Abstract

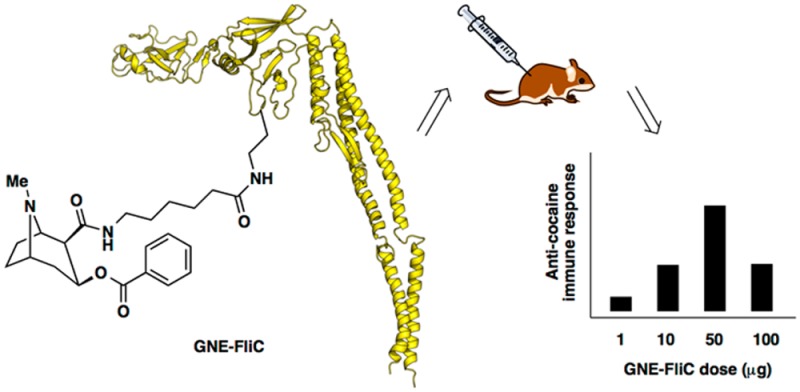

Cocaine abuse is problematic, directly and indirectly impacting the lives of millions, and yet existing therapies are inadequate and usually ineffective. A cocaine vaccine would be a promising alternative therapeutic option, but efficacy is hampered by variable production of anticocaine antibodies. Thus, new tactics and strategies for boosting cocaine vaccine immunogenicity must be explored. Flagellin is a bacterial protein that stimulates the innate immune response via binding to extracellular Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) and also via interaction with intracellular NOD-like receptor C4 (NLRC4), leading to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Reasoning that flagellin could serve as both carrier and adjuvant, we modified recombinant flagellin protein to display a cocaine hapten termed GNE. The resulting conjugates exhibited dose-dependent stimulation of anti-GNE antibody production. Moreover, when adjuvanted with alum, but not with liposomal MPLA, GNE-FliC was found to be better than our benchmark GNE-KLH. This work represents a new avenue for exploration in the use of hapten-flagellin conjugates to elicit antihapten immune responses.

Keywords: addiction, adjuvant, antibody, carrier protein, cocaine, conjugate, dose−response, flagellin, hapten, immunogenicity, mice, vaccine

Introduction

According to the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), there were an estimated 1.4 million cocaine users in the United States.1 Overall, substance abuse costs exceed $600 billion annually, but treatment can help reduce these costs.2 Medications exist for treating withdrawal symptoms, and counseling therapies can be used to modify a patient’s attitude and behaviors regarding their addiction. However, even with these therapies, it is extremely difficult for cocaine addicts to remain abstinent. Thus, there is great need for more effective treatment options.3 Therapies currently in development include drugs that act as agonists or antagonists (to mimic or compete with cocaine), esterases4 (to hydrolyze cocaine), and antibodies (to sequester cocaine in the periphery and/or set up a concentration gradient that draws cocaine out of the brain). By targeting cocaine itself, rather than brain receptors, antibody-based therapies tend to have fewer side effects.

Currently, vaccines against cocaine and other drugs of abuse are being developed.5 Such vaccines stimulate the immune system to produce highly specific antibodies that bind drug molecules in systemic circulation. Antibodies typically cannot cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB); thus, antibody-bound drug is prevented from crossing the BBB. This spares the brain reward system6 and reduces the reinforcing effects of the drug. Also, in drug overdose situations, passive immunization with an anticocaine monoclonal antibody may lessen the severity of overdose symptoms.7

Clinical studies of TA-CD, an alum-adjuvanted cocaine vaccine,8 have provided insight into the challenges that anticocaine vaccines face. In a phase IIb trial of TA-CD, 38% of the trial population, individuals with the highest anticocaine IgG concentrations (≥43 μg/mL), had significantly more cocaine-free urine samples than the other 62% of vaccinated subjects or the placebo group.9 Nevertheless, subsequent trials failed to meet their primary end points, and further development of TA-CD has been halted. In order for a cocaine vaccine to be clinically successful, it must be broadly efficacious. As such, it should aim to achieve therapeutic antibody levels in all vaccinated patients. A major current focus for vaccine improvement is the evaluation of adjuvants, which help by triggering more robust immune responses and are particularly useful when a nonadjuvanted vaccine antigen is only modestly immunogenic at best.10

For cocaine vaccines, existing alternatives to alum adjuvant include SAS,11 RhinoVax,12 and a lipopeptide,13 the latter reportedly being evaluated by Orson et al.10c Opportunities for rational vaccine design have been greatly expanded by the elucidation of several major signaling pathways involved in innate and adaptive immunity. Particularly, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are becoming widely regarded as key role players in regulating innate and adaptive immune responses to antigens, and the direct targeting of TLRs via carefully constructed subunit vaccines has become an area of intense scientific inquiry.14 Furthermore, combinations of adjuvants are being studied in an effort to achieve synergy in stimulation of the desired immune response. Indeed, simultaneous targeting of multiple nonredundant (e.g., TLR and non-TLR) pathways can boost the immune response to a given antigen.15

