Background: Subunits D and F are essential in ATP hydrolysis and reversible disassembly of V1VO-ATPases.

Results: First crystallographic structure of eukaryotic V-ATPase subunit D and entire subunit F is presented.

Conclusion: Structural elements in subunits D and F enable the DF assembly to become a central motor element in the engine V-ATPase.

Significance: Mechanistic understanding of the subunit DF assembly and its key roles in enzyme catalysis and regulation are presented.

Keywords: ATP Synthase, Bioenergetics, Proton Pump, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Vacuolar ATPase

Abstract

Eukaryotic V1VO-ATPases hydrolyze ATP in the V1 domain coupled to ion pumping in VO. A unique mode of regulation of V-ATPases is the reversible disassembly of V1 and VO, which reduces ATPase activity and causes silencing of ion conduction. The subunits D and F are proposed to be key in these enzymatic processes. Here, we describe the structures of two conformations of the subunit DF assembly of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ScDF) V-ATPase at 3.1 Å resolution. Subunit D (ScD) consists of a long pair of α-helices connected by a short helix (79IGYQVQE85) as well as a β-hairpin region, which is flanked by two flexible loops. The long pair of helices is composed of the N-terminal α-helix and the C-terminal helix, showing structural alterations in the two ScDF structures. The entire subunit F (ScF) consists of an N-terminal domain of four β-strands (β1–β4) connected by four α-helices (α1–α4). α1 and β2 are connected via the loop 26GQITPETQEK35, which is unique in eukaryotic V-ATPases. Adjacent to the N-terminal domain is a flexible loop, followed by a C-terminal α-helix (α5). A perpendicular and extended conformation of helix α5 was observed in the two crystal structures and in solution x-ray scattering experiments, respectively. Fitted into the nucleotide-bound A3B3 structure of the related A-ATP synthase from Enterococcus hirae, the arrangements of the ScDF molecules reflect their central function in ATPase-coupled ion conduction. Furthermore, the flexibility of the terminal helices of both subunits as well as the loop 26GQITPETQEK35 provides information about the regulatory step of reversible V1VO disassembly.

Introduction

Eukaryotic V-ATPases (V1VO-ATPases)4 are ATP-driven ion pumps, which generate an electrochemical proton gradient or proton-motive force across the membranes, leading to acidification of intracellular compartments (1, 2). Intracellular compartments of eukaryotic cells require the maintenance of acidic luminal pH by V-ATPase. The enzyme is also targeted to the plasma membrane and is involved in extracellular acidification of some specialized cells in the kidney, epididymis, and bone tissues (3). The V-ATPase acidifies the extra-tumoral environment in cancer (4). The pH becomes more acidic as the exocytic and endocytic vesicular trafficking pathways reach their destination (5). The regulation of V-ATPase function and V-ATPase-driven differential acidification is described to be achieved by the following: (a) modulation of V-ATPase dependent acidification via a chemiosmotic mechanism; (b) regulation of coupling of the V-ATPase; (c) subunit-specific targeting of V-ATPase; and (d) regulation of V-ATPase activity via reversible dissociation of the V1 and VO parts of the protein (5).

Eukaryotic V-ATPases consist of 14 different subunits A3B3CDE3FG3Hacxcy′cz″d, e, where the stoichiometry (x,y,z) of the c, c′, and c′ subunits are not known (6). Many of these subunits are present in multiple isoforms (3, 7). V1VO-ATPases have a bipartite structure consisting of a soluble cytoplasmic V1 domain (subunits A3B3CDE3FG3H) and a membrane-integrated VO domain (subunits a, c, c′, c″, d, e). Electron microscopy image analysis (8–11) and small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) (12, 13) have provided a general outline for the structural organization of the V1 and VO parts as well as the entire enzyme (Fig. 1). Both parts are linked by connecting regions that are important for coupling ion translocation in VO with ATP hydrolysis in V1 and are proposed to be involved in regulating the activity of the enzyme by reversible disassembly. These connecting regions consist of the central stalk subunits (D, F, and d) and peripheral stalk subunits (E, G, C, H, e, and a).

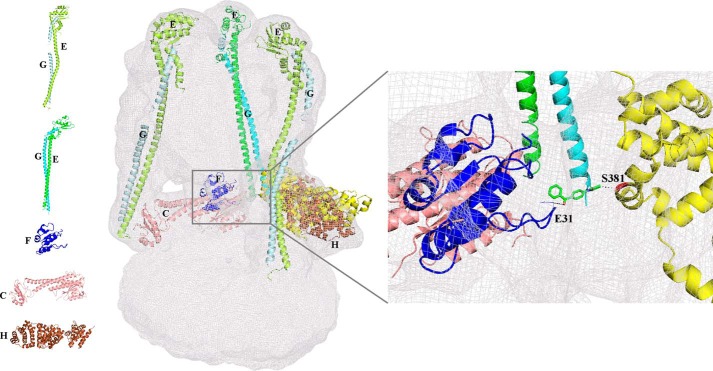

FIGURE 1.

Arrangement of the existing individual atomic subunit structures in the EM map of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase. Subunits C (1U7L; salmon), H (1HO8, brown), and F(1–94) (4IX9, blue) from S. cerevisiae were fitted into the EM map. The two conformations of EG subunits, the straight (4DL0; green and cyan) and more bent (4EFA; lemon and pale cyan) are fitted to the three peripheral stalks. Inset, region of the EM map showing the interaction of modeled subunit H (Ser-381) (yellow) through the sulfhydryl cross-linker 4-(N-maleimido)benzophenone (62) (stick; green) to the S. cerevisiae subunit F(1–94) (Glu-31). Left panel, schematic representation of the structures of the individual S. cerevisiae subunits C (1U7L; salmon), F(1–94) (4IX9, blue), H (1HO8, brown), and EG in two conformations, straight (4DL0; green and cyan) and bent (4EFA; lemon and pale cyan).

In the last decade, the structures of the individual eukaryotic V-ATPase subunits C (14), E (15–17), F(1–94) (18), G (15, 19, 20), and H (21) were determined, all from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae enzyme. These structures fit into a cryo-EM map of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase as shown in Fig. 1.

During catalysis the central stalk subunit F is proposed to undergo structural alterations by interacting with subunits A, B, D, and d in a nucleotide-dependent manner (22, 23). Most recently, we determined the crystallographic structure of the N-terminal 94 amino acids domain (ScF(1–94)) of the 118-residue S. cerevisiae subunit F (18). ScF(1–94) has an elliptical shape with a size of 30 × 16 × 38 Å (Fig. 1). It contains four-parallel β-strands, which are intermittently surrounded by four α-helices forming an egg-shaped structure. Unknown so far are the structures of the C-terminal domain of ScF as well as the structure of the entire subunit D. Both are described as the key elements in coupling ATPase activity in the A3B3 headpiece via a rotary-like mechanism with ion conduction in the VO part (24). Furthermore, subunit F has been proposed to transmit the signal for V1VO disassembly by interacting with stalk subunit H and the nucleotide-binding subunits A and B in the V1 part (4, 11, 18).

Understanding the enzymatic and regulatory functions of the two stalk subunits D and F requires knowledge of their high resolution structure. Here, we present the first structural models of the S. cerevisiae DF assembly (ScDF) at a resolution of 3.1 Å. The structural models of ScDF show the molecular interactions between both subunits as well as the catalytic A3B3 headpiece of the V-ATPase, and they provide important insight into an interface essential for the structural integrity of the enzyme. Finally, the new structures shed light onto the coupling events of ATP-dependent ion pumping and reversible disassembly.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Biochemicals

Chemicals of analytical grade were obtained from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany), Merck, Sigma, or Serva (Heidelberg, Germany). Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography resin and chemicals for SDS-PAGE were obtained from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) and Bio-Rad, respectively.

