ROS, the transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and oncogenic KRas was investigated in two different cell lines HeLa cervical cancer cells and MDA-MB-231 hormone-independent cancer cells. The transcription factor NF-κB prevents cancer cells from entering apoptosis and contributes to cancer progression in certain cancers (Darnell 2002). Thus inducing apoptosis selectively in cancer cells through NF-κB inhibition is a strategic approach to develop new anticancer therapies. The activation of NF-κB is responsible for survival signaling, proliferative control, and moreover promotes the resistance of cancer cells to certain tumorigenic agents and chemotherapy (Lerebours et al., 2007) NF-κB is a heterodimer composed by subunits p50 and p65 (Perkins 2007). When inactive, NF-κB is found sequestered in the cytoplasm, bound to subunit IκB. The IκB kinase (IKK) is responsible for the phosphorylation of IκB by which, NF-κB is subsequently released and translocated to the nucleus where it exerts its effects, activating target genes involved in the etiology of the disease. Transcription factor NF-κB is found activated in the nucleus of certain types of cancer cells. The IKK-β and NF-κB are induced in response to inflammatory stimuli e.g. the pro-inflammatory cytokinins and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Yin et al., 2007). As part of our ongoing research program on NF-κB inhibitors with anticancer activity from natural origin we have identified wortmannolone as a potent ROS inducer and as a NF-κB inhibitor.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Fungal material

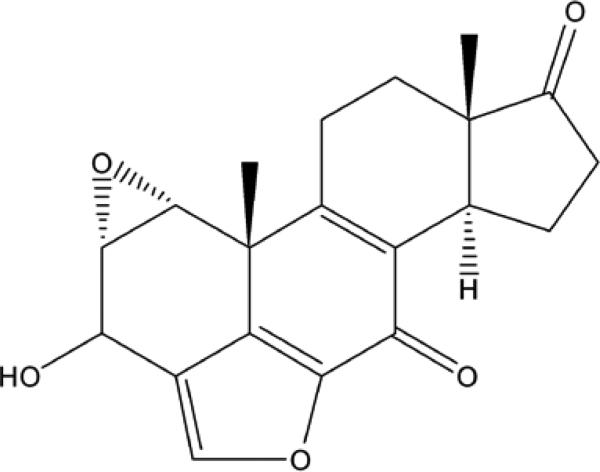

Wortmannin and wortmannolone were previously isolated from Penicillum polonicum (Fig.1) as part of our drug discovery program.

Fig. 1.

Wortmannolone isolated from Penicillum polonicum.

2.2 Cell culture

The HeLa cervical cell line and MDA-MB-231 hormone-independent breast cancer cell line were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA. The cells were cultured in Dubelcco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine calf serum and 10% antibiotic-antimycotic from (Gibco, Rockville, MD). The cells were kept at 37°C and in an atmosphere with 5% CO2. HeLa cells were used for NF-κB ELISA, K-Ras, and ROS-assays, and for western blot analysis.

2.3 Immunoblotting

Experiments were performed following a previously reported protocol with some modifications (Muñoz-Acuña et al., 2012). To observe the effect of wortmanolone on the NF-κB pathway, HT-29 cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes and treated with wortmannolone at five different concentrations (0.008, 0.016, 0.4, 2.0 and 50 μM) and with the positive control, rocaglamide from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY, USA). Cells were incubated for 5h followed by 30 min treatment with or without human recombinant tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (10 ng/ml) from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA). Cells were lysed and whole cell protein lysates were prepared using PhosphoSafe Lysis Buffer from Novagen (Madison, WI, USA).

The protein concentrations were measured by using a Bradford protein assay kit and albumin standard (Thermo Scientific). To determine the protein concentration present in cell lysates and in albumin standard dilutions, absorbance was measured using a Fluostar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtech Inc, Durham, NC). The protein content in cell lysates was extrapolated on the standard curve created for albumin standard. Sample volume containing 20 μg of proteins together with lithium dodecyl sulfate sample loading buffer (LDS) was loaded to Nu-PAGE 10% SDS-PAGE Bis-Tris gels, together with SeeBlue® Plus2 Pre-Stained Standard Ladder from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

The proteins were separated by electrophoresis performed with SDS-PAGE running buffer in a Nu-PAGE XCell SureLock Module (Invitrogen), and transferred to a polyvinyldiene fluoride (PVDF) membrane from Thermo Scientific, using TBS-T buffer (TBS-T)( Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The blots were blocked overnight at room temperature with non-fat dried milk and subsequently probed by primary antibodies (1:1000) against each target protein using 1% BSA in TBS-T. Primary antibodies (anti-NF-κBp65 and p50, anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, and anti-caspase-3) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA, USA) and detected by western blot analysis with HRP conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Conjugated antibodies were detected using a chemiluminescent substrate, Supersignal Femto LumiGLO kit (Thermo Scientific).

