Abstract

Objective

To review the latest information about tuberculosis (TB) drug resistance and programmatic management of drug-resistant TB in the Western Pacific Region of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Methods

We analysed routine data reported by countries to WHO from 2007 to 2013, focusing on data from the following: surveillance and surveys of drug resistance, management of drug-resistant TB and financing related to multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) management.

Results

In the Western Pacific Region, 4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3–6) of new and 22% (95% CI: 18–26) of previously treated TB cases were estimated to have MDR-TB; this means that in 2013, there were an estimated 71 000 (95% CI: 47 000–94 000) MDR-TB cases among notified pulmonary TB cases in this Region. The coverage of drug susceptibility testing (DST) among new and previously treated TB cases was 3% and 20%, respectively. In 2013, 11 153 cases were notified—16% of the estimated MDR-TB cases. Among the notified cases, 6926 or 62% were enrolled in treatment. Among all enrolled MDR-TB cases, 34% had second-line DST and of these, 13% were resistant to fluoroquinolones (FQ) and/or second-line injectable agents. The 2011 cohort of MDR-TB showed a 52% treatment success. Over the last five years, case notification and enrolment have increased more than five times, but the gap between notification and enrolment widened.

Discussion

The increasing trend in detection and enrolment of MDR-TB cases demonstrates readiness to scale up programmatic management of drug-resistant TB at the country level. However, considerable challenges remain.

Introduction

Globally an estimated 1.6 million people develop tuberculosis (TB), and 110 000 die from this curable illness annually.1 TB concentrates in vulnerable populations such as migrants, children, the elderly and the poor. The Western Pacific Region of the World Health Organization (WHO) has made substantial progress and reached the TB-related Millennium Development Goals and associated international targets in advance of the 2015 goal year: TB prevalence and mortality are below half of 1990 levels, and case detection and treatment success remain high.1 Despite these gains, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that is resistant to isoniazid and rifampicin (two of the first-line drugs used for treatment) poses a formidable challenge to controlling TB. MDR-TB cases can either be previously treated TB cases that develop resistance due to inadequate, incomplete or poor treatment quality (secondary drug resistance) or newly diagnosed TB cases infected with a drug-resistant TB strain (primary drug resistance). In 2013, among patients notified with pulmonary TB, a total of 300 000 (range: 230 000–380 000) people globally were estimated to have developed MDR-TB.1 Among them, approximately one quarter occurred in countries of the WHO Western Pacific Region. In fact, every year, an estimated 71 000 MDR-TB cases are added to the Region’s MDR-TB burden.1 Most (more than 94%) of the MDR-TB cases in the Region live in three countries: China, the Philippines and Viet Nam.

MDR-TB is a public health challenge for several reasons: treatment duration is very long, up to two years, and complex due to severe side-effects of second-line drugs2,3; high management costs may contribute to the increased economic burden and catastrophic patient expenditures4; treatment outcome is poor1; and MDR-TB poses a huge burden on health systems in low- and middle-income countries where human resources are scarce and technical capacity is lacking to cope with the challenge.5

To address the challenge of drug resistance in the WHO Western Pacific Region, the Regional strategy to stop tuberculosis in the Western Pacific 2011–20156 declared scaling up the programmatic management of drug-resistant TB (PMDT) as one of its five objectives. This requires improvements in the following critical steps of the cascade of services: (1) step-wise increase of the proportion of TB cases who receive drug susceptibility testing (DST), (2) all diagnosed patients are promptly notified and enrolled in treatment, and (3) all enrolled patients complete their treatment with effective patient-centred support. In 2011, the Western Pacific regional Green Light Committee was established to assist Member States with a rational PMDT scale-up.

This article is the second in a series of regional TB reports after ‘Epidemiology and control of tuberculosis in the Western Pacific Region: analysis of 2012 case notification data’.7 In this current article, we reviewed the latest available data on TB drug resistance in the WHO Western Pacific Region and the status of its programmatic implementation. This analysis of MDR-TB case detection, notification, enrolment into treatment and outcome of treatment data will provide valuable information on programmatic progress and future direction.

Methods

In this report, the data reported to WHO by countries and areas from 2007 to 2013 were used. In 2013, 32 of the 37 countries and areas of the WHO Western Pacific Region reported data to WHO, representing more than 99.9% of the total population. Data collection covers the following areas: TB case notification and treatment outcomes, diagnostic and treatment services, drug management, surveillance and surveys of drug-resistance, information on TB/HIV coinfection, infection control, engagement of all care providers and budgets and expenditures for TB control.

The estimated burden of drug-resistant TB by country was sourced from the global TB database, where the proportion of new and previously treated TB cases with MDR-TB from the latest available information from routine surveillance or a survey of drug resistance were used to estimate the total caseload of drug-resistant TB. The full description of these methods is available in the Global Tuberculosis Report 2014,1 and the data sets can be downloaded from the WHO global TB database (www.who.int/tb/data).

This report describes the available data on TB drug resistance and progress in programmatic response for those countries and areas of the Region where at least one MDR-TB case was notified in 2013. Trends of MDR-TB rates over time were assessed for countries and areas with more than one survey or surveillance data points since 1996. A special focus was maintained on seven countries considered priority countries due to their high burden of TB: Cambodia, China, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines and Viet Nam.

