Abstract

Objectives

Constitutive overexpression of patAB has been observed in several unrelated fluoroquinolone-resistant laboratory mutants and clinical isolates; therefore, we sought to identify the cause of this overexpression.

Methods

Constitutive patAB overexpression in two clinical isolates and a laboratory-selected mutant was investigated using a whole-genome transformation approach. To determine the effect of the detected terminator mutations, the WT and mutated patA leader sequences were cloned upstream of a GFP reporter. Finally, mutation of the opposing base in the stem–loop structure was carried out.

Results

We identified three novel mutations causing up-regulation of patAB. All three of these were located in the upstream region of patA and affected the same Rho-independent transcriptional terminator structure. Each mutation was predicted to destabilize the terminator stem–loop to a different degree, and there was a strong correlation between predicted terminator stability and patAB expression level. Using a GFP reporter of patA transcription, these terminator mutations led to increased transcription of a downstream gene. For one mutant sequence, terminator stability could be restored by mutation of the opposing base in the stem–loop structure, demonstrating that transcriptional suppression of patAB is mediated by the terminator stem–loop structure.

Conclusions

This study showed that a mutation in a Rho-independent transcriptional terminator structure confers overexpression of patAB and fluoroquinolone resistance. Understanding how levels of the PatAB efflux pump are regulated increases our knowledge of pneumococcal biology and how the pneumococcus can respond to various stresses, including antimicrobials.

Keywords: multidrug resistance, efflux, antimicrobial resistance mechanisms, regulation

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is an important human pathogen representing a major disease burden worldwide. It is the main bacterial cause of community-acquired pneumonia, as well as being the cause of severe invasive infections such as meningitis. Fluoroquinolones are one of the classes of antibiotics frequently used to treat pneumococcal disease.1 However, fluoroquinolone resistance in pneumococci is easily selected and causes treatment failures.2 Known mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in pneumococci are target site mutations in topoisomerase genes3,4 and the overexpression of the ABC transporter genes patA and patB.5–7 PatA and PatB dimerize to form a functional ABC transporter that exports certain hydrophilic fluoroquinolones, as well as other toxic compounds, such as the dye ethidium bromide.8

As well as drug efflux, PatAB has also been implicated in relieving a fitness cost associated with linezolid resistance mutations9 and intolerance of pH stress.10 Up-regulation of patAB has also been observed as the defining characteristic of a meningitis isolate compared with a bloodstream isolate taken from the same patient.11 These observations hint at a more fundamental role for the patAB transporter in pneumococcal stress responses. Elucidating the regulatory mechanisms controlling patAB may provide further insight into the role of this transporter in the pneumococcal cell. Specific regulators controlling expression of patAB are unknown, but two previous studies have suggested that expression of these genes is induced by exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of fluoroquinolones and by DNA damage.12,13

In two independent studies, constitutive overexpression of patAB was associated with a G–T mutation 46 bp upstream of patA.9–11 This is predicted to affect folding of a Rho-independent transcriptional terminator, and hypothesized to allow increased transcriptional read-through into patA.11 In this study, we identified three novel mutations affecting this putative terminator structure in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae with constitutive overexpression of patAB. We investigated the effect of these mutations on patA transcription using GFP reporter fusions, and showed that transcriptional repression of GFP could be restored by reconstituting the terminator base-pairing structure. This study shows that attenuator mutations mediate clinically relevant overexpression of patA(B) and fluoroquinolone resistance.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth

All S. pneumoniae strains and clinical isolates (Table 1) were grown statically at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in brain heart infusion broth (BHI; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) or on Columbia agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) supplemented with 5% defibrinated horse blood (TCS Biosciences, Buckingham, UK). Bacterial growth in broth was assessed by measurement of OD at 660 nm (OD660) of liquid cultures. Escherichia coli strains used for plasmid construction were grown overnight on LB (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) agar at 37°C or in LB broth at 37°C with shaking at 180 rpm.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| R6 | unencapsulated WT strain, ATCC BAA255 | 27 |

| M168 | reserpine-resistant mutant derived from M4 | 7 |

| M184 | reserpine-resistant mutant derived from R6 | 7 |

| M87 | clinical isolate from MRL Pharmaceutical Services | 28 |

| M101 | clinical isolate from MRL Pharmaceutical Services | 28 |

| M505 | R6 recipient transformed with M101 DNA, selected on 8 mg/L ethidium bromide | this study |

| M506 | R6 recipient transformed with M187 DNA, selected on 8 mg/L ethidium bromide | this study |

| M507 | R6 recipient transformed with M174 DNA, selected on 8 mg/L ethidium bromide | this study |

| M511 | R6 containing pBAV1K-gfp82 vector | this study |

| M512 | R6 containing construct pBAV1K-gfp82-WT | this study |

| M513 | R6 containing construct pBAV1K-gfp82-v101 | this study |

| M514 | R6 containing construct pBAV1K-gfp82-v101c | this study |

| M517 | R6 containing construct pBAV1K-gfp82-v168 | this study |

| M518 | R6 containing construct pBAV1K-gfp82-v168c | this study |

| M515 | R6 containing construct pBAV1K-gfp82-v87 | this study |

| M516 | R6 containing construct pBAV1K-gfp82-v87c | this study |

DNA extraction and PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from all strains using the Wizard Genomic DNA extraction kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. The primer sequences and PCR conditions used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers and DNA oligonucleotide used in this study

| Target | Forward primer | Reverse primer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer pair | |||