2.4 Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) assay

The assay was performed following a previously described procedure (Kim et al., 2010). In brief, HeLa and MDA-MB-231 were seeded in a 96-well plate. Then, cells were treated with wortmannolone (0.028-280 μM), paclitaxel (0.0001-0.1 μM), and daunomycin (0.08-8 μM), followed by 5 hr incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2. Then, cells were either treated or non-treated with H2O2 (1.25 mM) and FeSO4 (0.2 mM) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Afterward, the fluorescent probe DCFH-DA was added to detect intracellular ROS over a period of 2 h. Fluorescence was detected and measured using Fluostar Optima fluorescence plate reader (BMG Lab technologies GmbH, Inc, Durham, NC USA) with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 530 nm. All treatments were performed in triplicate and are representative of at least two different experiments.

2.5 K-Ras assay

Briefly, a 96-well plate was seeded with cell suspension of HeLa cells. The cells were treated with wortmannolone and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. This was followed by the removal of media and cells were washed three times. Then, cells were treated with epidermal growth factor (EGF) at a concentration of 5 ng/ml for 2 min. The cells were lysed and the cell extract was then aliquoted and Ras activity was tested by using RasGTPase Chemi Elisa from Active Motif (Carlsbad CA). Primary H-Ras antibody (1:500) and secondary antibody HRP-conjugated (1:5000) were added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Chemoluminescence solution was added, and the luminescence was read using Fluostar Optima fluorescence microplate reader (BMG Labtechnologies Inc., Durham, NC, USA). Each data point is an average of triplicate readings.

2.6 Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay

The viability of normal colon fibroblast cells was determined using the CCD-112 cell line from ATCC, using a previously published protocol (Pan et al., 2010). Briefly, 10 μL of various concentrations of test samples in 10% DMSO were transferred to 96-well plates along with 190 μL of cells (5 × 104 cells/mL) and incubated for 72 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. The incubation was stopped with the addition of 50 μL cold 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA).

The cells were washed, air-dried, and stained with 0.4% SRB in 1% acetic acid for 30 min at room temperature. Wells were then washed four times with 1% acetic acid, and the plates were dried overnight. Bound dye was solubilized with 200μL Tris base (10 mM), pH 10, for 10 min on a gyratory shaker. A zero-day control was also performed in sixteen wells, incubating at 37°C for 30 min, and processing as described above. Optical density was measured on a micro-plate reader (Bio-tek) at 515 nm and percent survival was calculated using triplicate samples. ED50 values were determined using Table Curve 2Dv4 (System Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

2.7 Cell cycle analysis

Cell death and apoptosis were determined by using propidium iodide (PI) to stain DNA in MDAMB-231 cells. Previous studies demonstrated that the cytotoxicity of wortmannolone ranged from 1.2-5.1 μM (after 72 hr of treatment), depending on the cell line. The MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded on 10 cm plates and treated with wortmannolone (0.10 μM) for 24 h. Cells were then washed with PBS, treated with trypsin EDTA, centrifuged, and re-suspended in PBS. Afterwards, cells were fixed using ethanol (70%), kept on ice for 1h, washed, re-suspended in ice cold PBS, and treated with RNAase (20 μg/mL), followed by 1h incubation at 37°C. Cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) (1.0 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich) and kept in the dark, until the cells were analyzed using BD FACS Canto II at 488 nm.

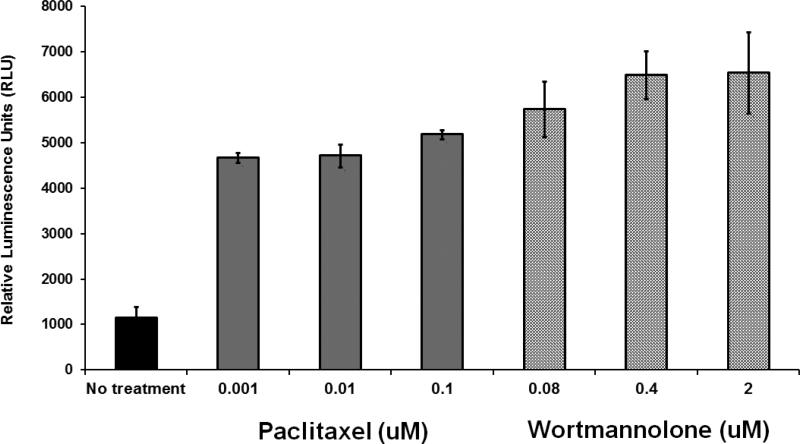

2.8 Caspase 3/7 GLO assay

Caspase-3 and 7 enzymatic activities were measured using the Caspase–Glo3/7 assay from Promega, Madison, WI, USA. HeLa cells were treated with different concentrations of wortmannolone (0.08-2 μM) for 3 h. Paclitaxel (0.0001-0.1 μM) was used as a positive control. Caspase–Glo 3/7 reagent was then added and luminescence was recorded using Fluostar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) at 37°C and enzymatic activity was calculated. Each data point is an average of triplicate readings.

