This study evaluated the knowledge of cancer pain management in oncologists and specialists in hospice and palliative medicine and in pain medicine through a survey including vignettes that depicted cancer patients with complex chronic pain conditions. The findings raise serious concerns about the depth of knowledge of various pain treatment choices depicted in the vignettes and underscore a need for education of specialists who treat cancer pain and for more effective referral to specialists with knowledge of cancer pain.

Keywords: Oncologists, Chronic cancer pain, Pain management, Palliative care, Surveys, United States

Abstract

Background.

Cancer pain is usually managed by oncologists, occasionally with input from specialists in hospice and palliative medicine (PLM) or pain medicine (PMD). We evaluated the knowledge of cancer pain management in these three specialty groups.

Methods.

Eight vignettes depicting challenging scenarios of patients with poorly controlled pain were developed; each had five or six treatment choices. Respondents indicated choices likely to be safe and efficacious as “true” and choices likely to be unsafe or inefficacious as “false.” Two questionnaires were created, each with four vignettes. Three anonymous mailings targeted geographically representative U.S. samples of 570 oncologists, 266 PMD specialists, and 280 PLM specialists, each randomly assigned one version of the questionnaire. Vignette scores were normalized to a 0–100 numeric rating scale (NRS); a score of 50 indicates that the number of correct choices equals the number of incorrect choices (consistent with guessing).

Results.

Overall response rate was 49% (oncologists, 39%; PMD specialists, 48%; and PLM specialists, 70%). Average vignette score ranges were 53.2–66.5, 45.6–65.6, and 50.8–72.0 for oncologists, PMD specialists, and PLM specialists, respectively. Oncologists scored lower than PLM specialists on both questionnaires and lower than PMD specialists on one. On a 0–10 NRS, oncologists rated their ability to manage pain highly (median 7, with an interquartile range [IQR] of 5–8). Lower ratings were assigned to pain-related training in medical school (median 3, with an IQR of 2–5) and residency/fellowship (median 5, with an IQR of 4–7). Oncologists older than 46–47 years rated their training lower than younger oncologists.

Conclusion.

These data suggest that oncologists and other medical specialists who manage cancer pain have knowledge deficiencies in cancer pain management. These gaps help clarify the need for pain management education.

Implications for Practice:

We conducted a survey regarding knowledge of managing chronic cancer pain. This survey was mailed to U.S. samples of three groups of medical specialties, that is, oncologists, specialists in pain medicine, and specialists in hospice and palliative care. The survey included vignettes that depicted cancer patients with complex chronic pain conditions. Our findings raise serious concerns about the depth of knowledge of various pain treatment choices depicted in the vignettes and underscore a need for education of specialists who treat cancer pain and for more effective referral to specialists with knowledge of cancer pain.

Introduction

Chronic pain is highly prevalent among populations with metastatic solid tumors [1–6], and pain management is widely considered to be a best practice in oncology. Pain management relies on opioid-based pharmacotherapy, and there is a strong consensus that long-term opioid therapy can provide satisfactory relief to a large majority of patients [7, 8]. Undertreatment is common, however, and is partly determined by limitations in the knowledge and skill of the clinicians who manage pain [9–11]. These limitations may apply to any of a large number of specific treatment practices. For example, a 2014 review of barriers in cancer pain management identified practices such as opioid rotation, the use of adjuvant analgesics, and the management of breakthrough pain as appropriate targets for education to promote favorable outcomes [12].

A recent U.S. survey underscored the need for pain education among medical oncologists [13]. Asked to respond to two vignettes describing challenging clinical scenarios in cancer pain management, 60% and 87% of oncologists, respectively, endorsed treatments that would be considered unacceptable by pain medicine specialists. This survey suggested that vignettes could be used to explore educational needs in pain management.

