Abstract

Purpose of review

To discuss why HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) persist despite apparently effective HIV suppression by highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Recent findings

As many as 50% of HIV-infected individuals suffer from HAND despite ART suppression of HIV replication to apparently undetectable levels in most treated individuals. Prior to ART, HIV-associated dementia (HAD), the severest form of HAND, affected ~20% of infected individuals; HAD now affects only ~2% of ART-treated persons, while less severe HAND forms persist. Recent studies link persistent immune activation, inflammation, and viral escape/blipping in ART-treated individuals, as well as co-morbid conditions, to HIV disease progression and increased HAND risk. Despite sustained HIV suppression in most ART-treated individuals, indicated by routine plasma monitoring and occasional CSF monitoring, ‘blips’ of HIV replication are often detected with more frequent monitoring, thus challenging the concept of viral suppression. Although the causes of HIV blipping are unclear, CSF HIV blipping associates with neuroinflammation and, possibly, CNS injury. The current theory that macrophage-tropic HIV strains within the CNS predominate in driving HAND and these associated factors is now also challenged.

Summary

Protection of the CNS by ART is incomplete, probably due to combined effects of incomplete HIV suppression, persistent immune activation, and host co-morbidity factors. Adjunctive therapies to ART are necessary for more effective protection.

Keywords: HAND, HIV, brain, viral blip, HIV blip, inflammation

Introduction

HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND) remain prevalent despite apparently effective suppression of HIV replication by ART in most treated individuals [1**,2**,3**]. The underlying neuropathological processes in the brain that contribute to neurological dysfunction in HAND in the era of ART are probably significantly attenuated by such therapy, resulting in a more protracted and less severe clinical course of HAND. Although fulminant encephalitis is now distinctly uncommon in HIV infection, CSF biomarkers of neuroinflammation and brain neuroimaging biomarkers of glial activation and neuronal injury are frequently detected in virally-suppressed individuals. Partial protection against HAND by ART confirms a direct and possibly incomplete link to HIV replication; however longitudinal studies in ART-experienced cohorts indicate surprisingly frequent episodes of CNS viral escape (HIV blipping) in those thought to have complete viral suppression. This suggests a persistent link between CNS HIV replication, immune activation, inflammation and neurological dysfunction that escapes full suppression by current ART. This review will discuss recent studies that investigate these links and identify several gaps in our understanding of HAND neuropathogenesis, including the roles for chronic inflammation, viral blipping, and macrophage-tropic HIV strains within the CNS. Contributing HAND co-morbidity factors are discussed in other reviews in this issue and in several other recent reviews [4*,5*].

CNS HIV infection, persistent immune activation, inflammation and HAND

Early brain infection by HIV is a consistent consequence of systemic HIV infection [6] and CSF HIV RNA levels correlate with severity of neurocognitive dysfunction in ART-naïve subjects, thus linking CNS dysfunction to CNS HIV replication in those individuals (reviewed in [1**,4*]). Perivascular macrophages are the major CNS site of productive HIV replication, although endogenous brain microglia and astrocytes (up to ~15% infection rate) can also harbor virus [7*]. Associated with both early and chronic brain infection is amplification of pro-inflammatory cascades, production of reactive oxygen species, expression of HIV proteins, oxidative stress, and increased production of glutamate and other excitotoxins, all of which have been linked directly or indirectly to neuronal injury and dysfunction [8*]. These links were strongly established in the pre-ART era, but the validity of these links in individuals on suppressive ART is now being challenged, as detection of CSF HIV RNA is more rare and often not correlated with neurocognitive dysfunction in those individuals (reviewed in [2**]). However, there is no credible evidence that ART can irreversibly suppress or clear HIV from or within the CNS. Furthermore, interruption of ART can be associated with viral rebound in the CSF, neuronal injury, and worsened neurocognitive performance [9–11]. With recent studies confirming surprisingly high rates of CSF viral escape (blipping) in individuals felt to be in a state of HIV suppression, a role for persistent CNS HIV infection and replication, even if intermittent, in HAND pathogenesis in ART-experienced patients appears likely [12**]. Equally likely is an association of HIV blipping with immune activation.