2.9 Calculating combination index (CI)

To determine the synergistic/potentiating effect between wortmannolone and daunomycin, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated at different combination concentrations and the effect was evaluated using the ROS assay. The software CompuSyn® was used for calculating the combination index Chou-Talalay (CI).

3. RESULTS

3.1 NF-κB inhibiting effect of wortmannolone

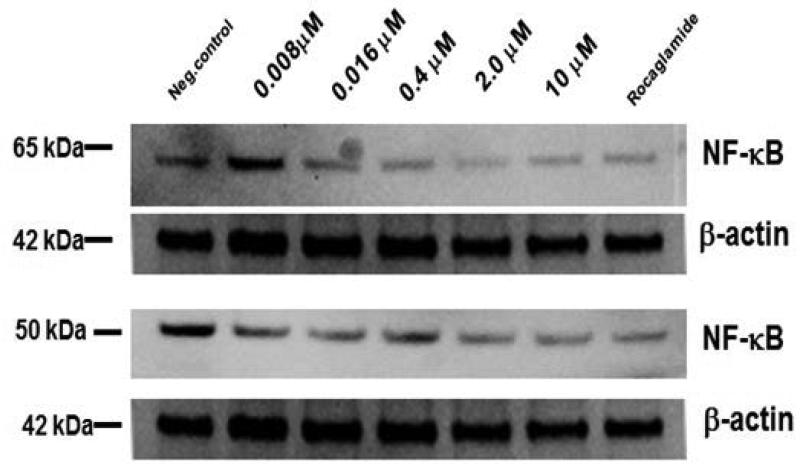

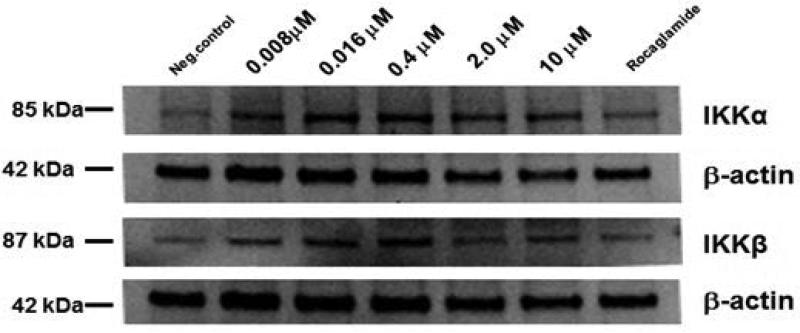

In our ongoing screening for NF-κB inhibitors from natural sources, wortmannin displayed NF-κB inhibitory effect (IC50=0.47 μM) and was compared with rocaglamide (0.08 μM). The structural analog wortmannolone also displayed inhibitory activity (IC50=2.06 μM). The NF-κB inhibitory effect was assessed in the nuclear extract of HeLa cells by measuring the level of binding of subunit p65 (RelA) to the consensus sequence. The attenuating effect on the NF-κB pathway of wortmannolone was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2). The results from western blot showed that NF-κB p65 was downregulated in a concentration-dependent manner in wortmannolone treated cells. The inhibitory effect on p50 and p65 was concentration-dependent. Although the NF-κB subunit p65 and p50 were down-regulated, the upstream mediators IKKα and IKKβ did not appear to be significantly affected by the same treatment (Fig 3) (Idris et al., 2009).

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory activity of wortmannolone on NF-κB p65 and p50. Immunoblot analysis performed on nuclear lysate of HeLa cells showed that wortmannolone suppressed NF-κB activation, and the inhibitory effect was concentration-dependent. β-Actin was used as an internal control to establish equivalent loading.

Fig. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of the effect of wortmannolone on mediators of the NF-κB pathway. Western blot analysis showed that wortmannolone suppresses NF-κB activation. The kinases IKK-α and IKK-β were downregulated in MDA-MB-231 treated cells. β-Actin was used as an internal control.