In 2013, WHO published revised TB case definitions and introduced a case definition for TB cases resistant to rifampicin only (RR-TB).8 A new rapid diagnostic technology, Xpert MTB/RIF assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), endorsed by WHO in 2010,9 tests for RR-TB. RR-TB cases identified by the Xpert MTB/RIF test are recommended to start second-line TB treatment10 and require similar management to MDR-TB cases. In this report, we included RR-TB cases with the confirmed MDR-TB cases.

Treatment outcomes are reported for the 2011 cohort, the most recent year for which there are data.

Analysis was conducted using the statistical package R (R Core Team, 2013, Vienna, Austria, www.R-project.org). For transparent and reproducible research,11,12 we have published the programme code for generating the entire contents of this article using the R knitr package.

Results

Coverage of drug resistance surveillance

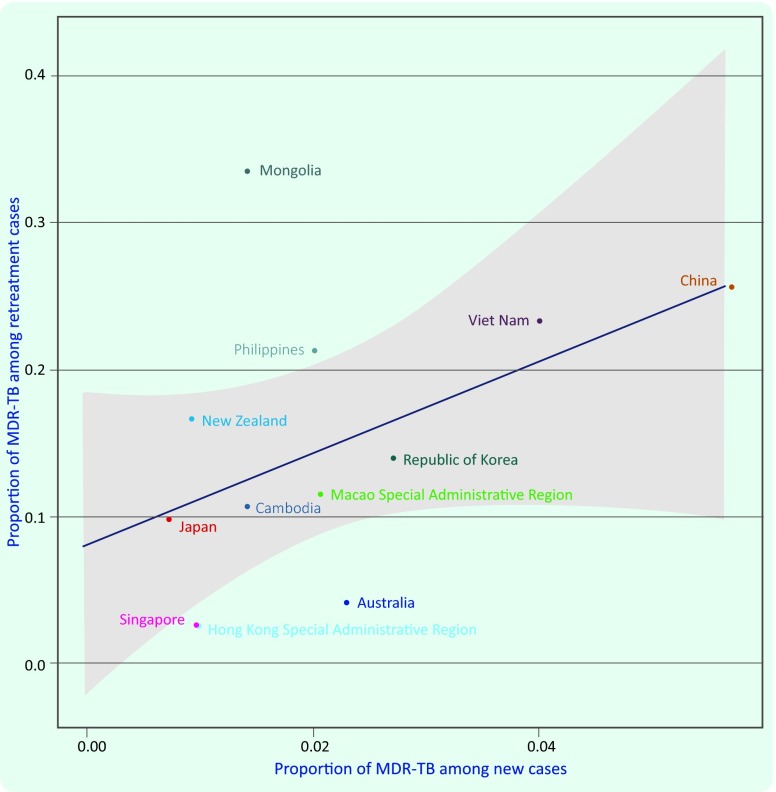

Estimates of the MDR-TB burden depend on the availability of drug resistance data from either continuous surveillance or surveys. Drug resistance data were available from 25 of the 36 countries and areas of the WHO Western Pacific Region (Fig. 1); 19 rely on routine surveillance and six rely on periodic surveys of representative samples of patients (Cambodia, China, Mongolia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Viet Nam).

Figure 1.

Year of most recent data on TB drug resistance by country, WHO Western Pacific Region, 1997–2014

National representative drug resistance survey (DRS) data are available from five out of seven priority countries of the Region (Cambodia, China, Mongolia, the Philippines and Viet Nam). Among them, Cambodia, Mongolia, the Philippines and Viet Nam have at least two national representative survey data points, and China is currently conducting its second national DRS. Malaysia’s 1997 data originated from geographical areas that were not considered representative of the country as a whole. Two countries with outstanding DRS data are Papua New Guinea and the Lao People's Democratic Republic. Subnational DRS in Papua New Guinea is ongoing and results are expected to be available in 2015.

Estimated MDR-TB burden: cases and rates

Overall in the Region in 2013, 4% (95% confidenc interval [CI]: 3–6) of new and 22% (95% CI: 18–26) of previously treated TB cases were estimated to have MDR-TB: 71 000 in total, 53 000 (75%) among new cases and 18 000 (25%) among previously treated TB cases (Table 1). The proportion of new TB cases with MDR-TB ranged from 0% to 6%. China had the highest proportion at 6% (95% CI: 5–7) of MDR-TB among new cases. The proportion of previously treated TB cases with MDR-TB ranged from 0% to 34%. Mongolia had the highest estimated proportion at 34% (95% CI: 29–38) of MDR-TB among previously treated TB cases. Countries with more than 20% MDR-TB among previously treated TB cases were China (26%), Mongolia (34%), the Philippines (21%) and Viet Nam (23%). Although the highest proportion of MDR-TB was observed among previously treated TB cases, the absolute number of estimated MDR-TB cases is higher among new cases.

