Abstract

Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD/SOD2) is a mitochondria-resident enzyme that governs the types of reactive oxygen species egressing from the organelle to affect cellular signaling. Here, we demonstrate that MnSOD upregulation in cancer cells establishes a steady flow of H2O2 originating from mitochondria that sustains AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) activation and the metabolic shift to glycolysis. Restricting MnSOD expression or inhibiting AMPK suppress the metabolic switch and dampens the viability of transformed cells indicating that the MnSOD/AMPK axis is critical in support cancer cell bioenergetics. Recapitulating in vitro findings, clinical and epidemiologic analyses of MnSOD expression and AMPK activation indicated that the MnSOD/AMPK pathway is most active in advanced stage and aggressive breast cancer subtypes. Taken together, our results indicate that MnSOD serves as a biomarker of cancer progression and acts as critical regulator of tumor cell metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

Advances in the understanding of the molecular basis of cancer have placed mitochondria[1] at the center of numerous abnormalities observed in tumor cell metabolism [2–4], differentiation [5], proliferation [6] and survival [7,8]. Either due to its direct impact on the cellular metabolism or its role as a hub for signal transduction, deregulation of intrinsic mitochondrial processes combined with failure to halt cell cycle progression results in the genesis and progression of tumors [9–13]. Among the many abnormal features of cancerous cells, a form of metabolism reliant on aerobic glycolysis is remarkable [4] as it enables cell survival in the near absence of oxygen and provides the necessary building blocks to support vigorous proliferation. Recently, a growing number of studies aimed at defining mechanisms of mitochondrial deregulation in cancer have indicated that a deeper understanding of tumor cell metabolism will likely impact therapeutics by enabling the development of targeted treatments with fewer complications and increased efficacy in preventing recurrence post therapy [7,14–18].

In parallel with glycolytic metabolism [19–22], high MnSOD expression [23–25] is a distinctive feature of tumors particularly notable at advanced stages [26,27]. In healthy mitochondria, MnSOD directly regulates the metabolism of superoxide radical anions generated as a by-product of the electron transport chain. In isolation, MnSOD converts the diffusion-restricted, mild-oxidant superoxide radical into the diffusible, strong oxidant hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and thereby critically changes mitochondria-driven signaling in the cell. Thus, MnSOD does not always act as a first line mitochondrial antioxidant defense. Recently, a study by our group demonstrated that in the absence of matched upregulation of mechanisms of H2O2 removal, MnSOD overexpression is actually detrimental to the integrity of mitochondria and the maintenance of its energetic functions [28]. This indicates that either directly or indirectly [29,30] MnSOD regulates mitochondrial energetic and signaling functions. Using mitochondria-depleted cancer cells it was established that the abrogation of mitochondria-dependent regulatory functions results in the appearance of highly invasive, aggressive, glycolytic cellular phenotypes [31]. Taken together these observations indicate that progressive MnSOD upregulation, which results in mitochondrial dysfunction, could participate in the appearance of malignant cellular phenotypes characterized by glycolytic metabolism.

In this report, results are presented showing that mitochondrial MnSOD upregulation leads to the activation of AMPK, a cellular metabolic master switch [32,33] that directly enhances glycolysis. We also establish that in cancer cells, mtH2O2 released from mitochondria consequentially to MnSOD upregulation is the signal that engages AMPK to produce and sustain the Warburg effect, thereby enabling cancer cell survival.

RESULTS

MnSOD upregulated in cancer cells promotes glycolysis

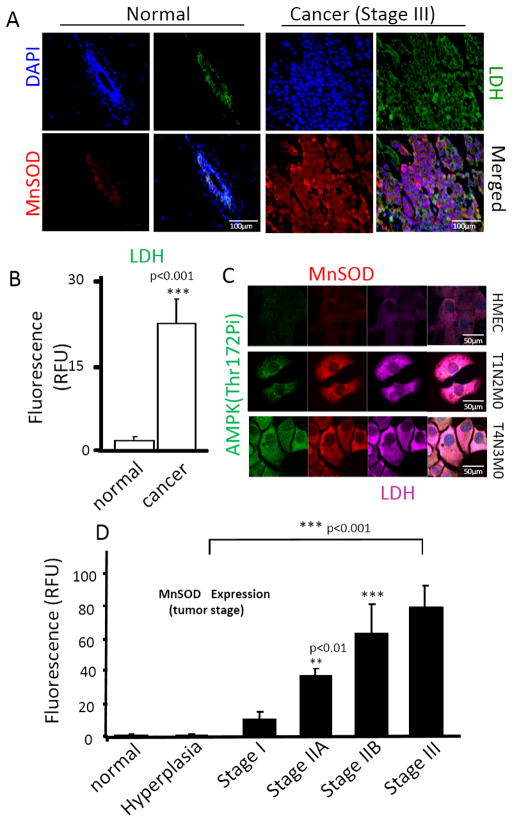

In luminal breast cancer samples stratified by stage, MnSOD expression was present at significantly elevated levels in progressing tumor stages (Figure 1A–D). The levels of MnSOD increased with histologic tumor grade being highest at histologic grade III and lowest in healthy and hyperplastic benign tissue (Figure1D). Elevated MnSOD levels were also observed in advanced prostate (Supplementary Fig. 1A) and colon (Supplementary Fig. 1B) cancer tissue as compared to healthy tissue samples. In breast cancer, MnSOD levels were noted to be highest in triple negative and Her2 subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 2A), elevated in luminal cancers and lowest in healthy control tissue, indicating an association between high MnSOD expression and tumor aggressiveness. This association was further strengthened by the epidemiologic analysis of published data [34] on 5-year breast cancer survival which negatively correlatedwith levels of MnSOD expression. Supplementary Fig. 2B, shows the Kaplan-Meier distribution of 5-year breast cancer survival indicating a clear inverse relationship between survival and MnSOD levels. In all cancer types analyzed (breast, prostate and colon), MnSOD expression was also correlated with expression of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, Figure1B; Supplementary Fig. 1), a surrogate of glycolytic metabolism [35,36] that is associated with poor prognosis. Quantification of total cell MnSOD and LDH fluorescence in breast (Figure 1B), prostate and colon tissue (Supplementary Fig. 1C and 1D, respectively) indicated these changes are significant and support a role for MnSOD upregulation in the switch to glycolysis, a common feature of aggressive cancer subtypes.

Figure 1. Upregulation of MnSOD and the glycolysis surrogate lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in human cancer tissue.

(A) Representative immunostaining of MnSOD and LDH in normal vs cancer tissue. Normal tissue samples were obtained from breast reduction plastic surgery and represent examples of “true healthy” tissue. Cancer tissue is a representative example of Stage III breast cancer collected, graded, processed and stored by the University of Illinois at Chicago tissue bank. Images are representative of over 6 independent cases of each kind. (B) Quantification of LDH expression in breast cancer (Stage III) as a surrogate of glycolytic metabolism. Quantification of corrected total fluorescence of LDH in all tissue samples was performed using ImageJ (imagej.nih.gov), and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad InStat (GraphPad Software). (C) Immunostaining of MnSOD, LDH and phospho-AMPK (Thr172) in primary mammary epithelial cells (HMEC), cells derived from Her/Neu (-) p53 (+) ductal carcinoma (T1N0M0) and invasive ductal carcinoma Her/Neu(-) p53(+) (T4N2M0). Analysis of MnSOD and LDH was performed using confocal microscopy. Images are representative of 15 different fields taken from 3 independent samples (5 fields per dish). (D) Quantification of MnSOD in tissue microarrays containing normal and various cases of breast cancer at different pathologic stages (Protein Biotechnologies). Quantification of corrected total fluorescence of MnSOD was performed using ImageJ and statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (GraphPad InStat). **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. For quantification of protein expression levels in patient samples (shown in B and D) a minimum of 15 independent cases were analyzed.

To assess whether MnSOD upregulation occurs during the progression towards malignancy, MCF10A (non tumorigenic mammary epithelial cells) expressing oncogenic v-Src kinase under the control of an inducible estrogen receptor promoter were used. Activation of v-Src expression by exposure of MCF10-Er-Src cells to tamoxifen resulted in MnSOD upregulation early during the process of malignant transformation (12h, Supplementary Fig. 3) and progressively increased. Fully transformed cells (48–72 h) [37,38] expressed the highest levels of MnSOD. The increase in MnSOD levels during transformation paralleled a strong metabolic shift towards glycolysis with notable reduction in the steady state levels of ATP (Supplementary Fig. 3).

