Abstract

Tamoxifen reduces the rate of breast cancer recurrence by approximately a half. Tamoxifen is metabolized to more active metabolites by enzymes encoded by polymorphic genes, including cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6). Tamoxifen is a substrate for ATP-binding cassette transporter proteins. We review tamoxifen's clinical pharmacology and use meta-analyses to evaluate the clinical epidemiology studies conducted to date on the association between CYP2D6 inhibition and tamoxifen effectiveness. Our findings indicate that the effect of both drug-induced and/or gene-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 activity is likely to be null or small, or at most moderate in subjects carrying two reduced function alleles. Future research should examine the effect of polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes in tamoxifen's complete metabolic pathway, should comprehensively evaluate other biomarkers that affect tamoxifen effectiveness, such as the transport enzymes, and focus on subgroups of patients, such as premenopausal breast cancer patients, for whom tamoxifen is the only guideline endocrine therapy.

Keywords: ATP-binding cassette transporter, breast cancer, breast cancer recurrence, cytochrome P450 2D6, multiple drug resistance, P-glycoprotein, polymorphism, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, tamoxifen

The selective ER modulator tamoxifen could be considered the first targeted cancer therapy. For more than 25 years, tamoxifen has been used in routine clinical practice as the ‘gold standard’ treatment for ER+ breast tumors [1,2]. Two-thirds of breast cancer patients have tumors that express the ER and are, therefore, candidates for endocrine therapy. Current treatment guidelines recommend tamoxifen as the only endocrine therapy for premenopausal women, in whom other endocrine therapies, such as aromatase inhibitors, are contraindicated [3,4,201]. Aromatase inhibitors are the treatment of choice for postmenopausal women, but tamoxifen remains an important alternative or sequential treatment for these patients, depending on their risk of treatment-induced adverse events. Tamoxifen is, therefore, a cornerstone of adjuvant breast cancer therapy. Tamoxifen reduces the risk of breast cancer recurrence by approximately a half and the risk of mortality by approximately a quarter [5,6]. Nonetheless, patients with very similar clinical characteristics and prognostic factors at diagnosis, who receive the same tamoxifen treatment regimen, can vary substantially in their treatment response and, hence, the clinical course of their disease. Some patients develop recurrent disease, resistant to tamoxifen, and many eventually die of their cancer. Despite over 25 years in clinical use, and a substantial literature focused on resistance to tamoxifen, predictors of tamoxifen effectiveness in women with ER+ disease remain elusive.

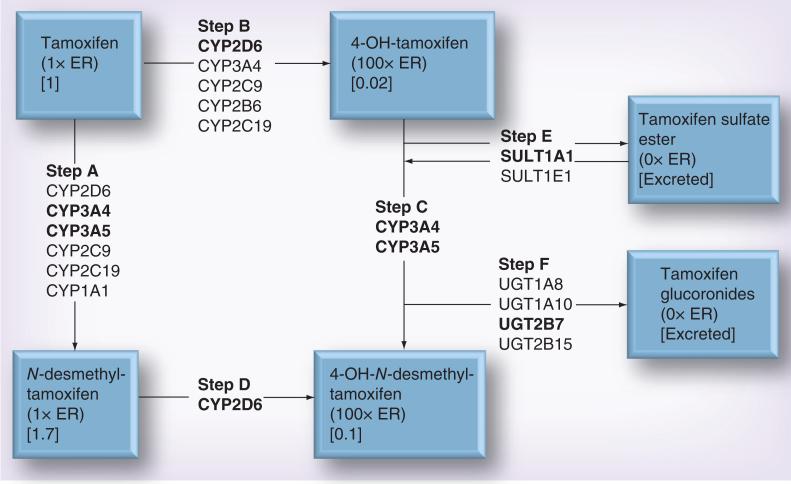

Tamoxifen is metabolized to more active forms by various cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19) (Figure 1) [7–11]. Each metabolite has its own specific binding affinity for the ER [12]. The tamoxifen derivatives with hydroxyl groups attached to their four-carbon have the highest binding affinities to the ER. The UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes (primarily UGT1A8, UGT1A10, UGT2B7 and UGT2B15) [13,14] and sulfotransferase enzymes (primarily SULT1A1) [15] catalyze the conversion of tamoxifen metabolites into excretable forms. All enzymes in tamoxifen's metabolic pathway are polymorphic. Thus, interindividual differences in tamoxifen metabolism contribute to variation in the concentration of metabolites in the serum, and potentially drug effectiveness.

Figure 1. Major metabolic pathways for tamoxifen.

Bold font denotes the enzyme(s) primarily involved in each step. Numbers in square parentheses denote plasma concentration of the metabolite, relative to tamoxifen's concentration, after 4 months of tamoxifen therapy at 20 mg per day. The binding affinity to ER relative to tamoxifen itself is also shown.

Three members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters – ABCB1 (P-gp/MDR1), ABCC1 (BRCP) and ABCC2 (MRP2) – are also key players in the drug resistance phenotype. These transporter proteins are normally expressed at the luminal side of enterocytes, brain capillary endothelial cells, bile canaliculi and in the proximal tubules of the kidney in germline cells. They transport a wide variety of toxins, nutrients, environmental carcinogens and drugs out of the cells. As the proteins mediate drug efflux, they are also frequently overexpressed in solid tumors and tumor cell lines, promoting drug resistance and concomitant cancer cell survival [16–20]. ABCB1 is expressed in 28–63% of breast tumors, depending on the methodology applied [21]. Polymorphisms in the genes encoding these transporter proteins can result in an increased expression and reduce the effectiveness of cancer drugs. The primary ER-binding metabolites of tamoxifen – 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl tamoxifen (also known as endoxifen) and 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Figure 1) – bind ABCB1 and are in vitro substrates of the ABCB1 transporter [22,23]. However, the effect of these polymorphisms on tamoxifen effectiveness is not clear.

Although the metabolism and transport of tamoxifen is quite complicated, involving multiple polymorphic enzymes, the majority of the research studies to date have focused on CYP2D6. This enzyme is important to generating 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl tamoxifen, which is the most abundant of the high-affinity 4-hydroxylated metabolites. Here, we comprehensively evaluate the evidence to date on the association between CYP2D6 inhibition and tamoxifen effectiveness through a review and meta-analysis of the literature regarding the association between drug- and gene-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 and breast cancer outcomes. We highlight areas that have been understudied including the potential merit of evaluating polymorphisms in all genes encoding enzymes that metabolize and transport tamoxifen; the need for studies specifically focused on premenopausal women, for whom tamoxifen is the only guideline endocrine adjuvant therapy; and we discuss other biomarkers of tamoxifen effectiveness, such as transport enzymes, which have been understudied.

Methods

Search strategy & selection criteria

We began our review on CYP2D6 inhibition and the effectiveness of tamoxifen by searching the terms ‘tamoxifen’ and ‘CYP2D6’ in PubMed. We did not impose language restrictions. We retrieved all manuscripts published up to 1 March 2013, on drug- or gene-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 activity and tamoxifen effectiveness as measured by breast cancer outcomes. We also used citation lists within each of the included scientific papers to ensure we included all scientific work, including conference abstracts, on CYP2D6 inhibition and tamoxifen effectiveness.

Meta-analyses

We generated four meta-analytic models to investigate population-based studies focused on concurrent use of medicines that are weak (1.25–2-fold increase in area under the curve [AUC] of enzyme substrate), moderate (>2–5-fold increase in AUC of enzyme substrate) or strong (>5-fold increase in AUC of enzyme substrate) CYP2D6 inhibitors (especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) and breast cancer outcomes (breast cancer recurrence or breast cancer mortality in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen). We ran two separate models, first, population-based studies of the association of any nonfunctional variant (i.e., homozygote and heterozygote carriers) of CYP2D6 and breast cancer recurrence or mortality, and second, two nonfunctional variants (i.e., homozygote carriers) of CYP2D6 and breast cancer recurrence or mortality in patients treated with tamoxifen. Where studies presented separate effect estimates showing the association of heterozygote and homozygote variant alleles, we estimated an inverse variance weighted average of these two associations. We then used the inverse variance weighted average of these two associations in the first of the gene-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 meta-analytic models.

