Background: Csd4 is required for the helical shape of Helicobacter pylori.

Results: Csd4 activity relies on a Gln-zinc ligand to cleave cell wall tripeptides and produce helical shape.

Conclusion: Carboxypeptidase activity can be achieved with a Gln, His, and Glu zinc coordination.

Significance: Csd4 represents a new subfamily of carboxypeptidases.

Keywords: Carboxypeptidase, Cell Wall, Helicobacter pylori, Metalloenzyme, Peptidoglycan, Zinc, Cell Shape, Meso-diaminopimelic Acid, Tripeptide

Abstract

Peptidoglycan modifying carboxypeptidases (CPs) are important determinants of bacterial cell shape. Here, we report crystal structures of Csd4, a three-domain protein from the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. The catalytic zinc in Csd4 is coordinated by a rare His-Glu-Gln configuration that is conserved among most Csd4 homologs, which form a distinct subfamily of CPs. Substitution of the glutamine to histidine, the residue found in prototypical zinc carboxypeptidases, resulted in decreased enzyme activity and inhibition by phosphate. Expression of the histidine variant at the native locus in a H. pylori csd4 deletion strain did not restore the wild-type helical morphology. Biochemical assays show that Csd4 can cleave a tripeptide peptidoglycan substrate analog to release m-DAP. Structures of Csd4 with this substrate analog or product bound at the active site reveal determinants of peptidoglycan specificity and the mechanism to cleave an isopeptide bond to release m-DAP. Our data suggest that Csd4 is the archetype of a new CP subfamily with a domain scheme that differs from this large family of peptide-cleaving enzymes.

Introduction

The peptidoglycan (PG)3 sacculus encases the cell and is responsible for maintaining cellular shape and protecting against osmotic stress in most bacteria (1). PG is a heteropolymer of glycan chains with attached short peptides that are cross-linked to form a rigid, mesh-like structure that retains cell shape when purified (2). This PG layer undergoes constant remodeling during cell growth, requiring enzymes that cleave (PG hydrolases) and grow (PG synthases) the existing PG structure. The combined effect of PG-modifying enzymes leads to diverse cellular morphologies, such as stars, squares, and spirals (3). However, much of our understanding of cell shape determination involves well studied organisms that are cocci, rods, or vibrioids, and we are only beginning to identify and understand the components involved in determining other bacterial cell shapes.

The PG glycan chains consist of alternating β-(1–4) linked GlcNAc and N-acetylmuramic acid. The peptide component varies in sequence depending on the species, especially for Gram(+) bacteria (4). In most Gram(−) and some Gram(+) species, the PG precursor is composed of the pentapeptide l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-m-DAP-d-Ala-d-Ala covalently linked to the N-acetylmuramic acid moiety (where m-DAP is meso-1,6-diaminopimelate) (1). Once attached to the nascent PG, the pentapeptide can be trimmed sequentially to a tetra-, tri-, and dipeptide by dd-, ld-, and dl-carboxypeptidases, respectively. The m-DAP and d-Ala residues from two opposing peptide stems can be directly cross-linked by dd-transpeptidases with the subsequent removal of a terminal d-Ala to form an A1γ-type linkage according to the classification scheme of Schleifer and Kandler (4).

Different classes of enzymes modify the intact peptidoglycan layer (5, 6). Periplasmic dd-carboxypeptidases are well characterized in many organisms and include both the penicillin-binding protein family and unrelated β-lactam-insensitive enzymes (7). Much less is known about enzymes that have dl-carboxypeptidase (dl-CP) activity. Recently, we have identified dl-CP genes required for helical shape in the Gram(−) pathogens Helicobacter pylori and Campylobacter jejuni (8–10). H. pylori is a specialized Gram(−) human pathogen of the ϵ class of proteobacteria that colonizes the epithelial surface of the gastric mucous layer and is the causative agent of gastric ulcers and gastric cancer (11). Deletion of H. pylori csd4 led to the loss of helical shape, resulting in slightly curved or straight rods that were impaired in murine stomach colonization assays (8). A similar study in C. jejuni, a closely related human diarrheal pathogen, revealed that deletion of the csd4 homolog, pgp1, led to a similar straight rod phenotype with impaired chick colonization ability, a model representing the natural reservoir of this pathogen (9). HPLC analysis of H. pylori Δcsd4 PG sacculi or purified disaccharide-linked tripeptide digested with Csd4 demonstrated production of a disaccharide dipeptide (i.e. dl-carboxypeptidase activity) (8).

Sequence analysis suggests that H. pylori Csd4 contains an N-terminal zinc-containing carboxypeptidase domain of the M14 family and a C-terminal region with unpredicted structural features. Zinc hydrolases have been grouped into over 30 families by Rawlings et al. (12). Family M14 consists of the carboxypeptidases, with the prototypical member being carboxypeptidase A (13). One hallmark feature of this family is the zinc-binding motif HXXE+H (+H2O). Zinc coordination lowers the pKa of the bound catalytic water (14). A second glutamate residue forms a H-bond to the catalytic water molecule and is proposed to abstract a proton forming a hydroxide ion that undergoes a nucleophilic attack on the bound substrate (15).

In this study, we show that Csd4 is a dl-carboxypeptidase with a modified zinc binding site containing a glutamine residue in place of a conserved histidine. To elucidate the hydrolytic mechanism, we have solved crystal structures of Csd4 with bound peptide substrate or product. Crystallographic studies, biochemical assays, and bacterial morphological studies of mutant strains implicate a key role of the glutamine ligand of the active site zinc ion in the formation of helical cell shape. Based on sequence analysis of Csd4 homologs, we propose that Csd4 is the archetype of a new CP subfamily.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Strains used in this work, as well as primers and plasmids used in strain construction are described in Table 1. H. pylori were grown in Brucella broth with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) without antimicrobials or on horse blood agar plates with antimicrobials as described (2). Bacteria were incubated at 37 °C under microaerobic conditions in a trigas incubator (10% CO2, 10% O2, and 80% air). For resistance marker selection, horse blood plates were supplemented with 15 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol, 25 μg ml−1 kanamycin, or 60 mg ml−1 sucrose. For plasmid selection and maintenance in Escherichia coli, cultures were routinely grown in LB broth or agar at 37 °C supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids, strains, and primers used in this study

| Relevant or descriptive genotype or description | Source or sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pLKS2 | Csd4 in pBluescript II SK+ | Ref. 8 |

| pLC292 | pRdxA with ampicillin resistance marker | Ref. 8 |

| pKB20 | Csd4 WT:3x-Flag (in pBluescript II SK+) | This work |

| pKB27 | Csd4 1–251:3x-Flag (in pBluescript II SK+) | This work |

| pKB29 | Csd4 1–343:3x-Flag (in pBluescript II SK+) | This work |

| pKB37 | Csd4 Q46A:3x-Flag (in pBluescript II SK+) | This work |

| pKB38 | Csd4 Q46H:3x-Flag (in pBluescript II SK+) | This work |

| pKB44 | rdxA::Csd4 WT:3x-Flag (in pLC292) | This work |

| pKB46 | rdxA::Csd4 Q46H:3x-Flag (in pLC292) | This work |

| pAC-C4H | Csd4 Q46H (in pET15) | This work |

| pAC-C4E | Csd4 Q46E (in pET15) | This work |

| pAC-C4A | Csd4 Q46A (in pET15) | This work |

| Strains | ||

| LSH100 | Wild-type H. pylori (G27 background) | Ref. 8 |

| LSH18 | csd4::catsacB | Ref. 8 |

| LSH108 | rdxA::kansacB | Ref. 2 |

| LSH122 | csd4::cat | Ref. 8 |

| TRH1 | Csd4 4x-Flag (at native locus) | This work |

| KBH19 | Csd4 WT:3x-Flag (at native locus) | This work |

| KBH33 | Csd4 Q46H:3x-Flag (at native locus) | This work |

| KBH35 | Csd4 1–343:3x-Flag (at native locus) | This work |

| KBH37 | Csd4 1–251:3x-Flag (at native locus) | This work |

| KBH42 | Csd4 Q46A:3x-Flag (at native locus) | This work |

| KBH47 | Csd4 Q46H:3x-Flag, rdxA::kansacB | This work |

| KBH54 | csd4::cat, rdxA::kansacB | This work |

| KBH60 | Csd4 Q46H:3x-Flag, rdxA::Csd4 Q46H:3x-Flag | This work |

| KBH64 | Csd4 WT:3x-Flag, rdxA::kansacB | This work |

| KBH65 | Csd4 WT:3x-Flag, rdxA::Csd4 WT:3x-Flag | This work |

| KBH66 | Csd4 WT:3x-Flag, rdxA::Csd4 Q46H:3x-Flag | This work |

| Primers | ||

| 53 | Csd4FLAG_UP_F | cgggccccccctcgaatgatagaagcttgcaaagcgtctt |

| 54 | Csd4FLAG_UP_R | acttttcaatctatatcttacttgtcg |

| 55 | Csd4FLAG_DN_F | tatagattgaaaagtgaatgggtgaatcttgccaaaagat |

| 56 | Csd4FLAG_DN_R | cgggctgcaggaattaacatgcatagctccatcaggtttca |

| 94 | Csd4-Q46A-SDM | tgttgcttttagcagggattgcaggcgatgagcctggggggt |

| 95 | Csd4-Q46H-SDM | ttgcttttagcagggattcatggcgatgagcctggggggtt |

| 85 | Csd4–3xF_UP_KpnI_F | gaattgggtaccgggccccc |

| 86 | Csd4–1–251_3xF_DNR | ataatccttatcgtcatcgtctttataatcaaaagggatattgagttgattgagtaa |

| 88 | Csd4–1–343_3xF_DNR | ataatccttatcgtcatcgtctttataatcaggatcaaactctatgtaaaaaggc |

| 89 | Csd4–3xF_DN_F | gattataaagacgatgacgataaggattat |

| 90 | Csd4–3xFDNSacI_R | aagctggagctccaccgcggt |

| 120 | Csd4–3xFl-BamHI | aggagggatccattggttttaaaatcgcttgtttcaac |

| 121 | Csd4–3xFl-EcoRI | ctcctgaattcttctaatgtatggcatgactatcctt |

| A1 | Csd4-Q46H-For | gttgcttttagcagggattcatggcgatgagcc |

| A2 | Csd4-Q46H-Rev | ggctcatcgccatgaatccctgctaaaagcaac |

| A3 | Csd4-Q46E-For | ttgttgcttttagcagggattgaaggcgatgagc |

| A4 | Csd4-Q46E-Rev | gctcatcgccttcaatccctgctaaaagcaacaa |

| A5 | Csd4-Q46A-For | aggctcatcgcctgcaatccctgctaaaagcaacaaatgg |

| A6 | Csd4-Q46A-Rev | ccatttgttgcttttagcagggattgcaggcgatgagcct |

Synthesis of Tripeptide Substrate

Chemicals were purchased from Aldrich, Alfa Aesar, or Fisher Scientific. Ion exchange resin was from Aldrich and Bio-Rad. Silica gel (230–400 mesh) was obtained from Silicycle Inc. The TLC silica gel (aluminum sheets) was from EMD Chemical Inc. CH2Cl2, MeOH, and TEA were distilled under argon from CaH2. 1H NMR and proton-decoupled 31P NMR were recorded on a Bruker AV400dir spectrometer or a Bruker AV400inv spectrometer at field strength of 400 and 162 MHz, respectively. Mass spectra were obtained on a Waters 2965 HPLC-MS.