Chronic immune activation in HIV infection results in part from increased microbial translocation across a damaged gastrointestinal tract, which shows depletion of gut-associated lymphoid tissue and other structural changes (reviewed in [13**]). Exposure of circulating PBMC to these translocated microbial products, including LPS results in monocyte activation, which is indicated by elevated blood levels of soluble CD14 (sCD14), sCD163, and monocyte-associated CD14 and CD16 [14*]. Notably, elevated levels of circulating CD16+ monocytes, CD14+ monocyte HIV DNA content, sCD14, and sCD163 associated with microbial translocation correlate with an increased risk for HAND [15*], indicating a central role for monocyte activation in pathogenesis. Recent studies have presented a provocative microbial translocation hypothesis: the damaged gastrointestinal tract in HIV-infected individuals harbors more pathogenic microbial populations than that of non-infected individuals [16**]. Therefore, based on accumulating evidence for associations between the gut microbiome and nervous system disorders such as multiple sclerosis and Guillain Barre disease [17**], it is interesting to speculate that certain gut microbiomes could associate with CNS disease progression in HIV infection. This will certainly be a key question for future investigations, and the gut microbiome may ultimately represent another targetable ‘host factor’ for HAND prevention.

In summary, even in ART-treated individuals with excellent viral suppression the persistence of immune activation, particularly monocyte/macrophage activation in the systemic circulation and CSF correlates with an increased risk for HAND. The pathophysiological factors responsible for establishing and maintaining a state of immune activation are important considerations for HAND prevention strategies.

HIV ‘blipping’ as a neuroinflammation-associated risk factor for HAND

HIV ‘blips’ are thought to represent new rounds of HIV replication that result in increased VL above the established lowest level of quantifiable HIV RNA. Viral (HIV) blips are defined as spontaneous expression of viral RNA copies (plasma, CSF) in individuals on ART with sustained antecedent undetectable VLs with return to undetectable levels [18]. CSF discordant blipping is generally defined as a higher RNA copy level of ≥ 0.5 log in the CSF in comparison with plasma. An overall plasma HIV blip (> 50 HIV RNA copies/ml) frequency of ~25% has been demonstrated in an observational cohort study (n=3550 virally suppressed patients) [18]. Several causes of blipping are proposed, including differences in VL assay sensitivity [19] and factors affecting HIV replication (ART adherence, immune activation, viral resistance, among others) [18,20*,21]. A role for blips in contributing to increased immune activation and accelerated disease progression has been suggested [20*] although this has been challenged [22].

The significance of viral blips remains undetermined, and their possible association with HAND is under increasing investigation [21*,23,24]. Emerging evidence supports a role for blipping in promoting increased immune activation in the systemic circulation and CNS compartment, which is linked with development of HAND. A link between plasma HIV blips and systemic immune activation has recently been demonstrated in a prospective study of matched blippers and non-blippers [25**]. The study involved 82 individuals with plasma viral blips (VL > 50 and <1000 copies/ml after at least 180 days at undetectable VL on ART) matched with 82 cohort controls without blips. The patients with plasma viral blips after suppressive ART showed increased T cell activation (CD3+HLA-DR+ T lymphocyte level) compared with patients without blips. This suggests that plasma blips might identify those patients at increased risk for immune activation associated with disease progression. Additionally, Castro et al [20*] retrospectively analyzed responses in a cART interruption study and found that subjects with plasma blips above 200 copies/ml prior to cART interruption had lower CD4+ T cell levels under cART, and poorer CD4+ T cell recovery and increased expression of immune activation markers after cART interruption. This study provided evidence not only that blipping could drive immune activation, but also that the magnitude of the blip can determine future virological failure.