Statistical analysis

We used random effects meta-analytic models to generate summary effect estimates. In all cases, estimates from fixed effect models were similar. We used funnel plots to assess for evidence of publication bias in the meta-analyses. All analyses were performed using STATA software, version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, TX, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

The studies included in our meta-analysis used very different protocols in terms of data collection, analysis and interpretation. However, we opted to include all available studies, rather than a particular type of study, to avoid the appearance that studies were selected for inclusion on the basis of their results. We used random effects meta-analytic models to recognize the heterogeneity across the studies, acknowledging that effects may be different in the different study populations. The quantitative meta-analysis in itself gives no indication of study biases and limitations, but, as outlined below, each graph highlights the near null association, especially when considered together with our qualitative review.

Drug-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 activity & tamoxifen effectiveness: the example of SSRIs & CYP2D6 function

The antiestrogenic and estrogenic actions of tamoxifen induce side-effects, which can be mildly to severely debilitating. These include hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms, depression (either pre-existing depression or depression due to the diagnosis of breast cancer), venous thromboembolism and endometrial cancer [24–30]. SSRIs are frequently prescribed to control such depressive and vasomotor side effects of tamoxifen treatment. SSRIs and tamoxifen are both metabolized by CYP2D6 [9,31–33]. Concurrent use of SSRIs and tamoxifen can result in competitive inhibition or direct inhibition of the metabolism of tamoxifen. The net effect is a reduced plasma concentration of the tamoxifen metabolite, 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyltamoxifen [10,34]. Thus, the effect of concurrent use of tamoxifen and SSRIs on breast cancer recurrence and survival is controversial [35,36]. Different SSRIs precipitate CYP2D6 inhibition to varying degrees [33]. The most potent and effective inhibitors are paroxetine and fluoxetine. These drugs convert phenotypically extensive or intermediate CYP2D6 metabolizers into poor metabolizers, phenotypically equivalent to subjects carrying two nonfunctional CYP2D6 alleles. By contrast, other SSRIs, citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline and fluvoxamine, only weakly inhibit CYP2D6. Studies have reported decreased plasma concentrations of the tamoxifen metabolite, 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl-tamoxifen, in women who used the strong CYP2D6 inhibitor drugs, paroxetine or fluoxetine, concurrent to their tamoxifen treatment. The same studies also report intermediate concentrations of 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl-tamoxifen in women who used the weaker CYP2D6 inhibitors sertraline and citalopram concurrently to tamoxifen, and little to no impact on 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl-tamoxifen plasma concentrations among women who used the selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine (a weak CYP2D6 inhibitor) concurrent to tamoxifen treatment [10,34,37,38].

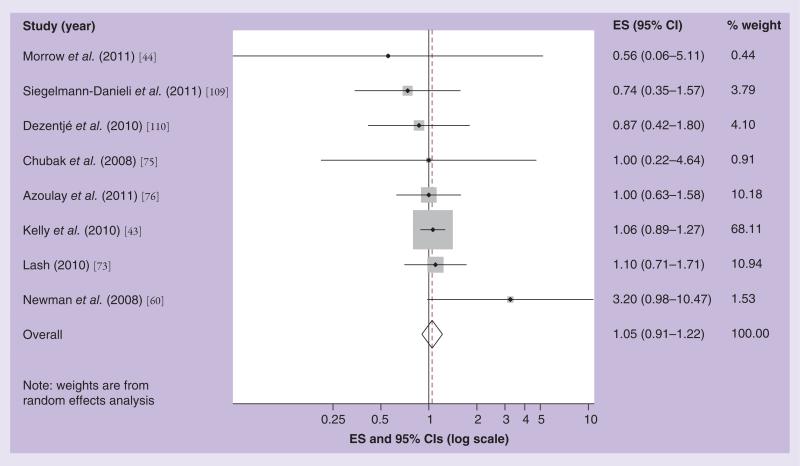

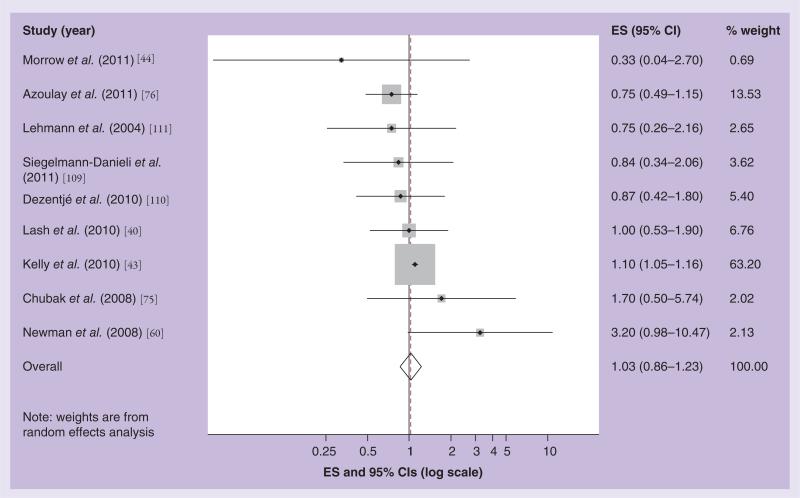

Twelve clinical epidemiology studies have investigated the effect of concomitant use of SSRIs and tamoxifen on breast cancer recurrence with heterogeneous findings. Three studies used overlapping patient populations and follow-up time [39–41], we, therefore, included the most up-to-date and relevant report in our meta-analyses [42]. Figure 2 shows the results of our meta-analysis focused on drugs that weakly inhibit CYP2D6 function (i.e., citalopram). The Kelly et al. study had the highest weight (68% of the total), as indicated by the relative size of the shaded square on the graph surrounding its effect estimate [43]. The study with the lowest weight was a case–control study by Morrow et al., which had very few exposed cases (n = 2), and, therefore, imprecise estimates. The summary estimate in the random effects meta-analysis model associating breast cancer recurrence with concomitant use of tamoxifen and a weak SSRI was 1.05, with 95% CI: 0.91–1.22 [44]. Figure 3 shows the results of our random effects meta-analytic model for the association of strong CYP2D6 inhibitor SSRIs and tamoxifen effectiveness. Again, the Kelly et al. study had the highest weight [43]. The summary effect estimate was 1.03, with 95% CI: 0.86–1.23. For both weak and strong CYP2D6 inhibitors, our funnel plots did not suggest publication bias. Thus, our summary effect estimates do not suggest any evidence of an effect of concurrent use of SSRIs and tamoxifen on breast cancer recurrence.

Figure 2. Effect size and 95% CIs for the association between concurrent use of a weak cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor drug and breast cancer recurrence/survival.

Summary ES and 95% CIs were estimated using a random effects meta-analytic model. All statistical tests were two-sided. The size of each square is an illustrative representation of the study weight. The horizontal lines represent the confidence intervals. The diamond (outline) represents the summary effect estimate and diamonds (solid) are the effect estimates for each individual study. The dashed line shows the pooled summary estimate for each meta-analytic model.

ES: Effect size.

Figure 3. Effect size and 95% CIs for the association between concurrent use of a strong cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor drug and breast cancer recurrence/survival.

Summary ES and 95% CIs were estimated using a random effects meta-analytic model. All statistical tests were two-sided. The size of each square is an illustrative representation of the study weight. The horizontal lines represent the confidence intervals. The diamond (outline) represents the summary effect estimate and diamonds (solid) are the effect estimates for each individual study. The dashed line shows the pooled summary estimate for each meta-analytic model.

ES: Effect size.