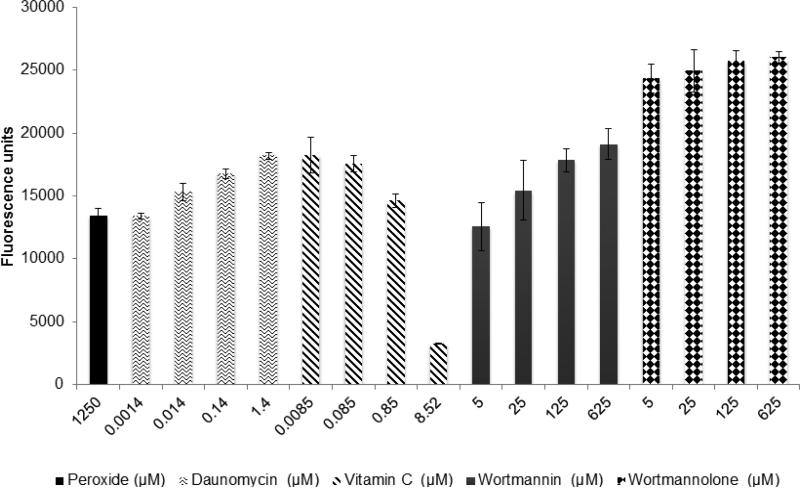

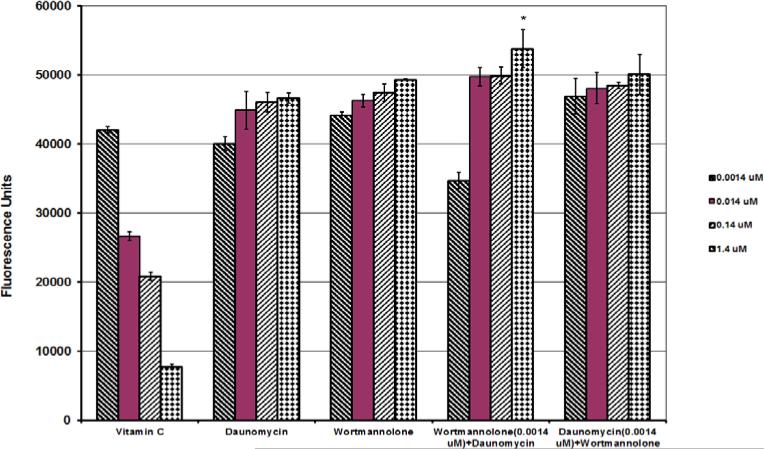

3.2 Intracellular levels of ROS in treated cells

Treatment with the furanosteroids, wortmannin and wortmannolone significantly induced ROS levels in treated cells. Additionally, wortmannolone induced significantly higher intracellular ROS levels compared to the positive control, daunomycin (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of ROS inducing effect of wortmannin and wortmannolone using MDA-MB-231 in the presence of peroxide (H2O2). The cells were treated at four different concentration levels for 5 h. ROS was detected with fluorescent probe DCFH-DA at 485 nm emission wavelength and 530 nm excitation wavelength. In this assay, H2O2 and vitamin C were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and the graph represents the results of two separate experiments. Values represent the means ± SEM from three independent experiments.

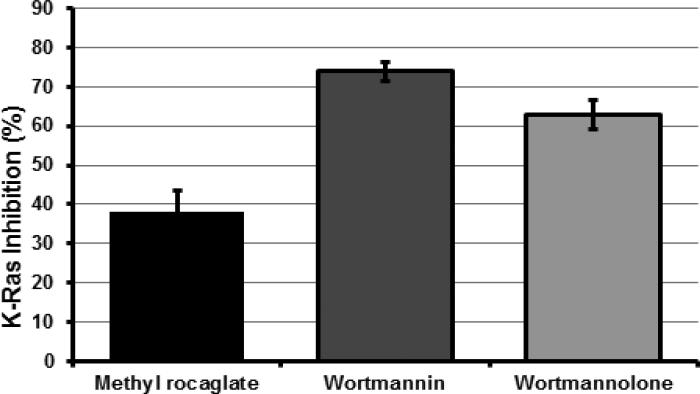

3.3 K-Ras inhibitory effect of wortmannolone

Wortmannin showed 74% inhibition of Ras activation, and wortmannolone showed 63% inhibition against the oncogenic K-Ras target in HeLa cells (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect wortmannin and wortmannolone on the EGFR mediated pathway. The K-Ras inhibition of wortmannin and wortmannolone was tested in HeLa cervical cancer cells. The K-Ras inhibition displayed was 74% for wortmannin and 63% for wortmannolone. The effect was compared with the positive control, methyl rocaglate (38%).

