Abstract

Context:

Anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) has no effective treatment, resulting in a high rate of mortality. We established cell lines from a primary ATC and its lymph node metastasis, and investigated the molecular factors and genomic changes associated with tumor growth.

Objective:

The aim of the study was to understand the molecular and genomic changes of highly aggressive ATC and its clonal evolution to develop rational therapies.

Design:

We established unique cell lines from primary (OGK-P) and metastatic (OGK-M) ATC specimen, as well as primagraft from the metastatic ATC, which was serially xeno-transplanted for more than 1 year in NOD scid gamma mice were established. These cell lines and primagraft were used as tools to examine gene expression, copy number changes, and somatic mutations using RNA array, SNP Chip, and whole exome sequencing.

Results:

Mice carrying sc (OGK-P and OGK-M) tumors developed splenomegaly and neutrophilia with high expression of cytokines including CSF1, CSF2, CSF3, IL-1β, and IL-6. Levels of HIF-1α and its targeted genes were also elevated in these tumors. The treatment of tumor carrying mice with Bevacizumab effectively decreased tumor growth, macrophage infiltration, and peripheral WBCs. SNP chip analysis showed homozygous deletion of exons 3–22 of the PARD3 gene in the cells. Forced expression of PARD3 decreased cell proliferation, motility, and invasiveness, restores cell-cell contacts and enhanced cell adhesion. Next generation exome sequencing identified the somatic changes present in the primary, metastatic, and primagraft tumors demonstrating evolution of the mutational signature over the year of passage in vivo.

Conclusion:

To our knowledge, we established the first paired human primary and metastatic ATC cell lines offering unique possibilities for comparative functional investigations in vitro and in vivo. Our exome sequencing also identified novel mutations, as well as clonal evolution in both the metastasis and primagraft.

Every year in the United States, approximately 38 000 patients are diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma representing approximately 1% of all human malignant diseases (1). Most thyroid carcinoma patients have differentiated tumors which are amendable to therapy. Anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) accounts for less than 2% of all the thyroid malignancies, with a grave prognosis (2). These tumors are extremely aggressive, and are resistant to radiation therapy and conventional chemotherapy. Individuals with ATC have an average 5-year survival rate of <10%, with a median survival of 4–6 months (3). Novel effective approaches are clearly needed for the treatment of ATCs, including targeted therapy.

Establishment and careful analysis of ATC cell lines should provide the foundation for these advancements. RNA array and candidate gene studies have identified genetic alterations in RET, p53, RAS, BRAF, and β-catenin genes in ATC (4). These studies begin to bring into focus the therapeutic targets of ATC. Next generation sequencing allows the comparison of genomic changes in multiple samples taken from the same individual to delineate the genetic basis for tumor progression and metastasis (5).

We established both primary and metastatic ATC cell lines from the same patient and also a primagraft which was serially passaged for > 1 year in NSG mice without in vitro culture. Using RNA expression arrays, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chip analysis and deep exome sequencing, we identified novel genomic abnormalities and potential treatment targets for ATC. Differential mutational frequencies in the metastasis and primagraft compared with the primary tumor suggest that secondary tumors may arise from a minority of the cells within the primary tumor.

Materials and Methods

Patient history

A 71-year-old Caucasian male was diagnosed with a multinodular goiter at age of 62. He underwent multiple thyroid biopsies, which demonstrated benign adenomatous nodules. At the age of 67, he underwent additional biopsies because of the growth of one nodule. At age 70, the patient developed prostate cancer and underwent a prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. The lymph nodes in the region of the prostate were free of disease. During a staging evaluation at the age of 71, multiple pulmonary nodules were found, that had not been present on a chest CT scan performed 6 months earlier. A PET/CT scan demonstrated multiple PET-positive lung lesions, neck nodes, and a 4 × 6 cm mass in the thyroid gland. A fine needle aspiration of the thyroid mass showed poorly differentiated malignant cells. His white blood cell (WBC) count was elevated at 20 000/uL (normal 4000–11 000/μL) with 81% PMN and an absolute PMN count of 16 400/uL. He underwent a thyroidectomy and central compartment lymph node dissection, which revealed a 3.5 cm ATC that was locally invasive and which also involved two of the 21 lymph nodes. Pathological staging of ATC was pT4bpN1aM1. Immunohistochemistry showed the absence of the expression of S-100 and TTF-1 and the presence of keratin (AE1/AE3). The patient died 3 months following surgery. The diagnosis was established on commonly accepted clinical, laboratory, and histological criteria at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The study subject gave his informed consent for our study (IRB # Pro000067\95).

Establishment of ATC cell line

Thyroid tumor and lymph node were obtained at surgery from the patient and immediately processed. Specimens were minced into small pieces and applied gently against a 40 μm filter. The filter was washed with RPMI media containing 10% FBS, and the flow-through was collected by centrifugation. The pellets were plated on culture dishes. In vitro cell lines were established from the primary thyroid tumor (OGK-P) and the metastatic lymph node (OGK-M). In addition, filtered cells from the lymph node were directly inoculated into the peritoneal cavity of NSG mice without in vitro culture. Forty-two days after the initial seeding, the cavity was opened and clumps of cells were harvested and divided into two halves. One half was cultured on dishes as the first generation of OGK-NSG cells; the other half (1 × 105 to 1 × 107 cells in 200 μL of PBS) was injected in the flanks of NSG mice and transferred as primagrafts for 19 times (> 80 weeks).

Patient samples, cell culture, conditional medium and antibodies, transfection and generation of stable cells, short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, as well as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chip analysis, microarray analysis, exome capture, massively parallel sequencing and analysis of whole exome sequencing data, proliferation assay, migration, invasion and cell adhesion assay, colony formation assay, quantitative real-time PCR, Western blot analysis, immunohistochemistry, murine xenograft studies are described in the Supplemental Material and Methods (6–17). qRT-PCR primer sequences were detailed in Supplemental Table 11.