Gene-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 activity & tamoxifen effectiveness: the example of the CYP2D6*4 & *10 variants & breast cancer outcomes in tamoxifen-treated patients

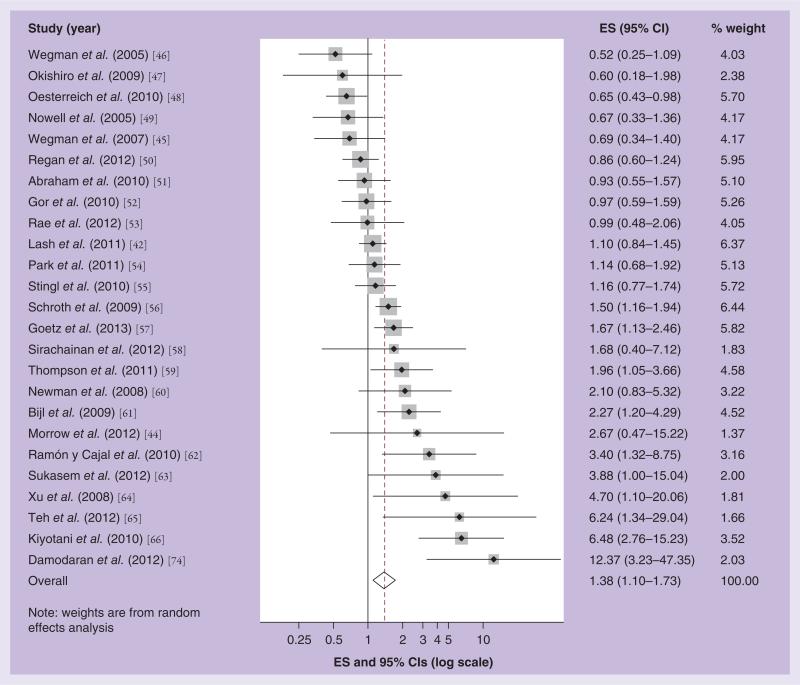

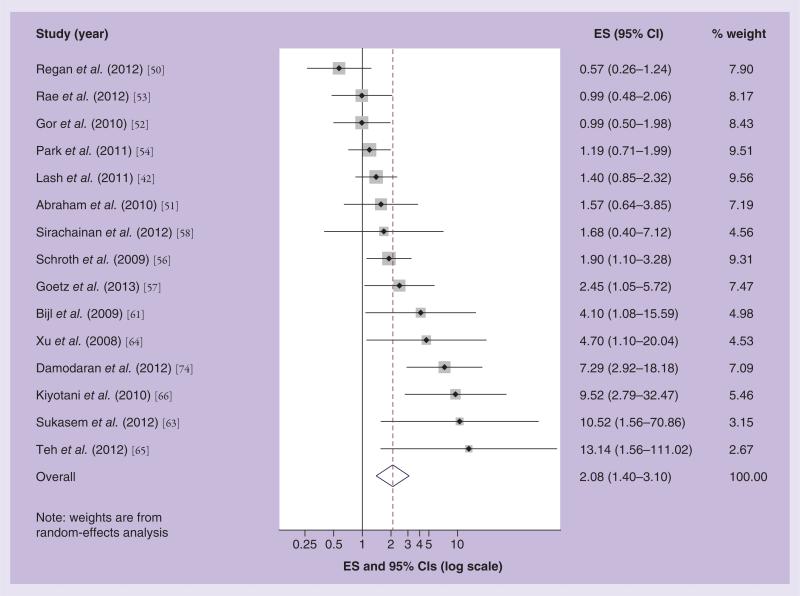

To date, 30 studies have investigated the association between gene-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 function and the effectiveness of adjuvant tamoxifen treatment [42,44–66]. Where studies were updates of earlier reports, [56,66–69] and had overlapping patient groups and follow-up time, we included the most recent reports in the meta-analyses [66,70]. In addition, we excluded two studies, which reported null findings, as we were unable to extract estimates of association from them [71,72]. Figures 4 & 5 show the results of our random effects meta-analytic models associating the inheritance of the CYP2D6*4 or *10 allele with breast cancer outcomes in the published studies. Overall, the studies showed substantial heterogeneity in their results (p for test of homogeneity < 0.001), and the study-specific effect estimates are distributed evenly either side of the null. The wide confidence intervals indicate poor precision in many of the studies. The poor precision and heterogeneous nature of the results published to date caution against any evidence of a strong effect of gene-induced CYP2D6 inhibition and tamoxifen effectiveness.

Figure 4. Effect size and 95% CIs for the association between inheritance of any nonfunctional variant of CYP2D6*4 or CYP2D6*10 and breast cancer recurrence/survival.

Summary ES and 95% CIs were estimated using a random effects meta-analytic model. All statistical tests were two-sided. The size of each square is an illustrative representation of the study weight. The horizontal lines represent the confidence intervals. The diamond (outline) represents the summary effect estimate and diamonds (solid) are the effect estimates for each individual study. The dashed line shows the pooled summary estimate for each meta-analytic model.

ES: Effect size.

Figure 5. Effect size and 95% CIs for the association between inheritance of two nonfunctional variants of CYP2D6*4 or CYP2D6*10 and breast cancer recurrence/survival.

Summary ES and 95% CIs were estimated using a random effects meta-analytic model. All statistical tests were two-sided. The size of each square is an illustrative representation of the study weight. The horizontal lines represent the confidence intervals. The diamond (outline) represents the summary effect estimate and diamonds (solid) are the effect estimates for each individual study. The dashed line shows the pooled summary estimate for each meta-analytic model.

ES: Effect size.

In Figure 4 we present a Forest plot showing the association between the inheritance of any CYP2D6*4 or *10 allele and breast cancer recurrence or mortality in women treated with tamoxifen. The effect estimates ranged from 0.52 to 12.37. Nine studies reported associations below the null; sixteen studies reported associations above the null; while fifteen included the null in their 95% CI. The summary random effects estimate of 1.38, with 95% CI: 1.10–1.73, suggests a weak positive association. However, the studies with the greatest weight, as indicated by the relative size of the shaded square surrounding their point estimate, are those with associations nearest to the null, except for the Schroth et al. and Goetz et al. studies [56,57]. However, as we have previously noted, the Schroth et al. study may have been null in the updated person-time included in the later analysis [73]. Our funnel plot shows some suggestion of publication bias, particularly bias towards the publication of studies with a positive association [65,66,74], but also some evidence of bias towards publication of those with a negative association [46,48].

Figure 5 shows a Forest plot of the association between two reduced function CYP2D6*4 or *10 alleles and breast cancer recurrence or mortality in tamoxifen-treated patients. The effect estimates reported in the studies range from 0.57 to 13.14. Three reported associations below the null; eight were above the null; and seven included the null in their 95% CI. The summary random effects estimate was 2.08, with 95% CI: 1.40–3.10. Again, we see some suggestion of bias towards the publication of positive [66,74] and negative results [50]. Overall, our findings suggest a non-null association between CYP2D6 inhibition among carriers of two reduced function alleles and recurrence risk. We note, however, that five studies with the strongest associations actually studied the CYP2D6*10 allele. The CYP2D6*10 allele reduces CYP2D6 activity rather than eliminates it, as is the case for CYP2D6*4. If CYP2D6 inhibition does affect outcome in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients, then it stands to reason that the greatest effect on the risks of recurrence or mortality would be among women with the CYP2D6*4 variant allele rather than the CYP2D6*10 allele.

Discussion

Drug-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 activity

Our meta-analyses show little evidence of an interactive effect between concomitant use of CYP2D6 inhibitor drugs and tamoxifen therapy on breast cancer recurrence. However, our graphs also highlight the inconsistency of the findings to date, which may be attributable to several factors. First, the inconsistency may be due to international variation in prescribing patterns. For example, in our study, we found that citalopram and escitalopram were the most frequently prescribed SSRIs in Denmark [42]. By contrast, a North American study reported that paroxetine and fluoxetine were prescribed most often [75], while a study based in the UK found that moderate-to-strong inhibitors and weak inhibitors were prescribed at approximately the same frequency [76]. Despite the variability in prescribing patterns in these three studies, all reported near-null results.

In addition, the source and quality of the drug exposure data has also varied widely across studies. Medication data have been retrieved retrospectively from medical record reviews or prospectively from prescription claims databases. It is important to note the difference in the two methods of recording prescription drug data. Retrospectively collected data indicates that information on SSRI drug use/prescriptions was collected after follow-up data on recurrence was recorded. By contrast, prospectively collected prescription data were recorded before information on breast cancer recurrence. The retrospectively collected drug data are susceptible to differential misclassification bias of the SSRI exposure [77]. Despite the variation in data collection, studies of both designs report null (e.g., [76,78]) and causal (e.g., [43,69]) associations between SSRI inhibition of CYP2D6 function and breast cancer recurrence.