Purification of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase DF Assembly

Cloning, production, and purification of the recombinant DF heterodimer of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase (ScDF) has been described previously (18). The selenomethionine DF assembly was produced in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) cells by growing 5-ml culture cells overnight at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, which contained 100 μg/ml carbenicillin. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation (6,000 × g), resuspended in M9 minimal media, pelleted (1,000 × g), and resuspended twice. The cell suspension was used to inoculate 1 liter of pre-warmed (37 °C) M9 minimal media and grown at 37 °C. When the A600 of 0.6 was obtained, the minimal media were supplemented with 100 mg/liter lysine, phenylalanine, and threonine, 50 mg of isoleucine, leucine, and valine, and 25 mg of selenomethionine and incubated for 15 min. Thereafter, protein production was induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.8 mm, and growth was continued at 37 °C for 4 h. The selenomethionine-substituted ScDF was purified as described earlier (18), except that 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) was used in all buffers to avoid oxidation of selenium.

Crystallization of the DF Heterodimer

Crystallization of the native ScDF was done using the vapor diffusion method and commercially available screens. Hanging drops were set up by mixing 1 μl of the purified ScDF (5 mg/ml and 8 mg/ml) in buffer, 50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.5, 250 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA with 1 μl of the precipitant solution and incubated at 18 °C against 500 μl of mother liquor. Initial crystals were obtained in Hampton research crystal screen 1, condition 11 (0.1 m sodium citrate tribasic dehydrate, pH 5.6, 1.0 m ammonium phosphate monobasic). Good diffraction quality crystals were obtained in optimized condition of 0.1 m sodium citrate tribasic dehydrate, pH 5.6, 1.2 m ammonium citrate monobasic. The crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen at 100 K in crystallization buffer containing 25% (v/v) glycerol. For the selenomethionine ScDF, the final buffer was exchanged with 50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.5, 250 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, and 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Further optimization was done using additives from Hampton research, and the crystals, grown in the presence of 3-(1-Pyridino)-1-propane sulfonate (NDSB), were finally used for structural studies.

Data Collection and Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data

X-ray diffraction data for the native ScDF crystal was collected at the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Centre, Taiwan. Initial attempts to get a solution by molecular replacement, using the subunit DF structures of related Enterococcus hirae A-ATP-synthase (3AON and 3VR4 (25, 26)) and Thermus thermophilus (3W3A (27)), as well as the S. cerevisiae mutant structure, ScFI-94 (4IX9) (18), were unsuccessful. Therefore, selenomethionine crystals of ScDF were produced as described above, and multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) data were collected at the synchrotron beamline 13B1 of the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Centre in Taiwan using the Q315 detector. Three datasets were collected to a 3.1 Å resolution from a single crystal at the appropriate inflection, peak, and remote wavelengths that were selected from a selenium absorption spectrum. Data were collected as a series of 0.5 oscillation images covering a crystal rotation range of 200 on cryo-cooled crystals at 100 K. The MAD dataset was indexed, integrated, and scaled using the HKL2000 suite of programs (28). The data were cut off at 3.1 Å based on the CC1/2 statistics (29) (correlation coefficient between two random halves of the data set where CC1/2 >10%) to determine the high resolution cutoff for our data. Phenix (30) was used to compute the CC1/2 (78.7% for the highest resolution shell and 99.9% for the entire data set), supporting our high resolution cutoff determination.

The structure of ScDF was phased by the single wavelength anomalous diffraction method, using the peak dataset at 3.1 Å of the selenomethionine MAD data set. The Shelx program (31) and the Autorickshaw server were used to identify 5 out of 14 selenium sites in the protein (32, 33). The resulting phases were channeled into Pirate for density modification (34), and automated model building was done using Buccaneer of CCP4 suite (35). Manual correction of the model was done with COOT (36), and refinement was carried out using REFMAC of the CCP4 suite (37). A final check on the stereochemical quality of the final model was assessed using PROCHECK (38) and Molprobity (39), and any conflicts were addressed. Molprobity analysis indicated that the overall geometry of the final model was ranked in the 100th percentile (Molprobity score of 1.69). The clash score for all atoms was 2.87 corresponding to a 100th percentile ranking of structures of comparable resolution. All the figures were drawn using the program PyMOL (40). The structure refinement statistics are given in Table 1. The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 4RND.

TABLE 1.

Statistics of data collection, processing, and refinement for SeMet ScDF

| Peak | Inflection | Remote | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.978 | 0.979 | 0.963 |

| Space group | P61 | P61 | P61 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | |||

| a = b (Å) | 168.063 | 168.34 | 168.47 |

| c (Å) | 128.629 | 128.68 | 128.86 |

| α = β (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| γ (°) | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Solvent content (%) | 80.27 | 80.31 | 80.38 |

| No. of molecules in the asymmetric unit | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30–3.1 (3.25–3.17)a | 30–3.5 (3.73–3.6)a | 30–3.6 (3.73–3.6)a |

| Total no. of reflections | 425,295 | 79,622 | 72,990 |

| No. of unique reflections | 38,345 | 27,857 | 21,998 |

| I/σa | 19.1 (1.2) | 10.1 (0.5) | 9.6 (1.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.0 (90.1) | 94.6 (73.6) | 97.9 (93.6) |

| Rmergeb (%) | 9.9 (84.9) | 12.1 (73.7) | 17.0 (82.7) |

| Multiplicity | 11.4 (8.7) | 4.8 (4.0) | 4.7 (3.8) |

| CC1/2 | 99.9 (78.7) | 99.9 (69.3) | 99.9 (63.7) |

| Refinement statistics | |||

| R-factorc (%) | 20.4 | ||

| R-freed (%) | 23.2 | ||

| No. of waters | 59 | ||

| No. of glycerols | 3 | ||

| MolProbity statistics | |||

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97.37 | ||

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 | ||

| Clash score | 2.87 | ||

| r.m.s.d. | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | ||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.043 | ||

| Overall B values | |||

| From Wilson plot (Å2) | 56 | ||

| Mean B value (Å2) | 37 | ||

a Values in parentheses refer to the corresponding values of the highest resolution shell.

b Rmerge = ΣΣi|Ih − Ihi|/ΣΣiIh, where Ihis the mean intensity for reflection h.

c R-factor = Σ‖Fo| − |Fc‖/Σ|Fo|, where Fo and Fc are measured and calculated structure factors, respectively.

d R-free = Σ‖Fo| − |Fc|/Σ|Fo|, calculated from 5% of the reflections selected randomly and omitted during refinement.

Solution Small Angle X-ray Scattering of Subunit F

SAXS data of recombinant subunit F of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase (ScF), purified according to Basak et al. (18), were measured with the Bruker NANOSTAR SAXS instrument, equipped with a MetalJet x-ray source and Vantec 2000 detector system (41). The x-ray radiation was generated from a liquid gallium alloy with microfocus x-ray source (Kα = 1.3414 Å with a potential of 70 kV and a current of 2.857 mA). The x-rays are filtered through Montel mirrors and collimated by the two-pinhole system. The sample to detector distance was set at 67 cm, and the sample chamber and x-ray paths were evacuated. Protein concentrations of 2.0 and 4.2 mg/ml of ScF have been measured at 15 °C with a sample volume of 40 μl in a vacuum tight quartz capillary. The buffer containing 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, and 5 mm EDTA was measured twice. For each measurement, a total of six measurements at 5-min intervals were recorded. The data were flood-field, spatially corrected, and processed using the inbuilt SAXS software. The data were tested for possible radiation damage by comparing the six data sets, and no changes were detected. The scattering of the buffer was subtracted, and the difference curves were scaled for the concentration. All the data processing steps were performed automatically using the program package PRIMUS (42). The experimental data obtained for different concentrations were analyzed for aggregation and folding state using Guinier (43) and Kartky plots (44), respectively. The forward scattering I(0) and the radius of gyration Rg were evaluated using the Guinier approximation (43). These parameters were also computed from the entire scattering patterns using the indirect transform package GNOM (45), which also provided the distance distribution function p(r), which gives the maximal particle diameter, Dmax. The hydrated volume Vp, used to estimate the molecular mass of globular proteins, was computed using the Porod invariant. Empirically, it was found that the hydrated volume in cubic nanometers should numerically be between 1.5 and 2 times the molecular mass in kilodaltons (46). Low resolution models of subunit F were built by the program DAMMIN (47). Ab initio solution shapes of subunit F were obtained by superposition of 10 independent model reconstructions with the program package SUBCOMP (48) and building an averaged model from the most probable one using the DAMAVER program (49).