Statistical analysis

For in vitro and in vivo experiments, we evaluated the statistical significance of the difference between two groups by the two-tailed Student t-test and two-way ANOVA. Asterisks in the figures indicate significant differences of experimental groups in comparison to controls (* P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001). Data points in figures represent the means ± SD.

Results

Establishment of novel ATC cell lines

Surgical specimens from the primary anaplastic thyroid cancer and lymph node metastasis were established in tissue culture (OGK-P and OGK-M, respectively). Cell lines were considered to be established after 15 passages. Cell lines have maintained an in vitro culture for more than 36 months (3 years). Doubling time of the OGK-P and OGK-M is 23 and 18 h, respectively, as measured by the online doubling time calculator (Supplemental Table 1). The metastatic ATC tissue was also established directly in NSG mice as a primagraft (OGK-primagraft), which was serial passaged (19 times) for over 1 year in these NSG mice (Figure 1A). For the initial primagraft (first primagraft), 1 × 105 cells from patient lymph-node were injected into the peritoneal cavity of NSG mice without in vitro culture. On day 42, the tumor volume was 739.2 mm3 (largest and smallest diameter of the tumor was 20 and 8.4 cm). The primagrafts were serially passaged every month for one and half years. No metastasis was observed in the lungs, liver, and spleen of the tumor bearing mice, but the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) policies did not allow primagrafts to grow more than 1.5 cm.

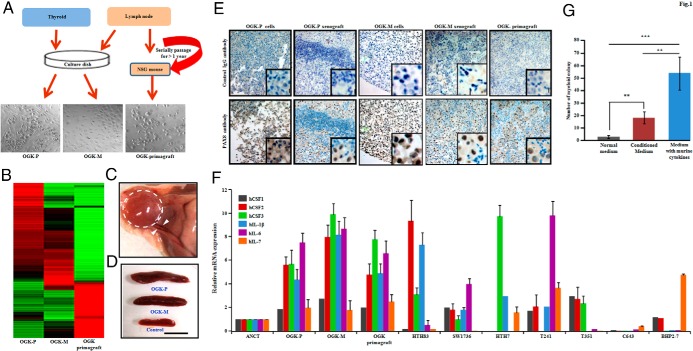

Figure 1.

Establishment of a primary (OGK-P) and metastatic (OGK-M) ATC cell lines, as well as a primagraft (OGK-primagraft) from the metastatic ATC, and features of these cells. A, Methodological approach used for generating ATC cell lines and primagraft from the same patient. The lymph-node metastatic lesion was also established directly in NSG mice as a primagraft and passaged only in the mice for > 1 year. B, Cluster analysis of microarray data of thyroid cancer cells. Expression data established a total of 389 genes with twofold expression that was unique to either OGK-M and/or OGK-primagraft cells compared to OGK-P. Green and red color represents lower higher expression, respectively. The gene list is provided in Supplemental Table 10. C, Representative photograph showing sc tumor formation of OGK-P ATC cell line in athymic nude mice (dotted circle) with abundant blood vessels entering and surrounding the tumor (arrowhead). D, Athymic nude mice growing either OGK-P or OGK-M xenografts showed larger spleens (mean weight of the spleens were 0.18 g in OGK-P and 0.28 g in OGK-M) compared to control mice (mean weight 0.09 g in control). E, Immunohistochemistry of PAX8 in OGK-M cells from either cultured dish or xenograft tumor. PAX8 displayed positive (brown color) staining in the nucleus. PAX8 negative, small cells in xenograft tumors were neutrophils and macrophages infiltrating the tumor. F, Real-time PCR analysis showing expression levels of cytokines [CSF1 (M-CSF), CSF2 (GM-CSF), CSF3 (G-CSF), IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-7] in OGK-P, OGK-M, and OGK-primagraft and other ATC and papillary (BHP2–7) thyroid cell lines compared to normal thyroid. Results expressed as a ratio to GAPDH mRNA and mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments done in triplicates. G, Methylcellulose colony assay using condition media of OGK-M cells. Murine bone marrow cells were grown in Methocult plus 10% conditioned media for 6 days. Results showed mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments done in triplicates. **, P ≤ .01(Student's t-test).

Features of the ATC cells and the primagrafts

STR profiling data showed that OGK-P, OGK-M, OGK-primagraft, and patient DNA are almost identical (Supplemental Table 2), thus genetically linking the cell lines and primagraft to the patient. Microarray analysis showed a total of 389 genes with twofold expression unique to either OGK-M cells and/or OGK-primagraft compared to OGK-P (Figure 1B, Supplemental Table 10). SNP chip analysis of the OGK-P (Supplemental Figure 1A), OGK-M cell lines (Supplemental Figure 1B), and OGK-primagraft (Supplemental Figure 1C) showed predominantly a trisomy of many chromosomes as summarized in Supplemental Table 3. Of note, two regions of all three samples had loss of one arm of chromosome 10p and 17p and duplication of the other arm. Concerning 17p, loss of one chromosomal arm and duplication of the other resulted in a homozygous mutation of the TP53 gene. Focal homozygous deletion at 10p11.21 containing the PARD3 gene occurred in these cell lines.

OGK-P and OGK-M cell lines were injected sc in athymic nude mice; large tumors were evident within 2 weeks with prominent blood vessels (Figure 1C). By the 28th day, peripheral WBC count, especially neutrophils, markedly increased (> fivefold) in these tumor bearing mice (Supplemental Table 4). These mice developed ∼ two- to threefold enlargements of their spleens (Figure 1D) with myeloid metaplasia, and no tumor cells were observed in the spleens. Immunohistochemistry of xenograft tumors showed positive staining for alpha smooth muscle actin (SMA), vimentin, keratin, and mucin 1 (Supplemental Table 5). The OGK-P and OGK-M cell lines, xenografts, and OGK-primagraft cells were examined for thyroid specific genes, such as, the transcription factor 1 (TTF1), thyroglobulin (TG), and paired box gene 8 (PAX8). Immunohistochemistry showed that these were positive (strong nuclear staining) for PAX8, but negative for TTF1 and TG (18, 19) (Figure 1E, Supplemental Table 5). Both TG and TFF1 have been reported to be strongly expressed in normal thyroid tissue and often completely lost in ATC (20). The xenograft tumors were markedly infiltrated with neutrophils (Myeloperoxidase-positive) and macrophages (F4/80-positive) (Supplemental Table 5).

