Abstract

Obligate intracellular bacteria have an arsenal of proteins that alter host cells to establish and maintain a hospitable environment for replication. Anaplasma phagocytophilum secrets Ankyrin A (AnkA), via a type IV secretion system, which translocates to the nucleus of its host cell, human neutrophils. A. phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils have dramatically altered phenotypes in part explained by AnkA-induced transcriptional alterations. However, it is unlikely that AnkA is the sole effector to account for infection-induced transcriptional changes. We developed a simple method combining bioinformatics and iTRAQ protein profiling to identify potential bacterial-derived nuclear-translocated proteins that could impact transcriptional programming in host cells. This approach identified 50 A. phagocytophilum candidate genes or proteins. The encoding genes were cloned to create GFP fusion protein-expressing clones that were transfected into HEK-293T cells. We confirmed nuclear translocation of six proteins: APH_0062, RplE, Hup, APH_0382, APH_0385, and APH_0455. Of the six, APH_0455 was identified as a type IV secretion substrate and is now under investigation as a potential nucleomodulin. Additionally, application of this approach to other intracellular bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Chlamydia trachomatis and other intracellular bacteria identified multiple candidate genes to be investigated.

Keywords: Anaplasma phagocytophilum, nucleomodulin, nuclear translocation, oxidative burst, iTRAQ

Introduction

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is an obligate intracellular bacterium of human neutrophils. The neutrophil is an unlikely host as it creates an intracellular milieu that is a highly inhospitable environment for bacterial survival. Yet, A. phagocytophilum requires the neutrophil for propagation and survives by altering the cellular antimicrobial properties while paradoxically increasing pro-inflammatory functions (Banerjee et al., 2000; Carlyon et al., 2002; Borjesson et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2005; Carlyon and Fikrig, 2006). The fitness advantage gained with suppression of microbial killing while enhancing recruitment of new host cells for population expansion is the benefit of this paradoxical dichotomy of functional reprogramming. There is increasing evidence to suggest that the bacterium accomplishes this with coordinated reprogramming of neutrophil gene transcription by reorganizing large regions of host cell chromatin (Sinclair et al., 2014).

Importantly, A. phagocytophilum produces a protein, Ankyrin A (AnkA) that is exported from the bacterium and eventually localizes to the nucleus of the infected host cell (Caturegli et al., 2000; Park et al., 2004). Previously, our laboratory investigated the effect of infection on the transcriptional repression of CYBB, encoding gp91phox (Garcia-Garcia et al., 2009a,b). AnkA is capable of directly binding host cell DNA, and in the case of CYBB, transcription is dampened when AnkA binds to its proximal promoter (Park et al., 2004; Garcia-Garcia et al., 2009a,b). Furthermore, increased histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity enhances A. phagocytophilum infection in part because AnkA recruits HDAC1 to the CYBB promoter to close the chromatin and exclude RNA polymerase binding (Garcia-Garcia et al., 2009a; Rennoll-Bankert and Dumler, 2012). Owing to their capacity to enter the nucleus and modulate host cell transcription, microbial factors such as AnkA have been called “nucleomodulins.”

It is currently unclear as to whether HDAC recruitment is the predominant mechanism by which AnkA exerts its chromatin modulating effects, whether there are other host factors (e.g., polycomb repressive or hematopoietic associated factor-1 [HAF1] complexes), or additional bacterial-derived nucleomodulins that further contribute to reprogramming. The A. phagocytophilum genome encodes a type 4 secretion system (T4SS) that allows the bacteria to translocate effector proteins into the host cytosol (Dunning Hotopp et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2007; Rikihisa et al., 2010). AnkA was the first T4SS substrate identified among Rickettsiales, and it plays a critical and potentially dominant role in the course of establishing and sustaining neutrophil infection (IJdo et al., 2007; Garcia-Garcia et al., 2009a,b; Al-Khedery et al., 2012; Rennoll-Bankert and Dumler, 2012). In contrast to other gram-negative T4SSs, the vir genes encoding the secretion system of the Rickettsiales family are organized differently in that they are clustered in three different genomic locations (Ohashi et al., 2002; Rikihisa et al., 2010). Between individual A. phagocytophilum strains, variations of the T4SS appear to contribute to host specificity and strain virulence (Al-Khedery et al., 2012).

We hypothesize that A. phagocytophilum expresses additional nuclear effector proteins secreted by its type IV secretion system (T4SS) and that these also play a role in pathogenicity. It is likely that some will be nucleomodulins which could contribute to transcriptional reprogramming of infected neutrophils. Pilot studies using bioinformatics tools, and iTRAQ protein profiling among infected and uninfected cells were used to identify candidate proteins that potentially localize to the host cell nucleus. The profiling identified 50 A. phagocytophilum proteins, one of which was AnkA, and at least 7 of these were predicted to enter the nucleus based on the presence of both a nuclear localization sequence and a bacterial secretion signal sequence. Ultimately, 3 of the 7 proteins identified in the bioinformatic screen and 3 of 37 identified by iTRAQ profiling of nuclei from infected cells translocated into HEK-293T human embryonic kidney and PLB-985 granulocytic cell nuclei.

Methods

In silico prediction of A. phagocytophilum proteins targeted to the host cell nucleus

Our initial focus was on proteins involved in regulation of host gene expression. Since these events occur chiefly in the nucleus, we developed an unbiased computational approach to identify potential nucleomodulins encoded in intracellular bacterial genomes based on their likelihood for translocation into the host cell nucleus and applied this to the A. phagocytophilum HZ strain genome (Supplemental Figure 1). Annotated protein tables for bacteria, focusing on the A. phagocytophilum HZ strain genome, were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria). The A. phagocytophilum protein table was used as the database for eukaryotic subcellular localization search algorithms. Although we used a database with 1264 annotated A. phagocytophilum proteins, including hypothetical proteins, multiple programs were implemented to obtain high prediction accuracy and processing capacity. Since we needed only to predict nuclear proteins, localization coverage was not taken into account. Since hybrid methods are preferable when little is known about the protein of interest (Donnes and Hoglund, 2004) we used ProtComp Version 6 (Softberry, Inc.), a computational algorithm for the identification of sub-cellular localization of eukaryotic proteins.

