Abstract

Introduction:

This study was designed as a clinical trial to evaluate and compare the regenerative potential of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and blood clot in immature necrotic permanent teeth with or without associated apical periodontitis.

Methods:

Access preparation was done under rubber dam isolation. Copious irrigation was done with 2.5% NaOCl and triple antibiotic paste was placed as an intracanal medicament. After 4 weeks, the cases were divided into four groups with five patients in each group. The study design had three test arms and one control arm. Group I in which mineral trioxide aggregate apexification was carried out and it was kept as control group to evaluate the regenerative potential of blood clot and platelet concentrates, Group II in which blood clot was used as scaffold in the canal, Group III in PRF was used as scaffold, and Group IV in which PRP carried on collagen was used as a scaffold.

Results:

The clinical and radiographic evaluation after 6 and 18 months was done by two independent observers who were blinded from the groups. The scoring was done as: None score was denoted by, Fair by 1, Good by 2, and Excellent by 3. The data were then analyzed statistically by Fisher's exact test using Statistics and Data 11.1(PRP Using harvest Smart PReP2) which showed statistically significant values in Group III as compared to other Groups.

Conclusion:

PRF has huge potential to accelerate the growth characteristics in immature necrotic permanent teeth as compared to PRP and blood clot.

Keywords: Blood clot, immature teeth, platelet-rich fibrin, platelet-rich plasma, scaffold

Introduction

The nonsurgical endodontic management of mature teeth has shown favorable outcome rate of 95% in teeth diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis[1] and 85% in necrotic cases.[2] However, necrotic immature permanent teeth caused either by caries or trauma, offer prognosis due to thin dentinal walls that are prone to fracture.[3,4] Moreover, open apices are difficult to seal either by thermo plasticized or lateral condensation methods.[5] Conventionally such teeth are managed with calcium hydroxide[6,7] or mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) apexification.[8,9] It is reported that 30% of these teeth fracture during or after such treatment.[10] Thus, there was a paradigm shift in the treatment protocol to Regeneration, a biological procedure that offers a huge potential for hard tissue formation in such teeth.[11,12]

The microenvironment in periradicular region for regeneration is dependent upon the spatial orientation of stem cells and signaling molecule on the suitable scaffold.[13,14] Earlier studies on regenerative endodontics utilized blood clot as scaffold with the resultant increase in concentration of growth micromolecules. However, recently platelet concentrates have shown their usefulness in regeneration as they comprise increased concentration of growth factors and increase the cell proliferation over time when compared to the blood clot.[15] There are several in vitro studies supporting the direct dose-response influence of many growth factors like platelet-derived growth factors on cell migration, proliferation, and matrix synthesis.[16,17,18] Hence, the acceleration of the regenerative process can be expected if platelet concentrates are used instead of the blood clot. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP)[19] and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF)[20] represent two concentrated sources of platelets used in the field of maxillofacial and orthopedic surgeries. A natural human blood clot contains 95% red blood cells (RBCs), 5% platelets, <1% white blood cells (WBCs), and numerous amounts of fibrin strands. A PRP clot, on the other hand, contains 4% RBCs, 95% platelets, and 1% WBCs.[21] Platelet count in PRP can exceed 2 million/μL, thus platelet concentration increases by 160% to 740%[22] whereas PRF produces a 210-fold higher concentration of platelets and fibrin when compared to the initial input whole blood volume.[23] PRF, unlike PRP, is associated with slow and continuous increase in cytokine levels.[24] PRP-mediated regeneration of vital tissues in teeth with necrotic pulp and periapical radiolucency has been reported.[25] The purpose of this research work was to evaluate and compare the regenerative potential of the blood clot, PRP, and PRF in immature necrotic permanent teeth.