Cytokine and growth factor production in ATC cells

Since splenomegaly and blood neutrophilia developed in the mice carrying both the cell line explants and primagrafts, expression levels of cytokines were measured in these tumors. Relative mRNA expression of CSF1, CSF2, CSF3, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-7 was higher in OGK-P, OGK-M, and OGK-primagraft as well as other ATC cell lines including HTH83, SW1736, HTH7, T241, T351 cells (measured by real time PCR) (Figure 1F and Supplemental Table 6) compared to BHP2–7 cells (papillary thyroid cancer) and normal thyroid cells. Both qPCR and microarray data revealed that expression of cytokines and their receptors were higher in metastatic cells compared to primary cells. In addition, committed myeloid stem cells from wild-type murine bone marrow proliferated and differentiated in methylcellulose into neutrophils and macrophages when cultured in 10% conditioned media from OGK-M cells consistent with hematopoietic cytokines present in the conditioned media (Figure 1G).

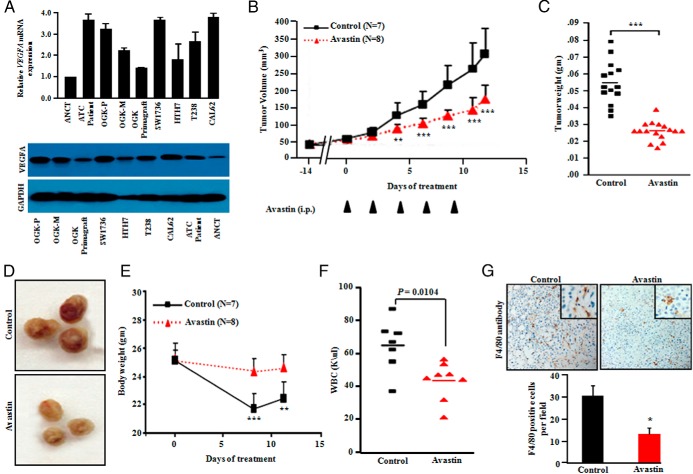

Bevacizumab treatment of mice carrying the ATC xenograft tumors (OGK-M)

Both real time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Western blot data showed higher expression of VEGFA, both at the transcriptional and protein levels in ATC cell lines and patient samples compared to adjacent noncancerous tissue (ANCT) (Figure 2A). Moreover, we observed relatively higher expression of VEGFA in OGK-P cells compared to OGK-M and OGK-primagraft (Figure 2A and Supplemental Table 7). Bevacizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, which suppresses angiogenesis by binding and inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A (VEGFA). Bevacizumab is an FDA approved antibody for treatment of several malignancies, such as glioblastoma and metastatic colorectal, lung, renal, ovarian, and breast cancers (21, 22). Bevacizumab was given every other day intraperitoneally (IP) to mice carrying OGK-M xenografts. The antibody prevented tumor growth in the mice who received the therapy starting 1 day after tumor inoculation (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B). Peripheral blood WBC, neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils in the Bevacizumab-treated group were significantly lower than the tumor bearing control mice receiving diluent. These latter mice had much larger tumors (Supplemental Figure 2, C and D). In another series of experiments, ATC xenografts were grown for 14 days before beginning Bevacizumab treatment (5 mg/kg, three times a week for five courses). These mice treated with Bevacizumab showed significantly decreased tumor volumes (P < .001) (mean tumor volume 150.3 ± 48.0 mm3 compared with control 300.0 ± 86.3 mm3) (Figure 2B). Tumor weights of Bevacizumab-treated mice also decreased compared to the control group (Figure 2, C and D). Tumors in the control group had a very vascular capsule surrounding the tumor (Figure 2D). These control mice also had significant (P < .001) weight loss (Figure 2E) and elevated WBC counts (Figure 2F) compared to Bevacizumab-treated mice. Tumor infiltration with F4/80 positive cells (macrophages) was significantly greater in control tumors compared to Bevacizumab treated tumors (Figure 2G).

Figure 2.

Bevacizumab (anti-VEGFA) treatment of mice inhibits growth of their ATC xenografts. A, Real-time PCR analysis and Western blot showed strong expression of VEGFA mRNA and protein in human ATC cells (OGK-M, OGK-P, OGK-primagraft, SW1736, HTH7, T238, CAL62) and ATC tissue samples compared to adjacent noncancerous tissue (ANCT) samples. B, OKG-M cells (1 × 106) were sc implanted into both flanks of NSG male mice (2 tumors per mouse). After 14 days, palpable tumors were noted, and animals were blindly randomized into 2 groups: 1 group received Bevacizumab (5 mg/kg, 3 times/week for 12 days), whereas the control group received PBS solution. Tumor diameters were measured using a vernier caliper, and tumor volumes were calculated by the formula V = π/6 × Dl × Ds (2), where V is volume, Dl is the largest diameter, and Ds is the smallest diameter. Tumor volumes were significantly smaller in Bevacizumab-treated mice. **, P ≤ .01; ***, P ≤ .001. C, Weights of dissected tumors at the end of the experiment. **, P ≤ .01; ***, P ≤ .001 (Student's t-test). D, Representative dissected tumors; note greater vascular invasion (deep red color) in the control tumors. E, Body weight of Bevacizumab-treated mice was greater than the PBS treated control mice. Data represent mean ± SD of 16 experimental and 14 control tumors. **, P ≤ .01; ***, P ≤ .001 (Student's t-test). F, Bevacizumab-treated mice showed significantly lower peripheral blood WBC counts than PBS control mice. G, Immunohistochemistry for F4/80 (macrophage stain) in dissected tumors showed Bevacizumab-treated tumors had fewer macrophages infiltrating the tumors. Results showed mean ± SD of 4 different tumor sections. **, P ≤ .01; ***, P ≤ .001 (Student's t-test).