Evidence suggesting that blips might merely maintain an established state of immune activation rather than increase immune activation has also been presented. Benmarzouk-Hidalgo et al [22] studied patients who were switched to simplification treatment of darunavir/ritonavir monotherapy for 24 months after a 6 month period of sustained HIV suppression with combination ART. Outcome groups were assigned as those with continuous aviremia, blips (one plasma VL > 50 copies/ml, preceded and followed by undetectable VL) and intermittent viremia (episodes of VL > 20 copies/ml without blips or failure). Virological failure was defined as two consecutive VL > 200 copies/ml. Only virological failure and not blipping or intermittent viremia was associated with increased immune activation (CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte activation, primarily TCM CD4+ T lymphocytes) from the baseline status. In addition, monocyte activation (plasma sCD14 levels) remained unchanged in the blipping and intermittent viremia groups, while decreasing in the aviremic group. Thus, sustained aviremia associated with significant decreases in activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and monocytes while virological failure associated with increases in activation of each T lymphocyte subset. Those individuals with blipping and intermittent viremia maintained their previous levels of immune activation. These studies add to the growing evidence indicates that suppression of viral blipping could help in controlling and/or suppressing immune activation in many HIV-infected individuals and they support the importance of determining these associations in the CNS.

Defining the possible associations between blipping in the CNS compartment and increased risk for HAND is critical; HAND persists in HIV-suppressed populations and blipping is surprisingly common in such populations [18,26]. A study of 200 HIV-infected individuals with sustained HIV suppression (median 48 months; range 3.2–136.6) found an overall prevalence of HAND of 69% including a 19% prevalence of significant functional neurological impairment (17% MND, 2% HAD) [27]. Although not designed to detect viral blips, this study suggests persistence of neurological dysfunction in individuals considered to be appropriately treated (HIV suppression) with ART. Given the prevalence of blips in other studies, it raises the question of whether plasma and/or CSF viral blips might contribute to this risk for HAND in suppressed populations.

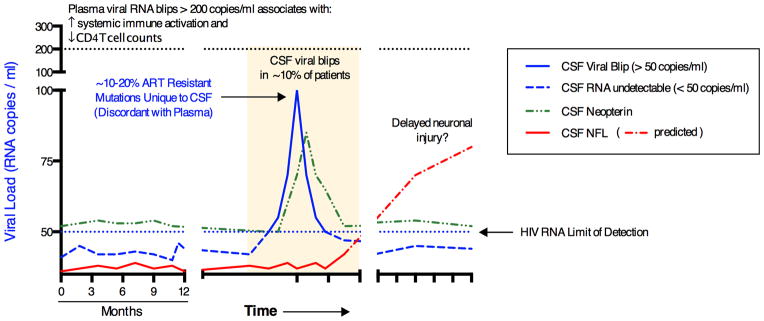

Recently published and ongoing, unpublished studies directly address the relationships between CSF HIV blipping, inflammation and HAND risk. Eden et al [23] found that ~10% of 69 neurologically normal, HIV ‘suppressed’ patients had detectable CSF HIV RNA, consistent with ongoing HIV replication in the CNS compartment. Furthermore those with detectable CSF RNA had significantly higher CSF expression of markers of monocyte activation (neopterin) and also a longer duration of ART treatment. Follow up studies have indicated that the elevated CSF neopterin levels are not associated with neuronal injury (elevated CSF neurofilament (NFL) levels) at the time of sampling (Figure 1), but whether these blips will associate with future risk for neuronal injury remains to be determined [28*]

Figure 1. Hypothetical time course of CSF viral blips, neuroinflammation, and neuronal injury.

Diagram outlining the postulated temporal associations between CSF HIV viral blips, neuroinflammation (CSF neopterin), and neuronal injury (CSF neurofilament light chain, NFL).

