Abstract

Objectives

It is still debated if pre-existing minority drug-resistant HIV-1 variants (MVs) affect the virological outcomes of first-line NNRTI-containing ART.

Methods

This Europe-wide case–control study included ART-naive subjects infected with drug-susceptible HIV-1 as revealed by population sequencing, who achieved virological suppression on first-line ART including one NNRTI. Cases experienced virological failure and controls were subjects from the same cohort whose viraemia remained suppressed at a matched time since initiation of ART. Blinded, centralized 454 pyrosequencing with parallel bioinformatic analysis in two laboratories was used to identify MVs in the 1%–25% frequency range. ORs of virological failure according to MV detection were estimated by logistic regression.

Results

Two hundred and sixty samples (76 cases and 184 controls), mostly subtype B (73.5%), were used for the analysis. Identical MVs were detected in the two laboratories. 31.6% of cases and 16.8% of controls harboured pre-existing MVs. Detection of at least one MV versus no MVs was associated with an increased risk of virological failure (OR = 2.75, 95% CI = 1.35–5.60, P = 0.005); similar associations were observed for at least one MV versus no NRTI MVs (OR = 2.27, 95% CI = 0.76–6.77, P = 0.140) and at least one MV versus no NNRTI MVs (OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.12–5.18, P = 0.024). A dose–effect relationship between virological failure and mutational load was found.

Conclusions

Pre-existing MVs more than double the risk of virological failure to first-line NNRTI-based ART.

Keywords: minority drug-resistant HIV-1 variants, CHAIN, antiretroviral therapy, European multicentre study

Introduction

Antiretroviral drug resistance testing is one of the mainstays of the clinical management of HIV-1 infection1 and is essential to inform public health strategies to combat the HIV/AIDS epidemic.2 Population sequencing of plasma viruses only detects the most abundant viral variants infecting each subject.3,4 Thereby, clinicians might miss potentially relevant information when making treatment decisions and public health estimations underestimate the burden of HIV-1 drug resistance. Next-generation sequencing platforms detect minority viral variants with higher sensitivity, but the clinical relevance of this is under discussion.

NNRTIs are often prescribed as first-line ART as efavirenz is a recommended third drug in all treatment guidelines and nevirapine is one of the most affordable drugs in resource-limited settings.5–8 These drugs are highly efficacious, but have a low genetic barrier to resistance; even HIV-1 with a single mutation can become fully resistant to NNRTIs.1 The small impact of most NNRTI resistance mutations on HIV-1 replicative capacity allows their persistence in the virus population of the infected subjects9 and their transmission to newly infected subjects. Using population sequencing, between 5% and 15% of new HIV-1 infections in Europe and the USA occur with an NNRTI-resistant virus.10,11 An additional fraction of ART-naive subjects harbour minority drug-resistant variants, which could also be transmitted or be spontaneously generated in the absence of ART exposure.12–14

The best available evidence of the clinical relevance of minority NNRTI-resistant HIV-1 variants to date is a systematic review and pooled analysis of 10 published studies including 1263 ART-naive subjects who initiated first-line NNRTI-containing ART with drug-susceptible HIV-1 according to population sequencing.15 In that study, detection of pre-existing minority drug-resistant HIV-1 variants (MVs) more than doubled the risk of virological failure to first-line ART, showing a direct dose–effect relationship between the level of MVs and the risk of virological failure. This analysis, however, pooled studies with heterogeneous designs, different MV detection techniques and inconsistent results.

To further clarify the impact of MVs on the virological outcomes of first-line NNRTI-containing ART in the light of these previous data, we designed a large European case–control study including standard operating procedures for data collection, centralized cDNA synthesis and 454 pyrosequencing and duplicate 454 bioinformatic analysis of MVs, all blinded for clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study objectives

This study sought to investigate the ability of a single, pre-ART, ultrasensitive HIV-1 genotypic test using 454 pyrosequencing (454 Life Sciences/Roche Diagnostics) to predict virological failure to first-line ART including two NRTIs and one NNRTI. Additional objectives were to evaluate the consistency of the observations across different subsets of subjects and to assess the presence of a dose–response relationship between mutational load and risk of virological failure.

Study design and participants

This was a case–control study nested within seven prospective European HIV-1 observational cohorts: Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS), EuroSIDA Study in EuroCoord (EuroSIDA), Italian Cohort of Antiretroviral-Naive Patients (ICONA), German Competence Network (KompNet), Arevir Platform, ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort (Aquitaine) and Royal Free Hospital (RFH) cohort. Clinical data were extracted from these cohorts using a standard operating procedure (see the Supplementary data available at JAC Online).

The study population included ART-naive subjects initiating ART with two NRTIs plus one NNRTI and achieving a viral load ≤50 copies/mL within the first 6 months following ART initiation. In addition, subjects had to have one stored plasma sample with HIV-1 RNA levels ≥10 000 copies/mL within 6 months prior to ART initiation and ≥3 months of virological follow-up after achieving virological suppression. Subjects with any pre-ART IAS-USA (March 2013)1 NNRTI or NRTI resistance mutation detected by population sequencing or with NNRTI/NRTI mutations at a frequency >25% by 454 pyrosequencing were excluded.

Cases were subjects developing virological failure, defined as two consecutive HIV-1 RNA measurements >200 copies/mL after achieving HIV-1 RNA ≤50 copies/mL. Virological failure had to occur while the person was still receiving the initial NNRTI therapy. The first of the two HIV-1 RNA values >200 copies/mL was taken as time of the event. Controls were subjects selected from the same cohort whose HIV-1 RNA was still ≤200 copies/mL at a time matching the time of virological failure for the corresponding case. A minimum of two matched controls were chosen for every case. We applied the concept of case–control studies of dynamic populations for our case–control sampling;16 thus, the same patient can be included in several case–control sets.

Plasma sample processing, RT–PCR and 454 pyrosequencing

Archived plasma samples with HIV-1 RNA levels ≥10 000 copies/mL and collected from the different cohorts within 6 months prior to ART initiation were shipped to Utrecht Medical Centre (Utrecht, The Netherlands), where cDNA was generated using random hexamers as primers. cDNAs were then shipped to the Institut für Immunologie und Genetik (Kaiserslautern, Germany), where 454 amplicons were immediately prepared and pyrosequenced in batches of 80 samples each in a 454 FLX Genome Sequencer using Titanium chemistry. Amplicons used for this analysis included amplicons A (protease), B, C and D (reverse transcriptase) from the 454/Roche HIV-1 Genotyping Kit v2 plus one additional amplicon designed specifically for this study (amplicon E), which covered the main NNRTI mutations (Figure S1). Of note, amplicon A was amplified but not sequenced, as protease data were considered not relevant for the present study. cDNA synthesis and 454 processing were performed blinded for clinical outcomes.

Data analysis

454 pyrosequencing sff files were analysed in parallel at the IrsiCaixa AIDS Research Institute (Badalona, Catalonia, Spain) and University Hospital Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland), blinded for clinical outcomes. Sequences were demultiplexed using both 5′ and 3′ multiple identifier barcodes. Roche's proprietary Amplicon Variant Analyzer software version 2.7 was used to call drug resistance mutations, based on the consensus alignment information for each sample, using the HIV-1 HXB2 clonal sequence (GenBank ID: K03455.1) as reference. A variant list containing all IAS-USA drug resistance mutations1 was used. Mutants had to be well balanced (their frequency in forward and reverse reads had to be comprised within one log ratio) and to have been identified from a total of ≥300 reads to be considered evaluable; otherwise, the codon was considered WT. A sample was defined to have a detected MV if 1%–25% of the virus population showed that variant. The analyses of both centres showed identical results (Figure S2).