| 1 | patA | TCTTGCTCAGTCCATCATCGAA-TATA | CCGCTGTGGATTAGTTCATTTCC |

| 2 | patB | AGAATCCAGTCCAGCGAAAGCT | GAAAGAACGACCAGATGTTCCAAT |

| 3 | patA first half | TCTTGCTCAGTCCATCATCGAA-TATA | CAGCATCGGTTCCTTGTC |

| 4 | patA second half | CAGATGAAGAGTTGGTTGGA | CCGCTGTGGATTAGTTCATTTCC |

| 5 | patA promoter | GATAGGGCAGAAGAGCATCC | GATAACGCGGTTGCAGAAGT |

| 6 | patA qRT–PCR | TCTTAGGCGCCCTCCTTACT | ATAGGCTGCGAGGACAAC |

| 7 | patB qRT–PCR | AGAAATGTGACGCTGGCTCT | TTCTGCTGGAGGTTGGTGT |

| 8 | guaA qRT–PCR | GCGCTTCGTCAGAATAAACC | AGTCCTTGCCAGTGACCTTC |

| 9 | spr1886 qRT–PCR | GGATTGGGAATCGTTTAGGG | AGAATCCAGTCCAGCGAAAG |

| 10 | hexA qRT–PCR | TGTCTAGTGTGCCACGGATT | CGCTGCGCTAATCAAACTCT |

| 11 | PBAV1K-gfp82 cloning site | TAGTATCGACGGAGCCGATT | TGTGCCCATTAACATCACCA |

| DNA oligonucleotide | |||

| WT patA upstream region | taagaattcaaccaagactcactagttaatctagctgtatcaaggagacttctttgacaattctccacttttttgcta gaataacatcacacaaacagaatgaaaaggagctgacgcattgtcgctcccttttgtctattttttctagaaag | ||

Bold and underlined text represents restriction enzyme cleavage sites.

Transformation

Transformation of S. pneumoniae R6 was carried out as described previously.7 Briefly, mid-logarithmic phase cultures of R6 were diluted 1 : 20 in competence medium [Todd–Hewitt broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) containing 1 mM calcium chloride (Sigma Aldrich Ltd, Dorset, UK), 0.2% BSA (Sigma Aldrich Ltd, Dorset, UK) and 100 ng/mL competence-stimulating peptide 1 (CSP1; Mimotopes, Clayton, Victoria, Australia)]. For whole-genome transformation, genomic DNA from the donor strain was added to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/L to aliquots of the competent cell suspension. For transformation with PCR amplimers, 20 μL of purified PCR amplimer was added to 500 μL of cell suspension. Transformation reactions were incubated for 3 h at 37°C, then 20 and 200 volumes were spread onto agar plates containing 8 mg/L ethidium bromide. Viable counts were determined in parallel to allow estimation of the transformation frequency.

Illumina sequencing and data analysis

Illumina whole-genome sequencing was carried out by Genepool (Edinburgh, UK) according to standard protocols to give 100 bp paired-end reads. Reads were mapped against the published R6 genome sequence (GenBank accession number NC_003098) using Bowtie214 using the –very-sensitive-local setting, and a consensus pileup was generated using mpileup in Samtools (version 0.1.18).15 Sets of putative SNPs and small indels were generated using BCFtools (version 0.1.17-dev).15

Susceptibility of S. pneumoniae to antibiotics and dyes

The MICs of ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and ethidium bromide were determined using the standardized agar doubling dilution method according to the BSAC.16

Ethidium bromide accumulation

Intracellular accumulation of ethidium bromide was measured by monitoring fluorescence over time, as follows. Logarithmic-phase bacterial cultures were pelleted by centrifugation at 2200 g and resuspended in PBS (Life Technologies, cat. no. 14040-133; 2160 mg/L Na2HPO4, 8000 mg/L NaCl, 200 mg/L KH2PO4, 200 mg/L KCl, 100 mg/L MgCl2 and 100 mg/L CaCl2). Cell suspensions were adjusted to an OD660 of 0.1 with fresh PBS, and a 100-cell suspension was added in triplicate to a black microtitre tray. Fluorescence was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 530 and 600 nm, respectively, using a FLUOstar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtech, Aylesbury, UK) every 2 min for a total of 30 min. A final concentration of 100 μM ethidium bromide was added to each well by injection on the second cycle of measurement.

qRT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted from three biological replicates of logarithmic-phase cultures of each test strain using a Promega SV Total RNA Isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Southampton, UK). RNA and contaminating DNA concentrations were measured using a Qubit fluorimeter according to the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). Residual DNA contamination was removed by treatment with Turbo DNase (Life Technologies), and cDNA was generated using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) following the first-strand synthesis protocol supplied by the manufacturer. Expression of patA, patB, spr1886 and guaA was measured relative to expression of rpoB by SYBR Green Quantitative real-time (qRT) PCR. Reactions consisted of 12.5 μL IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, UK), 375 nM each of forward and reverse primers and 1 μL cDNA in a 25 µL reaction. Real-time PCR was carried out using a Bio-Rad CFX96 thermal cycler with the following protocol: 3 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 54.5°C. Expression values were calculated using the Pfaffl method.17

patA expression reporter plasmid construction and GFP assay

To generate plasmid pBAV1K-gfp82, plasmids pBAV1K-T5-gfp18 and pMW8219 were digested with EcoRI and PstI (Thermo Scientific) and digestion products separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The 2800 bp plasmid backbone of pBAVK1K-T5-gfp and the 824 bp band corresponding to the gfp gene of pMW82 were extracted using a Qiagen gel extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA fragments were ligated using QuickStick ligase (Bioline) and used to transform E. coli Top10 cells (Life Technologies). Transformants were selected on 50 mg/L kanamycin. To remove DNA methylation for subsequent digestions, extracted plasmids were transformed into E. coli JM110 cells and re-purified.