We next applied PSORTb v.2.0 to exclude potential membrane proteins that are unlikely to be secreted into the host cell (Gardy et al., 2005). Finally, we used computational algorithms to predict the presence of eukaryotic nuclear localization signals (NLS). NLSs often possess sequences with a high basic amino-acid content (Hicks and Raikhel, 1995) and are generally classified into three categories: classical or monopartite (NLSm), bipartite (NLSb), and a type of N-terminal signal found in yeast protein, Mat alpha2, a poorly studied signal that is not incorporated in most NLS prediction algorithms. To screen broadly for potential NLSs, we selected MultiLoc (Hoglund et al., 2006). MultiLoc also identifies matches in NLSdb, a database of experimentally known NLSs (Nair et al., 2003) and is also useful to predict NLSm and NLSb in addition to the NLSdb attribute, since NLSdb recognizes only 43% of the nuclear proteins. MultiLoc calculates a probability estimate for each subcellular location and the protein is assigned to the compartment with the highest score. The MultiLoc output was recorded and used to calculate a Nuclear Score that better reflects the purpose of the search:

where: (i) 0 ≤ MultiLoc Nuc <1 is the probability estimate of the protein being nuclear as calculated by MultiLoc; (ii) NLSdb is 1 if the protein contains a known NLS, 0 if not; (iii) NLSm is 1 if the protein contains a predicted NLSm, 0 if not; and (iv) NLSb is 1 if the protein contains a predicted NLSb, 0 if not. Weighting was applied since the presence of a predicted NLS suggests, but is not conclusive; therefore the NLSm or NLSb prediction contributes only half to the final nuclear score. The addition of the continuous MultiLoc Nuc score provides a better ranking of the proteins, given that the other indicators contribute discretely to the Nuclear Score. However, no proteins without a known or predicted NLS will produce a Nuclear Score >1 since MultiLoc Nuc <1.

iTRAQ for identification of potential nuclear-translocated protein profiling

A. phagocytophilum-infected and uninfected HL-60 cells, a promyelocytic cell line commonly used for A. phagocytophilum propagation as previously described (Goodman et al., 1996; Park et al., 2004), were fractionated to obtain nuclei and nuclear proteins. iTRAQ (isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation protein profiling technology [Applied Biosystems]), a mass spectrometric technique where 2 protein expression profiles are compared, was used to identify candidate bacterial proteins present in the nucleus of infected cells. One hundred μg in replicate samples from nuclear fractions of infected and uninfected HL-60 cells were acetone-precipitated and checked for protein integrity and sample quality. The samples were reduced and cysteines blocked following the iTRAQ kit protocol (Applied Biosystems). Samples were digested with trypsin overnight at 37°C and then labeled with iTRAQ tags in replicates, pooled and fractionated using a strong cation exchange (SCX) column on an Ultimate HPLC system (LC Packings). Approximately 20 fractions were collected and analyzed on Qstar Pulsar™ (Applied Biosystems-MDS Sciex) interfaced with an Agilent 1100 HPLC system. Peptides were separated on a reverse-phase column, and MS/MS analysis was performed. The MS/MS spectral data were extracted and searched against Uniprot-sprot database (entries for Homo sapiens and A. phagocytophilum) using ProteinPilot™ software (Applied Biosystems). For each protein, two types of scores were reported: unused ProtScore and total ProtScore. The total ProtScore is a measurement of all the peptide evidence for a protein and is analogous to protein scores reported by other protein identification software programs. However, the unused ProtScore is a measurement of all the peptide evidence for a protein that is not better explained by a higher ranking protein and was the method of choice. The protein confidence threshold cutoff for this study was set at an unused score of 2.0 with at least one peptide with 99% confidence. A ratio of infected to uninfected (Aph:HL-60) score was used to identify A. phagocytophilum proteins in nuclear lysates. To do this, we averaged the ratios of uninfected HL-60 nuclear lysate replicates (isobaric isotope labels 115:114) and ratios of nuclear lysate replicates from A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells (116:114 and 117:114) to create the composite Aph:HL-60 mean ratio. Proteins identified with mean ratios (infected/uninfected) >1.2 were selected for further study.

GFP-fusion protein plasmid clones and transfections

Forty one GFP C-terminal fusion proteins were prepared using pMAXFP-Green-C (Lonza, cat# AMA-VDF1011) and the Infusion HD Liquid cloning kit (Clontech). Briefly, target genes were amplified using PlatinumTaq (Life Technologies) and PCR purified using Qiagen PCR purification kits (Qiagen). Primers were designed using Clontech's Online Infusion tools, Primer Design. Amplicons were created to be fused with the pMAXFP-Green-C vector after digestion with XhoI. Primers were approximately 40–45 bp in length and had the sequence GAAGAAAGATCTCGAGCT added to the 5′ end of the forward gene-specific primer (20–25 bp), and GAAGCTTGAGCTCGAGT added 5′ to the reverse primer (Supplemental Table 1). The Infusion-HD kit instructions were followed as per the manufacturer's recommendations. Clones were transformed into E. coli JM109 (Promega) and after antibiotic selection, were sequenced to ensure they were in the correct orientation and in frame. HEK-293T cells were transfected with GFP-fusion vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) and PLB-985 cells were transfected with the Amaxa Nucleofector shuttle and the SF kit reagents (Lonza) as per manufacturer's recommendations. PLB-985 cells are human myelomonoblast leukemia cells that easily differentiate into neutrophil-like cells and are readily transfected as opposed to HL-60 cells, a common host cell model for A. phagocytophilum infection (Pedruzzi et al., 2002; Ellison et al., 2012; Rennoll-Bankert et al., 2014). Cells were stained with DAPI 24 h later and imaged by fluorescence microscopy, gathering both superimposed green fluorescent protein and DAPI images.

Determination of T4SS substrates

A. phagocytophilum proteins that localized to the nucleus of HEK-293T and PLB-985 cells were tested for their ability to be secreted by the T4SS Dot/Icm system of Coxiella burnetii RSA439 avirulent phase II nine-mile strain using adenylate cyclase translocation assays (Larson et al., 2013). Fusion proteins were created by cloning full-length coding regions or C-terminal 100 aa truncations to the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase gene (cyaA). To achieve this, C. burnetii was transiently propagated in ACCM-2 axenic culture medium and transformed with the constructs (performed at the NIAID Rocky Mountain Laboratories [Hamilton, MT] by Paul Beare, Ph.D. and Charles L. Larson). Axenic C. burnetii was transformed by electroporation and cultured in ACCM-2 medium for 24 h followed by chloramphenicol selection (Beare et al., 2009; Voth et al., 2011). The ability of the constructs to be secreted by the Dot/Icm system was determined by measuring changes in intracellular cAMP levels. CyaA fusion proteins that contain a T4SS signal are capable of being secreted and mediate a measurable increase in cAMP. C. burnetii transformants containing the cyaA constructs were used to infect THP-1 cells (a human myelomonocytic cell line) at an MOI of 100:1, and included both A. phagocytophilum AnkA (APH_0740) and Coxiella vacuolar protein A (CvpA), both known T4SS substrates as positive controls. After 3 days, the cells were harvested, lysed and examined for cAMP production by enzyme immunoassay. Results were expressed as fold change in intracellular cAMP concentration compared to empty vector control (CyaA only) that lacked a T4SS signal; values >2 were considered positive for type 4 secretion; values between 1 and 2 were considered marginal.