PARD3 gene is homozygously deleted, and forced expression of PARD3 reduced cellular growth, motility, and invasion, as well as cell-cell junctions

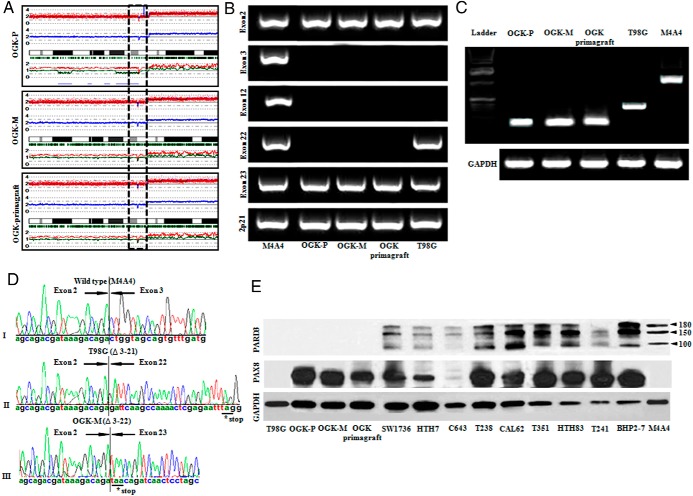

Homozygous deletion of the PARD3 gene (chromosome 10p11.21) was detected in OGK-P and OGK-M cell lines and OGK-primagraft by analyzing their SNP chip data (Figure 3A). For validation, all exons of PARD3 were examined using PCR primers spanning each exon using genomic DNA of OGK-P, OGK-M cell lines and OGK-primagraft. No PCR products of the PARD3 gene were observed between exons 3 and exon 22 for all three cell sources (Figure 3B). M4A4 cells (wild-type for PARD3) and T98G (PARD3 homozygous deletion between exon 3 and exon 21) (23) were used as controls. In addition, RT-PCR and nucleotide sequencing of OGK-P and OGK-M cell lines and OGK-primagraft showed an absence of wild-type PARD3 mRNA and fusion of the deletion-flanking exons (Figure 3, C and D). PARD3 protein expression was not detected in the OGK-P, OGK-M, OGK-primagraft, and T98G cells (negative control) by Western blot (Figure 3E). Interestingly, five of eight ATC cell lines had very low expression of PARD3 compared to M4A4 (wild type for PARD3, positive control) and the papillary thyroid cancer cell line (BHP2–7) (Figure 3E). We analyzed the TCGA thyroid data, composed of 486 thyroid cancer samples. A total of 19.13% (94/486) of the thyroid carcinoma samples had down-regulation of PARD3 mRNA and one sample contained a missense mutation (L51W) of the gene (Supplemental Figure 5). Taken together, these observations suggest that during thyroid carcinogenesis a decreased expression of PARD3 often occurs.

Figure 3.

Intragenic PARD3 deletion in anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines. A, SNP chip tracing of chromosome 10. Upper line: red dots are SNP sites representing total copy number (CN). Middle line: blue line is an average of copy number and indicates gene dosage. Green bars are heterozygous SNP calls. Lower line: red and green lines show allele-specific copy number (AsCN). Dashed box encompasses homozygous deletion at chromosome 10p11.21 (PARD3) in OGK-P, OGK-M cell lines, and OGK-primagraft. B and C, PCR using gDNA and RT-PCR using cDNA confirmed genomic deletion between exon 3 and 22 in OGK-P, OGK-M cell lines, and OGK-primagraft. M4A4 (breast cancer, wild type PARD3) and T98G (glioblastoma, PARD3 deletion: exon 3–21). GAPDH was used as a loading control. D, Sequencing of the PCR products: (top panel), M4A4 (breast cancer, PARD3 wild-type); (middle panel), T98G (glioblastoma, PARD3 deletion between exon 3 and 21); (lower panel), OGK-M (PARD3 deletion between exons 3 and 22), leading to a frameshift, [stop codon (*)]. E, Western blot of PARD3 showed loss of PARD3 expression in the T98G, OGK-P, OGK-M cell lines, and OGK-primagraft, as well as low expression in ATC cell lines: SW1736, HTH7, C643, and T241. PARD3 antibody specifically recognizes a band of 180, 150, and 100 kDa corresponding to PARD3 protein. PAX8 expression was also examined and GAPDH was a loading control.

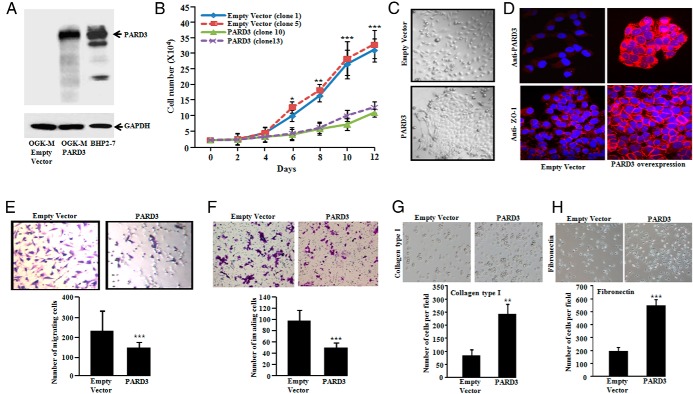

Stable clones of OGK-M cells expressing either a PARD3 expression vector or empty vector were established. Ectopic expression levels of PARD3 protein in OGK-M were very similar to PARD3 endogenous levels present in BHP2–7 cells (wild type PARD3) (Figure 4A), suggesting that our forced expression of PARD3 clones were near physiological levels. PARD3 expressing cells had significantly (P < .001) slower growth compared to control cells (Figure 4B) and acquired clear cell-cell junctions and a tile structure in culture, while OGK-M cells with an empty vector grew more independently of each other (Figure 4C). Zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1, a marker of cellular tight junctions) was noted on the cell-cell junctions of OGK-M cells stably expressing PARD3, whereas no staining was observed with an empty vector (Figure 4D). Moreover, forced expression of PARD3 significantly (P < .001) suppressed motility and invasiveness of OGK-M cells compared to those without PARD3 (Figure 4, E and F).