Table 1. Estimated number and proportion of MDR-TB cases among new and previously treated TB cases by selected country,* WHO Western Pacific Region.

| Countries and areas | Data type | Year | MDR-TB among new cases | MDR-TB among previously treated TB cases | Total MDR-TB cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (95% CI) | % | N | (95% CI) | % | N | (95% CI) | |||||

| Australia | Surveillance | 2013 | 16 | (9–27) | 2 | (1–4) | 1 | (0–7) | 4 | (<1–21) | 17 | (8–26) |

| Brunei Darussalam | Surveillance | 2013 | 1 | (0–6) | <1 | (<1–4) | 0 | (0–3) | 0 | (0–46) | 1 | (0–3) |

| Cambodia | Survey | 2007 | 320 | (160–580) | 1 | (<1–3) | 180 | (68–370) | 11 | (4–22) | 510 | (270–740) |

| China | Survey | 2007 | 45 000 | (35 000–55 000) | 6 | (5–7) | 9200 | (7800–11 000) | 26 | (22–30) | 54 000 | (48 000–61 000) |

| Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | Surveillance | 2012 | 34 | (21–52) | <1 | (<1–1) | 9 | (3–20) | 3 | (<1–6) | 43 | (26–59) |

| Macao Special Administrative Region | Surveillance | 2013 | 7 | (2–16) | 2 | (<1–5) | 4 | (1–10) | 12 | (2–30) | 11 | (4–18) |

| Cook Islands | Surveillance | 2013 | 0 | (0–1) | 0 | (0–98) | 0 | (0–0) | 0 | (0–0) | 0 | (0–1) |

| Japan | Surveillance | 2002 | 110 | (63–160) | <1 | (<1–1) | 100 | (72–130) | 10 | (7–13) | 200 | (150–260) |

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | Model† | 160 | (96–230) | 5 | (3–6) | 65 | (56–75) | 24 | (20–27) | 220 | (160–290) | |

| Malaysia | Survey | 1997 | 19 | (0–120) | <1 | (0–<1) | 0 | (0–340) | 0 | (0–17) | 19 | (0–57) |

| Marshall Islands | Surveillance | 2013 | 2 | (0–9) | 1 | (<1–7) | 0 | (0–5) | 0 | (0–71) | 2 | (0–5) |

| New: Survey | 2007 | |||||||||||

| Mongolia | Previously treated TB: Surveillance | 2013 | 33 | (16–59) | 1 | (<1–3) | 210 | (180–240) | 34 | (29–38) | 240 | (210–280) |

| New Zealand | Surveillance | 2012 | 1 | (0–5) | <1 | (<1–3) | 2 | (0–5) | 17 | (2–48) | 3 | (0–6) |

| Palau | Surveillance | 2013 | 0 | (0–3) | 0 | (0–41) | 0 | (0–0) | 0 | (0–0) | 0 | (0–3) |

| Papua New Guinea | Model† | 560 | (340–800) | 5 | (3–6) | 570 | (480–650) | 24 | (20–27) | 1100 | (890–1400) | |

| Philippines | Survey | 2013 | 4400 | (3100–6000) | 2 | (1–3) | 4100 | (3000–5500) | 21 | (16–29) | 8500 | (6900–10 000) |

| Republic of Korea | Surveillance | 2004 | 780 | (600–980) | 3 | (2–3) | 1200 | (850–1600) | 14 | (10–19) | 1900 | (1600–2300) |

| Singapore | Surveillance | 2013 | 17 | (8–30) | <1 | (<1–2) | 3 | (0–12) | 3 | (<1–9) | 20 | (9–31) |

| Viet Nam | Survey | 2012 | 3000 | (1900–4100) | 4 | (3–5) | 2100 | (1500–2600) | 23 | (17–30) | 5100 | (4100–6100) |

| Western Pacific Region | 53 000 | (31 000–75 000) | 4 | (3–6) | 18 000 | (15 000–21 000) | 22 | (18–26) | 71 000 | (47 000–94 000) | ||

Source: Global TB database.

CI, confidence interval; MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

* Countries that reported at least one MDR-TB case in 2013.

† Estimates of the proportion of new and previously treated TB cases that have MDR-TB were produced using modelling (including multiple imputation) that was based on data from countries that were considered to be similar in terms of TB epidemiology for which data do exist.

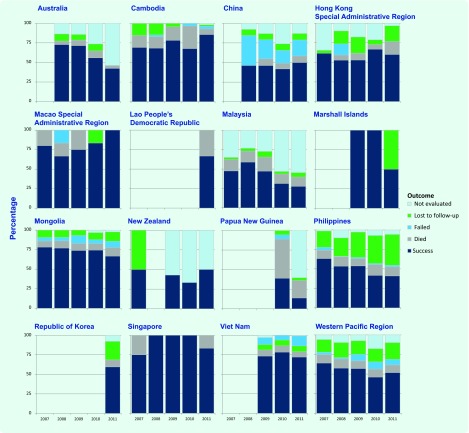

There was a positive correlation between the proportion of MDR-TB among new and previously treated TB cases (intercept 0.08%, coefficient 3.1%, F-statistics 3.84, P = 0.123; Fig. 2), although this was not statistically significant. Most countries and areas fell within 95% confidence limits of the linear regression line except for Mongolia and the Philippines. Both had a higher proportion of MDR-TB among previously treated TB cases in relation to new cases. Australia, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and Singapore, had a lower proportion of MDR-TB among previously treated TB cases relative to new cases.

Figure 2.