Concerns about the safety regarding concurrent use of tamoxifen and SSRIs prompted an US FDA advisory committee to recommend a change to tamoxifen's label in 2006, noting that postmenopausal women with ER+ breast cancer who are poor CYP2D6 metabolizers – either due to genotype or due to drug interactions – may be at increased risk of breast cancer recurrence. Although the label change was not implemented, it raised awareness of the CYP2D6 and tamoxifen metabolism issue. Since then, some research indicates that the use of strong CYP2D6 inhibitors (i.e., paroxetine) concomitantly with tamoxifen has decreased (from 34% between 2004 and 2006 to 15% in 2010) [79], however, this has not been a consistent finding in western countries [80]. This decrease has been accompanied by a corresponding increase in the use of weak CYP2D6 inhibitors, from 32 to 52% over the same time period. Prior use of strong CYP2D6 inhibitors, comorbidity and frequent outpatient visits were determinants of strong inhibitor use after the FDA relabeling in 2006. These findings suggest that information on such potential drug interaction, whether warranted or not, has directly impacted prescribing trends in clinical practice.

Gene-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 activity

The discordant findings in the published literature regarding CYP2D6 genotype and breast cancer recurrence require consideration. Groups have argued that the only way to definitively solve this important clinical question is via a prospective clinical trial. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group E3108 trial is investigating CYP2D6 genotyping in a prospective setting [202]. However, in the interim, two trials of adjuvant tamoxifen, the BIG 1-98 [50] and the ATAC [53] trials, investigated CYP2D6 genotyping and tamoxifen response in subsets of their trial populations. Both reported null findings, and rejected the utility of CYP2D6 genotyping in determining response to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. However, these studies have received substantial criticisms, as outlined below [81–84], which were answered by the original authors. An initial criticism is that both studies genotyped DNA extracted from tumor tissue. CYP2D6 is located on chromosome 22q13, and there may be a loss of heterozygosity in breast tumors around this locus [85,86]. Such loss of heterozygosity would result in fewer heterozygotes in the study populations; a phenomenon that was observed in both trial populations as both studies exhibited departures from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) [50,53,81,87]. HWE is a fundamental law of genetics, frequently used as a quality control measure in genetic association studies. Deviations from HWE occur due to inbreeding, nonrandom mating, genetic drift, population stratification, differential survival of marker carriers, chance or genotyping error [88]. The reasons for departure from HWE in both trials are not clear. The authors of the BIG 1-98 CYP2D6 study highlighted that HWE was developed for biallelic autosomal genes. As CYP2D6 has several deletions and duplications, it may not conform to simple HWE [89,90]. Given the problems with HWE in both studies, it has also been argued that the use of tumor DNA to determine CYP2D6 genotype may not accurately reflect CYP2D6 levels in germline DNA [87]. However, we and others have found excellent concordance in CYP2D6 genotype in DNA extracted from tumors compared with that from paired nontumor tissue [91,92]. If tumor tissue is an invalid DNA source in this context, then it could be expected that all studies using tumor DNA would have similar findings on the association of CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen effectiveness. As Table 1 shows, studies that used tumor tissue as a source of DNA generally reported null or decreased risks of breast cancer recurrence associated with the CYP2D6 polymorphisms, while studies that used blood samples more often reported increased risks of recurrence. However, as we have already outlined, many of these studies with positive findings had important fundamental and methodological limitations, compromising the validity of their findings [93].

Table 1.

Proportion of premenopausal women in each study and its associated risk ratio, sorted by increasing risk ratio.

| Study (year) | Risk ratio | Premenopausal (%) | Genotype | DNA source | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20% premenopausal women | |||||

| Wegman et al. (2005) | 0.52 | 0 | *4 | Tumor | [46] |

| Wegman et al. (2007) | 0.69 | 0 | *4 | Tumor | [45] |

| Regan et al. (2012) | 0.86 | 0 | *3 *4 *6 *7 *10 *17 *41 | Tumor | [50] |

| Rae et al. (2012) | 0.99 | 0 | *2 *3 *4 *6 *10 *17 *41 | Tumor | [53] |

| Lash et al. (2011) | 1.1 | 6 | *4 | Tumor | [42] |

| Schroth et al. (2009) | 1.5 | 4 | *2 *3 *4 *5 *6 *7 *9 *10 *35 *41 | Tumor/blood | [56] |

| Goetz et al. (2013) | 1.67 | 0 | *3 *4 *6 *10 *41 | FFPE tumor and normal tissue | [57] |

| Bijl et al. (2009) | 2.27 | 0 | *4 | Blood | [61] |

| Damodaran et al. (2012) | 12.37 | 9 | *2 *4 *5 *10 *14 | Blood | [74] |

| ≥20% premenopausal women | |||||

| Okishiro et al. (2009) | 0.6 | 22 | *10 | Blood | [47] |

| Oesterreich et al. (2010) | 0.65 | † | † | † | [48] |

| Nowell et al. (2005) | 0.67 | 41 | *3 *4 *5 | FFPE tissue | [49] |

| Abraham et al. (2010) | 0.93 | 50 | *4 *5 *6 *9 *10 *41 | Blood | [51] |

| Gor et al. (2010) | 0.97 | 69 | *4 | Bone marrow/blood | [52] |

| Kim et al. (2010) | 1 | 50 | *3 *5 *10 *41 | † | [72] |

| Park et al. (2011) | 1.14 | >20 | *5 *10 *41 | Blood | [54] |

| Stingl et al. (2010) | 1.16 | 49 | *4 | Blood | [55] |

| Sirachainan et al. (2012) | 1.68 | 80 | *4 *5 *10 | Blood | [58] |

| Thompson et al. (2011) | 1.96 | 21 | *2 *3 *4 *5 *6 *7 *9 *10 *35 *41 | Blood | [59] |

| Newman et al. (2008) | 2.1 | 50 | *3 *4 *5 *41 | Blood | [60] |

| Morrow et al. (2012) | 2.67 | 20 | *2 *3 *4 *5 *6 *7 *9 *10 *17 *29 *35 *41 *1xN *2xN | Blood | [44] |

| Ramón y Cajal et al. (2010) | 3.4 | 43 | *2 *3 *4 *5 *6 *7 *9 *10 *20 *35 *41 | Blood | [62] |

| Sukasem et al. (2012) | 3.88 | 63 | *2 *5 *10 *36 *41 *4 *35 | Blood | [63] |

| Xu et al. (2008) | 4.7 | 24 | *10 | Blood | [64] |

| Teh et al. (2012) | 6.24 | 35 | *4 *5 *10 *14 | Blood | [65] |

| Kiyotani et al. (2010) | 6.48 | 52 | *4 *5 *6 *10 *14 *21 *36 *41 | Blood | [66] |

Data extracted from abstracts presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (TX, USA). The extent of genotyping, proportion of premenopausal women or DNA source could not be accurately estimated from the presented data.

FFPE: Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded.

Future perspective

To completely understand the interaction of CYP2D6 and tamoxifen effectiveness, future research should be directed at some critically important, but, understudied areas. First, a comprehensive evaluation of all polymorphic genes encoding enzymes within tamoxifen's metabolic path needs to be performed. Second, tamoxifen is the only endocrine therapy recommended for premenopausal women. Despite this, most studies have mainly included postmenopausal women. This calls for a focused investigation of the impact of CYP2D6 polymorphisms on tamoxifen effectiveness in premenopausal women. Third, a frenzy of research has examined enzymes that metabolize tamoxifen as predictors of response to the drug. However, only one study has examined the effect of polymorphic variation in transporters of tamoxifen, which may play a critical role in predicting response to the treatment. The study by Kiyotani et al. reported a null association, but the study had several limitations, including immortal person-time bias [66,94]. Below, we discuss some future perspectives.

