Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the impact of the phophodiesterase-4 inhibition (PD-4-I) with rolipram on hepatic integrity in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced hyperinflammation.

Materials and Methods:

Liver microcirculation in rats was obtained using intravital microscopy. Macrohemodynamic parameters, blood assays, and organs were harvested to determine organ function and injury. Hyperinflammation was induced by LPS and PD-4-I rolipram was administered intravenously one hour after LPS application. Cell viability of HepG2 cells was measured by EZ4U-kit based on the dye XTT. Experiments were carried out assessing the influence of different concentrations of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and LPS with or without PD-4-I.

Results:

Untreated LPS-induced rats showed significantly decreased liver microcirculation and increased hepatic cell death, whereas LPS + PD-4-I treatment could improve hepatic volumetric flow and cell death to control level whithout influencing the inflammatory impact. In HepG2 cells TNF-α and LPS significantly reduced cell viability. Coincubation with PD-4-I increased HepG2 viability to control levels. The heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) pathway did not induce the protective effect of PD-4-I.

Conclusion:

Intravenous PD-4-I treatment was effective in improving hepatic microcirculation and hepatic integrity, while it had a direct protective effect on HepG2 viability during inflammation.

Keywords: Acute liver failure, endotoxemia, phosphodiesterase, rolipram, sepsis

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis with consecutive multiple organ failure (MOF) remains an unsolved therapeutic challenge in critical care medicine. Between 20 and 25% of patients develop acute liver failure (ALF) in the course of sepsis,[1] with mortality rates ranging from 40 to 50% depending on the etiology.[2] Therefore, manifestation of ALF represents a predictor for poor outcome in critically ill patients.[3] One of the crucial pathophysiological features leading to MOF during sepsis is microcirculatory dysfunction, which is also evident in the liver.[4] A pivotal regulator of hepatic microcirculation is the enzyme heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), which catalyzes the reaction of heme into carbon monoxide, biliverdin and Fe2+ leading to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-mediated vasodilation.[5] HO-1 is upregulated by hemorrhage, endotoxemia, and shock, and is therefore regarded as a rescue mechanism for liver microcirculation.[6,7,8] Additionally, human livers transplanted with initially higher HO-1 activity featured reduced reperfusion injury and exhibited better organ function post transplantation.[9]

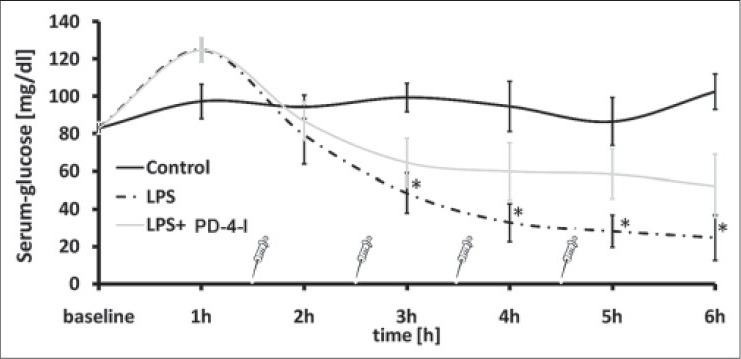

In our previous studies, systemic application of phosphodiesterase-4-inhibitors (PD-4-I) effectively attenuated intestinal microcirculatory failure by preventing microvascular leakage.[10,11] This led to improved metabolism and increased overall survival of the animal. An unpublished observation in these experiments was that PD-4-I application resulted in a significantly higher serum-glucose level, which led to the assumption that PD-4-I may also have protective effects on inflammation-induced liver dysfunction [for results see supplemental figure 1].[12,13] In this context, Coimbra et al. showed that nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibition is capable of reducing hepatocellular injury in acute endotoxemia. This effect was explained by suppression of interleukin-6 and TNF-α levels, while direct effects on hepatic microcirculation remained unexplored.[14]

Supplemental Figure 1.

Glucose levels from the experiment [11]. PD-4-I rolipram was able to stabilize plasma glucose levels over six hours in hyperinflammation. (P<0.05 vs. control)

The aim of the present study was to determine the effect of systemic treatment with PD-4-I on hepatocellular integrity in vitro and in vivo animal model of systemic hyperinflammation. We tested whether PD-4-I induced beneficial effects on hepatic microcirculation and whether such effects may be explained by the modulation of cytokine response and/or its influence on the HO-1 system in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval

Upon Animal Care Committee approval (District of Unterfranken, Germany) 34 male Sprague Dawley rats (mean weight: 0.332 ± 0.002 kg) were obtained from Harlan Winkelmann, NM Horst, Netherlands. Animals were kept conforming to the National Institute of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at a 12-hour day and night cycle. Standard chow and tap water were provided ad libitum.