Assay for detection of reactive oxygen species

Superoxide production was detected as described previously (Rennoll-Bankert et al., 2014). Briefly, HL-60 cells were incubated with 0.25 mM 2′,7′-dichlorofluoresein diacetate (DCFH-DA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. 105 cells were stimulated in triplicate with 1 μg/mL phorbol 12-myristate 12-acetate (PMA) and fluorescence was measured every 2 min. The relative fluorescence units at 180 min were averaged and compared to unstimulated controls using a two-sided Student's t-test, α 0.05.

Results

In silico prediction of A. phagocytophilum proteins targeted to the host cell nucleus

Of 1264 proteins and hypothetical proteins examined by the bioinformatics algorithm, 123 were identified by ProtComp as nuclear-localized; 3 of these were classified in PSORTb as potentially nuclear membrane-associated; after analysis of NLSdb and screening for NLSm and NLSb, 7 candidate proteins had a total Nuclear score >1 (Table 1). One candidate with a high ProtComp score for nuclear localization but that lacked a predicted NLS (APH_0805) was selected as a control. The known nuclear-translocated AnkA was not identified in this screen.

Table 1.

Bioinformatic prediction of A. phagocytophilum nuclear-translocated proteins, by likelihood based on Final Score rank.

| Locus name | Acc. No. | Protein | Gene | Ranking | ProtComp | MultiLoc | NLS | NLS1 | NLS2 | Final score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APH_0820a | YP_505397.1 | Hypothetical protein | 10 | 2.1 | 0.94 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2.44 | |

| APH_0847 | YP_505424.1 | Hypothetical protein | 22 | 2.1 | 0.97 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1.97 | |

| APH_0382 | YP_504988.1 | HGE-14 protein | 56 | 1.7 | 0.97 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.47 | |

| APH_0385 | YP_504990.1 | HGE-14 protein | 75 | 2.1 | 0.94 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.44 | |

| APH_0455 | YP_505057.1 | HGE-14 protein | 76 | 2.2 | 0.94 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.44 | |

| APH_0485 | YP_505084.1 | Hypothetical protein | 77 | 2.2 | 0.94 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.44 | |

| APH_0576 | YP_505167.1 | RNA polymerase sigma factor RpoD | rpoD | 114 | 2.1 | 0.89 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.39 |

| APH_0805b | YP_505382.1 | Hypothetical protein | 1891 | 2.1 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.96 |

Not cloned.

Selected as negative control.

iTRAQ identification of A. phagocytophilum nuclear-translocated proteins

We detected 43 A. phagocytophilum proteins with an Aph:HL-60 ratio >1.2 in the nucleus of infected cells (Table 2), including the top hit, AnkA that is established to translocate into the nucleus. This approach allowed the identification of A. phagocytophilum proteins most likely to have been translocated into the nucleus and provided a more complete list of candidates to investigate out of the 1264 A. phagocytophilum ORFs available for study. Of these 43 candidates, only AnkA was excluded from subsequent cloning and expression for in vitro nuclear localization studies.

Table 2.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum proteins identified in the nuclear lysates of infected HL-60 cells by iTRAQ with ratios compared with uninfected cells of >1.2 and ranked by Unused ProtScore to identify high likelihood candidates for nuclear translocation.

| Locus name | Accession | Protein | Gene | Ratios of labeled peptidesa | Mean HL-60 | Mean Aph | Ratio Aph:HL-60 | Unused ProtScore | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 115:114 | 116:114 | 117:114 | ||||||||

| APH_0740 | gi|88607707 | Ankyrin A | ankA | 1.06 | 1.42 | 1.43 | 1.03 | 1.43 | 1.38 | 40.10 |

| APH_1023 | gi|88607105 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta; RNAP subunit beta | rpoC | 1.04 | 1.50 | 1.39 | 1.02 | 1.45 | 1.42 | 32.10 |

| APH_0240 | gi|88606723 | 60 kDa chaperonin GroEL | groEL | 1.00 | 1.88 | 1.93 | 1.00 | 1.90 | 1.90 | 30.60 |

| APH_10242 | gi|88606872 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta; RNAP subunit beta | rpoB | 1.02 | 1.33 | 1.27 | 1.01 | 1.30 | 1.28 | 23.40 |

| APH_0906 | gi|88606911 | Hypothetical protein APH_0906 | 1.05 | 1.25 | 1.22 | 1.02 | 1.24 | 1.21 | 20.70 | |

| APH_02782 | gi|88607578 | Translation elongation factor Tu; EF-Tu | tuf1 | 1.18 | 1.93 | 1.83 | 1.09 | 1.88 | 1.73 | 20.20 |

| APH_1099 | gi|88607685 | DNA-binding response regulator CtrA | ctrA | 1.05 | 2.65 | 2.71 | 1.03 | 2.68 | 2.62 | 19.90 |

| APH_0303 | gi|88606699 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha; RNAP subunit alpha | rpoA | 1.16 | 1.91 | 1.84 | 1.08 | 1.88 | 1.74 | 15.90 |

| APH_0784 | gi|88606926 | DNA-binding protein HU | hup | 1.00 | 2.38 | 2.03 | 1.00 | 2.21 | 2.21 | 15.40 |

| APH_0968 | gi|88606840 | ATP-dependent protease La | lon | 1.01 | 1.62 | 1.44 | 1.01 | 1.53 | 1.52 | 15.10 |

| APH_1100 | gi|88606714 | DNA-binding protein | 0.99 | 2.82 | 2.44 | 0.99 | 2.63 | 2.64 | 13.80 | |

| APH_0469 | gi|88607025 | Putative malonyl-CoA decarboxylase | 1.04 | 1.27 | 1.28 | 1.02 | 1.27 | 1.24 | 12.60 | |

| APH_0445 | gi|88607683 | Transcription elongation factor NusA | nusA | 1.00 | 1.53 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.52 | 1.52 | 12.20 |

| APH_0339 | gi|88607311 | Putative thermostable metallocarboxypeptidase | 1.11 | 1.59 | 1.58 | 1.05 | 1.58 | 1.50 | 9.60 | |

| APH_1239 | gi|88607921 | P44–15b outer membrane protein; major surface protein-2C | p44–15b | 1.05 | 3.60 | 3.63 | 1.03 | 3.62 | 3.53 | 9.10 |

| APH_0062 | gi|88606901 | Hypothetical protein APH_0062 | 1.06 | 1.91 | 1.77 | 1.03 | 1.84 | 1.79 | 8.70 | |

| APH_1097 | gi|88607712 | DNA polymerase III, beta subunit | dnaN | 1.14 | 1.33 | 1.30 | 1.07 | 1.32 | 1.23 | 6.60 |

| APH_0135 | gi|88606701 | Cold shock protein, CSD family | 0.97 | 1.79 | 1.78 | 0.99 | 1.79 | 1.81 | 6.30 | |

| APH_0397 | gi|88606909 | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | rpsB | 1.07 | 1.53 | 1.45 | 1.04 | 1.49 | 1.44 | 6.20 |

