Abstract

Background:

Depression is common among diabetes, and is associated with poor outcomes. However, the data on this important relationship are limited from India.

Objective:

The aim was to estimate the prevalence of depression in patients with diabetes and to determine the association of depression with age, sex, and other related parameters.

Materials and Methods:

The study was cross-sectional carried out in endocrinology clinic of tertiary care hospital in North India. Cases were patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) above 30 years of age. Depression was assessed using the patient health questionairre-9 (PHQ-9). The relationship with sociodemographic profile, duration of diabetes, hypertension and microvascular complications was also analyzed.

Results:

Seventy-three subjects (57.5% females) with mean age 50.8 ± 9.2 years were evaluated. The prevalence of depression was 41%. Severe depression (PHQ score ≥15) was present in 3 (4%) subjects, moderate depression (PHQ score ≥10) in 7 (10%) subjects, and mild depression was present in 20 (27%) of subjects. Depression was significantly more prevalent in rural subjects (57%) when compared to urban ones (31%, P = 0.049). Depression increased with presence of microvascular complications, fasting plasma glucose, hypertension, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusions:

Our study demonstrates higher prevalence of depression in patients with type 2 diabetes. Apart from being belonging to the rural area, no other factor was significantly associated with depression. Therefore, depression should be assessed in each and every patient, irrespective of other factors.

Keywords: Depression, diabetes, patient health questionnaire-9

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and depression are major public health issues. Worldwide, more than 365 million people are estimated to have T2DM, and almost 300 million people have major depression. Both these disorders are projected to be among the five leading causes of disease burden by 2030.[1] Depression can be viewed as a modifiable independent risk factor for the development of T2DM and for progression of complications from either type 1 or type 2 diabetes.[2] The recognition and addressal of this association can have profound implications for prevention and treatment of these disorders.[1] Eighty percent of people with T2DM reside in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Yet much of the research around depression among people with diabetes has been conducted in high-income countries (HICs).[3] This study adds to the limited data available on the prevalence of depression in diabetes from India. It has special relevance for India (middle-income country), having high prevalence of both these disorders.[3,4]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective case study was carried out in September 2014 at the Government Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh (India). This is a tertiary care hospital serving patients from both urban and rural areas. The patients with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes above age 30 years were recruited on voluntarily basis for this study. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used for evaluation of depression, and relevant clinical details were obtained. No intervention was part of the study and the investigations that were available with the patient were used for analysis purpose. The cases were not receiving any psychiatric treatment which could have an effect on the result.

Patient health questionnaire-9

Depression was assessed by administering the nine-item PHQ-9, a self-report version of Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders that assesses the presence of major depressive disorder using modified Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth edition criteria. The PHQ-9 was filled in English by assistance of one of the authors. There is good agreement reported between the PHQ diagnosis and those of independent psychiatry health professionals (for the diagnosis of any one or more PHQ disorder, κ = 0.65; overall accuracy, 85%; sensitivity, 75%; specificity, 90%).[5,6] It assesses the symptoms experienced by participants during the 2-week period before they take the survey. On the basis of participant response to the frequency of any particular symptom (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than ½ of the days, 3 = nearly every day), a total score ranging from 0 to 27 was obtained, with higher scores indicating patients’ increased self-report of depression severity. The arbitrary division of PHQ-9 scores into ratings of minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), and moderate to severe depression (≥10) suggested by Reddy et al. was used in this study.[7] Those who had moderate to severe depression based on cut-off points in PHQ 9 ≥ 10 were referred to Psychiatry Department for further management.

Clinical details

The variables included in the study were socio-demographic factors, the presence of hypertension, microvascular complications were also assessed. Since most of the patients were recruited as first-timers attending the endocrine clinic of the hospital, Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was not available for all patients. The analysis is, therefore, with recent fasting blood glucose (FBG) value (within the last 7 days), which was available for all patients. Moreover, the value of FBG is more easily understood by the patient, rather than interpretation of HbA1c.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were presented as mean ± standard deviation or percentages. Differences in characteristics between participants were tested with unpaired t-test for normally distributed variables, with the Wilcoxon rank sum test for skewed variables, and with the Chi-square test or fisher exact test for categorical variables. The significance level was set at 5%. All statistical analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 20.0, Chicago, IL, USA). A sample size of 73 was as per convenience. This sample size gave us power of 90% with an alpha error of 10%.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

We report data from 73 subjects. The mean age of the study population was 50.8 ± 9.2 years. 57.5% of the subjects were females. 38.4% were from the rural area. 60% of them had coexistent hypertension. About 45% had at least one microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) complication. The mean duration of diabetes was 6.3 ± 6.3 years. Nearly 50% of the subjects had moderate to severe hyperglycemia as indicated by fasting plasma glucose values >150 mg%.