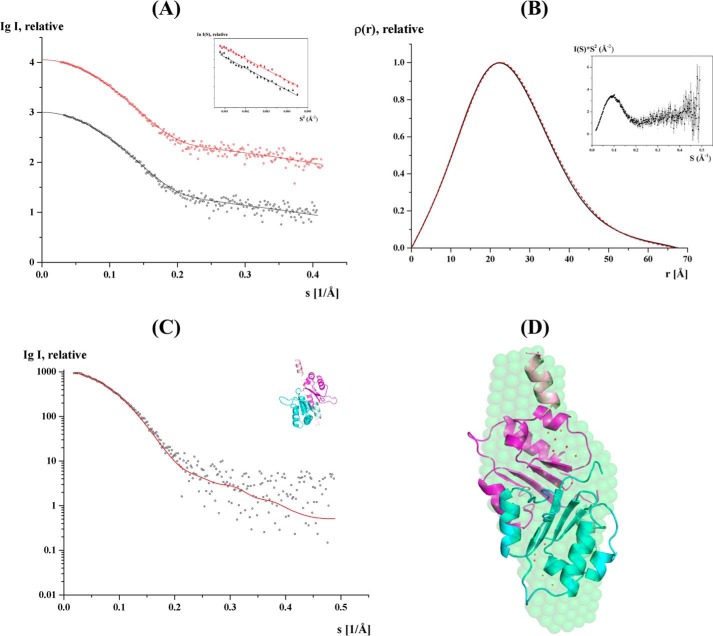

Comparison of the experimental scattering curve with the theoretical scattering curves calculated for the monomer of subunit F with both conformations, parallel and perpendicular, were performed with CRYSOL (50). The dimer of subunit F in parallel or perpendicular conformation and a dimer model containing both conformations in one were modeled based on the truncated crystal structure of S. cerevisiae F(1–94) (Protein Data Bank code 4IX9 (18)), and their theoretical scattering curves were computed. Analysis showed that the dimer (parallel χ = 1.85; perpendicular χ = 2.05; both χ = 1.93) had a better fit than the monomer (parallel χ = 2.20; perpendicular χ = 2.08). The models were then used in OLIGOMER (42) to find the best fit to a multicomponent mixture of proteins. A fit of χ = 1.62 was achieved when both conformations of the dimer were present in equal amounts (perpendicular to parallel conformation of 51:49%), and no monomers were present. A dimer model was generated using CORAL (52) allowing flexibility for the loop (95–105) between the globular domain and the C-terminal helix (52).

RESULTS

Crystallographic Data of the ScDF Heterodimer

The complex of the subunits D (256 residues) and F (118 residues) of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase was crystallized in the hexagonal space group P61, and its structure was determined by selenium SAD method and refined to 3.1 Å resolution. Assuming two ScDF molecules in the asymmetric unit, the solvent content was 80.27% and the Vm was 6.09 Å3 (53). The two molecules of ScDF (called ScDF1 and ScDF2) are arranged in a head to tail orientation in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 2A). The final asymmetric unit consists of two molecules of ScDF and 59 molecules of water and 3 glycerol molecules (Fig. 2A). The final R-factor and R-free (calculated with 5% of reflections that were not included in the refinement) were 0.20 and 0.22, respectively. In the ScDF1 and ScDF2 molecules, the residues 27–204 and 37–203 of the 256 amino acid subunit D were assigned, respectively. In the case of ScDF1, all 118 residues of subunit F were resolved in the structure, whereby amino acids 1–116 could clearly be assigned in the ScDF2 molecule. The side chain densities for all the amino acids are well resolved. Ramachandran restraints were turned on during real space refinement in Coot (36). Validation with the ERRAT server (54) gave an overall quality factor of 94%.

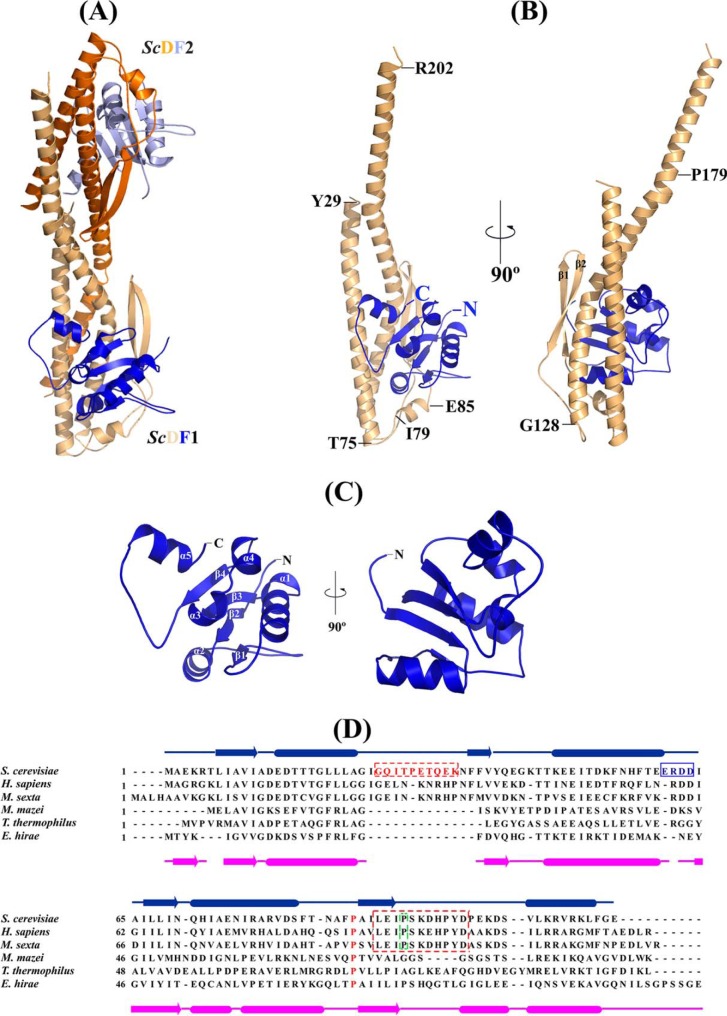

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure of S. cerevisiae subunit DF complex. A, crystal structure of DF complex of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase in an asymmetric unit; ScDF1 is shown in wheat and blue, and ScDF2 is shown in orange and light blue, respectively. B, schematic representation of the ScDF1 complex; ScD and ScF are shown in wheat and dark blue, respectively. Proline 179, which is conserved in all the eukaryotic ATP synthases, is labeled. C, schematic representation of ScF1 (dark blue), with the unique C terminus helix conformation and the α-helices and β-strands labeled. D, sequence alignment of subunit F from different ATPases. The secondary structure elements of subunit F from E. hirae and S. cerevisiae are shown. The conserved sequence in the eukaryotic ATP synthase is shown within the box. The 26GQITPETQEK35 loop of the F subunit is highlighted in red. The conserved Pro-89 is highlighted in red and is present in V-ATPases as well as A-ATP synthases. Proline 95, which is conserved in eukaryotic V ATPases, is highlighted by a green frame.

Overall Structure of ScDF

The overall structure of S. cerevisiae DF assembly is shown in Fig. 2B. Subunit D of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase consists of a long pair of α-helices (110 Å), connected by a short helix (79IGYQVQE85) as well as a β-hairpin region, which is flanked by two flexible loops. The long pair of helices is composed of the N-terminal α-helix, which commences from Tyr-29 to Thr-75, and the C-terminal helix, containing residues Gly-128 to Arg-202. The remaining portion containing residues 76–127 is composed of a short β-hairpin region formed by residues Phe-92 to Ile-113, two flexible loops, and a short α-helix. The N-terminal helix consists of both hydrophobic residues and hydrophilic residues and is slightly basic. The short helix (79IGYQVQE85) is slightly acidic (Fig. 2B). The β-hairpin region contains hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues. The C-terminal helix mostly contains acidic residues. There is a slight bend in the C-terminal helix near the hinge region where a conserved Pro-179 is located. In comparison, a clear break can be seen in the same position of this helix near the proline-induced hinge region of the ScDF2 molecule. The r.m.s.d. value between the D subunit of the ScDF1 and ScDF2 molecule for 161 Cα atoms is 6.3 Å, compared with an r.m.s.d. of 1.0 Å for the first 117 equivalent Cα atoms of subunit D. These data indicate that movement of the C-terminal helix occurs around the hinge region of subunit D with maximum movement beginning after residue Ala-155.