To clone the patA promoter into pBAV1K-gfp82, giving pBAV1K-gfp82-WT, a 144 bp DNA fragment was synthesized by GeneArt (Life Technologies) that covered the region from 12 to 146 bp upstream of the patA start codon and incorporated a 5′ EcoRI site and a 3′ XbaI site. The promoter fragment was digested with EcoRI and XbaI, purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and combined in a 100 : 1 ratio with pBAV1K2 DNA linearized with XbaI and EcoRI. The DNA fragments were ligated with QuickStick ligase and used to transform E. coli Top10 cells. Transformants were selected on 50 mg/L kanamycin and screened for successful incorporation of the insert by PCR with primer pair 11.

Plasmid DNA was extracted from E. coli cells using a QIAquick Miniprep Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions, and 20 μL of each plasmid preparation was used to transform S. pneumoniae R6 as described above. Successful transformants were selected on plates containing 100 mg/L kanamycin.

To measure expression of patA from the reporter construct, stationary-phase cultures of R6 containing pBAV1K-gfp82 constructs were diluted to an OD600 of 0.01 in BHI broth, and 200 μL of diluted culture was added in duplicate to a black microtitre tray with a clear base (Corning). Cultures were incubated in a Fluostar Optima at 37°C for 12 h, and simultaneous fluorescence (excitation wavelength 492 nm, emission wavelength 520 nm) and absorbance (600 nm) measurements were taken every 3 min. Absorbance and fluorescence values at each timepoint were calculated as the average of three biological replicates.

RNA structure prediction

Free energies of folding of RNA structures were predicted computationally using the RNAfold program from the Vienna RNA suite.20

Results

Genetic determinants causing fluoroquinolone resistance and patAB up-regulation could be transferred into an antibiotic-susceptible strain by a single round of transformation

Laboratory mutants and clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae that constitutively overexpress patAB have been described previously,7,9,11,12,21 but the mechanism has not been identified. Two recent whole-genome sequencing publications described a G–T mutation 46 bp upstream of patA associated with fluoroquinolone resistance.9,11 In this study, we investigated the cause of constitutive patAB overexpression in two further fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates and a laboratory mutant. The two clinical isolates, M101 and M87, were chosen from a set of previously described clinical isolates with elevated patAB expression.21,22 The third strain investigated was M168, a laboratory-selected mutant of type strain NCTC7465, selected for resistance to the efflux inhibitor reserpine.7

In the case of the laboratory-selected mutants, mutations causing the desired phenotype could be identified by a whole-genome re-sequencing approach: sequencing of the mutant and detection of polymorphisms with respect to the genome sequence of an isogenic parental strain. However, for the two clinical isolates investigated in this study, antibiotic-susceptible parental strains were not available for comparison so this approach could not be used. However, viable transformants could be selected on ethidium bromide (8 mg/L), a known PatAB substrate, when the unencapsulated laboratory strain R6 was transformed with high-molecular weight DNA extracted from either M101 or M87 (giving R6M101 and R6M87, respectively). Although a parental strain was available for the laboratory-selected strain M168, the same approach of whole-genome transformation into R6 (giving R6M168) was followed for consistency.

In all three cases, a single round of transformation was sufficient to select transformants with an ethidium bromide MIC of 32 or 64 mg/L, three to four dilutions higher than that of R6. The ethidium bromide MICs were slightly higher than those for the donor strains, possibly reflecting the expression of patAB in a different genetic background.

To confirm that the selection for ethidium bromide resistance correlated with the transfer of mutations causing patAB overexpression, we carried out three checks. Firstly, antibiotic susceptibility profiles were determined by agar doubling dilution MIC (Table 3). All three transformants were less susceptible to ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and ethidium bromide compared with R6, and this was reversed in the presence of sodium orthovanadate, an inhibitor of ABC transporters. The susceptibility of R6 to all three agents was also increased slightly in the presence of sodium orthovanadate, most likely due to inhibition of basal levels of the PatAB expressed by the R6 strain. Secondly, the intracellular accumulation of ethidium bromide was measured by fluorescence assay. Transformants showed a 20%–30% reduction in accumulation of ethidium bromide compared with R6 (Figure 1a). A previously described strain, M184,7 which expresses patAB at a very high level (>100-fold higher than R6, data not shown) was used as a positive control.

Table 3.

MICs of PatAB substrates for transformants R6M168, R6M101 and R6M87

| Strain | MIC (mg/L) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | CIP + Ort | NOR | NOR + Ort | EtBr | EtBr + Ort | |

| R6 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | <1 |

| M184 | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | 2 | 64 | <1 |

| R6M168 | 2 | 0.5 | 16 | 2 | 32 | <1 |

| R6M101 | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | 2 | 64 | <1 |

| R6M87 | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | 2 | 64 | <1 |

CIP, ciprofloxacin; NOR, norfloxacin; EtBr, ethidium bromide; Ort, 50 μM sodium orthovanadate.

Bold numbers indicate MIC values that are two or more dilutions higher than those for R6.