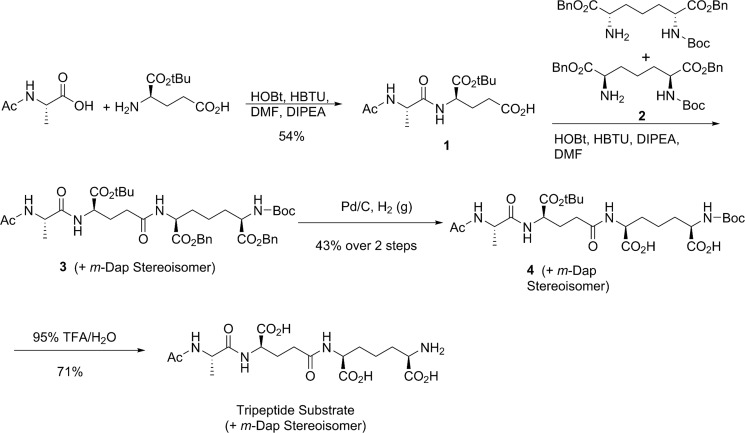

Ac-l-Ala-d-Glu(OtBu)-OH (Compound 1)

To a solution of N-acetyl-l-alanine (131 mg, 1.0 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (10 ml) was added hydroxybenzotriazole (135 mg, 1.0 mmol) and HBTU (380 mg, 1.0 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. d-Glu(OtBu)-OH (203 mg, 1.0 mmol) and di-isopropyl ethylamine (0.15 ml, 1.0 mmol) were added, and the reaction was stirred for another 2 h at room temperature (Fig. 1). The solution was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure and was extracted with H2O/ethyl acetate. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel (4% MeOH in CH2Cl2) to give compound 1 as a colorless oil (256 mg, 54%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.46–4.25 (m, 2H), 2.52–2.30 (m, 2H), 2.23–2.10 (m, 1H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.96–1.87 (m, 1H), 1.48 (s, 9H), 1.35 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); MS (ESI) (m/z) 339.4 [M+Na]+.

FIGURE 1.

The synthetic scheme for the tripeptide substrate.

Compound 3

To a solution of Ac-l-Ala-d-Glu(OtBu)-OH (Compound 1, 72 mg, 0.23 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (5 ml) was added hydroxybenzotriazole (34 mg, 0.25 mmol) and HBTU (96 mg, 0.25 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. Mono-Boc-protected meso-Dap dibenzyl ester (compound 2, 98 mg, 0.21 mmol) and di-isopropyl ethylamine (27 mg, 0.21 mmol) were added, the reaction was stirred for another 2 h at room temperature. Compound 2 was prepared as a mixture of two regioisomers according to a literature known method (16). The solution was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure and was extracted with H2O/ethyl acetate. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel (4% MeOH in CH2Cl2), but the 1H NMR spectrum showed that the fraction containing compound 3 still included significant amount of impurities. Therefore, the impure compound 3 fraction was used for the next step without further purification: MS (ESI) (m/z) 791.5 [M+Na]+.

Compound 4

To a solution of compound 3 (70 mg, 0.91 mmol) in MeOH (20 ml) was added Pd/C (10%, 50 mg). The resulting mixture was stirred under hydrogen gas (1 atm) for 5 h and then filtered through celite. The filtrate was evaporated in vacuo and dried under reduced pressure to give compound 4 as a colorless oil. The crude oil was dissolved in NaHCO3 solution (10%), and the pH was adjusted to 8.0. This was loaded onto a column of AG 1-X8 resin (formate form, 100–200 mesh, 5 ml). The column was washed with water (50 ml) and formic acid (0.5 m, 100 ml). The fractions containing the product were combined and evaporated to dryness in vacuo to give compound 4 (mixture of two diastereoisomers) as a colorless oil (55 mg, 43% over two steps): 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.41–4.32 (m, 2H), 4.30–4.18 (m, 2H), 2.71 (m, 2H), 2.38–2.30 (m, 2H), 2.02 (s, 3H), 1.90–1.84 (m, 4H), 1.78–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.48 (s, 9H), 1.45 (s, 9H), 1.40–1.35 (m, 3H); MS (ESI) (m/z) 611.3 [M+Na]+.

Ac-l-Ala-iso-d-Glu(OH)-meso-Dap-OH (Tripeptide Substrate)

Compound 4 (55 mg, 0.91 mmol) was dissolved in TFA (9.5 ml)/H2O (0.5 ml). The resulting solution was stirred for 3 h at room temperature and then was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was redissolved in H2O (2.0 ml), and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 8 by adding NaHCO3 (0.5 m). This was loaded onto a column of AG 1-X8 resin (formate form, 100–200 mesh, 5 ml). The column was washed with water (50 ml) and formic acid (0.5 m, 50 ml) and then was eluted by formic acid (4.0 m, 100 ml). The fractions containing the compound were combined and evaporated to dryness in vacuo to give the tripeptide substrate (mixture of two diastereoisomers) as a colorless oil (28 mg, 71%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.40 (m, 3H), 4.12–3.94 (m, 1H), 2.49–2.28 (m, 3H), 2.27–2.16 (m, 1H), 2.08–2.03 (m, 2H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.99–1.86 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.72 (m, 1H), 1.67–1.52 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.35 (m, 3H); MS (ESI) (m/z) 433.4 [M+H]+.

Cloning and Recombinant Expression of Csd4

Wild-type Csd4, consisting of the native H. pylori strain G27 sequence (HPG27_353) minus the first 20 N-terminal signal sequence residues, three Csd4 active-site variants (Q46H, Q46A, and Q46E) and Corynebacterium glutamicum meso-diaminopimelate dehydrogenase (DAPDH) were used in this study. Cloning of csd4 into pET15 vector for recombinant expression has been described previously (8). Gln-46 variants were made in pET15-csd4 using the Agilent QuikChange XL kit with primers A1–A6 described in Table 1 and verified by sequencing. All Csd4 variants were overexpressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3). Each 1-liter culture was inoculated with 2 ml of overnight culture and incubated at 37 °C with shaking. When the cell density reached an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.9, the temperature was reduced to 20 °C for 30 min and then induced with 0.25 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and grown overnight. The cells were pelleted, resuspended, and lysed at 4 °C in binding buffer (25 mm NaH2PO4, pH 8, 600 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 5 mm imidazole) with an Emulsi Flex-C5 homogenizer (Avestin). The soluble fraction was loaded onto a ProBond nickel resin affinity column (Invitrogen), and the protein was eluted with increasing imidazole in binding buffer at pH 7.5. Csd4 was then dialyzed into 25 mm NaH2PO4, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, and digested with thrombin overnight (500:1 w/w Csd4:thrombin ratio) at 4 °C to remove the His tag. Benzamidine beads were used to remove the thrombin, and the protein was further purified by gel filtration chromatography (Superdex 200 16/60 column) equilibrated with 20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl. Q46H Csd4 used for crystallization was not additionally purified by gel filtration but was buffer exchanged by ultrafiltration. The protein concentration was calculated using an extinction coefficient value of 36,190 m−1 cm−1 for folded Csd4 protein (ϵfolded). ϵfolded was derived using the Beer-Lambert law and UV absorption values of Csd4 denatured in 6 m guanidium hydrochloride and predicted extinction coefficient values (ϵunfolded) (17). Protein samples were then concentrated to ∼15–20 mg ml−1 and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Recombinant DAPDH protein was expressed and purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) (vector was a generous gift from Lilian Hor and Matthew Perugini, La Trobe University, Australia) as previously described (18).

Construction of H. pylori Strains Expressing Tagged and Mutant Csd4

Plasmids containing wild-type and mutant derivatives of csd4 fused to the 3x-Flag epitope were used for complementation and creation of merodiploid strains and are described in Table 1. To generate pKB20, the csd4 gene and the 3x-flag epitope were individually amplified by PCR (Phusion, NEB) using TRH1 (csd4:4xFLAG) genomic DNA as template, with oligonucleotides 53/54 (csd4) and 55/56 (3x-Flag), which contained XhoI and EcoRI sequences appended. Strain TRH1 was generated using PCR SOEing (19) to add the 3x-FLAG sequences and a stop codon right before the endogenous csd4 stop codon, which was then used to replace csd4::catsacB in LSH18 using counterselection (8, 20, 21). The vector pLKS2 (8) was digested with XhoI and EcoRI (NEB) and gel-purified (Qiagen). The vector backbone and purified PCR fragments were ligated together using the HD In-Fusion cloning kit (Clontech). Point mutant derivatives of csd4 were generated using a modified quick change procedure (Stratagene) with the pKB20 master vector as template and oligonucleotides 94 (Q46A) and 95(Q46H). To generate pKB27 and pKB29, the csd4 truncation alleles and the 3x-Flag epitope were individually amplified using pKB20 as template with primers 85/86 (Csd41–251), 85/87 (Csd41–343), and 89/90 (3x-Flag). The csd4 alleles and 3x-flag were gel-purified and stitched together by PCR SOEing (19) using primers 85/90, which contained KpnI and SacI sequences appended. The vector pKB20 and the stitched PCR products were digested with KpnI and SacI and gel-purified. The vector backbone and PCR fragments were ligated together using standard T4 ligase-based methodology and verified by Sanger sequencing of candidate clones (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Genomics Shared Resource). To generate pKB44 and pKB46 for integration of mutant alleles at the rdxA locus, the csd4–3x-Flag alleles were PCR-amplified from KBH33 (Csd4 Q46H:3x-Flag) and KBH42 (Csd4 Q46A:3x-Flag) genomic DNA using primers 120/121 with BamHI and EcoRI sequences appended, digested with BamHI and EcoRI, and gel-purified. The vector pLC292 (22) was digested with BamHI and EcoRI (NEB) and gel-purified (Qiagen). The vector backbone and purified PCR fragments were ligated together using standard T4 ligase-based methodology and verified by Sanger sequencing of candidate clones (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Genomics Shared Resource). Recipient H. pylori bacteria containing a csd4::catsacB (LSH18) or rdxA::kansacB (LSH108) cassette (LSH18) were transformed with 2–4 μg of the appropriate plasmid DNA (Qiagen) containing DNA sequences homologous to regions flanking the rdxA::kansacB or csd4::catsacB cassette. Genomic DNA was isolated from candidate clones and verified by Sanger sequencing of PCR-amplified csd4 (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Genomics Shared Resource).