The 118-residue-long subunit F of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase reveals four parallel β-strands, which are enveloped by five α-helices (Fig. 2C). The four β-strands (β1–β4) are arranged parallel to each other and are connected by five α-helices (α1–α5). In both molecules, the conformation is similar except for the α5-helix. The four β-strands (β1, Leu-7 to Ala-12; β2, Phe-37 to Val-39; β3, Ile-64 to Asn-70, and β4, Ala-90 to Ile-94) and the four α-helices (α1, Glu-14 to Ala-23; α2, Lys-47 to Glu-60; α3, Gln-71 to Glu-75, and α4, Arg-78 to Ser-83) form the N-terminal globular domain. This N-terminal domain is connected via a flexible loop of 12 residues (Pro-95 to Asp-106) to the C-terminal α-helix (α5, residues Ser-107 to Leu-115). As confirmed by amino acid sequence alignment, the subunit F structure contains a unique loop between α1 and β2 (26GQITPETQEK35) and a highly conserved loop with a 60ERDD63 motif between α2 and β3, which are present only in eukaryotic V-ATPases (Fig. 2D). The C-terminal helix α5 consists of mostly positively charged residues (107SVLKRVRKL115). The r.m.s.d. (Cα) between the 115 residues of subunit F of the ScDF1 and ScDF2 molecule is 3.5 Å. In comparison, the r.m.s.d. of the N-terminal 94 Cα atoms of subunit F in both molecules (ScDF1 and ScDF2) is 0.3 Å, reflecting that the maximum differences are prevailing in the C-terminal region. As shown in Fig. 4A, the flexible loop (Pro-95 to Asp-106) of subunit F in the ScDF1 molecule is bent at residue Lys-105, causing a perpendicular orientation of its C-terminal helix α5 relative to the N- and C-terminal helices of subunit D. In comparison, in the ScDF2 molecule the C-terminal helix α5 of subunit F is almost parallel to the N- and C-terminal helices of subunit D.

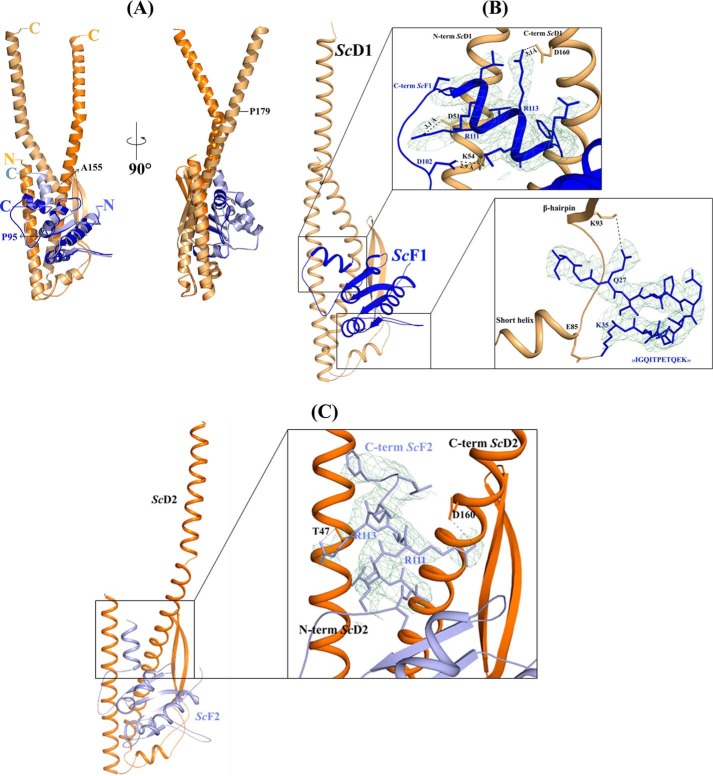

FIGURE 4.

Intermolecular interactions of DF assembly. A, superimposition of the ScDF1 (wheat and blue) with ScDF2 molecule (orange and light blue). Residues Ala-155 and Pro-179 of subunit D and Pro-95 of subunit F are labeled. B, interactions in the ScDF1 molecule. The interaction of the very C terminus of ScF1 compact form with the N and C terminus of ScD1, and the interaction of the loop 25IGQITPETQEK35 of ScF1 with the loop between the short helix and β hairpin region of ScD1 are shown in the inset, respectively. C, ScDF2 molecule, where the ScF2 C-terminal helix is almost parallel to the N- and C-terminal helix of ScD2, is shown as schematic. Inset, interactions of the C-terminal helix of ScF2 is presented. The electron density omit map (contoured at 2σ) is shown in green mesh.

The overall surface electrostatic potential of ScDF is composed of both acidic and basic residues except the exposed N- and C-terminal helix of subunit D, which are basic and predominantly acidic, respectively (Fig. 3, A and B). The electrostatic potential of the bottom of ScDF is also composed of both acidic and basic residues. The hydrophobic residues are mostly found in the interface region of subunits D and F (Fig. 3A). In ScD the hydrophobic site includes residues Leu-31, Leu-32, Lys-33, Leu-39, Phe-43, Thr-47, Ile-50, Met-57, Met-61, Ala-64, Leu-68, Val-71, and Ala-74 of the N-terminal α1-helix; amino acids Phe-92, Val-94, Ala-96, Val-101, Val-104, Leu-106, and Phe-109 of the β-hairpin region; and residues Val-143, Thr-145, Leu-146, Leu-149, Leu-152, Phe-156, Ile-157, and Leu-159 of the C-terminal helix α3. In the case of subunit F, the hydrophobic site is formed by the residues Ile-8, Ala-9, Val-10, Ile-11 and Ala-12 located of β1; Ile-64, Ala-65, Ile-66, Leu-67 and Leu-68 on β3; Ala-90, Ile-91, Leu-92, and Ile-94 of β4; and the residues Gly-19, Leu-20, Leu-21, and Leu-22 of the N-terminal helix α1.

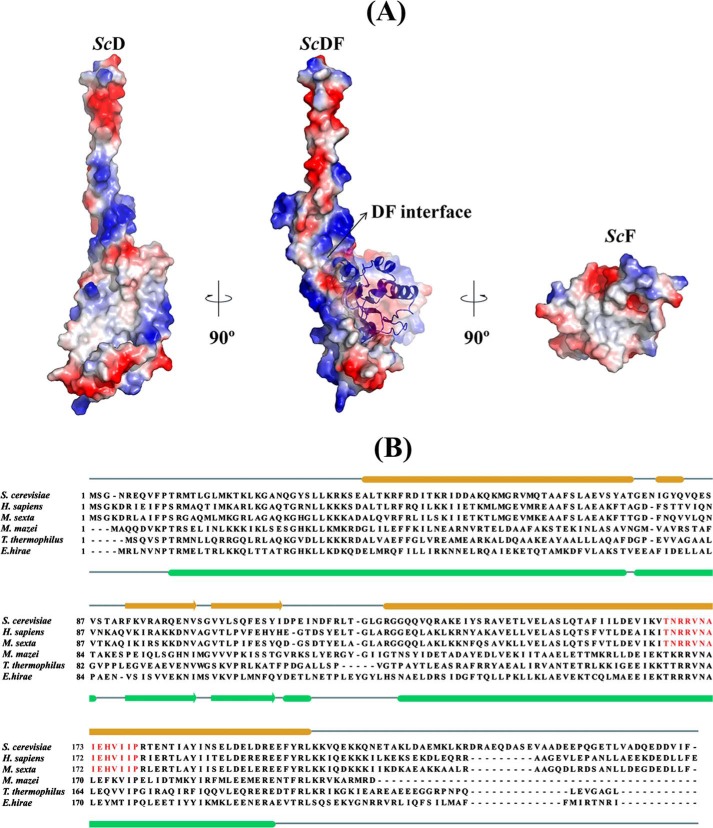

FIGURE 3.