Materials and Methods

This pilot study was designed as a clinical trial comparing the regenerative potential of the blood clot, PRP, and PRF in young healthy subjects below 20 years of age. Totally, 20 study subjects with necrotic immature permanent teeth with or without associated apical periodontitis were enrolled in the trial. The research protocol was approved by Institutional Reviews Board at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. The study was conducted in Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics at Sir Sunderlal Hospital, BHU between September 2010 and August 2011. Medically compromised patients were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects participating in the study.

Patient's medical, dental history, demographic, and socioeconomic data were collected. Intra oral examination was performed by a single examiner. Pulpal and periradicular status was assessed through percussion, palpation, thermal and electric pulp tests (Diagnostic unit; Sybron, Orange, CA). Periapical radiographic examination was performed using Rinn XCP devices (Rinn Corp, Elgin, IL) and photostimulable phosphor imaging plates. Images were processed and archived by scanner and software interface (OpTime, Soredex, Finland).

Under Rubber dam isolation, access preparation was done in necrotic immature permanent teeth of all the 20 subjects. Canals were copiously irrigated with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite, and minimal instrumentation was done to prevent weakening of the lateral dentinal walls. Triple antibiotic paste was placed as an inter appointment medicament in the dried canals, and the coronal access was sealed with intermediate restorative material for 4 weeks. After 4 weeks, block randomization was done, and cases were divided into four groups with five patients in each group. The study was designed with three test arms and one control arm. The groups were as follows: Group I: MTA apexification (control group), Group II: Blood clot was used as a scaffold, Group III: PRP + collagen was used as a scaffold, Group IV: Platelet-rich Fibrin matrix (PRF or PRFM) was used as scaffold.

Under rubber dam isolation, triple antibiotic paste was removed from the canal using irrigation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite. Canals were dried and following the procedure was carried out.

In Group I, MTA was placed in the canal using messing gun to form the 3–4 mm of apical plug. A moist cotton pellet was placed in the canal, and tooth was temporarily restored for 24 h. It was obturated using gutta-percha and AH Plus sealer. Tooth was permanently restored with adhesive restoration in the same visit.

In Group II, under local anesthesia, a sterile 23 gauge needle was passed 2 mm beyond the confines of working length and pushed with a sharp stroke intentionally to produce bleeding in the canal. When frank bleeding was evident from the canal, a tight cotton pellet was inserted in the coronal portion of canal and pulp chamber for 7–10 min to induce the clot formation in the apical two-third of the root canal.

In Group III, PRF clot was used as a scaffold. It was pushed toward the apical region using endodontic pluggers.

In Group IV, PRP + collagen was introduced as scaffold and pushed toward the apical area using endodontic pluggers.

In all the three experimental groups, resin-modified glass ionomer cement was placed extending 3–4 mm in the canal. Access cavity was sealed with composite (Clearfil Majesty, Kuraray Medical Inc., Tokyo, Japan) during the same visit. Patients were kept on the follow-up period of 6 and 18 months.

Results

All the 20 cases were evaluated clinically and radiographically at 6 and 18 months after treatment. Clinical evaluation considered relief from pain, absence of swelling, drainage and resolution of sinus. Radiographic evaluation included periapical healing, apical closure, root lengthening, and dentinal wall thickening. [Figures 1-4] with respect to Groups I–IV] The clinical and radiographic evaluation was done by two independent observers who were blinded from the groups. Along with it, radiographic measurements were done using radiovisiography software. The scoring was done as follows: None score was denoted by-, Fair by 1, Good by 2, and Excellent by 3, respectively.

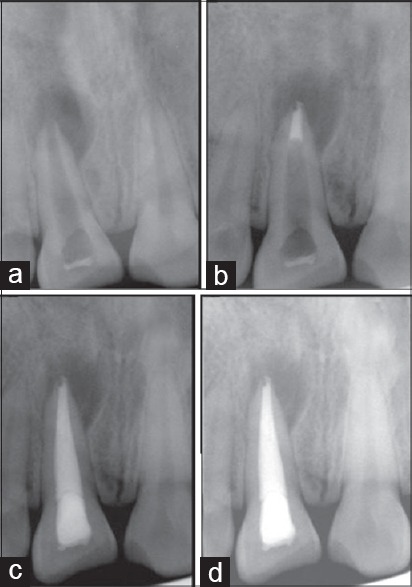

Figure 1.