Because blips can associate with increased duration of ART and the emergence of ART resistance [23,29], determining the frequency of ART resistance mutations in blippers is critical for ART management of HAND risk. Canestri et al [21] found ART resistance mutations in 7 of 8 CSF specimens from CSF blippers in a small group (n=11) of HIV suppressed (~18 months) patients with neurological symptoms. Ten of the patients had CSF pleocytosis, indicating a strong association between CSF blipping and inflammation. Notably, however, the patients were not evaluated by HAND criteria and so the relationship to HAND is speculative. Additional evidence for emergence of ART resistance in CSF blippers is provided by the ongoing UK PARTITION STUDY of CNS ART penetration [30*]. Three of three CSF specimens tested from a cohort of 38 CSF blippers showed reverse transcriptase resistance mutations, which supports the earlier demonstration and previous reports of a high prevalence of drug resistance in CSF blippers [12**]. Prospective monitoring for drug resistance in the CSF is necessary to determine the risk for developing HAND.

In summary, the argument for a causal relationship between HIV blips, increased immune activation and risk for disease progression in both systemic and CNS compartments is increasing in strength. A role for intermittent HIV replication within the CNS in HAND pathogenesis in virally ‘suppressed’ ART-experienced patients appears likely. As average ART duration increases, the risks of recurrent blipping will likely become more apparent, and the challenges of monitoring blipping in the CSF as well as plasma will need to be resolved.

CNS HIV tropism, adaptation, and HAND risk: challenging conventional thinking

Establishing a CNS HIV reservoir within the macrophage and microglial lineages by macrophage-tropic (M-tropic) strains, conventionally defined as those that infect both T lymphocytes and macrophages, has been considered a necessary, but not sufficient precursor to the development of HAND. The detection of CSF HIV blipping independent from that detected in plasma is assumed to reflect transient activation of HIV replication of M-tropic strains from these CNS cellular reservoirs. Individuals with the severest form of HAND, HIV-associated dementia (HAD) often have genetically distinct M-tropic variants in their CSF that are not found in the plasma [31], consistent with a central role for replication of M-tropic strains within the CNS in the pathogenesis of HAND.

However, recent evidence also suggests that not only M-tropic strains but also ‘T cell-tropic’ strains, conventionally defined as those that infect T lymphocytes but not macrophages, can be isolated from the CNS and that each contributes to the development of HAD [31]. Schnell et al [31] found genetically compartmentalized T cell- and M-tropic HIV populations within the CSF that were distinct from those found in the plasma of eight of eight subjects with neurocognitive dysfunction (seven HAD, one milder dysfunction). Three subjects had compartmentalized T cell-tropic populations and five had compartmentalized M-tropic populations. This study challenged the established hypothesis that M-tropic strains are primarily responsible for driving the pathogenesis of HAND.

More recently, the same group further analyzed genetic and phenotypic characteristics cloned env sequences of paired CSF/plasma isolates from five individuals and confirmed that CSF-derived viruses segregated into two distinct groups: M-tropic and T cell tropic and, based upon their relative ability to infect cell lines engineered to express tightly-controlled low- and high-level CD4 surface expression respectively [32*]. This well-defined segregation of naturally-occurring HIV phenotypes does not strictly predict the conventional M-tropic and T cell-tropic infection patterns in primary monocyte-derived macrophages or primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Furthermore, how this phenotype segregation might apply to infection of CD4-negative cell types, such as astrocytes, is unanswered. Thus, the issue of the distribution of HIV strains within different cell lineages/reservoirs within the CNS and the relevance of each to HAND neuropathogenesis has been re-opened. This is particularly relevant to persistence of HIV within the CNS in ART-suppressed patients, the genesis of CSF HIV blips linked to neuroinflammation, and for consideration of CNS HIV eradication strategies.

Finally, studies of CNS HIV compartmentalization have focused almost exclusively on adults with HIV subtype B infection, until recently. A particularly noteworthy study of young Malawian children (n=43) with vertically-acquired HIV subtype C showed that such compartmentalization occurs in up to 50% of children reaching age three [33]. This pertained to env evolution of early T cell-tropic strains within the CNS to later M-tropism or through CNS sequestration of a transmitted M-tropic variant from the mother. Notably, the M-tropic compartmentalized strains appeared after 18 months of age and were associated with higher relative CSF viral loads; this suggests growth in macrophages and/or microglia. It also further supports the importance of determining the phenotype/genotype characteristics of viral species in those individuals experiencing CSF HIV blips to identify likely reservoirs accounting for those blips.