Our current strategy was to use flagellin in a dual role as carrier and adjuvant because it is both a potent immunostimulant and a protein to which haptens may be covalently attached.16 Flagellin, a major structural protein of bacterial flagella, consists of a hypervariable domain (HVD) flanked by conserved N- and C-terminal domains, which bind to Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5).17 TLR5, the only protein-binding TLR, is conserved across most invertebrates and is found mainly on epithelial cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells, but also on T cells.18 Binding of flagellin to TLR5 induces MyD88-dependent TH2 cytokine production.19 Meanwhile, flagellin also signals via the NLRC4 inflammasome, a MyD88-independent mechanism for innate immune signaling.20 There is very recent evidence that a third nonredundant pathway may be involved in flagellin-mediated immune responses.21 Importantly, prior exposure to flagellin does not induce tolerance.22

Early studies of flagellin binding demonstrated that peptide sequences could be inserted into the HVD of flagellin without affecting binding function, opening up the possibility of using flagellin fusion proteins, exploiting conjugation chemistry, and other applications.23 Indeed, recombinant antigen-flagellin fusion protein vaccine formulations have been directed against a variety of bacterial (Clostridium difficile,24Pseudomonas aeruginosa,25 and Yersinia pestis(26)) and viral (influenza,27 vaccinia,28 and West Nile29) pathogenic threats. In these cases, flagellin was shown to increase antibody-dependent protective responses resulting in significantly higher antibody titers. Importantly, from a clinical standpoint, flagellin fusion proteins are safe, well tolerated, and efficacious even at low doses.27a,30

Beyond our attraction to flagellin as an adjuvant, per se, we envisioned that a hapten-flagellin conjugate would meanwhile adhere to the principle of colocalization of antigen and adjuvant for maximizing the immune response.31 In fact, Huleatt et al. have already shown that one must attach antigen directly to flagellin in order to reap the adjuvant benefit; the corresponding admixture failed to augment the immune response.22a Therefore, we hypothesized that recombinant flagellin protein, suitably decorated with cocaine haptens, would represent a potent means for achieving enhanced anticocaine antibody production.

Materials and Methods

Expression and Purification of Recombinant FliC

The bacterial strain Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC #13076), and genomic DNA was prepared from bacterial cultures (PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit from Invitrogen). The flagellin gene fliC was amplified by PCR and subcloned into the pET29a expression vector (Novagen) using NdeI and BamHI restriction sites thereby appending a C-terminal His tag as previously described.32 The recombinant flagellin protein FliC was overexpressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells and purified using TALON cobalt metal affinity resin (Clontech) under denaturing conditions. In brief, ∼12 g of cell paste was resuspended in 225 mL of extraction/wash buffer consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 6 M guanidine-HCl, and 300 mM NaCl (buffer A). Following clarification by centrifugation, the supernatant was added to pre-equilibrated TALON resin and batch bound. After washing with buffer A, the protein was eluted with 75 mL of elution buffer consisting of 45 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 5.4 M guanidine-HCl, 270 mM NaCl, and 150 mM imidazole (buffer B). The eluted protein was dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Endotoxin was removed by performing 1% (v/v) Triton X-114 extractions33 followed by dialysis against 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The protein was lyophilized until dry and stored at −20 °C. Upon reconstitution in PBS, pH 7.4, FliC was qualitatively evaluated by SDS-PAGE (purity of >95% homogeneity) and quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce). The endotoxin level was measured with the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Thermo Scientific) and determined to be <1 pg/μg of protein. Additionally, a gel band was submitted to trypsin digest and MS/MS proteomics analysis to confirm the identity of the protein as phase-1 Salmonella flagellin.

