Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder in which hemoglobin S (Hb S) predominates in red blood cells. It is considered a significant public health issue in Brazil.1–3

Sickle cell anemia (SCA, Hb SS) is the most common subtype of SCD in the world. Although its clinical course is variable, patients with SCA generally have the most severe phenotype. SCD also includes the heterozygous combination of Hb S with other hemoglobin variants (Hb SC, Hb SD-Punjab, and others). The combination of Hb S with β thalassemia (Hb S/β0 and Hb S/β+ thalassemia) leads to other subtypes of SCD with a variable relative incidence depending on the ethnic composition of the population.4,5

The relative death rate due to hemoglobin disorders in under five-year-old children all over the world is reported to be 3.4% of all deaths.6 Morbidity and mortality are especially high in developing countries.7 Even in developed countries, SCD is still a significant cause of mortality, particularly in adolescents and adults.8–10

There are only two newborn-screening cohort studies in Brazil, which have reported the death rate for children with SCD. In both studies, it was very high compared to figures reported in developed countries. In Minas Gerais,3 the crude death rate for 1396 children (all subtypes) diagnosed in a seven-year period was 5.6%. The Kaplan–Meier estimated probability of death at five years of age for children with Hb SS or Hb S/β0 thalassemia was 10.6% (standard error: 1.4). In Rio de Janeiro,1 the crude death rate for 912 children (all subtypes) in a ten-year period of newborn screening was 4.2%. The main causes of death in both cohorts were infection (including acute chest syndrome which in children is indistinguishable from pneumonia) and acute splenic sequestration.

Unfortunately, the crude death rate for the newborn cohort in Minas Gerais has not significantly decreased over the years. In a recent report that will be published in the Jornal de Pediatria (RJ),11 the death rate in the last seven-year period of observation was 5.12% compared to 5.43% (p-value = 0.72) in the first seven years of the study.

In this issue of the Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia (RBHH), Lima et al.12 analyze trends in mortality and hospital admission rates for patients (not only children) with SCD in a 14-year period, comparing the data before and after the introduction of a newborn screening program in Maranhão, a northeastern state in Brazil. The total number of recorded hospital admissions increased from 128 in the first seven-year period (‘pre-newborn screening’ – 1999–2005) to 840 in the ‘post-newborn screening’ period (2006–2012). The rate of hospitalization relative to the total population in Maranhão increased from 0.315 (pre) to 1.832 (post) per 100,000 persons, indicating a ratio 5.82 times higher and showing a growth in trend (p-value = 0.04). The median age at admission dropped from 11.4 years to 8.7 years (p-value = 0.0002). The mortality rate increased from 0.115 to 0.216, 1.88 times higher (p-value = 0.59 – non-significant). The median age at death increased from ten years to 14 years (p-value = 0.67 – non-significant). In conclusion, the authors state that “the key reason for the apparent paradox of increased mortality and hospitalization rates after the implementation of neonatal screening is the increased ‘visibility’ of sickle cell disease”.

The invisibility of SCD is also evident when the authors compare the hospitalization rate for SCD in Maranhão (1.832) with those in Bahia (1.8), São Paulo (6.0), and Rio de Janeiro (7.0).13 Considering the relative proportion of Black people in the total population, Lima et al. have estimated that the expected number of patients should be very similar in these states (9–11 thousand) and so the hospitalization rate should be about the same, which is empirically not true. In this comparison, the lower hospitalization rate for Maranhão and Bahia relative to Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo is due not only to under-reporting of patients (the ‘invisible’ disease), but also, probably, to lower level of health care for patients with SCD in these poorer states demonstrating “the social differences that exist between regions in Brazil”.12

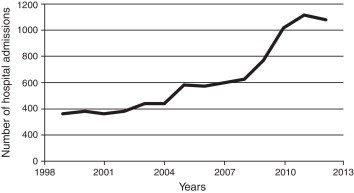

In Minas Gerais, we have observed two other pieces of evidence of the invisibility of SCD. In the aforementioned study,11 the inclusion of the word sickle (“falciforme”) on the death certificates of children who were known to be patients with SCD since birth (they tested positive in the newborn screening and had been followed up in the Fundação Centro de Hematologia e Hemoterapia de Minas Gerais – HEMOMINAS) increased from the incredible figure of 42.1% in the first seven-year period to a still low figure of 60.5% in the last period. Similar to the data of Maranhão, we have observed a steep increase in hospital admissions (n = 8028) for children and adults registered in the Hospital Information System (SIH) of the Brazilian National Health Service (SUS) from 1999 to 2012 (data not published yet – Figure 1).14

Figure 1.