| APH_1263 | gi|88607227 | Translation initiation factor IF-3 | infC | 0.94 | 2.12 | 1.97 | 0.97 | 2.05 | 2.11 | 5.00 |

| APH_0398 | gi|88607503 | Elongation factor Ts; EF-Ts | tsf | 1.03 | 1.24 | 1.28 | 1.01 | 1.26 | 1.24 | 4.40 |

| APH_1151 | gi|88607101 | Hypothetical protein APH_1151 | 1.20 | 2.16 | 2.11 | 1.10 | 2.13 | 1.94 | 4.10 | |

| APH_0288 | gi|88607038 | 50S ribosomal protein L29 | rpmC | 1.03 | 1.77 | 1.66 | 1.01 | 1.72 | 1.69 | 4.10 |

| APH_1029 | gi|88607731 | Transcription termination/antitermination factor NusG | nusG | 0.94 | 1.65 | 1.72 | 0.97 | 1.69 | 1.74 | 4.00 |

| APH_1027 | gi|88607420 | 50S ribosomal protein L1 | rplA | 1.15 | 1.37 | 1.26 | 1.08 | 1.31 | 1.22 | 3.30 |

| APH_0515 | gi|88606905 | Expression regulator ApxR | apxR | 0.99 | 2.02 | 1.94 | 0.99 | 1.98 | 2.00 | 3.20 |

| APH_0097 | gi|88606982 | Protein-export protein SecB | secB | 1.11 | 1.81 | 1.67 | 1.06 | 1.74 | 1.64 | 3.00 |

| APH_0292 | gi|88606711 | 50S ribosomal protein L5 | rplE | 1.26 | 1.52 | 1.57 | 1.13 | 1.54 | 1.36 | 2.40 |

| APH_0106 | gi|88607568 | Riboflavin synthase, alpha subunit | ribE | 0.98 | 2.04 | 2.00 | 0.99 | 2.02 | 2.04 | 2.30 |

| APH_0280 | gi|88607449 | 50S ribosomal protein L3 | rplC | 1.07 | 1.60 | 1.64 | 1.04 | 1.62 | 1.56 | 2.30 |

| APH_0629 | gi|88607793 | Malate dehydrogenase | mdh | 0.98 | 1.25 | 1.21 | 0.99 | 1.23 | 1.24 | 2.30 |

| APH_01602 | gi|88606875 | Putative thymidylate synthase, flavin-dependent, truncation | 1.14 | 1.50 | 1.37 | 1.07 | 1.44 | 1.34 | 2.20 | |

| APH_0154 | gi|88607134 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase SHMT | glyA | 1.06 | 1.29 | 1.26 | 1.03 | 1.27 | 1.24 | 2.10 |

| APH_0971 | gi|88607838 | Trigger factor; TF | tig | 1.04 | 1.37 | 1.28 | 1.02 | 1.32 | 1.30 | 2.00 |

| APH_0659 | gi|88607183 | Antioxidant, AhpC/Tsa family | 0.99 | 1.26 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.24 | 1.25 | 2.00 | |

| APH_1349 | gi|88606948 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, type I | gap | 0.86 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 0.93 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 2.00 |

| APH_1198 | gi|88606994 | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, E2 component, dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase | sucB | 0.98 | 1.24 | 1.16 | 0.99 | 1.20 | 1.21 | 2.00 |

| APH_1025 | gi|88607605 | 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 | rplL | 1.01 | 1.85 | 1.79 | 1.01 | 1.82 | 1.81 | 1.90 |

| APH_02892 | gi|88607574 | 30S ribosomal protein S17 | rpsQ | 0.90 | 1.57 | 1.46 | 0.95 | 1.52 | 1.60 | 1.70 |

| APH_10342 | gi|88607212 | 30S ribosomal protein S7 | rpsG | 1.16 | 1.42 | 1.41 | 1.08 | 1.41 | 1.31 | 1.50 |

| APH_01962 | gi|88607673 | Response Regulator NtrX, putative nitrogen assimilation regulatory protein | ntrx | 0.93 | 1.70 | 1.50 | 0.97 | 1.60 | 1.66 | 1.40 |

| APH_13332 | gi|88607617 | Transcription elongation factor GreA | greA | 0.95 | 1.29 | 1.27 | 0.98 | 1.28 | 1.31 | 1.30 |

| APH_1098 | gi|88607131 | 3′–5′ exonuclease family protein | 1.12 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 1.06 | 1.30 | 1.22 | 1.30 | |

Isobaric ion labels of nuclear lysates from: 114 and 115, uninfected HL-60 cells; 116 and 117, A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells.

b Not cloned.