Surface electrostatic and hydrophobicity of DF assembly and sequence comparison of subunit D. A, surface electrostatic potential of the ScDF complex with ScF shown as schematic and the DF interface labeled by an arrow is shown in the center. Surface electrostatic potential of ScD reveals that the interacting surface with ScF is mostly hydrophobic, whereas the exposed N and C termini of ScD are composed of basic and predominantly acidic residues (left). The interacting surface of ScF is predominantly hydrophobic (right). The electrostatic potential surfaces were calculated using APBS (56) and mapped at contouring levels from −3 kT (blue) to 3 kT (red). B, sequence alignment of subunit D from different V-ATPases and ATP synthases, respectively. The secondary structure elements of subunit D of the E. hirae A-ATP synthase and the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase are shown. The conserved sequence in the eukaryotic V-ATPases is highlighted in red.

Interaction of Subunits D and F

As revealed by Fig. 4A, the S. cerevisiae subunit F is bound to the lower middle part of subunit D. The hydrophobic residues from the C-terminal helix α3 of subunit D and α1 as well as β4 of subunit F, respectively, generate the major contacts of the hydrophobic interface of both subunits. A second point of interaction is formed by the 26GQITPETQEK35 loop, which is in close proximity with the loop residues 85ESVSTARFK94 of subunit D, which span the short helix (79IGYQVQE85) and the β-hairpin (Fig. 4B). In addition, the C-terminal helix α5 of subunit F of the ScDF1 and ScDF2 molecule is interacting with the N- and C-terminal helix of subunit D. In the case of the ScDF1 molecule, the interaction of subunit D and F occurs via the amino acids Asp-51, Asp-160, and Lys-54 and Arg-111, Arg-113, and Asp-102 of subunits D and F, respectively (Fig. 4B). In comparison, residues Asp-160 and Thr-47 interact with Arg-111 and Arg-113 of subunits D and F for the ScDF2 molecule (Fig. 4C). The existence of these two conformations of helix α5 of subunit F relative to the termini of subunit D indicates a very flexible conformational switching between an extended and slight compact conformation of subunit F.

Subunit F in Solution Studied by SAXS

The two conformations of the C terminus of the ScF structures may also represent intermediate conformations that arise during movement about the hinge regions. To understand whether subunit F is able to undergo structural alterations in solution, SAXS experiments were performed. SAXS patterns of recombinant subunit F of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase (ScF) were recorded at 2.0 and 4.2 mg/ml, which showed similar final composite scattering curves (Fig. 5A and Table 2). The Guinier plots at low angles are linear and revealed good data quality with no indication of protein aggregation (Fig. 5A, inset). The Kratky plot (I(s) × s2 versus s) (Fig. 5B, inset) shows a bell-shaped peak at low angles indicating a well folded protein. The radius of gyration (Rg) values from the Guinier approximation were consistent at the two concentrations measured with a value of 19.3 ± 0.6 Å. The distance distribution functions (p(r)) were similarly shaped for the concentrations used (Fig. 5B), and the maximum particle dimension is Dmax = 67.5 ± 3 Å. The gross shape of the subunit F was ab initio reconstructed and had a good fit to the experimental data in the entire scattering range and had a discrepancies of χ2 = 0.951. Ten independent reconstructions produced similar envelope with normalized spatial discrepancy of 0.65 ± 0.01, and the average structure is shown in Fig. 5D.

FIGURE 5.

Solution x-ray scattering studies of ScF. A, small angle x-ray scattering pattern (○) and its corresponding experimental fitting curves (- - -) for the concentrations 2.0 (black) and 4.2 (red) mg/ml. The scattering curves of ScF are displayed in logarithmic units for clarity. Inset, Guinier plots show linearity for the concentrations used, indicating no aggregation. B, pair-distance distribution function P(r) of ScF at 2.0 (black) and 4.2 (red) mg/ml. Inset, Kratky plot of ScF SAXS data at 4.2 mg/ml. C, fit of the scattering profile of the CORAL model with the best χ value of 1.24 (red) to the experimental scattering pattern of ScF at 2 mg/ml (black). D, CORAL model generated is superimposed with the solution shape of ScF. The compact monomer of the dimer is colored cyan, and the extended monomer is colored magenta. The C-terminal helices are colored lighter and the flexible regions are represented as dots and colored red.

TABLE 2.

Data collection and scattering derived parameters for ScF using SAXS

| Data collection parameters | |

| Instrument | Bruker NANOSTAR |

| Beam geometry | 100-μm slit |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.3414 |

| q range (Å−1) | 0.01–0.5 |

| Exposure time (min) | 30 |

| Concentration range (mg/ml) | 2 and 4.2 |

| Temperature (K) | 288 |

| Structural parametersa | |

| I(0) (cm−1) (from P(r)) | 999.9 ± 7 |

| Rg (Å) (from P(r)) | 19.6 ± 0.3 |

| I(0) (cm−1) (from Guinier) | 1007 ± 7 |

| Rg (Å) (from Guinier) | 19.3 ± 0.6 |

| Dmax (Å) | 67.5 ± 3 |

| Porod volume estimate (Å3) | ∼32,831 |

| Dry volume calculated from sequence (Å3) | 15,903 |

| Molecular mass determinationa | |

| Calculated monomeric Mr from sequence | 13,144 |

| Mr from I(0) | 21,305 |

| Mr from SAXS MoW | 24,100 |

| Mr from excluded volume | 23,200 |

| Software employed | |

| Primary data reduction | SAXS |

| Data processing | PRIMUS |

| Ab initio analysis | DAMMIN |

| Validation and averaging | DAMAVER |

| Rigid body modeling | CORAL |

| Computation of model intensities | CRYSOL |

| Three-dimensional graphics representations | PyMOL |

a Data are reported for 2 mg/ml measurements.

The molecular mass as determined by the I0 value, Porod hydrated volume, and from the SAXS MoW server (55) ranged from 21 to 24 kDa, indicating the presence of a dimer or a mixture of both monomer and dimer in solution. Comparison of the theoretical scattering curves for the monomer and dimer in both parallel and perpendicular conformations in CRYSOL confirmed the presence of dimer formation with the fit being improved when both conformations of the dimer were present in equal amounts. Based on the above observation, a dimer model was generated using CORAL (52), which allows flexibility for the loop with the residues 95–105 between the globular domain and the C-terminal helix α5 of ScF. This program performs modeling of complexes against the experimental SAXS data using a combined rigid body for the atomic structures of the domains and the ab initio modeling of the unknown loop regions. The CORAL model fits with χ = 1.24 and reveals that the two conformations (parallel and perpendicular) co-exists in the same dimer with the C terminus being more compact in one and more extended in another molecule of the dimer (Fig. 5, C and D). These data reveal that the C-terminal region of subunit F can undergo dynamic movements in solution.