The prevalence of detected MVs in cases and controls was compared using the χ2 test. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to estimate ORs of virological rebound according to the prevalence of MVs. Separate models were constructed for: (i) the presence of at least one IAS-USA 2013 reverse transcriptase inhibitor (RTI) MV; (ii) the presence of at least one IAS-USA 2013 NRTI MV; (iii) the presence of at least one IAS-USA 2013 NNRTI MV; and (iv) mutational load. The latter was calculated by multiplying the mutant frequency in the virus population by the HIV-1 RNA levels detected in the same sample and expressed as mutant copy number/mL. If more than one MV was detected in the same subject, the exposure variable ‘mutational load’ was calculated by adding the copy number/mL of all mutants detected. For the analysis of risk, mutational load was evaluated as a categorical variable, i.e. 0, 400–1000 and >1000 copies/mL, cut-offs chosen a priori on the basis of previously published results.15 All multivariable estimates were adjusted for factors included in the multivariable models shown in Table 2. Additional sensitivity analyses were performed by including 245 unique samples (each patient was included in the analysis only once) and after excluding sequences containing aligned in-frame stop codons.

Table 2.

Factors associated with virological failure

| Cases, N = 76 | Controls, N = 184 | ORs of viral rebound >200 RNA copies/mL plasma |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P | adjusteda OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| male | 54 (71.1) | 153 (83.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| female | 22 (28.9) | 31 (16.8) | 2.01 (1.07–3.77) | 0.029 | 1.61 (0.73–3.53) | 0.239 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| non-black | 69 (90.8) | 182 (98.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| black | 7 (9.2) | 2 (1.1) | 9.23 (1.87–45.53) | 0.006 | 13.62 (2.25–82.49) | 0.004 |

| HIV-1 subtype, n (%) | ||||||

| B | 52 (68.4) | 139 (75.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| non-B | 24 (31.6) | 45 (24.5) | 1.43 (0.79–2.57) | 0.238 | 1.28 (0.64–2.59) | 0.484 |

| Calendar year of starting ART, median (IQR) | ||||||

| per more recent | 2003 (2001–05) | 2004 (2002–06) | 0.88 (0.79–0.97) | 0.010 | 0.85 (0.72–1.01) | 0.072 |

| Time from sample to ART initiation, median (IQR) | ||||||

| per month longer | 2.97 (1.21–5.02) | 1.61 (0.00–3.31) | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 0.038 | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 0.006 |

| HIV-1 RNA at NNRTI initiation, median (IQR) | ||||||

| per log10 copies/mL higher | 4.85 (4.54–5.30) | 4.91 (4.50–5.36) | 0.94 (0.58–1.54) | 0.817 | 1.26 (0.68–2.33) | 0.466 |

| NNRTI started, n (%) | ||||||

| nevirapine | 21 (27.6) | 21 (11.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| efavirenz | 55 (72.4) | 163 (88.6) | 0.34 (0.17–0.66) | 0.002 | 0.43 (0.18–1.02) | 0.055 |

| NRTI backbone started, n (%) | ||||||

| recommended: ABC/3TC or TDF/FTC | 17 (22.4) | 64 (34.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| alternative: ZDV/3TC or TDF/3TC | 36 (47.4) | 96 (52.2) | 1.41 (0.73–2.73) | 0.304 | 0.84 (0.30–2.32) | 0.732 |

| not recommended | 23 (30.3) | 24 (13.0) | 3.61 (1.65–7.89) | 0.001 | 2.39 (0.74–7.69) | 0.145 |

| Detection of ≥1 IAS-USA MV prior to ART, any RTI, n (%) | ||||||

| no | 52 (68.4) | 153 (83.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| yes | 24 (31.6) | 31 (16.8) | 2.28 (1.23–4.23) | 0.009 | 2.75 (1.35–5.60) | 0.005 |

| Detection of ≥1 IAS-USA NRTI MV prior to ART, n (%) | ||||||

| no | 68 (89.5) | 175 (95.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| yes | 8 (10.5) | 9 (4.9) | 2.29 (0.85–6.17) | 0.102 | 2.27 (0.76–6.77) | 0.140 |

| Detection of ≥1 IAS-USA NNRTI MV prior to ART, n (%) | ||||||

| no | 57 (75.0) | 158 (85.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| yes | 19 (25.0) | 26 (14.1) | 2.03 (1.04–3.94) | 0.037 | 2.41 (1.12–5.18) | 0.024 |

| Mutational load (RNA copies/mL), n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 52 (68.4) | 153 (83.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 400–1000 | 6 (7.9) | 8 (4.3) | 2.21 (0.73–6.66) | 0.160 | 2.58 (0.68–9.73) | 0.162 |

| >1000 | 18 (23.7) | 23 (12.5) | 2.30 (1.15–4.60) | 0.018 | 2.81 (1.26–6.24) | 0.011 |

IAS-USA, IAS-USA HIV-1 drug resistance mutation list (March 2013 update); ABC, abacavir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; 3TC, lamivudine; FTC, emtricitabine; ZDV, zidovudine.

aAdjusted for calendar year of starting first-line ART, time from sample to ART initiation, viral load at ART initiation, NRTI pair started, NNRTI started, ethnicity, HIV-1 subtype, gender and cohort study.

Results

Subjects' disposition

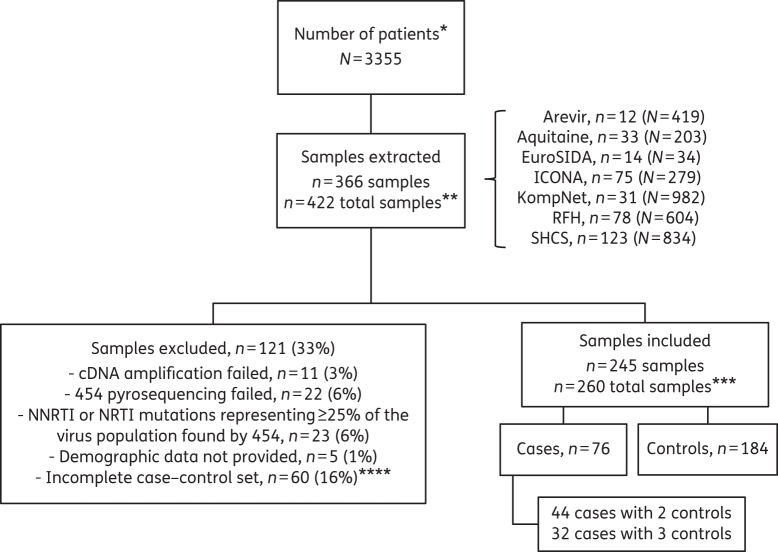

Clinical data were obtained from a total of 3355 ART-naive patients from seven prospective European HIV-1 observational cohorts, all started ART containing two NRTIs and efavirenz or nevirapine, achieving viral suppression ≤50 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL plasma, and providing a genotypic HIV-1 drug resistance test prior to first-line ART, leading to the extraction of 366 patients (Figure 1): 12 from Arevir, 33 from Aquitaine, 14 from EuroSIDA, 75 from ICONA, 31 from KompNet, 78 from the RFH cohort and 123 from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. One hundred and twenty-one (33%) samples were excluded from downstream analyses due to the following reasons: cDNA synthesis failed in 11 (3%) samples; 454 sequencing failed in 22 (6%) samples; NNRTI mutations were found at ≥25% frequency by 454 pyrosequencing in 23 (6%) pre-ART samples; demographic data could not be provided by the cohort in 5 (1%) samples; and an additional 60 (16%) had to be excluded due to incomplete case–control sets. The 245 included and 116 excluded patients (for whom demographic data were available) showed no differences in terms of age, gender, ethnicity and mode of transmission. In contrast, viral load was significantly lower in the excluded patients compared with the included patients [4.77 (4.42–5.11) versus 4.91 (4.58–5.32), median (IQR), log10 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL plasma, P = 0.003]. This was caused by the fact that cDNA synthesis or 454 pyrosequencing failed predominantly in those samples with lower viral loads.