Crystallization and Structure Determination

Initial phasing by molecular replacement using available structures of distantly related carboxypeptidases did not lead to interpretable maps. Instead, a crystallization condition containing iodide was optimized to employ de novo phasing. The final structures of wild-type Csd4 and its variants were crystallized in the P212121 space group using reservoir solution containing 16–20% PEG 3350, 0–100 μm Tris, pH 8, and 0.3–0.4 m sodium iodide by hanging drop vapor diffusion. Crystals appear within a few days at room temperature but were allowed to grow to a sufficient size for ∼2 weeks. The crystal structure was initially determined to 2.1 Å by single wavelength iodide phasing using data collected at the UBC Astrid x-ray home source (1.54 Å wavelength) at 100 K. The data were processed and phased using HKL3000 (23) (Csd4-initial in Table 2). The anomalous substructure determined by SHELXD (24) contained 14 iodide sites. A combination of autobuilding with ArpWarp (25) and manual rebuilding using Coot (26) were used to complete the structure, which included the manual placement of additional iodide sites. Zinc-containing crystal structures of WT and Q46H Csd4 were obtained by sequentially soaking the crystals in freshly prepared 3% increments of PEG 3350 (all other concentrations remaining the same as the reservoir; ∼5 min per step) up to 27% followed by the addition of an equal volume of 27% soaking solution supplemented with 4 mm ZnCl2 for 30 and 60 min, respectively. These crystals were then soaked in 27% soaking solution with ethylene glycol as a cryoprotectant (25% (v/v)). Similarly, the tripeptide containing crystals were prepared by sequential soaking up to 33% PEG 3350, but with each soaking solution also supplemented with 1 mm ZnCl2, followed by a 30-min soak in the 33% solution supplemented with 2.5 mm tripeptide and 1 mm ZnCl2. An equal volume of 33% soaking solution supplemented with 4 mm ZnCl2 was then added and soaked for another 9 min, followed by a quick soak in the same cryoprotectant and flash frozen. Native (0.98–1.00 Å) and zinc anomalous (1.26–1.28 Å) wavelength data sets on derivatized crystals were collected at the Canadian Lightsource Beamlines 08B1-1 and 08ID-1 at 100 K and processed using XDS (27). The original Csd4 structure was then used as a starting point for direct refinement using PHENIX and manual rebuilding with Coot. Poor electron density precluded modeling of the following loop region on domain 3: residues 389–394 (TriZn-Csd4); residues 389–392 with Lys-393 modeled as Ala (Q46H-Csd4 and Zn-Csd4). All structures have excellent stereochemistry, with 96.9–97.4% of residues in the favored region of the Ramachandran plots and no outliers. The atomic coordinates for the crystal structures of Apo-Csd4, Zn-Csd4, TriZn-Csd4, and Q46H-Csd4 are available in the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank under codes 4WCK, 4WCL, 4WCN, and 4WCM, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for Csd4

| Apo-Csd4 | Zn-Csd4 | TriZn-Csd4 | Q46H-Csd4 | Csd4 initial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 53.28, 66.78, 145.53 | 53.02, 66.77, 144.56 | 53.23, 66.83, 145.05 | 53.60 66.65 145.40 | 53.11 66.92 146.02 |

| Resolution (Å) | 42.99-1.40 (1.45-1.40) | 42.76-1.85 (1.92-1.85) | 49.15-1.75 (1.81-1.75) | 49.13-1.75 (1.81-1.75) | 50.00-2.10 (2.14-2.10) |

| Rmerge | 0.070 (0.644) | 0.062 (0.434) | 0.058 (0.539) | 0.078 (0.463) | 0.148 (0.469) |

| I/σI | 17.5 (3.6) | 21.4 (4.6) | 21.2 (2.8) | 15.4 (3.0) | 21.2 (2.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (99.9) | 99.8 (99.3) | 99.6 (96.3) | 99.8 (97.9) | 99.9 (98.3) |

| Redundancy | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 27.4 |

| Refinement | |||||

| No. unique reflections | 102,944 | 44,613 | 52,911 | 53,300 | 31,191 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.14/0.16 | 0.17/0.20 | 0.18/0.21 | 0.18/0.21 | 0.17/0.22 |

| No. atoms | |||||

| Protein | 7002 | 6803 | 6803 | 6823 | 3428 |

| Substrate/product | 25 | 25 | 55 | 25 | 13 |

| Water | 466 | 401 | 327 | 451 | 384 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||||

| Protein | 23.1 | 28.6 | 30.0 | 25.0 | 17.6 |

| Substrate/product | 19.9 | 21.1 | 44.9 | 35.1 | 14.5 |

| Water | 35.1 | 35.2 | 37.2 | 34.5 | 26.0 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.49 | 1.09 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 1.41 |

| PDB accession code | 4WCK | 4WCL | 4WCN | 4WCM | |

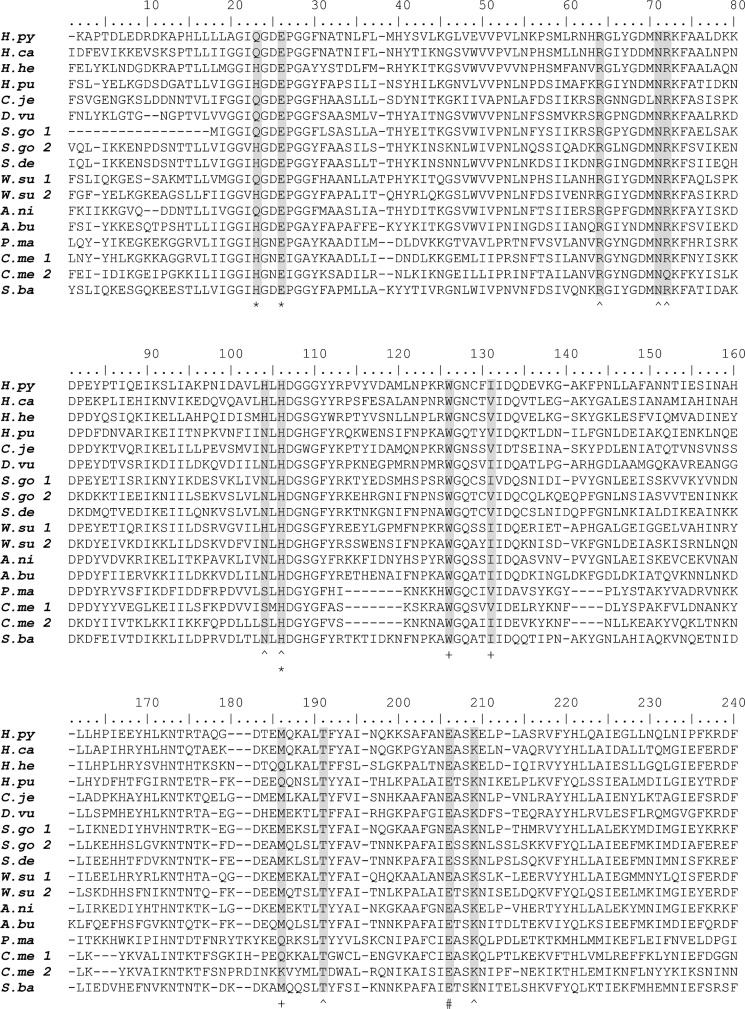

Sequence Alignments

Homologs of Csd4 were identified from the nonredundant database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information utilizing BLASTP and an E value cutoff of 1 × 10−7. Identical protein sequences derived from different strains of the same species and proteins with short alignment coverage were removed. The sequences were aligned with Clustal Omega (28), and a bootstrapped tree (with 500 replicates, subtree pruning and regrafting, and five random starts) was generated using PhyML (29) within Seaview (30). The aligned sequences were also used to generate Fig. 2C using Consurf (31) to identify the degree of amino acid conservation.

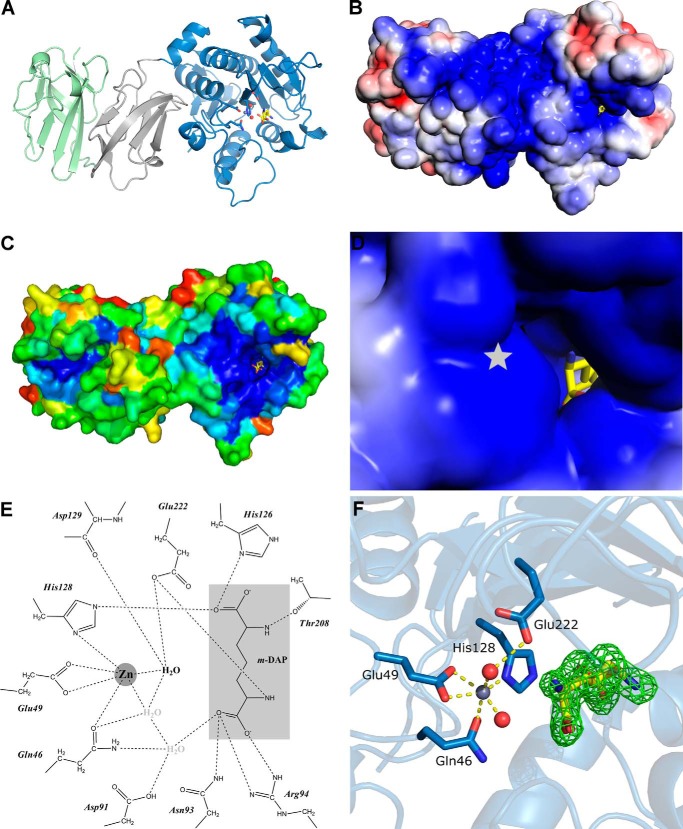

FIGURE 2.

The crystal structure of Csd4 (PDB code 4WCL). A, the overall monomeric structure of Csd4 with Zn2+ and m-DAP bound. The catalytic domain and domains 2 and 3 are colored blue, gray, and green, respectively. B and D, overall (B) and active site (D) magnified electrostatic surface potential of Csd4 contoured at ±3 kbT/ec. Electropositive regions are colored blue; electronegative regions are colored red; position of buried Zn2+ indicated with a star. C, distribution of conserved residues mapped onto the surface of Csd4. Most conserved regions are colored blue; the least conserved is colored red. E, two-dimensional interaction map between Csd4 and the product m-DAP (light gray). The predicted catalytic water highlighted in bold type. F, corresponding Zn-Csd4 active site with key ligands and an omit Fo − Fc difference density map for the density of the bound m-DAP product contoured at 3 σ.