DISCUSSION

The crystallographic structure of subunit F of the ScDF1 and ScDF2 molecule of the S. cerevisiae V-ATPase, respectively, and the recently determined structure of the N-terminal domain of subunit F, ScF(1–94) ((18) including the N-terminal residues 1–94) show an r.m.s.d. value 1.42 and 1.5 Å, respectively, indicating no major difference in the globular domain of these structures. The present entire structure (118 amino acids) of ScF in the ScDF1 molecule as well as the 116-amino acid structure of subunit F in the ScDF2 molecule give insights of the important C terminus with its flexible loop (Pro-95–Asp-106) and helix α5. The comparison of both subunit F structures (Fig. 4A) reveals differences mainly in the C terminus of both molecules indicated by the high r.m.s.d. value (3.58 Å). The Pro-95–Asp-106-loop with its bent feature at Lys-105 enables structural rearrangements, leading to a perpendicular or parallel orientation of helix α5 relative to the N- and C-terminal helix of subunit D (Fig. 4A). The solution x-ray scattering data of S. cerevisiae V-ATPase subunit F confirm the flexibility of the Pro-95–Asp-106 loop and demonstrate that this loop and helix α5 are able to undergo a rearrangement from a compact subunit F to an extended C-terminal formation (Fig. 5D). These data extend the recent findings of 15N-(1H) heteronuclear NOE studies on ScF, demonstrating that helix α5 with the adjacent Pro-95–Asp-106 loop is flexible in solution (18). As demonstrated by the structure of the ScDF1 and ScDF2 molecules, the flexibility of the C-terminal segment of ScF leads to different interactions with the rotary subunit D, in which the C terminus of subunit F is either in proximity to the subunit D residues Asp-51, Lys-54, and Asp-160 (ScDF1 molecule) or with the subunit D amino acids as Thr-47 and Asp-160 (ScDF2 molecule; Fig. 4C). We showed most recently that subunit F of the eukaryotic S. cerevisiae V-ATPase activates ATP hydrolysis of the related archaea A1 complex, in which ScF was reconstituted with the A3B3D complex of the archaeal Methanococcus mazei Gö1 A-ATP synthase.5 In the same set of experiments, it was demonstrated that no A3B3DF complex could be formed when the C-terminal truncated ScF(1–94) was used, which underlines the need of the C terminus of subunit F for proper assembly and enzyme activity.

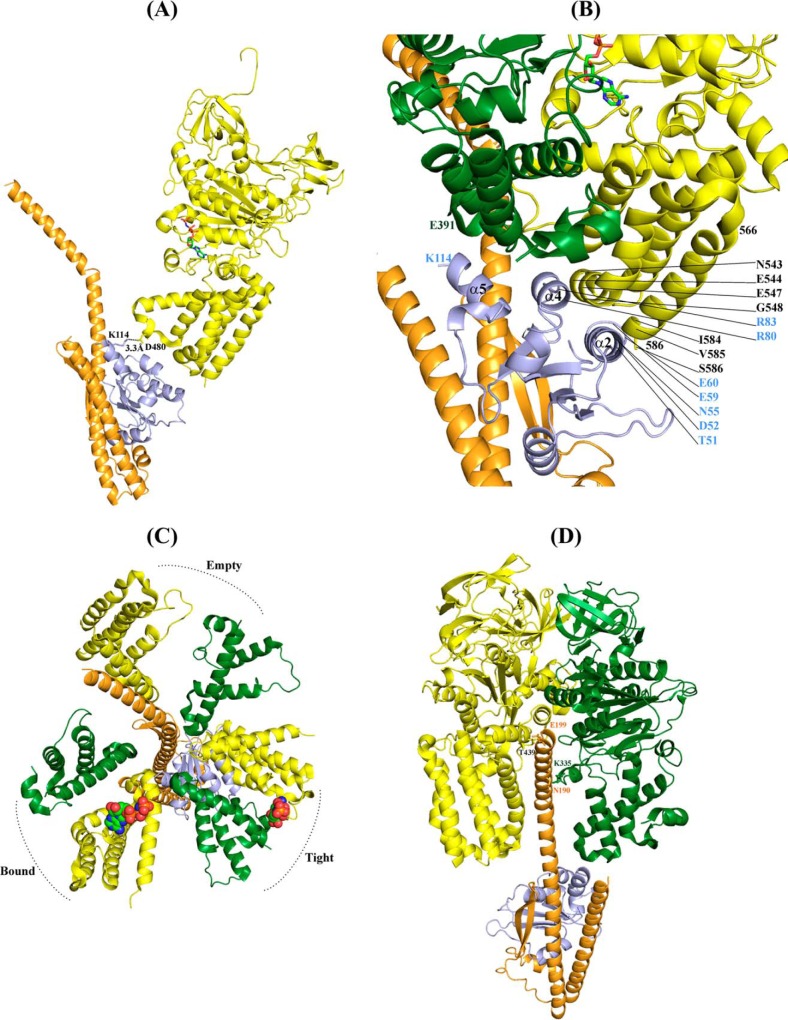

The question arises to how the Pro-95–Asp-106-loop with helix α5 of ScF connects the activation of ATP hydrolysis in the catalytic A3B3 headpiece of the enzyme. When the presented ScDF1 and ScDF2 molecules, respectively, were docked into the nucleotide-bound A3B3 headpiece of the related E. hirae A-ATP synthase (26), no interaction between the compact form of ScF (ScDF1 molecule) and the nucleotide-binding subunits A or B was observed. In comparison, Lys-114 of the extended α5 helix of subunit F (ScDF2 molecule) comes in close proximity (3.3 Å) to Asp-480 of the AMP-PNP-bound catalytic A subunit (Fig. 6A), allowing a direct coupling between the catalytic A subunit and the central stalk subunit F. The subunit A–F arrangement confirms the requirement for the very C terminus of subunit F, as described by the C-terminal truncated ScF(1–94) above.5

FIGURE 6.

Fitting of the ScDF onto the DF subunits of the nucleotide-bound E. hirae A1-ATP synthase structure (3VR6 (26)). A, extended C terminus of ScF (ScDF2 molecule) comes in contact with the EhA with the residue Lys-114 of ScF2 having electrostatic interaction with Asp-480 of EhA. Only one subunit A from E. hirae hexamer is shown for clarity. The nucleotide is shown in stick representation. B, close view of the various interactions of the extended ScF with EhA and B in the tight form of the A-B interface when ScDF2 is rotated by 80°. The α2 and α4 of ScF interacts with the C-terminal domain of EhA and α5 interacts with EhB. C, top view showing the C-terminal domain of subunit A and B from E. hirae A1-ATP synthase and the position of ScDF2 after 80° rotation. ScF is in close proximity to the tight form of the nucleotide-binding site, and ScD lies between the empty and bound forms. D, interaction of ScD with subunits A and B of E. hirae. For clarity other subunits are removed from the hexamer.