Correlation* between the estimated proportion of MDR-TB cases among new and previously treated TB cases respectively by selected country,† WHO Western Pacific Region, 2013

MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

* Line represents the linear regression and the grey band represents 95% CI.

† Countries that reported their own MDR-TB estimates for new and previously treated cases in 2013.

Estimated MDR-TB burden over time

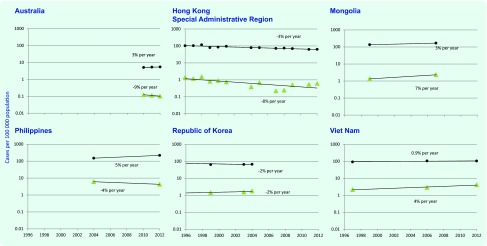

Among 25 countries with drug resistance data, 22 countries have more than one data point (direct measurement) either from continuous surveillance or from repeat surveys. Four scenarios are observed when comparing rates per 100 000 population of new TB cases with the estimated rate of MDR-TB among new TB cases from six countries in the Western Pacific Region (Fig. 3). For Mongolia and Viet Nam, both the reported notification rate of new TB cases and estimated rate of MDR-TB increased over time (7% and 4% per year from 1999 to 2007 and 1997 to 2012, respectively). In Australia and the Philippines, TB notification rates increased while the rate of MDR-TB decreased (–4% and –10% per year from 2004 to 2012 and 2010 to 2012, respectively). In Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, both the TB notification rate and estimated rate of MDR-TB decreased (–8% for both from 1996 to 2012). In the Republic of Korea, TB case notification decreased, but the estimated rate of MDR-TB increased by 2% from 1996 to 2005. These findings need to be interpreted with caution as sufficient data points are not available for all of the countries to identify trends with confidence.

Figure 3.

Rates per 100 000 population of new TB cases (black) and estimated MDR-TB cases among new TB cases (green) by selected countries, WHO Western Pacific Region, 1996–2012

MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

Drug susceptibility testing (DST)

DST data were reported from 18 countries in 2013. Only 3% of new bacteriologically confirmed TB cases and 20% of previously treated TB cases were tested for MDR-TB or RR-TB (Table 2). DST coverage for MDR-TB among new cases was less than 10% in China (3%), the Lao People's Democratic Republic (< 1%), the Philippines (< 1%), the Republic of Korea (4%) and Viet Nam (3%) and among previously treated TB cases. DST coverage remained below 50% in China (20%), Japan (43%), the Lao People's Democratic Republic (26%), Malaysia (9%), the Marshall Islands (43%), the Philippines (14%), the Republic of Korea (9%) and Viet Nam (45%).

Table 2. Number and proportion of notified TB cases with DST results, confirmed MDR-TB and RR-TB cases and cases confirmed by Xpert, by new and previously treated TB cases and selected country,* WHO Western Pacific Region, 2013.

| Countries and areas | Notified cases with DST results | MDR-TB and RR-TB* among cases with DST results |

Cases confirmed by Xpert among MDR-TB and RR-TB† | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New | Prev | Total | New | Prev | Total | New | Prev | Total | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Australia | 570 | 82 | 25 | 76 | 604 | 83 | 13 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 17 | 3 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Brunei Darussalam | 146 | 92 | 6 | 100 | 152 | 93 | 1 | <1 | 0 | – | 1 | <1 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Cambodia | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| China | 20 080 | 3 | 7153 | 20 | 27 233 | 3 | 1612 | 8 | 2571 | 36 | 4183 | 15 | 244 | 15 | 246 | 10 | 490 | 12 |

| Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | 1919 | 55 | 198 | 56 | 2117 | 55 | 28 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 35 | 2 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Macao Special Administrative Region | 244 | 70 | 26 | 81 | 305 | 80 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Cook Islands | 1 | 100 | 0 | – | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Japan | 7266 | 49 | 435 | 43 | 7 | 42 | <1 | 22 | 5 | 64 | <1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 11 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | |||||

| Malaysia | 2702 | 14 | 181 | 9 | 11 110 | 52 | 80 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 185 | 2 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Marshall Islands | 72 | 61 | 3 | 43 | 75 | 60 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Mongolia | 289 | 12 | 531 | 85 | 838 | 28 | 24 | 22 | 177 | 33 | 242 | 29 | 15 | 23 | 38 | 21 | 53 | 22 |

| New Zealand | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Palau | 7 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | |||||

| Papua New Guinea | – | – | – | – | 93 | <1 | – | – | – | – | 46 | 49 | – | – | – | – | 33 | 72 |

| Philippines | 25 | <1 | 2631 | 14 | 2656 | 1 | 10 | 40 | 1349 | 51 | 1359 | 51 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Republic of Korea | 1249 | 4 | 726 | 9 | 1975 | 5 | 466 | 37 | 518 | 71 | 984 | 50 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Singapore | 1070 | 61 | 85 | 66 | 1155 | 62 | 14 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 18 | 2 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Viet Nam | 353 | <1 | 3955 | 45 | 4531 | 5 | 40 | 11 | 997 | 25 | 1041 | 23 | 37 | 92 | 801 | 80 | 841 | 81 |

| Western Pacific Region | 36 103 | 3 | 16 057 | 20 | 60 765 | 5 | 2379 | 7 | 5664 | 35 | 8195 | 13 | 296 | 12 | 1085 | 19 | 1417 | 17 |

DST, drug susceptibility testing; MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; Prev, previously treated tuberculosis; RR-TB, rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis.