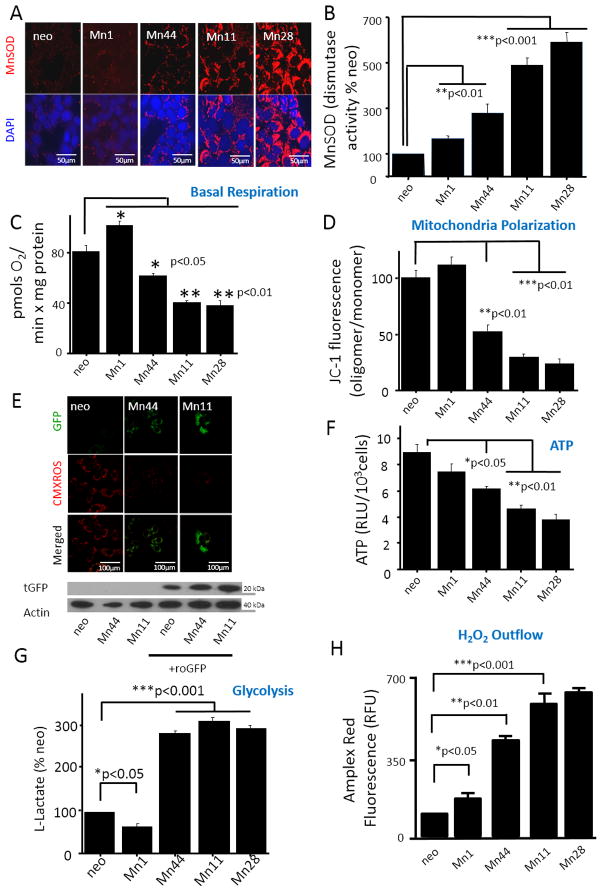

To begin to assess the impact of MnSOD upregulation on breast cancer cells metabolism, 5 isogenic cell lines stably overexpressing MnSOD were obtained. The control cell line expressing the empty vector (neo) and four additional clonal lines Mn1, Mn44, Mn11 and Mn28 expressing MnSOD at various levels (Figure 2A) within the range observed in human breast cancer (Figure 1D) were used to assess the impact of MnSOD expression on O2-dependent metabolism and glycolysis. In accordance with recent observations [39], MnSOD activity increased with enhanced expression levels but not in a directly proportional fashion (Figure 2B). However, incremental increase in MnSOD dampened O2 uptake (Figure 2C) in parallel to dissipating the mitochondrial electrochemical potential as assessed by JC-1 (Figure 2D) and CMXROS (Figure 2E). Importantly, only when MnSOD levels were higher than 5–6 fold over basal (such as in the Mn44 clone) the electrochemical potential dropped in parallel with the reduction in the steady state levels of ATP (Figure 2F) and strong activation of compensatory glycolysis as assessed by lactate production (Figure 2G). Importantly, the elevated MnSOD expression levels were associated to progressive enhancement of H2O2 production (Figure 2H) indicating a redirection in oxygen utilization from ATP production to H2O2 synthesis. Collectively, the findings summarized in Figure 2 support the hypothesis that enhanced MnSOD expression sustains the metabolic switch in cancer cells. Further experiments using the H2O2 biosensor, roGFP targeted to mitochondria, indicated that H2O2 is locally generated in the organelle and that the increase in H2O2, as expected, paralleled the loss of mitochondrial electrochemical potential (Figure 2H).

Figure 2. MnSOD overexpression decreases mitochondrial metabolism and increases mitochondrial H2O2 outflow.

(A) MnSOD-overexpressing epithelial breast cancer lines established in the MCF7 background were analyzed by confocal microscopy for MnSOD expression levels. Representative images of 15 different fields were taken from 3 independent samples (5 fields per dish) (B) Superoxide dismutase activity measured in immunoprecipitated-MnSOD from neo and the MnSOD overexpressing cells. Activity was measured in competition assays with cytochrome c-Fe(III) and xanthine oxidase/hypoxanthine as the source of superoxide (N = 3) (C) O2 uptake measured by Seahorse in cells expressing incremental levels of MnSOD. MnSOD upregulation resulted in decreased basal respiration. Experiments were performed in triplicate (D) Steady state levels of ATP (measured with luciferin/luciferase) in cells expressing incremental levels of MnSOD. (E) Determination of the population of polarized/depolarized mitochondria using JC-1. For the analysis of polarized/depolarized mitochondria, confocal microscopy of live cells incubated with JC-1 (5μM, 20 minutes). Excess JC-1 was removed by washing the cells with PBS prior to analysis. Confocal microscope was set to read red and green channels simultaneously to avoid laser-induced photobleaching. (F) MnSOD overexpression resulted in increased glycolysis (assessed by lactate production rate) using the glycolysis cell-based assay kit (Cayman Chemical) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were counted in the end of the experiments. Lactate production was normalized to cell number. (G) Overexpression of MnSOD resulted in increased output of H2O2, as measured by fluorescence from cells kept in culture using Amplex Red. Amplex Red was dissolved in DMSO and used at a final concentration of 5 μM in phenol red free media containing horseradish peroxidase (0.1 U/ml). (H) Cells transfected with roGFP were treated with CMX-ROS (1 μM), an indicator of mitochondrial potential in phenol red free media, CMXROS accumulation in mitochondria was simultaneously assessed together with roGFP fluorescence by confocal microscopy of live cells. CMXROS was incubated with cells for 5 minutes prior to analysis. Overexpression of MnSOD correlated with an increase in oxidized roGFP (green) and a decrease in mitochondrial potential (red). Quantification of roGFP transfection efficiency by Western blot is shown in (H). For all the experiments above, n=6 unless otherwise noted, * p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.005. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA (GraphPad InStat)

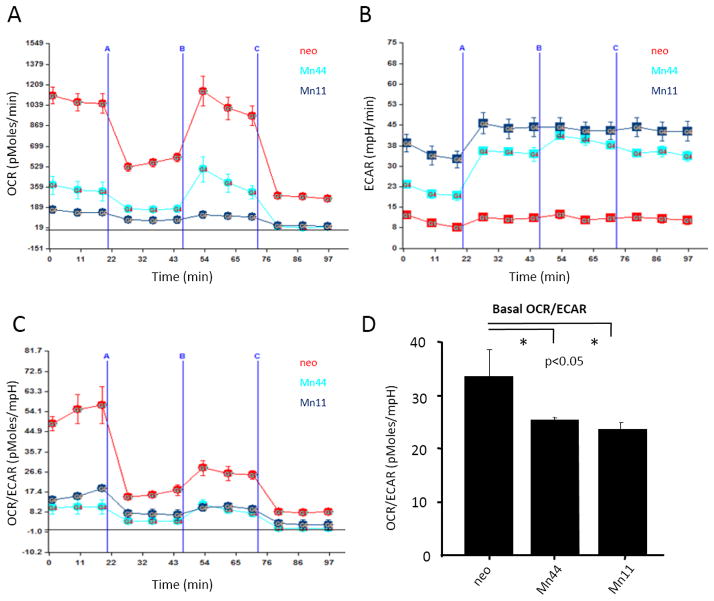

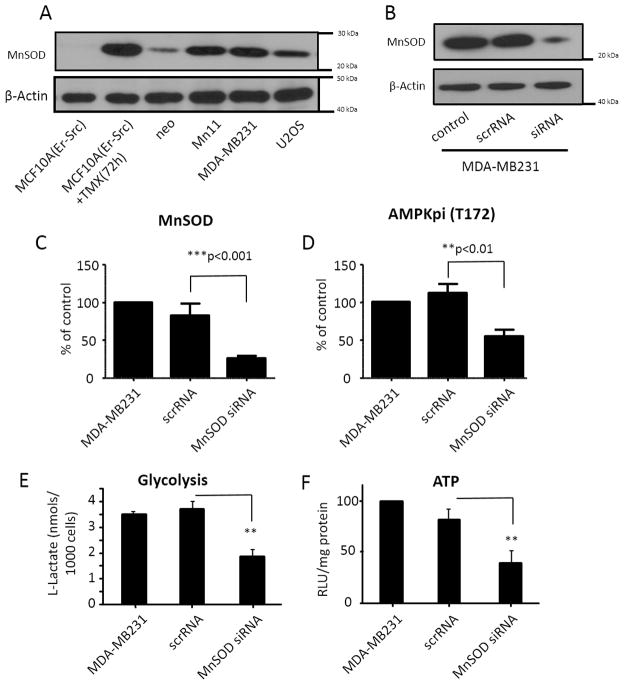

Using extracellular flow analysis (Seahorse Biosciences), we further examined the effect of MnSOD expression on mitochondrial respiration and the glycolytic rate. In agreement with the data shown in Figure 2, cells expressing MnSOD at basal levels (neo) had significantly higher antimycin-inhibitable oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in comparison to Mn44 (moderate MnSOD expression) and Mn11 (high MnSOD expression Figure 3A). Reserve respiratory capacity (the difference between maximal and basal respiratory rates) in all three cell lines was found to be significantly compromised indicating that in all cases mitochondria were functioning at the limit of their respiratory capacity even at baseline MnSOD activity in neo cells. Further confirmation of the increasing dependence of cells expressing high MnSOD levels on glycolysis was obtained in experiments where the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) was measured (Figure 3B). ECAR is a direct measure of lactic acid production by cells and thus of glycolytic activity. As shown in Figure 3C, the OCR/ECAR values for neo cells indicate that these cells are predominantly utilizing mitochondrial metabolism for energy. Higher levels of MnSOD expression in Mn44 and Mn11 promoted an increasing in glycolysis (Figure 3D). The relevance of this finding was highlighted by the observation that in the metastatic and heavily glycolytic breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231), MnSOD expression levels were higher than those found in neo (MCF7 background) (Figure 4A). In comparison to MCF7/neo, glycolytic and metastatic cells (MDA-MB231/U2OS) had MnSOD expression that matched those obtained in the Mn11 clone. Silencing MnSOD in MDA-MB231 cells (Figure 4B) reduced the glycolytic rate of these cells with a parallel decrease in ATP steady state levels (Figure 4E and 4F) indicating that MnSOD-driven glycolysis significantly contributes to the maintenance of ATP production in phenotypically aggressive breast cancer cells.

Figure 3. MnSOD overexpression induces the glycolytic switch in MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

Alterations in cellular metabolism were examined using Seahorse Bioscience XF Analyzer. Cells were plated as a monolayer in the Seahorse plate and left undisturbed until confluent (A) Oxygen consumption rate (OCR), an indication of OXPHOS and (B) extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), an indication of glycolysis, were measured. Mn 44 and Mn 11 cells expressing higher MnSOD levels had decreased OCR and increased ECAR compared to neo cells, (C) OCR/ECAR ratio was calculated and indicated that MnSOD overexpression produces cellular adaptation towards glycolytic metabolism. (D) Overall basal mitochondrial respiration was decreased in Mn44 and Mn11 vs neo as indicated by the ratio OCR/ECAR. Experiments are an average of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc t-test (GraphPad InStat). * p<0.05, (N = 6).