For the present study, vignettes were developed to evaluate the responses to a group of challenging scenarios in cancer pain management. These vignettes were distributed in a national survey to determine how often oncologists endorse acceptable responses and to compare oncologists’ responses with those of the comparator groups of pain medicine (PMD) specialists and palliative medicine (PLM) specialists.

Materials and Methods

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Beth Israel Medical Center (New York City) determined this study to be exempt from IRB review under the provisions of 45 CFR 46, Section 101(b)(2), which classifies as exempt survey procedures when the information is recorded so that subjects cannot be identified. Data collection was completed in April 2013.

Survey and Study Sample

U.S. national samples of medical oncologists, specialists in PMD, and specialists in PLM were acquired from a database licensee of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Master File (August 14, 2012 update), which includes AMA members and nonmembers from the 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C. We excluded physicians who were characterized as “administrative,” “research,” “medical teaching,” “inactive,” “resident,” and “do not contact.”

Eligible oncologists reported their primary or secondary specialty as medical oncology or hematology and did not list either PMD or PLM as subspecialties. We excluded PMD and PLM specialists from the oncologist group because, until our data were analyzed, we had assumed that these two specialty groups would set the benchmark for what oncologists should know about the management of chronic cancer pain. We also excluded anyone who had been among the 2,000 oncologists on the mailing list of our prior survey [13], because they may have been less likely to respond because they could have felt overburdened by receiving another survey, thus reducing the response rate, and their exposure to the prior survey would have made their results less generalizable to a “naïve” group. Eligible PMD and PLM specialists listed their primary or secondary specialty as pain medicine or palliative medicine, respectively. Physicians in these two groups were not considered eligible for the survey if they also designated the alternate discipline.

Each group of eligible physicians was selected by stratification of U.S. geographic regions into “east,” “west,” “north,” and “south.” A Microsoft T-SQL program (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, http://www.microsoft.com) selected samples randomly from each of the four strata that were proportional to the stratum sizes. The final list included 600 of 8,365 eligible oncologists, 300 of 6,632 eligible PMD specialists, and 300 of 1,025 eligible PLM specialists.

Questionnaire

A questionnaire was developed using a Delphi-like process [14, 15] (supplemental online Appendix 1). Our expert panel included the authors who are medical oncologists (V.T.C., A.I.N., J.H.V.R., and C.v.G.), PMD specialists (R.K.P. and R.K.), and PLM specialists (V.T.C., J.H.V.R., C.v.G., and R.K.P). The vignettes were initially developed by one of the authors (R.K.P) and then revised on the basis of rounds of comments by the other panelists. The vignettes were explicitly developed to assess responses to challenging scenarios that would require high-level knowledge of specific practices related to pain management. Specifically, responses to the cases required knowledge of best practices in systemic opioid therapy, the use of adjuvant analgesics when opioids are insufficient, and the role of interventions. We did not include questions that we considered to be simple and that essentially all practitioners would answer correctly.

A high degree of consensus about the vignettes and the correct responses was reached after two rounds of comments from the expert panel. In the first round, each of the experts was instructed to provide feedback on the instructions used to elicit responses to the vignettes, on each vignette’s readability and clarity, on the level of expertise in pain medicine required to respond correctly, and on the length of time that would likely be needed to respond.

The vignettes were revised based on this input, and for the second round, the panelists received the revised questionnaire, the proposed responses, and the rationale for labeling the response as acceptable or unacceptable. The second round yielded limited changes and consensus that the questionnaire accomplished its aim to examine responses to challenging clinical scenarios encountered in practice.

The eight vignettes assessed a variety of specific practices in cancer pain management. Each depicted a patient with a metastatic solid tumor and a complex pain problem that was poorly controlled using routine first-line analgesic therapy. Each included one or two of the following issues/domains: opioid selection, choice of opioid route, dose titration, management of opioid side effects, treatment of breakthrough or neuropathic pain, pain management in a patient with a substance abuse history, treatment of a pain crisis, and the use of pain intervention to treat refractory pain (supplemental online Appendix 1).