Figure 1.

Subject disposition and scheme of the study design. MVs were analysed by next-generation sequencing in plasma samples with HIV-1 RNA levels ≥10 000 copies/mL collected within 6 months prior to ART initiation. *ART-naive patients in the cohorts starting ART containing two NRTIs and one NNRTI (efavirenz or nevirapine), achieving viral suppression ≤50 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL plasma and providing a genotypic HIV-1 drug resistance test prior to first-line ART. **Three hundred and sixty-six samples from 366 different patients were extracted from the different cohorts. Since several patients were matched controls in more than one case–control set, the total number of samples was 422. ***The main analyses were performed on 260 samples; a sensitivity analysis was performed on 245 unique samples. ****The exclusion of 61 patients due to technical challenges, NNRTI or NRTI mutations representing ≥25% of the virus population or missing demographic data led to the exclusion of an additional 60 samples since certain case–control sets were subsequently incomplete.

Applying the concept of case–control studies of dynamic populations for our case–control sampling,16 i.e. allowing the same person/sample to be used as control for more than one case, 260 samples (76 cases and 184 matched controls) were analysed. There were 44 cases with two matched controls and 32 cases with three matched controls. In a sensitivity analysis, we used the 245 unique samples.

Subjects' characteristics

Subjects were mostly male, Caucasian and infected through sexual intercourse with mostly HIV-1 subtype B (Table 1). Their median age was 34 years and the median calendar year of ART initiation was 2003. They began ART with a median CD4+ count of 259 cells/mm3 counts and median HIV-1 RNA levels of 4.9 log copies/mL plasma. Most of them (83.9%) started with efavirenz. The NRTI backbone consisted of drugs currently considered alternative in treatment guidelines (zidovudine/lamivudine or tenofovir/lamivudine) in 50.8% and currently recommended NRTIs (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine or abacavir/lamivudine) in 31.2%; 18.1% began with NRTI combinations that are no longer recommended (e.g. including didanosine, stavudine, or tenofovir in combination with zidovudine). Baseline characteristics were evenly distributed between subjects with or without MVs with two exceptions: MVs were less frequently observed in women (P = 0.05), slightly more frequent in subjects receiving currently recommended NRTIs and slightly less frequent in subjects receiving currently alternative NRTIs (P = 0.04).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population according to detection of MVs in plasma samples collected prior to first-line NNRTI-based ART

| ≥1 IAS MV, N = 55 | No MVs, N = 205 | P | Total, N = 260 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.776 | |||

| median (IQR) | 36 (26–41) | 33 (24–43) | 34 (24–42) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.050 | |||

| female | 6 (10.9) | 47 (22.9) | 53 (20.4) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.143 | |||

| white | 39 (70.9) | 131 (63.9) | 170 (65.4) | |

| black | 3 (5.5) | 6 (2.9) | 9 (3.5) | |

| Asian | 2 (3.6) | 5 (2.4) | 7 (2.7) | |

| other | 11 (20.0) | 63 (30.7) | 74 (28.5) | |

| Mode of HIV transmission, n (%) | 0.382 | |||

| MSM | 27 (49.1) | 77 (37.6) | 104 (40.0) | |

| heterosexual | 13 (23.6) | 82 (40.0) | 95 (36.5) | |

| intravenous drug use | 6 (10.9) | 26 (12.7) | 32 (12.3) | |

| other/unknown | 9 (16.4) | 20 (9.8) | 29 (11.2) | |

| HIV-1 subtype, n (%) | 0.276 | |||

| A | 1 (1.8) | 7 (3.4) | 8 (3.1) | |

| B | 40 (72.7) | 151 (73.7) | 191 (73.5) | |

| C | 3 (5.5) | 10 (4.9) | 13 (5.0) | |

| D | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | |

| F | 2 (3.6) | 3 (1.5) | 5 (1.9) | |

| G/J | 3 (5.5) | 7 (3.4) | 10 (3.8) | |

| CRF01_AE | 0 (0.0) | 9 (4.4) | 9 (3.5) | |

| CRF01_AG | 4 (7.3) | 6 (2.9) | 10 (3.8) | |

| Calendar year of starting NNRTI | 0.250 | |||

| median (IQR) | 2004 (2002–06) | 2003 (2003–06) | 2003 (2002–06) | |

| Time from sample to ART initiation (months) | 0.310 | |||

| median (IQR) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | |

| CD4+ count at ART initiation (cells/mm3) | 0.717 | |||

| median (IQR) | 261 (196–326) | 258 (173–371) | 259 (176–353) | |

| HIV-1 RNA at ART initiation (log10 copies/mL) | 0.995 | |||

| median (IQR) | 4.92 (4.55–5.36) | 4.90 (4.49–5.32) | 4.91 (4.58–5.33) | |

| NNRTI started, n (%) | 0.962 | |||

| nevirapine | 9 (16.4) | 33 (16.1) | 42 (16.2) | |

| efavirenz | 46 (83.6) | 172 (83.9) | 218 (83.8) | |

| NRTI pair started, n (%) | 0.040 | |||

| recommended: ABC/3TC or TDF/FTC | 19 (34.5) | 62 (30.2) | 81 (31.2) | |

| alternative: ZDV/3TC or TDF/3TC | 26 (47.3) | 106 (51.7) | 132 (50.8) | |

| not recommended | 10 (18.2) | 37 (18.0) | 47 (18.1) | |

| Cohort, n (%) | 0.340 | |||

| Arevir | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.9) | 6 (2.3) | |

| Aquitaine | 3 (5.5) | 25 (12.2) | 28 (10.8) | |

| EuroSIDA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ICONA | 11 (20.0) | 40 (19.5) | 51 (19.6) | |

| KompNet | 5 (9.1) | 9 (4.4) | 14 (5.4) | |

| RFH | 12 (21.8) | 48 (23.4) | 60 (23.1) | |

| Swiss HIV Cohort Study | 24 (43.6) | 77 (37.6) | 101 (38.8) |

IAS-USA, IAS-USA HIV-1 drug resistance mutation list (March 2013 update); ABC, abacavir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; 3TC, lamivudine; FTC, emtricitabine; ZDV, zidovudine.