UV-visible Spectroscopy

C. glutamicum DAPDH was used to determine the cleavage rates by Csd4 and its variants by consuming the predicted product of the Csd4 reaction, m-DAP, and NADP+. The consumption of NADP+ to produce NADPH is detectable as an increase in absorbance at 340 nm. To determine the activity profile of DAPDH over various pH values, various concentrations of DAPDH was incubated with 100 mm buffer (Bis-tris, pH 5.6 and 6.5; MES, pH 6; and Tris, pH 7.5 and 8), 500 mm NaCl, 0.3 mm NADP+, and 1.2 mm m-DAP. Because of differing DAPDH activity at varying pH levels, an uncoupled assay was used to examine the pH effects on Csd4 activity. 5 μm Csd4 was incubated in 20 mm sodium/potassium phosphate (pH 4.8, 5, 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, and 8), 500 mm NaCl, and 7 μm EDTA for 5 min at 30 °C, followed by the addition of 17 μm ZnCl2 and incubating for another 5 min. The reaction was then initiated by the addition of 1 mm tripeptide, incubated for 20 min, and stopped by boiling the sample for 10 min at 98 °C. The sample was then centrifuged to remove precipitated protein, mixed with Tris, pH 8 (final concentration, 100 mm), 2.5 mm NADP+, and 2.5 μm DAPDH, and the relative activity was determined based on final absorption values at 340 nm. Assays that coupled the reactions of Csd4 and DAPDH involved 100 mm buffer (sodium/potassium phosphate or Bis-tris, pH 6.5), 0.5 mm NaCl, 0.25 mm ZnCl2, 2.5 mm NADP+, 25 μm DAPDH, and 5 μm Csd4. After 10 min of incubation at 30 °C, the reaction was initiated by adding 1 mm peptide substrate. An initial lag phase is observed caused by the coupling of detection by DAPDH consumption of NADP+ to the production of m-DAP by Csd4. Reaction rates were calculated using the maximal slope of the change in A340 nm and the molar absorptivity ϵ340 values.

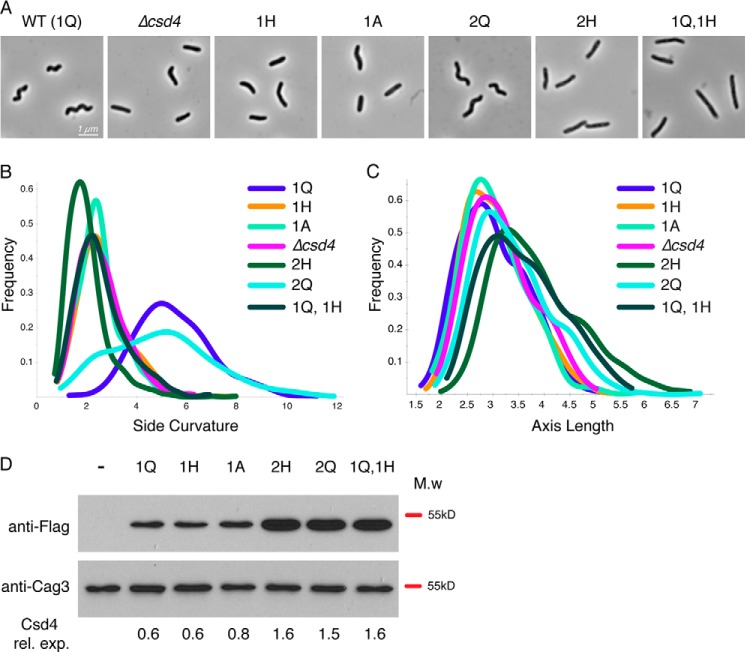

H. pylori Morphological Analyses

Phase contrast microscopy was performed as described (2), and resulting images were thresholded using the ImageJ software package. Quantitative analysis of threshold images of bacteria (300–350 cells/strain) to measure side curvature and central axis length was performed with the CellTool software package as described (2). Side curvature is the reciprocal of the radius of a circle tangent to a curve at any point; as such, a straight line has zero curvature, whereas a point on a bent line has a curvature proportional to the tightness of the bend. Cell length was estimated using the central axis length calculated by CellTool. Statistical comparison of cell shape distributions were performed using a CellTool module that calculates a bootstrap distribution of Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics, as described (8).

Immunoblotting

H. pylori whole cell extracts were prepared by harvesting log phase grown bacteria by centrifugation for 2 min at maximum speed in a microcentrifuge and resuspending in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer at 10.0 optical density (600 nm) per ml and boiled for 10 min. Proteins were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes using a semidry transfer system (I-blot; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C with 5% nonfat milk-Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS-T; 0.5 m Tris, 1.5 m NaCl, pH 7.6, plus 0.05% Tween 20), followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody at 1:2500 dilution for anti-Flag M2 (Sigma) or 1:20,000 dilution for anti-Cag3, in TBS-T (10). Four 10-min washes with TBS-T were followed by a 1-h incubation at room temperature with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody at 1:20,000 dilution in TBS-T (anti-rabbit for Cag3 blots, anti-mouse for 3x-Flag blots). After four more TBS-T washes, antibody detection was performed with ECL Plus immunoblotting (Cag3) or Millipore Immobilon (3x-Flag) detection kits, following the manufacturer's protocol (GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

Domain Structure of Csd4

The 1.40 Å resolution Csd4 crystal structure reveals a monomer with an N-terminal carboxypeptidase domain, followed by two smaller domains of unknown function (domains 2 and 3; Fig. 2A and Table 2). The CP domain, consisting of residues 1–251 of the native sequence, is globular with a mixed α/β fold containing a nine-stranded antiparallel β-sheet core sandwiched by groups of four and five α-helices. A structural similarity search using DaliLite (32) found significant similarity between the CP domain and the family of funnelin-type carboxypeptidases (e.g. human carboxypeptidase B2, PDB code 3LMS, Z score 19.1, r.m.s.d. 2.3 Å over 192 aligned residues), a family of metallopeptidases that exhibits CP activity (15). Although the overall funnelin fold was conserved, sequence identities with Csd4 are under 20% over the aligned regions. Domains 2 (residues 252–343) and 3 (residues 343–438) consist primarily of β-strands with one and two half-turn helices, respectively, in an immunoglobulin-like fold (Fig. 2A). Neither domain 2 nor 3 shares significant structural similarity with components found in other carboxypeptidases. Instead, domain 2 shares low structural similarity to a binding domain of human RhoGDI (PDB code 1HH4, Z score 3.2, r.m.s.d. 2.9 Å over 65 residues). Domain 3 shares some structural similarity to the periplasmic, non-sugar-bound domain of a heparin-sensing two component system (BT4663) of the human gut symbiont Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (PDB code 4A2M, Z score 4.9, r.m.s.d. 2.9 Å over 79 residues). Because of weak structural and sequence similarity, domains 2 and 3 are not likely to have similar functions as their top Dali hits. Instead, we predict that these domains participate in protein-protein or protein-PG interactions.

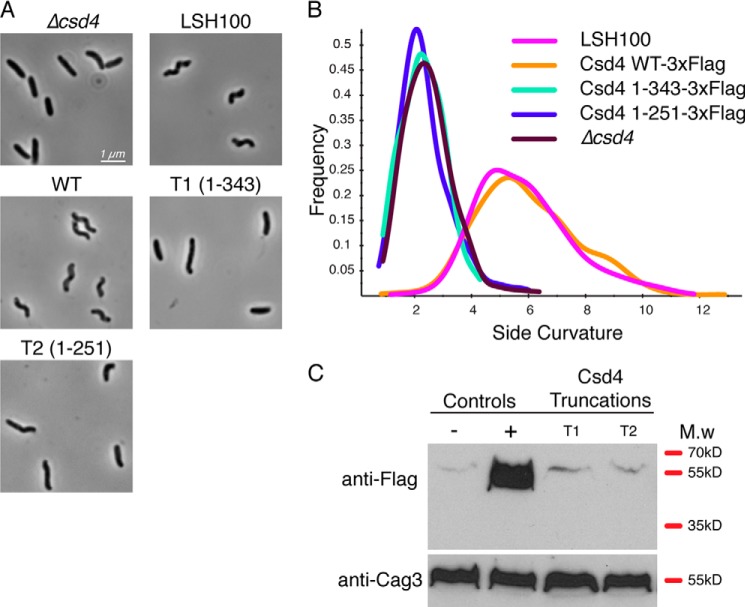

Domains 2 and 3 are required for stable Csd4 expression because replacement of the endogenous csd4 gene with a 3x-Flag-tagged allele truncated at the end of either domain 1 or 2 at the native locus resulted in no detectable expression within whole cell lysates (using an anti-Flag antibody) and showed a straight rod phenotype similar to the null allele (Fig. 3). In contrast, replacement with full-length Csd4 containing the same 3x-Flag epitope revealed the robust expression of the epitope-tagged full-length allele and showed normal morphology. From inspection of the crystal structures, the two domain interfaces (∼945 Å2 between domains 1 and 2; ∼820 Å2 between domains 2 and 3) are largely hydrophobic, suggesting that both domains are required to stabilize the protein within cells.

FIGURE 3.

Complementation and Western blot analysis of Csd4–3x-Flag control and Csd4 C-terminal truncations. The strains used were LSH18 (Δcsd4), LSH100 WT (no 3x-Flag tag), KBH19 (WT-3x-Flag), KBH35 (T1–3x-Flag), and KBH37 (T2–3x-Flag). A, 1000× phase contrast images of wild-type and mutant H. pylori. B, smooth histograms displaying population cell curvature (x axis) as a density function (y axis). C, Western blot analysis of Csd4 (detected by anti-Flag M2 antibody); LSH100 WT (−); KBH19 (+) with a predicted molecular mass of 48 kDa; KBH35 (T1) with a predicted molecular mass of 39 kDa; KBH37 (T2) with a predicted molecular mass of 28 kDa; and Cag3 with a predicted molecular mass of 55 kDa. Equivalent amounts of cell extract based on optical density of the culture were loaded for each strain.