Comprehensive genotyping of genes encoding enzymes involved in tamoxifen's entire metabolic pathway

Tamoxifen is metabolized to its most active form, 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl-tamoxifen, by a series of enzymes encoded by polymorphic genes. A major drawback of most of the studies conducted to date on cytochrome P450 enzyme function and tamoxifen effectiveness is their failure to comprehensively genotype the genes encoding enzymes in the complete tamoxifen metabolic pathway. It seems inconceivable that the effectiveness of tamoxifen hinges on only one allelic variant in a gene encoding a single enzyme in a very complex metabolic pathway (Figure 1).

To date, only one study, conducted in the prevention setting, comprehensively evaluated polymorphisms in the genes encoding enzymes in the entire tamoxifen metabolic pathway [95]. It found no evidence of a strong association between CYP2D6 variants in isolation and breast cancer incidence. However, it did report that CYP2D6 was a node that interacted with variant alleles in the other tamoxifen-metabolizing genes when the entire pathway was considered. If the effectiveness of tamoxifen relies on the activity of enzymes within its metabolic pathway, it will probably depend on changes in metabolic enzymes in the entire pathway, as well as their interaction. The literature to date strongly suggests that a more comprehensive genotyping strategy could provide a definitive answer on the effect of CYP2D6 polymorphisms and tamoxifen effectiveness.

Comprehensive genotyping of CYP2D6

Most studies have focused on genotyping CYP2D6*4 or *10 (the latter in Asian populations). Although CYP2D6*4 is the most prevalent nonfunctional allele, there are over 90 CYP2D6 polymorphic variants, and at least half of them affect enzymatic function [203]. To date, eight studies have genotyped CYP2D6*4 alone or CYP2D6*10 alone. All other studies genotyped at least one other CYP2D6 functional variant. The studies nested within the ATAC and BIG 1-98 trials genotyped seven and eight CYP2D6 alleles, respectively, both yielding null results [50,53]. A large cohort study by Abraham et al., genotyped the seven most prevalent CYP2D6 functional alleles and also reported a null result [51]. Despite this, in general, studies that genotyped more genes (i.e., more than the CYP2D6 gene only) reported higher effect estimates associated with CYP2D6 inhibition. This phenomenon could be expected if a failure to genotype all CYP2D6 variants caused nondifferential misclassification of the CYP2D6 functional phenotype. Such nondifferential misclassification would result in bias of the effect estimate associating reduced CYP2D6 function towards the null. This misclassification was reported in a study by Schroth et al., where a third of patients were misclassified on CYP2D6 function based on genotyping the *4 mutation alone [70]. More comprehensive genotyping (based on over 30 different mutations using AmpliChip®; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) resulted in greater inhibition of tamoxifen effectiveness, as measured by breast cancer recurrence. Accordingly, the effect estimate of breast cancer recurrence and poor CYP2D6 function increased from nearly null (1.3; 95% CI: 0.5–3.7) to being strongly positive (2.9; 95% CI: 1.4–6.1). A similar effect was seen in a study by Thompson et al., where comprehensive genotyping indicated an increased risk of recurrence associated with reduced CYP2D6 function [59].

We conducted a large population-based case–control study to examine the association between genetic markers of CYP2D6 inhibition and breast cancer recurrence [42]. As we only genotyped the *4 variant, we used a quantitative bias analysis to account for the lack of comprehensive genotyping data. In the bias analysis, we made an assumption that recurrent cases were more likely to carry reduced-function alleles than breast cancer patients who did not develop recurrent disease. We used published external data sources to inform the parameters of our bias model [42,96]. Our bias analysis suggested that comprehensive genotyping of CYP2D6 would not have changed the near null results. These findings are consistent with those of the Abraham et al. study and the BIG 1-98 and ATAC trial results [50,51,53]. In addition, in contrast to the results published from the BIG 1-98 and ATAC trial subsets and other studies of this topic, our genotyping results conformed to HWE despite using DNA extracted from tumor tissue.

Despite the intricate tamoxifen metabolic pathway, genetic polymorphisms of CYP2D6 have been the most studied enzymes in the pathway. This is probably attributable to the affinity of tamoxifen metabolites for the ER (4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl-tamoxifen has 100-fold greater affinity for the ER compared with tamoxifen), and also the higher serum concentration of 4-hydroxytamoxifen-N-desmethyltamoxifen. However, as previously noted [93,97], with standard-dose regimens, tamoxifen and its metabolites have such abundance in the serum, they are readily available to bind the ER in excess to the estrogen hormones with which they compete. This suggests that in women who are poor metabolizers (CYP2D6*4/*4 and women simultaneously taking paroxetine), tamoxifen and its metabolites should still be present at sufficiently high concentrations to exert their anti-tumorigenic effects. Future research should, therefore, study the genetic polymorphisms in the complete metabolic pathway, to enable the identification of gene–gene interactions that affect the activity of the tamoxifen metabolic enzymes.

Until recently, the statistical models required to evaluate complex gene–gene interactions had not been well developed [98]. However, Bayesian pathway modeling provides one approach to identify how multiple metabolites with different affinities for the ER will interact. Incorporating empirical Bayes shrinkage methods could reduce the potential for undue attention to be paid to potentially false-positive interactions. The Algorithm for Learning Pathway Structure incorporates Bayesian analysis and could be used to provide an estimate of the effect of the tamoxifen metabolic pathway on breast cancer recurrence.

CYP2D6 inhibition may be most likely to affect recurrence risk in premenopausal women

Tamoxifen and its metabolites compete with estrogen for binding to the ER, thereby inducing their anticancer effects [97,99]. The metabolites, 4-hydroxytamoxifen and 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl-tamoxifen, have approximately the same affinity for the ER as the naturally occurring estrogen, estradiol [100]. The concentration of estradiol in premenopausal women is more than tenfold that of postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen therapy further increases estradiol concentration [101]. Tamoxifen inhibition may, therefore, be most likely to affect recurrence risk in premenopausal women, where the full production of tamoxifen metabolites is necessary to compete with the abundant estrogen. Nonetheless, only one study (a poster presentation at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting in 2012) has focused on investigating metabolic inhibition and tamoxifen effectiveness in premenopausal women [102]. After a median follow-up of 4 years the study found no evidence of an association between CYP2D6 genotype and breast cancer recurrence. However, most patients in the study (>80%) had received chemotherapy before tamoxifen treatment, which the authors concluded may have masked any association. Premenopausal women account for approximately a third of all breast cancer patients, and more than half of them have tumors that express the ER [103]. For these patients, tamoxifen is the sole guideline endocrine treatment.

Table 1 presents the proportion of premenopausal women in each study published to date sorted by the magnitude of each study's risk ratio. We used meta-analytic methods to estimate summary hazard ratios (HRs) associating one or more reduced function CYP2D6 allele with breast cancer recurrence (graphs not presented) stratifying by menopausal status. We note summary HRs of 1.25 (95% CI: 0.91–1.71) in nine studies of predominantly postmenopausal women (0–9% premenopausal; median 0%), and of 1.54 (95% CI: 1.09–2.18) in 16 studies with at least 20% premenopausal women (20–80% premenopausal; median 43%). These findings strongly suggest that the effect of CYP2D6 inhibition and tamoxifen effectiveness may be limited to premenopausal women. Therefore, tamoxifen inhibition in this understudied group demands immediate investigation.