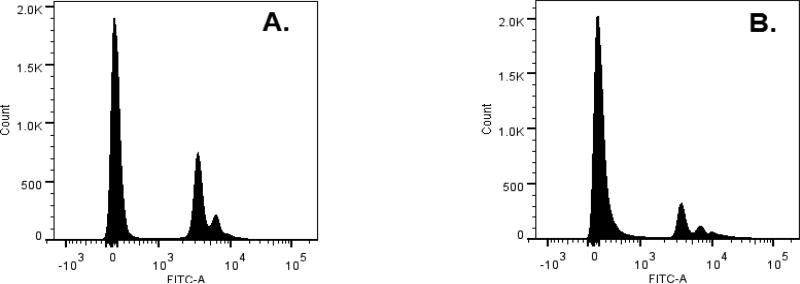

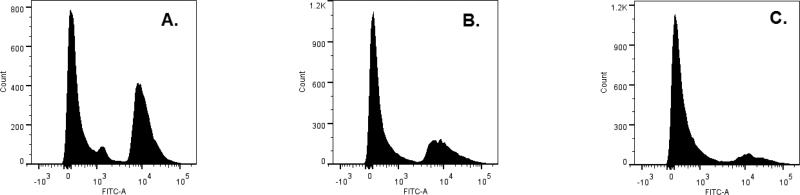

3.4 Cell cycle arrest and apoptosis

The apoptotic effect of wortmannolone in treated HeLa cells was confirmed by investigating the cell cycle distribution and DNA content by cell sorting analysis. In untreated cells the population of cells in sub G1-phase was 61.9%, and the population in G1-phase was 23.7% (Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, in wortmannolone treated HeLa cells the population of cells in sub G1-phase was 76.1%, and in G1-phase the population was 11.7% (Fig. 6B). Similar effects were found in treated MDA-MB-231 cells. The untreated cells showed a population of 49.2% in sub G1-phase, and 38.3 % of cells in G1-phase (Fig. 7A). Treatment with wortmannolone (0.1 μM) showed 67.2% in sub G1-phase, and 26.9% cells in G1-phase. Treatment showed a reduced population of cells in G1-phase (Fig. 7B). The effect of the combination composed of daunomycin (0.0014 μM) and wortmannolone (1.4 μM) in MDA-MB-231 hormone independent cells showed 82.6% cells in sub G1-phase, and 12.4% of MDA-MB-231 cells in G1-phase. This indicated that wortmannolone displayed anti-proliferative effects in the hormone-independent MDA-MB-231 cell line (Fig. 7C). Apoptosis was caspase-3 mediated in treated cells (Figs. 8 and 9)

Fig. 6.

DNA histogram for HeLa cells and accumulation of apoptotic cells in the apoptotic region. A. Untreated cells showed a population of 61.9% cells in sub G1-phase and 23.7% of HeLa cells in G1-phase. B. Treatment with wortmannolone (0.1 μM) showed 76.1% in sub G1-phase, and 11.7% in G1-phase. Treatment showed a reduced population of cells in G1-phase when compared to untreated HeLa cells.

Fig. 7.

DNA histogram for MDA-MB-231 cells and accumulation of apoptotic cells in the apoptotic region. A. Untreated cells showed a population of 49.2% in sub G1-phase, and 38.3 % of MDA-MB-231 cells in G1-phase. B. Treatment with wortmannolone (0.1 μM) showed 67.2% in sub G1-phase, and 26.9% cells in G1-phase. Treatment showed a reduced population of cells in G1-phase. C. Effect of combination treatment composed of daunomycin (0.0014 μM) and wortmannolone (1.4 μM) in MDA-MB-231 hormone independent cells showed 82.6% cells in sub G1-phase, and 12.4% of MDA-MB-231 cells in G1-phase.

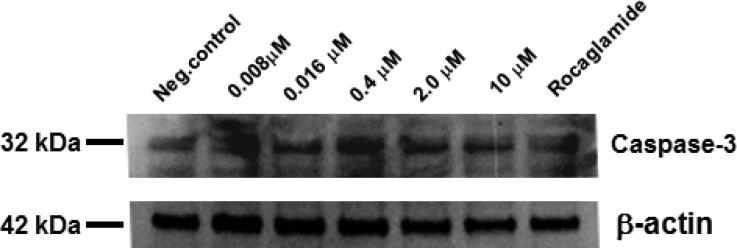

Fig. 8.

Wortmannolone displayed dose-dependent caspase-3 inhibition in treated HeLa cells. Caspase-3 activity was induced in a concentration dependent manner after treatment with wortmannolone, in comparison with untreated HeLa cervical cancer cells when tested in the Caspase–Glo3/7 assay.

Fig. 9.

Immunoblot analysis of the effect of wortmannolone on the mediators of the caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway. Analysis showed that wortmannolone suppresses caspase-3. β-Actin was used as an internal control.