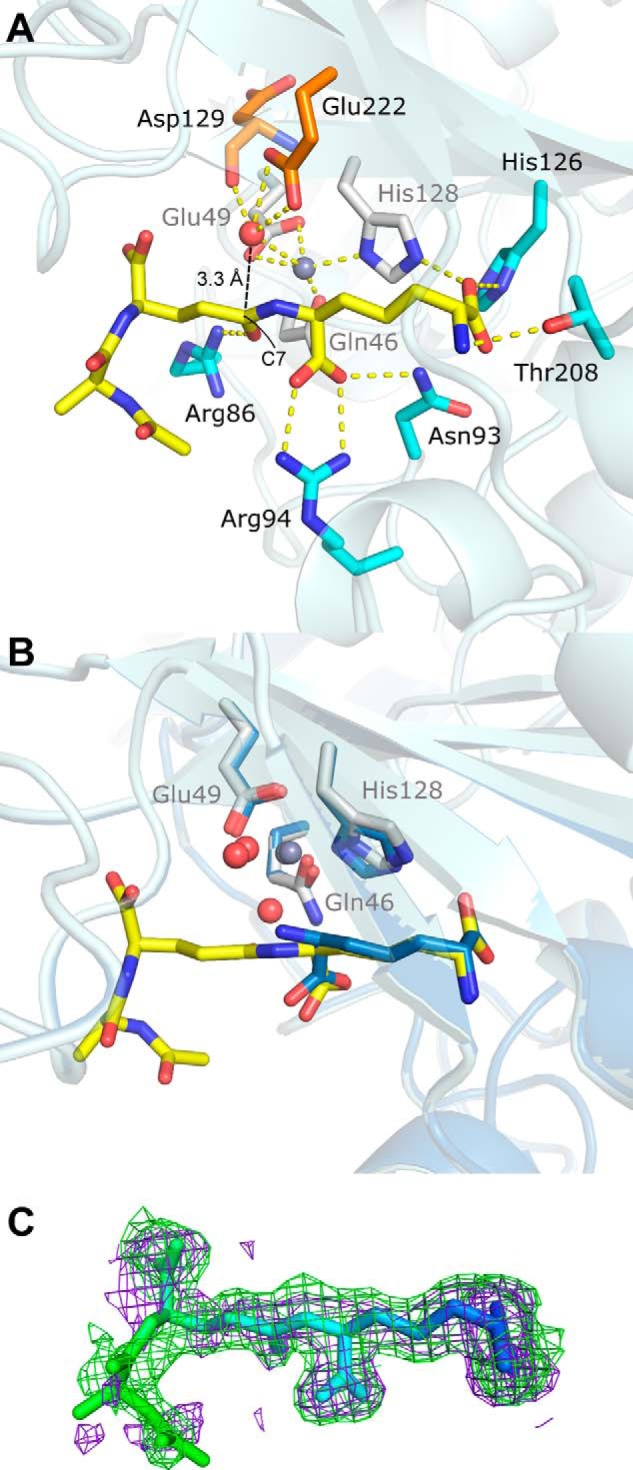

PG Peptide Binding to the Active Site of Csd4

In contrast to all other characterized members of the CP family, the catalytic zinc site of Csd4 consists of Glu, His, and an atypical Gln residue. Zn2+ was soaked into Csd4 crystals to obtain a structure with zinc bound at 90% occupancy (Zn-Csd4). The zinc site is situated along the inner edge of a shallow, positively charged substrate-binding pocket located on the surface of the CP domain (Fig. 2, B and D). The metal ion is coordinated by His-128 Nδ1 (2.0 Å), the side chain carboxylate of Glu-49 in a symmetric, bidentate manner (2.3/2.3 Å), and Gln-46 through the carboxamide Oϵ (2.2 Å) in Zn-Csd4 (Fig. 2, E and F). Two additional density peaks that are best modeled as either water or hydroxide ions (2.2 and 2.3 Å) are also observed (Table 2), together forming an infrequently observed six-coordinate zinc site (33).

The initial crystal structure of Csd4 (Csd4-initial) did not contain bound metal in the active site, as observed for other carboxypeptidases (34), suggesting weak affinity or insufficient metal availability during protein purification. Zinc binding results in structural changes to the active site ligands. His-128 exhibits an 18° rotation about Cβ to bring the imidazole ring closer to the zinc ion. In the absence of a bound metal, Gln-46 has elevated B-factors, and the carboxamide side chain is primarily directed away from the active site. Upon zinc binding, Gln-46 reorients toward the zinc ion, strongly supporting formation of a Gln-46-Zn2+ ligand interaction. No significant displacement of Glu-49 is observed.

In the substrate-binding pocket of Csd4-initial, apo-Csd4, and Zn-Csd4, positive electron density was observed matching the proposed tripeptide cleavage product, m-DAP, based on comparisons between wild-type and Δcsd4 PG from H. pylori (8). Because no exogenous m-DAP was included during the purification or crystallization of Csd4, affinity for m-DAP was sufficiently high for co-purification from E. coli lysate. The m-DAP forms direct interactions with Asn-93, Arg-94, His-126, the Zn2+ ligand His-128, Thr-208, and Glu-222 (Fig. 2, E and F). Asp-91 directly forms an H-bond to the Zn2+ ligand Gln-46 and to a water molecule that is H-bonded to both Gln-46 and the outer carboxylate oxygen of m-DAP. Three hydrophobic residues also line one side of the substrate-binding pocket (Trp-148, Ile-153, and Met-203) to interact with the alkyl portion of m-DAP. Additionally, a buried network of water molecules is present that form interactions between m-DAP and both Csd4 backbone and side chain residues.

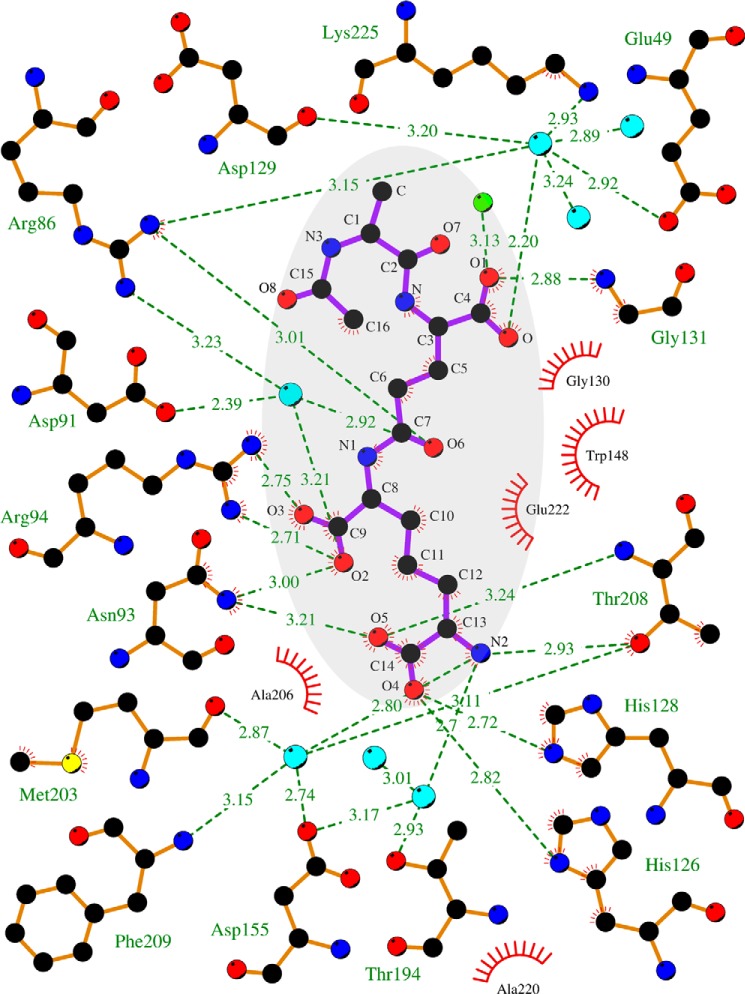

To examine the interactions of Csd4 with substrate, Csd4 crystal soaking experiments were performed with Zn2+ and a tripeptide representing a portion of the PG substrate (Ac-l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-m-DAP; Fig. 1). The substrate was synthesized as a mixture of two stereoisomers: one with the (R)-stereocenter of m-Dap attached to γ-d-Glu and one with the (S)-stereocenter of m-Dap attached to γ-d-Glu. The crystal structure of tripeptide-Zn2+-Csd4 complex (TriZn-Csd4) was solved to 1.75 Å (Tables 2 and 3). No significant difference in the overall fold was observed when compared with Zn-Csd4 (r.m.s.d. 0.2 Å over all Cα atoms). Electron density at the metal binding site was weaker, and a zinc ion was modeled at 50% occupancy. As in Zn-Csd4, Gln-46, His-128, and Glu-49 are coordinated to the zinc ion; additionally, a single solvent molecule with well defined electron density is observed coordinated to the zinc and is modeled as a water at full occupancy (Table 3 and Fig. 4A). This water is H-bonded to the backbone carbonyl group of Asp-129 (2.8 Å) and the side chain of Glu-222 (2.9 and 3.1 Å, bidentate) and is situated 3.3 Å from C7 of the tripeptide scissile bond. Therefore, it is poised to be the catalytically essential water (15), although conformational changes at the active site may be required during the catalytic process. The second zinc coordinated water molecule in Zn-Csd4 appears to have been displaced by the bound tripeptide.

TABLE 3.

Zinc ligand bond lengths in the crystal structures of Csd4

| Zn-Csd4 | TriZn-Csd4 | Q46H-Csd4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gln-46/His-46 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| Glu-49 | 2.3/2.3 | 2.4/2.6 | 2.1/2.5 |

| His-128 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.1 |

| H2O (catalytic) | 2.3 | 2.9 | |

| H2O (other) | 2.2 | ||

| Phosphate | 1.9 |

FIGURE 4.

Tripeptide substrate binding site (PDB code 4WCN). A, key zinc and substrate interactions with Csd4 are shown. Zinc ligands are colored white; tripeptide ligands are colored cyan; the predicted catalytic water is red, and its ligands are orange; zinc is gray; and key interactions are shown as dotted lines. Hydrophobic residues and other waters are not shown. B, structural alignment between substrate- and product-bound Csd4. The view is of the active site in A with a 30° rotation about the x axis. C, tripeptide omit Fo − Fc difference map contoured at 2 σ generated prior to the addition of the tripeptide to the model (purple) and from the final model (green) showing well defined omit density for the deeply buried portions of the tripeptide substrate. Increased tripeptide flexibility in relation to the degree of surface exposure are indicated by a B-factor based coloring scheme (blue = ∼20 Å2 and green = ∼60 Å2).