Transporters

In contrast to the drug metabolizing enzymes, studies on the potential impact of ABC transporters and breast cancer outcomes remain scarce. Functional expression of ABCB1 in breast tumors appears to be associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer patients, irrespective of adjuvant chemotherapy regimen [21]. In a study of 105 breast cancer patients, where approximately two-thirds of patients received tamoxifen, higher expression of ABCB1 was associated with higher grade, lymph node involvement and shorter survival [104]. By contrast, a study of 516 breast cancers (from a clinical intervention study of 1099 patients randomized to either tamoxifen and goserelin or cyclophosphamide/methotrexate/fluorouracil chemotherapy), tumor expression of ABCB1 was associated with poorer relapse-free (HR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.01–2.07) and overall survival (HR: 2.59; 95% CI: 1.31–5.12), but not among patients who received tamoxifen treatment [105]. However, this analysis may be compromised by the concomitant treatment with goserelin. Only two studies have investigated the association of genetic variation in ABC transporter proteins and breast cancer recurrence. The first study, by Kiyotani et al., examined 52 different genomic tag-SNP variants of ABC transporters (germ-line DNA) in a population of 282 postmenopausal breast cancer patients receiving tamoxifen monotherapy [66]. They reported increased rates of recurrence among carriers of the ABCC2 variant allele (rs3740065), but their estimates lacked precision (HR: 10.7; 95% CI: 1.44–78.9) and their study was prone to several biases including immortal person-time bias [93,94,106]. The ABCC2 variant allele rs3740065 is in strong linkage dis-equilibrium with the -1774delG variation in theABCC2 promoter [107]. ABCC2 has been shown to be overexpressed in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells [108]. However, the Kiyotani study reported no association between this genotype and steady-state plasma concentrations of tamoxifen or its metabolites, suggesting reduced tumor cell levels of tamoxifen and its metabolites as a result of increased ABCC2 expression. Despite this, the Kiyotani study observed no association between tamoxifen effectiveness and genetic variation in ABCB1 or ABCC1 transporters. A study by Teh et al. of 95 breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen found no association between two genetic polymorphisms in ABCB1 and breast cancer recurrence [65]. However, when they examined the combined effect of polymorphisms in ABCB1 and CYP2D6, they found an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence, but their estimates had very poor precision owing to only two exposed cases in the referent group.

As previously noted, endoxifen and 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen are substrates of the ABCB1 transporter, but the association of genetic variation in ABCB1 and tamoxifen effectiveness is not known. Clinical data are few, prone to bias and inconsistent regarding the possible impact on breast cancer outcomes. Genomic variants in the ABCC2 transporter have been associated with breast cancer outcomes in one clinical data set, while no association has been reported for the ABCC1 transporter. Transporter expression and genomic variants should, therefore, be subject to detailed analysis in planned studies.

Conclusion

Despite the large body of literature focused on Cyp2D6 inhibition and tamoxifen effectiveness, the research to date has several important methodological problems, which may have contributed to the contradictory findings. The evidence indicates that the effect of both drug-induced and/or gene-induced inhibition of CYP2D6 activity is probably null or small, or at most moderate in subjects carrying two reduced function alleles. Several issues remain unresolved, including the significance of drug transporters, the need for comprehensive genotyping and the potential for stronger associations in premenopausal women. These topics should be the focus of future research before any firm conclusion can be drawn on genotype-guided tamoxifen therapy.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.

The research to date on CYP2D6 inhibition and the effectiveness of tamoxifen has several important methodological problems and remains inconclusive.

Qualitative and quantitative review suggests that the effect of gene- or drug-induced CYP2D6 inhibition is likely to be null or small, or perhaps moderate in carriers of homozygote reduced functional alleles.

Future research should investigate the importance of the drug transporters; should comprehensively genotype all genes encoding enzymes in tamoxifen's complex metabolic pathway; and should consider investigating CYP2D6 inhibition and tamoxifen effectiveness in premenopausal women, for whom tamoxifen is the only endocrine therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute at the NIH (R01 CA118708), the Danish Cancer Society (DP06117), the Danish Medical Research Council (DOK 1158859) and the Karen Elise Jensen Foundation. The Department of Clinical Epidemiology at Aarhus University Hospital is involved in studies with funding from various companies as research grants to, and administered by, Aarhus University.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References/Websites