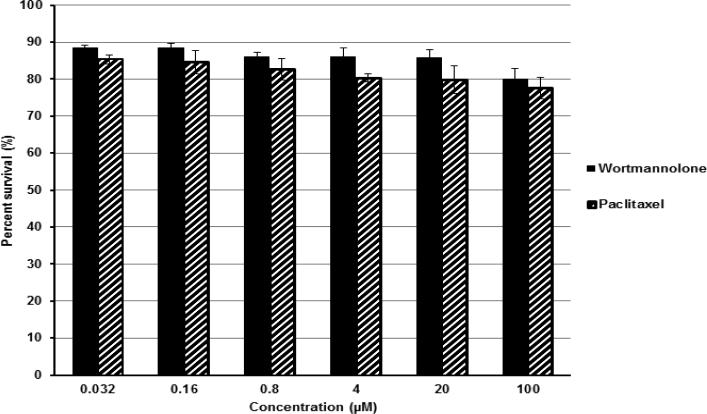

3.5 Wortmannolone cytotoxicity and synergistic effects in combination treatment

Cytotoxicity in the MDA-MB-231 cells was tested using the SRB assay. The results showed a potent cytotoxic effect (IC50=3.72 nM), compared with the positive control paclitaxel IC50=0.93 nM. Wortmannolone showed lower cytotoxic effect though when compared to paclitaxel on the CCD-112 normal colon fibroblast cell line, suggesting that wortmannolone exhibit a higher selectivity towards cancer cells (Fig. 10 and 11). In the ROS assay the combination treatment, showed that wortmannolone synergized with daunomycin when the cells were treated with daunomycin (1.4 μM). Treatment with daunomycin (1.4 μM) produced 52.1% ROS, in combination with a low dose of wortmannolone (0.0014 μM) the amount of ROS increased to 101.5% (Fig. 10.). The ROS inducing effects were significantly higher (p>0.05) for the combination treatment. In addition, the evaluation of the biological effect and possible synergistic effect, obtained from the combination of two pharmacological agents was calculated following the previously presented method by Chou-Talalay (Chou-Talalay, 1984).

Fig. 10.

Synergistic effect of wortmannolone and daunomycin. The intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in HeLa cervical cancer cells after 5 h of treatment was detected with fluorescent probe DCFH-DA at 485 nm emission wavelength and 530 nm excitation wavelength. In this assay, H2O2 and vitamin C were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The effects were compared with the positive control, daunomycin. The combination of wortmannolone at a low dose of 0.0014 μM and the highest dose of and daunomycin (1.4 μM) significantly enhanced the levels of ROS, compared to the positive control daunomycin (1.4 μM). Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and the graph represents the results of two separate experiments. Values represent the means ± SEM from three independent experiments.

Fig. 11.

Effect of wortmannolone and paclitaxel on normal colon fibroblast cells CCD-112 cell line. The cells were treated for 72 h and stained with SRB. Then, absorbance was measured to assess the number of viable cells. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and the graph represents the results of two separate experiments. Values represent the means ± SEM from three independent experiments.

4. DISCUSSION

Endophytic fungi are promising sources of bioactive metabolites for medicinal, pharmaceutical, agriculture and biotechnological uses. The chemical diversity of secondary metabolites produced by fungi make them promising new source of anticancer agents by optimizing new natural product leads through semi-synthetic derivatization. The yield of active metabolites can be optimized by genetic modifications and biotechnological methods. Similarly, the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis microspora now produces Taxol® in mycelial culture (Strobel et al., 1996). The aim of this study was to characterize the cellular responses and mechanism of action, and to study the signal transduction pathways affected in cancer cells by the furanosteroids from Penicillum polonicum, an endophytic fungus of Taxus fuana; wortmannolone in comparison with its natural analog wortmannin. Wortmannin and wortmannolone were first isolated and identified from Penicillium wortmannii (Grove et al., 1986). Immunoblot analysis was performed to evaluate the effects of wortmannolone on the mediators of the NF-κB pathway in HeLa cells (Figs. 2 and 3). Subsequently, the effects on the redox status of treated cells were studied and results suggested that the ROS inducing effect inhibited NF-κB activation downstream (Fig 4). Although both furanosteroids, wortmannin and wortmannolone induced ROS in the treated cells in a concentration-dependent manner, wortmannolone was more potent than wortmannin in inducing ROS in HeLa cervical cancer cells (Fig. 4). The potent ROS inducing effects of the furanosteroids wortmannin and wortmannolone, could be attributed to the presence of an epoxide function that might lead to more extensive interaction with active target. Wortmannolone lacks two methyl group compared with the structure of wortmannin, which would suggest that there are less hydrophobic interactions in the binding site of the target. The furan ring in both wortmannin and wortmannolone is essential for reactivity and ROS increasing effect; however further synthetic furanosteroid derivatives would confirm the structure-activity relationship related to the potent ROS generating capacity. To further investigate the mechanism of action, we tested the effect of wortmannin and wortmannolone on the EGFR mediated pathway, and in particular the effect on the upstream target, K-Ras was assessed. The withdrawal of growth factors and the inhibition of the EGFR pathway had previously been reported to induce apoptosis in malignant cells. In this study it was found that the oncogenic target K-Ras was inhibited in cells treated with furanosteroids, wortmannin and wortmannolone (Fig. 5). The K-Ras activates several pathways downstream, which are involved in the proliferation and differentiation of cancer cells, and the oncogenic mutations of Ras are reported to be present in 39% of human cancers (Herrmann et al., 1996) and fungal metabolites with inhibitory effect might reveal to be promising lead structures for this target. K-Ras is a key regulator involved in tumorigenesis, reported to be constitutively active, and the downstream signaling affects mediators of the NF-κB pathway. The results suggested that elevated ROS levels affected GTPase activity of K-Ras in treated HeLa cells. This indicated that the treatment with wortmannolone and furanosteroids interfere with EGFR stimulation, in cancer cells with oncogenically transformed K-Ras. In summary, the increased levels of ROS and oxidative stress lead to affected oncogenic regulators both upstream (K-Ras) and downstream (NF-κB). To our knowledge this is the first time that wortmannolone is reported to significantly induce the ROS pathway and to consequently affect the EGF/K-Ras pathway, and the NF-κB pathway, which are constitutively active in HeLa cervical cancer cells.