Figure 4.

Forced expression of PARD3 slows proliferation, alters cell morphology, reduces migration and invasion, and restores cell adhesion. A, Western blot showed restoration of PARD3 expression in OGK-M cells (constitutive deletion of PARD3) stably transduced with PARD3 expression vector (GAPDH, loading control) and endogenous level of PARD3 in BHP2–7 cells (wild type PARD3). B, Restoration of PARD3 expression in OGK-M cells slows their growth. Cells were plated at 1 × 104 cells per well in six well plates in triplicates. Cell proliferation was measured by counting cells over a 10-day period. PARD3 (clones 10 and 13) were separate clones expressing PARD3 and empty vector (clones 1 and 5) were separate clones containing an empty vector. Results showed mean ± SD of 4 different tumor sections. **, P ≤ .05; **, P ≤ .01; ***, P ≤ .001 (Student's t-test). C, Stable expression of PARD3 in OGK-M resulted in enhanced cell-cell contact [lower panel (PARD3) compared to empty vector control cells (upper panel)]. D, Forced expression of PARD3 (right panels) in OGK-M relocalizes ZO-1 to cell-cell contacts [red fluorescence shows PARD3 (top, right) and ZO-1 (bottom, right) expression]. E, Cell motility was measured using Boyden chamber assay. Forced expression of PARD3 reduced the number of migrated OGK-M cells compared to empty vector control cells (left panels). F, Forced expression of PARD3 decreased cell invasion of OGK-M cells as compared to the empty vector. Data for lower panels of E and F represent mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments done in triplicates (right panels). **, P ≤ .01; ***, P ≤ .001 (Student's t-test). G and H, Ectopic expression of PARD3 protein enhances adhesiveness of the OGK-M cells on collagen type I and fibronectin precoated 24-well plates. Representative phase-contrast pictures showed attachment of the cells to wells coated with collagen type I and fibronectin after performing cell adhesion assay (original magnification, × 100). The results for the lower panels of G and H represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicates. **, P ≤ .01; ***, P ≤ .001 (Student's t-test).

During cell passage, we observed that OGK-M cells with stably forced expression of PARD3 displayed a strong attachment to the tissue culture plates, requiring longer duration to release the cells from the plates compared to empty vector control cells. We, therefore, considered that PARD3 enhanced cell adhesion. To further explore this possibility, ECM cell adhesion assays were performed on plates precoated with collagen type I and fibronectin. As anticipated, the OGK-M cells with ectopic expression of PARD3 showed significantly increased adhesion to the components of extracellular matrix collagen type I (Figure 4G) and fibronectin as compared to empty vector containing cells (Figure 4H). Together, these results suggest that PARD3 acts as a tumor suppressor gene in thyroid cells.

Identification and evolution of coding mutations by whole exome sequencing (WES) of primary and metastatic ATC samples and continuous > 1 year passaged ATC primagraft

WES was performed on genomic DNAs obtained from primary (thyroid) and metastatic (lymph-node) ATC, 1 year primagraft, and germline control from the same patient. Average nucleotide coverage was approximately 164×, and 84% of all targeted bases were read at least 20 times, sufficient for variant calls (Figure 5A and Supplemental Table 8). The ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous mutations was 1:2, consistent with the positive selection that typically occurs with driver mutations. A total of 44 nonsynonymous substitutions and 6 indels affecting the integrity of the open reading frames (ORF) were identified in these three tumors. Sanger sequencing validated 39 (true positive rate = 89.13%) of the nonsynonymous SNVs, and 4 indels (true positive rate = 66.7%) were confirmed. Two SNVs could not be tested because of PCR failure (Supplemental Table 9). TP53 (C277Y) mutation was noted in each of these samples.

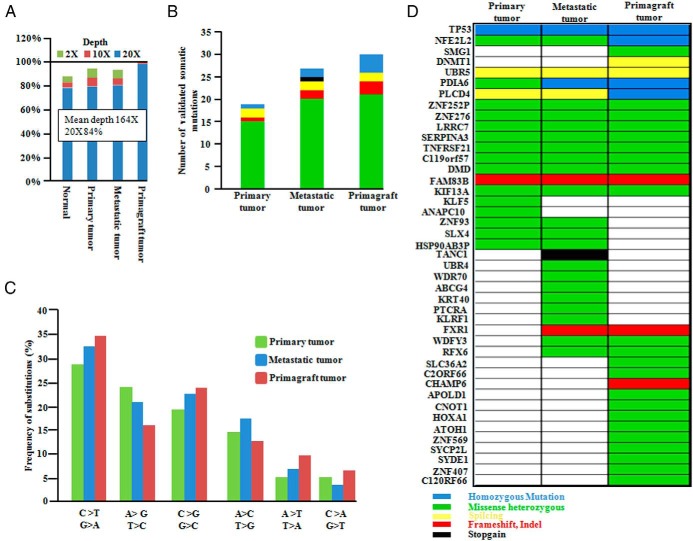

Figure 5.