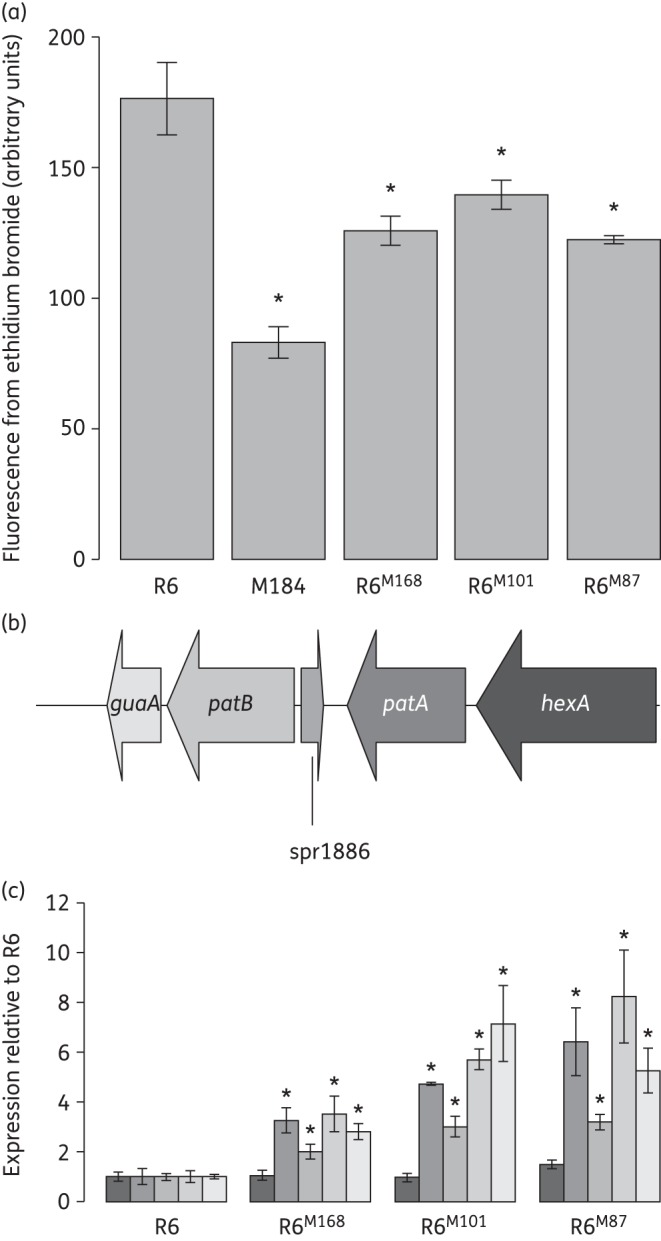

Figure 1.

Confirmation of patAB overexpression phenotype in transformants R6M168, R6M101 and R6M87. (a) Fluorescence due to intracellular accumulation of ethidium bromide following 10 min of incubation with 100 μM ethidium bromide. Bars and error bars represent averages and standard deviations of three biological replicates. *Accumulation significantly lower than R6; P < 0.05, one-tailed Student's t-test. A previously described strain, M184, was used as a positive control. (b) Representation of the patAB genetic locus. (c) Expression of patA, patB and neighbouring genes in R6 and transformants R6M168, R6M101 and R6M87 measured by qRT–PCR compared with rpoB. Bars represent average expressions relative to R6 from three biological replicates and are shaded by gene as in panel (b). Error bars represent standard deviations of three biological replicates. *Expression significantly different from R6; P < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test.

Finally, expression of patA and patB was measured directly by qRT–PCR. Expression of both patA and patB was significantly higher in R6M168, R6M101 and R6M87 than in R6 (Figure 1b and c and Table 4; P < 0.05). Taken together, these results made us confident that mutations causing patAB overexpression had been successfully transferred using the whole-genome transformation approach.

Table 4.

Expression of patA and patB in transformants R6M168, R6M101 and R6M87 compared with R6

| Fold change in expression compared with R6 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

patA |

patB |

|||

| average | SD | average | SD | |

| R6M168 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.7 |

| R6M101 | 4.7 | 0.1 | 5.7 | 0.4 |

| R6M87 | 6.4 | 1.4 | 8.2 | 1.9 |

SD, standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Sequencing of transformants revealed mutations in a Rho-independent terminator upstream of patA