Figure 4. Comparative MnSOD expression and effects in non tumorigenic (MCF10A), tumorigenic (MCF7) and metastatic (MDA-MB-231 and U2OS) cells.

(A) Western blot analysis of MnSOD expression levels in non tumorigenic (non-induced MCF10AErSrc), tumorigenic (TMX-treated MCF10A-Er-Src, MCF7) and metastatic (MDA-MB-231 and U2OS) cell lines. (B) Levels of MnSOD in MDA-MB231 cells manipulated with MnSOD targeted siRNA and respective diminishment in AMPK phosphorylation levels as analyzed by Western blot. (C) Quantification of MnSOD expression by Western blot before and after treatment of MDA-MB231 cells with silencing RNA. (D) Quantification of AMPK phosphorylation before and after MnSOD silencing in MDA-MB231. (E) Effect of MnSOD silencing on the glycolytic rate of MDA-MB-231 cells measured by extracellular flow analysis using Seahorse Biosciences XF analyser. (F) Effect of MnSOD silencing on steady state ATP levels of MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were harvested and analysis was performed 72h after the delivery of siRNA. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc t-test (GraphPad InStat) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; for B, C, D and E statistical analysis was performed using at least 4 independent replicates. Quantification and statistical analysis of G used at least 15 cases classified according to clinical stage and histologic grade.

MnSOD upregulation activates AMP-activated kinase

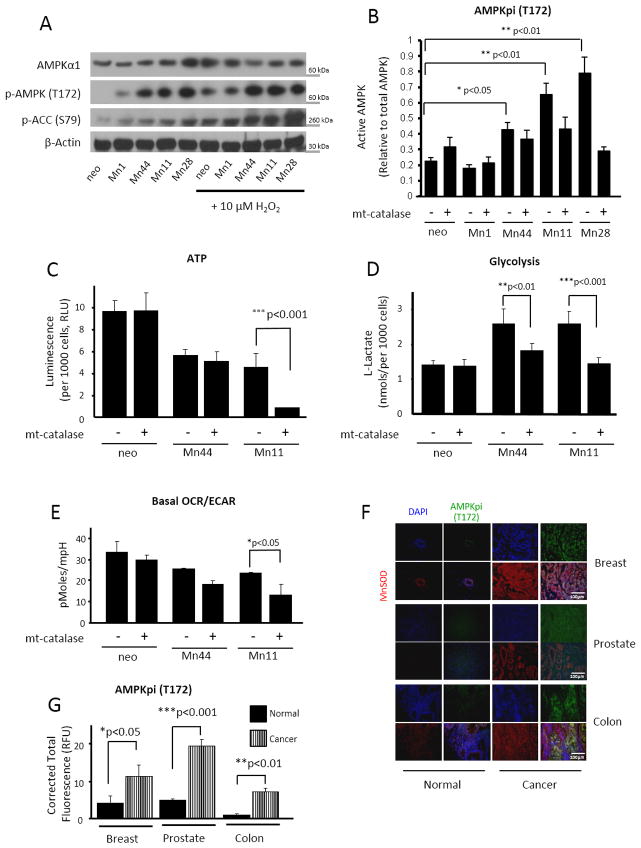

AMPK is a key energetic sensor and regulator of cellular metabolism that is activated by either a reduction in the intracellular ratio ATP/AMP or by the elevation of intracellular H2O2 levels [40]. Because both a reduction in ATP and elevation of H2O2 were found to occur in parallel with MnSOD overexpression, we examined whether AMPK was activated in cells expressing incremental levels of MnSOD. Figure 5A shows that increasing levels of MnSOD expression increased AMPK activity as assessed both by the phosphorylation of active site Thr172 and the phosphorylation of the downstream target Acetyl CoA Carboxylase (ACC). Challenging the cells with exogenous H2O2, the product of MnSOD activity, significantly increased the phosphorylation and activity of AMPK in neo and Mn1 cells (Figure 5A). Conversely, H2O2 only minimally increased AMPK phosphorylation and activity in Mn44 cells and did not further augment the phosphorylation or activity of AMPK in cells expressing high MnSOD levels (Mn11 and Mn28, Figure 5A). These results indicated that the increase in MnSOD expression beyond levels found in Mn44 cells maximally activated AMPK by endogenously generating sufficiently high steady fluxes of H2O2 (Figure 5A). We also confirmed that mtH2O2 was the molecular agent generated by MnSOD that led to AMPK activation. Neo cells were exposed to (0–20 μM) H2O2, and AMPK phosphorylation, the phosphorylation of its downstream target ACC and the intracellular steady state levels of ATP were assessed in side by side experiments (Supplementary Fig. 4). Low H2O2 levels insufficient to cause changes in ATP fully activated AMPK, indicating that H2O2 can produce AMPK activation independently of variations in ATP levels. To further demonstrate that when MnSOD activity is elevated mtH2O2 mediates the activation of AMPK we expressed mitochondria-targeted catalase (mt-catalase) that efficiently dismutates H2O2 into O2 and H2O in mitochondria. Restricting mtH2O2 outflow resulted in a marked decrease in AMPK activation, especially in cells expressing higher levels of MnSOD (Figure 5B). In accordance with our prediction that high MnSOD expression levels lead to a predominantly glycolytic metabolism (in order to maintain ATP production), mt-catalase did not change steady state concentrations of ATP in neo cells but significantly reduced ATP levels by an additional ~ 75% in Mn11 cells (Figure 5C). Addition of mt-catalase also resulted in decreased glycolysis as assessed using lactate accumulation and the overall decrease in basal OCR/ECAR measured by extracellular flow analysis (Figure 5D and 5E). Importantly, the increase in AMPK activity observed in the cells expressing high levels of MnSOD was also observed in breast, colon and prostate cancers (Figure 5F and 5G). Importantly, AMPK activation paralleled MnSOD upregulation during the course of MCF10-Er-Src transformation (Supplementary Fig. 3C), was enhanced in MDA-MB-231 in comparison to MCF7/neo (Figure 4) and was suppressed following silencing of MnSOD in MDA-MB-231 (Figure 4D). Together, these findings provide evidence for the involvement of MnSOD in promoting the glycolytic switch of aggressive breast cancer cells in an AMPK-dependent manner.

Figure 5. AMPK activation is required for the MnSOD-driven glycolytic shift.

(A) Western blot analysis of AMPK activation. Active AMPK was examined using phospho-AMPKα1 (Thr172) and phospho-ACC (Ser 79) as surrogates. Treatment of cells with exogenous H2O2 (5 μM) for 30 minutes significantly increased AMPK activation in neo, Mn1 and Mn44 but did not further enhanced AMPK activity in Mn11 and Mn28. (B) Transfection of mito-catalase into neo and MnSOD overexpressing cells reduced AMPK activation in Mn11 and Mn28 indicating that H2O2 originating from mitochondria activates AMPK. Mito-catalase gene was delivered to MCF7 cells using a lentiviral construct 72h prior to harvesting (C) Treatment with mito-catalase reduced steady state levels of ATP in Mn11 indicating that cells expressing high MnSOD levels depend on mtH2O2 and AMPK activation to support ATP production. Steady state ATP levels were assessed by a chemiluminescence employing luciferin/luciferase mixtures (D) Diminished lactate production by mito-catalase in Mn44 and Mn11 further indicated that MnSOD overexpression via mtH2O2 enhances glycolysis which in turn sustains ATP production. (E) Mito-catalase did not affect the OCR/ECAR ratio in neo cells but significantly altered OCR/ECAR in Mn44 and Mn11 indicating that that MnSOD overexpression leads to the metabolic shift to glycolysis via increasing mtH2O2 outflow. (F) Staining of phospho-AMPKα1 (Thr172) in cancerous human breast, prostate and colon tissue compared to control normal tissue. AMPK phosphorylation (green staining) paralleled an increase in MnSOD expression (red staining). Tissues were collected, processed, graded and stored by the University of Illinois tissue bank (G) Quantification of phospho-AMPKα1 (Thr172) and MnSOD fluorescence staining performed using ImageJ and statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA (GraphPad InStat). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

In view of recent reports implicating AMPK in the maintenance of NADPH levels in cancer cells, we also examined whether the MnSOD-directed activation of AMPK maintained steady state NADPH levels in MnSOD overexpressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 5). The levels of NADPH did not significantly change in cells overexpressing MnSOD when grown in complete media. However, in the absence of glucose, NADPH levels were diminished in MnSOD overexpressing cells consistent with the high demand for NADPH in these cells that may have been sustained by the chronically elevated levels of H2O2 production. These results also indicate that MnSOD, in a glucose-dependent manner, contributes to activate NADPH synthesis possibly via AMPK (Supplementary Fig. 5), thereby sustaining cancer cell biosynthetic capacity, viability and proliferation. AMPK phosphorylation and activity (as assessed by ACC phosphorylation) were found to parallel MnSOD expression in a tumor-stage dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 6). AMPK activity was also found to be significantly increased in early malignant breast tumors as compared to control tissue and to increase progressively with tumor stage (Supplementary Fig. 6). Also, in aggressive breast cancer subtypes, the elevation of MnSOD expression was strongly correlated with an increase in AMPK activation (Supplementary Fig. 6). This observation taken together with findings shown in Figure 5F and G (that AMPK activation also parallels MnSOD upregulation in prostate and colon cancer) indicates the potential relevance of this finding as a mechanism to sustain aggressive cancer cell metabolism in multiple types of cancer.