Group I (a) Preoperative intra oral peri-apical (IOPA) radiograph (b) IOPA radiograph showing MTA plug (c) IOPA radiograph after 6 months (d) IOPA radiograph after 18 months

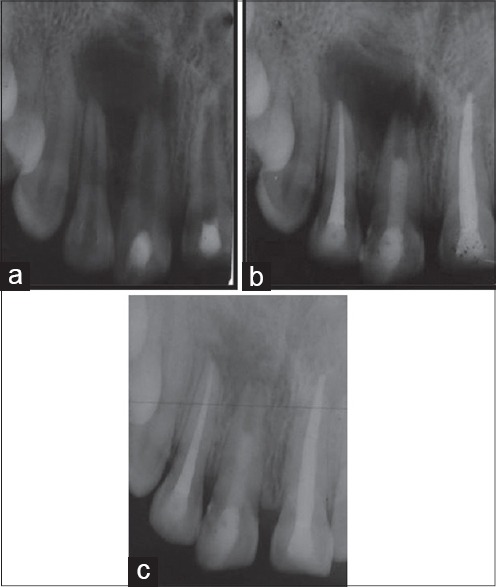

Figure 4.

Group IV (a) Preoperative intra oral peri-apical (IOPA) radiograph (b) IOPA radiograph after 6 months (c) IOPA radiograph after 18 months

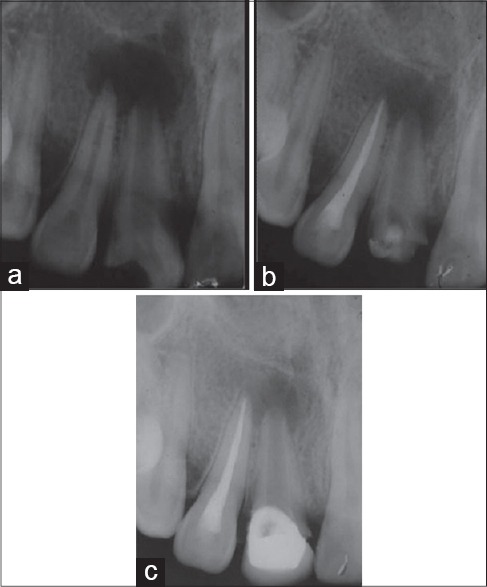

Figure 2.

Group II (a) Preoperative intra oral peri-apical (IOPA) radiograph (b) IOPA radiograph after 6 months (c) IOPA radiograph after 18 months

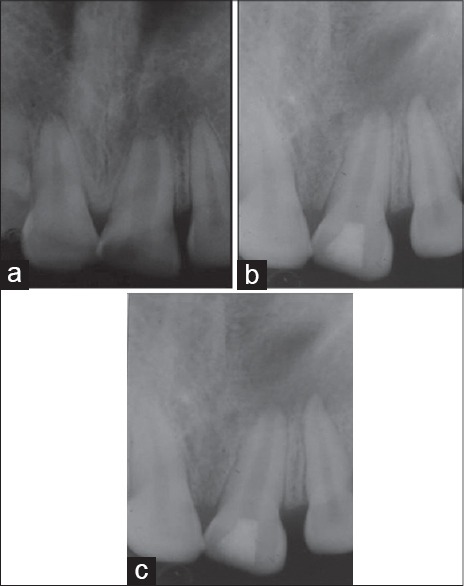

Figure 3.

Group III (a) Preoperative intra oral peri-apical (IOPA) radiograph (b) IOPA radiograph after 6 months (c) IOPA radiograph after 18 months

Clinically, all the groups showed excellent results. Patients were asymptomatic with no tenderness on either percussion or palpation. The swelling and sinus had resolved completely.