* Countries that reported at least one MDR-TB case in 2013.

† Rifampicin-resistant only cases are included whether confirmed by DST or Xpert.

Among cases tested in 2013, 8% were resistant to isoniazid only, 2% were resistant to rifampicin only and 11% were resistant to both (data not shown). The Xpert MTB/RIF test identified 17% of MDR-TB cases overall and was highest for Viet Nam at 81% and Papua New Guinea at 72% (Table 2).

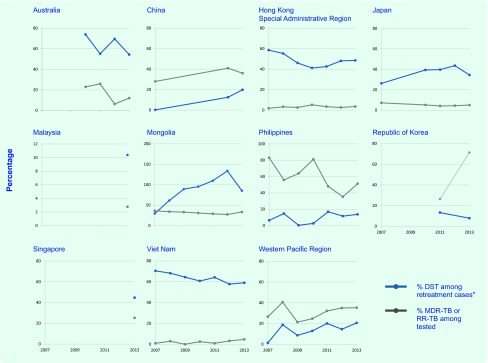

In countries with a high burden of MDR-TB, the DST coverage among previously treated TB cases increased steadily while the MDR-TB positivity rate remained high (Fig. 4). In fact, there is a general paradoxical tendency for countries with a relatively higher DST coverage to detect a lower proportion of MDR-TB.

Figure 4.

DST coverage among previously treated TB cases and MDR-TB and RR-TB positivity rate by year and selected countries, WHO Western Pacific Region, 2007–2013

DST, drug susceptibility testing; MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; RR-TB, rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis.

MDR-TB notifications and enrolment in treatment

There were 11 153 reported cases of MDR-TB and RR-TB in the Region in 2013, representing 16% of the 71 000 estimated MDR-TB cases among pulmonary TB patients. Of these, 2379 were reported among new TB cases, representing 4% of the estimated 53 000 MDR-TB cases among TB new cases; 5664 were reported among previously treated TB cases, representing 31% of the estimated 18 000 MDR-TB among previously treated TB cases. Mongolia, the Philippines and Viet Nam reported 84%, 33% and 47%, respectively, of their estimated MDR-TB among previously treated TB cases (Table 3).

Table 3. Number of estimated and notified MDR-TB and RR-TB cases, proportion notified among estimated MDR-TB and RR-TB cases and number and proportion of MDR-TB and RR-TB cases enrolled in treatment by selected country,* WHO Western Pacific Region, 2013†.

| Countries and areas | Estimated | Notified | Percentage notified among estimated | Enrolled in treatment | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New | Prev | Total | New | Prev | Total‡ | New | Prev | Total | |||||||||

| N | (95% CI) | N | (95% CI) | N | (95% CI) | N | (95% CI) | N | (95% CI) | N | (95% CI) | n | % among detected | ||||

| Australia | 16 | (8–27) | 1 | (0–7) | 17 | (8–26) | 13 | 3 | 24 | 81 | (48–144) | 300 | (43–NA) | 141 | (92–300) | 22 | 92 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 1 | (0–6) | 0 | (0–3) | 1 | (0–3) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 100 | (17–NA) | – | (0–NA) | 100 | (33–NA) | 0 | 0 |

| Cambodia | 320 | (270–580) | 180 | (68–370) | 510 | (270–740) | – | – | 121 | – | (NA–NA) | – | (NA–NA) | 24 | (16–45) | 121 | 100 |

| China | 45 000 | (48 000–55 000) | 9200 | (7800–11 000) | 54 000 | (48 000–61 000) | 1612 | 2571 | 4183 | 4 | (3–5) | 28 | (23–33) | 8 | (7–9) | 2184 | 52 |

| Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | 34 | (26–52) | 9 | (3–20) | 43 | (26–59) | 28 | 7 | 35 | 82 | (54–133) | 78 | (35–233) | 81 | (59–135) | 22 | 63 |

| Macao Special Administrative Region | 7 | (4–16) | 4 | (1–10) | 11 | (4–18) | 6 | 3 | 10 | 86 | (38–300) | 75 | (30–300) | 91 | (56–250) | 8 | 80 |

| Cook Islands | 0 | (0–1) | 0 | (0–0) | 0 | (0–1) | 0 | 0 | 2 | – | (0–NA) | – | (NA–NA) | NA | (200–NA) | 0 | 0 |

| Japan | 110 | (150–160) | 100 | (72–130) | 200 | (150–560) | 42 | 22 | 64 | 38 | (26–67) | 22 | (17–31) | 32 | (25–43) | – | – |