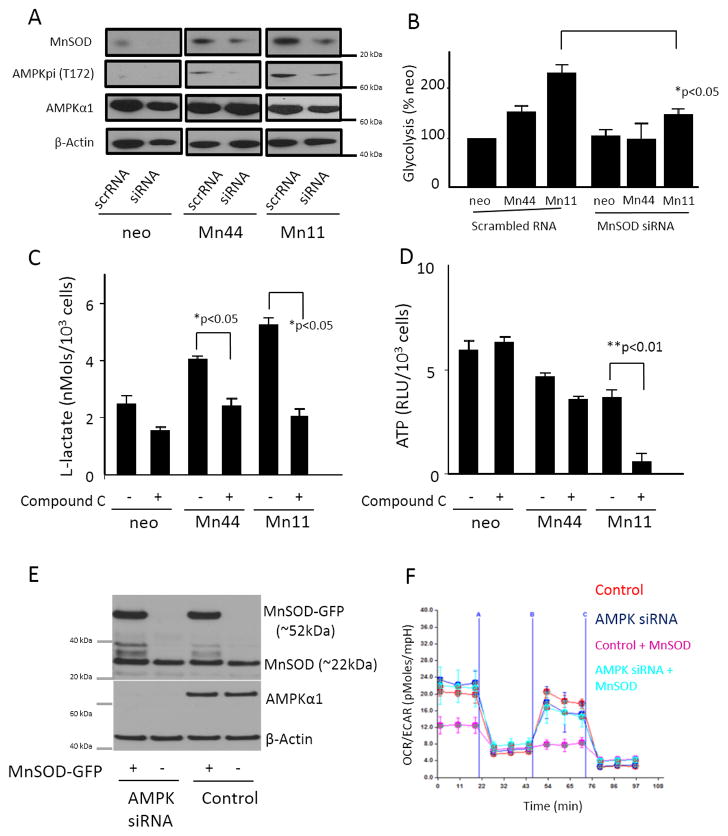

MnSOD/AMPK direct the metabolic shift towards glycolysis

The activating effect of MnSOD upregulation on AMPK and the subsequent shift from cellular oxidative respiration to glycolysis was confirmed by silencing of MnSOD expression in MCF7/neo, Mn44 and Mn11 using siRNA. Suppression of MnSOD expression in Mn44 and Mn11 was controlled to match levels of MnSOD expression equivalent to those found in resting MCF7/neo cells (Figure 6A). AMPK phosphorylation analyzed by Western blot was observed to be reduced in Mn44 and in Mn11 cells transfected with MnSOD siRNA. Silencing of MnSOD caused significant suppression of glycolysis in Mn44 and Mn11 (Figure 6B) while not significantly affecting MCF7/neo. Directly interfering with AMPK using a pharmacologic inhibitor (Compound C) significantly inhibited glycolysis in MCF7/neo, Mn44 and Mn11 cells as expected based on the prominent role of AMPK in activating glycolysis, but only affected ATP levels in Mn44 (mildly, ~ − 30%) and Mn11 (heavily ~ − 85%), Figure 6D. Thus, while neo cells were capable of using different routes for ATP synthesis, cells expressing higher levels of MnSOD appeared to have increasing dependence on glycolysis. This finding was further examined in cells devoid of AMPK’s catalytic subunit AMPKα1. To investigate the effect of MnSOD/AMPK in the induction of the Warburg effect, MnSOD was transfected into MCF-7 cells constitutively expressing AMPKα1 siRNA vs. scrRNA. Results shown in Figure 6E and Figure 6F show that MnSOD overexpression in AMPK-competent cells recapitulated the strong repression of O2 uptake observed in Mn11 cells in parallel with an increase in the extracellular acidification rate (an index of increased glycolytic metabolism). Conversely, overexpression of MnSOD in cells devoid of AMPKα1 produced only marginal effects on cellular metabolism that remained predominantly aerobic.

Figure 6. Suppression of MnSOD or inhibition of AMPK impair the shift to glycolysis in cells overexpressing MnSOD.

MnSOD siRNA was introduced into cells overexpressing MnSOD by electroporation. Cells were harvested 48 h after siRNA delivery. (A) Western blot of protein lysates showed the decrease of MnSOD expression in Mn44 and Mn11 to levels compared to undisturbed neo. The partial downregulation of MnSOD in Mn44 and Mn11 corresponded to a decrease in activated AMPK (Thr172p) analyzed by Western blot. (B) MnSOD siRNA transfection resulted in decreased glycolytic rate compared to untreated cells. The glycolytic rate was assessed by monitoring lactate production between 48 and 52 h post MnSOD silencing. (C) AMPK inhibition with compound C (for 24 h, 25 μM) decreased glycolysis. (D) ATP steady state levels were slightly and markedly decreased in Mn44 and Mn11, respectively by the inhibition of AMPK with compound C. (E) Cells constitutively expressing AMPKα1 siRNA were transfected with MnSOD-GFP or GFP carrying constructs using lipofectamine. Western blot analysis of MnSOD expression levels was performed by Western blot 48h after transfection. (F) Cells overexpressing MnSOD on an AMPK- competent and AMPK-depleted background were analyzed by extracellular flow analysis (seahorse). MnSOD overexpression led to the metabolic shift to glycolysis only when expressed in AMPK-competent cells. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; N = 3 independent replicates.

The dependence of MnSOD overexpressing cells on glucose was also exemplified by the finding that Mn44 and Mn11 could only maintain steady levels of NADPH in glucose rich medium (supplementary Fig. 5) consistent with the expectation that higher intracellular H2O2 leads to accelerated NADPH turnover. These observations are in agreement with recent published work demonstrating that one of the many important functions of AMPK activation in cancer is to maintain NADPH recycling and availability [41] (Supplementary Fig. 5).

MnSOD overexpression upregulates glycolytic enzymes

Additional insight into the importance of the MnSOD/AMPK pathway for the glycolytic shift of cancer cells was obtained by defining whether MnSOD levels affected the expression and activity of key glycolytic enzymes. Hexokinases are enzymes that catalyze glucose phosphorylation for entry in the glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathways and phosphofructokinases (PFK) catalyze the rate limiting step in the glycolytic pathway. Hexokinase and phosphofructokinase activity were found to be enhanced in cells expressing high MnSOD levels in comparison to neo controls. PFK activity was increased consistent with a greater reliance of MnSOD overexpressing cells on glycolysis (Supplementary Fig. 7) and the direct activating effect of AMPK on PFK2. In fact, it was confirmed that MnSOD overexpression in AMPK-competent cells resulted in remarkable phosphorylation of PFK2 on Ser466, an activating AMPK-dependent phosphorylation site [42] (Supplementary Fig. 7B). MnSOD overexpression in AMPK-deficient cells did not result in increased PFK2 phosphorylation supporting our hypothesis that MnSOD sustains the glycolytic activity of cells where it is overexpressed by engaging AMPK-dependent signaling (Supplementary Fig. 7). Notably, a marked reduction in the expression levels of mitochondrial electron transfer chain complexes II, III, IV and V (Supplementary Fig. 8A) was observed in cells overexpressing MnSOD consistent with the observations of reduced mitochondrial potential and O2 uptake. In parallel, we analyzed the expression of key antioxidant enzymes in order to gain additional understanding of the mechanisms underlying the persistent elevation in H2O2 due to MnSOD upregulation. Catalase, glutathione reductase, thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase were examined and only thioredoxin was significantly reduced in Mn44, Mn11 and Mn28 cells (Supplementary Fig. 8B). These results indicate that alterations in the expression and functioning of electron transfer chain complexes in MnSOD overexpressing cells enhance mtH2O2 production unopposed by the major H2O2 scavenging systems.