The data were then analyzed statistically by Fisher's exact test using STATA11 (PC-02, Process Ltd., Nice, France). 1 software, and P = 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There was no apical closure, root lengthening, and dentinal wall thickening in Group 1 as compared to other groups which was kept as a control group.

Periapical healing

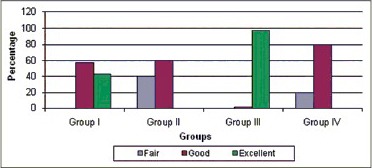

Of five cases in each group, 98% of cases in Group III (PRF group) showed excellent periapical healing with P = 0.003 [Chart 1]. 60% in Group II and 80% in Group IV showed good results with no statistical significant difference between two groups but revascularization supplemented with PRP gave better results than blood clot group.

Chart 1.

Comparative evaluation of periapical healing

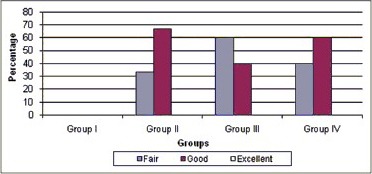

Apical closure

There was no statistical significant difference among Groups II-IV in terms of apical closure with P = 0.417 [Chart 2] 66.67% of cases in Group II, 40% in Group III, and 60% in Group IV showed good apical closure.

Chart 2.

Comparative evaluation of apical closure

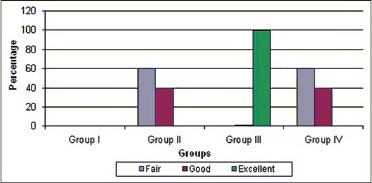

Root lengthening

Ninety-nine percent of the cases in Group III showed excellent results in terms of root lengthening with statistically significant difference over other groups with P = 0.002 [Chart 3]. 40% of the cases in both Groups II and IV showed good results in terms of root lengthening with no difference.

Chart 3.

Comparative evaluation of root lengthening

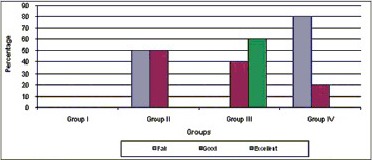

Dentinal wall thickening

Excellent results were seen in 60% of the cases in Group III in terms of dentinal wall thickening with P = 0.047 [Chart 4] good results were obtained in 50% of cases in Group II and 20% of cases in Group IV with no statistical significant difference with Group II showing better results as compared to Group IV.

Chart 4.

Comparative evaluation of dentinal wall thickening

Discussion

The ultimate goal of Regenerative Endodontics is to set the stage for maturogenesis in nonvital immature tooth. It has been reported that the remnants of hertwig's epithelial root sheath or cell rests of Malassez are sufficiently resistant to peri-apical infections.[26] Thus, the signaling networks from these remnant epithelial root sheath cells may stimulate various stem cells like stem cells from apical papillae,[27] periodontal ligament, bone marrow and multipotent pulp stem cells to form odontoblasts-like cells in nonvital, immature and noninfected teeth. These newly formed odontoblasts-like cells from dentine which helps in normal root maturation. This biological process is also mediated by stimulation of cementoblasts at peri-apex leading to deposition of calcific material at apex as well as on lateral dentinal walls. Several research groups have demonstrated the role of morphogens like statins,[28] dexamethasone,[29] LIM mineralization proteins[30] on the differentiation of odontoblasts-like phenotypes from dental stem cells. But the current perspective of various regenerative studies is now to delineate the biological clues in the form of autologous growth micro molecules that basically drive increased stem cell proliferation and differentiation resulting in fast and effective growth. The source of concentrated platelets, that is, PRP and PRF is autologous so, there are little or no chances of immunogenic reactions. These concentrates form a three-dimensional network of fibrin which acts as a scaffold with concentrated growth micro molecules. Fibrin scaffolds give good results when compared to synthetic polymer and collagen gels in terms of cost, inflammation, immune response, and toxicity levels.[15] Such clinical application of concentrated growth factors is an interesting trend in the other fields of dentistry like implants, periodontal surgeries,[31] sinus lift procedures[32] and medical fields like ear, nose, throat surgeries, plastic and orthopedic surgeries. Thus, PRF and PRP were used as a scaffold in inducing revascularization in the present study.