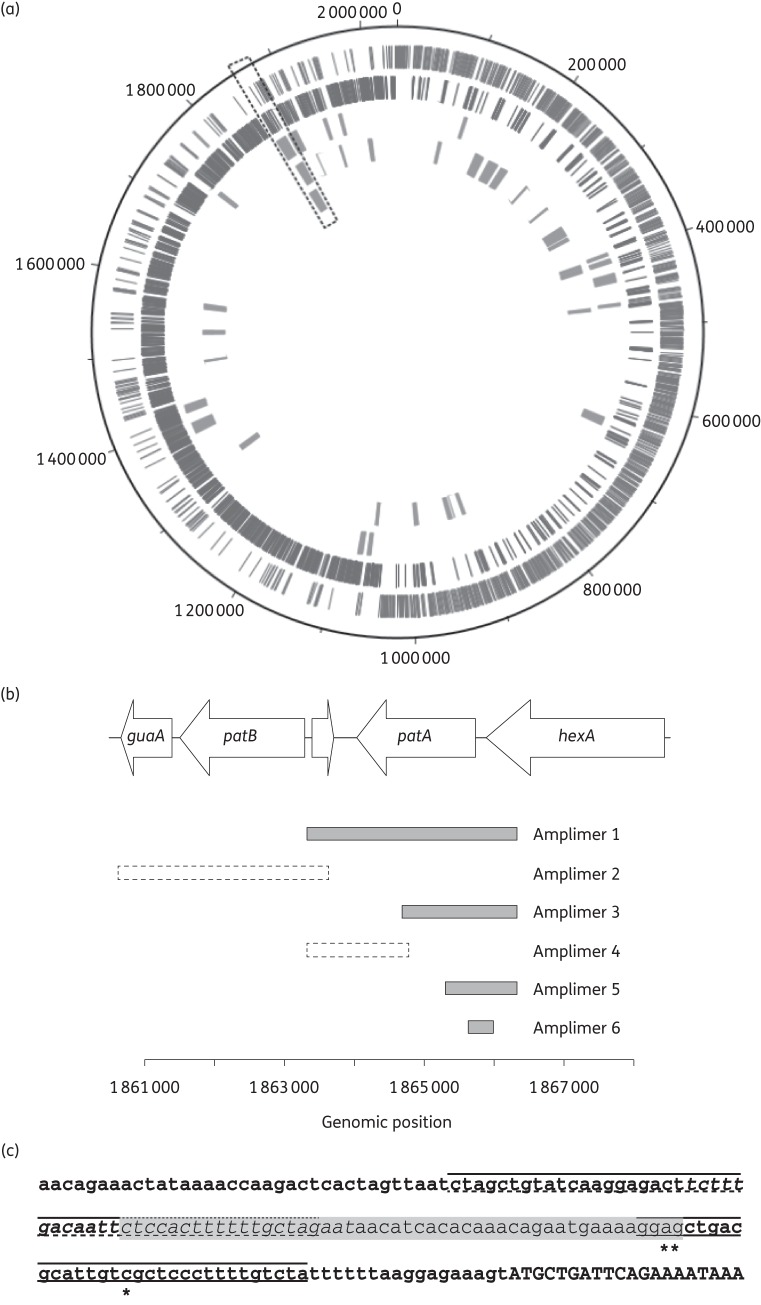

To identify mutations causing patAB overexpression in the three transformants, whole genomic DNA was extracted from strains R6, R6M168, R6M101 and R6M74 and sequenced using Illumina technology. Reads were aligned to the published R6 genome sequence (NC_003098) and SNPs detected. The laboratory stock of R6 used for our experiments differed from the published R6 genome sequence by 58 mutations (data not shown). These mutations were also observed in the three transformants and were discarded from further analysis. Regions of the transformant genomes where recombination had occurred between the donor and recipient genomes could be identified as clusters of SNPs relative to R6. Clusters were loosely defined as regions of the genome where the number of SNPs in a 5 kb sliding window was consistently greater than two. A single recombination event was observed in R6M168, occurring in the region of the genome that contains patAB. Multiple recombination events were observed in R6M101 and R6M87 (14 and 24, respectively). In both of these strains, however, there was a recombinant region in the vicinity of the patA and patB genes, as observed in R6M168 (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Locations of putative recombinant regions in transformants identified by whole-genome sequencing. (a) Recombinations mapped onto the R6 genome. Rings are numbered from outside to inside. Rings 1 and 2 represent R6 coding sequences encoded on the plus and minus strand, respectively. Rings 3, 4 and 5 represent putative recombinant regions in R6M101, R6M87 and R6M168, respectively. The region containing the patA and patB genes is indicated by the dashed box. (b) Extents of PCR amplimers from R6M101, R6M87 and R6M168 used for targeted transformation of R6 cells to determine the location of mutations causing patAB overexpression. Solid, filled boxes represent amplimers that produced ethidium bromide-resistant transformants. Dashed boxes represent amplimers for which no ethidium bromide-resistant transformants were obtained. (c) DNA sequence upstream of patA, with locations of mutations identified in R6M101, R6M87 and R6M168 indicated (*). The transcriptional attenuator predicted by Ribex, consisting of terminator (solid lines), anti-terminator (shaded text) and anti-anti-terminator (dashed lines) loops, is also indicated. The start of the patA coding sequence is shown in capital letters.

The recombinant regions that encompassed the patAB genes were examined in more detail. The minimum sizes of the recombinant regions (naively defined as the distance between the first and last SNP in the cluster) ranged between 9.7 and 12.2 kb. The clusters consisted of 70 SNPs in R6M168, 64 in R6M101 and 62 in R6M87. To distinguish mutations causing patAB overexpression from natural polymorphisms between the donor strains and the recipient, we transformed R6 with targeted PCR amplimers from this region in M168, M101 and M87, and selected for ethidium bromide-resistant transformants (Figure 2b). We focused on the patA and patB genes themselves due to the considerable overlap of non-contiguous recombinant regions covering these genes in the three transformants. We obtained ethidium bromide-resistant transformants using an amplimer corresponding to the patA gene from all three donor strains. No ethidium bromide-resistant transformants were obtained with amplimers corresponding to patB. Transformation with further PCR amplimers corresponding to smaller segments of patA localized the mutations conferring ethidium bromide resistance to a region between genomic positions 1 865 645 and 1 865 963, corresponding to the intergenic region between patA and the upstream gene hexA in all three donor strains.

The region identified was examined in more detail. In each transformant, the identified region contained one SNP relative to R6. Relative to the start codon of patA, these were C(−33)T in R6M168, A(−47)C in R6M101 and G(−46)A in R6M87. A putative attenuator structure, consisting of a Rho-independent terminator, anti-terminator and anti-anti-terminator, was predicted upstream of patA using the Ribex server.22 The three identified mutations were all located within the terminator loop of this putative structure (Figure 2c). The mutation found in R6M87 occurred in the same position as the G–T mutation identified in the two previous studies;9,11 however, the nucleotide substitution in our strain was G–A.