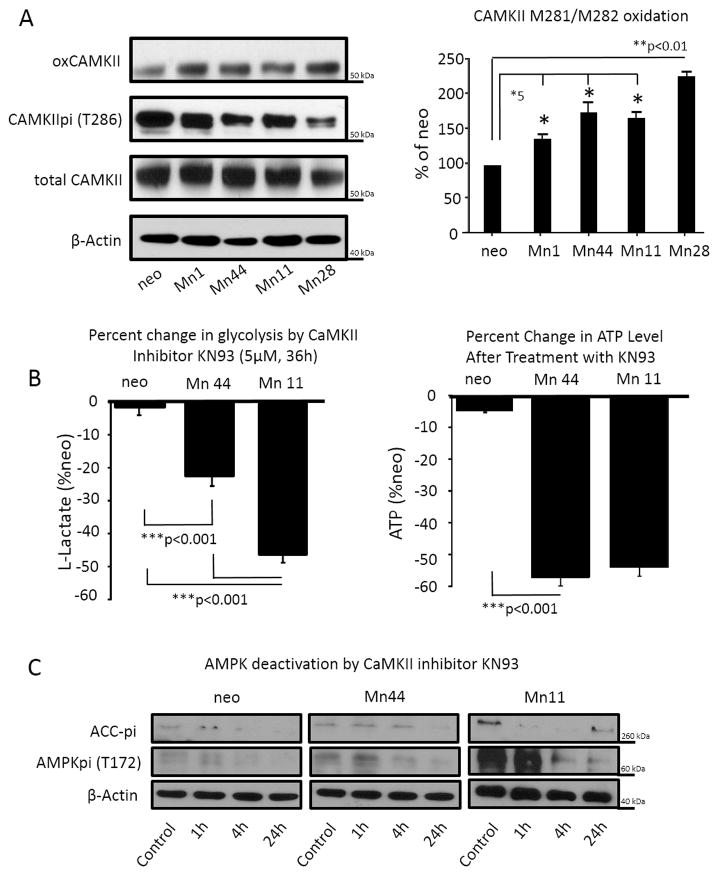

CaMKII, a redox sensitive kinase that activates AMPK

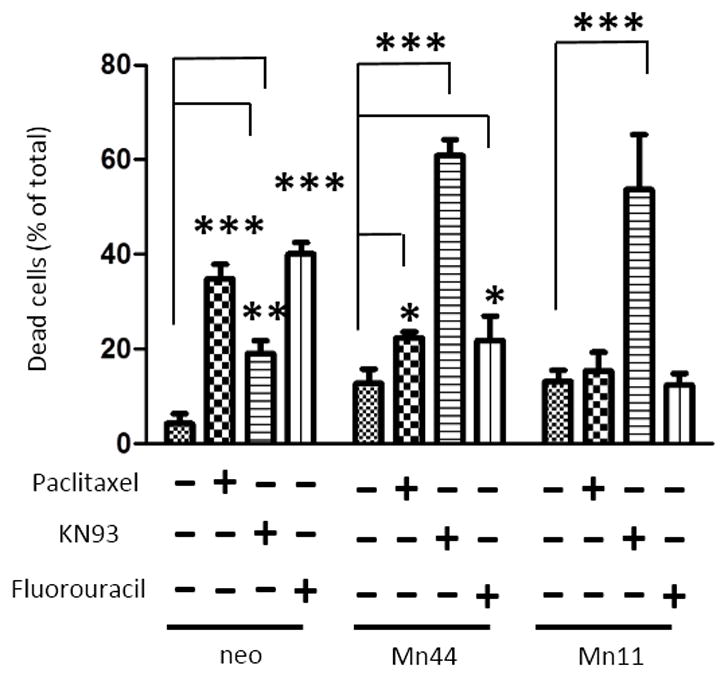

Data presented above indicated that the constitutive elevation of cellular H2O2 maintained AMPK activation thereby promoting the irreversible conversion of the cellular metabolism to glycolytic. The mechanism of MnSOD-dependent AMPK constitutive activation was next investigated with a focus on CaMKII, a kinase responsive to H2O2-driven oxidative activation upstream of AMPK [43,44]. Oxidation of CaMKII at residues M281 and M282 had previously been shown to result in chronic activation, and this constitutive activation of CaMKII was apparent even in cells overexpressing low levels of MnSOD (2 – 3 fold over basal, Mn1), Figure 7A. Consistent with the hypothesis that AMPK is critical for maintaining increased glycolysis and steady state ATP levels in MnSOD overexpressing cells; the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 dampened glycolysis and reduced the steady state ATP levels in Mn44 and Mn11 cells (Figure 7B). Importantly, inhibition of CaMKII resulted in robust dephosphorylation of AMPK at the active site Thr172 (Figure 7C). Decreased AMPK phosphorylation was accompanied, as expected, by a reduction in AMPK activity as indicated by lower levels of phosphorylated ACC (Figure 7C), a downstream target of AMPK. This observation indicates that CaMKII oxidation by mtH2O2 leads to its constitutive activation and consequentially the activation of AMPK. Relevantly, inhibition of CaMKII markedly reduced the viability of cells expressing high MnSOD levels (Figure 8). The potential clinical importance of this finding was furthered by comparing the effect of CaMKII inhibitor KN93 with two commonly used breast cancer chemotherapeutic compounds, paclitaxel (a mitotic inhibitor) and 5-fluorouracil (a thymidylate synthase inhibitor). Exposure to KN93 resulted in 60–70% cell death of Mn44 and Mn11 cells while only minimally reducing the viability of MCF7/neo cells by 20% approximately, which was in clear contrast to the effect of paclitaxel and 5-flurouracil which were far more efficient in killing MCF7/neo (Figure 8). This observation indicated that cells expressing high MnSOD levelsare far more sensitive to CaMKII inhibition than to paclitaxel or 5-fluorouracil.

Figure 7. Calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) is a redox sensitive kinase upstream of AMPK.

(A) CaMKII oxidation was examined by Western blot using an antibody recognizing the oxidation of M281/M282 to methionine sulfoxide on CaMKII. Panel to the right shows quantification by densitometry of oxidized CaMKII detected in three independent experiments. (B) Impact of KN93 (a bona fide CaMKII inhibitor) on lactate production and steady ATP levels in neo, Mn44, Mn11. Water soluble KN93 (5 μM) was diluted into complete media. Cells were harvested at 36 h for assessments of lactate production and steady state levels of ATP as described in methods. (C) The impact of CaMKII inhibition with KN93 on AMPK phosphorylation and activity (pACC was used as a surrogate) was examined. Cells exposed to KN93 (5 μM) were harvested at the indicated time points after KN93 addition to full media, lysed and analyzed for AMPK(Thr172p) and pACC (Ser79) content by Western blot. *p<0.05; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01. Statistical analysis was performed using 6 independent replicates.

Figure 8. Comparative effect of anticancer drugs paclitaxel (5 μM), 5-fluorouracil (2 mM) and the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 (5μM) on cellular viability.

Cells (neo, Mn44 and Mn11) were exposed to the specified compounds as indicated for 48 h in full media. After 48 h cells were harvested and viability was determined by flow cytometry using YOPROTM and propidium iodide as described in methods. Experiments show averages of 6 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (GraphPad InStat) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

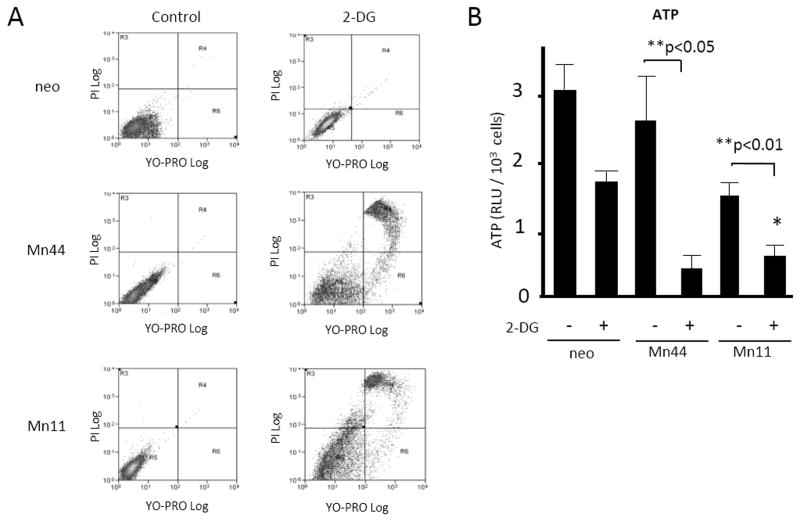

Glycolysis maintains cells overexpressing MnSOD viable

The dependence of cells expressing high MnSOD levels on glycolysis was further examined by conducting experiments where glycolysis was inhibited using 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG). MCF7/neo, Mn44 and Mn11 cells were treated with 2-DG(a potent glucose analog that cannot be metabolized) and then apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry (Figure 9). 2-DG produced marked cell death among Mn11 cells compared to MCF7/neo controls. The inhibition of glycolysis dramatically lowered steady state ATP levels in Mn44 and Mn11 cells, while only moderately inhibiting ATP production in neo cells (Figure 9B). These results indicate that glycolysis significantly contributes toATP production in MCF7/neo cells, but accounts for most, if not all, of the ATP production in cells expressing high MnSOD levels. Accordingly, we found that supplementation of media with substrates that support glycolytic metabolism (pyruvate and uridine) stimulated Mn11 and Mn28 proliferation without affecting MCF7/neo or Mn1 growth rates (Supplementary Fig. 9). The proliferation rate of Mn11 and Mn28 in the presence of pyruvate and uridine was comparable to the baseline proliferation rate of MCF7/neo, dismissing the concept that MnSOD per se is a tumor suppressor. Rather, MnSOD imposes a form of metabolism that requires glycolysis-supportive substrates to maintain rapid cellular proliferation.

Figure 9. Inhibition of glycolysis decreased viability and ATP steady state levels in lines expressing high MnSOD levels.

Cells were treated with the glucose competitor 2-deoxy-glucose (2-DG, 10 mM for 36 h) and analyzed by flow cytometry using YOPROTM, an indicator of apoptosis and propidium iodide, an indicator of cell death. (A) Cells overexpressing MnSOD were more susceptible to 2-DG –induced apoptosis compared to control cells (neo). Mn44 and Mn11 cells as expected were the most vulnerable to glycolysis inhibition. (B) In cells treated with 2-DG, there were also decreases in steady state ATP levels analyzed by chemiluminescence 36 h after 2-DG addition to the media. Reductions in ATP levels were marked in Mn44 and Mn11 confirming the reliance of these cells on glycolysis for ATP production. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (GraphPad InStat) **p<0.01; N = 3 independent experiments.