Conventionally, PRP is prepared by collection of venous blood in test tubes containing anticoagulants and then it is subjected to a two-step procedure. In the first step, PRP is formed by separation of a platelet concentrate from the platelet poor plasma, white and red cell fraction.[33] In the second step, exogenous thrombin, or other activator like batroxobin is added together with calcium chloride or calcium gluconate, to the platelet concentrate.[34] This converts fibrinogen into fibrin, and the fibrin network is formed. In contrast, PRF is prepared by collection of patient's blood in dry glass tubes without anticoagulant. The collected blood is centrifuged at low speed which activates platelet activation and fibrin polymerization immediately. Three layers are formed: RBC base layer, acellular plasma on topmost layer, and a PRF clot in the middle. The present study documented the beneficial effect of PRF over PRP, Blood Clot in maturogenesis of necrotic immature permanent teeth. The possible explanations are:

The cytokines are small soluble molecules which remain trapped in PRFM even after serum exudation, which necessarily implies an intimate incorporation of these molecules in the fibrin polymer molecular architecture. The concentration of the cytokines is maximum in matrix formed by PRF as compared to PRP and blood clot

The addition of high thrombin levels for conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin in PRP leads to drastic activation and rapid polymerization leading to dense network of monofibers poor in cytokine concentration whereas slow physiological polymerization in PRF allows the formation of flexible three-dimensional fibrin network that supports cytokine enmeshment and cellular migration

Platelet-rich fibrin shows consistent and stronger healing kinetics than PRP on rat calvaria osteoblasts.[35] PRP basically shows the osteopromotive mechanism and is associated with the significant release of cytokines and mitogens, that is, 81% of total transforming growth factor-β1 and similar levels of total platelet-derived growth factor-AB within the 1st day with significantly decreased release at 3, 7, and 14 days. Since the maximum release of morphogens occurs before the actual cell ingrowth, fewer signaling molecules are left for osteoblasts and odontoblasts from the surrounding tissues. Thus, the effect of PRP on bone and dentine regeneration is limited. However, second-generation platelet concentrate, that is, PRF releases its growth factors steadily with the peak level reaching at 14 days corresponding to the growth pattern of periapical tissues

Platelet-rich plasma generates a strong proliferation, but inhibits differentiation of bone mesenchymal cells (BMSC)[36,37,38] Choukroun's PRF, however shows proliferation and differentiation of BMSC with no associated cytotoxicity toward dental pulp stem cells,[39] periadipocytes, dermal prekeratinocytes, osteoblasts, oral epithelial cells, periodontal ligament cells, and gingival fibroblasts[40]

Platelet-rich fibrin is preferable over PRP in clinical setting as PRP has poor mechanical properties because its liquid or gel form results in washing out of released growth factors such as during an operation in arthroscopic joint repair procedures[41]

The PRF clot is an autologous biomaterial and not an improved fibrin glue. Unlike the PRP, strong fibrin matrix of PRF by Choukroun's technique does not dissolve quickly after application instead, it is remodeled slowly in a similar way to a natural blood clot.[42]

Phase contrast microscopy has shown the attachment of osteoblasts, periodontal ligament cells, and gingival fibroblasts to the edge of PRF membrane. The leukoocyte-rich fibrin clot is fragile in nature[43] because of the presence of GP IIb IIIa receptor on polymorphonuclear leukocytes, thus making handling of clot a little bit difficult. Dr. Joseph Choukroun in 2007 made PRF box for the preparation and standardization of leukocyte- and PRF clots and membranes.[44] These PRF membranes when placed through open apices enhanced the growth characteristics in immature necrotic teeth when compared to PRP and blood clot. It resulted in a reduction in size of periapical radiolucency, increase in thickness of the dentinal walls, and root elongation and apical closure in a shorter period.