In vitro nuclear localization

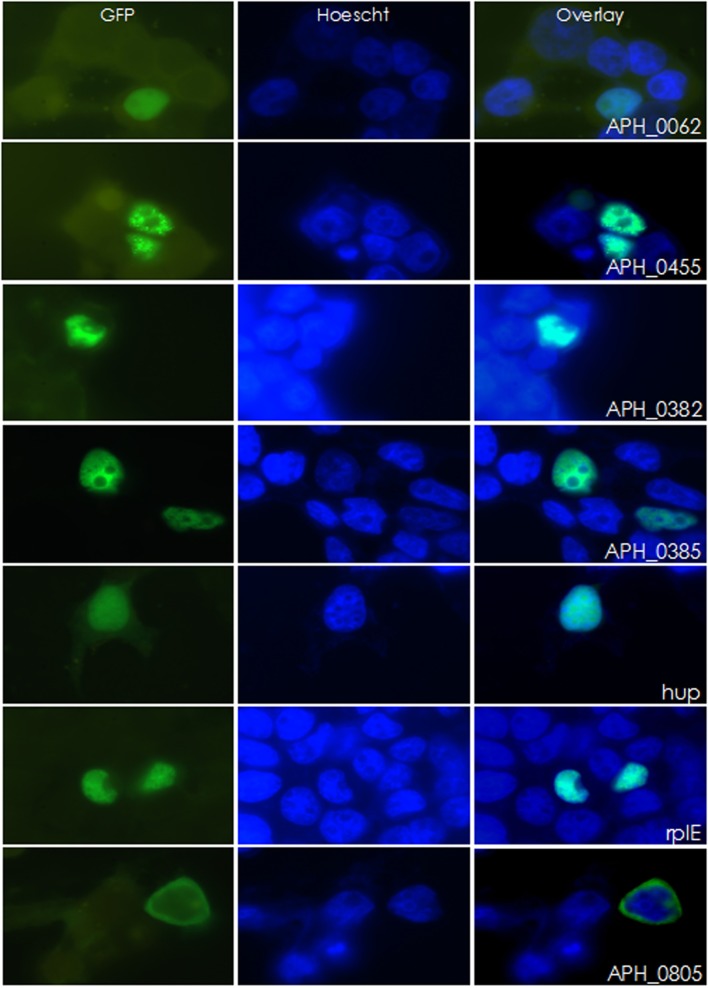

As an inclusive screen, and because contamination of nuclear preparations could not be entirely excluded in iTRAQ studies, nuclear localization of proteins identified by bioinformatic methods or by iTRAQ mass spectrometry were confirmed by cloning the corresponding genes into a mammalian expression vector for expression as GFP fusion proteins. APH_0805 that was predicted to have nuclear localization yet lacked a predicted NLS and had a below-threshold Nuclear score was used as a non-translocating control. HEK-293T cells and PLB-985, a promyelocytic cell line, were transfected and examined for nuclear localization of the GFP-fusion proteins with Hoescht 33342 nuclear counterstaining. Six of the 42 proteins tested (36 from iTRAQ profiling, 7 from the bioinformatic screen), translocated to the nucleus: APH_0062 (hypothetical protein), RplE (50S ribosomal protein L5 [APH_0292]), Hup (DNA-binding protein HU [APH_0783]), and APH_0455, APH_0382, and APH_0385 (all HGE-14) (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 2). APH_0278 (tuf-1; elongation factor Tu) was not cloned, but instead the identical APH_1032 (tuf-2; elongation factor Tu) was used but did not enter the nucleus. Nine proteins were either unable to be cloned or cloning was not attempted, including: APH_0160 (putative thymidylate synthase, flavin-dependent, truncation, partial); APH_0196 (nitrogen assimilation regulatory protein); APH_0289 (ribosomal protein S17 [rpsQ]); APH_0820 (hypothetical protein); APH_0906 (hypothetical protein); APH_1023 (DNA-directed RNA polymerase, beta subunit [rpoC]); APH_1024 (DNA-directed RNA polymerase, beta subunit [rpoB]); APH_1034 (ribosomal protein S7 [rpsG]) and APH_1333 (transcription elongation factor GreA).

Figure 1.

Six A. phagocytophilum candidate genes were found to localize to the nucleus of HEK-293T cells. Candidate genes were fused to GFP and transfected into HEK-293T cells. Twenty four hours post-transfection, cells were stained with DAPI and imaged. Of the 42 GFP-fusion proteins created, six localized to the nucleus. APH_0805 is shown here as an example of a protein that did not localize to the nucleus.

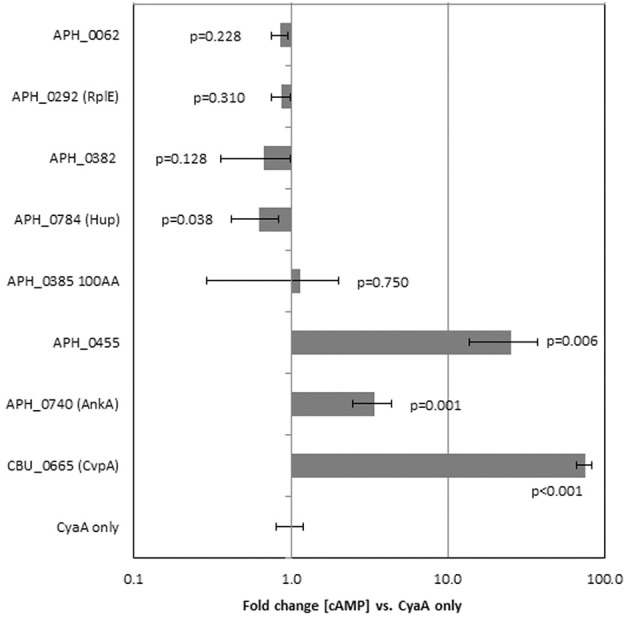

Determination of type 4 secretion substrates

Proteins identified to localize to the nucleus were further investigated to determine if they could be secreted by the T4SS of Coxiella burnetii, which is similar to that of A. phagocytophilum. T4SS substrate status was determined by the ability of the CyaA-fusion to exit C. burnetii and produce a measurable increase in cAMP concentrations with infection of THP-1 cells. Of the 6 genes tested only APH_0455 was identified to be a type 4 secretion substrate (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

APH_0455 is secreted by the Dot/Icm T4SS of C. burnetii. Candidate genes were fused to B. pertussis adenylate cyclase (cyaA), transfected into C. burnetii and selected by chloramphenicol resistance. Transformed C. burnetii clones were then used to infect THP-1 cells. Three days post-transfection, THP-1 cells were assayed for cAMP production. Only those constructs that contain a T4SS signal sequence have measurable changes in cAMP production. The results represent the average of two separate experiments each with replicate tests. The p-values were calculated based on comparisons with fold change of C. burnetii transformed by empty plasmid (CyaA only) using two-sided Student's t-tests, α = 0.05. CBU_0655 is CvpA, a known T4SS substrate of C. burnetii.

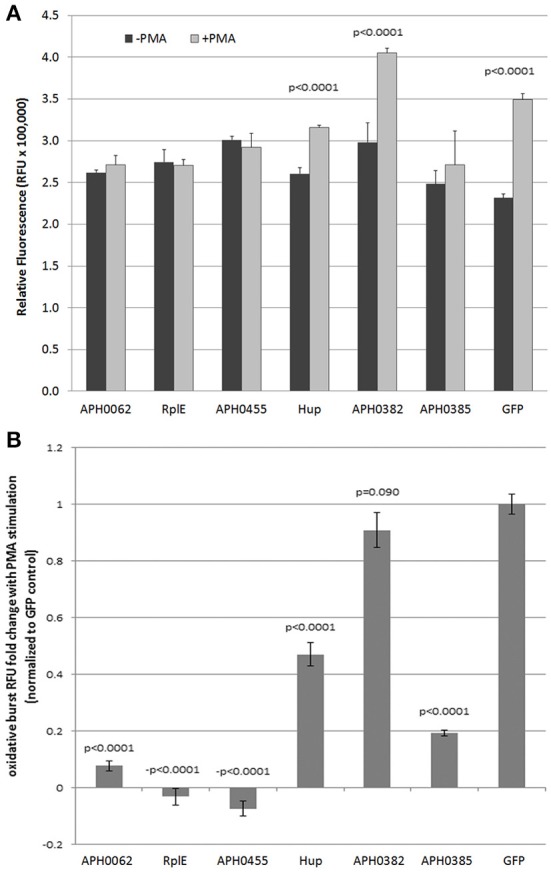

Determination of oxidative burst after transfection and nuclear translocation

GFP-fusion constructs were transfected into HL-60 cells to determine their ability to alter the oxidative burst response. Unfortunately, the methods (electroporation, lipofectamine, viral transduction) used to transfect the HL-60 cells (differentiated or undifferentiated), abrogated oxidative burst as compared with non-transfected cells. Thus, we compared results to PMA-stimulated oxidative burst in HL-60 cells transfected with the empty GFP plasmid as control. When RFU values of each unstimulated transfected control cell culture were compared to PMA-stimulated, significant oxidative burst, as seen with the GFP plasmid control, was observed only with Hup and APH_0382 (Figure 3A). When normalized to GFP plasmid transfection alone, APH_0062, RplE, APH_0455, Hup, and APH_0385 significantly repressed respiratory burst (Figure 3B). However, responses varied in intensity over several repeated experiments, likely in part due to the variable transfection efficiency obtained with HL-60 cells. These data suggest that one or more of these effectors could contribute to dampened production of reactive oxygen species.