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: catalyst for the change to targeted therapy. Eur. J. Cancer. 2008;44(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osborne CK. Tamoxifen in the treatment of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339(22):1609–1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811263392207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burstein HJ, Prestrud AA, Seidenfeld J, et al. American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline: update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(23):3784–3796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Goldhirsch A, Ingle JN, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ. Thresholds for therapies: highlights of the St Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2009. Ann. Oncol. 2009;20(8):1319–1329. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp322. [Guidelines for clinical practice recommend tamoxifen for premenopausal women whose breast tumors express the ER, and some postmenopausal women. CYP2D6 genetic testing is not recommended in routine clinical practice.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Davies C, Godwin J, Gray J, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):771–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan VC, Collins MM, Rowsby L, Prestwich G. A monohydroxylated metabolite of tamoxifen with potent antioestrogenic activity. J. Endocrinol. 1977;75(2):305–316. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0750305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lien EA, Solheim E, Kvinnsland S, Ueland PM. Identification of 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyltamoxifen as a metabolite of tamoxifen in human bile. Cancer Res. 1988;48(8):2304–2308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adam HK, Douglas EJ, Kemp JV. The metabolism of tamoxifen in human. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1979;28(1):145–147. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stearns V, Johnson MD, Rae JM, et al. Active tamoxifen metabolite plasma concentrations after coadministration of tamoxifen and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(23):1758–1764. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coller JK, Krebsfaenger N, Klein K, et al. The influence of CYP2B6, CYP2C9 and CYP2D6 genotypes on the formation of the potent antioestrogen Z-4-hydroxy-tamoxifen in human liver. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002;54(2):157–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim YC, Desta Z, Flockhart DA, Skaar TC. Endoxifen (4-hydroxy-N-desmethyltamoxifen) has anti-estrogenic effects in breast cancer cells with potency similar to 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005;55(5):471–478. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0926-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazarus P, Blevins-Primeau AS, Zheng Y, Sun D. Potential role of UGT pharmacogenetics in cancer treatment and prevention: focus on tamoxifen. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2009;1155:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahern TP, Christensen M, Cronin-Fenton DP, et al. Functional polymorphisms in UDP-glucuronosyl transferases and recurrence in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(9):1937–1943. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Gjerde J, Hauglid M, Breilid H, et al. Effects of CYP2D6 and SULT1A1 genotypes including SULT1A1 gene copy number on tamoxifen metabolism. Ann. Oncol. 2008;19(1):56–61. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm434. [Polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes that metabolize tamoxifen affect the concentration of tamoxifen's metabolites.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Transporter Consortium. Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, et al. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9(3):215–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai Y, Varma M, Feng B, et al. Impact of drug transporter pharmacogenomics on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability – considerations for drug development. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2012;8(6):723–743. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2012.678048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leslie EM, Deeley RG, Cole SP. Multidrug resistance proteins: role of P-glycoprotein, MRP1, MRP2, and BCRP (ABCG2) in tissue defense. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005;204(3):216–237. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed K, Parissenti AM. The effect of ABCB1 genetic variants on chemotherapy response in HIV and cancer treatment. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(10):1465–1483. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amiri-Kordestani L, Basseville A, Kurdziel K, Fojo AT, Bates SE. Targeting MDR in breast and lung cancer: discriminating its potential importance from the failure of drug resistance reversal studies. Drug Resist. Updat. 2012;15(1–2):50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke R, Leonessa F, Trock B. Multidrug resistance/P-glycoprotein and breast cancer: review and meta-analysis. Semin. Oncol. 2005;32(6 Suppl. 7):S9–S15. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22••.Teft WA, Mansell SE, Kim RB. Endoxifen, the active metabolite of tamoxifen, is a substrate of the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (multidrug resistance 1). Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011;39(3):558–562. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.036160. [Highlights that tamoxifen is a substrate of P-glycoprotein.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iusuf D, Teunissen SF, Wagenaar E, Rosing H, Beijnen JH, Schinkel AH. P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) transports the primary active tamoxifen metabolites endoxifen and 4-hydroxytamoxifen and restricts their brain penetration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011;337(3):710–717. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.178301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biglia N, Torta R, Roagna R, et al. Evaluation of low-dose venlafaxine hydrochloride for the therapy of hot flushes in breast cancer survivors. Maturitas. 2005;52(1):78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry NL, Rae JM, Li L, et al. Association between CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen-induced hot flashes in a prospective cohort. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009;117(3):571–575. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0309-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demissie S, Silliman RA, Lash TL. Adjuvant tamoxifen: predictors of use, side effects, and discontinuation in older women. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19(2):322–328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9324):2131–2139. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deitcher SR, Gomes MP. The risk of venous thromboembolic disease associated with adjuvant hormone therapy for breast carcinoma: a systematic review. Cancer. 2004;101(3):439–449. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: Current status of the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project P-1 study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(22):1652–1662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swerdlow AJ, Jones ME. Tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and risk of endometrial cancer: a case–control study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(5):375–384. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crewe HK, Ellis SW, Lennard MS, Tucker GT. Variable contribution of cytochromes P450 2D6, 2C9 and 3A4 to the 4-hydroxylation of tamoxifen by human liver microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997;53(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crewe HK, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Woods FR, Haddock RE. The effect of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors on cytochrome P4502D6 (CYP2D6) activity in human liver microsomes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1992;34(3):262–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1992.tb04134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeppesen U, Gram LF, Vistisen K, Loft S, Poulsen HE, Brosen K. Dose-dependent inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 by citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996;51(1):73–78. doi: 10.1007/s002280050163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34••.Jin Y, Desta Z, Stearns V, et al. CYP2D6 genotype, antidepressant use, and tamoxifen metabolism during adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(1):30–39. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji005. [Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes that metabolize tamoxifen affect the serum concentration of tamoxifen's metabolites.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cronin-Fenton D, Lash TL, Sorensen HT. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adjuvant tamoxifen therapy: risk of breast cancer recurrence and mortality. Future Oncol. 2010;6(6):877–880. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sideras K, Ingle JN, Ames MM, et al. Coprescription of tamoxifen and medications that inhibit CYP2D6. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(16):2768–2776. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borges S, Desta Z, Jin Y, et al. Composite functional genetic and comedication CYP2D6 activity score in predicting tamoxifen drug exposure among breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010;50(4):450–458. doi: 10.1177/0091270009359182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borges S, Desta Z, Li L, et al. Quantitative effect of CYP2D6 genotype and inhibitors on tamoxifen metabolism: implication for optimization of breast cancer treatment. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006;80(1):61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahern TP, Pedersen L, Cronin-Fenton DP, Sorensen HT, Lash TL. No increase in breast cancer recurrence with concurrent use of tamoxifen and some CYP2D6-inhibiting medications. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(9):2562–2564. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lash TL, Cronin-Fenton D, Ahern TP, et al. Breast cancer recurrence risk related to concurrent use of SSRI antidepressants and tamoxifen. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(3):305–312. doi: 10.3109/02841860903575273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lash TL, Pedersen L, Cronin-Fenton D, et al. Tamoxifen's protection against breast cancer recurrence is not reduced by concurrent use of the SSRI citalopram. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;99(4):616–621. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lash TL, Cronin-Fenton D, Ahern TP, et al. CYP2D6 inhibition and breast cancer recurrence in a population-based study in Denmark. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(6):489–500. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelly CM, Juurlink DN, Gomes T, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and breast cancer mortality in women receiving tamoxifen: a population based cohort study. BMJ. 2010;340:c693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrow PK, Serna R, Broglio K, et al. Effect of CYP2D6 polymorphisms on breast cancer recurrence. Cancer. 2012;118(5):1221–1227. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wegman P, Elingarami S, Carstensen J, Stal O, Nordenskjold B, Wingren S. Genetic variants of CYP3A5, CYP2D6, SULT1A1, UGT2B15 and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(1):R7. doi: 10.1186/bcr1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wegman P, Vainikka L, Stal O, et al. Genotype of metabolic enzymes and the benefit of tamoxifen in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(3):R284–R290. doi: 10.1186/bcr993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okishiro M, Taguchi T, Jin KS, Shimazu K, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP2D6*10 and CYP2C19*2,*3 are not associated with prognosis, endometrial thickness, or bone mineral density in japanese breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen. Cancer. 2009;115(5):952–961. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oesterreich S, Hilsenbeck SH, Skaar T, et al. Correlations between genetic variants in CYP2D6 and UGT2B7 and survival in breast cancer patients treated with or without tamoxifen: results from a large cohort study.. Presented at: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, TX, USA. 8–12 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nowell SA, Ahn J, Rae JM, et al. Association of genetic variation in tamoxifen-metabolizing enzymes with overall survival and recurrence of disease in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2005;91(3):249–258. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-7751-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Regan MM, Leyland-Jones B, Bouzyk M, et al. CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer: the Breast International Group 1-98 trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(6):441–451. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abraham JE, Maranian MJ, Driver KE, et al. CYP2D6 gene variants: association with breast cancer specific survival in a cohort of breast cancer patients from the United Kingdom treated with adjuvant tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(4):R64. doi: 10.1186/bcr2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gor PP, Su HI, Gray RJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide-metabolizing enzyme polymorphisms and survival outcomes after adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(3):R26. doi: 10.1186/bcr2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rae JM, Drury S, Hayes DF, et al. CYP2D6 and UGT2B7 genotype and risk of recurrence in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(6):452–460. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park HS, Choi JY, Lee MJ, et al. Association between genetic polymorphisms of CYP2D6 and outcomes in breast cancer patients with tamoxifen treatment. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2011;26(8):1007–1013. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.8.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stingl JC, Parmar S, Huber-Wechselberger A, et al. Impact of CYP2D6*4 genotype on progression free survival in tamoxifen breast cancer treatment. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2010;26(11):2535–2542. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.518304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schroth W, Goetz MP, Hamann U, et al. Association between CYP2D6 polymorphisms and outcomes among women with early stage breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. JAMA. 2009;302(13):1429–1436. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goetz MP, Suman VJ, Hoskin TL, et al. CYP2D6 metabolism and patient outcome in the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group trial (ABCSG) 8. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19(2):500–507. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sirachainan E, Jaruhathai S, Trachu N, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphisms influence the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen in Thai breast cancer patients. Pharmgenomics Pers. Med. 2012;5:149–153. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S32160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson AM, Johnson A, Quinlan P, et al. Comprehensive CYP2D6 genotype and adherence affect outcome in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen monotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;125(1):279–287. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Newman WG, Hadfield KD, Latif A, et al. Impaired tamoxifen metabolism reduces survival in familial breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14(18):5913–5918. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bijl MJ, van Schaik RH, Lammers LA, et al. The CYP2D6*4 polymorphism affects breast cancer survival in tamoxifen users. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009;118(1):125–130. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramón y Cajal YC, Altes A, Pare L, et al. Impact of CYP2D6 polymorphisms in tamoxifen adjuvant breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;119(1):33–38. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0328-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sukasem C, Sirachainan E, Chamnanphon M, et al. Impact of CYP2D6 polymorphisms on tamoxifen responses of women with breast cancer: a microarray-based study in Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012;13(9):4549–4553. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.9.4549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu Y, Sun Y, Yao L, et al. Association between CYP2D6 *10 genotype and survival of breast cancer patients receiving tamoxifen treatment. Ann. Oncol. 2008;19(8):1423–1429. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teh LK, Mohamed NI, Salleh MZ, et al. The risk of recurrence in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen: polymorphisms of CYP2D6 and ABCB1. AAPS J. 2012;14(1):52–59. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kiyotani K, Mushiroda T, Imamura CK, et al. Significant effect of polymorphisms in CYP2D6 and ABCC2 on clinical outcomes of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(8):1287–1293. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schroth W, Antoniadou L, Fritz P, et al. Breast cancer treatment outcome with adjuvant tamoxifen relative to patient CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(33):5187–5193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kiyotani K, Mushiroda T, Sasa M, et al. Impact of CYP2D6*10 on recurrence-free survival in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(5):995–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goetz MP, Knox SK, Suman VJ, et al. The impact of cytochrome P450 2D6 metabolism in women receiving adjuvant tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2007;101(1):113–121. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70••.Schroth W, Hamann U, Fasching PA, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphisms as predictors of outcome in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen: expanded polymorphism coverage improves risk stratification. Comprehensive genotyping of the CYP2D6 gene increases the strength of the association between reduced function CYP2D6 and breast cancer recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16(17):4468–4477. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Toyama T, Yamashita H, Sugiura H, Kondo N, Iwase H, Fujii Y. No association between CYP2D6*10 genotype and survival of node-negative Japanese breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant tamoxifen treatment. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;39(10):651–656. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim H, Shin HC, Yom CK, et al. Lack of significant association between CYP2D6 polymorphisms and clinical outcomes of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy.. Presented at: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, TX, USA. 8–12 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lash TL. Association between CYP2D6 polymorphisms and breast cancer outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303(6):516. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Damodaran SE, Pradhan SC, Umamaheswaran G, Kadambari D, Reddy KS, Adithan C. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP2D6 increase the risk for recurrence of breast cancer in patients receiving tamoxifen as an adjuvant therapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2012;70(1):75–81. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1891-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chubak J, Buist DS, Boudreau DM, Rossing MA, Lumley T, Weiss NS. Breast cancer recurrence risk in relation to antidepressant use after diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008;112(1):123–132. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9828-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Azoulay L, Dell'aniello S, Huiart L, du Fort GG, Suissa S. Concurrent use of tamoxifen with CYP2D6 inhibitors and the risk of breast cancer recurrence. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;126(3):695–703. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1162-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Validity in epidemiologic studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, editors. Modern Epidemiology. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; PA, USA: 2008. pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aubert RE, Stanek EJ, Yao J, et al. Risk of breast cancer recurrence in women initiating tamoxifen with CYP2D6 inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:18S. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dusetzina SB, Alexander GC, Freedman RA, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Trends in co-prescribing of antidepressants and tamoxifen among women with breast cancer, 2004–2010. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013;137(1):285–296. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2330-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Binkhorst L, Mathijssen RH, van Herk-Sukel MP, et al. Unjustified prescribing of CYP2D6 inhibiting SSRIs in women treated with tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013;139(3):923–929. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2585-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stanton V., Jr Re: CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer: the Breast International Group 1-98 trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(16):1265–1266. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs305. author reply 1266–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kelly CM, Pritchard KI. CYP2D6 genotype as a marker for benefit of adjuvant tamoxifen in postmenopausal women: lessons learned. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(6):427–428. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pharoah PD, Abraham J, Caldas C. Re: CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer: the Breast International Group 1-98 trial and Re: CYP2D6 and UGT2B7 genotype and risk of recurrence in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(16):1263–1264. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs312. author reply 1266–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakamura Y, Ratain MJ, Cox NJ, McLeod HL, Kroetz DL, Flockhart DA. Re: CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer: the Breast International Group 1-98 trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(16):1264. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs304. author reply 1266–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ellsworth RE, Ellsworth DL, Lubert SM, Hooke J, Somiari RI, Shriver CD. High-throughput loss of heterozygosity mapping in 26 commonly deleted regions in breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(9):915–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hirano A, Emi M, Tsuneizumi M, et al. Allelic losses of loci at 3p25.1, 8p22, 13q12, 17p13.3, and 22q13 correlate with postoperative recurrence in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7(4):876–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Benetkiewicz M, Piotrowski A, Diaz De Stahl T, et al. Chromosome 22 array-CGH profiling of breast cancer delimited minimal common regions of genomic imbalances and revealed frequent intra-tumoral genetic heterogeneity. Int. J. Oncol. 2006;29(4):935–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Day IN. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium testing of biological ascertainment for mendelian randomization studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009;169(4):505–514. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salanti G, Amountza G, Ntzani EE, Ioannidis JP. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in genetic association studies: an empirical evaluation of reporting, deviations, and power. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;13(7):840–848. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Trikalinos TA, Salanti G, Khoury MJ, Ioannidis JP. Impact of violations and deviations in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium on postulated gene-disease associations. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006;163(4):300–309. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ahern TP, Christensen M, Cronin-Fenton D, et al. Concordance of metabolic enzyme genotypes assayed from paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed breast tumors and normal lymphatic tissue. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010;2:241–246. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S13811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rae JM, Cordero KE, Scheys JO, Lippman ME, Flockhart DA, Johnson MD. Genotyping for polymorphic drug metabolizing enzymes from paraffin-embedded and immunohistochemically stained tumor samples. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(8):501–507. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93••.Lash TL, Lien EA, Sorensen HT, Hamilton-Dutoit S. Genotype-guided tamoxifen therapy: time to pause for reflection? Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(8):825–833. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70030-0. [Gene–drug and drug–drug interactions affect the concentration profile of tamoxifen's metabolites but these changes may have little clinical impact on tamoxifen's effectiveness. The clinical epidemiology to date is widely heterogeneous, without adequate explanation, and with an average association near the null.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lash TL, Ahern TP, Cronin-Fenton D, Garne JP, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Sorensen HT. Comment on ‘impact of CYP2D6*10 on recurrence-free survival in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant tamoxifen therapy’. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(8):1706–1707. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95••.Dunn BK, Greene MH, Kelley JM, et al. Novel pathway analysis of genomic polymorphism-cancer risk interaction in the breast cancer prevention trial. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 2010;1(4):332–349. [Analysis of the complete tamoxifen metabolic pathway will give insights into the association between tamoxifen metabolism and breast cancer outcomes.] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lash TL, Ahern TP. Bias analysis to guide new data collection. Int. J. Biostat. 2012 doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1345. doi:10.2202/1557,4679.1345 Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jordan VC. Metabolites of tamoxifen in animals and man: identification, pharmacology, and significance. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1982;2(2):123–138. doi: 10.1007/BF01806449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Baurley JW, Conti DV, Gauderman WJ, Thomas DC. Discovery of complex pathways from observational data. Stat. Med. 2010;29(19):1998–2011. doi: 10.1002/sim.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jordan VC, Dowse LJ. Tamoxifen as an anti-tumour agent: effect on oestrogen binding. J. Endocrinol. 1976;68(02):297–303. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0680297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Johnson MD, Zuo H, Lee KH, et al. Pharmacological characterization of 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl tamoxifen, a novel active metabolite of tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2004;85(2):151–159. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025406.31193.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sherman BM, Chapler FK, Crickard K, Wycoff D. Endocrine consequences of continuous antiestrogen therapy with tamoxifen in premenopausal women. J. Clin. Invest. 1979;64(2):398–404. doi: 10.1172/JCI109475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Saladores P, Schroth W, Eccles D, Tapper W, Gerty S, Brauch H. CYP2D6 polymorphisms are not associated with tamoxifen outcome in premenopausal women with ER positive breast cancer of the POSH cohort. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2012;72(8 Suppl. 1):2671. [Google Scholar]