Conclusion

Platelet-rich fibrin as a scaffold with concentrated micromolecules or storehouse of growth factors shows significant periapical healing, root lengthening, and dentinal wall thickening in necrotic immature permanent teeth over the blood clot and PRP.

Blood clot and PRP show comparative results in terms of apical closure, root lengthening, dentinal wall thickening, and periapical healing.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Basmadjian-Charles CL, Farge P, Bourgeois DM, Lebrun T. Factors influencing the long-term results of endodontic treatment: A review of the literature. Int Dent J. 2002;52:81–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chugal NM, Clive JM, Spångberg LS. Endodontic infection: Some biologic and treatment factors associated with outcome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(02)91703-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cvek M. Prognosis of luxated non-vital maxillary incisors treated with calcium hydroxide and filled with gutta-percha. A retrospective clinical study. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1992;8:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1992.tb00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trabert KC, Caput AA, Abou-Rass M. Tooth fracture – A comparison of endodontic and restorative treatments. J Endod. 1978;4:341–5. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(78)80232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerezoudis NP, Valavanis D, Prountzos F. A method of adapting gutta-percha master cones for obturation of open apex cases using heat. Int Endod J. 1999;32:53–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank AL. Therapy for the divergent pulpless tooth by continued apical formation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1966;72:87–93. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1966.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steiner JC, Dow PR, Cathey GM. Inducing root end closure of nonvital permanent teeth. J Dent Child. 1968;35:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shabahang S, Torabinejad M. Treatment of teeth with open apices using mineral trioxide aggregate. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 2000;12:315–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witherspoon DE, Ham K. One-visit apexification: Technique for inducing root-end barrier formation in apical closures. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001;13:455–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerekes K, Heide S, Jacobsen I. Follow-up examination of endodontic treatment in traumatized juvenile incisors. J Endod. 1980;6:744–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(80)80186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rule DC, Winter GB. Root growth and apical repair subsequent to pulpal necrosis in children. Br Dent J. 1966;120:586–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwaya SI, Ikawa M, Kubota M. Revascularization of an immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis and sinus tract. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:185–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2001.017004185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hargreaves KM, Giesler T, Henry M, Wang Y. Regeneration potential of the young permanent tooth: What does the future hold? J Endod. 2008;34:S51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920–6. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haupt JL, Donnelly BP, Nixon AJ. Effects of platelet-derived growth factor-BB on the metabolic function and morphologic features of equine tendon in explant culture. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:1595–600. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.67.9.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrahamsson SO. Similar effects of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I and II on cellular activities in flexor tendons of young rabbits: Experimental studies in vitro. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:256–62. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marx RE, Carlson ER, Eichstaedt RM, Schimmele SR, Strauss JE, Georgeff KR. Platelet-rich plasma: Growth factor enhancement for bone grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:638–46. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: Technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sunitha Raja V, Munirathnam Naidu E. Platelet-rich fibrin: Evolution of a second-generation platelet concentrate. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:42–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.38931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): What is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10:225–8. doi: 10.1097/00008505-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucarelli E, Beretta R, Dozza B, Tazzari PL, O’Connel SM, Ricci F, et al. A recently developed bifacial platelet-rich fibrin matrix. Eur Cell Mater. 2010;20:13–23. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v020a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsay RC, Vo J, Burke A, Eisig SB, Lu HH, Landesberg R. Differential growth factor retention by platelet-rich plasma composites. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:521–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torabinejad M, Turman M. Revitalization of tooth with necrotic pulp and open apex by using platelet-rich plasma: A case report. J Endod. 