Thus, our understanding of the role for HIV tropism in determining early events leading to CNS invasion, establishment of viral reservoirs, and long-term selection pressures within the CNS continues to evolve. We are re-examining our long-held belief that macrophage tropism is the predominant HIV determinant of neurovirulence driving HAND, although it appears certain that it is a common factor in HIV neuropathogenesis. Nonetheless, HIV neuropathogenesis might not be an exclusive function of M-tropic strains, and the importance of thoroughly evaluating early events and the role of T cell tropism in CNS infection in both adults and children/neonates is critical for optimizing treatment strategies and achieving better neuroprotection.

Conclusions

HIV associated neurocognitive disorders have persisted despite the effectiveness of ART in limiting HIV disease progression. Strong evidence now links persistent immune activation resulting from microbial translocation with systemic disease progression, and emerging evidence suggests a similar link to HAND. Suppressing this immune activation in both systemic and CNS compartments appears likely to limit disease progression beyond that limited by ART. Nonetheless, HIV suppression is incomplete in a disturbingly high proportion of ART-treated individuals, as estimated by a ~25% overall rate of plasma HIV blipping. Improvements in ART regimens (and certainly other contributing factors) and patient monitoring can probably reduce this failure rate and limit both systemic and CNS disease progression. Finally, we must more fully understand the phenotypes and tropism of HIV strains entering the CNS and establishing reservoirs. An exclusive role for macrophage-tropic strains has been challenged and this must be addressed, as tropism largely determines HIV cellular reservoirs. This might be the most challenging obstacle to optimizing protection against HAND, in comparison to the challenges of chronic immune activation and plasma/CSF blipping, which can more directly be currently addressed.

Key Points.

Emerging evidence suggests a link between the persistence of systemic and CNS immune activation and the persistence of HAND in ART-treated individuals.

HIV suppression is incomplete in ~25% of ART-treated individuals and such plasma HIV blipping might identify those patients at increased risk for immune activation associated with disease progression and future virologic failure.

Approximately 10% of HIV ‘suppressed’ patients show evidence of ongoing, intermittent CNS replication that associates with increased markers of neuroinflammation