The induced ROS levels and the oxidative stress generated in HeLa cells treated with wortmannolone were further evaluated using cell cycle analysis. An increased population of cells in sub G1-phase was detected in treated cells, compared with untreated cells. This indicated that a cell cycle block had occurred in G1-phase (Fig. 6), confirming the antiproliferative effects of the furanosteroid, wortmannolone. The induced enzymatic caspase-3 activity indicated that wortmannolone exhibited caspase-mediated apoptotic effects in cancer cells (Fig. 9). This was confirmed by the down-regulation of procaspase-3 (32 kDa) (Fig. 10). In addition, the effect of wortmannolone was evaluated in hormone-independent MDA-MB-231 using fluorescence cell-sorting analysis. In treated MDA-MB-231 cells, the cell-cycle arrest was identified in G1-phase. The triple-negative breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-231, are hormone-independent and lack estrogen- (ER), progesterone- (PgR), and the growth factor receptors (HER-2) (Mur et al., 1998). MDA-MB-231 cells are also deficient in p53 suppressor gene (Hui et al., 2006). The MDA-MB-231 cells are aggressive, metastatic and do not respond to existing pharmacological treatments such as, growth receptor antagonist e.g. herceptin and estrogen antagonists, and thus there is still need for more effective targeted treatment for this type of malignancies (Tate et al., 2013). The combination treatment of daunomycin (1.4 μM) with wortmannolone (0.0014 μM) performed in hormone-independent and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 cells results suggested that low concentration of wortmannolone synergizes with daunomycin in treated cells (Fig. 7).

Combination therapy is an alternative mode of treatment in cancer therapy with the purpose of increasing efficacy and minimizing the incidence of side effects and toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents. The combined ROS generating effect of wortmannolone and daunomycin was also evaluated in HeLa cervical cancer cells (Fig. 10). The combination treatment was compared to if the cells were treated with daunomycin alone, an effective anticancer agent currently used in the pharmacological treatment of acute leukemia. The combination index method was employed to determine the effect displayed by the combination treatment composed of daunomycin (1.4 μM) and wortmannolone (0.0014 μM). These findings suggested that the two agents act through different intra-cellular pathways. The synergistic effect displayed between daunomycin and wortmannolone increased the ROS-generating capacity in treated HeLa cancer cells. The effect of the combination of daunomycin and wortmannolone was evaluated both using cell flow cytometry and in the ROS assay, suggesting that daunomycin and wortmannolone act by affecting different cellular targets. The two agents alter different cellular pathways and caused apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells. Thus the high antiproliferative activity (IC50= 3.79 nM) of wortmannolone in MDA-MB-231 cell suggested that optimized derivatives of the compound would exhibit a promising therapeutic potential against hormone-independent breast cancer cells, by inducing oxidative stress in susceptible malignant cells.

Another goal of combination chemotherapy is to improve the effect in chemoresistant cancer cells. The findings presented here suggested that low concentration levels of wortmannolone analogs may increase the efficacy of existing treatments and might have beneficial effects, against multi-drug resistant cell types. Moreover, the combination of wortmannolone derivatives and daunomycin reduced the effective dose of daunomycin and thus also reduce the incidence of side-effects due to the existing treatment. The optimal anticancer therapy requires the combination of agents targeting multiple pathways, to avoid and minimize toxicity. The study identifies the synergistic activity and therapeutic potential by daunomycin and wortmannolone in a combination therapy format. We have compared the effects of wortmanolone with paclitaxel on the viability of normal colon fibroblasts (Fig. 11). The cytotoxicity displayed was lower than the effect observed with paclitaxel, suggesting that wortmannolone derivative might exhibit less toxic effects against normal cells than paclitaxel. This indicated that combination treatment would possibly reduce the incidence of side-effects and that new furanosteroids analogs obtained from endophytic fungi, are promising agents that may increase the efficacy of existing chemotherapy, and lead to more positive outcomes in the treatment of cancer. In particular the results suggest that patients with hormone-independent breast cancer might benefit in the future from the development of new anticancer agents containing the furanosteroid scaffold.