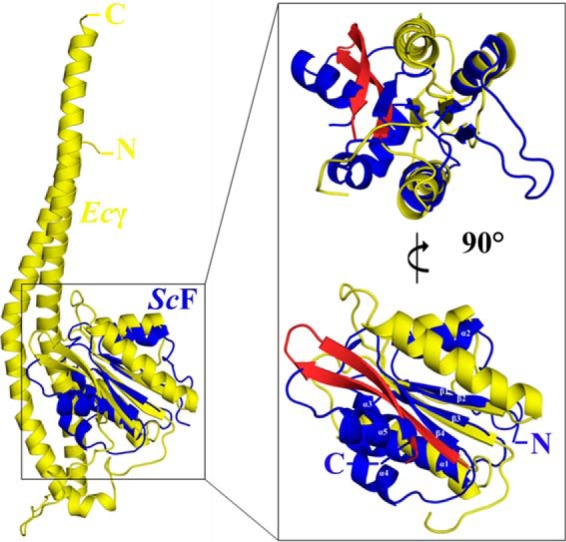

As shown for the related bacterial F-ATP synthase, the central stalk subunits γϵ in α3β3γϵ complexes, which are proposed to be homologues to the DF assembly, and the A3B3 headpiece of V-ATPases, rotate in 80° and 40° substeps (57–60), or as most recently shown for the human mitochondrial F1-ATPase subunit, γ rotates in three 120° steps with sub-steps of 0–65, 65–90, and 90–120° (61). Here, we moved the DF assembly inside the A3B3 shaft by 80° and observed that amino acid Lys-114 of the extended helix α5 of ScF comes in the neighborhood to Glu-391 of subunit B, belonging to the C-terminal region 388VLGESALSDI397 of subunit B (Fig. 6, B and C), which occupies a similar position to the so-called DELSEED region of the nucleotide-binding subunits α and β of F1F0-ATP synthases (62). At the same time the subunit F residues Arg-80, Arg-83, and Thr-51, Asp-52, Asn-55, Glu-59, Glu-60 of helix 2 and helix 4, respectively, are close to subunit A residues Ile-584, Val-585, Ser-586, and Asn-543, Glu-544, Glu-547, Gly-548, respectively (Fig. 6B). These interactions of subunit F with several subunit A and B residues may change the nucleotide-binding and ATP cleavage steps in the catalytic subunit A. The 80° movement of the DF assembly also brings the bended C-terminal helix of ScD in the interface of the nucleotide-free subunits A and B (Fig. 6D), where the amino acids Asn-190 and Glu-199 come in proximity to the residue Thr-439 and Lys-335 of subunit A and B, respectively. In the future, single molecule rotation studies of the S. cerevisiae A3B3DF complex may provide more details about sub-steps of the central stalk subunits DF inside the V1-ATPase. This will be of great interest, because subunit F and ϵ reveal no structural similarity, and subunits D and γ are similar in respect to their N- and C-terminal helices. When the globular domain of the E. coli subunit γ (Ecγ) was superimposed with ScF, a similar fold of both domains could be observed with respect to the central parallel β-sheet (β1–β3), which is flanked by the α-helices α1 and α2 on both sides of its plane (Fig. 7). The sequence similarity of the globular domain of Ecγ and ScF is 18.9%. Future studies may show whether subunit γ is a fused form of subunits D and F of eukaryotic V-ATPases as well as the related and evolutionary older A-ATP synthases, respectively (5).

FIGURE 7.

Superposition of subunit γ of the E. coli F-ATP synthase with ScF. Overall superposition of the E. coli subunit γ ((51) 3OAA; yellow) with ScF subunit (4RND; blue). Inset, globular domain of the γ subunit shares a similar fold with ScF. The α-helices and β-strands of ScF are labeled. The β-hairpin of Ecγ is shown in red. Two views of the superposition, rotated by 90°, are shown for clarity.

The structural differences observed in the C terminus of subunit F in the ScDF1 and ScDF2 molecules of our presented structure depicts not only two mechanistically relevant conformations but also shows the stabilizing effect in the DF complex via the formation of salt bridges at the interface of the C termini of both subunits. The perpendicular orientation of ScF helix α5 relative to the N- and C-terminal helix of subunit D leads to the interaction of Asp-51 and Asp-160 of ScD (ScDF1 molecule) with amino acids Arg-111 and Arg-113 of subunit D, respectively (Fig. 4B). This may stabilize the coiled coil formation during rotary steps of the central DF assemblage. As shown for the E. hirae A-ATP synthase, depletion of the C-terminal residues of subunit F led to insolubility of subunit D, indicating the stabilizing role of the C terminus of subunit F in DF formation (26).

As described recently and confirmed here, subunit F of eukaryotic V-ATPases contains the conserved 26GQITPETQEK35 loop (Fig. 4B), which faces the C-terminal serine residue Ser-381 of subunit H (18), revealed to be involved in F-H cross-linking formation (Fig. 1) (18, 63). It has been proposed that in the process of V1 and VO dissociation, the flexible C-terminal domain of subunit H moves slightly closer to its nearest neighbor, the exposed 26GQITPETQEK35 loop of subunit F, where it causes conformational changes, leading to an inhibitory effect of ATPase activity in the V1-ATPase (18, 63). The present ScDF structure shows for the first time that the unique 26GQITPETQEK35 loop of ScF is within 4 Å of the 85ESVSTARFK93 loop of ScD. The two hydrogen bonding interactions between the guanidine side chain of subunit D residue Lys-93 and the carbonyl side chain of ScF residue Gln-27 as well as the one between Gln-84 of ScD and Lys-35 of ScF may play significant roles in this interaction. Interestingly, amino acid Lys-93 is highly conserved in subunit D of eukaryotic V-ATPases and is located at the beginning of the β-hairpin (Fig. 4B), which is reported to stimulate ATPase activity 2-fold in the bacterial E. hirae A-ATP synthase (25). Furthermore, amino acid Glu-85 is located at the end of the short helix (79IGYQVQE85) of subunit D. This short helix is discussed to be involved in energy coupling and to play an important role in reversible disassembly (18).

15N1H heteronuclear NOE studies on the S. cerevisiae subunit F revealed a rigid core formed by β-strands, β1 to β4, and α2 to α4. In comparison, the N- and C-terminal helices α1 and α5 with their adjacent loops 26GQITPETQEK35 and 94IPSKDHPYD102, respectively, are more flexible in solution (18). The N-terminal helix α1 of subunit F and the bottom segment of subunit D form the neighborhood with subunit d (18). It has been proposed that this area is important during the process of dissociation and reassembly of the V1 and VO sectors. In this scenario, the higher flexibility of α1 in subunit F would allow transmission of a change in subunit d during dissociation from the DF heterodimer and also the movement of subunit H closer to F, via the neighboring 26GQITPETQEK35 loop (18). In the latter case, the signal of V1VO disassembly may be communicated by the 26GQITPETQEK35 loop to the neighboring 85ESVSTARFK93 loop of ScD and in turn to the short helix (79IGYQVQE85) as well as the β-hairpin of subunit D. In addition, the 26GQITPETQEK35 loop would transfer the H to F movement via the second flexible 94IPSKDHPYD102 loop, which is adjacent to helix α5. Subsequently, helix α5 moves from its extended position away from the catalytic A subunit to the perpendicular orientation, leading to reduction of ATPase activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center, a national user facility supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan. We thank the staff at the Synchrotron Radiation Protein Crystallography Facility (supported by the National Research Program for Genomic Medicine) at beam line 13B1 for expert help with data collection. We sincerely thank Dr. Kamariah Neelagandan for data collection at the 13B1 National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center, Taiwan. We are grateful to Prof. R. Kraut and Dr. G. Tria from the School of Biological Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, Grants MOE2011-T2-2-156 and ARC 18/12 (to G. G.).

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4RND) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

D. Singh, H. Sielaff, A. Grüber, G. Biuković, L. Sundararaman, S. Bhushan, T. Wohland, and G. Grüber, submitted for publication.