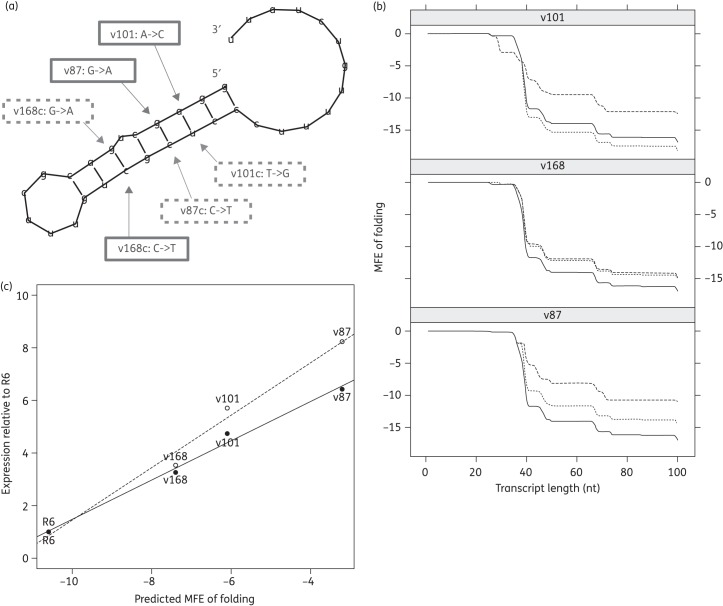

Identified mutations are predicted to reduce the stability of the Rho-independent terminator by disrupting base pairing

The G–T mutation identified previously was predicted to reduce the stability of terminator loop folding, leading to increased transcription of the downstream gene. To predict whether our mutations were likely to have the same effect, we used the RNAfold program from the Vienna RNA suite to predict the RNA structure (Figure 3a) and determine the folding energy of WT and mutated terminator structures (Figure 3b). Introduction of any of the three mutations identified in our transformants increased the predicted free energy of folding of the terminator structure relative to WT (Figure 3b). The different mutations were predicted to destabilize the terminator to differing degrees. There was a strong positive correlation between predicted folding energy of the terminator and levels of expression of both patA (R2 = 0.98) and patB (R2 = 0.98) as measured by qRT–PCR (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Structure of Rho-independent transcriptional terminator predicted by the RNAfold program from the Vienna RNA suite. (a) Predicted terminator structure. Mutations incorporated into pBAV1K-gfp82 constructs v101, v168 and v87 are indicated by solid boxes. Further mutations introduced in constructs v101c, v168c and v87c to attempt to restore base pairing are indicated by dashed boxes. (b) Folding energy of nascent patA transcript, predicted by RNAfold for WT (solid lines), mutant (v101, v168 and v87; dashed lines) and complemented (v101c, v168c and v87c; dotted lines) leader sequences. The nascent transcript was extended stepwise from the predicted patA transcription start site 67 bp upstream of the patA start codon. (c) Correlation between predicted stability of the patA transcript at 67 nt and expression of patA (solid line) and patB (dashed line) relative to R6 as measured by qRT–PCR.

Mutations disrupting terminator structure lead to increased transcription of a downstream GFP reporter