Each vignette was followed by five or six treatment choices. The expert panel agreed that some of these choices were consistent with current best practices and others were not consistent with best practice because of concerns about risk or inefficacy. Given the complexity of the cases, there was no single best option. Respondents were asked to indicate whether each choice was acceptable, that is, likely to be safe and efficacious (labeled as “true”), or unacceptable (labeled as “false”). Instructions discouraged guessing. Respondents were told to leave the item blank if the answer was unknown and no reasonable guess could be made.

Following development by the expert panel, the vignettes underwent additional content validation by one attending physician and one fellow in medical oncology, PMD, and PLM, respectively (n = 6). This experience suggested that completing eight vignettes could be overly burdensome. Accordingly, the vignettes were divided into two sets of four, each requiring approximately 20 minutes to complete. The sets were selected to avoid redundancy of topics within a questionnaire and to be equally difficult, as suggested by the participants’ scores in content validation. The selection culminated in two questionnaires (“questionnaire 1” and “questionnaire 2”), each comprising one of the sets of four vignettes, plus additional questions regarding age, sex, medical specialty, practice location (state), primary treatment setting (comprehensive cancer center, community-based oncology group practice, community-based solo practice, community hospital-based practice, or a teaching hospital-based practice), number of pain-management-related continuing medical education (CME) hours attended in the past year, and frequency of referral to a PMD or PLM specialist (never, rarely, occasionally, or frequently). Respondents also were asked to rate their self-perceived skill in managing chronic cancer pain and the quality of training during medical school and during residency/fellowship, on a 0–10 numeric rating scale (NRS).

Mailings

There were three sequential mailings, with a 2- to 2.5-month intermailing interval. To limit repeated mailings to nonresponders while maintaining anonymity, a cover letter asked the recipients of the first two mailings to return an enclosed postcard—which contained only the respondent’s identification number—separately from the completed questionnaire.

The mailing method for the survey was influenced by the experience of our prior survey [13]. Only the fourth and final mailing for that study was sent via UPS 2-day air mail and included a $10 bill, and its response rate was much higher than for the previous three mailings. The present survey allowed us to determine which change was more important in driving the response rate. Accordingly, the first mailing for the present survey was randomly divided into three methods: (a) UPS 2-day air with a $10 bill, (b) UPS 2-day air without any incentive, or (c) regular first-class mail with a $10 bill. Randomization was performed with the SAS Plan procedure.

Although the distribution of the questionnaires were via mail, we were not concerned about the possibility of the respondents consulting with others about how to answer to the questions. The aim of the vignettes was to simulate actual cases encountered in practice. If a respondent were motivated to ask a colleague about a hypothetical patient, this would likely reflect actual practice patterns and, as such, would be a desirable element in the questionnaire response.

The SAS Surveyselect procedure was used to randomize physicians to receive one of the two questionnaires. The first mailing was sent to the eligible medical oncologists. Based on the results (see below), the second mailing was sent to all three groups via UPS 2-day air with a $10 bill. In an effort to further increase the response rate and generalizability [16], the third mailing included a larger monetary incentive (a $20 bill); this potentially allowed evaluation of systematic nonresponder bias [17] if enough nonresponders from prior mailings responded.

Data Analysis

To reduce the impact of guessing, each response to each vignette was scored +1 if correct, 0 if left blank, and −1 if incorrect. Thus vignette scores ranged from −5 to +5 for vignettes that were followed by five treatment choices and −6 to +6 for vignettes that were followed by six treatment choices.

To facilitate analysis, all scores were normalized: A vignette was scored (a) 0 if all questions were answered incorrectly (prenormalized score of −5 or −6, depending upon the number of treatment choices following the vignette), (b) 100 if all were answered correctly (prenormalized score of +5 or +6), and (c) 50 if the number of correct answers equaled the number of incorrect answers, which would be expected with all guesses. The equation used to calculate the normalized score was as follows: normalized score = (50/number of treatment choices)(prenormalized score) + 50; prenormalized scores vary from −5 to +5 or from −6 to +6.