CONCLUSION

Wortmannolone inhibits Hela cervical and MDA- MB-231 breast cancer cell proliferation. Wortmannolone significantly induced ROS in treated cells as well. Additionally, wortmannolone had an attenuating effect in a concentration-dependent manner on the upstream mediators IKKα and IKKβ, which resulted in lower levels of expression of NF-κB p65 and p50 in treated cancer cells. The ROS inducing effects and the NF-κB inhibitory effects decreased the activity of the nuclear p65, affected cell cycle progression, and induced cell death in cancer cells. Moreover, our findings suggest that ROS induction by wortmannolone sensitizes cancer cells to apoptosis. Wortmannolone is also a promising agent for combination therapy since it synergistically induces further ROS when in the presence of daunomycin. Wortmannolone, therefore, represents a potential chemotherapeutic agent with antitumor effects from natural origin with significant ROS induction effects. Thus, optimization of the potential of wortmannolone might lead to a more effective anticancer agent, specifically for the treatment of breast cancer to be used alone or in combination therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We greatly acknowledge the financial support from the Ohio State University and the program project grant P01 CA125066-S1 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, to carry out this work. Authors would like to thank Dr. Mark E. Drew and Dawn Walker for facilitating the use of a BD FACS Canto II instrument.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest was disclosed by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blight MM, Fredrick Grove J, Viridin Part 8.′ Structures of the Analogues Virone and Wortmannolone. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin. Trans.1: Organic and Bio-Organic Chemistry. 1986;7:1317–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darnell JE., Jr. Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:740–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann C, Horn G, Spaargaren M, Wittinghofer A. Differential interaction of the ras family GTP-binding proteins H-Ras, Rap1A, and R-Ras with the putative effector molecules Raf kinase and Ral-guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:6794–800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui L, Zheng Y, Yan Y, Bargonetti J, Foster DA. Mutant p53 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells is stabilized by elevated phospholipase D activity and contributes to survival signals generated by phospholipase D. Oncogene. 2006;25:7305–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Idris AI, Libouban H, Nyangoga H, Landao-Bassonga E, Chappard D, Ralston SH. Pharmacologic inhibitors of IkappaB kinase suppress growth and migration of mammary carcinosarcoma cells in vitro and prevent osteolytic bone metastasis in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2339–47. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JA, K Lau E, Pan L, Carcache De Blanco EJ. NF-kappaB inhibitors from Brucea javanica exhibiting intracellular effects on reactive oxygen species. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:3295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerebours F, Vacher S, Andrieu C, Espie M, Marty M, Lidereau R, Bieche I. NF-kappa B genes have a major role in inflammatory breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell. 1996;86:147–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muñoz-Acuña U, Wittwer J, Ayers S, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, Carcache de Blanco EJ. Effects of (5Z)-7-Oxozeaenol on the oxidative pathway of cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2665–2671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mur C, Martinez-Carpio PA, Fernandez-Montoli ME, Ramon JM, Rosel P, Navarro MA. Growth of MDA-MB-231 cell line: different effects of TGF-beta(1), EGF and estradiol depending on the length of exposure. Cell Biol Int. 1998;22:679–84. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1998.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozben T. Oxidative stress and apoptosis: impact on cancer therapy. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007;96:2181–96. doi: 10.1002/jps.20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan L, Kardono LB, Riswan S, Chai H, Carcache de Blanco EJ, Pannell CM, Soejarto DD, McCloud TG, Newman DJ, Kinghorn AD. Isolation and characterization of minor analogues of silvestrol and other constituents from a large-scale re-collection of Aglaia foveolata. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1873–8.8. doi: 10.1021/np100503q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perkins ND. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-kappaB and IKK function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 2007;l8:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slee EA, Harte MT, Kluck RM, Wolf BB, Casiano CA, Newmeyer DD, Wang HG, Reed JC, Nicholson DW, Alnemri ES, Green DR, Martin SJ. Ordering the cytochrome c-initiated caspase cascade: hierarchical activation of caspases-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, and -10 in a caspase-9-dependent manner. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:281–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strobel G, Yang X, Sears J, Kramer R, Sidhu RS, Hess WM. Taxol from Pestalotiopsis microspora, an endophytic fungus of Taxus wallachiana. Microbiology. 1996;142(Pt 2):435–40. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tate CR, Rhodes LV, Segar HC, Driver JL, Pounder FN, Burow ME, Collins-Burow BM. Targeting triple-negative breast cancer cells with the HDAC inhibitor Panobinostat. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;14:R79. doi: 10.1186/bcr3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker EH, Pacold ME, Perisic O, Stephens L, Hawkins PT, Wymann MP, Williams RL. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition by wortmannin, LY294002, quercetin, myricetin, and staurosporine. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:909–19. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin Y, Chen X, Shu Y. Gene expression of the invasive phenotype of TNF-alpha-treated MCF-7 cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2009;63:421–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]