Surgical procedure

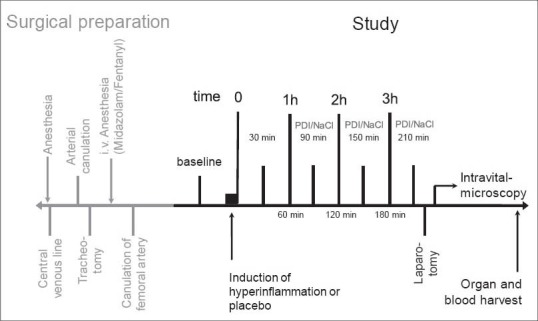

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (Forene, Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) and N2O and then provided with central venous and arterial lines and tracheostomy for mechanical ventilation (FiO2 0.28) according to PaCO2 (35-45 mmHg) as previously described.[10,15] Anesthesia was adjusted to 0.7% isoflurane with a continuous intravenous application of fentanyl and midazolam, discontinuing the nitrous oxide (for details see).[10,15,16] A thermo-catheter was applied into the femoral artery (MLT1402 T-type Ultra Fast Thermocouple, ADInstruments, Spechbach, Germany) to determine cardiac output (CO) using thermodilution methods with PowerLab software (ADInstruments, Spechbach, Germany). [For overview please see Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Design of intravital microscopy study of the liver: After animals were instrumented for intensive care set-up, 3 groups were randomized: 1. Control group without hyperinflammation or treatment, 2. LPS group with hyperinflammation and placebo therapy, and 3. LPS + PD-4-I group with hyperinflammation and rolipram therapy (each n = 5-6). Laparotomy and intravital microscopy were performed; afterwards organs and blood were harvested

Macrohemodynamics

Hemodynamic parameters for rodents were calculated as previously described in detail for cardiac index (CI, [ml/min/kgBW]), stroke volume-index (SVI, [ml/beat/kgBW]), total peripheral resistance-index (TPRI, [mmHg/ml/min/kgBW]), arterial oxygen content (CaO2, [ml/dl]), Oxygen delivery-index (DO2-I, [ml/min/kgBW]).

Experimental setup

Rats were randomized into three groups: Control (n = 5), LPS (n = 6) and LPS + PD-4-I (n = 5). Not being aware of applying verum or placebo, the study was blinded for the investigator. Throughout the experiment the body temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C. Control received a 0.5 ml intravenous bolus of NaCl as placebo, whereas lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (from E. coli O111:B4, Sigma Aldrich, Deisenhof, Germany) was applied, body weight (BW)-adapted, intravenously at a concentration of 2.5 mg/kg to the LPS and LPS + PD-4-I groups. Macrohemodynamics (mean arterial pressure [MAP], heart rate [HR], central venous pressure [CVP], and cardiac output [CO]) were electronically recorded at baseline and every 30 minutes. Every hour 0.2 ml blood was withdrawn from the arterial line to perform blood gas analysis. Treatment with three boli of rolipram i.v. (PD-4-I, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, [Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany, 300 μg/100 gBW]) were executed to the LPS + PD-4-I group at one-and-a-half, two-and-a-half, and three-and-a-half hours post induction of endotoxemia. Animals in the LPS group were treated with 0.2 ml NaCl placebo accordingly. For hemodynamic stabilization, fluid resuscitation with 1 ml balanced crystalloid solution i.v. (Sterofundin® Iso, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) was applied when MAP dropped below 60 mmHg. At the three-and-a-half hour subcostal transverse laparotomy was performed and hepatogastric ligaments were carefully dissected to mobilize the left liver lobe.

Intravital microscopy

For liver microcirculation intravital microscopy was performed as previously described.[15,16,17] The animals were placed in a 110° left position under the microscope (Axiovert 200, Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). The upper surface of the liver was continuously super-perfused with 37°C NaCl. Blood perfusion within individual sinusoids was studied with contrast enhancement by fluorescein isothiocyanate-albumin (5 μg/100 g intravenously, Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) and fluorescein sodium (1 μg/g intravenously, Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) i.v. as described previously.[15] Microcirculation was then examined at 450-490 nm excitation wavelengths and a 520 nm bandpass filter, epi-illuminating the liver surface using a 100-W mercury lamp. Sequences and pictures were electronically recorded, captured, and stored in MetaMorph online software (MetaMorph V6.0r4, Universal Imaging Corporation, USA) for subsequent offline analysis.

Examination of functional sinusoidal density (FSD) included at least 10 sequences per animal at 100× magnification, followed by focussing at least 6 randomly selected sinusoids at 200× magnification for measurement of volumetric flow and sinusoidal diameter.

Dead or dying cells were quantified by propidium iodide (PI; propidiumiodide >94% HPLC, Sigma, Taufkirchen, Deutschland; dissolved in H2O) vital dye applied at 0.025 mg/100 gBW. Filter set with excitation wavelengths of 510-560 nm and an emission barrier filter >590 nm were used to capture at least 10 pictures from randomly selected hepatic areas at 200×.[18]

For characterization of rolling or sticking leukocyte, rhodamine (Rhodamin 6G 95%, Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany; dissolved in NaCl) was injected intravenously at 0.1 mg/100 gBW.[19] Blood samples were analysed by the Division of Laboratory Medicine, University of Würzburg, Germany. Additionally, blood samples were centrifuged (3400 g for 10 minutes at 4°C). The remaining plasma was stored at −80°C for measurement of cytokine levels while the right liver lobe was harvested and kept in formaldehyde 3.5% at room temperature (RT) for 24 hours for histopathological examination, while another set of liver specimen was frozen at −80°C for RNA and protein analysis.