The tripeptide substrate analog was modeled at full occupancy in TriZn-Csd4 (Fig. 4). Under the crystal soaking conditions, tripeptide cleavage is sufficiently impaired that the substrate and not the product was observed. Only the naturally occurring stereoisomer (the (S)-stereocenter of m-Dap attached to γ-d-Glu) was observed in the active site, indicating that the enzyme selectively bound the preferred isomer from solution. The m-DAP moiety of the tripeptide overlays with the product structure, and the interactions with Csd4 are conserved (Fig. 4B). The tripeptide substrate extends outward past the binding pocket, and only the carbonyl O of d-Glu provides an additional significant interaction with Arg-86 (Figs. 4A and 5). Accordingly, the B-factors of the buried m-DAP moiety are low (∼20 Å2) and increase toward the surface-exposed end of the tripeptide (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 5.

Two-dimensional tripeptide-Csd4 interaction map (PDB code 4WCN). Tripeptide substrate is highlighted in gray; waters are colored cyan; iodide is in green; red bristled arcs depict nearby hydrophobic interactions; and zinc cofactor and its ligands are not shown. The figure was drawn using LigPlot+ (43).

Plotting the degree of amino acid conservation among the homologs of Csd4 (see below) on the surface of the structure reveals highest conservation at the substrate binding site (Fig. 2C). Although the majority of these conserved residues are part of the extensive zinc and substrate binding network, additional conserved residues are present at the CP domain surface surrounding the active site pocket. This surface is composed primarily of loops, the largest of which consists of residues Tyr-133–Trp-148 that are poised to interact with the polysaccharide backbone of the PG substrate.

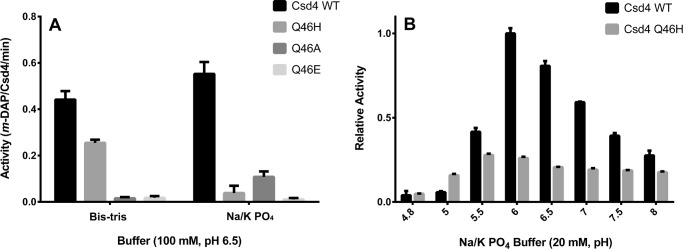

Gln-46 Is Required for Full Csd4 Activity

To examine the role of Gln-46 in the catalytic activity of Csd4, three active site variants were constructed (Q46H, Q46A, and Q46E) and assayed for m-DAP release from the tripeptide substrate. Wild-type Csd4 demonstrated highest activity in either sodium/potassium phosphate or Bis-tris buffer (Fig. 6A). The peptidase activity of the Q46H variant was half that of wild type in the Bis-tris-buffered system but was 10-fold reduced in the presence of phosphate. The complete loss of a zinc ligand (Q46A variant) retained ∼20% of wild-type activity in phosphate but no significant activity in Bis-tris buffer. Substitution of Gln with acidic Glu resulted in no significant activity and appeared to disrupt the active site. Wild-type Csd4 had highest activity at pH 6, whereas the Q46H optimal was at pH 5.5 but was much less pH-sensitive (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Wild-type Csd4 exhibits higher catalytic activity on the tripeptide substrate than its active site variants. A, Csd4 activity was continuously monitored via the activity of meso-diaminopimelate dehydrogenase, which consumes the Csd4 product m-DAP to produce NADPH. Buffer-based activity rate differences of Csd4 and its variants are shown. B, the pH-based activity differences between wild-type Csd4 and the Q46H variant was examined by examining the amount of product produced after 20 min. Mean values are shown with error bars representing the standard deviation based on at least three experimental replicates. The p value for all variants is <0.0005 as compared with wild type in their respective buffers utilizing the t test in A. p values between wild type and Q46H are <0.0006 for all pH values except pH 4.8 in B.

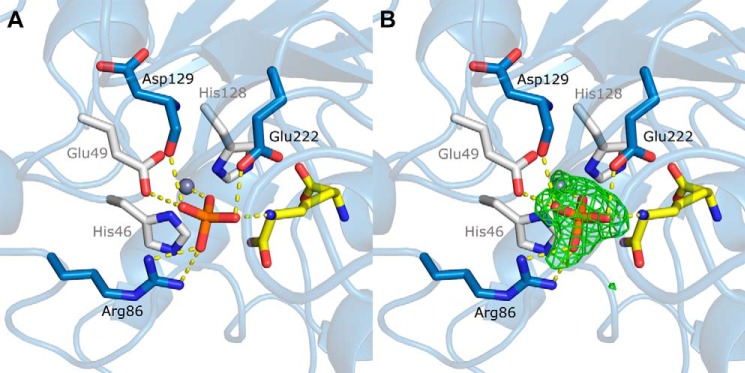

To explore the structural basis for altered activity by the Q46H variant, the crystal structure of zinc-bound Q46H was solved to 1.75 Å resolution (Fig. 7A). As expected, the His-His-Glu metal site bound Zn2+ with modest changes in ligand geometry (Table 3). A tetragonal-shaped density was observed near the zinc ion in a Fo - Fc map (Fig. 7B). Based on the presence of phosphate in the protein purification buffer, the density was modeled as a phosphate molecule at 90% occupancy. Structural alignment between TriZn-Csd4 and the Q46H variant revealed that the phosphate molecule occupies the space of the zinc-coordinated solvent molecule. Arg-86 and Glu-222 have rotated to form H-bonds with the phosphate group. Density for the product, m-DAP, is observed in the structure of Q46H and is situated in the same location as in the wild-type Csd4 structures.

FIGURE 7.

Active site of the zinc-bound Q46H variant (PDB code 4WCM). A, zinc ligands are colored white; m-DAP is in yellow; phosphate is in orange; other residues interacting with the phosphate are colored blue; and phosphate interactions are shown as dotted lines. B, omit Fo − Fc difference density map contoured at 3 σ showing density for a bound phosphate.

To determine whether Gln-46 is required for normal helical cell shape, we generated strains of H. pylori expressing Q46H and Q46A variants fused to a C-terminal 3x-Flag epitope integrated at the native locus. Both mutants exhibited nonhelical cell morphology consistent with a csd4 null phenotype of slightly curved or straight rods with occasional kinks or bends (Fig. 8, A and B) (8). Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibodies indicated no detectable differences in protein expression between the wild-type and mutant variants of Csd4 (Fig. 8D).

FIGURE 8.

Complementation and overexpression analysis of Csd4 active site variants. Strain labels indicate the copy number (1 or 2) and amino acid residue at position 46 (Q, A, or H) of csd4–3x-Flag. Strains with two copies have one copy at the native locus and the second copy at the rdxA locus. The strains used were (−) LSH100 WT (no 3x-Flag tag), KBH54 (Δcsd4), KBH19 (1Q), KBH33 (1H), KBH42 (1A), KBH60 (2H), KBH65 (2Q), and KBH66 (1Q, 1H). A–C, 1000× phase contrast images of wild-type (A) and csd4 mutant H. pylori (B and C) smooth histograms displaying population cell curvature (x axis, B) and population axis length (x axis, C) as a density function (y axis). D, Western blot analysis of Csd4 (detected by anti-Flag M2 antibody, predicted molecular mass of 48 kDa) and Cag3 (periplasmic protein loading control, predicted molecular mass is 55 kDa). Equivalent amounts of cell extract based on optical density of the culture were loaded for each strain. ImageJ software was used for densitometry analysis of Csd4 variant expression relative to Cag3 and is indicated below each lane. M.w, molecular mass; rel. exp., relative expression.

Because the Q46H mutant retained some m-DAP cleavage activity in vitro, we generated a merodiploid strain expressing a second copy of csd4 Q46H-3x-Flag (KBH60) at the rdxA locus (used for csd4 complementation in previous studies) (8) to explore whether overexpression of the Q46H variant might rescue helical shape. Although we observed a 2.4-fold higher protein expression in the strain expressing two copies of csd4Q46H (Fig. 8D), we saw no restoration of helical morphology (Fig. 8, A and B). In contrast, a strain expressing two copies of the Q allele (KBH65) supports normal morphology in most cells (Fig. 8A) but has an increased population of straight cells that have side curvature values less than 4 compared with the strain with a single copy of the Q allele (Fig. 8B), as was reported previously (10). The perturbation of cell shape during overexpression was suggested to result from a requirement of precise asymmetric localization of Csd4 activity to generate proper helical curvature. In this model, loss of expression prevents the induction of curvature whereas extra protein expression at additional sites may break asymmetry and again lead to loss of curvature. We then created a strain expressing the wild-type csd4 allele at the native locus and the csd4Q46H allele at rdxA (KBH66) and observed a dominant-negative effect of the csd4Q46H allele with a complete loss of helical cell morphology (Fig. 8, A and B). This unexpected result may suggest that in cells Csd4 acts cooperatively in a complex. Previously we observed an increase in cell length in a wild-type csd4 merodiploid strain (10). Interestingly, all strains containing two copies of csd4 show increased cell length regardless of whether one or both copies contain Q46H (Fig. 8D). Taken together with the in vitro activity data, these results suggest that the Q46H variant is unable to generate helical cell morphology caused by a perturbation of enzyme activity, but enzymatic activity is not required for the effects of Csd4 on cell length (Fig. 8C).

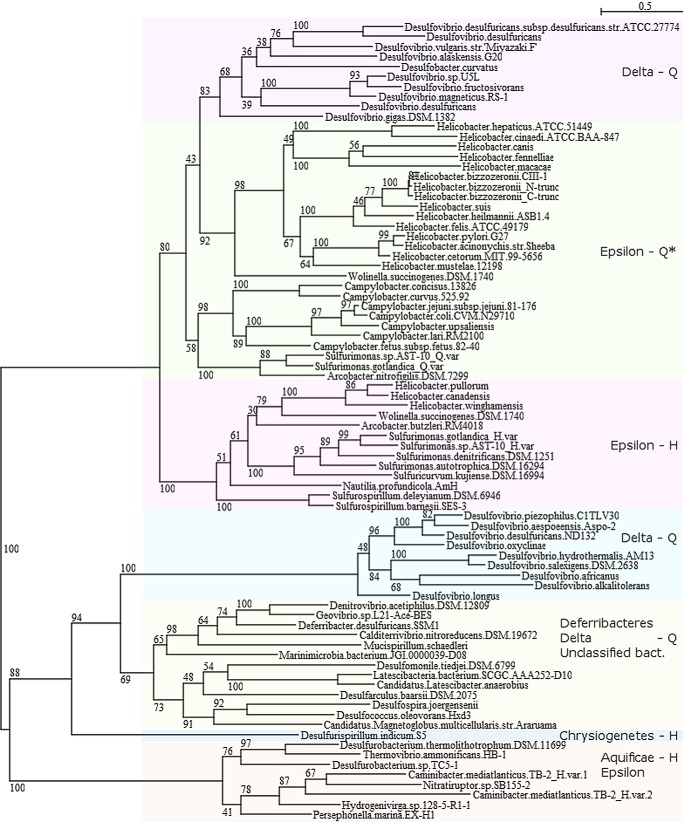

Csd4 as an Archetype for a New Family of CPs

A sequence analysis of Csd4 homologs was performed to identify conserved features. Bacterial homologs containing all three domains of Csd4 were identified based on a sequence similarity search; the sequences were aligned, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed (Figs. 9 and 10). Homologs were identified primarily within the δ and ϵ Proteobacteria, Deferribacteres, and Aquificae (9). Although primarily found in helical or curved rod-shaped organisms, homologs of Csd4 were identified in a number of rod-shaped bacteria, including ones isolated from deep sea hydrothermal vents and coastal sediments. Homologs of Csd4 generally cluster based on bacterial class and by the presence of the Gln zinc ligand versus an equivalent His. However, Helicobacter homologs fall into two distinct branches. The first branch includes H. pylori and other ϵ-Proteobacteria (group Epsilon-Q*). All members of this branch contain a Gln at position equivalent to Gln-46 except for Helicobacter hepaticus and Helicobacter cinaedi, which contain a histidine but are still helical. Additionally, five of these Helicobacter species, including H. hepaticus and H. cinaedi, contain an extended C-terminal region of ∼200–300 residues as compared with Csd4. The second branch contains ϵ-Proteobacteria and have the His variation at position 46 (group Epsilon-H).