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 160 | (160–230) | 65 | (56–75) | 220 | (160–290) | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | (0–0) | 11 | (9–12) | 3 | (2–4) | 4 | 57 |

| Malaysia | 19 | (0–120) | 0 | (0–340) | 19 | (0–57) | 80 | 5 | 277 | 421 | (67–NA) | NA | (1–NA) | 1458 | (486–NA) | 49 | 18 |

| Marshall Islands | 2 | (0–9) | 0 | (0–5) | 2 | (0–5) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 50 | (11–NA) | – | (0–NA) | 50 | (20–NA) | 1 | 100 |

| Mongolia | 33 | (210–59) | 210 | (180–240) | 240 | (210–280) | 64 | 177 | 257 | 194 | (108–400) | 84 | (74–98) | 107 | (92–122) | 192 | 75 |

| New Zealand | 1 | (0–5) | 2 | (0–5) | 3 | (0–6) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 100 | (20–NA) | 50 | (20–NA) | 100 | (50–NA) | 2 | 67 |

| Palau | 0 | (0–3) | 0 | (0–0) | 0 | (0–3) | 0 | 0 | 1 | – | (0–NA) | – | (NA–NA) | NA | (33–NA) | 0 | 0 |

| Papua New Guinea | 560 | (890–800) | 570 | (480–650) | 1100 | (890–1400) | – | – | 119 | – | (NA–NA) | – | (NA–NA) | 11 | (8–13) | 145 | 122 |

| Philippines | 4400 | (6900–6000) | 4100 | (3000–5500) | 8500 | (6900–10 000) | 10 | 1349 | 3962 | <1 | (<1–<1) | 33 | (25–45) | 47 | (40–57) | 2262 | 57 |

| Republic of Korea | 780 | (1600–980) | 1200 | (850–1600) | 1900 | (1600–2300) | 466 | 518 | 984 | 60 | (48–78) | 43 | (32–61) | 52 | (43–62) | 951 | 97 |

| Singapore | 17 | (9–30) | 3 | (0–12) | 20 | (9–31) | 14 | 4 | 18 | 82 | (47–175) | 133 | (33–NA) | 90 | (58–200) | 15 | 83 |

| Viet Nam | 3000 | (4100–4100) | 2100 | (1500–2600) | 5100 | (4100–6100) | 40 | 997 | 1204 | 1 | (<1–2) | 47 | (38–66) | 24 | (20–29) | 948 | 79 |

| Western Pacific Region | 53 000 | (47 000–75 000) | 18 000 | (15 000–21 000) | 71 000 | (47 000–94 000) | 2379 | 5664 | 11 153 | 4 | (3–8) | 31 | (27–38) | 16 | (12–24) | 6926 | 62 |

CI, confidence interval; MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; NA, not applicable; Prev, previously treated tuberculosis; RR-TB, rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis.

* Countries that reported at least one MDR-TB case in 2013.

† All columns except estimates include RR-TB cases confirmed by Xpert only. Total MDR-TB cases detected included cases among extrapulmonary and from samples taken more than 2 weeks after start of treatment.

‡ Total column includes cases with treatment history unavailable.

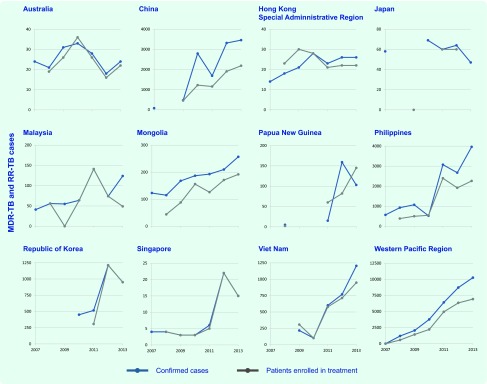

Of those notified MDR-TB cases in 2013, only 62% (6926 of 11 153) were enrolled in treatment with second-line anti-TB drugs. For most countries, there has been a steady increase in enrolment in treatment over the years, especially since 2011; however, the gap between notified cases and enrolment in treatment for MDR-TB is widening in China, the Philippines and Viet Nam (Table 4, Fig. 5).

Table 4. Number and proportion of MDR-TB and RR-TB cases resistant to second-line anti-TB drugs and XDR-TB, by selected country,* WHO Western Pacific Region, 2013.

| Countries and areas | Second-line DST | Resistance to FQ | Resistance to second-line injectible | XDR-TB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % of enrolled | N | % of tested | N | % of tested | N | % of tested | |

| Australia | 12 | 55 | 2 | 17 | 1 | 8 | 0 | – |

| Brunei Darussalam | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cambodia | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| China | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | 26 | 118 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 4 |

| Macao Special Administrative Region | 7 | 88 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Cook Islands | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Japan | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 4 | 100 | 1 | 25 | 0 | _ | 0 | – |

| Malaysia | 113 | 231 | 12 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 1 | <1 |

| Marshall Islands | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mongolia | 113 | 59 | 6 | 5 | 15 | 13 | 5 | 4 |

| New Zealand | 2 | 100 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Palau | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Papua New Guinea | 73 | 50 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | – | – |

| Philippines | 927 | 41 | 59 | 6 | 38 | 4 | 5 | <1 |

| Republic of Korea | 838 | 88 | 158 | 19 | 112 | 13 | 85 | 10 |

| Singapore | 12 | 80 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Viet Nam | 199 | 21 | 29 | 15 | 23 | 12 | 10 | 5 |

| Western Pacific Region | 2326 | 34 | 270 | 12 | 156 | 8 | 107 | 5 |

DST, drug susceptibility testing; FQ, fluoroquinolones; MDR-TR, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; RR-TB, rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis; XDR-TB, extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

* Countries that reported at least one MDR-TB case in 2013.