Evaluation of microcirculation

Offline analysis with MetaMorph software (MetaMorph offline V6.1r4, Universal Imaging Corporation, USA) was performed by blinded investigators. For functional sinusoidal density (FSD) the number of continuously (CPS), intermittently (IPS), and non-perfused sinusoids (NPS) were counted per field of view (0.4 mm2). Red blood cell (RBC) velocity [μm/sec] and sinusoidal diameter [μm] were calculated using MetaMorph. Volumetric flow [pl/sec] was calculated as described.[10] PI-labeled cells were counted per field of view (0.1 mm2) and leukocytes characterized as either “rolling” or “sticking” were counted.

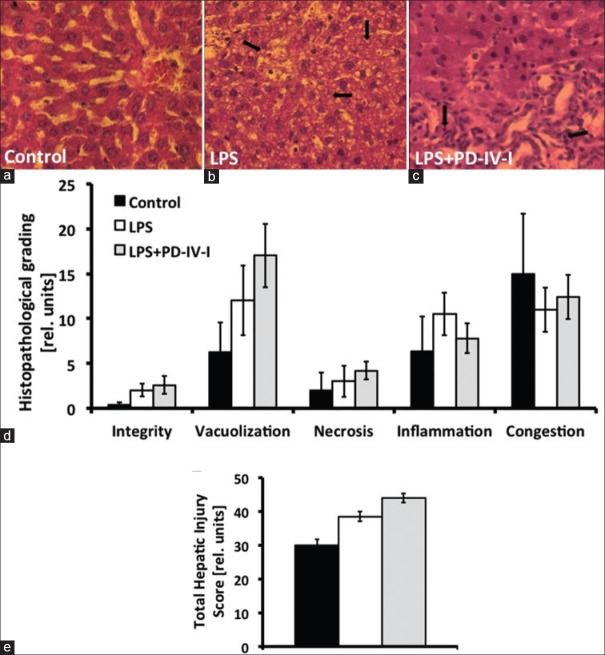

Histopathological examination

The morphological alterations of the liver were analyzed semi-quantitatively by a blinded investigator, where 0 was given when no alterations were found, 1 for mild alterations, 2 for medium alterations, and 3 for severe alterations. Criteria for histopathological assessment were hepatic integrity, cell necrosis, vacuolization, inflammation, and congestion. Mean values from the scores of the latter criteria were taken together as total hepatic injury score. For every category 25 fields of view per slide (400× magnification) were randomly selected and graded.

Cytokine levels were measured as described previously.[15] Briefly Luminex® assay (‘Rat 10-Plex’ Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used according to manufacturer's instructions. Analyses were done in triplicate with a Luminex® 100 instrument (Luminex Corporation, Austin, Texas, USA).

Markers of liver function

Alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), cholinesterase (CHE), albumin, international normalized ratio (INR), and blood count were routinely measured by the Division of Laboratory Medicine, University of Würzburg, Germany.

HO-1 expression

In brief, 18 Sprague Dawley rats were invasively hemodynamically monitored as described above. Randomization was performed into three groups: Control (n = 6), LPS (n = 6) and LPS + PD-4-I (n = 6). No intravital microscopy of the liver was performed. LPS + PD-4-I animals were treated with four boli of rolipram (300 μg/100 gBW i.v.) at one-and-a-half, two-and-a-half, three-and-a-half, and four-and-a-half hours. Fluid resuscitation was carried out in analogy to the above-mentioned experiments. After six hours, animals were sacrificed and liver samples were frozen at -80°C for measurements of protein and RNA expression.

To examine mRNA expression of HO-1 in the liver specimen taken as above, quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used. Total RNA was extracted using the commercially available NucleoSpin RNA II-Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions. One μg of resulting RNA was transcribed to cDNA with High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA). Using absolute QPCR ROX Mix (Thermo Scientific Inc., USA) and corresponding probes from Life Technologies (Darmstadt, Germany) qRT-PCR was carried out for analysis of gene expression levels of HO-1 (Rn01536933_ml), GAPDH (Rn01775763), 18S rRNA (4352930-0810022), and β-Actin (Rn00667869). Relative mRNA levels of HO-1 were determined by normalization to endogenous controls GAPDH, 18S rRNA, and β-Actin using the ddCt method.

Heme oxygenase 1 protein expression was measured in duplicate with common Western Blot technique (HO-1 antibody, Abcam, Great Britain), as described previously.[20]

Cell culture

Hepatoma cell line (HepG2) was obtained from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ), Germany and grown in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were seeded onto microtiter plates (96-wells) at 4.4 × 103 cells/0.5 cm2 well and incubated for four days. Every two days, the medium was changed and on day five the medium was removed and cells were incubated with the following substances at different concentrations: LPS (3.125-50 μg/ml), TNF-α (5-40 ng/ml), rolipram (5-40 μM), LPS + rolipram, and TNF-α + rolipram. As a reference, each plate contained cells incubated with control solution consisting of the medium with maximum volume of solvents contained in the test reagents (H2O or H2O plus dimethyl sulfoxide). After 21 hours of incubation time, cell viability was determined with EZ4U-tests (dye XTT, Biomedica GmbH and Co. KG, Austria) carried out as previously described.[21,22] In a subsequent set of experiments, cell viability was assessed for HepG2 cells after HO-1 inhibition by chromium mesoporphyrin (CrMP; Frontier Scientific, Utah, USA) in the inflammatory milieu of TNF-α, LPS, and rolipram alone as described above.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analyses, SPSS 20.0 (IBM, USA) software was used. Data were examined upon normal distribution and homogeneity of variance and were accordingly analyzed. For parametric data, one–way ANOVA following post-hoc Duncan testing was used, whereas non-parametric data were analyzed utilizing Kruskal-Wallis testing with consecutive Mann-Whitney U tests and Bonferroni correction. Two-group-comparisons were performed with Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. A level of significance of P ≤ 0.05 was assumed; values expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Macrohemodynamic changes