- V-ATPase

- V1VO-ATPase

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- MAD

- multiwavelength anomalous dispersion

- AMP-PNP

- adenosine 5′-(β,γ-imino)triphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kluge C., Lahr J., Hanitzsch M., Bolte S., Golldack D., Dietz K. J. (2003) New insight into the structure and regulation of the plant vacuolar H+-ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 35, 377–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saroussi S., Nelson N. (2009) Vacuolar H+-ATPase–an enzyme for all seasons. Pflügers Arch. 457, 581–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beyenbach K. W., Wieczorek H. (2006) The V-type H+ ATPase: molecular structure and function, physiological roles and regulation. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 577–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishi T., Forgac M. (2002) The vacuolar (H+)-ATPases–nature's most versatile proton pumps. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 94–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marshansky V., Rubinstein J. L., Grüber G. (2014) Eukaryotic V-ATPase: novel structural findings and functional insights. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 857–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilkens S. (2001) Structure of the vacuolar adenosine triphosphatases. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 34, 191–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Graham L. A., Flannery A. R., Stevens T. H. (2003) Structure and assembly of the yeast V-ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 35, 301–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Radermacher M., Ruiz T., Wieczorek H., Grüber G. (2001) The structure of the V1-ATPase determined by three-dimensional electron microscopy of single particles. J. Struct. Biol. 135, 26–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lolkema J. S., Chaban Y., Boekema E. J. (2003) Subunit composition, structure, and distribution of bacterial V-type ATPases. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 35, 323–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muench S. P., Scheres S. H., Huss M., Phillips C., Vitavska O., Wieczorek H., Trinick J., Harrison M. A. (2014) Subunit positioning and stator filament stiffness in regulation and power transmission in the V1 motor of the Manduca sexta V-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 286–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benlekbir S., Bueler S. A., Rubinstein J. L. (2012) Structure of the vacuolar-type ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae at 11-A resolution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 1356–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Svergun D. I., Konrad S., Huss M., Koch M. H., Wieczorek H., Altendorf K., Volkov V. V., Grüber G. (1998) Quaternary structure of V1 and F1 ATPase: significance of structural homologies and diversities. Biochemistry 37, 17659–17663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Diepholz M., Venzke D., Prinz S., Batisse C., Flörchinger B., Rössle M., Svergun D. I., Böttcher B., Féthière J. (2008) A different conformation for EGC stator subcomplex in solution and in the assembled yeast V-ATPase: possible implications for regulatory disassembly. Structure 16, 1789–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drory O., Frolow F., Nelson N. (2004) Crystal structure of yeast V-ATPase subunit C reveals its stator function. EMBO Rep. 5, 1148–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oot R. A., Huang L.-S., Berry E. A., Wilkens S. (2012) Crystal structure of the yeast vacuolar ATPase heterotrimeric EGC-head peripheral stalk complex. Structure 20, 1881–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rishikesan S., Thaker Y. R., Grüber G. (2011) NMR solution structure of subunit E (fragment E(1–69)) of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae V1VO ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 43, 187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rishikesan S., Grüber G. (2011) Structural elements of the C-terminal domain of subunit E (E133–222) from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae V1VO ATPase determined by solution NMR spectroscopy. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 43, 447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Basak S., Lim J., Manimekalai M. S., Balakrishna A. M., Grüber G. (2013) Crystal and NMR structures give insights into the role and dynamics of subunit F of the eukaryotic V-ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 11930–11939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rishikesan S., Gayen S., Thaker Y. R., Vivekanandan S., Manimekalai M. S., Yau Y. H., Shochat S. G., Grüber G. (2009) Assembly of subunit d (Vma6p) and G (Vma10p) and the NMR solution structure of subunit G (G1–59) of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae V1VO ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rishikesan S., Manimekalai M. S., Grüber G. (2010) The NMR solution structure of subunit G (G61–101) of the eukaryotic V1VO ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798, 1961–1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sagermann M., Stevens T. H., Matthews B. W. (2001) Crystal structure of the regulatory subunit H of the V-type ATPase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7134–7139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grüber G., Radermacher M., Ruiz T., Godovac-Zimmermann J., Canas B., Kleine-Kohlbrecher D., Huss M., Harvey W. R., Wieczorek H. (2000) Three-dimensional structure and subunit topology of the V1 ATPase from Manduca sexta midgut. Biochemistry 39, 8609–8616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coskun U., Rizzo V. F., Koch M. H., Grüber G. (2004) Ligand-dependent structural changes in the V1 ATPase from Manduca sexta. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 36, 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Futai M., Nakanishi-Matsui M., Okamoto H., Sekiya M., Nakamoto R. K. (2012) Rotational catalysis in proton pumping ATPases: from E. coli F-ATPase to mammalian V-ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1711–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saijo S., Arai S., Hossain K. M., Yamato I., Suzuki K., Kakinuma Y., Ishizuka-Katsura Y., Ohsawa N., Terada T., Shirouzu M., Yokoyama S., Iwata S., Murata T. (2011) Crystal structure of the central axis DF complex of the prokaryotic V-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 19955–19960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arai S., Saijo S., Suzuki K., Mizutani K., Kakinuma Y., Ishizuka-Katsura Y., Ohsawa N., Terada T., Shirouzu M., Yokoyama S., Iwata S., Yamato I., Murata T. (2013) Rotation mechanism of Enterococcus hirae V1-ATPase based on asymmetric crystal structures. Nature 493, 703–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagamatsu Y., Takeda K., Kuranaga T., Numoto N., Miki K. (2013) Origin of asymmetry at the intersubunit interfaces of V1-ATPase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 2699–2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karplus P. A., Diederichs K. (2012) Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science 336, 1030–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sheldrick G. M. (2010) Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Panjikar S., Parthasarathy V., Lamzin V. S., Weiss M. S., Tucker P. A. (2005) Auto-Rickshaw: an automated crystal structure determination platform as an efficient tool for the validation of an X-ray diffraction experiment. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 61, 449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Panjikar S., Parthasarathy V., Lamzin V. S., Weiss M. S., Tucker P. A. (2009) On the combination of molecular replacement and single anomalous diffraction phasing for automated structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 1089–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cowtan K. (2000) General quadratic functions in real and reciprocal space and their application to likelihood phasing. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56, 1612–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cowtan K. (2006) The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 1002–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) COOT: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DeLano W. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.5.0.4 DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dip P. V., Kamariah N., Subramanian Manimekalai M. S., Nartey W., Balakrishna A. M., Eisenhaber F., Eisenhaber B., Grüber G. (2014) Structure, mechanism and ensemble formation of the alkylhydroperoxide reductase subunits AhpC and AhpF from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 2848–2862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Konarev P. V., Volkov V. V., Sokolova A. V., Koch M. H., Svergun D. I. (2003) PRIMUS- a Windows-PC based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 36, 1277–1282 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guinier A., Fournet G. (1955) Small-angle Scattering of X-rays (translated from French by Walker C. B.) pp. 5–78 John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 44. Glatter O., Kratky O. (eds) (1982) Small-angle X-ray Scattering. pp. 17–51, Academic Press, London, UK [Google Scholar]

- 45. Svergun D. (1992) Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J. Appl. Cryst. 25, 495–503 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mertens H. D., Svergun D. I. (2010) Structural characterization of proteins and complexes using small-angle x-ray solution scattering. J. Struct. Biol. 172, 128–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Svergun D. I. (1999) Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys. J. 76, 2879–2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kozin M. B., Svergun D. I. (2001) Automated matching of high- and low-resolution structural models. J. Appl. Cryst. 34, 33–41 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Volkov V. V., Svergun D. I. (2003) Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst. 36, 860–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Svergun D. I., Barberato C., Koch M. H. J. (1995) CRYSOL–a program to evaluate x-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J. Appl. Cryst. 28, 768–773 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shah N. B., Hutcheon M. L., Haarer B. K., Duncan T. M. (2013) The ϵ inhibited state forms after ATP hydrolysis, is distinct from the ADP-inhibited state, and responds dynamically to catalytic site ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 9383–9395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Petoukhov M. V., Franke D., Shkumatov A. V., Tria G., Kikhney A. G., Gajda M., Gorba C., Mertens H. D., Konarev P. V., Svergun D. I. (2012) New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 45, 342–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Matthews B. W. (1968) Solvent content of protein crystals. J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Colovos C., Yeates T. O. (1993) Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 2, 1511–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fischer H., de Oliveira Neto M., Napolitano H. B., Polikarpov I., Craievich A. F. (2010) Determination of the molecular weight of proteins in solution from a single small-angle x-ray scattering measurement on a relative scale. J. Appl. Cryst. 43, 101–109 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Baker N. A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M. J., McCammon J. A. (2001) Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10037–10041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yasuda R., Noji H., Yoshida M., Kinosita K., Jr., Itoh H. (2001) Resolution of distinct rotational substeps by submillisecond kinetic analysis of F1-ATPase. Nature 410, 898–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Martin J. L., Ishmukhametov R., Hornung T., Ahmad Z., Frasch W. D. (2014) Anatomy of F1-ATPase powered rotation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 3715–3720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sielaff H., Rennekamp H., Engelbrecht S., Junge W. (2008) Functional halt positions of rotary FOF1-ATPase correlated with crystal structures. Biophys. J. 95, 4979–4987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nakanishi-Matsui M., Kashiwagi S., Hosokawa H., Cipriano D. J., Dunn S. D., Wada Y., Futai M. (2006) Stochastic high-speed rotation of Escherichia coli ATP synthase F1 sector: the ϵ subunit-sensitive rotation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4126–4131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suzuki T., Tanaka K., Wakabayashi C., Saita E.-I., Yoshida M. (2014) Chemomechanical coupling of human mitochondrial F1-ATPase motor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 930–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Aggeler R., Capaldi R. A. (1996) Nucleotide-dependent movement of the ϵ subunit between α and β subunits in the Escherichia coli F1F0-type ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 13888–13891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jefferies K. C., Forgac M. (2008) Subunit H of the vacuolar (H+) ATPase inhibits ATP hydrolysis by the free V1 domain by interaction with the rotary subunit F. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4512–4519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]