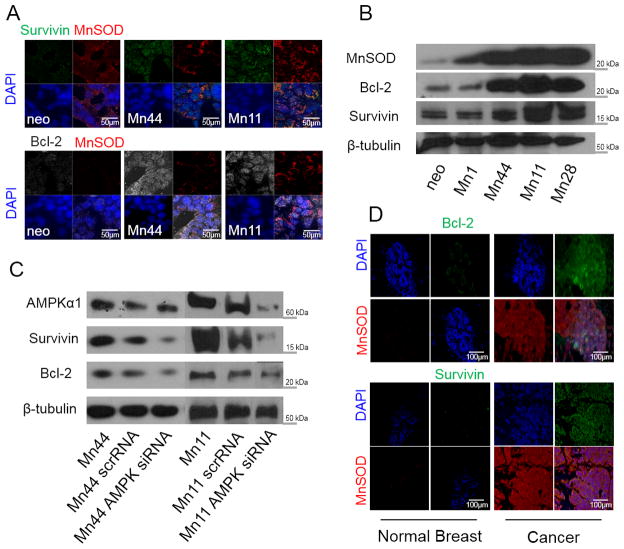

Activation of the MnSOD/AMPK axis suppresses apoptosis

MnSOD is known to promote cell survival and inhibit apoptosis by mechanisms that remain poorly defined [45]. Since AMPK has been implicated in upregulating Bcl-2/survivin expression [46], we examined the possibility that in addition to the metabolic effects describd above, MnSOD/AMPK fostered cancer cell survival by upregulating anti-apoptotic factors such as survivin and Bcl-2. Cells expressing high MnSOD levels also had concurrent increases in survivin and Bcl-2 (Figure 10A and 10B). To test the involvement of AMPK in the induction of survivin and Bcl-2 expression by MnSOD, AMPK expression was reduced using siRNA which resulted in decreased Bcl-2 and survivin levels in both Mn44 and Mn11 cells. This observation implicates AMPK as a critical mediator of MnSOD-induced anti-apoptosis (Figure 10C). Expression of MnSOD and survivin/Bcl-2 were also similarly increased in human cancer tissues compared to control tissue (Figure 9D). Furthermore, KN93 was observed to be a potent inducer of apoptosis of MnSOD overexpressing cells, likely because of additive effects in suppressing AMPK-driven metabolic and anti-apoptotic routes (Figure 8). These findings support a critical role for MnSOD/oxCaMKII/AMPK in the maintenance of glycolytic cancer cell survival while adding mechanistic insight to the known anti-cancer effect of CaMKII inhibition [45,47]. MnSOD upregulation also repressed the cleavage of effector caspases 3 and 7 while activating caspase 9 and downregulating p53 expression (Supplementary Fig. 10). These findings further substantiate the critical role of MnSOD in adaptative responses that favor cancer cell survival. Our studies also indicate that MnSOD upregulation produced phenotypes that metabolically and functionally resemble more malignant cells such as those that occur in late stage and aggressive subtypes of breast cancers. This conclusion was further supported by experiments using MCF10-Er-Src cells where MnSOD upregulation was shown to be essential for the survival of transformed cells (Supplementary Fig. 11). Silencing MnSOD prior to induction of MCF10A-Er-Src transformation induced by tamoxifen led to > 70% cell death 48 h after tamoxifen stimulation. Although MnSOD ectopic expression did not significantly increase metastasis of xenografts produced in NOD/SCID mice, enhanced MnSOD expression in breast cancer cells conferred characteristics of aggressive cancer cells such as glycolytic metabolism (Figure 2 and 3), drug resistance (Figure 8), and enhanced capacity to grow in soft agar (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Figure 10. MnSOD induces the expression of survival proteins in an AMPK-dependent manner.

(A) Survivin and Bcl-2 protein expression in neo, Mn44 and Mn11 cells were measured by confocal microscopy. (B) same as (A) but protein expression was analyzed by Western blot in neo, Mn1, Mn44, Mn11 and Mn28 cells.(C). Silencing of AMPK by siRNA transfection with lipofectamine decreases Bcl-2 and survivin expression in Mn44 and Mn11 (results from the analysis of Mn44 and Mn11 are from different sections of the same nitrocellulose membrane). AMPK siRNA was transfected with lipofectamine 72 h prior to harvesting (D) Immunohistochemical analysis shows increased expression of anti-apoptotic proteins survivin and Bcl-2 in human breast cancer tissues in parallel with increased MnSOD expression. Representative images of at least 15 different cases (Stage III, ductal invasive carcinoma) are shown.

DISCUSSION

Investigations dedicated to unraveling the role of MnSOD in tumorigenesis and cancer progression have yielded conflicting results in regard to the nature and potential effects of MnSOD in influencing cancer risk, prognosis, survival, susceptibility to therapy, and likelihood of relapse. Recently the consideration of MnSOD expression in specific contexts along with the functional status of other cellular antioxidant systems led to the more encompassing idea that MnSOD contributes to the progression of tumors towards aggressive phenotypes in which MnSOD enhances anti-apoptotic defenses and increases invasion [47,48]. The role of MnSOD as a primary participant and director of the malignant transformation process has been less appreciated; however, MnSOD and its product H2O2 have recently been shown to play critical roles in controlling oxygen consumption rates and glucose uptake in mouse embryonic fibroblasts as these cells progress through the cell cycle from quiescence to proliferative states [49] and in a variety of other systems where MnSOD and H2O2 affect survival and cellular function [50–56]. Our results provide direct evidence in support of the concept that MnSOD strongly suppresses mitochondrial oxidative metabolism while bolstering glycolysis by mechanisms that involve the rerouting of O2 towards the production of a steady flow of mtH2O2. MnSOD expression is regulated by inflammatory [57,58], metabolic, and stress activated transcription factors [59–61] and is generally expressed in response to an acute insult [62,63]. While the possibility that MnSOD provides protection against stress when acutely upregulated has been extensively scrutinized [64–66], our results indicate that when persistently overexpressed at levels found in human cancers, MnSOD contributes to the progressive deterioration of mitochondrial bioenergetics and the activation of glycolysis via mtH2O2 production and AMPK activation. Interestingly, a similar role for SOD1, a cytosolic superoxide dismutase has been described [67]. Although through a different mechanism (association with two casein kinase 1-gamma homologs) it was demonstrated that H2O2 generation was required to suppress mitochondrial respiration and stimulate glycolysis indicating, as proposed here, that the manipulation of intracellular levels of H2O2 may be of therapeutic utility in cancer. In fact, according to the results shown in Figures 1–5 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, the persistent upregulation of MnSOD with parallel increase in steady state levels of H2O2 seem to be a distinctive feature of transformed cells that appears to satisfy critical energetic and metabolic necessities. Moreover, we found that repressing signals originating from MnSOD overexpression (such as mtH2O2, oxCaMKII, AMPK) strongly inhibit glycolysis without reactivating oxidative based metabolism in mitochondria. Consequently, the interruption of MnSOD/mtH2O2/oxCaMKII/AMPK signaling results in the metabolic collapse of cells derived from advanced stage cancers (MDA-MB-231 and transformed MCF10A-Er-Src) resulting in marked cell death. Hydrogen peroxide originating in mitochondria (mtH2O2) was identified as the agent that integrates MnSOD-dependent mitochondrial signaling with the activation of AMPKwhich was confirmed in experiments where we attenuated mtH2O2 levels by ectopically expressing mitochondria-targeted catalase which rapidly dismutates H2O2 preventing its long range effects. The effect of mito-catalase in repressing glycolysis in MnSOD-overexpressing cells indicates that there is an aggressive cancer-specific mechanism of glycolysis centered on the mitochondria-driven activation of the MnSOD/AMPK axis. This conclusion is based on the observation that silencing MnSOD or inhibiting AMPK reduces glycolysis to baseline levels while only marginally affecting ATP levels in cells expressing low levels of MnSOD (MCF7/neo cells). Inhibition of glycolysis with 2-DG reduced steady state ATP levels in all cells lines examined but only killed those expressing elevated MnSOD levels such as Mn44 and Mn11 cells. Taken together with the observation that mitochondria-driven ATP production was severely impaired in Mn44 and Mn11 lines, it is proposed that MnSOD promotes survival independently of oxygen (a clinically relevant problem) at the expense of metabolic flexibility. In this regard, the identification of a specific mitochondria-to-AMPK signaling axis that is activated by MnSOD upregulation and dependent on mtH2O2 in cancer cells can potentially be exploited for cancer therapeutic as thisis not likely to interfere with normal glycolytic processes in healthy cells. This is especially important in view of recent findings demonstrating that AMPK activation is critical for the maintenance of cancer cell biosynthetic activity [68].

On investigating the possible mechanisms by which AMPK is maintained constitutively activated in cells overexpressing MnSOD, we identified CaMKII as the redox sensitive kinase activated upstream of AMPK, thereby translating the persistent increase of intracellular H2O2 into constitutive AMPK activation. The critical role of CaMKII in sustaining metabolic alterations required for cancer cell survival was illustrated by the effectiveness of KN93 in inhibiting AMPK phosphorylation and activity, and by its effectiveness in selectively killing MnSOD overexpressing cells as compared to neo control cells. Collectively, these experiments identified a mechanistic basis for the development of KN93 as an anti-cancer agent.

The likely clinical relevance of the data presented herein is further supported by the strong parallels between the results obtained in cell lines where MnSOD expression was manipulated and tissues obtained from patient biopsies where MnSOD, Bcl-2, and survivin were strongly upregulated in parallel with AMPK activation. The finding of elevated Bcl-2 and survivin expression in tumors has been generally associated with poor prognosis; therefore, mechanisms to suppress the expression of these anti-apoptotic proteins in tumors are generally regarded as attractive therapeutic goals. By specifically targeting the MnSOD/mtH2O2/AMPK axis, treatments may be developed to limit the expression of Bcl-2 and survivin thereby diminishing the reliance on existing therapies that eliminate cancer cells but have prominent detrimental off-target effects.