MVs

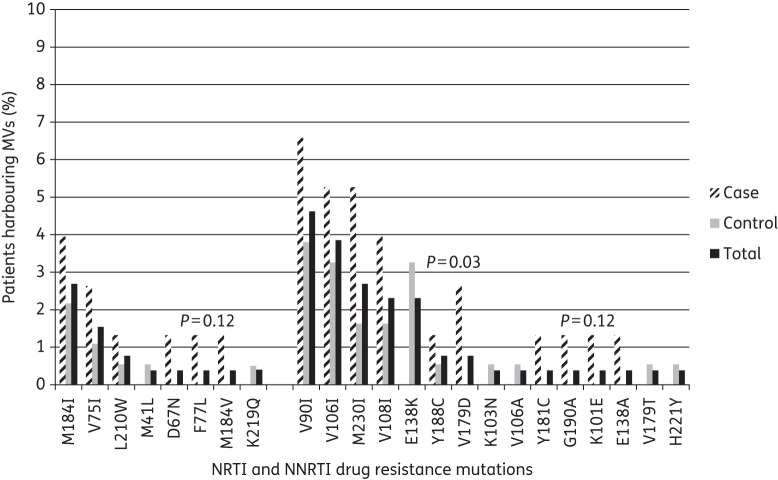

MVs were analysed by next-generation sequencing in plasma samples with a median of 4.91 log10 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL plasma collected 2 (IQR 0–4) months prior to ART initiation (Table 1). Due to amplicon overlap, all relevant amino acid positions in the reverse transcriptase were covered by ≥1000 sequence reads, with median coverage ranging from ≥1500 to 5000 sequence reads (Figure S3). MVs were detected in 55 (21%) subjects: 17 (7%) to NRTIs and 45 (17%) to NNRTIs at frequencies of 1.1%–24.4% (Table S1). Overall, MVs were more frequently observed in cases (24/76; 31.6%) than in controls (31/184; 16.8%) (χ2 test, P = 0.009; Table 2). All but three subjects with MVs harboured only one MV. The most frequently observed MVs were M184I (3%), V75I (1.5%) and L210W (1%) for NRTIs and V90I (5%), V106I (4%), M230I (3%), V108I (2%) and E138K (2%) for NNRTIs (Figure 2). The study was not powered to detect significant differences in the prevalence of individual mutations among groups.

Figure 2.

IAS-USA 2013 mutations detected as minority drug resistance mutations by case–control status. Only P values <0.2 are reported. Two hundred and forty-five unique samples were included.

Factors associated with virological failure

After adjusting for calendar year of starting first-line ART, time from sample to ART initiation, HIV-1 RNA levels at ART initiation, specific NRTI pair started, NNRTI started, ethnicity, HIV-1 subtype, gender and cohort of enrolment, detection of at least one IAS-USA 2013 MV conferring resistance to RTIs was associated with an increased risk of virological failure to first-line, NNRTI-containing ART [OR = 2.75 (95% CI 1.35–5.60), P = 0.005] (Table 2). Similar associations were observed for detection of at least one IAS-USA 2013 MV resistant to NNRTIs alone [OR = 2.41 (95% CI 1.12–5.18), P = 0.024] or NRTIs alone [OR = 2.27 (95% CI 0.76–6.77), P = 0.140] (Table 2), although the latter did not reach statistical significance.

There was a direct dose–effect relationship between the mutational load of MVs and risk of virological failure. Subjects with 400–1000 MV copies/mL plasma had an intermediate risk [OR = 2.58 (95% CI 0.68–9.73), P = 0.162] whereas those with >1000 MV copies/mL plasma had the highest risk [OR = 2.81 (95% CI 1.26–6.24), P = 0.011].

The magnitude of these associations was consistent in pre-specified groups stratified by baseline NNRTI or NRTI used as well as in the sensitivity analysis including 245 unique samples [OR for at least one IAS-USA RTI MV = 2.69 (95% CI 1.30–5.57), P = 0.008] (Table S2) and excluding sequences containing aligned in-frame stop codons [OR for at least one IAS-USA RTI MV = 1.89 (95% CI 0.88–4.04), P = 0.103] (Table S3).

Other factors associated with increased risk of virological failure included black ethnicity [OR = 13.62 (95% CI 2.25–82.49), P = 0.004] and time from sample to ART initiation [OR = 1.07 (95% CI 1.02–1.12) per month longer, P = 0.006].

Discussion

In this large European case–control study, detection of low-frequency mutations conferring resistance to RTIs was strongly associated with a >2-fold increased risk of virological failure in people initiating first-line ART with two NRTIs plus one NNRTI. This association was consistent regardless of the NRTI backbone started or whether nevirapine or efavirenz was commenced. Moreover, there was a significant dose–effect relationship between the mutational load of MVs and the risk of virological failure. Similar results were observed in the analyses focusing on the effect associated with the detection of at least one NNRTI or one NRTI mutation, although for the latter the association did not reach statistical significance.

This study confirms and extends previous observations15,17–21 and to date provides the highest degree of evidence available that low-frequency drug-resistant mutants do impair the efficacy of ART including the NNRTIs nevirapine or efavirenz plus two NRTIs. Interestingly, this was independent from the viral load prior to ART, which was not different in cases and controls. It is also the largest single study available using next-generation sequencing for HIV-1 drug resistance genotyping.

We defined virological failure as a confirmed viraemia rebound of >200 copies/mL after achieving HIV-1 RNA ≤50 copies/mL. This definition excluded subjects who never achieved HIV-1 RNA suppression and might have led to exclusion of people with NNRTI-resistant MVs most strongly associated with drug resistance, such as K103N and Y181C. Indeed, previous studies showed that MVs such as K103N and Y181C strongly predicted early virological failure and lack of HIV-1 RNA suppression.15,17 Thus, our study design might lead to an underestimation of the impact of MVs. However, we deliberately chose this definition to remove patients with poor adherence, a factor associated with both drug resistance and virological failure, which is difficult to control for in analysis of observational data.

To avoid heterogeneity related to minority drug-resistant HIV-1 variant testing, cDNA synthesis, 454 amplicon generation and 454 pyrosequencing were centralized in two highly experienced European centres, blinded for virological outcomes. Amplicon generation and sequencing is relatively complex with this platform and testing in laboratories with different degrees of expertise could have led to inconsistencies. Parallel analysis of raw 454 data in two independent laboratories blinded for clinical outcomes achieved 100% agreement, ruling out sequence interpretation biases.

The case–control design of this study does not allow a formal estimate of the incidence of virological failure in the cohorts, because the number of cases is fixed at the outset. Nevertheless, we detected MVs more frequently than anticipated (in 21% of subjects overall). In a previous pooled analysis of studies,15 14% of subjects infected with WT HIV-1 by population sequencing harboured minority NNRTI-resistant variants. The most prevalent mutations in our population were V90I, V106I and M230I for NNRTIs and M184I, V75I and L210W for NRTIs. Mutations V90I and V106I are polymorphic accessory mutations weakly selected by NNRTIs in vitro and in vivo. They contribute to reduced susceptibility to etravirine in combination with other mutations, but induce a small, if any, reduction in efavirenz or nevirapine susceptibility even if detected as majority variants.22 In a recent analysis of 4528 UK patients who commenced efavirenz or nevirapine with at least two NRTIs without major drug resistance mutations, polymorphisms at codons 90 (mostly V90I), 98 (mostly A98S) and 103 (mostly K103R) were each independently associated with increased risk of virological failure.23 In combination with other mutations, V106I may enhance the level of resistance to efavirenz.24 The other mutations detected in our study are well known to reduce NNRTI susceptibility. As our study was not powered to discern the effect of individual mutations on the efficacy of first-line, NNRTI-containing ART, it is uncertain whether any of the individual mutations detected exerted a direct effect on NNRTI susceptibility or, in contrast, were surrogate markers of other, perhaps more relevant NNRTI resistance mutations present in the virus population below the detection threshold of 454 pyrosequencing.

In our main analysis, we did not exclude sequences containing stop codons, which may be a marker of poor sequence quality. However, sequence quality or alignment problems were ruled out by visual inspection of alignments. In addition, mutants required a minimum coverage based on the Poisson probability to detect rare events25 and an even representation in forward and reverse reads to be considered real.26 Indeed, a sensitivity analysis excluding sequences with stop codons provided similar trends to those observed in the main analysis (Table S3), although trends are non-significant, pointing out a possible role of stop codon-containing sequences in resistance analysis. In fact, the most prevalent mutations in our study correspond to G-to-A mutations and could share a generation mechanism with stop codons, both resulting from APOBEC3G/F editing,27,28 which is not related to sequence quality. This phenomenon is being further investigated by our group.