Because there were no significant differences in the distributions of normalized scores across the three mailings for the entire group, either for each vignette or for the overall score on the four vignettes, the data across mailings were combined for analysis.

SAS, version 9.3, was used for statistical analyses. Bivariate analyses for categorical data were performed using either χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Ordinal and continuous variables were analyzed with nonparametric tests or analysis of variance using the SAS Mixed procedure. Multivariate analysis, with or without repeated measures, also was performed with the SAS Mixed procedure, using the LSMEANS (least squares means) statement, as deemed appropriate. Tukey adjustments were used when all pairwise comparisons were made. Multivariate models included predictors that intuitively could have affected oncologists’ knowledge about cancer pain, as measured by the vignettes, regardless of their p values in the bivariate analyses. We manually conducted stepwise backward elimination until obtaining a model with five predictors and reported their p values. Predictors were deemed significant when p ≤ .050.

The Loess procedure was used to generate scatterplots with overlaid local regression (loess) lines, to check whether there was an age range for oncologists that distinguished higher versus lower ratings of the quality of pain management training during medical school and residency/fellowship; this was evaluated because PMD gained recognition as a medical subspecialty after 1990.

Results

Response Rates

Three physicians indicated on their surveys subspecialties that had not been reported on our AMA file. For all analyses, the oncologist who also listed pain medicine as a subspecialty on the survey was reclassified as a PMD specialist, and the two oncologists who listed palliative medicine as a subspecialty were reclassified as PLM specialists.

From the 1,200 initial mailings, 84 were either undeliverable or returned with comments indicating ineligibility; an additional nine physicians refused to participate. From the potentially 1,116 eligible recipients, 550 usable surveys were returned (response rate, 49%). The response rates for specialists in oncology, PMD, and PLM were 39% (225 of 570), 48% (128 of 266), and 70% (197 of 280), respectively.

The first mailing, sent only to oncologists, had a response rate of 14% (85 of 590). The response rates for those sent the mailing via UPS with a $10 incentive, UPS with no incentive, and regular mail with a $10 incentive were 26% (51 of 198), 0.5% (1 of 195), and 17% (33 of 197), respectively.

The response rates for the second mailing were 19% (92 of 495), 33% (94 of 284), and 51% (146 of 288) for oncology, PMD, and PLM specialists, respectively (overall rate, 31% [332 of 1,067]). Corresponding rates for the third mailing were 13% (51 of 393), 19% (33 of 172), and 37% (49 of 134) (overall rate, 19% [133 of 699]).