Figure 3.

Expression of putative nuclear effectors APH_0062, RplE and APH_0455 dampen PMA-stimulated reactive oxygen species production by HL-60 cells. HL-60 cells were transfected with 2 μg plasmid and assayed for respiratory burst 48 h later. (A) The average of three replicates is displayed ±SEM at 180 min. (B) The fold change was calculated by dividing the ratio of PMA stimulation of each transfectant to the GFP control. P-values were calculated using Students t-tests.

Discussion

While considerable focus has been placed on AnkA as the primary nucleomodulin of A. phagocytophilum, it does not seem plausible that a single protein can account for the widespread transcriptional and phenotypic changes induced with infection. Using current bioinformatics tools and mass spectrometry, a number of other proteins encoded in the A. phagocytophilum genome were identified that could potentially localize to the host cell nucleus. To validate the candidate genes, GFP-fusion proteins were created and screened for nuclear localization within HEK-293T cells. This approach narrowed the list of target genes for further investigation to six.

No candidate proteins were identified in both the bioinformatic screen and in the iTRAQ mass spectrometry analysis. If one assumes that the mass spectrometry data is accurate, the bioinformatic approach was ineffective at identifying features to predict nuclear localization for 3 of the six proteins shown capable of entering the nucleus; as a result, APH_0062 (cytoplasmic), hup, and rplE (both mitochondrial) were excluded from the bioinformatic identification because they were not assigned a nuclear localization. In contrast, no bioinformatic-predicted candidate appeared in the iTRAQ mass spectrometry analyses, suggesting limitations in sensitivity and/or contamination of nuclear preparations by non-nuclear localized proteins. Thus, the combination of both approaches increased the ability to identify and exclude candidates for further analysis. It is important to note that the screen will only identify those genes capable of entering the nucleus on their own accord via an identified or unidentified nuclear localization signal. Some proteins identified as present in the nucleus in the iTRAQ screen could indeed localize to the nucleus but might not be confirmed by transfection screens. A bacterial-derived protein shuttled into the nucleus as a component of a protein complex, or one that possesses an uncharacterized NLS, as is the case with AnkA, would not be identified. Furthermore, HEK-293T cells are not a model cell line for A. phagocytophilum infection and transfection of these proteins does not mimic infection, a much more complex process; therefore, confirmation of nuclear translocation in PLB-985 was performed.

Additionally, A. phagocytophilum is largely refractory to gene delivery by genetic transformation. Previous reports demonstrate A. phagocytophilum transformation using the Himar1 transposase system that introduces small GFP proteins or disrupts bacterial genes and consequently protein expression (Felsheim et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2012). This process does not result in gene entry, but results in a library of mutant bacteria that can facilitate complex functional studies and insight into the importance of mutated genes for establishing or maintaining infection. However, directed mutation by homologous recombination has not yet been described for A. phagocytophilum. None-the-less, this relatively simple experiment yielded multiple candidate genes of interest for further investigation.

After narrowing the initial bioinformatic and iTRAQ list of candidate genes to six, we investigated the ability of these proteins to be secreted by the bacterium. For A. phagocytophilum, the most well characterized secretion mechanism is that of the T4SS. Because of this, we focused on whether or not these proteins could be secreted by a T4SS. As an obligate intracellular bacterium that resides solely in membrane-bound vacuoles of its host cells, A. phagocytophilum-secreted proteins very likely first enter the cytosol before translocation to the nucleus, but are unlikely to be detected outside of the host cell owing to the intracellular vacuolar membranes accessible to the bacterium. Thus, the C. burnetii Dot/Icm T4SS was used as a surrogate delivery system because C. burnetii is capable of being transfected easily when cultivated in axenic medium but resides within host cell vacuoles when cultivated in mammalian cells. The Dot/Icm secretion system is compatible with that of A. phagocytophilum and, unless cultivated in specific axenic medium, C. burnetii is also an obligate intracellular bacterium residing within membrane-bound vacuoles. Using fusions with B. pertussis CyaA, one of six A. phagocytophilum candidate nuclear-localizing proteins was identified as a T4SS substrate. The remaining 5 did not appear to be secreted by the Dot/Icm system. Using SignalP 4.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/), we determined the presence of putative Sec1 secretion signals in the genes encoding APH_0382, APH_0385, and APH_0455 (all HGE-14-like); experimental confirmation of this secretion mechanism was not further attempted.

Interestingly, APH_0382, APH_0385, and APH_0455 were shown to be differentially expressed between mammalian and tick cells. The transcription of each of these proteins was approximately 2.9–3.3-fold greater in HL-60 cells than ISE6 (tick) cells (Nelson et al., 2008). This suggests that these HGE-14-like proteins likely play a role in establishing or maintaining infection in mammalian cells. In fact, differential transcription of A. phagocytophilum genes plays a role in the life cycle of the bacterium in mammalian and tick cells (Wang et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2008; Troese et al., 2011; Mastronunzio et al., 2012). APH_0784 (DNA binding protein HU), and APH_0292 (50S ribosomal protein L5) are among the 20 most abundant proteins expressed in infected I. scapularis salivary glands (Mastronunzio et al., 2012), and both were found in nuclear lysates of infected HL-60 cells, yet predicted to localize to the mitochondrion and cytosol, respectively. We also identified the transcriptional regulator of p44/msp2 genes, ApxR (APH_0515; Wang et al., 2007) in nuclear lysates from A. phagocytophilum infected HL-60 cells, but at a low unused ProtScore. As ApxR was unable to translocate to the nuclei of HEK293 cells, its presence indicates the potential for low level cytoplasmic contamination in the nuclear preparations. However, the overall level of cytoplasmic contamination is likely to be low since the most abundant A. phagocytophilum proteins in the P44/Msp2 family (Wang et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2008; Mastronunzio et al., 2012) were not abundant in nuclear lysates. Finally, APH_1235 is characterized as a specific marker of dense core infectious A. phagocytophilum (Troese et al., 2011). It is among the 20 most abundantly-expressed proteins in tick salivary glands (Mastronunzio et al., 2012), is significantly upregulated in dense core cells with HL-60 cell infection (Troese et al., 2011), and is believed to facilitate tick to mammal transmission. While predicted to localize to the nucleus by ProtComp v.6 and identified in infected HL-60 cell nuclear lysates, published data demonstrate the lack of nuclear localization (Troese et al., 2011). Moreover, it lacked a recognized NLS and the iTRAQ unused score was low, suggesting low-level contamination from the host cytosol.