As a limitation, we did not collect enough genotypic tests at virological failure to investigate whether the pre-ART MVs were enriched at viral rebound (Table S4). However, such a relationship might not be linear, as the fate of pre-ART variants may also be determined by the specific treatment received and by complex mutational interactions where not only resistance but also fitness and genetic barriers to resistance would play important roles. In previous studies in antiretroviral-naive subjects,21 NNRTI regimen choice and pre-existing minority NNRTI-resistant variants were both associated with the probability and type of resistance mutations detected after virological failure. Also, our study lacked a formal evaluation of ART adherence given that cohorts do not uniformly collect such data. In previous studies,19,20 the presence of minority NNRTI resistance mutations and NNRTI adherence were found to be independent predictors of virological failure, but also to modify each other's effects on virological failure. By including people who achieved viral suppression on their initial ART, we should have reduced the inclusion of poorly adherent subjects.

Other factors associated with virological failure in our study were black ethnicity and longer time from sample to ART initiation. Previous studies have linked black ethnicity with virological failure through impaired socioeconomic status and adherence29 and/or presence of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms associated with a slow metabolizer profile, which lead to increased neurotoxicity by efavirenz.30,31 The association between longer time from sample to ART initiation, again, might be a marker of poor adherence, overall quality of care or some other unrecognized factors. Indeed, it is conceivable that initiation of ART might be delayed in persons who are perceived to be potentially non-adherent. However, the magnitude of the OR is small and therefore this association is probably not clinically relevant.

In summary, this study confirms and extends previous reports and provides strong evidence that MVs in the reverse transcriptase impair the efficacy of first-line ART including efavirenz or nevirapine. Our findings, together with those previously published, suggest that ultrasensitive HIV-1 genotyping could have a role in improving the outcomes of ART including NNRTIs. Consequently, they also provide a rationale for including ultrasensitive genotyping in HIV-1 resistance surveillance programmes.

Members of the CHAIN Minority HIV-1 Variants Working Group

Roger Paredes (Institut de Recerca de la SIDA IrsiCaixa i Unitat VIH, Spain), Karin J. Metzner (University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland; Swiss HIV Cohort Study), Alessandro Cozzi-Lepri (University College London, UK; EuroSIDA), Rob Schuurman (University Medical Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands), Francoise Brun-Vezinet (Bichat University Hospital, Paris, France), Huldrych Günthard (University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland; Swiss HIV Cohort Study), Francesca Ceccherini-Silberstein (University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy; ICONA), Rolf Kaiser (University of Cologne, Germany; Arevir), Anna Maria Geretti (University of Liverpool, UK; RFH), Norbert Brockmeyer (Ruhr-Universität, Germany; KompNet) and Bernard Masquelier (Université Bordeaux, France; Aquitaine).

Members of the participating European study groups

Composition of the ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort and the Groupe d'Epidémiologie Clinique du SIDA en Aquitaine (GECSA)

Coordination: F. Dabis. Epidemiology and methodology: M. Bruyand, G. Chêne, F. Dabis, S. Lawson-Ayayi, R. Thiébaut and L. Wittkop. Infectious diseases and internal medicine: K. André, F. Bonnal, F. Bonnet, N. Bernard, L. Caunègre, C. Cazanave, J. Ceccaldi, I. Chossat, K. Courtaud, F. A. Dauchy, S. De Witte, M. Dupon, A. Dupont, P. Duffau, H. Dutronc, S. Farbos, V. Gaborieau, M. C. Gemain, Y. Gerard, C. Greib, M. Hessamfar, D. Lacoste, P. Lataste, E. Lazaro, M. Longy-Boursier, D. Malvy, J. P. Meraud, P. Mercié, E. Monlun, P. Morlat, D. Neau, A. Ochoa, J. L. Pellegrin, T. Pistone, M. C. Receveur, J. Roger Schmeltz, S. Tchamgoué, M. A. Vandenhende, M. O. Vareil and J. F. Viallard. Immunology: J. F. Moreau and I. Pellegrin. Virology: H. Fleury, M. E. Lafon, B. Masquelier, S. Reigadas and P. Trimoulet. Pharmacology: S. Bouchet, D. Breilh, M. Molimard and K. Titier. Drug monitoring: F. Haramburu and G. Miremont-Salamé. Data collection and processing: M. J. Blaizeau, M. Decoin, J. Delaune, S. Delveaux, C. D'Ivernois, C. Hanapier, O. Leleux, E. Lenaud, B. Uwamaliya-Nziyumvira and X. Sicard. Computing and statistical analysis: S. Geffard, F. Le Marec, V. Conte, A. Frosch, J. Leray, G. Palmer and D. Touchard (CREDIM-ISPED). Scientific committee: F. Bonnet, D. Breilh, G. Chêne, F. Dabis, M. Dupon, H. Fleury, D. Malvy, P. Mercié, P. Morlat, D. Neau, I. Pellegrin, J. L. Pellegrin, S. Bouchet, V. Gaborieau, D. Lacoste, S. Tchamgoué and R. Thiébaut.

Members of the EuroSIDA Cohort (national coordinators in parentheses)