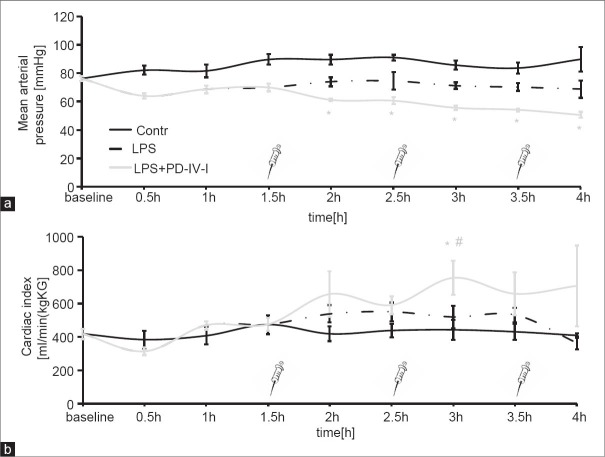

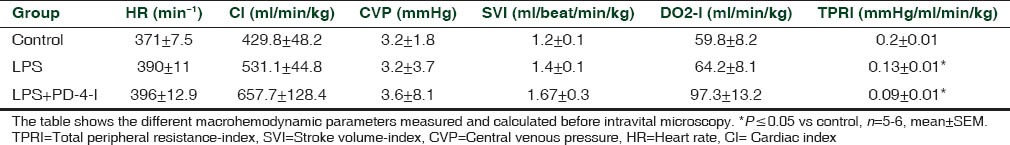

Lipopolysaccharide application resulted in severe systemic hyperinflammation in all animals as has already been reported in great detail previously.[10] MAP was reduced following LPS application and was significantly reduced in the PD-4-I group after application of PD-4-I [Figure 2a]. CI was significantly increased in the LPS + PD-4-I animals only at three hours [Figure 2b]. HR, CVP, SVI, and DO2-I remained at similar levels when LPS and LPS + PD-4-I groups were compared [Table 1].

Figure 2.

MAP and CI in the course of the experiment: (a) Mean arterial pressure is significantly reduced after the first bolus of PD-4-I (syringe) and through out the rest of the experiment. (b) Cardiac index is significantly elevated at three hours in the LPS/PD-4-I group compared to control and LPS groups. (*P≤0.05 vs Control, #P≤0.05 vs. LPS, n=5-6, mean ± SEM)

Table 1.

Macrohemodynamic parameters

Effects on the microcirculation

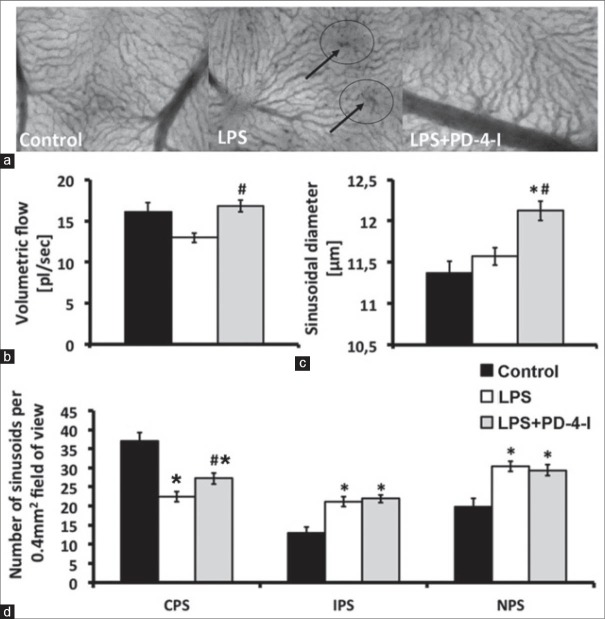

Lipopolysaccharide significantly decreased sinusoidal volumetric flow (12.94 ± 0.6 μm3/ms), whereas PD-4-I (16.8 ± 0.7 μm3/ms) stabilized hepatic microcirculation to control levels (16.26 ± 1.0 μm3/ms; Figure 3b). Additionally, rolipram significantly increased sinusoidal diameter (11.4 ± 0.1 control; 11.57 ± 0.1 LPS; 12.1 ± 0.1 LPS + PD-4-I [μm]) and functional sinusoidal density (37.1 ± 2.1 control; 21.8 ± 1.3 LPS; 27.2 ± 1.5 LPS + PD-4-I [perfused sinusoids/0.4 mm2]) illustrating a protective effect for sinusoidal microhemodynamics in endotoxemia [Figure 3a and c and d].

Figure 3.