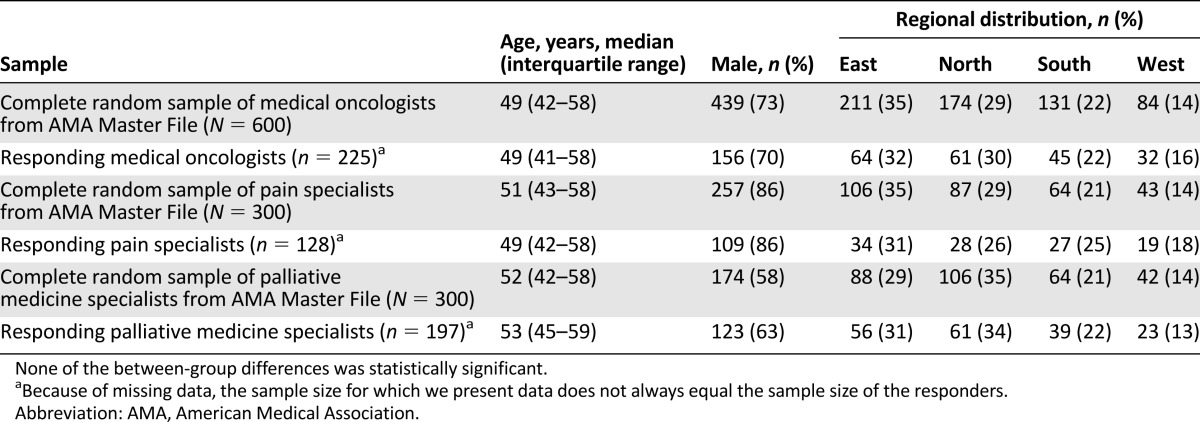

Several findings suggest that the survey respondents were representative of their respective source populations. First, the distributions of age, sex, and practice location for each specialty group are similar to the respective distributions in the AMA list (Table 1). Second, each mailing after the first yielded statistically similar percentages of responders from each specialty: For the second and third mailings, among responders, 28% and 38% were oncologists, 29% and 25% were PMD specialists, and 44% and 37% were PLM specialists. Third, across all mailings, for each specialty, responses to the additional questions accompanying the vignettes were statistically similar, except for an increase in the percentage of male oncologists between the first and third mailings (57%, 73%, and 84%; p = .003).

Table 1.

Comparison of the study samples of oncologists, pain specialists, and palliative medicine specialists (n = 225, 128, and 197, respectively) to the respective complete random samples from AMA Master File groups (n = 600, 300, and 300, respectively) from which each study sample was drawn with respect to distribution of age, sex, and U.S. region of practice

Respondent Characteristics

On a 0–10 NRS, oncologists rated their ability to manage cancer pain higher (median 7, with an interquartile range [IQR] of 5–8) than did PMD specialists (median 6, with an IQR of 5–8); self-ratings by PLM specialists were highest (median 8, with an IQR of 7–8) (Table 2). The mean (SE) number of cancer patients treated by PMD specialists each month (9.3 [9.9]) was significantly lower than that for oncologists (174 [7.3]; p < .001) and PLM specialists (54 [7.9]; p < .001). Of oncologists, 28% frequently sought help in managing their cancer patients’ pain by referring to PMD specialists, and 34% frequently referred to PLM specialists.

Table 2.

Responses to the additional questionnaire items (Ntotal = 550)

The ratings for training in cancer pain management in medical school and during residency/fellowship were lower for PLM specialists than oncologists (change in mean [SE] ratings −1.7 [0.2], p < .001 for medical school and −1.1 [0.3], p < .001 for residency/fellowship) and lower for PLM specialists than PMD specialists (−-0.6 [0.2], p = .03 for medical school and −1.6 [0.3], p < .001 for residency/fellowship). According to the Loess procedure’s “fit plots,” older oncologists rated the adequacy of training in cancer pain management lower than younger oncologists; oncologists older than 46 years (for postgraduate training) or 47 years (for medical school training) assessed training in pain management as less adequate than younger oncologists (p < .001 for each).

Responses to Vignettes

Cronbach’s α was 0.7 for questionnaire 1 and 0.6 for questionnaire 2, indicating acceptable internal consistency [18]. Questionnaire 1 had 257 respondents and 23 treatment choices (5 treatment choices following the first vignette and 6 for each of the three others), totaling 5,911 potential answers (257 × 23). Questionnaire 2 had 293 respondents and 21 treatment choices (6 following the first vignette and 5 for each of the three others), totaling 6,153 potential responses (293 × 21). Of the 5,911 potential answers in questionnaire 1, 909 (15%) were blank (oncologists, 18%; PMD specialists, 23%; and PLM specialists, 8%); of the 6,153 in questionnaire 2, 582 (9%) were blank (oncologists, 11%; PMD specialists, 10%; and PLM specialists, 7%).

For the oncologists, the mean (SE) normalized scores for all 8 vignettes ranged from 53.2 (1.9) to 66.5 (2.1) (Table 3). The vignette about opioid dose titration and management of a patient with substance use disorder yielded a score that was significantly higher than each of the other vignettes in the questionnaire. There were no other significant differences across vignettes in the oncologists’ mean normalized scores.