MnSOD upregulation, AMPK activation, and a gradual shift towards glycolysis as described in this work are to be regarded as part of a multifaceted process that occur in carcinogenesis. We see the MnSOD/oxCaMKII/AMPK-dependent metabolic switch in cellular metabolism as a necessary occurrence for the successful establishment of malignancy that, based on the results presented herein, permits cells to survive oxygen deprivation while strongly promoting anti-apoptotic defenses. As alterations in cellular metabolism from mitochondria-based to glycolytic encompasses relevant to almost all malignant solid tumors, we think that these data identify the MnSOD/H2O2/AMPK axis as a primary regulator of the Warburg effect and as such, a valuable new piece to the complex puzzle that is tumor progression.

Methods

Human patient sample analysis

Deidentified human tissue samples were obtained from the University of Illinois at Chicago tissue bank according to IRB exemption note 20110082-58687-1/OPRS/UIC. Multiple images were acquired from at least 6 individual normal and 6 cancerous breast, prostate and colon tissues, as identified by Dr. Andre Kajdacsy-Balla, a clinical pathologist. Representative images were used for Figures 1, 4F, 9 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry

Slides were blocked with regular fetal calf serum and incubated with primary antibody (MnSOD, LDH, diluted 1:1000 in 1X TBST, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), overnight at 4°C. After rinsing in TBST, sections were incubated with Alexafluor conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen/Life Sciences, Grand Island, NY). Slides were examined on a Nikon ECLIPSE E400 microscope and documented using SPOT Advanced version 4.0.1 software.

TMA Analysis

MnSOD expression in multiple molecular subtypes of breast cancer was assessed using immunofluorescent imaging of tissue micro-array TMA-1005 (Protein Biotechnologies, Ramona, CA). Protein was blocked with normal serum and incubated with anti-MnSOD, anti-pAMPK-Thr172 (diluted 1:100 in 1x TBST containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) overnight at 4°C. Slides were then incubated with Alexafluor conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen/Life Sciences, Grand Island, NY) and examined on an Apotome (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Relative fluorescent intensity was measured using ImageJ, and RFU values were associated with molecular subtypes described previously [69].

Quantitation of Relative Fluorescent Units

Corrected total fluorescence was calculated as described previously [70]. Three background samples were taken per selection to assure proper calibration.

Measurement of MnSOD activity

MnSOD was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates using a mouse anti-MnSOD antibody conjugated to protein A-bound resin. 20μg or protein from lysates was loaded into PBS solutions containing 20μg anti-MnSOD antibody. MnSOD activity was calculated compared to MCF7/neo based on the ability of MnSOD-bound to resin to inhibit the reduction of 50 μM cytochrome c Fe(III) reduced by hypoxanthine (50μM)/xanthine oxidase (10 mU/ml) system. Incubations of MnSOD-immobilized to resin, cytochrome c and xanthine oxidase/hypoxanthine were vigorously agitated. Total cytochrome c reduction was measured by absorbance at 550 nm after 30 minutes incubation at room temperature.

Confocal microscopy

Cells were plated onto MatTek glass-bottomed culture dishes and allowed to adhere overnight. After treatments, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA. Cells were permeabilized using cold methanol. Images were recorded using a Zeiss LSM510UV META confocal microscope.

Amplex Red Assay

H2O2 production from cells was measured using the Amplex Red Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit (Invitrogen/Life Sciences, Grand Island, NY).

Mito-Catalase Transfection

Cells were grown in a 6-well plate in media. Mito-catalase adenovirus was added to treatment wells and allowed to infect cells for 24 hours. Virus was a generous gift from Dr. J. Andres Melendez (SUNY, Albany).

ATP Assay

Cells were grown in a white walled, clear bottom 96 well plate in media, transferred to glucose free media with galactose and then analyzed for ATP production using the Mitochondrial Tox-Glo Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) on a spectrophotometer.

JC-1 Assay

Cells were grown in MatTek confocal dishes. On achieving 70% confluency, cells were incubated in 5 μM JC-1 for 20 minutes at 37°C then washed 2X in PBS and immediately imaged by confocal microscopy.

Glycolysis Assay

Cells were grown in a 96 well plate in media, transferred to serum free media for 24 hours, and then analyzed for glycolytic activity using the Glycolysis Cell-Based Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

MnSOD/AMPK silencing

MnSOD, AMPK and scrambled siRNA were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and incorporated into cells via electroporation using Amaxa Nucleofector Technology (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). After electroporation, cells were plated and incubated for 24 hours, then collected for protein analysis by Western blot, or plated for glycolysis measurements.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were analyzed using YOPROTM and propidium iodide for apoptosis and viability by flow cytometry at the University of Illinois at Chicago Research Resources Flow Cytometry Service.

6-phosphofructokinase (PFK), pyruvate kinase (PK) and hexokinase (HK) activity assays

Colorimetric assay kits were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge MA). Enzyme activities were measured following manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, equal amounts (1–2 × 106 cells) of each cell line were lysed with cold assay buffer on ice, and supernatant mixed with freshly prepared reaction mix in 96-well plates. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes, and absorbance was measured every 10 minutes. Two time points (20 min and 60 min) were chosen to calculate the enzyme activity.

Transformation of MCF10A-Er-Src and silencing of MnSOD

For silencing of MnSOD in MCF10A(Er-Src) cells, Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) was used as per manufacturer’s instructions. Silencing was performed using control scrRNA and MnSOD siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Briefly, cells were incubated with either scrRNA or siRNA at 37°C for 8 hours, and then treated with 1 μM tamoxifen (Sigma Aldrich). The cells were harvested for analysis 48 hours after tamoxifen was added. For transformation MCF10A-Er-Src cells were plated at 50% confluency and maintained in 1 μM tamoxifen for the duration of the experiment as indicated. MCF10AEr-Src cells were a kind gift from Dr. Kevin Struhl (Harvard University).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad InStat by using one-way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls comparison. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant whereas values of p<0.01 and p<0.001 were considered highly significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Drs. Larry W. Oberley (in memoriam) and Frederick Domann (University of Iowa) for the generous gift of cell lines stably overexpressing MnSOD, Dr. Kevin P. Claffey (University of Connecticut) for the generous gift of MCF-7-AMPKα1 −/− cells, Dr. Kevin Struhl (Harvard University) for the gift of the MCF10A lines expressing v-Src under ER induction, Patricia Mavrogianis, Andrew Hall, and Emily Ionetz at the Research Histology Core at the University of Illinois at Chicago for providing histology services, Dr. Soumen Bera, Emmanuel Ansong, Paula Green, Alyssa Master and M. Saqib Baig for technical assistance, and for funding provided by the U.S. Department of Defense (ARO #61758-LS) to M.G.B, the NCRR/NIH (S10RR027848) to M.G.B., 1R21CA182103-01 to A.M.D. and M.G.B.. K.A.F. and P.C.H. were supported by NIH T32 (HL072742). The authors also acknowledge gifts from RO1 CA101053 to A.M.D., NIH P01 HL60678 to R.D.M., CAPES – Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento Pessoal, Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia/Brazil – A109/2013 to M.G.B. and M.E.L.C.

Footnotes

Authors contributions:

Key experiments were performed by PCH, KAF, MM, ALA, DNK, DG. PCH, KAF, MM, ALA, DNK, AMD, JHS, MGB conceived and designed experiments. Data interpretation and hypothesis were generated by PCH, KAF, MM, AMD, AKB, RDM, MELC, JHS, MGB. DNK, AKB, AMD provided exclusive reagents and model systems. AKB built, classified and analyzed data from TMA. AMD, RDM, JHS, MELC and MGB – wrote the manuscript. MGB had the general oversight of the project.