Microhemodynamics: (a) Sinusoidal microcirculation, arrows indicate areas of non-perfused sinusoids (b) Volumetric flow in perfused sinusoids, revealing significantly higher volumetric flow in PD-4-I treated animals (c) Sinusoidal diameters show significantly dilated sinusoids in the LPS + PD-4-I compared to control and LPS (d) Number of continuously (CPS), intermittently (IPS), and non-perfused sinusoids (NPS) demonstrating a significantly higher count of CPS in PD-4-I treated animals compared to the LPS group. (*vs. Control, #vs. LPS, §vs. LPS + PD-4-I, n = 5-6, P ≤ 0.05, mean ± SEM)

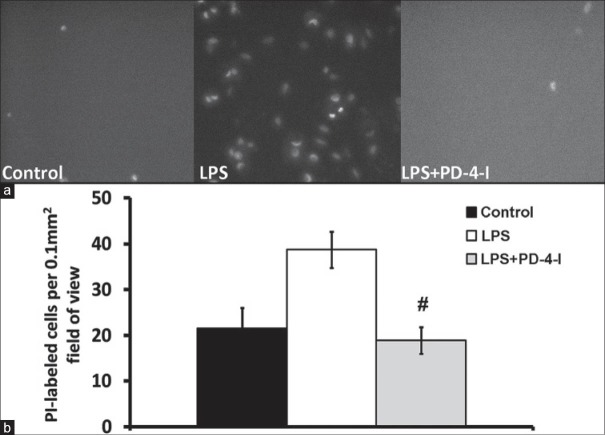

Effects on liver integrity

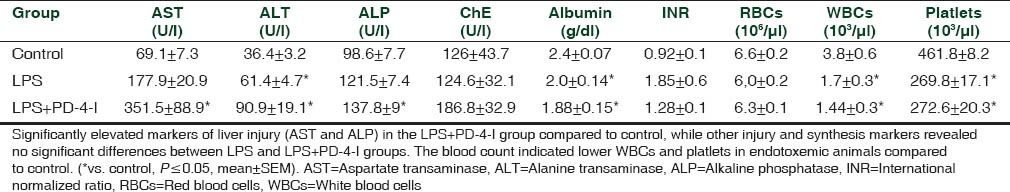

In vivo fluorescent microscopy revealed an increased rate of hepatic cell death by LPS, whereas rolipram attenuated LPS-induced cell death in the in vivo fluorescent-microscopy [Figure 4]. Markers of liver injury were compared in order to prove liver injury following LPS treatment of animals. Serum glucose was significantly reduced in LPS animals. AST, ALP, and ALT were augmented compared to controls while liver synthesis parameter (INR, CHE, and albumin) were unchanged [Table 2]. In the LPS + PD-4-I group AST and ALP were even augmented compared to LPS treatment alone, while serum glucose levels reached control levels following PD-4-I treatments. In histopathological examination no significant differences were obvious [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

PI-labeled cells in intravital microscopy: (a) shows exemplary fluorence microscopy images of PI-labeled dead cells (b) shows the counted PI-labeled cells per field of view. Control and LPS + PD-4-I groups exhibited significantly less dead or dying cells per field of view. (#vs. LPS; n = 5-6, P ≤ 0.05, mean ± SEM)

Table 2.

Markers of liver-function and bloodcount

Figure 5.

Exemplary microscopic anatomy of the liver and hepatic injury scores: (a) control group, (b) LPS group with marked areas of vacuolization, (c) LPS + PD-4-I group with marked areas of inflammation. Graphs: (d) and (e) Total hepatic injury score (THIS), revealing no significant differences among the different groups. (n=5-6, P≤0.05, mean±SEM)

Immunmodulatory effects by PD-4-I

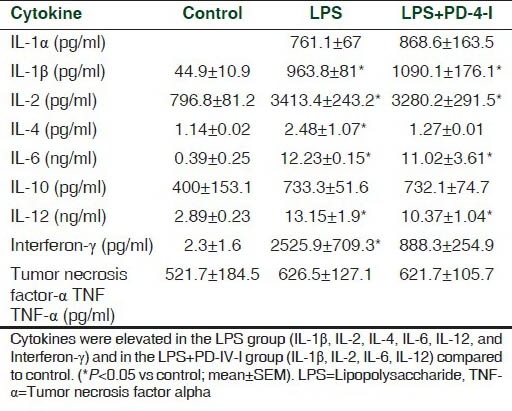

No significant differences of hepatic rolling or sticking leucocytes in vivo between LPS or LPS + PD-4-I treated animals were detected. Plasma levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, TNF-α, Interferon-g, and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) revealed no differences when LPS and LPS + PD-4-I were compared, but showed a hyperinflammation-cytokine storm when compared to control (see supplemental material). Thus PD-4-I treatment did not significantly alter cytokine production and is therefore unlikely to explain rolipram-mediated improvement of hepatic microcirculation.

Supplemental Table 1.

Plasma cytokine levels at the end of experiments

HO-1 expression in vivo

Finally we tested HO-1 mRNA expression and protein content in the liver. We observed a trend towards a higher mRNA content of HO-1 in the LPS + PD-4-I-group compared to the LPS group. Therefore, six hours after LPS incubation, HO-1 protein expression was investigated revealing a reduced HO-1 protein level in the LPS group whereas it was increased in the PD-4-I group, but did not reach significance (data not shown).