Figure 5.

Number of MDR-TB and RR-TB cases notified and enrolled in treatment by year and selected country,* WHO Western Pacific Region, 2007–2013

MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; RR-TB, rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis.

* Countries that reported at least 10 MDR-TB cases in 2013.

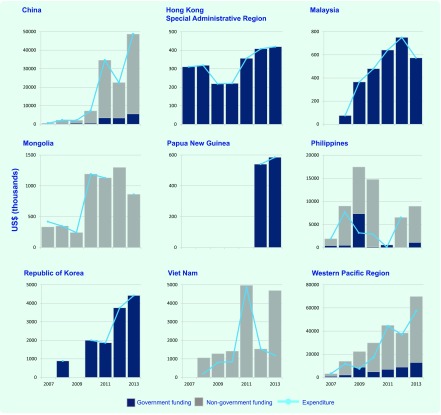

MDR-TB treatment outcomes

Treatment for the 2011 cohort were reported from 15 countries. Overall the proportion of MDR-TB cases who successfully completed treatment was 52%, with 21% lost to follow-up and 10% having died (Fig. 6). Treatment success was 100% in Macao Special Administrative Region yet only 14% in Papua New Guinea.

Figure 6.

Treatment outcomes of MDR-TB and RR-TB cases by year and selected country,* WHO Western Pacific Region, 2007–2011

MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; RR-TB, rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis.

* Countries that reported at least one MDR-TB case in 2013 and reported treatment outcomes for 2011.

In China, the treatment success rate was less than 50% between 2007 and 2011 with death and failure rates remaining high. Malaysia, and the Philippines showed a continuous decline of treatment success over the same time period; non-evaluation of cases is the main reason for Malaysia while loss to follow-up plays a major role in the decreasing success rate in the Philippines. Among the priority countries, Cambodia (86%) and Viet Nam (72%) had high treatment success for the 2011 cohort.

Second-line anti-TB DST and XDR-TB

Twelve countries reported testing data for the second-line anti-TB drugs in 2013, with 34% of enrolled MDR-TB cases having results for DST for the second-line anti-TB drugs. Combining data from all 12 countries, 12% of tested cases had resistance to fluoroquinolones (FQ), 8% to a second-line injectable and 13% to either a FQ or a second-line injectable agent or both. Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) is a subset of MDR-TB that acquired additional resistance to FQ and one or more of the second-line injectable agents. In 2013, the total number of reported XDR-TB cases was 107 (5% of tested MDR-TB cases) from six countries in the Region (17% of all countries and areas). The highest rate was reported from the Republic of Korea where 10% of all MDR-TB cases were XDR-TB.

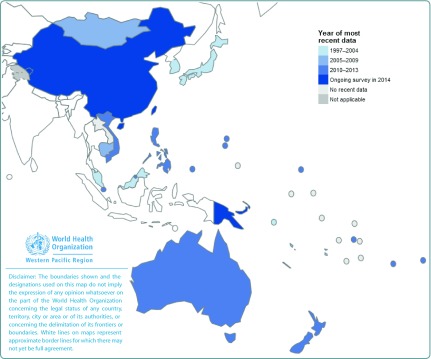

Expenditure for MDR-TB management

Expenditure for MDR-TB management has significantly increased over the years (Fig. 7). In 2013, a total of US $57.3 million was spent for MDR-TB management in the Region; this was 10.9% of the total national TB programme expenditure. Of the total funds reported, 18.4% was from domestic sources (government allocation) with the remaining 81.6% from external grants. Second-line drugs comprised 27.8% of the total cost for MDR-TB management.

Figure 7.

Expenditure on MDR-TB and RR-TB by funding source, year and selected country*, WHO Western Pacific Region, 2007–2013

MDR-TB, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; RR-TB, rifampicin-resistance tuberculosis.

* Countries that reported at least 10 MDR-TB cases in 2013.

Discussion

The Western Pacific Region comprises countries with high MDR-TB caseloads, such as China, the Philippines, Viet Nam, and several Pacific island nations with very small, irregular caseloads. The Member States are also at different stages of PMDT implementation.

The first step for PMDT scale-up is to establish diagnostic capacity and increase the proportion of TB cases who receive DST. The Global Plan to Stop TB13 set a target for DST at 100% of previously treated TB cases and 20% of new cases by 2015. Overall DST coverage remained low with the current coverage for new cases at 3% and previously treated TB cases at 20%, both far below the Global Plan to Stop TB target. The introduction of a rapid diagnostic tool has enabled a drastic increase in diagnostic capacity, as evidenced in Viet Nam, where 81% of notified MDR-TB cases were diagnosed by Xpert MTB/RIF in 2013. This analysis indicates that the expansion of DST coverage is still ongoing to cover the highest risk groups. Most countries starting PMDT focus on previously treated TB cases first, as diagnosing MDR-TB cases among new TB cases is a huge challenge in this Region. Although the proportion of MDR-TB among new TB cases is low, the absolute numbers are very high. It is a challenge to identify effective and efficient strategies to identify MDR-TB cases among new TB cases considering current financial and human resource capacity. To identify potential high-risk groups that can be targeted for selective DST, surveillance systems need to be expanded and strengthened.