Competing Financial Interests: None to disclose

References

- 1.Bell EL, Klimova T, Chandel NS. Targeting the mitochondria for cancer therapy: regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor by mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:635–640. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullen AR, Wheaton WW, Jin ES, Chen PH, Sullivan LB, et al. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature. 2012;481:385–388. doi: 10.1038/nature10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo DK, Green PD, Santos JH, D’Souza AD, Walther Z, et al. Mitochondrial genome instability and ROS enhance intestinal tumorigenesis in APC(Min/+) mice. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tormos KV, Anso E, Hamanaka RB, Eisenbart J, Joseph J, et al. Mitochondrial complex III ROS regulate adipocyte differentiation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehman J, Zhang HJ, Toth PT, Zhang Y, Marsboom G, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission prevents cell cycle progression in lung cancer. FASEB J. 2012;26:2175–2186. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-196543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majewski N, Nogueira V, Bhaskar P, Coy PE, Skeen JE, et al. Hexokinase-mitochondria interaction mediated by Akt is required to inhibit apoptosis in the presence or absence of Bax and Bak. Mol Cell. 2004;16:819–830. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunelle JK, Santore MT, Budinger GR, Tang Y, Barrett TA, et al. c-Myc sensitization to oxygen deprivation-induced cell death is dependent on Bax/Bak, but is independent of p53 and hypoxia-inducible factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4305–4312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon H, Madar S, Rotter V. Mutant p53 gain of function is interwoven into the hallmarks of cancer. J Pathol. 2011;225:475–478. doi: 10.1002/path.2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim YCY, Roberts TL, Day BW, Harding A, Kozlov S, et al. A role for homologous recombination and abnormal cell cycle progression in radioresistance of glioma initiating cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly PN, Strasser A. The role of Bcl-2 and its pro-survival relatives in tumourigenesis and cancer therapy. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1414–1424. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDuff FK, Turner SD. Jailbreak: oncogene-induced senescence and its evasion. Cell Signal. 2011;23:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryson JM, Coy PE, Gottlob K, Hay N, Robey RB. Increased hexokinase activity, of either ectopic or endogenous origin, protects renal epithelial cells against acute oxidant-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11392–11400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamanaka RB, Chandel NS. Targeting glucose metabolism for cancer therapy. J Exp Med. 2012;209:211–215. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wheaton WW, Chandel NS. Hypoxia. 2. Hypoxia regulates cellular metabolism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C385–393. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00485.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glick D, Zhang W, Beaton M, Marsboom G, Gruber M, et al. BNip3 regulates mitochondrial function and lipid metabolism in the liver. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2570–2584. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00167-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordan JD, Thompson CB, Simon MC. HIF and c-Myc: sibling rivals for control of cancer cell metabolism and proliferation. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robey RB, Hay N. Is Akt the “Warburg kinase”?-Akt-energy metabolism interactions and oncogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marin-Valencia I, Yang C, Mashimo T, Cho S, Baek H, et al. Analysis of tumor metabolism reveals mitochondrial glucose oxidation in genetically diverse human glioblastomas in the mouse brain in vivo. Cell Metab. 2012;15:827–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Q, Chen X, Ma J, Peng H, Wang F, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin up-regulation of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme type M2 is critical for aerobic glycolysis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4129–4134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014769108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sgambato A, Camerini A, Collecchi P, Graziani C, Bevilacqua G, et al. Cyclin E correlates with manganese superoxide dismutase expression and predicts survival in early breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant epirubicin-based chemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1026–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ennen M, Minig V, Grandemange S, Touche N, Merlin JL, et al. Regulation of the high basal expression of the manganese superoxide dismutase gene in aggressive breast cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1771–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quiros I, Sainz RM, Hevia D, Garcia-Suarez O, Astudillo A, et al. Upregulation of manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) is a common pathway for neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1497–1504. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weaver ZA, McCormack SJ, Liyanage M, du Manoir S, Coleman A, et al. A recurring pattern of chromosomal aberrations in mammary gland tumors of MMTV-cmyc transgenic mice. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25:251–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhar SK, Tangpong J, Chaiswing L, Oberley TD, St Clair DK. Manganese superoxide dismutase is a p53-regulated gene that switches cancers between early and advanced stages. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6684–6695. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ansenberger-Fricano K, Silva Ganini DD, Mao M, Chatterjee S, Dallas S, et al. The peroxidase activity of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holley AK, Dhar SK, St Clair DK. Manganese superoxide dismutase versus p53: the mitochondrial center. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1201:72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holley AK, Dhar SK, St Clair DK. Manganese superoxide dismutase vs. p53: regulation of mitochondrial ROS. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kulawiec M, Safina A, Desouki MM, Still I, Matsui S, et al. Tumorigenic transformation of human breast epithelial cells induced by mitochondrial DNA depletion. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1732–1743. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.11.6729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winder WW, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase, a metabolic master switch: possible roles in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E1–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.1.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu M, Neilson A, Swift AL, Moran R, Tamagnine J, et al. Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C125–136. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kao KJ, Chang KM, Hsu HC, Huang AT. Correlation of microarray-based breast cancer molecular subtypes and clinical outcomes: implications for treatment optimization. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qing G, Skuli N, Mayes PA, Pawel B, Martinez D, et al. Combinatorial regulation of neuroblastoma tumor progression by N-Myc and hypoxia inducible factor HIF-1alpha. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10351–10361. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawson DM, Goodfriend TL, Kaplan NO. Lactic Dehydrogenases: Functions of the Two Types Rates of Synthesis of the Two Major Forms Can Be Correlated with Metabolic Differentiation. Science. 1964;143:929–933. doi: 10.1126/science.143.3609.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Struhl K. Metformin inhibits the inflammatory response associated with cellular transformation and cancer stem cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:972–977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221055110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Wang G, Struhl K. Inducible formation of breast cancer stem cells and their dynamic equilibrium with non-stem cancer cells via IL6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1397–1402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaiswing L, Zhong W, Oberley TD. Increasing discordant antioxidant protein levels and enzymatic activities contribute to increasing redox imbalance observed during human prostate cancer progression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;67:342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M, Dong Y, Xu J, Xie Z, Wu Y, et al. Thromboxane receptor activates the AMP-activated protein kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells via hydrogen peroxide. Circ Res. 2008;102:328–337. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.163253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon SM, Chandel NS, Hay N. AMPK regulates NADPH homeostasis to promote tumour cell survival during energy stress. Nature. 2012;485:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature11066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsin AS, Bertrand L, Rider MH, Deprez J, Beauloye C, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of heart PFK-2 by AMPK has a role in the stimulation of glycolysis during ischaemia. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00742-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, et al. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 2008;133:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luczak ED, Anderson ME. CaMKII oxidative activation and the pathogenesis of cardiac disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;73:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meng Z, Li T, Ma X, Wang X, Van Ness C, et al. Berbamine inhibits the growth of liver cancer cells and cancer-initiating cells by targeting Ca(2)(+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2067–2077. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan LB, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial metabolism in TCA cycle mutant cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2013;13 doi: 10.4161/cc.27513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Britschgi A, Bill A, Brinkhaus H, Rothwell C, Clay I, et al. Calcium-activated chloride channel ANO1 promotes breast cancer progression by activating EGFR and CAMK signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E1026–1034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217072110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knight JA, Onay UV, Wells S, Li H, Shi EJ, et al. Genetic variants of GPX1 and SOD2 and breast cancer risk at the Ontario site of the Breast Cancer Family Registry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:146–149. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarsour EH, Kalen AL, Xiao Z, Veenstra TD, Chaudhuri L, et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase regulates a metabolic switch during the mammalian cell cycle. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3807–3816. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai Y, Martens GA, Hinke SA, Heimberg H, Pipeleers D, et al. Increased oxygen radical formation and mitochondrial dysfunction mediate beta cell apoptosis under conditions of AMP-activated protein kinase stimulation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damelin LH, Coward S, Kirwan M, Collins P, Selden C, et al. Fat-loaded HepG2 spheroids exhibit enhanced protection from Pro-oxidant and cytokine induced damage. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:723–734. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo H, Chen Y, Liao L, Wu W. Resveratrol protects HUVECs from oxidized-LDL induced oxidative damage by autophagy upregulation via the AMPK/SIRT1 pathway. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2013;27:189–198. doi: 10.1007/s10557-013-6442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kang MC, Wijesinghe WA, Lee SH, Kang SM, Ko SC, et al. Dieckol isolated from brown seaweed Ecklonia cava attenuates type capital I, Ukrainiancapital I, Ukrainian diabetes in db/db mouse model. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;53:294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marosi K, Bori Z, Hart N, Sarga L, Koltai E, et al. Long-term exercise treatment reduces oxidative stress in the hippocampus of aging rats. Neuroscience. 2012;226:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zarse K, Schmeisser S, Groth M, Priebe S, Beuster G, et al. Impaired insulin/IGF1 signaling extends life span by promoting mitochondrial L-proline catabolism to induce a transient ROS signal. Cell Metab. 2012;15:451–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chetboun M, Abitbol G, Rozenberg K, Rozenfeld H, Deutsch A, et al. Maintenance of redox state and pancreatic beta-cell function: role of leptin and adiponectin. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:1966–1976. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernard D, Monte D, Vandenbunder B, Abbadie C. The c-Rel transcription factor can both induce and inhibit apoptosis in the same cells via the upregulation of MnSOD. Oncogene. 2002;21:4392–4402. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saccani S, Pantano S, Natoli G. Two waves of nuclear factor kappaB recruitment to target promoters. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1351–1359. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.12.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vrailas-Mortimer A, del Rivero T, Mukherjee S, Nag S, Gaitanidis A, et al. A muscle-specific p38 MAPK/Mef2/MnSOD pathway regulates stress, motor function, and life span in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2011;21:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Na HK, Kim EH, Jung JH, Lee HH, Hyun JW, et al. (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate induces Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzyme expression via activation of PI3K and ERK in human mammary epithelial cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;476:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drane P, Bravard A, Bouvard V, May E. Reciprocal down-regulation of p53 and SOD2 gene expression-implication in p53 mediated apoptosis. Oncogene. 2001;20:430–439. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Negoro S, Kunisada K, Fujio Y, Funamoto M, Darville MI, et al. Activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced oxidative stress through the upregulation of manganese superoxide dismutase. Circulation. 2001;104:979–981. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.095947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eldridge A, Fan M, Woloschak G, Grdina DJ, Chromy BA, et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase interacts with a large scale of cellular and mitochondrial proteins in low-dose radiation-induced adaptive radioprotection. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1838–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen CH, Liu K, Chan JY. Anesthetic preconditioning confers acute cardioprotection via up-regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase and preservation of mitochondrial respiratory enzyme activity. Shock. 2008;29:300–308. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181454295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koch OR, De Leo ME, Borrello S, Palombini G, Galeotti T. Ethanol treatment up-regulates the expression of mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase in rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:1356–1365. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lawler JM, Kwak HB, Kim JH, Suk MH. Exercise training inducibility of MnSOD protein expression and activity is retained while reducing prooxidant signaling in the heart of senescent rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1496–1502. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90314.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reddi AR, Culotta VC. SOD1 integrates signals from oxygen and glucose to repress respiration. Cell. 2013;152:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao F, Mancuso A, Bui TV, Tong X, Gruber JJ, et al. Imatinib resistance associated with BCR-ABL upregulation is dependent on HIF-1alpha-induced metabolic reprograming. Oncogene. 2010;29:2962–2972. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burgess A, Vigneron S, Brioudes E, Labbe JC, Lorca T, et al. Loss of human Greatwall results in G2 arrest and multiple mitotic defects due to deregulation of the cyclin B-Cdc2/PP2A balance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12564–12569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914191107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.