2011;37:265–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safi L, Ravanshad S. Continued root formation of a pulpless permanent incisor following root canal treatment: A case report. Int Endod J. 2005;38:489–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Fang D, Yamaza T, Seo BM, Zhang C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PLoS One. 2006;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okamoto Y, Sonoyama W, Ono M, Akiyama K, Fujisawa T, Oshima M, et al. Simvastatin induces the odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells in vitro and in vivo. J Endod. 2009;35:367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang GT, Shagramanova K, Chan SW. Formation of odontoblast-like cells from cultured human dental pulp cells on dentin in vitro. J Endod. 2006;32:1066–73. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang XY, Zhang Q, Chen Z. A possible role of LIM mineralization protein 1 in tertiary dentinogenesis of dental caries treatment. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:584–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Visser LC, Arnoczky SP, Caballero O, Egerbacher M. Platelet-rich fibrin constructs elute higher concentrations of transforming growth factor-β1 and increase tendon cell proliferation over time when compared to blood clots: A comparative in vitro analysis. Vet Surg. 2010;39:811–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2010.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed TA, Dare EV, Hincke M. Fibrin: A versatile scaffold for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:199–215. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soffer E, Ouahayoun J, Anagnostou F. Fibrin sealants and platelet preparation in bone and periodontal healing. Oral surg Oral med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:521–8. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi BH, Zhu SJ, Jung JH, Lee SH, Huh JY. The use of autologous fibrin glue for closing sinus membrane perforations during sinus lifts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:150–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazzucco L, Medici D, Serra M, Panizza R, Rivara G, Orecchia S, et al. The use of autologous platelet gel to treat difficult-to-heal wounds: A pilot study. Transfusion. 2004;44:1013–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazzucco L, Balbo V, Cattana E, Borzini P. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet gel preparation using Plateltex. Vox Sang. 2008;94:202–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2007.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He L, Lin Y, Hu X, Zhang Y, Wu H. A comparative study of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on the effect of proliferation and differentiation of rat osteoblasts in vitro. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:707–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arpornmaeklong P, Kochel M, Depprich R, Kübler NR, Würzler KK. Influence of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow stromal cells. An in vitro study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:60–70. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogel JP, Szalay K, Geiger F, Kramer M, Richter W, Kasten P. Platelet-rich plasma improves expansion of human mesenchymal stem cells and retains differentiation capacity and in vivo bone formation in calcium phosphate ceramics. Platelets. 2006;17:462–9. doi: 10.1080/09537100600758867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucarelli E, Beccheroni A, Donati D, Sangiorgi L, Cenacchi A, Del Vento AM, et al. Platelet-derived growth factors enhance proliferation of human stromal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3095–100. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang FM, Yang SF, Zhao JH, Chang YC. Platelet-rich fibrin increases proliferation and differentiation of human dental pulp cells. J Endod. 2010;36:1628–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai C, Shen S, Zhao J, Chang Y. Platelet-rich fibrin modulates cell proliferation of human periodontally related cells in vitro. J Dent Sci. 2009;4:130–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maniscalco P, Gambera D, Lunati A, Vox G, Fossombroni V, Beretta R, et al. The “Cascade” membrane: A new PRP device for tendon ruptures. Description and case report on rotator cufftendon. Acta Biomed. 2008;79:223–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, de Peppo GM, Doglioli P, Sammartino G. Slow release of growth factors and thrombospondin-1 in Choukroun's platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A gold standard to achieve for all surgical platelet concentrates technologies. Growth Factors. 2009;27:63–9. doi: 10.1080/08977190802636713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perrin J, Morlon L, Vigneron C, Marchand-Arvier M. Influence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes on the plasma clot formation as evaluated by thromboelastometry (ROTEM) Thromb Res. 2008;121:647–52. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dohan Ehrenfest DM. How to optimize the preparation of leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF, Choukroun's technique) clots and membranes: Introducing the PRF Box. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:275–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.05.048. 278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]