Argentina: (M. Losso) and M. Kundro, Hospital J. M. Ramos Mejia, Buenos Aires. Austria: (N. Vetter), Pulmologisches Zentrum der Stadt Wien, Vienna; and R. Zangerle, Medical University Innsbruck, Innsbruck. Belarus: (I. Karpov) and A. Vassilenko, Belarus State Medical University, Minsk; V. M. Mitsura, Gomel State Medical University, Gomel; and O. Suetnov, Regional AIDS Centre, Svetlogorsk. Belgium: (N. Clumeck), S. De Wit and M. Delforge, Saint-Pierre Hospital, Brussels; E. Florence, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp; and L. Vandekerckhove, University Ziekenhuis Gent, Gent. Bosnia-Herzegovina: (V. Hadziosmanovic), Klinicki Centar Univerziteta Sarajevo, Sarajevo. Bulgaria: (K. Kostov), Infectious Diseases Hospital, Sofia. Croatia: (J. Begovac), University Hospital of Infectious Diseases, Zagreb. Czech Republic: (L. Machala) and D. Jilich, Faculty Hospital Bulovka, Prague; and D. Sedlacek, Charles University Hospital, Plzen. Denmark: (J. Nielsen), G. Kronborg, T. Benfield and M. Larsen, Hvidovre Hospital, Copenhagen; J. Gerstoft, T. Katzenstein, A.-B. E. Hansen and P. Skinhøj, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen; C. Pedersen, Odense University Hospital, Odense; L. Ostergaard, Skejby Hospital, Aarhus; U. B. Dragsted, Roskilde Hospital, Roskilde; and L. N. Nielsen, Hillerod Hospital, Hillerod. Estonia: (K. Zilmer), West-Tallinn Central Hospital, Tallinn; and Jelena Smidt, Nakkusosakond Siseklinik, Kohtla-Järve. Finland: (M. Ristola), Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki. France: (C. Katlama), Hôpital de la Pitié-Salpétière, Paris; J. P. Viard, Hôtel-Dieu, Paris; P. M. Girard, Hospital Saint-Antoine, Paris; P. Vanhems, University Claude Bernard, Lyon; C. Pradier, Hôpital de l'Archet, Nice; F. Dabis and D. Neau, Unité INSERM, Bordeaux; and C. Duvivier, Hôpital Necker-Enfants Malades, Paris. Germany: (J. Rockstroh), Universitäts Klinik Bonn; R. Schmidt, Medizinische Hochschule, Hannover; J. van Lunzen and O. Degen, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hamburg; H. J. Stellbrink, IPM Study Center, Hamburg; M. Bickel, J. W. Goethe University Hospital, Frankfurt; J. Bogner, Medizinische Poliklinik, Munich; and G. Fätkenheuer, Universität Köln, Cologne. Greece: (J. Kosmidis), P. Gargalianos, G. Xylomenos and J. Perdios, Athens General Hospital; and H. Sambatakou, Ippokration General Hospital, Athens. Hungary: (D. Banhegyi), Szent Lásló Hospital, Budapest. Iceland: (M. Gottfredsson), Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik. Ireland: (F. Mulcahy), St James's Hospital, Dublin. Israel: (I. Yust), D. Turner and M. Burke, Ichilov Hospital, Tel Aviv; S. Pollack and G. Hassoun, Rambam Medical Center, Haifa; and H. Elinav and M. Haouzi, Hadassah University Hospital, Jerusalem. Italy: (A. D'Arminio Monforte), Istituto Di Clinica Malattie Infettive e Tropicale, Milan; R. Esposito, I. Mazeu and C. Mussini, Università Modena, Modena; C. Arici, Ospedale Riuniti, Bergamo; R. Pristera, Ospedale Generale Regionale, Bolzano; F. Mazzotta and A. Gabbuti, Ospedale S. Maria Annunziata, Firenze; V. Vullo and M. Lichtner, University di Roma la Sapienza, Rome; A. Chirianni, E. Montesarchio and M. Gargiulo, Presidio Ospedaliero A. D. Cotugno, Monaldi Hospital, Napoli; G. D′Offizi, C. Taibi and A. Antorini, Istituto Nazionale Malattie Infettive Lazzaro Spallanzani, Rome; A. Lazzarin, A. Castagna and N. Gianotti, Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan; and M. Galli and A. Ridolfo, Osp. L. Sacco, Milan. Latvia: (B. Rozentale) and I. Zeltina, Infectology Centre of Latvia, Riga. Lithuania: (S. Chaplinskas), Lithuanian AIDS Centre, Vilnius. Luxembourg: (T. Staub) and R. Hemmer, Centre Hospitalier, Luxembourg. The Netherlands: (P. Reiss), Academisch Medisch Centrum bij de Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam. Norway: (V. Ormaasen), A. Maeland and J. Bruun, Ullevål Hospital, Oslo. Poland: (B. Knysz) and J. Gasiorowski, Medical University, Wroclaw; A. Horban and E. Bakowska, Centrum Diagnostyki i Terapii AIDS, Warsaw; A. Grzeszczuk and R. Flisiak, Medical University, Bialystok; A. Boron-Kaczmarska, M. Pynka and M. Parczewski, Medical University, Szczecin; M. Beniowski and E. Mularska, Osrodek Diagnostyki i Terapii AIDS, Chorzow; H. Trocha, Medical University, Gdansk; and E. Jablonowska, E. Malolepsza and K. Wojcik, Wojewodzki Szpital Specjalistyczny, Lodz. Portugal: (M. Doroana) and L. Caldeira, Hospital Santa Maria, Lisbon; K. Mansinho, Hospital de Egas Moniz, Lisbon; and F. Maltez, Hospital Curry Cabral, Lisbon. Romania: (D. Duiculescu), Spitalul de Boli Infectioase si Tropicale—Dr Victor Babes, Bucarest. Russia: (A. Rakhmanova), Medical Academy Botkin Hospital, St Petersburg; A. Rakhmanova, St Petersburg AIDS Centre, St Petersburg; S. Buzunova, Novgorod Centre for AIDS, Novgorod; I. Khromova, Centre for HIV/AIDS & and Infectious Diseases, Kaliningrad; and E. Kuzovatova, Nizhny Novgorod Scientific and Research Institute, Nizhny Novogrod. Serbia: (D. Jevtovic), Institute for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Belgrade. Slovakia: (M. Mokráš) and D. Staneková, Dérer Hospital, Bratislava. Slovenia: (J. Tomazic), University Clinical Centre Ljubljana, Ljubljana. Spain: (J. González-Lahoz), V. Soriano and P. Labarga, Hospital Carlos III, Madrid; S. Moreno and J. M. Rodriguez, Hospital Ramon y Cajal, Madrid; B. Clotet, A. Jou, R. Paredes, C. Tural, J. Puig and I. Bravo, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona; J. M. Gatell and J. M. Miró, Hospital Clinic i Provincial, Barcelona; P. Domingo, M. Gutierrez, G. Mateo and M. A. Sambeat, Hospital Sant Pau, Barcelona; and J. Medrano, Hospital Universitario de Alava, Vitoria-Gasteiz. Sweden: (A. Blaxhult), Venhaelsan-Sodersjukhuset, Stockholm; L. Flamholc, Malmö University Hospital, Malmö; and A. Thalme and A. Sonnerborg, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm. Switzerland: (B. Ledergerber) and R. Weber, University Hospital, Zürich; P. Francioli and M. Cavassini, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne; B. Hirschel and E. Boffi, Hospital Cantonal Universitaire de Geneve, Geneve; H. Furrer, Inselspital Bern, Bern; M. Battegay and L. Elzi, University Hospital Basel; and P. Vernazza, Kantonsspital, St Gallen. Ukraine: (E. Kravchenko) and N. Chentsova, Kiev Centre for AIDS, Kiev; V. Frolov and G. Kutsyna, Luhansk State Medical University, Luhansk; S. Servitskiy, Odessa Region AIDS Center, Odessa; A. Kuznetsova, Kharkov State Medical University, Kharkov; and G. Kyselyova, Crimean Republican AIDS Centre, Simferopol. UK: (B. Gazzard), St Stephen's Clinic, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London; A. M. Johnson and E. Simons, Mortimer Market Centre, London; A. Phillips, M. A. Johnson and A. Mocroft, Royal Free and University College Medical School, London (Royal Free Campus); C. Orkin, Royal London Hospital, London; J. Weber and G. Scullard, Imperial College School of Medicine at St Mary's, London; M. Fisher, Royal Sussex County Hospital, Brighton; and C. Leen, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh. Steering Committee: J. Gatell, B. Gazzard, A. Horban, I. Karpov, B. Ledergerber, M. Losso, A. D'Arminio Monforte, C. Pedersen, A. Rakhmanova, M. Ristola, J. Rockstroh (Chair) and S. De Wit (Vice-Chair). Additional voting members: J. Lundgren, A. Phillips and P. Reiss. Coordinating centre staff: O. Kirk, D. Podlekareva, J. Kjær, L. Peters, J. E. Nielsen, C. Matthews, A. H. Fischer, A. Bojesen and D. Raben. Statistical staff: A. Mocroft, A. Phillips, A. Cozzi-Lepri, D. Grint, L. Shepherd and A. Schultze. EuroSIDA representatives to EuroCoord: O. Kirk, A. Mocroft, J. Grarup, P. Reiss, A. Cozzi-Lepri, R. Thiebaut, J. Rockstroh, D. Burger, R. Paredes, J. Kjær and L. Peters.