Table 3.

Mean normalized scores for oncologists for each topic within each questionnaire

Tables 4 and 5 present the scores of the oncologists and each of the other two specialty groups for each of the eight vignettes. The overall scores of oncologists were lower than those of PLM specialists on both questionnaires and lower than those of PMD specialists on one questionnaire.

Table 4.

Relationship between topic scores and medical specialty for questionnaire 1 (n = 257)

Table 5.

Relationship between topic scores and medical specialty for questionnaire 2 (n = 293)

Oncologists whose primary treatment setting was a comprehensive cancer center scored significantly higher on questionnaire 1 than those primarily working at a community-based solo practice (score difference [SE], 7.5 [2.6]; p = .03). On questionnaire 2, those who worked primarily in a community-based oncology group practice scored lower than those in a community-based solo practice (score difference [SE], −6.0 [1.8]; p = .01) and those in a community hospital-based practice (score difference [SE], −8.6 [1.8]; p < .001). The total score on questionnaire 2 also was significantly related to male sex (p = .04) and to the number of pain-related CME hours during the last year (r = 0.17; p = .005); it was inversely related to the number of cancer patients seen monthly (r = −0.19; p = .002).

In multivariate analyses, the normalized overall score was related to medical specialty in one questionnaire and to the rating of postgraduate pain management training and treatment setting in the other (Table 6). In analyses limited to oncologists, the score on one of the questionnaires was related to the frequency of referring to PMD specialists, and the score on the other was inversely related to the number of cancer patients treated monthly.

Table 6.

Results of multivariate analysis

Discussion

This survey provides the first assessment of medical oncologists’ knowledge about cancer pain management relative to PMD specialists and PLM specialists. The vignettes were designed to query responses to challenging cases, those characterized by severe pain that had not responded to a conventional first-line approach using a systemic opioid. Applying an analysis that interprets a normalized score of 50 as guessing, the mean (SE) scores for the oncologists ranged from 53.2 (1.9) to 66.5 (2.1). Relatively few items were left blank, suggesting that respondents usually did not perceive their responses were guesses.

These scores raise concerns about the depth of knowledge related to the various treatment strategies depicted in the vignettes and underscore a need for oncologist education in pain medicine. The findings are consistent with a U.S. survey of second-year oncology fellows, which noted that only 33% reported receiving explicit education on opioid rotation, and only 23% correctly performed an opioid conversion [19].

There were no consistent findings linking demographic or practice patterns to vignette scores. The response patterns do not help target those practice areas most in need of education, but the age-related decline in the ratings of pain education in medical school and residency/fellowship suggests that oncologists who trained prior to the emergence of pain medicine and palliative medicine as subspecialties are most likely to benefit. Although analyses also suggested that frequent referrals to PMD specialists and fewer patients treated monthly may be predictors of higher knowledge among oncologists, this is tentative given the differences in the results across the questionnaire versions.

Unexpectedly, the scores recorded by specialists in PMD or PLM also were relatively low, suggesting a more general need for education. PMD specialists have much less exposure to cancer patients than PLM specialists, and their scores were understandably lower. The extent to which referral to PMD specialists might be used generally to address refractory pain problems is uncertain. Only approximately one-third of oncologists referred frequently to PLM specialists, and although this value is double that identified in our prior survey [13], it is relatively low and suggests that oncologists also seldom seek help from PLM specialists for complex pain management problems. Increased consultations with PLM specialists may be valuable [20], but our results also highlight the need for further education of these specialists. A Medline search of publications from 1996 to the present yielded no publications about the knowledge or quality of PLM specialists’ management of cancer pain, and additional research will be needed to clarify the extent to which education and training in pain management should target the growing U.S. community of PLM specialists.