APH_0455, a HGE-14 protein, is of particular interest owing to its utilization of the T4SS to enter the cell and its translocation into the nucleus where it forms small aggregates and clusters dispersed unevenly throughout the nucleoplasm. APH-0455 is one of several HGE-14 proteins predicted to enter the nucleus, and APH-0455 has been described to have transmembrane domains that would predict it to be a type II membrane protein, and possesses 4 conserved 41 amino acid repeats followed by 2 similar truncated repeats (Lodes et al., 2001). This repeat region overlaps a region with a conserved Med15/ARC15 (pfam09606) domain. Med15/ARC105 domains are found as part of a family of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs), transcription activators that regulate genes involved in cholesterol and fatty acid homeostasis. In humans, SREBPs bind CREB-binding protein (CBP)/p300 acetyltransferase that in turn affect chromatin structure and gene transcription (Yang et al., 2006). Whether APH_0455 plays a role in these critical pathways for A. phagocytophilum survival needs to be determined (Lin and Rikihisa, 2003).

Because of the candidate proteins' abilities to act as T4SS or Sec1 substrates and to localize to the nucleus, we sought to determine if they played a role in altering the phenotype of HL-60 cells, a commonly used cell model for A. phagocytophilum infection. Unfortunately, transfection of HL-60 cells with a variety of methods inconsistently altered oxidative burst capacity, and often the vehicle controls and transfection reagents were enough to abrogate responses. Despite the variable responses, we observed trends toward reduction of oxidative burst (Figure 3). Despite these trends, we cannot currently conclude with certainty that these effectors play a role in limiting oxidative burst as shown for AnkA (Banerjee et al., 2000).

For each of the A. phagocytophilum proteins that localized to the nucleus of HEK-293T and PLB-985 cells, it would be important confirm their presence in the nuclei of A. phagocytophilum- infected cells visually or biochemically, and to potentially assess the effects of their absence in A. phagocytophilum among Himar1 transposase libraries (Nelson et al., 2008; Troese et al., 2011). Additionally, future studies will examine their role in transcriptional and functional changes in differentiated HL-60 cells, the preferred model for A. phagocytophilum-directed neutrophil reprogramming. Such studies will focus on transcriptional responses, functional assays and, given the role that AnkA plays during the course of infection, studies of nuclear protein-protein, DNA-protein, and RNA-protein interactions. The screening techniques modeled here using A. phagocytophilum will allow for a more focused approach to identify potential nucleomodulins and could facilitate studies of microbial nucleomodulin manipulation of host cell transcriptional programs.

These techniques are not limited to the A. phagocytophilum genome but can also be applied to other intracellular bacteria. Using the same bioinformatics approaches (Supplemental Methods, Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Tables 1, 2), candidate genes were identified for other pathogens including, but not limited to: Chlamydia trachomatis, Coxiella burnetii, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Yersinia pestis, Legionella pneumophila, Francisella tularensis, and Listeria monocytogenes. Identification of new nucleomodulins in any one of these pathogens could add further insight as to how bacteria modulate their host cells and cause aberrant transcriptional reprogramming.

Conclusion

We used a combination of bioinformatic screens and iTRAQ in vitro identification of potential nuclear-translocated proteins to stratify and rapidly identify candidate nucleomodulins in A. phagocytophilum, an approach easily applied to other intracellular pathogens. By combining data gathered from bioinformatics prediction tools and iTRAQ, 50 A. phagocytophilum proteins were identified as potential nucleomodulins. Of the 50, we confirmed that six proteins were capable of localizing to the nucleus on their own, including APH_0455 that is also a T4SS substrate. The identification of novel nuclear translocated proteins provides additional support for the concept of nucleomodulin-mediated reprogramming of cellular functions that improve microbial fitness by promoting extended intracellular survival and more opportunities for transmission.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant R01AI044102 (J. Stephen Dumler) from the US National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and by subaward PO #SR00000759 (to Jose C. Garcia-Garcia) from Region III Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for Excellence grant U54 AI057168 from the NIAID (M. M. Levine, PI). The authors would like thank Paul Beare, Ph.D. and Charles Larson (Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, Hamilton, MT USA) for advice and performance of the T4SS assays; Kristen Rennoll-Bankert, Ph.D. (University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD USA) for technical assistance and support with cloning, expression and oxidative burst assays; Carlos Borroto, M.S., and Wan Hsin (Cindy) Chen, M.S. (Johns Hopkins University) for assistance with cloning; and Robert Cole, Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) A. B. Mass Spectrometry/Proteomic Facility for help with iTRAQ experiments and analyses.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00055/abstract