ICONA Foundation Study Group

Board of Directors: M. Moroni (Chair), M. Andreoni, G. Angarano, A. Antinori, A. D'Arminio Monforte, F. Castelli, R. Cauda, G. Di Perri, M. Galli, R. Iardino, G. Ippolito, A. Lazzarin, C. F. Perno, F. von Schloesser and P. Viale. Scientific secretary: A. D'Arminio Monforte, A. Antinori, A. Castagna, F. Ceccherini-Silberstein, A. Cozzi-Lepri, E. Girardi, S. Lo Caputo, C. Mussini and M. Puoti. Steering Committee: M. Andreoni, A. Ammassari, A. Antinori, A. D'Arminio Monforte, C. Balotta, P. Bonfanti, S. Bonora, M. Borderi, M. R. Capobianchi, A. Castagna, F. Ceccherini-Silberstein, A. Cingolani, P. Cinque, A. Cozzi-Lepri, A. D'Arminio Monforte, A. De Luca, A. Di Biagio, E. Girardi, N. Gianotti, A. Gori, G. Guaraldi, G. Lapadula, M. Lichtner, S. Lo Caputo, G. Madeddu, F. Maggiolo, G. Marchetti, S. Marcotullio, L. Monno, C. Mussini, M. Puoti, E. Quiros Roldan and S. Rusconi. Statistical and monitoring team: A. Cozzi-Lepri, P. Cicconi, I. Fanti, T. Formenti, L. Galli and P. Lorenzini. Biological bank: F. Carletti, S. Carrara, A. Castrogiovanni, A. Di Caro, F. Petrone, G. Prota and S. Quartu. Participating physicians and centres: Italy: A. Giacometti, A. Costantini and S. Mazzoccato (Ancona); G. Angarano, L. Monno and C. Santoro (Bari); F. Maggiolo and C. Suardi (Bergamo); P. Viale, E. Vanino and G. Verucchi (Bologna); F. Castelli, E. Quiros Roldan and C. Minardi (Brescia); T. Quirino and C. Abeli (Busto Arsizio); P. E. Manconi and P. Piano (Cagliari); J. Vecchiet and K. Falasca (Chieti); L. Sighinolfi and D. Segala (Ferrara); F. Mazzotta and S. Lo Caputo (Firenze); G. Cassola, C. Viscoli, A. Alessandrini, R. Piscopo and G. Mazzarello (Genova); C. Mastroianni and V. Belvisi (Latina); P. Bonfanti and I. Caramma (Lecco); A. Chiodera and A. P. Castelli (Macerata); M. Galli, A. Lazzarin, G. Rizzardini, M. Puoti, A. D'Arminio Monforte, A. L. Ridolfo, R. Piolini, A. Castagna, S. Salpietro, L. Carenzi, M. C. Moioli, C. Tincati and G. Marchetti (Milano); C. Mussini and C. Puzzolante (Modena); A. Gori and G. Lapadula (Monza); N. Abrescia, A. Chirianni, M. G. Guida and M. Gargiulo (Napoli); F. Baldelli and D. Francisci (Perugia); G. Parruti and T. Ursini (Pescara); G. Magnani and M. A. Ursitti (Reggio Emilia); R. Cauda, M. Andreoni, A. Antinori, V. Vullo, A. Cingolani, A. d'Avino, L. Gallo, E. Nicastri, R. Acinapura, M. Capozzi, R. Libertone and G. Tebano (Roma); A. Cattelan and L. Sasset (Rovigo); M. S. Mura and G. Madeddu (Sassari); A. De Luca and B. Rossetti (Siena); P. Caramello, G. Di Perri, G. C. Orofino, S. Bonora and M. Sciandra (Torino); M. Bassetti and A. Londero (Udine); and G. Pellizzer and V. Manfrin (Vicenza).

Kompetenznetz HIV/AIDS (KompNet HIV/AIDS)

N. H. Brockmeyer (Speaker) and A. Skaletz-Rorowski (Scientific Coordinator), Klinik für Dermatologie, Venerologie und Allergologie, Ruhr-Universität, Bochum; S. Dupke, A. Baumgarten and A. Carganico, Gemeinschaftspraxis Driesener Straße, Berlin; S. Köppe and P. Kreckel, Gemeinschaftspraxis Mehringdamm, Berlin; E. Lauenroth-Mai, Gemeinschaftspraxis Turmstraße, Berlin; M. Freiwald-Rausch, Gemeinschaftspraxis Fuggerstraße, Berlin; J. Gölz and A. Moll, Praxiszentrum Kaiserdamm, Berlin; M. Zeitz, Universitätsklinikum Benjamin Franklin, Charité, Berlin; M. Hower, Universitätsklinikum Dortmund; S. Reuter, B. Jensen, Universitätsklinikum Düsseldorf; T. Harrer, Medizinische Klinik 3, Universitätsklinikum, Erlangen; S. Esser, Klinik für Dermatologie, Universitätsklinikum Essen; H. R. Brodt, HIV Center, Universitätsklinikum, Frankfurt; A. Plettenberg and A. Stöhr, Ifi-Institut, Hamburg; T. Buhk and H. J. Stellbrink, ICH Grindelpraxis, Infektionsepidemiologisches Centrum, Hamburg; M. Stoll and R. Schmidt, Medizinische Hochschule, Hannover; B. Kuhlmann, Praxis Georgstraße, Hannover; F. A. Mosthaf, Gemeinschaftspraxis, Kriegsstraße, Karlsruhe; A. Rieke, Städtisches Krankenhaus Kemperhof, Koblenz; S. Scholten, Praxis Hohenstaufenring, Köln; W. Becker and R. Volkert, Gemeinschaftspraxis Isartorplatz, München; H. Jäger, MVZ Karlsplatz, HIV Research and Clinical Centre, München; H. Hartl, Praxisgemeinschaft Franz Joseph-Straße, München; A. Mutz, Klinikum Osnabrück; and A. Ulmer and M. Müller, Gemeinschaftspraxis, Stuttgart.

Royal Free Hospital

Prof. Margaret Johnson, Clinical Director, HIV Services, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust.

Members of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study

V. Aubert, J. Barth, M. Battegay, E. Bernasconi, J. Böni, H. C. Bucher, C. Burton-Jeangros, A. Calmy, M. Cavassini, M. Egger, L. Elzi, J. Fehr, J. Fellay, H. Furrer (Chairman of the Clinical and Laboratory Committee), C. A. Fux, M. Gorgievski, H. Günthard (President of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study), D. Haerry (Deputy of ‘Positive Council’), B. Hasse, H. H. Hirsch, I. Hösli, C. Kahlert, L. Kaiser, O. Keiser, T. Klimkait, H. Kovari, R. Kouyos, B. Ledergerber, G. Martinetti, B. Martinez de Tejada, K. Metzner, N. Müller, D. Nadal, G. Pantaleo, A. Rauch (Chairman of the Scientific Board), S. Regenass, M. Rickenbach (Head of Data Center), C. Rudin (Chairman of the Mother & Child Substudy), P. Schmid, D. Schultze, F. Schöni-Affolter, J. Schüpbach, R. Speck, C. Staehelin, P. Tarr, A. Telenti, A. Trkola, P. Vernazza, R. Weber and S. Yerly.

Funding

This study was supported by ‘CHAIN, Collaborative HIV and Anti-HIV Drug Resistance Network’, Integrated Project no. 223131, European Commission Framework 7 Program, Gilead Sciences and Roche Diagnostics GmBH. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF grant #33CS30-134277, −148522 and #108787) and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study research foundation. Primary support for EuroSIDA is provided by the European Commission BIOMED 1 (CT94-1637) and BIOMED 2 (CT97-2713) and the 5th Framework (QLK2-2000-00773), the 6th Framework (LSHP-CT-2006-018632) and the 7th Framework (FP7/2007-2013, EuroCoord no. 260694) programmes. Current support also includes unrestricted grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen R&D, Merck and Co. Inc., Pfizer Inc. and GlaxoSmithKline LLC.