FIGURE 9.

Conservation of zinc and substrate binding residues for select homologs of Csd4. Shown are H. pylori G27 (H.py) YP_002265985.1, Helicobacter canis (H.ca) WP_023929364.1, H. hepaticus ATCC 51449 (H.he) NP_860063.1, Helicobacter pullorum (H.pu) WP_005022665.1, C. jejuni 81–176 (C.je) YP_001001002.1, Desulfovibrio vulgaris str. Miyazaki F (D.vu) YP_002436677.1, Sulfurimonas gotlandica GD1 (S.go 1, SMGD1_0946, WP_008338748.1; S.go 2, SMGD1_2299, WP_008339471.1), Sulfurimonas denitrificans DSM 1251 (S.de) YP_393892.1, Wolinella succinogenes DSM 1740 (W.su 1, WS0230, NP_906487.1; W.su 2, WS0783, NP_906997.1), Arcobacter nitrofigilis DSM 7299 (A.ni) YP_003657196.1, Arcobacter butzleri RM4018 (A.bu) YP_001489842.1, Persephonella marina EX-H1 (P.ma) YP_002731141.1, Caminibacter mediatlanticus TB-2 (C.me 1, CMTB2_05747, WP_007475257.1; C.me 2, CMTB2_06881, WP_007473913.1), and Sulfurospirillum barnesii SES-3 (S.ba) YP_006404626.1. Only the regions containing the Csd4 carboxypeptidase domain are shown. Highlighted are key amino acid ligands in the Csd4 crystal structures: zinc-binding ligands (*), substrate/product binding residues ( ), hydrophobic binding pocket residues (+), and catalytically important glutamate (#).

FIGURE 10.

A bootstrapped tree of the Csd4 family of CPs. Homologs of Csd4 were identified from the nonredundant database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information utilizing BLASTP and an E value cutoff of 1 × 10−7. Identical protein sequences derived from different strains of the same species and proteins with short alignment coverage were removed. The sequences were aligned with Clustal Omega (28) and a bootstrapped tree (with 500 replicates, subtree pruning and regrafting and five random starts) was generated using PhyML (29) within Seaview (30). *, H. hepaticus and H. cinaedi form their own subbranch and contain a His at the equivalent position of Gln-46.

Whether the Csd4 homologs in those organisms play an active role in determining their shape is not currently known. The zinc ligands Glu-49 and His-128 are absolutely conserved among the identified Csd4 homologs. Although Gln-46 is required for full activity and helical shape of H. pylori, approximately one-quarter of the species identified have a histidine in the equivalent position. All of the bacteria isolated from deep sea vents, whether they belong to the phylum Aquificae or are ϵ-proteobacteria, have such a histidine. Although His-46-containing organisms include spiral-shaped species, the majority of deep sea vent isolates appear to be rod-like; however, whether these species have classical rod morphology is unknown.

DISCUSSION

Our product and substrate-bound crystal structures with an active site zinc gives further insight into cell wall substrate recognition and hydrolysis by enzymatically active Csd4 and expands our knowledge on the larger family of related funnelin CPs (15). In the Csd4 resting state, as represented by the Zn-Csd4 crystal structure, two water molecules are bound to the active site zinc. Substrate binding (i.e. TriZn-Csd4) displaces one of these two water molecules, leaving the other water positioned for nucleophilic attack of C7 of the substrate scissile amide bond. Glu-222 is the conserved glutamate positioned to act as the essential general base that abstracts a proton from the catalytic water to enhance nucleophilic attack on the amide carbonyl carbon (C7). Both zinc and Arg-86 are positioned to stabilize a negatively charged gem-diolate intermediate that is proposed in the generally accepted mechanism of CPs (15). In contrast to other funnelins, no Tyr residue is present to H-bond to the amide nitrogen. Protonation of the amide nitrogen by Glu-222 is associated with cleavage of the peptide bond. The PG dipeptide moiety appears to easily dissociate; however, the m-DAP remains bound and is likely displaced by the next PG tripeptide to repeat the cycle. Typically, funnelin family CPs hydrolyze the C-terminal residues of folded proteins in contrast to the isopeptide bond of the PG tripeptide. The unique structural features in Zn-Csd4 and TriZn-Csd4 may be a consequence of interacting with PG as the substrate. Recently, the crystal structures of muramyltripeptide and m-DAP bound Csd4 have been solved with calcium in the active site (35). As expected, the sugar moiety was not observable in the electron density (PDB code 4Q6N).

Most residues that bind the catalytic zinc or that interact with the substrate are highly conserved among the homologs of Csd4. Glu-222 is absolutely conserved in accordance with its proposed direct role in the Csd4 reaction mechanism. Moreover, mutation of Glu-222 in Csd4 alters H. pylori cell shape (8). Further insight into the Csd4 reaction may be gained by monitoring kinetics of residue variants, substrate analogs, and inhibitors such as phosphate. The two notable exceptions to the strict conservation of active site residues are the zinc ligand Gln-46 and His-126. His-126 interacts with m-DAP and is often replaced by polar uncharged residues, which may fulfill the same role. In some Csd4 homologs, Gln-46 is substituted by His, as observed in most funnelin CPs. Although the substitution of Gln to His requires a single point mutation, this residue is required for function and is largely conserved within branches of the Csd4 family. Additionally, the specific spatial positioning of a glutamine at position 46 appears to be required, because glutamine is not found in place of the other histidine zinc ligand, His-128.

The binding of phosphate at the zinc site in the structure of the Q46H variant may be due to structural similarity to the tetrahedral gem-diolate intermediate of the catalytic cycle. The rearrangement of Arg-86 and Glu-222 to accommodate this phosphate molecule may reflect the role of these residues in stabilization of the intermediate formed during normal catalysis. The observed inhibition of the activity of the Q46H variant by phosphate together with phosphate bound in the variant crystal structure suggests that coordination of the zinc by Gln in Csd4 may serve to prevent phosphate inhibition. Notably, phosphate was observed bound to Bacillus subtilis LdcB (34) and Streptococcus pneumoniae DacB (36), two ld-carboxypeptidases that remove the fourth amino acid from PG peptides and have a His-His-Asp zinc-binding motif. Although ld-CPs are also found in H. pylori (Csd6) (10) and C. jejuni (Pgp2) (37), neither are related to the Gram(+) ld-CPs, nor to dl-CPs such as Csd4.

Gln is required for Csd4 function yet is an uncommon zinc ligand. Zinc ligands play a key role in modulating the pKa and nucleophilicity of the bound catalytic water and therefore the activity of the enzyme. Gln is a polar amino acid that has a similar size and chemical properties as histidine, yet substitution of Gln-46 by His results in the loss of both CP activity and in vivo function. Zinc binding sites in proteins are typically formed by His, Cys, Glu, and Asp residues (33). A previous analysis in the PDB database found 6200 zinc-containing sites (38). From this list,4 we have found 12 wild-type entries, representing 6 proteins that are observed with Gln as a zinc ligand, none of which are peptidoglycan peptidases (Table 4). One well characterized example is human glyoxalase I, an unrelated zinc enzyme with a zinc site composed of a His, two Glu, and a Gln, whereas glyoxalase I from other organisms have a second His ligand instead of Gln. A Q33E variant of human glyoxalase I showed significantly reduced activity in vitro (1.3% of wild type) (39). However, a Q33H variant of human glyoxalase I was not examined, and therefore whether there is a similar deleterious effect as the Q46H substitution in Csd4 is not clear.

TABLE 4.

Characterized Gln-containing zinc proteins identified from the Protein Data Bank

| Protein | Organism | PDB code | Zinc ligands | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphomannose isomerase | Candida albicans | 1pmi | Q-H-E-H-H2O | Isomerase |

| Glyoxalase I | Human, mouse | 1bh5, 1fro, 1qip, 1qin, 2za0 | H-E-Q-E-H2O | Lyase |

| ING4 | Human | 2k1j | Q-H (and 2 weak C interactions) | Gene regulation/zinc finger |

| l-Histidinol dehydrogenase | E. coli | 1kae | Q-H-D-H | Oxidoreductase |

| Glucose dehydrogenase I | Sulfolobus solfataricus (archaea) | 2cd9 | C-H-E-Q | Oxidoreductase |

| 5′-Nucleotidase | E. coli | 1hp1, 1ush, 2ush | D-H-D-Q | Hydrolase |

Typical to the members of the M14 family, the tripeptide binding pocket of Csd4 forms a characteristic cul-de-sac that determines substrate length and specificity. At the bottom of this pocket in Csd4 is Thr-208, an absolutely conserved residue that forms a H-bond to the terminal amine of the m-DAP moiety through the side chain Oγ (3.0 Å). The equivalent position is responsible for substrate specificity in other CPs. An example is subfamily M14A, which is further subdivided into A-type (e.g. carboxypeptidase A) and B-type (e.g. carboxypeptidase B) enzymes (15). In A-type CPs, Thr-208 is replaced by small hydrophobic residues to preferentially interact with aromatic or small aliphatic side chains, whereas B-type CPs, which prefer substrates terminating in basic amino acids, have a negatively charged residue at the position equivalent to 208. The presence of Thr-208 rather than an acidic residue like in B-type CPs in part explains the lack of detectable activity on hippuryl-Lys, a chromogenic substrate commonly used to assay the activity of B-type carboxypeptidases (data not shown). The Csd4 substrate binding pocket is designed to accommodate the stem tripeptide portion of PG but does not have sufficient space for a fourth amino acid, explaining the lack of activity on a disaccharide tetrapeptide substrate analog reported previously (8).