Mean coverage and mutational analysis of whole exome sequencing in primary and metastatic ATC and primagraft ATC cells as compared to the patient's germline control sample. A, Coverage of the target region and mean depth is plotted. B, Number and type of somatic mutations in primary and metastatic ATC, as well as primagraft. (The color-key for the mutational subtype is placed in the lower right of Figure 5.) C, Frequency of substitution in each tumor. D, Representation of full spectrum of mutations in different genes in primary, metastasis, and primagraft. All mutations were validated by capillary sequencing. DNA for patient's germline control was from a disease-free pelvic lymph node removed at prostectomy.

A total of 43 somatic mutations in primary, metastatic, and primagraft cells were verified using Sanger sequencing, a mutation rate comparable to those of other solid tumors (24). The total number of somatic mutations was higher in the metastatic tumor and primagraft compared to the primary tumor (Figure 5B). Similar to the other cancers, C > T transitions were the most common mutations found in primary and metastatic tumor cells and the primagraft (Figure 5C). Moreover, an increase in A.T > C.G and C.G > G.C transversions occurred in the metastatic tumors and primagraft (Figure 5C). Notably, an increased A.T > C.G transversion rate has also been observed in cases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (25).

Homozygous TP53 mutations were present in the primary and metastatic ATC samples and primagraft cells. Both PLCD4 (R325Q) and NFE2L2 (W8G) missense mutations progressed from being heterozygous in the primary and metastatic ATC to homozygously deleted in the primagraft. Also, the PDIA6 (A339G) gene was heterozygously mutated in the primary ATC, and homozygously mutated in the metastatic ATC and the primagraft (Figure 5D, Supplemental Figure 3). The SIFT test was used for the prediction of damaging mutations, and most of the validated mutation scores indicated that those on the list were damaging mutations (Supplemental Table 9). DNMT1 and SMG1 genes were only mutated in the primagraft.

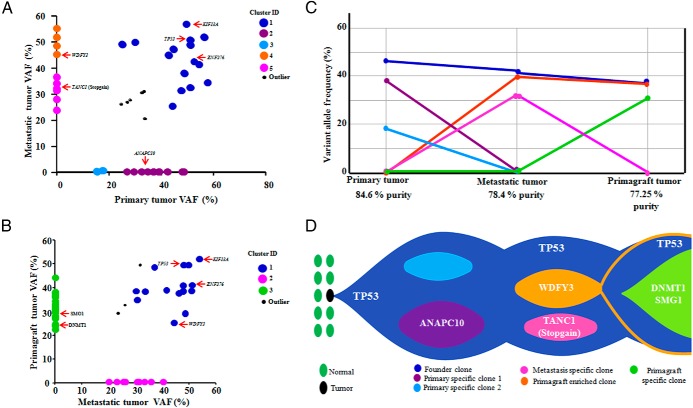

The variant allele frequencies (VAFs) for somatic mutations validated in each tumor sample were determined by using WES data (mean depth of 164 reads). Based on the VAF distribution, the number and size of the clonal populations in each tumor sample was calculated. Based on mutation clustering results, 3 clones were observed with a distinct set of mutations in the primary tumor. The median mutant allele frequencies in the primary tumors for cluster 1–3 were 42.3%, 39.13%, 18% (Figure 6, A and C). Cluster 1 is the “founder” since the other subclones were derived from it. We assume that almost all of these mutations are heterozygous with a variant allele frequency of 40–50% and must be present virtually in all the tumor cells of the primary and metastasis (Figure 6D). Clusters 2 and 3 mutations must be derived from clone 1. A single clone containing all of the cluster 4 mutations was detected in the metastatic sample. Clone 5 evolved from clone 4, but gained additional mutations. However, in the metastasis and primagraft, three mutant clones were noted. Clone 1 represents the “founder” which is present in both the metastatic (clone 2) and primagraft clones (clone 3) (Figure 6D). Clone 4 mutations were present both in the metastatic tumor and primagraft, but were absent in the primary tumor (Figure 6, B-D). Taken together, progression of the disease was accompanied by acquiring additional somatic mutations.

Figure 6.

Clonal evolution of the primary and metastatic ATC samples and the > 1 year continuous passaged ATC primagraft and graphical representation of clonal evolution from primary to metastatic to primagraft. A and B, Diagonal plots showed the distribution of variant allele frequencies (VAF) of validated mutations listed in Supplemental Table 9 in both primary and metastasis (A); and in both metastasis and primagraft (B), where VAFs of genes in the region of uniparental disomy (UPD) were halved. Driver mutations including TP53 are indicated by red arrows. In A, the founding clones in the primary and metastatic tumor are represented by blue, whereas pink and orange represent metastasis specific clones. Similarly in B, green represented the primagraft specific clone. C, Mutation clusters observed in the primary, metastatic, and primagraft tumors. Relationship between clusters in the primary, metastasis, and primagraft are indicated by linking the lines between them. D, The “founder” clone in the primary tumor contained somatic mutation in the TP53 gene. The dominant clones in the primary ATC tumor evolved into the metastatic clone by acquiring metastatic specific mutations. One of the clones in the metastasis (founder) also emerged as a founder clone in the primagraft. Another dominant clone at metastasis remained in the primagraft clone; also a primagraft specific clone emerged.

Discussion

ATC is a rare malignancy, but extremely aggressive and resistant to chemotherapy (26). Cell line model systems have made significant contributions to cancer research. Most cancer cell lines are from either primary or metastatic tumors. In this study, we have established, to our knowledge, the first matching human ATC cell lines from the primary (OGK-P) and the metastatic lymph node (OGK-M). In addition, a primagraft was established directly from the metastatic lymph-node which has been serially passaged for more than 1 year in NSG mice (OGK-primagraft). The primagraft has never been grown in vitro.