All funding organizations had no influence at all on the study design, the experimental procedures, the analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Transparency declarations

A. C.-L. declares no conflict of interest although he received consulting fees from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences and Roche for other projects. M. D. has received travel grants from Abbott and Merck Sharp & Dohme, has received a research grant from Merck Sharp & Dohme and has been an adviser for Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Gilead Sciences and Janssen-Cilag. F. C.-S. has received funds for research grants, attending symposia, speaking and organizing educational activities from Abbott, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Gilead, Janssen, ViiV Healthcare, Roche, Virco and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A. D. M. has received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbvie, ViiV, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Janssen and Gilead. E. C. has received travel grants, honoraria and grants for other projects from Gilead Sciences, Janssen-Cilag and Merck Sharp & Dohme. H. F. declares no conflict of interest although the institution of H. F. has received payments for participation in advisory boards and/or unrestricted educational or scientific grants and/or travel grants from Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, ViiV Healthcare, Roche, Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim and Tibotec-Janssen. H. F. G. has been an adviser and/or consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott, Gilead, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Tibotec, Pfizer and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and has received unrestricted research and educational grants from Roche, Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Merck Sharp & Dohme (all money went to institution). R. P. has received consulting fees from Pfizer, ViiV Healthcare, Merck Sharpe & Dohme and Bristol Myers-Squibb, and grant support from Pfizer, ViiV Healthcare, Roche Diagnostics, Siemens, Merck Sharpe & Dohme and Boehringer Ingelheim. K. J. M. has received travel grants and honoraria from Gilead Sciences, Roche Diagnostics, Tibotec, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Abbott; the University of Zurich has received research grants from Gilead Sciences, Roche Diagnostics and Merck Sharp & Dohme for studies that K. J. M. serves as principal investigator and advisory board honoraria from Gilead Sciences. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the International Workshop on HIV & Hepatitis Virus Drug Resistance and Curative Strategies, Toronto, Canada, 2013 [Antiviral Therapy 2013; 18 Suppl 1: A41 (Abstract 33)].

We are grateful to patients contributing their data and plasma samples for this study and their treating physicians and all the cohorts for data management and biobanking.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Bernard Masquelier, who died in March 2013.

References

- 1.Johnson VA, Calvez V, Gunthard HF, et al. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: March 2013. Top Antivir Med. 2013;21:6–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. HIV Drug Resistance Report 2012. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/drugresistance/report2012/en/

- 3.Halvas EK, Aldrovandi GM, Balfe P, et al. Blinded, multicenter comparison of methods to detect a drug-resistant mutant of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 at low frequency. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2612–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00449-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuurman R, Demeter L, Reichelderfer P, et al. Worldwide evaluation of DNA sequencing approaches for identification of drug resistance mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2291–6. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2291-2296.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilks CF, Crowley S, Ekpini R, et al. The WHO public-health approach to antiretroviral treatment against HIV in resource-limited settings. Lancet. 2006;368:505–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Hoy JF, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2012 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2012;308:387–402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. 2012. Technical Update on Treatment Optimization. Use of Efavirenz during Pregnancy: A Public Health Perspectivehttp://www.who.int/hiv/pub/treatment2/efavirenz/en/

- 8.DHHS. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. 2013;5:79–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castro H, Pillay D, Cane P, et al. Persistence of HIV-1 transmitted drug resistance mutations. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1459–63. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snedecor SJ, Khachatryan A, Nedrow K, et al. The prevalence of transmitted resistance to first-generation non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and its potential economic impact in HIV-infected patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittkop L, Gunthard HF, de Wolf F, et al. Effect of transmitted drug resistance on virological and immunological response to initial combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV (EuroCoord-CHAIN joint project): a European multicohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:363–71. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domingo E, Escarmis C, Sevilla N, et al. Basic concepts in RNA virus evolution. FASEB J. 1996;10:859–64. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.8.8666162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gadhamsetty S, Dixit NM. Estimating frequencies of minority nevirapine-resistant strains in chronically HIV-1-infected individuals naive to nevirapine by using stochastic simulations and a mathematical model. J Virol. 2010;84:10230–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01010-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzner KJ, Scherrer AU, Preiswerk B, et al. Origin of minority drug-resistant HIV-1 variants in primary HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1102–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li JZ, Paredes R, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Low-frequency HIV-1 drug resistance mutations and risk of NNRTI-based antiretroviral treatment failure: a systematic review and pooled analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:1327–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandenbroucke JP, Pearce N. Case–control studies: basic concepts. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1480–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metzner KJ, Giulieri SG, Knoepfel SA, et al. Minority quasispecies of drug-resistant HIV-1 that lead to early therapy failure in treatment-naive and -adherent patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:239–47. doi: 10.1086/595703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varghese V, Shahriar R, Rhee SY, et al. Minority variants associated with transmitted and acquired HIV-1 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance: implications for the use of second-generation nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:309–15. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bca669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paredes R, Lalama CM, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Pre-existing minority drug-resistant HIV-1 variants, adherence, and risk of antiretroviral treatment failure. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:662–71. doi: 10.1086/650543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li JZ, Paredes R, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Relationship between minority nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance mutations, adherence, and the risk of virologic failure. AIDS. 2012;26:185–92. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834e9d7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li JZ, Paredes R, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Impact of minority nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance mutations on resistance genotype after virologic failure. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:893–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buckheit RW, Jr, Fliakas-Boltz V, Decker WD, et al. Comparative anti-HIV evaluation of diverse HIV-1-specific reverse transcriptase inhibitor-resistant virus isolates demonstrates the existence of distinct phenotypic subgroups. Antiviral Res. 1995;26:117–32. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(94)00069-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackie NE, Dunn DT, Dolling D, et al. The impact of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase polymorphisms on responses to first-line nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based therapy in HIV-1-infected adults. AIDS. 2013;27:2245–53. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283636179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacheler L, Jeffrey S, Hanna G, et al. Genotypic correlates of phenotypic resistance to efavirenz in virus isolates from patients failing nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapy. J Virol. 2001;75:4999–5008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.4999-5008.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paredes R, Marconi VC, Campbell TB, et al. Systematic evaluation of allele-specific real-time PCR for the detection of minor HIV-1 variants with pol and env resistance mutations. J Virol Methods. 2007;146:136–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Giallonardo F, Zagordi O, Duport Y, et al. Next-generation sequencing of HIV-1 RNA genomes: determination of error rates and minimizing artificial recombination. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fourati S, Malet I, Lambert S, et al. E138K and M184I mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase coemerge as a result of APOBEC3 editing in the absence of drug exposure. AIDS. 2012;26:1619–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283560703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim EY, Bhattacharya T, Kunstman K, et al. Human APOBEC3G-mediated editing can promote HIV-1 sequence diversification and accelerate adaptation to selective pressure. J Virol. 2010;84:10402–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01223-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schackman BR, Ribaudo HJ, Krambrink A, et al. Racial differences in virologic failure associated with adherence and quality of life on efavirenz-containing regimens for initial HIV therapy: results of ACTG A5095. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:547–54. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e31815ac499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frasco MA, Mack WJ, Van Den Berg D, et al. Underlying genetic structure impacts the association between CYP2B6 polymorphisms and response to efavirenz and nevirapine. AIDS. 2012;26:2097–106. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283593602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribaudo HJ, Liu HA, Schwab M, et al. Effect of CYP2B6, ABCB1, and CYP3A5 polymorphisms on efavirenz pharmacokinetics and treatment response: an AIDS Clinical Trials Group study. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:717–22. doi: 10.1086/655470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.