References

- Al-Khedery B., Lundgren A. M., Stuen S., Granquist E. G., Munderloh U. G., Barbet C. M., et al. (2012). Structure of the type IV secretion system in different strains of Anaplasma phagocytophilum. BMC Genomics 13:678. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R., Anguita J., Roos D., Fikrig E. (2000). Cutting edge: infection by the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis prevents the respiratory burst by down-regulating gp91phox. J. Immunol. 164, 3946–3949. 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.3946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare P. A., Howe D., Cockrell D. C., Omsland A., Hansen B., Heinzen R. A. (2009). Characterization of a Coxiella burnetii ftsZ mutant generated by Himar1 transposon mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 191, 1369–1381. 10.1128/JB.01580-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjesson D. L., Kobayashi S. D., Whitney A. R., Voyich J. M., Argue C. M., Deleo F. R. (2005). Insights into pathogen immune evasion mechanisms: Anaplasma phagocytophilum fails to induce an apoptosis differentiation program in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 174, 6364–6372. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyon J. A., Chan W. T., Galan J., Roos D., Fikrig E. (2002). Repression of rac2 mRNA expression by Anaplasma phagocytophila is essential to the inhibition of superoxide production and bacterial proliferation. J. Immunol. 169, 7009–7018. 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.7009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyon J. A., Fikrig E. (2006). Mechanisms of evasion of neutrophil killing by Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 13, 28–33. 10.1097/01.moh.0000190109.00532.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caturegli P., Asanovich K. M., Walls J. J., Bakken J. S., Madigan J. E., Popov V. L., et al. (2000). ankA: an Ehrlichia phagocytophila group gene encoding a cytoplasmic protein antigen with ankyrin repeats. Infect. Immun. 68, 5277–5283. 10.1128/IAI.68.9.5277-5283.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Severo M. S., Sakhon O. S., Choy A., Herron M. J., Pedra F. R., et al. (2012). Anaplasma phagocytophilum dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase 1 affects host-derived immunopathology during microbial colonization. Infect. Immun. 80, 3194–3205. 10.1128/IAI.00532-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. S., Park J. T., Dumler J. S. (2005). Anaplasma phagocytophilum delay of neutrophil apoptosis through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal pathway. Infect. Immun. 73, 8209–8218. 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8209-8218.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnes P., Hoglund A. (2004). Predicting protein subcellular localization: past, present, and future. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2, 209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning Hotopp J. C., Lin M., Madupu R., Crabtree J., Angiuoli S. V., Eisen J. A., et al. (2006). Comparative genomics of emerging human ehrlichiosis agents. PLoS Genet. 2:e21. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison M. A., Thurman G. W., Ambruso D. R. (2012). Phox activity of differentiated PLB-985 cells is enhanced, in an agonist specific manner, by the PLA2 activity of Prdx6-PLA2. Eur. J. Immunol. 42, 1609–1617. 10.1002/eji.201142157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsheim R. F., Herron M. J., Nelson C. M., Burkhardt N. Y., Barbet A. F., Kurtti T. J., et al. (2006). Transformation of Anaplasma phagocytophilum. BMC Biotechnol. 6:42. 10.1186/1472-6750-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Garcia J. C., Barat N. C., Trembley S. J., Dumler J. S. (2009a). Epigenetic silencing of host cell defense genes enhances intracellular survival of the rickettsial pathogen Anaplasma phagocytophilum. PLoS Pathog. 5:488. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Garcia J. C., Rennoll-Bankert K. E., Pelly S., Milstone A. M., Dumler J. S. (2009b). Silencing of host cell CYBB gene expression by the nuclear effector AnkA of the intracellular pathogen Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Infect. Immun. 77, 2385–2391. 10.1128/IAI.00023-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardy J. L., Laird M. R., Chen F., Rey S., Walsh C. J., Ester M., et al. (2005). PSORTb v.2.0: expanded prediction of bacterial protein subcellular localization and insights gained from comparative proteome analysis. Bioinformatics 21, 617–623. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman J. L., Nelson C., Vitale B., Madigan J. E., Dumler J. S., Kurtti T. J., et al. (1996). Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 209–215. 10.1056/NEJM199601253340401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks G. R., Raikhel N. V. (1995). Protein import into the nucleus: an integrated view. Ann. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 11, 155–188. 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.001103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund A., Donnes P., Blum T., Adolph H. W., Kohlbacher O. (2006). MultiLoc: prediction of protein subcellular localization using N-terminal targeting sequences, sequence motifs and amino acid composition. Bioinformatics 22, 1158–1165. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IJdo J. W., Carlson A. C., Kennedy E. L. (2007). Anaplasma phagocytophilum AnkA is tyrosine-phosphorylated at EPIYA motifs and recruits SHP-1 during early infection. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 1284–1296. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00871.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson C. L., Beare P. A., Howe D., Heinzen R. A. (2013). Coxiella burnetii effector protein subverts clathrin-mediated vesicular trafficking for pathogen vacuole biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E4770–E4779. 10.1073/pnas.1309195110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., den Dulk-Ras A., Hooykaas P. J., Rikihisa Y. (2007). Anaplasma phagocytophilum AnkA secreted by type IV secretion system is tyrosine phosphorylated by Abl-1 to facilitate infection. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 2644–2657. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00985.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Rikihisa Y. (2003). Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum lack genes for lipid A biosynthesis and incorporate cholesterol for their survival. Infect. Immun. 71, 5324–5331. 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5324-5331.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodes M. J., Mohamath R., Reynolds L. D., McNeill P., Kolbert C. P., Bruinsma E. S., et al. (2001). Serodiagnosis of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by using novel combinations of immunoreactive recombinant proteins. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 2466–2476. 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2466-2476.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronunzio J. E., Kurscheid S., Fikrig E. (2012). Postgenomic analyses reveal Development of infectious Anaplasma phagocytophilum during transmission from ticks to mice. J Bacteriol. 194, 2238–2247. 10.1128/JB.06791-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair R., Carter P., Rost B. (2003). NLSdb: database of nuclear localization signals. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 31, 397–399. 10.1093/nar/gkg001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. M., Herron M. J., Felsheim R. F., Schloeder B. R., Grindle S. M., Chavez A. O., et al. (2008). Whole geonme transcription profiling of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in human and tick host cells by tiling array analysis. BMC Genomics 9:364. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi N., Zhi N., Lin Q., Rikihisa Y. (2002). Characterization and transcriptional analysis of gene clusters for a type IV secretion machinery in human granulocytic and monocytic ehrlichiosis agents. Infect. Immun. 70, 2128–2138. 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2128-2138.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Kim K. J., Choi K. S., Grab D. J., Dumler J. S. (2004). Anaplasma phagocytophilum AnkA binds to granulocyte DNA and nuclear proteins. Cell. Microbiol. 6, 743–751. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedruzzi E., Fay M., Elbim C., Gaudry M., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A. (2002). Differentiation of PLB-985 myeloid cells into mature neutrophils, shown by degranulation of terminally differentiated compartments in response to N-formyl peptide and priming of superoxide anion production by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Br. J. Haematol. 117, 719–726. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennoll-Bankert K. E., Dumler J. S. (2012). Lessons from Anaplasma phagocytophilum: chromatin remodeling by bacterial effectors. Infect. Dis. Drug. Targets 12, 380–387. 10.2174/187152612804142242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennoll-Bankert K. E., Sinclair S. H., Lichay M. A., Dumler J. S. (2014). Comparison and characterization of granulocyte cell models for Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection. Pathog. Dis. 71, 55–64. 10.1111/2049-632X.12111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikihisa Y., Lin M., Niu H. (2010). Type IV secretion in the obligatory intracellular bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Cell. Microbiol. 12, 1213–1221. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01500.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S. H., Rennoll-Bankert K. E., Dumler J. S. (2014). Effector bottleneck: microbial reprogramming of parasitized host cell transcription by epigenetic remodeling of chromatin structure. Front. Genet. 5:274. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troese M. J., Kahlon A., Ragland S. A., Ottens A. K., Ojogun N., Carlyon J. A., et al. (2011). Proteomic analysis of Anaplasma phagocytophilum during infection of human myeloid cells identifies a protein that is pronouncedly upregulated on the infectious dense-cored cell. Infect. Immun. 79, 4696–4707. 10.1128/IAI.05658-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voth D. E., Beare P. A., Howe D., Sharma U. M., Samoilis G., Cockrell D. C., et al. (2011). The Coxiella burnetii cryptic plasmid is enriched in genes encoding type IV secretion system substrates. J. Bacteriol. 193, 1493–1503. 10.1128/JB.01359-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Cheng Z., Zhang C., Kikuchi T., Rikihisa Y. (2007). Anaplasma phagocytophilum p44 mRNA expression is differentially regulated in mammalian and tick host cells: involvement of the dna binding protein ApxR. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8651–8659. 10.1128/JB.00881-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Vought B. W., Satterlee J. S., Walker A. K., Jim Sun Z. Y., Watts J. L., et al. (2006). An ARC/Mediator subunit required for SREBP control of cholesterol and lipid homeostasis. Nature 442, 700–704. 10.1038/nature04942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.