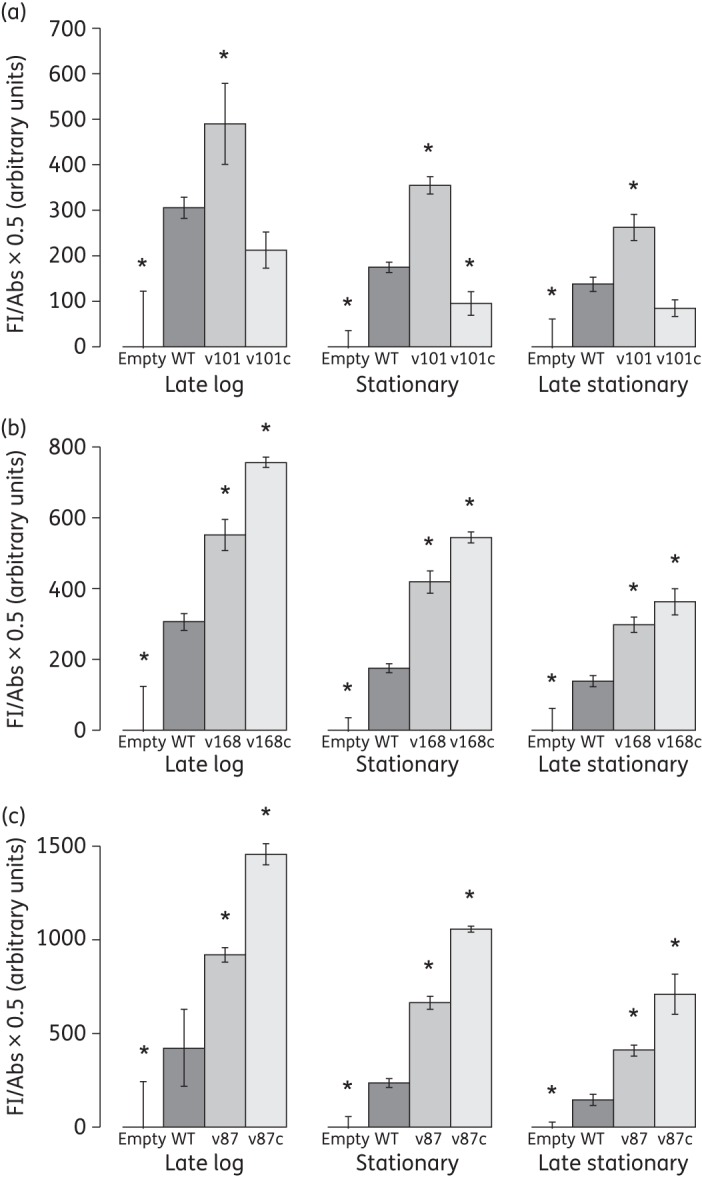

It was predicted that reduced stability of the terminator loop would increase transcription of patAB, by increasing transcriptional read-through into the patA coding sequence.11 However, this had not been experimentally demonstrated. To investigate this, we synthesized four DNA fragments corresponding to the patA upstream region (−146 to −13 bp), flanked by restriction sites. One fragment corresponded to the WT (R6) sequence, and the remaining three introduced the mutations C(−33)T (v168), A(−47)C (v101) and G(−46)A (v87). These were cloned upstream of a promoter-less GFP allele in a plasmid named pBAV1K-gfp82, derived from pBAV1K-t5-gfp (construction described in the Materials and methods section). The resulting constructs were transformed into R6 cells and transformants selected using 100 mg/L kanamycin. Fluorescence from each construct was measured during growth of the strains in BHI broth. Compared with a strain carrying pBAV1K-gfp82 empty vector, the pBAV1K-gfp82-WT construct produced consistently higher fluorescence throughout the growth cycle (Figure 4). Introduction of the terminator mutations (constructs pBAV1K-gfp82-v168, pBAV1K-gfp82-v101 and pBAV1K-gfp82-v87) resulted in a significant 1.5- to 3-fold increase in fluorescence in all three cases after 2.5, 3.5 and 5.5 h of growth, respectively, representing late-log, stationary and late-stationary phases, respectively (Figure 4; P < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence measured from pBAV1K-gfp82 reporter plasmid containing WT and mutant patA leader sequences during late-log (2.5 h), stationary (3.5 h) and late-stationary (5.5 h) phases of growth. Bars represent the fluorescence of pBAV1K-gfp82-WT and (a) v101 and v101c, (b) v168 and v168c and (c) v87 and v87c, adjusted to a standard OD600 of 0.5, relative to the fluorescence of empty pBAV1K-gfp82 vector. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three biological replicates. *Fluorescence significantly different from WT; P < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test.

Restoration of terminator stem–loop stability leads to a reduction in transcription of the downstream reporter

The mutations investigated were predicted to cause patAB overexpression by disrupting the base pairing of the terminator stem–loop structure. Restoration of this base pairing should therefore restore termination and reduce transcription of the downstream gene. To investigate this prediction, for each mutant terminator we synthesized a further DNA fragment in which we attempted to re-form the predicted WT terminator structure by mutating the opposing base in the stem–loop such that Watson−Crick base pairing was restored (Figure 3a). This gave constructs pBAV1K-gfp82-v168c [C(−33)T and G(−43)A], pBAV1K-gfp82-v101c [A(−47)C and T(−30)G] and pBAV1K-gfp82-v87c [G(−46)A and C(−31)T]. In the case of v101c, mutating the opposing base in the structure resulted in a reduction of the predicted folding energy of the terminator (determined by RNAfold) back to below WT levels (Figure 3b). However, this was not the case for v168c and v87c, where mutation of the opposing base did not substantially reduce folding energy. Our model of the RNA folding was very simplistic and there may be further stabilizing interactions beyond simple base pairing that we did not take into account. Consistent with the predictions of folding energy, GFP fluorescence from pBAV1K-gfp82-v101c was significantly reduced compared with pBAV1K-gfp82-v101 at all tested growth stages (Figure 4a; P < 0.05), and instead was either the same as or significantly lower than WT fluorescence. Fluorescence from pBAV1K-gfp82-v168c and pBAV1K-gfp82-v87c was not reduced by the attempt to restore base pairing, and remained significantly higher than WT at all tested growth stages (Figure 4b and c; P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we have identified three novel SNPs causing up-regulation of patAB in S. pneumoniae. All three mutations were located in a Rho-independent transcriptional terminator located directly upstream of patA. Combined with the G−T mutation identified in two previous studies,9,11 four mutations have now been observed in this terminator structure, providing strong support for the hypothesis that this terminator structure is important for suppression of patAB expression and consequent fluoroquinolone resistance.

Rho-independent terminators consist of an RNA stem–loop structure that arrests progression of the transcription complex, followed by a uracil-rich region that promotes dissociation of the polymerase from the DNA.23 Mutations disrupting the stem–loop structure are therefore predicted to reduce polymerase pausing, and therefore dissociation, promoting continued transcription of the downstream gene. This hypothesis was previously proposed to explain the observed increase in patAB expression in terminator mutants;11 however, this had not been experimentally demonstrated. Here, we have used transcriptional fusion of the patA upstream region with a GFP reporter to demonstrate that terminator mutations do lead to increased transcriptional read-through into a downstream gene.

Fluorescence from the pBAV1K-gfp82-WT construct was consistently higher than from the empty vector at all growth stages tested. This suggests that patAB is transcribed at a basal level throughout growth. Disruption of the terminator stem–loop by all three mutations tested then increased this further. Two observations indicated that the stem–loop structure is important for transcriptional control. Firstly, there was a very strong correlation between predicted minimum free energy of the WT and mutant terminator structures and patAB expression level. Secondly, restoration of the stem–loop structure in the v101 variant by mutation of the opposing base in the structure reduced fluorescence back to WT levels. Taken together, these results suggest that the mutations increase downstream gene expression by reducing Rho-independent termination, as opposed to another mechanism, such as mutation of a transcription factor binding site.

It has previously been observed that isolates overexpressing patAB can be selected easily by exposure to the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin or the efflux inhibitor reserpine.7,24 As demonstrated here, patAB overexpression can be conferred by any one of a number of mutations that disrupt the upstream terminator, which may explain how patAB-overexpressing mutants can be selected so reliably.