- 103.American Cancer Society . Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2009–2010. American Cancer Society, Inc.; Atlanta, GA, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Surowiak P, Materna V, Matkowski R, et al. Relationship between the expression of cyclooxygenase 2 and MDR1/P-glycoprotein in invasive breast cancers and their prognostic significance. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(5):R862–R870. doi: 10.1186/bcr1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Filipits M, Pohl G, Rudas M, et al. Clinical role of multidrug resistance protein 1 expression in chemotherapy resistance in early-stage breast cancer: the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(6):1161–1168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lash TL, Cole SR. Immortal person-time in studies of cancer outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(23):e55–e56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sai K, Saito Y, Itoda M, et al. Genetic variations and haplotypes of ABCC2 encoding MRP2 in a Japanese population. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2008;23(2):139–147. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.23.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Choi HK, Yang JW, Roh SH, Han CY, Kang KW. Induction of multidrug resistance associated protein 2 in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2007;14(2):293–303. doi: 10.1677/ERC-06-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Siegelmann-Danieli N, Kurnik D, Lomnicky Y, et al. Potent CYP2D6 inhibiting drugs do not increase relapse rate in early breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;125(2):505–510. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dezentjé VO, van Blijderveen NJ, Gelderblom H, et al. Effect of concomitant CYP2D6 inhibitor use and tamoxifen adherence on breast cancer recurrence in early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(14):2423–2429. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lehmann D, Nelsen J, Ramanath V, Newman N, Duggan D, Smith A. Lack of attenuation in the antitumor effect of tamoxifen by chronic CYP isoform inhibition. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;44(8):861–865. doi: 10.1177/0091270004266618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.The Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database. www.cypalleles.ki.se.

- 202.National Cancer Institure Tamoxifen citrate in treating patients with metastatic or recurrent breast cancer. www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search/view?cdrid=672523&version=healthprofessional.

- 203.NCCN practice guidelines in oncology, breast cancer – v.2.2011. Invasive breast cancer, adjuvant endocrine therapy. 2010 www.nccn.org.