Our newly established cell lines formed aggressive tumors in athymic nude mice and robustly recruited blood vessel formation. In addition, mice carrying these cells developed splenomegaly containing increased myeloid cells, but no tumor cells. Furthermore, the xenografts were markedly infiltrated with neutrophils and macrophages suggesting the tumor cells were producing chemokines to stimulate the migration of hematopoietic cells to the tumors. Our microarray and qPCR data revealed that our established ATC lines had very high expression of various cytokines. Furthermore, condition media collected from these ATC cells stimulated clonogenic growth of murine hematopoietic committed stem cells to form granulocyte and macrophage colonies. Of note, we also performed IHC on the patient's thyroid tumor and lymph node metastasis and found rich invasion with neutrophils and macrophages (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B). Previously, Fagin's group (27) as well as others (28) have noted hematopoietic cell invasion into ATC. Recently, investigators working with many different model systems using a variety of tumors have posited that these invading hematopoietic cells enhance the growth of the tumors (29). Here, we showed that the primary and metastatic ATC cells produce many types of cytokines, which probably explains both the rich invasion of hematopoietic cells into the tumor, as well as the leukocytosis found in the patient.

qPCR and Western blot data showed high expression of VEGF-A in ATC patient samples, ATC cell lines (OGK-P, OGK-M, OGK-primagraft, SW1736, HTH7, T238, CAL62) compared to adjacent noncancerous tissue. Humanized monoclonal antibody, Bevacizumab, binds and inhibits VEGF-A, and is FDA approved for treatment of various cancers including colorectal, lung, renal tumors, as well as gliomas. Bevacizumab in combination with doxorubicin is in phase two clinical trial for ATCs patients. Treatment with Bevacizumab in mice carrying OGK-M xenografts significantly decreased their tumor growth and weight; and the mice tolerated the therapy with no apparent side effects (eg, weight loss).

High density SNP arrays noted that OGK-P, OGK-M, and OGK-primagraft cells had a small homozygous deletion at chromosome 10p11.21 encompassing exons 3–22 of the PARD3 gene. PARD3 is a master regulator of apical-basal cell polarity, a process that has been indirectly implicated in tumorigenesis (30, 31). OGK-P, OGK-M, OGK-primagraft, HTH7, C643, and T241 ATC cells had either undetectable or very low protein expression levels of PARD3. Furthermore, force-expression of PARD3 in OGK-M cells suppressed their cellular proliferation, motility, invasion, and enhanced the formation of cell-cell junctions, as well as cell adhesion to the collagen type1 and fibronectin. Taken together, PARD3 behaves as a tumor suppressor in thyroid cells, and ATC cells lose expression of the gene to enhance their invasive features.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology enhances scientific knowledge and aid in making clinical decisions. NGS can even be performed on formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded tissue (32). To our knowledge, this is the first report of WES of a primary and metastatic ATC, as well as comparing these results to the metastatic tumor passaged in NSG mice for > 1 year (primagraft). All mutations were validated by a second technique (Sanger sequencing). Burden of mutations was higher in the metastatic tumor and primagraft compared to the primary ATC tumor. Also, C > T and G > A transitions and A.T > C.G and C.G > G.C transversions were the most frequent mutations in these three tumor types, but their frequency varied between them. Using a variety of software (SIFT, PolyPhene), meaningful driver mutations were identified. A TP53 homozygous mutation was verified in the primary and metastatic tumors, as well as the primagraft passaged for > 1 year. TP53 mutations have been associated with primary ATC and ATC cell lines suggesting that inactivation of p53 confers aggressive properties to these neoplasms (33).

Cancer is a clonal disorder beginning in one cell which acquires a driver mutation. Driver mutations contribute to the tumor progression by giving cancer cells a growth advantage. As the tumor progresses, cancer cells also acquire additional mutations, known as passenger mutations providing no clonal growth advantage. Over time, individual cells will acquire additional driver mutations resulting in subclones of the original clone. Thus, most cancers have a founder clone and a series of subclones will be derived from it. At the same time, the subclones continue to amass passenger mutations. From deep sequencing, somatic variant frequencies help to determine both the founder clone, as well as the subclones. The founder clone should have the greatest number of copy number variants. Deep sequencing of our primagrafts, which had been grown in vivo for nearly 19 months, as well as the primary and metastatic tumor determined that the founder clone remained in the primagraft. However, in addition, a few additional mutations were acquired by the primagraft that likely enhanced its growth. In addition, we assumed that a number of passenger genes were acquired over this time period. In addition, because certain subclones perhaps ceased to exist in the primagraft, mutant genes in these subclones were no longer detectable as compared to the primary and metastatic thyroid cancer samples.

Recent studies noted the importance of clonal evolution in tumor progression and development of metastasis (34, 35). Our data displayed a wide range of mutant allele frequencies suggesting considerable genetic heterogeneity in the cellular population of the primary tumor. The range of mutational frequencies narrowed in the metastasis and primagraft, indicating that they evolved to a distinct subset of the mutational repertoire of the primary tumor.

Several commercial companies are advertising the therapeutic discriminatory power of growing primagrafts of the patient's tumors, sequencing the primagraft to identify targetable mutations followed by treating the tumor bearing mice with selective drugs. We found that primary and metastatic ATC samples contained 11 mutated genes not present in the primagraft. Furthermore, the primagraft after 20 passages over 19 months had 14 mutant genes not present in either the primary or metastatic lesions. We do not know if these primagraft specific mutations were also present at an “undetectable” frequency in the primary and metastatic tumors. At this stage, our data suggest some caution in the acceptance of a proposed therapy as suggested by primagraft analysis because the driver mutations may have developed in the primagraft independent of its development in the primary tumors. Nevertheless, our data showed that the “founder” clone was present in the primagraft thus testing for drugs directed against the “founder” mutant gene may provide a therapeutic benefit.