Hospital admissions for children and adults with the main diagnosis of sickle cell diease (CID D57) in Minas Gerais, Brazil, from 1999 to 2012 (n = 8028).

In conclusion, continuous educational programs directed to health professionals and to families and patients with SCD should be boosted in order to increase the ‘visibility’ of the disease and to decrease the mortality and morbidity caused by it. Also, as we have previously stated,3 “the [Brazilian] Ministry of Health's program to provide integrated healthcare for people with SCD is an ideal toward which patients, their families and the professionals involved in treating them must work in order to achieve the objective of improving the current living conditions and health status of these people”.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Gabriela Ricardo de Aquino Santos, Fernanda Araújo Avendanha, Gabriella Oliveira Lima e Ana Paula Pinheiro Chagas Fernandes for having shared original data preliminary displayed at the XXIII Semana de Iniciação Científica da UFMG (reference # 14).

Footnotes

See paper by Lima et al. on pages 12–16.

References

- 1.Lobo C.L., Ballas S.K., Domingos A.C., Moura P.G., do Nascimento E.M., Cardoso G.P. Newborn screening program for hemoglobinopathies in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:34–39. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pereira S.A., Brener S., Cardoso C.S., Proietti A.B. Sickle cell disease: quality of life in patients with hemoglobin SS and SC disorders. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2013;35(5):325–331. doi: 10.5581/1516-8484.20130110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandes A.P., Januario J.N., Cangussu C.B., Macedo D.L., Viana M.B. Mortality of children with sickle cell disease: a population study. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2010;86(4):279–284. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinn C.T. Sickle cell disease in childhood: from newborn screening through transition to adult medical care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(6):1363–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serjeant G.R. The natural history of sickle cell disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(10):a011783. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Modell B., Darlison M. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(6):480–487. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.036673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGann P.T. Sickle cell anemia: an underappreciated and unaddressed contributor to global childhood mortality. J Pediatr. 2014;165(1):18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamideh D., Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999–2009) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(9):1482–1486. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanni E., Grosse S.D., Yang Q., Olney R.S. Trends in pediatric sickle cell disease-related mortality in the United States, 1983–2002. J Pediatr. 2009;154(4):541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y., Liu G., Caggana M., Kennedy J., Zimmerman R., Oyeku S.O. Mortality of New York children with sickle cell disease identified through newborn screening. Genet Med. 2014 doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.123. September 25 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabarense A.P., Lima G.O., Silva L.M., Viana M.B. Characterization of death of children with sickle cell disease diagnosed by Newborn Screening Program and followed prospectively. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2014.08.006. November 6 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lima A.R., Ribeiro V.S., Nicolay D.I. Trend analysis of mortality and hospital admissions for patients with sickle cell disease before and after the newborn screening program in Maranhão. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2015;37(1) doi: 10.1016/j.bjhh.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loureiro M.M., Rozenfeld S. Epidemiologia de internações por doença falciforme no Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2005;39(6):943–949. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102005000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos G.R., Avendanha F.A., Lima G.O., Fernandes A.P., Viana M.B. XXIII Semana de Iniciação Científica da UFMG, 2014, Belo Horizonte. Anais eletrônicos da XXIII Semana de Iniciação Científica da UFMG. 2014. Avaliação das internações das crianças com doença falciforme triadas pelo Programa de Triagem Neonatal de Minas Gerais em unidades hospitalares do Sistema Único de Saúde, no período de 1998 a 2012. [Portuguese] [Google Scholar]