Disruption of the patA upstream terminator provides an explanation for selection of constitutive patAB expression on exposure to antibacterial agents. However, it does not explain the inducible patAB expression on exposure to fluoroquinolones or DNA-damaging agents that has been previously observed. Here, we observed that the Rho-independent transcriptional terminator is predicted to be part of a transcriptional attenuator, consisting of terminator, anti-terminator and anti-anti-terminator stem–loops. Transcriptional attenuation is a prevalent regulatory strategy in Gram-positive bacteria.25 Transcriptional attenuators are RNA leader sequences that can fold into two or more mutually exclusive stem–loops, one of which is a Rho-independent terminator, and this folding can be influenced by a variety of regulatory signals.26 Although it was not investigated in this study, it is conceivable that the presence of fluoroquinolones or DNA damage may result in induction of patAB expression via a regulatory signal that reversibly disrupts the patA upstream terminator. Recently, a similar transcriptional attenuator was found to be involved in up-regulation of the BmrCD ABC transporter in Bacillus subtilis in response to ribosome-targeting antibiotics.27 Similarly, expression of another B. subtilis ABC transporter gene associated with antibiotic resistance, bmrA, has been shown to be increased by an upstream mutation that increases mRNA stability.28 When combined with our results, these findings raise the intriguing possibility that transcriptional attenuation may be a common method of control of ABC transporter family efflux pumps in Gram-positive bacteria.

In this study, we located the mutations causing patAB overexpression using a whole-genome transformation approach that exploited the natural transforming ability of S. pneumoniae. This approach was similar to that used by Billal et al.9 to separate mutations causing linezolid resistance from bystander mutations. We used natural polymorphisms between the donor strains and the R6 recipient as a marker to distinguish regions of the genome that have undergone recombination, and therefore may contain mutations of interest. As a by-product of this, we observed primary and secondary recombinations in the same cell, as recently described by Croucher et al.11 We also saw multiple contiguous recombinations from the same piece of DNA, as was also described by Croucher et al.11 In this study, all three mutations were ultimately found to be located in the upstream region of patA, so they could have been discovered by other methods. However, the method used here has the potential to locate causative mutations anywhere in the genome, such as in a regulator encoded elsewhere. Due to recent improvements in whole-genome sequencing technology, meaning that many bacterial strains can be multiplexed in a single Illumina lane for a relatively low cost, this method could therefore be used to screen a larger library of patAB-overexpressing isolates to identify other components of the patAB regulatory pathway.

Funding

This work was supported by a Medical Research Council Doctoral Training Grant (grant number DKAA GAS0025) to L. J. V. P.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

References

- 1.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuller JD, Low DE. A review of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection treatment failures associated with fluoroquinolone resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:118–21. doi: 10.1086/430829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janoir C, Zeller V, Kitzis MD, et al. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2760–4. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan XS, Ambler J, Mehtar S, et al. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–6. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson G, Doyle T, Lynch A. Use of an efflux-deficient Streptococcus pneumoniae strain panel to identify ABC-class multidrug transporters involved in intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4781–3. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4781-4783.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrer E, Schad K, Satoh AT, et al. Involvement of the putative ATP-dependent efflux proteins PatA and PatB in fluoroquinolone resistance of a multidrug-resistant mutant of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:685. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.685-693.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garvey MI, Piddock LJV. The efflux pump inhibitor reserpine selects multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains that overexpress the ABC transporters PatA and PatB. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1677–85. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01644-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boncoeur E, Durmort C, Bernay B, et al. PatA and PatB form a functional heterodimeric ABC multidrug efflux transporter responsible for the resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones. Biochemistry. 2012;51:7755–65. doi: 10.1021/bi300762p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billal DS, Feng J, Leprohon P, et al. Whole genome analysis of linezolid resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae reveals resistance and compensatory mutations. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:512. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Opijnen T, Camilli A. A fine scale phenotype-genotype virulence map of a bacterial pathogen. Genome Res. 2012;22:2541–51. doi: 10.1101/gr.137430.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Croucher NJ, Mitchell AM, Gould KA, et al. Dominant role of nucleotide substitution in the diversification of serotype 3 pneumococci over decades and during a single infection. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrer E, Satoh AT, Johnson MM, et al. Global transcriptome analysis of the responses of a fluoroquinolone-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae mutant and its parent to ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:269. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.269-278.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Garch F, Lismond A, Piddock LJV, et al. Fluoroquinolones induce the expression of patA and patB, which encode ABC efflux pumps in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2076–82. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews JM. The development of the BSAC standardized method of disc diffusion testing. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48(Suppl 1):29–42. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryksin AV, Matsumura I. Rational design of a plasmid origin that replicates efficiently in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bumann D, Valdivia RH. Identification of host-induced pathogen genes by differential fluorescence induction reporter systems. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:770–7. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Höner Zu Siederdissen C, et al. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2011;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garvey MI, Baylay AJ, Wong RL, et al. Overexpression of patA and patB, which encode ABC transporters, is associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:190–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00672-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piddock LJV, Johnson MM, Simjee S, et al. Expression of efflux pump gene pmrA in fluoroquinolone-resistant and -susceptible clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:808–12. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.808-812.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gusarov I, Nudler E. The mechanism of intrinsic transcription termination. Mol Cell. 1999;3:495–504. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80477-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avrain L, Garvey M, Mesaros N, et al. Selection of quinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae exposed in vitro to subinhibitory drug concentrations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:965–72. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naville M, Gautheret D. Transcription attenuation in bacteria: theme and variations. Brief Funct Genomics. 2010;9:178–89. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elq008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henkin TM, Yanofsky C. Regulation by transcription attenuation in bacteria: how RNA provides instructions for transcription termination/antitermination decisions. Bioessays. 2002;24:700–7. doi: 10.1002/bies.10125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reilman E, Mars RAT, van Dijl JM, et al. The multidrug ABC transporter BmrC/BmrD of Bacillus subtilis is regulated via a ribosome-mediated transcriptional attenuation mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:11393–407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krügel H, Licht A, Biedermann G, et al. Cervimycin C resistance in Bacillus subtilis is due to a promoter up-mutation and increased mRNA stability of the constitutive ABC-transporter gene bmrA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;313:155–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]