XDR-TB is also a growing concern. Currently, second-line DST coverage is low at 34% as reported from 12 countries, and the true magnitude of XDR-TB burden is unknown. As PMDT is expanded with increased second-line DST capacity, more XDR-TB patients will likely be diagnosed. Programmes need to get ready to address XDR-TB with guidelines for the management of XDR-TB patients including policies for appropriate palliative care and infection control.

It is also of paramount importance that all TB cases diagnosed with MDR-TB are quickly put on treatment. Detection of MDR-TB cases is challenging and requires a lot of effort; if notified cases are not put on treatment, all these efforts will be in vain. It is alarming that overall in the Region in 2013, 38% of the notified cases were not put on treatment (48% in China, 43% in the Philippines and 21% in Viet Nam). As reported to the WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, reasons for this may be many-fold: some patients may be on the waiting list because of unavailability of treatment capacity including drugs, hospitalization and treatment support. Rapid scale-up of diagnostic capacity especially with Xpert MTB/RIF may not be accompanied by an increased treatment capacity. Another reason may be loss to follow-up of confirmed cases that can occur due to non-accessibility of PMDT centres; non-coordination between diagnostic and treatment sites; and economic burden to patients, including direct and indirect cost. Instead, these patients return to their community and continue to spread their MDR-TB strain. Increasing diagnostic capacity must be aligned with drug and treatment provision, and political commitment to coordinated treatment capacity to match diagnostic capacity is essential. In addition, underlying causes for the initial high loss to follow-up need to be identified and addressed. The call for integrated patient-centred TB care and prevention, and the bold policies and supportive systems in the WHO End TB strategy,14 need to be operationalized to address these issues. National TB programmes alone may not be able to address this misalignment between diagnostic capacity and treatment availability.

It is also imperative that all enrolled MDR-TB patients complete their treatment. As shown, treatment success rates in the Region are low at 52% for the 2011 cohort. This is similar to the global average of 48%.1 High proportions of MDR-TB cases lost to follow-up or not evaluated (21% and 17%, respectively) are part of this low success rates and result in continual transmission of drug-resistant TB strains. These low success rates challenge the usefulness of PMDT; however, Cambodia and Viet Nam showed treatment success rates above 70% over several years, showing that increasing treatment success for MDR-TB is possible.

The overall increase in notification and enrolment in treatment of MDR-TB cases demonstrates the readiness for PMDT scale-up at the country level. The results of this analysis showed that notification of TB cases is increasing; however, currently only 16% of the estimated MDR-TB among notified cases were reported under PMDT. Considerable challenges remain for scaling up PMDT with serious concerns regarding national political commitment and the long-term sustainability of donor-funded programmes that provide more than 80% of funding for MDR-TB.

The reader should note that the data reported in this analysis were not complete for all countries. As such, interpretation of the data should be made with caution.

MDR-TB is a man-made phenomenon, and unless the underlying cause is addressed, control efforts will not be successful. Prevention of MDR-TB including strengthening basic TB control needs to be at the centre of the strategy to address MDR-TB. Scaling-up of PMDT has to progressively improve all critical steps of the cascade of services in a balanced manner. TB control has entered the most dynamic phase in decades with many opportunities. We have new diagnostic tools, new TB drugs and new strategies. It is therefore critical to invest both financial and technical resources to prevent MDR-TB and to scale up PMDT.

Acknowledgement

The authors are very grateful to Matteo Zignol and Anna Dean for their comments on the draft publication. They also thank the national tuberculosis control programmes of the countries of the Western Pacific Region.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Global Tuberculosis Report 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr14_main_text.pdf accessed 5 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Companion handbook to the WHO guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/130918/1/9789241548809_eng.pdf?ua=1 accessed 5 December 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathanson E, et al. Adverse events in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: results from the DOTS-Plus initiative. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2004;8:1382–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wingfield T, et al. Defining catastrophic costs and comparing their importance for adverse tuberculosis outcome with multi-drug resistance: a prospective cohort study, Peru. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11:e1001675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abubakar I, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: time for visionary political leadership. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2013;13:529–39. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regional Strategy to Stop Tuberculosis in the Western Pacific 2011–2015. Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2011. http://www.wpro. who.int/tb/documents/policy/2010/regional_strategy/en/ accessed 5 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiatt T, Nishikiori N. Epidemiology and control of tuberculosis in the Western Pacific Region: analysis of 2012 case notification data. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal. 2014;5:25–34. doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2014.5.1.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis – 2013 revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/79199/1/9789241505345_eng.pdf accessed 5 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Automated real time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB in adults and children, policy update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112472/1/9789241506335_eng.pdf accessed 5 December 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xpert MTB/RIF implementation manual: technical and operational ‘how-to’: practical considerations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112469/1/9789241506700_eng.pdf accessed 5 December 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng RD, Dominici F, Zeger SL. Reproducible epidemiologic research. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163:783–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groves T, Godlee F. Open science and reproducible research. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2012;344:e4383. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Global Plan to Stop TB 2011–2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/global/plan/TB_GlobalPlanToStopTB2011-2015.pdf accessed 5 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHA 67.1. Global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R1-en.pdf accessed 5 December 2014. [Google Scholar]