In summary, we developed a matched pair of primary and metastatic aggressive ATC cell lines that easily form xenografts recruiting copious blood vessels associated with high levels of VEGF. Treatment of these mice with Bevacizumab markedly decreased the growth of these tumors. The SNP array showed homozygous deletion of PARD3; re-expression of PARD3 inhibited ATC proliferation, motility and renewed the normal tiled epithelial pattern. Deep nucleotide sequencing of the primary, metastasis and primagrafts suggest that new somatic mutations do occur during the clinical course of the disease, but most of the original “founder” mutations present in the primary tumor were also present in the metastasis and primagraft, suggesting that early primagrafts are valid for functional and therapeutic studies. Nevertheless, our data provide a warning that mutational evolution occurs in these primagrafts, which may differ from the mutational landscape of the patient's primary tumor.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Singapore Ministry of Health's National Medical Research Council under its Singapore Translational Research (STaR) Investigator Award to H. Phillip Koeffler (National Research Foundation Singapore and the Singapore Ministry of Education under the Research Centres of Excellence initiative) and NIH Grant No. 2R01CA026038-35. Generous support also comes from the Thyroid Centre of Excellence, Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ANCT

- adjacent noncancerous tissue

- ATC

- anaplastic thyroid carcinoma

- PARD3

- par-3 partitioning defective 3 homolog (C. elegans)

- PAX8

- paired box gene 8

- SNP

- single nucleotide polymorphism

- TG

- thyroglobulin

- TTF1

- transcription factor 1

- VAFs

- variant allele frequencies

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFA

- vascular endothelial growth factor A

- WBC

- white blood cells

- WES

- whole exome sequencing

- ZO-1

- Zonula occludens 1.

References

- 1. Neff RL, Farrar WB, Kloos RT, Burman KD. Anaplastic thyroid cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37:525–538, xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Neill JP, Shaha AR. Anaplastic thyroid cancer. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeLellis RA, Williams ED. Tumors of the thyroid and parathyroid. In: DeLellis RA, Lloyd RV, Heitz PU, Eng C, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Endocrine Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004:49–93. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hebrant A, Dom G, Dewaele M, et al. mRNA expression in papillary and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: molecular anatomy of a killing switch. Plos One. 2012;7(10):e37807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ding L, Ellis MJ, Li S, et al. Genome remodelling in a basal-like breast cancer metastasis and xenograft. Nature. 2010;464:999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JJ, Foukakis T, Hashemi J, et al. Molecular cytogenetic profiles of novel and established human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma models. Thyroid. 2007;17:289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schweppe RE, Klopper JP, Korch C, et al. Deoxyribonucleic acid profiling analysis of 40 human thyroid cancer cell lines reveals cross-contamination resulting in cell line redundancy and misidentification. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4331–4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodrigues RF, Roque L, Krug T, Leite V. Poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid carcinomas: chromosomal and oligo-array profile of five new cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1237–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okamoto R, Ogawa S, Nowak D, et al. Genomic profiling of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia by single nucleotide polymorphism oligonucleotide microarray and comparison to pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95:1481–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamamoto G, Nannya Y, Kato M, et al. Highly sensitive method for genomewide detection of allelic composition in nonpaired, primary tumor specimens by use of affymetrix single-nucleotide-polymorphism genotyping microarrays. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:114–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of affymetrix genechip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chua SW, Vijayakumar P, Nissom P, Yam CY, Wong VV, Yang H. A novel normalization method for effective removal of systematic variation in microarray data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature. 2011;478:64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hayano T, Garg M, Yin D, et al. SOX7 is down-regulated in lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garg M, Kanojia D, Okamoto R, et al. Laminin-5γ-2 (LAMC2) is highly expressed in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma and is associated with tumor progression, migration, and invasion by modulating signaling of EGFR. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E62–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garg M, Kanojia D, Suri S, et al. Sperm-associated antigen 9: a novel diagnostic marker for thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4613–4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garg M, Kanojia D, Khosla A, et al. Sperm-Associated Antigen 9 is associated with tumor growth, migration, and invasion in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8240–8248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mansouri A, Chowdhury K, Gruss P. Follicular cells of the thyroid gland require Pax8 gene function. Nat Genet. 1998;19:87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bishop JA, Sharma R, Westra WH. PAX8 immunostaining of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a reliable means of discerning thyroid origin for undifferentiated tumors of the head and neck. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1873–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoang-Vu C, Dralle H, Scheumann G, et al. Gene expression of differentiation- and dedifferentiation markers in normal and malignant human thyroid tissues. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 1992;100:51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eskens FA, Sleijfer S. The use of bevacizumab in colorectal, lung, breast, renal and ovarian cancer: where does it fit? Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2350–2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Borgström P, Hillan KJ, Sriramarao P, et al. Complete inhibition of angiogenesis and growth of microtumors by anti-vascular endothelial growth factor neutralizing antibody: novel concepts of angiostatic therapy from intravital videomicroscopy. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4032–4039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rothenberg SM, Mohapatra G, Rivera MN, et al. A genome-wide screen for microdeletions reveals disruption of polarity complex genes in diverse human cancers. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2158–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475:101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smallridge RC, Ain KB, Asa SL, et al. American thyroid association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2012;22:1104–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ryder M, Glid M, Hohl TM, et al. Genetic and pharmacological targeting of CSF-1/CSF-1R inhibits tumor associated macrophages and impairs BRAF-induced thyroid cancer progression. Plos One. 2013;8:e54302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paolini R, Toffoli S, Poletti A, et al. Splenomegaly as the first manifestation of thyroid cancer metastases. Tumori. 1997;83:779–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bateman A. Growing a tumor stroma: a role for granulin and the bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:516–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bilder D, Li M, Perrimon N. Cooperative regulation of cell polarity and growth by Drosophila tumor suppressors. Science. 2000;289:113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pagliarini RA, Xu T. A genetic screen in Drosophila for metastatic behavior. Science. 2003;302:1227–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duncavage EJ, Magrini V, Becker N, et al. Hybrid capture and next-generation sequencing identify viral integration sites from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fagin JA, Matsuo K, Karmakar A, et al. High prevalence of mutations of the p53 gene in poorly differentiated human thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481:506–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]