Csd4 shares similar substrate preferences to members of subfamily M14C, characterized by two bacterial CPs involved in the cleavage of murein-derived substrates: endopeptidase I from Lysinibacillus sphaericus and the E. coli murein peptide amidase (MpaA). Although both enzymes are CPs and have a canonical zinc binding motif, neither has detectable sequence similarity to Csd4 by BLAST analyses (E values > 0.1). Endopeptidase I cleaves m-DAP-d-Ala from the PG tetrapeptide (dl-endopeptidase activity) and also m-DAP from the tripeptide (dl-carboxypeptidase activity) (40). The CP domain of endopeptidase I is preceded by two tandem copies of a LysM domain predicted to bind PG. Conversely, MpaA is a single domain cytoplasmic CP involved in the catabolic usage of murein-derived peptides as a nutrient source. Unlike Csd4, MpaA cleaves murein tripeptides but has little to no activity on N-acetylmuramic acid tripeptides and tetrapeptides (41). The structure of the Vibrio harveyi MpaA homolog (solved only in the apo form) shows overall homology to other CPs including Csd4 but contains an extra loop region over the substrate binding site that is proposed to determine the preference for small, sugarless substrates. The absence of such a loop in Csd4 is consistent with its ability to interact with the large intact PG sacculus.

Csd4 is a structurally unique CP that hydrolyzes tripeptides to modify PG. We have shown that Csd4 contains an M14-type domain and has the requisite dl-carboxypeptidase activity to release m-DAP using a zinc site with a Gln ligand. Interestingly, the MEROPS database of CPs (12) currently lists Helicobacter as a genus lacking any members of the M14 family of CPs and a BLAST search of the Csd4 sequence against this database yields CP sequences with only weak significance scores (E values > 1 × 10−3). In addition, Csd4 and its close homologs contain two additional C-terminal domains that are unlike those found in the other characterized M14 subfamilies. Therefore, we propose that Csd4 be defined as the prototypical member of a new subfamily tentatively named M14E.

Open questions include how Csd4 functions within the context of the bacterial cell. The C-terminal domains play a role in Csd4 stability within the bacterial cell but may have additional functions in coordinating Csd4 localization through interactions with other shape determining proteins or the PG itself. Although overexpression of the Q46H variant did not support helical cell shape generation, it did promote the increased cell length previously observed during overexpression of wild-type Csd4 (10), suggesting additional functions for the protein that do not require enzymatic activity. H. pylori Csd3, an unrelated M23B family metallopeptidase, was shown to have dd-carboxypeptidase activity and can produce tetrapeptides from un-cross-linked pentapeptides (42). In turn, the tetrapeptide-cleaving ld-carboxypeptidase Csd6 was recently shown to provide the tripeptide substrate for Csd4. Overexpression (as well as loss) of either Csd4 or Csd6 perturbs helical morphology; thus peptide hydrolysis by Csd4 to achieve a helical bacterial shape is likely to require precise spatial coordination within the PG layer (10).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1A1094839 and T32CA009657. This work was also supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery grants (to M. E. P. M. and M. E. T.) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grant MOP-68981 (to E. G.). This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (to K. B.) under Grant DGE-1256082. Support for infrastructure for structural biology was provided by the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (to M. E. P. M.). The research described in this paper was performed using Beamlines 08B1-1 and 08ID-1 at the Canadian Light Source, which is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the National Research Council Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Province of Saskatchewan, Western Economic Diversification Canada, and the University of Saskatchewan.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4WCK, 4WCL, 4WCM, and 4WCN) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

C. Andreini, personal communication.

- PG

- peptidoglycan

- CP

- carboxypeptidase

- DAPDH

- diaminopimelate dehydrogenase

- TBS-T

- Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20

- r.m.s.

- root mean square

- m-DAP

- meso-1,6-diaminopimelate

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- HBTU

- N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium hexafluorophosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vollmer W., Blanot D., de Pedro M. A. (2008) Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 149–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sycuro L. K., Pincus Z., Gutierrez K. D., Biboy J., Stern C. A., Vollmer W., Salama N. R. (2010) Peptidoglycan crosslinking relaxation promotes Helicobacter pylori's helical shape and stomach colonization. Cell 141, 822–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young K. D. (2006) The selective value of bacterial shape. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 660–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schleifer K. H., Kandler O. (1972) Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriol. Rev. 36, 407–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wyckoff T. J., Taylor J. A., Salama N. R. (2012) Beyond growth: novel functions for bacterial cell wall hydrolases. Trends Microbiol. 20, 540–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frirdich E., Gaynor E. C. (2013) Peptidoglycan hydrolases, bacterial shape, and pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 767–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Typas A., Banzhaf M., Gross C. A., Vollmer W. (2012) From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 123–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sycuro L. K., Wyckoff T. J., Biboy J., Born P., Pincus Z., Vollmer W., Salama N. R. (2012) Multiple peptidoglycan modification networks modulate Helicobacter pylori's cell shape, motility, and colonization potential. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frirdich E., Biboy J., Adams C., Lee J., Ellermeier J., Gielda L. D., Dirita V. J., Girardin S. E., Vollmer W., Gaynor E. C. (2012) Peptidoglycan-modifying enzyme Pgp1 is required for helical cell shape and pathogenicity traits in Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sycuro L. K., Rule C. S., Petersen T. W., Wyckoff T. J., Sessler T., Nagarkar D. B., Khalid F., Pincus Z., Biboy J., Vollmer W., Salama N. R. (2013) Flow cytometry-based enrichment for cell shape mutants identifies multiple genes that influence Helicobacter pylori morphology. Mol. Microbiol. 90, 869–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salama N. R., Hartung M. L., Müller A. (2013) Life in the human stomach: persistence strategies of the bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 385–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rawlings N. D., Barrett A. J., Bateman A. (2012) MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D343–D350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lipscomb W. N., Sträter N. (1996) Recent advances in zinc enzymology. Chem. Rev. 96, 2375–2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frey P. A., Hegeman A. D. (2007) Enzymatic Reaction Mechanisms, Oxford University Press USA, New York [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gomis-Rüth F. X. (2008) Structure and mechanism of metallocarboxypeptidases. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 319–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agnihotri G., Ukani R., Malladi S. S., Warshakoon H. J., Balakrishna R., Wang X., David S. A. (2011) Structure-activity relationships in nucleotide oligomerization domain 1 (Nod1) agonistic gamma-glutamyldiaminopimelic acid derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 54, 1490–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2005) Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (Walker J. M. ed.) pp. 571–607, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hor L., Peverelli M. G., Perugini M. A., Hutton C. A. (2013) A new robust kinetic assay for DAP epimerase activity. Biochimie 95, 1949–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horton R. M. (1995) PCR-mediated recombination and mutagenesis. SOEing together tailor-made genes. Mol. Biotechnol. 3, 93–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pinto-Santini D. M., Salama N. R. (2009) Cag3 is a novel essential component of the Helicobacter pylori Cag type IV secretion system outer membrane subcomplex. J. Bacteriol. 191, 7343–7352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Copass M., Grandi G., Rappuoli R. (1997) Introduction of unmarked mutations in the Helicobacter pylori vacA gene with a sucrose sensitivity marker. Infect. Immun. 65, 1949–1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Terry K., Williams S. M., Connolly L., Ottemann K. M. (2005) Chemotaxis plays multiple roles during Helicobacter pylori animal infection. Infect. Immun. 73, 803–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sheldrick G. M. (2010) Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perrakis A., Morris R., Lamzin V. S. (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D., Gibson T. J., Karplus K., Li W., Lopez R., McWilliam H., Remmert M., Söding J., Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gouy M., Guindon S., Gascuel O. (2010) SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ashkenazy H., Erez E., Martz E., Pupko T., Ben-Tal N. (2010) ConSurf 2010: calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W529–W533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Holm L., Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sousa S. F., Lopes A. B., Fernandes P. A., Ramos M. J. (2009) The zinc proteome: a tale of stability and functionality. Dalton Trans. 7946–7956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoyland C. N., Aldridge C., Cleverley R. M., Duchêne M. C., Minasov G., Onopriyenko O., Sidiq K., Stogios P. J., Anderson W. F., Daniel R. A., Savchenko A., Vollmer W., Lewis R. J. (2014) Structure of the LdcB LD-carboxypeptidase reveals the molecular basis of peptidoglycan recognition. Structure 22, 949–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim H. S., Kim J., Im H. N., An D. R., Lee M., Hesek D., Mobashery S., Kim J. Y., Cho K., Yoon H. J., Han B. W., Lee B. I., Suh S. W. (2014) Structural basis for the recognition of muramyltripeptide by Helicobacter pylori Csd4, a D,L-carboxypeptidase controlling the helical cell shape. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 2800–2812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Abdullah M. R., Gutiérrez-Fernández J., Pribyl T., Gisch N., Saleh M., Rohde M., Petruschka L., Burchhardt G., Schwudke D., Hermoso J. A., Hammerschmidt S. (2014) Structure of the pneumococcal l,d-carboxypeptidase DacB and pathophysiological effects of disabled cell wall hydrolases DacA and DacB. Mol. Microbiol. 93, 1183–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Frirdich E., Vermeulen J., Biboy J., Soares F., Taveirne M. E., Johnson J. G., DiRita V. J., Girardin S. E., Vollmer W., Gaynor E. C. (2014) Peptidoglycan LD-carboxypeptidase Pgp2 influences Campylobacter jejuni helical cell shape and pathogenic properties and provides the substrate for the DL-carboxypeptidase Pgp1. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 8007–8018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Andreini C., Bertini I. (2012) A bioinformatics view of zinc enzymes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 111, 150–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ridderström M., Cameron A. D., Jones T. A., Mannervik B. (1998) Involvement of an active-site Zn2+ ligand in the catalytic mechanism of human glyoxalase I. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21623–21628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garnier M., Vacheron M. J., Guinand M., Michel G. (1985) Purification and partial characterization of the extracellular gamma-d-glutamyl-(L)meso-diaminopimelate endopeptidase I, from Bacillus sphaericus NCTC 9602. Eur. J. Biochem. 148, 539–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maqbool A., Hervé M., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Wilkinson A. J., Thomas G. H. (2012) MpaA is a murein-tripeptide-specific zinc carboxypeptidase that functions as part of a catabolic pathway for peptidoglycan-derived peptides in gamma-proteobacteria. Biochem. J. 448, 329–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bonis M., Ecobichon C., Guadagnini S., Prévost M. C., Boneca I. G. (2010) A M23B family metallopeptidase of Helicobacter pylori required for cell shape, pole formation and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 809–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laskowski R. A., Swindells M. B. (2011) LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51, 2778–2786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]