When considering the results of this study, some important limitations must be taken into account. First, the questionnaires were not subjected to formal validation. Content validation by appropriate clinicians and the ability to detect differences between PLM specialists and others in both the pilot study and the full study, that is, discriminant validity, suggest that the tool is measuring knowledge of the type that translates into clinical practice, but validation through an assessment of the relationship between test scores and patient outcomes could not be done in this initial study. Second, like most surveys of professionals, the response rates were not high, and adequate information to evaluate nonresponse bias may be lacking.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the limitations of this study and the need for additional research to assess the extent to which education in pain management can improve patient outcomes, this work suggests that medical oncologists, as well as other medical specialists who treat the pain of advanced cancer patients, may lack the knowledge necessary to manage challenging cancer pain syndromes. The results support efforts at targeted education of oncologists and more effective referral to specialists with specific knowledge of cancer pain.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This survey was funded by a grant from Covidien Pharma (Hazelwood, MO).

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Brenda Breuer, Victor T. Chang, Jamie H. Von Roenn, Charles von Gunten, Alfred I. Neugut, Ronald Kaplan, Sylvan Wallenstein, Russell K. Portenoy

Provision of study material or patients: Brenda Breuer

Collection and/or assembly of data: Brenda Breuer

Data analysis and interpretation: Brenda Breuer, Victor T. Chang, Jamie H. Von Roenn, Charles von Gunten, Alfred I. Neugut, Ronald Kaplan, Sylvan Wallenstein, Russell K. Portenoy

Manuscript writing: Brenda Breuer, Victor T. Chang, Jamie H. Von Roenn, Charles von Gunten, Alfred I. Neugut, Ronald Kaplan, Sylvan Wallenstein, Russell K. Portenoy

Final approval of manuscript: Brenda Breuer, Victor T. Chang, Jamie H. Von Roenn, Charles von Gunten, Alfred I. Neugut, Ronald Kaplan, Sylvan Wallenstein, Russell K. Portenoy

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Faris M, Al Bahrani B, Emam KA, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence, pattern and management of cancer pain in Oncology Department, The Royal Hospital, Oman. Gulf J Oncolog. 2007;1:23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mercadante S, Roila F, Berretto O, et al. Prevalence and treatment of cancer pain in Italian oncological wards centres: A cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1203–1211. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Z, Lian Z, Zhou W, et al. National survey on prevalence of cancer pain. Chin Med Sci J. 2001;16:175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck SL, Falkson G. Prevalence and management of cancer pain in South Africa. Pain. 2001;94:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: A systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goudas LC, Bloch R, Gialeli-Goudas M, et al. The epidemiology of cancer pain. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:182–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swarm RA, Paice J, Anghelescu DL et al. NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2014 Updates Adult Cancer Pain. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2014.

- 8.Miaskowski C, Bair M, Chou R, et al. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. 6th ed. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MP. Integrating palliative medicine into an oncology practice. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2005;22:447–456. doi: 10.1177/104990910502200611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oldenmenger WH, Sillevis Smitt PA, van Dooren S, et al. A systematic review on barriers hindering adequate cancer pain management and interventions to reduce them: A critical appraisal. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1370–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pargeon KL, Hailey BJ. Barriers to effective cancer pain management: A review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:358–368. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon JH. Overcoming barriers in cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1727–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breuer B, Fleishman SB, Cruciani RA, et al. Medical oncologists’ attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: A national survey. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4769–4775. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Villiers MR, de Villiers PJ, Kent AP. The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Med Teach. 2005;27:639–643. doi: 10.1080/13611260500069947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voigt LF, Koepsell TD, Daling JR. Characteristics of telephone survey respondents according to willingness to participate. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:66–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hair JE, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, et al. Multivariate Data Analysis. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buss MK, Lessen DS, Sullivan AM, et al. Hematology/oncology fellows’ training in palliative care: Results of a national survey. Cancer. 2011;117:4304–4311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy MH, Back A, Benedetti C, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:436–473. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.