Prevalence of depression

Depression as defined by PHQ score ≥5 was present in 41% of the individuals. Severe depression (PHQ score ≥15) was present in 3 (4%) subjects, moderate depression (PHQ score ≥10) was present in 7 (10%) subjects, and mild depression was present in 20 (27%) of subjects.

Characteristics of subjects with depression

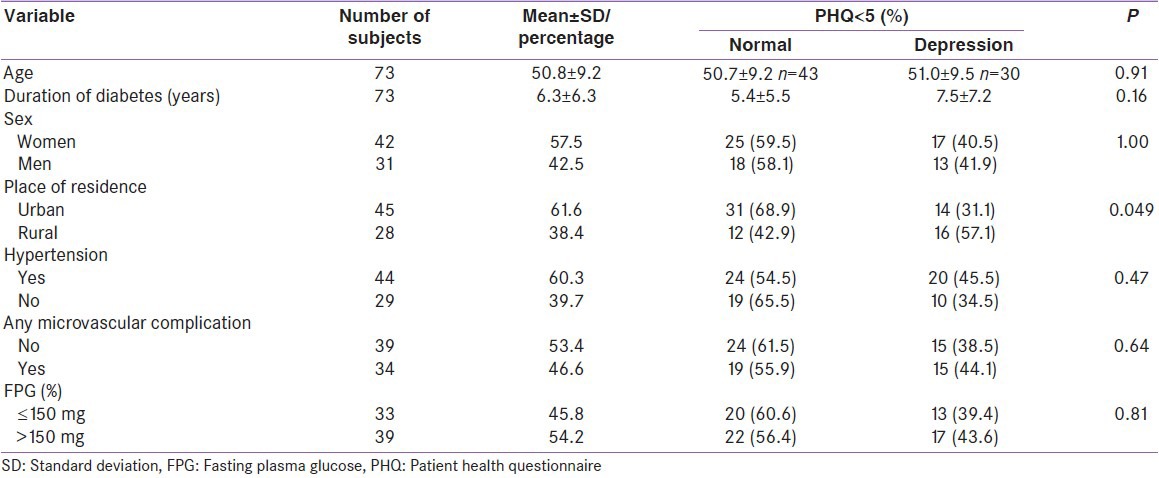

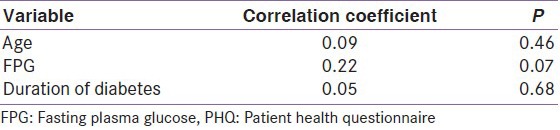

Depression was significantly more prevalent in rural subjects (57%) as compared to urban ones (31%, P = 0.049). The prevalence of depression increased with age and duration of diabetes though the difference was not significant. Men, subjects with hypertension, microvascular complications, and subjects with moderate to severe hyperglycemia had more depression [Table 1]. The differences were, however, nonsignificant. PHQ scores positively correlated with age, duration of diabetes and fasting plasma glucose. The correlations were statistically nonsignificant [Table 2].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population

Table 2.

Correlation of PHQ score with continuous variables

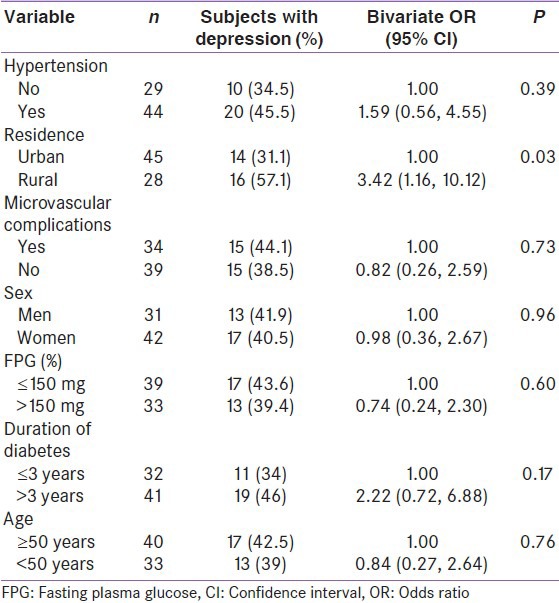

Risk factor analysis

In bivariate risk factor analysis [Table 3], rural subject was nearly three times more likely to have depression (P = 0.03) as compared to urban. Presence of hypertension was associated with 60% more risk of having depression. The risk of depression nearly doubles after 3 years of diagnosis of diabetes. Absence of microvascular complication was associated with 18% less chances of having depression, and fasting plasma glucose ≤150 mg% was associated with 26% lesser risk for depression. There was hardly any difference between men and women for depression.

Table 3.