PD-4-I application and HO-1 inhibition blocked inflammation-induced loss of cell viability in vitro

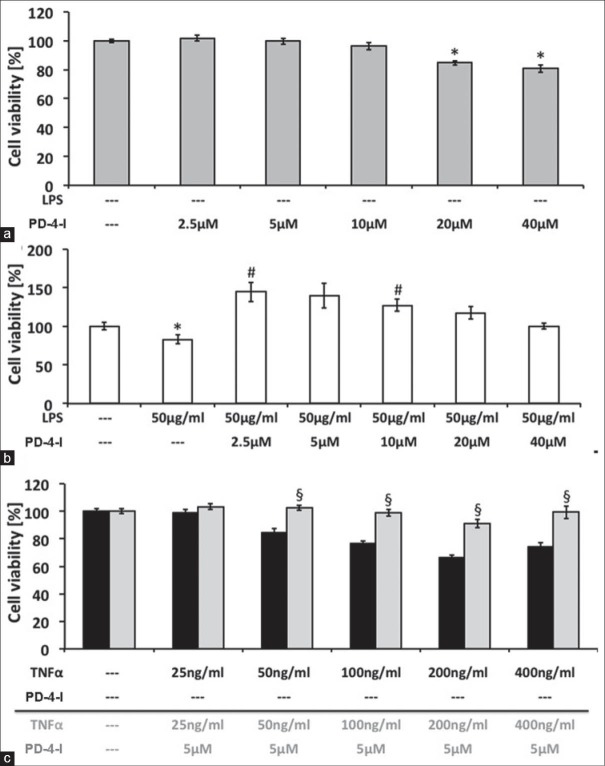

Hepatoma cell line, HepG2, cell culture was used as an in vitro model of hepatocytes to test our hypothesis of direct effects of PD-4-I on hepatocytes. First we tested the influence of PD-4-I at different doses on cell viability using the EZ4U-tests. Doses of rolipram at 2.5-10 μM did not affect cell viability while higher doses of 20-40 μM rolipram significantly reduced cell viability [Figure 6]. Application of 50μg LPS significantly reduced cell viablility and coincubation with PD-4-I resulted in significantly augmented cell viability. Interestingly, this was also observed when higher doses of rolipram (20-40 μM) were used. Proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α (25-400 ng/ml) led to significantly decreased cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner. Because 5 μM rolipram showed no derangements to HepG2 cells, the coincubation with TNF-α + PD-4-I 5μM was investigated and revealed improved cell viability to control levels.

Figure 6.

HepG2 cell culture: Cell viability of PD-4-I-incubated cells (A) and in presence of 50 μg/ml LPS, showing a compromised viability with 50 ng/ml LPS and a cytoprotective effect of 2.5 μM and 10 μM PD-4-I. (C) Cell viability of different concentrations of TNF-α with and without 5μM PD-4-I, revealing cytoprotective effects of PD-4-I incubation at 50-400 ng/ml. (*vs. 0%, #vs. 50 μg/ml LPS; §vs. corresponding TNF-α-only incubated cells, n = 32-64, P≤ 0.05, mean ± SEM)

To evaluate the influence of HO-1 on the protective properties of PD-IV inhibition, CrMP, an antimetabolite to block the heme oxygenase enzyme, was used. CrMP (1-50 μM) showed no influence on HepG2 viability (data not shown), but HO inhibition with CrMP reduced cell viability after TNF-α treatment in a dose-dependent manner. However, cells treated with TNF-α + PD-4-I and 50 μM CrMP exhibited significantly improved cell viability when compared with cells treated with TNF-α and 50 μM CrMP alone [Supplemental Figure 2].

Supplemental Figure 2.

HO-1 block with CrMP was not able to attenuate PD-4-I viability improvement of HepG2 cells. (*P<0.05 vs control, #P<0.05 vs. TNF-α + 50μM CrMP)

DISCUSSION

The origin of the present study was the observation of a perpetuated serum-glucose level by PD-4-I treatment in hyperinflammation shock in rats and the hypothesis of liver protection by PD-4-I treatment (see supplemental material).[10] Inflammatory conditions like endotoxemia cause mediators of innate immunity like human neutrophil α-defensin to effectively suppress gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis by insulin-like signaling pathways.[23] Catabolic glucose metabolism is mediated through insulin opponents, like glucagon and catecholamines, by cyclic adenosine monophasphate (cAMP) signaling in the liver,[24] which is likely to be induced by PD-4-I treatment. In vitro studies in hepatocytes showed that out of all phosphodiesterases, PD-4 contributes with 84% of all cytosolic phosphodiesterase-activity.[25] Contradicting our observations, roflumilast, a recently approved PD-4-I for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, revealed capabilities of lowering glycated hemoglobin levels in diabetic patients.[26] Additionally, PD-4-I proved to stimulate secretion of glucose-like-peptide-1 in pancreatic islets, lowering glucose concentration in diabetic mice.[27] However, the results presented in our survey show a protective effect of PD-4 inhibition on the systemic hypoglycemia observed in animals with LPS induced hyperinflammation.