Both M-tropic and T-cell tropic HIV might play a role in CNS invasion and establishment of CNS viral reservoirs that can lead to HAND.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01MH095671 (DLK), R01MH104134 (DLK), and F30MH102120 (AJG).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Papers of interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1**.Manji H, Jager HR, Winston A. HIV, dementia and antiretroviral drugs: 30 years of an epidemic. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:1126–1137. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304022. This is a comprehensive review of the cumulative data concerning HAND from the past 30 years that is up-to-date and very informative. Relevant features of the clinical diagnosis, radiological findings, effects of ART, viral compartmentalization and escape, and chronic inflammation are succintly summarized and discussed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2**.Price RW, Spudich SS, Peterson J, et al. Evolving Character of Chronic Central Nervous System HIV Infection. Semin Neurol. 2014;34:7–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372337. The authors integrate recent and newer observations in early CNS entry events, chronic CNS infection, and HIV tropism in primary immune cells to support hypotheses about the evolution of neuropathological events leading to HAND. This insightful review ends with useful recommendations for monitoring individuals to determine risk for HAND. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3**.Canizares S, Cherner M, Ellis RJ. HIV and Aging: Effects on the Central Nervous System. Semin Neurol. 2014;34:27–34. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372340. This is a review of studies (some of the authors’ unpublished work) that describe co-morbidity factors in HIV-infected individuals that can worsen neurocognitive functioning: aging, APOEe4 allele status, metabolic syndrome, and others. The authors thoughtfully critique published studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4*.Clifford DB, Ances BM. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:976–986. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70269-X. The evidence that viral control in the CNS is still an elusive goal for HAND prevention in addition to major co-morbidity factors is convincingly discussed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5*.Gill AJ, Kolson DL. Chronic Inflammation and the Role for Cofactors (Hepatitis C, Drug Abuse, Antiretroviral Drug Toxicity, Aging) in HAND Persistence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0210-3. This review emphasizes co-morbidity factors for HAND, with specific discussion about current opportunities to treat HCV with newly approved medications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valcour V, Chalermchai T, Sailasuta N, et al. Central nervous system viral invasion and inflammation during acute HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:275–282. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.Burdo TH, Lackner A, Williams KC. Monocyte/macrophages and their role in HIV neuropathogenesis. Immunol Rev. 2013;254:102–113. doi: 10.1111/imr.12068. Studies of HIV and SIV infection and their similarities support the value of the SIV primate model in elucidating the functional roles for monocytes/macrophages in neuropathogenesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8*.Uzasci L, Nath A, Cotter R. Oxidative stress and the HIV-infected brain proteome. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:1167–1180. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9444-x. This unique and comprehensive review documents the history and development of the evidence for a central role for oxidative stress in the neuropathogenesis of CNS HIV infection, with particular emphasis on the biochemistry of protein modifications in the brain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Childers ME, Woods SP, Letendre S, et al. Cognitive functioning during highly active antiretroviral therapy interruption in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Neurovirol. 2008:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13550280802372313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monteiro de Almeida S, Letendre S, Zimmerman J, et al. Dynamics of monocyte chemoattractant protein type one (MCP-1) and HIV viral load in human cerebrospinal fluid and plasma. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;169:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisslen M, Rosengren L, Hagberg L, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid signs of neuronal damage after antiretroviral treatment interruption in HIV-1 infection. AIDS Res Ther. 2005;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12**.Stam AJ, Nijhuis M, van den Bergh WM, Wensing AM. Differential genotypic evolution of HIV-1 quasispecies in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma: a systematic review. AIDS Rev. 2013;15:152–161. This is a very informative, comprehensive, and up-to-date summary of the published data concerning HIV quasispecies and ART resistance in the CNS. The conclusion that CNS HIV compartmentalization, independent evolution of ART resistance, and varied HIV co-receptor tropism dominated by R5-tropism in chronic infection is strongly supported. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13**.Marchetti G, Tincati C, Silvestri G. Microbial translocation in the pathogenesis of HIV infection and AIDS. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:2–18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00050-12. The processes of microbial translocation across the gut barrier, host immune responses, and the implications for pathogenesis of SIV and HIV infection are thoughtfully presented. Interesting therapeutic considerations are also discussed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Klatt NR, Funderburg NT, Brenchley JM. Microbial translocation, immune activation, and HIV disease. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.09.001. The possible mechanisms of immune activation related to the causes of microbial translocation are particularly well addressed. Interesting therapeutic considerations are also discussed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15*.Valcour VG, Ananworanich J, Agsalda M, et al. HIV DNA reservoir increases risk for cognitive disorders in cART-naive patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070164. This study links the circulating CD14+ monocyte HIV DNA burden to CSF immune activation markers, brain injury as demonstrated by MR spectroscopy, and HAND, and rationally discusses causal relationships. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Mutlu EA, Keshavarzian A, Losurdo J, et al. A compositional look at the human gastrointestinal microbiome and immune activation parameters in HIV infected subjects. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003829. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003829. The gut microbiome in HIV+ and HIV− individuals shows less genetic diversity, loss of commensal bacteria, and increased numbers of some potential pathogenic bacterial taxa in HIV+ individuals. This supports the hypothesis that changes in the gut microbiome due to HIV infection are associated with pathogenic immune activation and it validates several earlier studies. Therapeutic implications are discussed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Wang Y, Kasper LH. The role of microbiome in central nervous system disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;38:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.12.015. This is a particularly informative review of the links between the gut microbiome and neurological disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and autism. This information can probably inform investigations of possible associations between the gut microbiome and HAND. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grennan JT, Loutfy MR, Su D, et al. Magnitude of virologic blips is associated with a higher risk for virologic rebound in HIV-infected individuals: a recurrent events analysis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:1230–1238. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray JM, Zaunders JJ, Koelsch KK, et al. Short communication: HIV blips while on antiretroviral therapy can indicate consistently detectable viral levels due to assay underreporting. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:1621–1625. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Castro P, Plana M, Gonzalez R, et al. Influence of episodes of intermittent viremia (“blips”) on immune responses and viral load rebound in successfully treated HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:68–76. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0145. Individuals with HIV blips exceeding 200 copies/ml demonstrate lower CD4 Tcell counts, higher levels of immune activation markers during ART, and a higher viral rebound after treatment interruption, suggesting a role for blipping in disease progression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canestri A, Lescure FX, Jaureguiberry S, et al. Discordance between cerebral spinal fluid and plasma HIV replication in patients with neurological symptoms who are receiving suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:773–778. doi: 10.1086/650538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benmarzouk-Hidalgo OJ, Torres-Cornejo A, Gutierrez-Valencia A, et al. Immune activation throughout a boosted darunavir monotherapy simplification strategy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eden A, Fuchs D, Hagberg L, et al. HIV-1 viral escape in cerebrospinal fluid of subjects on suppressive antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1819–1825. doi: 10.1086/657342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khoury MN, Tan CS, Peaslee M, Koralnik IJ. CSF viral escape in a patient with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. J Neurovirol. 2013;19:402–405. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25**.Zoufaly A, Kiepe J, Hertling S, et al. Immune activation despite suppressive highly active antiretroviral therapy is associated with higher risk of viral blips in HIV-1-infected individuals. HIV Med. 2014 doi: 10.1111/hiv.12134. This carefully controlled study examined 82 patients with plasma viral blips and a matched group of 82 patients without plasma blips from the same cohort after at least 6 months of suppressive ART. HIV blipping was associated with increased expression of activated T cells (CD3+HLA-DR+), suggesting a cause/effect relationship and possible role in disease progression. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taiwo B, Bosch RJ. More reasons to reexamine the definition of viral blip during antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite longstanding suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24:1243–1250. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283354a7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Eden A, Andersson L, Fuchs D, et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Viral Blips and Persistent Escape in HIV-Infected Patients On ART. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Abstract # 445 Topics in Antiviral Medicine. 2014;22:210. This study demonstrated an association between CSF HIV blips and elevated neopterin levels in 75 ART-treated subjects, suggesting a direct link between CNS monocyte activation and viral blipping. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pozniak A, Gupta RK, Pillay D, et al. Causes and consequences of incomplete HIV RNA suppression in clinical trials. HIV Clin Trials. 2009;10:289–298. doi: 10.1310/hct1005-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Nightingale S, Group PS. HIV-1 RNA Detection in CSF in ART-Treated Subjects With Incomplete Viral Suppression in Plasma. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Abstract #442 Topics in Antiviral Medicine. 2014;22:209. In subjects with neurological signs or symptoms and unexplained plasma HIV RNA > 50 copies/ml, this study demonstrated CSF/plasma discordance in HIV RNA levels in 13% and 4/4 of these individuals showed resistance mutations in CSF but not plasma. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnell G, Joseph S, Spudich S, et al. HIV-1 replication in the central nervous system occurs in two distinct cell types. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002286. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Joseph SB, Arrildt KT, Swanstrom AE, et al. Quantification of entry phenotypes of macrophage-tropic HIV-1 across a wide range of CD4 densities. J Virol. 2014;88:1858–1869. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02477-13. This study presents an argument and experimental support for more strictly defining macrophage tropism by determining HIV strain dependence on the level of CD4 receptor expression on target cells, which has specific relevance to infection in the CNS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturdevant CB, Dow A, Jabara CB, et al. Central nervous system compartmentalization of HIV-1 subtype C variants early and late in infection in young children. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003094. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]