Risk factor analysis for depression

DISCUSSION

The depression in our study was found in 41% of the patients. High prevalence of depression has been reported from other studies also.[8,9,10,11] The eight studies in India from both urban and rural populations were recently summarized in a systematic review. Of the six urban clinic-based studies, between ¼ and ⅓ of the participants with diabetes were depressed; however, these studies demonstrated great variability (highest was 84%, and lowest was 16.9%).[3] We additionally found three more clinic-based studies from India. In total, four studies used (PHQ-9) questionnaire for the assessment of depression among diabetics in India.[9,10,11,12] The prevalence of depression in T2DM patients in our study (41%) was nearly similar to other studies (35–50%).[9,10,11,12]

There was no sex predilection for depression in our study. Similar findings have been reported by Raval et al. from Chandigarh. Better social fabric and support may be the reasons for same.[10] The interesting finding being higher prevalence of depression in a rural population, when compared to urban ones, and the difference was statistically significant. It may be related to socioeconomic status. The individuals with low earning power face the twin burdens of paying for health care, which is largely out-of-pocket expenditure in India and meeting the needs of their family.[12] The diagnosis of T2DM and its poor understanding in rural areas may be an additional stress causing depression in these people. We found no statistically significant association between depression and duration of diabetes, glycemic control and microvascular complications, the findings, also reported by Siddiqui et al.[11] These findings implicate that the depression should be assessed in all patients with diabetes, irrespective of gender, duration of diabetes, glycemic control or presence/absence of microvascular complications. American Diabetes Association also recommends screening and assessment of depression in patients with diabetes.[13]

A meta-analysis (16 studies), concluded that depression increases all-cause mortality, with the relative risk of dying being 2.5 times higher in depressed compared to nondepressed people. The mortality risk remained high even after additional adjustment for diabetes complications (hazard ratio = 1.76). The information presented, thus far, underscores the extensive adverse effects of untreated depression, including decreased capacity and functioning, increased risk of suicide, and increased medical morbidity and mortality from all causes.[14] However, much of the evidence for depression and type 2 diabetes, came from HICs, and few studies have systematically evaluated depression in diabetes in LMICs, which includes India.[3] Therefore, more understanding on this relationship is essential, and the present study will add to the limited literature available in India on relationship between diabetes and depression.

This study has some limitations. One of the limitations of this study is the small sample size. This study was cross-sectional, so inference about causality between depression and diabetes cannot be made. The study was conducted in tertiary care hospital, so a possible selection bias cannot be excluded, as more depressed/complicated patients might be seeking specialized diabetes care. A large sample from the community could throw more light on this relationship.

To summarize, the present study found a high prevalence of depression among patients with diabetes. Rural individuals are more depressed than the urban ones. Age, sex, duration of diabetes, microvascular complications, hypertension, were not significantly associated with depression. Universal screening for depression should be done in patients with diabetes. Future studies from India, should evaluate the effect of treatment of depression on glycemic control, and also the effect of glycemic control on depression.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tabák AG, Akbaraly TN, Batty GD, Kivimäki M. Depression and type 2 diabetes: A causal association? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:236–45. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams MM, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Treating depression to prevent diabetes and its complications: Understanding depression as a medical risk factor. Clin Diabetes. 2006;24:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendenhall E, Norris SA, Shidhaye R, Prabhakaran D. Depression and type 2 diabetes in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:276–85. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Ma RC. Diabetes in South-East Asia: An update. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittkampf KA, Naeije L, Schene AH, Huyser J, van Weert HC. Diagnostic accuracy of the mood module of the Patient Health Questionnaire: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:388–95. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy P, Philpot B, Ford D, Dunbar JA. Identification of depression in diabetes: The efficacy of PHQ-9 and HADS-D. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:e239–45. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X502128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy T, Lloyd CE, Parvin M, Mohiuddin KG, Rahman M. Prevalence of co-morbid depression in out-patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Bangladesh. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madhu M, Abish A, Anu K, Jophin RI, Kiran AM, Vijayakumar K. Predictors of depression among patients with diabetes mellitus in Southern India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:313–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raval A, Dhanaraj E, Bhansali A, Grover S, Tiwari P. Prevalence and determinants of depression in type 2 diabetes patients in a tertiary care centre. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siddiqui S, Jha S, Waghdhare S, Agarwal NB, Singh K. Prevalence of depression in patients with type 2 diabetes attending an outpatient clinic in India. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:552–6. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph N, Unnikrishnan B, Raghavendra Babu YP, Kotian MS, Nelliyanil M. Proportion of depression and its determinants among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in various tertiary care hospitals in Mangalore city of South India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:681–8. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.113761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann M, Köhler B, Leichsenring F, Kruse J. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in individuals with diabetes: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]