Following PD-4-I application, a significant drop in MAP was observed. As the cardiac index was maintained and even partially increased. Systemic vasodilation might explain the changes in MAP, as PD-4-I showed significantly reduced TPRI beginning at two hours, but only at four hours the rolipram-treated animals exhibited significantly reduced TPRI compared to LPS alone. These results are in contrast to our previous results, which led to the hypotheses that PD-4-I has a small therapeutic index in hyperinflammation. Despite MAP drop, microcirculation was perpetuated by PD-4-I treatment. Improved microcirculation, with increased density of continuous perfused sinusoids in intravital microscopy, combined with higher volumetric flow sustains the theory of better organ perfusion. Enhanced hepatic perfusion might play a pivotal role in increased cell survival and reduced PI-labeled cells displayed by intravital microscopy. Certainly, liver tissue not only consists of hepatocytes, but also of sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells (KCs), and stellate cells. In our study it remains unclear whether a singular protection of hepatocytes was achieved or if microscopic observations of cell survival can also be attributed to other cell types. It is well known, that KCs contribute to liver protection in acetaminophen-induced ALF[28] and to endothelial protection during sepsis.[29] However, hepatocytes make up the dominant type of cells in the liver and are crucial to hepatic function, hence presenting an important target for direct liver protection. In our in vitro experiments, hepatocytes exhibited compromized viability due to LPS or TNF-α incubation, but rescue effects were achieved utilizing co-incubation with PD-4-I. This observation points towards direct protective effects of PD-4-I on hepatocytes. Contributing factor besides PD-4-I might be pH-mediated autoregulation, as the PD-4-I group revealed a significantly reduced pH. Carbon monoxide (CO), produced by induced HO–1 is another potent vasodilator. Ample evidence of HO-1 as a key regulator of hepatic microcirculation exists, while other positive effects (like reduced apoptosis) in hepatocellular injury are mediated by HO-1 products.[30] Therefore we examined HO-1 expression at the mRNA and protein levels in the liver specimen. In LPS + PD-4-I treated animals, only a trend towards upregulated HO-1 mRNA was detectable. Additionally, HO-1 protein in vivo and HO-1 blockage in vitro showed no significant difference between the groups according to protection via PD-4 inhibition. Therefore we were able to show, to our best knowledge for the first time, that PD-4-I exerts its hepatoprotective effects during systemic inflammation, independent of the HO enzyme system. To determine direct protective effects of PD-4-I on hepatocytes, HepG2 cell culture was used. Under inflammatory conditions (LPS or TNF-α incubation), PD-4-I co-treatment was able to increase cell viability pointing towards direct protective effects in a dose-dependent manner.

Blood markers of liver damage showed elevated AST and ALP in PD-4-I-treated animals, in contrast to a more intact liver integrity observed in intravital microscopy. We hypothesize that due to improved microcirculation, an increased “wash out” of liver enzymes took place, as described in studies of reperfusion injury.[31] Furthermore, it is questionable, whether a short time span of four-hour systemic inflammation represents reliable evaluation of organ damage by liver enzymes or histopathology. An essential mechanism, which has previously been associated with liver protection in systemic inflammation by phosphodisterase inhibition, was the suppression of immune response.[14] PD-4-I treatment is capable of subduing immune response,[13] and, therefore, is used for the treatment of inflammatory pulmonary diseases. Stating this, our study tried to determine the extent of local leukocyte-endothelium interaction by in vivo imaging in the liver as well as by measuring cytokine levels post mortem. We were unable to find a significant immune modulating effect of PD-4-I after LPS application, and therefore hypothesize that mechanisms other than immune suppression are responsible for our above mentioned observations.

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated in our experiments a liver protective therapeutic effect of systemic PD-4-I treatment in acute endotoxaemia in vivo. We were able to show that PD-4-I perpetuated liver microcirculation despite compromised macrohemodynamics and showed no influence on the systemic or local hepatic inflammatory response. In vitro observed effects of PD-4-I might directly play a crucial role of improved hepatocellular viability, which seems to be independent of HO-1 expression. Nevertheless, continuing studies are necessary to determine clinical applicability of PD-4-I, especially regarding adverse effects and long-term survival benefits in polymicrobial sepsis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Ms. Veronica Heimbach and Anja Neuhoff for the skillful technical assistance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakker J, Grover R, McLuckie A, Holzapfel L, Andersson J, Lodato R, et al. Glaxo Wellcome International Septic Shock Study Group. Administration of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-methyl-L-arginine hydrochloride (546C88) by intravenous infusion for up to 72 hours can promote the resolution of shock in patients with severe sepsis: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study (study no-144-002) Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1–12. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000105118.66983.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernal W, Auzinger G, Dhawan A, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2010;376:190–201. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer L, Jordan B, Druml W, Bauer P, Metnitz PG Austrian Epidemiologic Study on Intensive Care, ASDI Study Group. Incidence and prognosis of early hepatic dysfunction in critically ill patients--a prospective multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1099–104. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259462.97164.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanoore Edul VS, Dubin A, Ince C. The microcirculation as a therapeutic target in the treatment of sepsis and shock. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:558–68. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1287864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. The enzymatic conversion of heme to bilirubin by microsomal heme oxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;61:748–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keyse SM, Tyrrell RM. Heme oxygenase is the major 32-kDa stress protein induced in human skin fibroblasts by UVA radiation, hydrogen peroxide, and sodium arsenite. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:99–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maines MD. Heme oxygenase: Function, multiplicity, regulatory mechanisms, and clinical applications. FASEB J. 1988;2:2557–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsui TY, Lau CK, Ma J, Glockzin G, Obed A, Schlitt HJ, et al. Adeno-associated virus-mediated heme oxygenase-1 gene transfer suppresses the progression of micronodular cirrhosis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2016–23. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i13.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geuken E, Buis CI, Visser DS, Blokzijl H, Moshage H, Nemes B, et al. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 in human livers before transplantation correlates with graft injury and function after transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1875–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schick MA, Wunder C, Wollborn J, Roewer N, Waschke J, Germer CT, et al. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition as a therapeutic approach to treat capillary leakage in systemic inflammation. J Physiol. 2012;590:2693–708. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.232116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flemming S, Schlegel N, Wunder C, Meir M, Baar W, Wollborn J, et al. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibition dose dependently stabilizes microvascular barrier functions and microcirculation in a rodent model of polymicrobial sepsis. Shock. 2014;41:537–45. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekor M, Odewabi AO, Kale OE, Bamidele TO, Adesanoye OA, Farombi EO. Modulation of paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity by phosphodiesterase isozyme inhibition in rats: A preliminary study. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2013;24:73–9. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2012-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: Molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coimbra R, Porcides RD, Melbostad H, Loomis W, Tobar M, Hoyt DB, et al. Nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibition attenuates liver injury in acute endotoxemia. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2005;6:73–85. doi: 10.1089/sur.2005.6.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schick MA, Isbary JT, Stueber T, Brugger J, Stumpner J, Schlegel N, et al. Effects of crystalloids and colloids on liver and intestine microcirculation and function in cecal ligation and puncture induced septic rodents. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schick MA, Isbary TJ, Schlegel N, Brugger J, Waschke J, Muellenbach R, et al. The impact of crystalloid and colloid infusion on the kidney in rodent sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:541–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1704-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wunder C, Brock RW, Krug A, Roewer N, Eichelbrönner O. A remission spectroscopy system for in vivo monitoring of hemoglobin oxygen saturation in murine hepatic sinusoids, in early systemic inflammation. Comp Hepatol. 2005;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brock RW, Carson MW, Harris KA, Potter RF. Microcirculatory perfusion deficits are not essential for remote parenchymal injury within the liver. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G55–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.1.G55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wunder C, Brock RW, McCarter SD, Bihari A, Harris K, Eichelbrönner O, et al. Inhibition of haem oxygenase activity increases leukocyte accumulation in the liver following limb ischaemia-reperfusion in mice. J Physiol. 2002;540:1013–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.015446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorman RB, Wunder C, Brock RW. Cobalt protoporphyrin protects against hepatic parenchymal injury and microvascular dysfunction during experimental rhabdomyolysis. Shock. 2005;23:275–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neuhaus W, Schick MA, Bruno RR, Schneiker B, Förster CY, Roewer N, et al. The effects of colloid solutions on renal proximal tubular cells in vitro. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:371–4. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182367a54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruno RR, Neuhaus W, Roewer N, Wunder C, Schick MA. Molecular size and origin do not influence the harmful side effects of hydroxyethyl starch on human proximal tubule cells (HK-2) in vitro. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:570–7. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu HY, Collins QF, Moukdar F, Zhuo D, Han J, Hong T, et al. Suppression of hepatic glucose production by human neutrophil alpha-defensins through a signaling pathway distinct from insulin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12056–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801033200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koo SH, Flechner L, Qi L, Zhang X, Screaton RA, Jeffries S, et al. The CREB coactivator TORC2 is a key regulator of fasting glucose metabolism. Nature. 2005;437:1109–11. doi: 10.1038/nature03967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermsdorf T, Richter W, Dettmer D. Effects of dexamethosone and glucagon after long-term exposure on cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase 4 in cultured rat hepatocytes. Cell Signal. 1999;11:685–90. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wouters EF, Bredenbröker D, Teichmann P, Brose M, Rabe KF, Fabbri LM, et al. Effect of the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor roflumilast on glucose metabolism in patients with treatment-naive, newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1720–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vollert S, Kaessner N, Heuser A, Hanauer G, Dieckmann A, Knaack D, et al. The glucose-lowering effects of the PDE4 inhibitors roflumilast and roflumilast-N-oxide in db/db mice. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2779–88. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2632-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher JE, McKenzie TJ, Lillegard JB, Yu Y, Juskewitch JE, Nedredal GI, et al. Role of Kupffer cells and toll-like receptor 4 in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. J Surg Res. 2013;180:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchins NA, Chung CS, Borgerding JN, Ayala CA, Ayala A. Kupffer cells protect liver sinusoidal endothelial cells from Fas-dependent apoptosis in sepsis by down-regulating gp130. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:742–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wunder C, Roewer N, Eichelbrönner O. Main determinants of liver microcirculation during systemic inflammation. Anaesthesist. 2004;53:1073–85. doi: 10.1007/s00101-004-0770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubulus D, Mathes A, Pradarutti S, Raddatz A, Heiser J, Pavlidis D, et al. Hemin arginate-induced heme oxygenase 1 expression improves liver microcirculation and mediates an anti-inflammatory cytokine response after hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2008;29:583–90. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318157e526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]