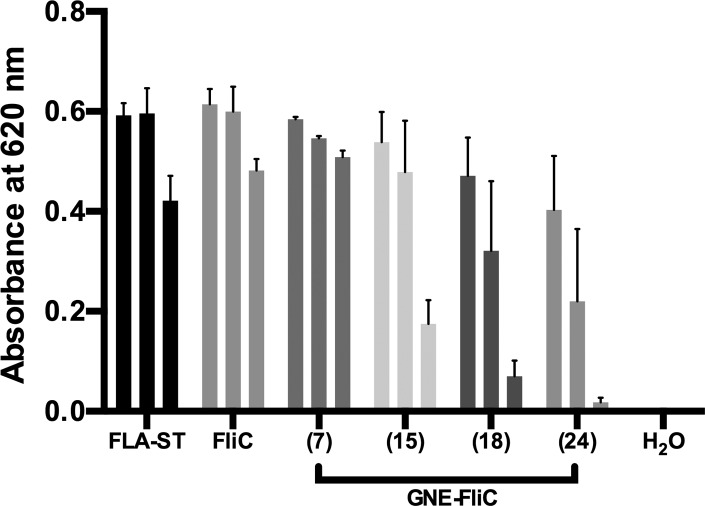

mTLR5 Reporter Assay

HEK-Blue mTLR5 cells (InvivoGen) provide a TLR5-specific gene reporter assay system relying on TLR5 stimulation by TLR5 agonists and were used to determine the ability of our recombinant FliC to stimulate TLR5 before and after hapten conjugation. Colorimetric assays were conducted in 96-well plates with ∼2.5 × 104 cells per well and FliC concentrations of 100, 50, and 10 ng/mL in the presence of HEK-Detection Medium (InvivoGen) as specified by the manufacturer. After incubation for 7 h, absorbance was recorded at 620 nm to quantify TLR5 stimulation. Commercial flagellin (FLA-ST Ultrapure, InvivoGen) was used a positive control; water was used as a negative control. Recombinant FliC and GNE-FliC conjugates prepared in this study were similarly evaluated.

Preparation of GNE-FliC Conjugates

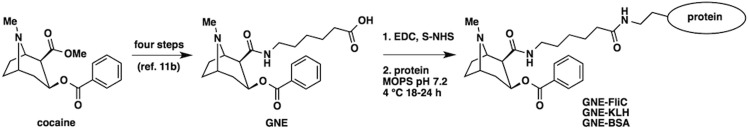

The cocaine hapten GNE was synthesized from cocaine (NIDA Drug Supply Program), activated using standard conditions,11,34 and conjugated to available lysine residues on flagellin. Lyophilized FliC was reconstituted in PBS pH 7.4 to ∼5 mg/mL, then dialyzed against MOPS pH 7.2 buffer prior to use in conjugations. Flagellin was then aliquoted into clean microtubes, and sulfo-NHS activated GNE was added at a ratio of 1:1 (GNE to flagellin by weight; molar ratio is 1:137) and gently shaken at 4 °C for 18–24 h. Similarly, GNE-BSA and GNE-KLH were prepared (Scheme 1). After conjugation, each GNE-protein conjugate was dialyzed against PBS using a Slide-A-Lyzer 10K MWCO dialysis device. After 2 h, the buffer was exchanged, and dialysis was continued overnight. Conjugates were quantified by BCA assay (Pierce) and stored at 4 °C until further use.

Scheme 1. Preparation of GNE Conjugates to FliC, KLH, and BSA.

Hapten synthesis is reported elsewhere. (1) Hapten GNE was activated using EDC and sulfo-NHS in DMF/H2O at room temperature for 4 h. (2) Activated hapten was then mixed with protein (FliC, KLH, or BSA) in MOPS buffer pH 7.2 at 4 °C for 18–24 h.

Mass Spectral Analysis

In order to quantify hapten density for GNE-FliC conjugates prepared in this study, samples were routinely submitted for MALDI-TOF and ESI-TOF MS analysis and compared with unmodified FliC, as per the formula: hapten density = (MWGNE-FliC – MWFliC)/(MWGNE – MWwater); MWFliC = 55246 Da.

Fluorometric Assay

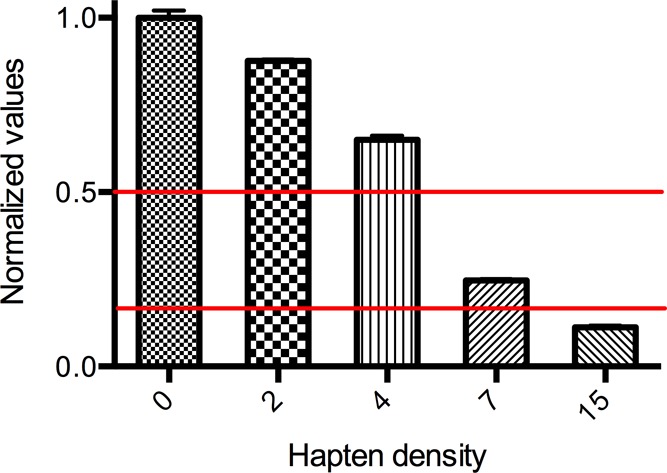

The fluorometric assay of FliC and GNE-FliC conjugates was performed in Costar 96-well black clear-bottom plates. Each well was filled with 200 μL of PBS-buffer (pH 7.4). Twenty micrograms of FliC or GNE-FliC conjugate in PBS-buffer was added, followed by 5 μL of a freshly prepared fluorescamine in DMSO solution (10 mg/mL), mixed well and analyzed after 5 min. BSA calibration curves were routinely measured prior to FliC analysis as quality control. Fluorescence end point analysis was performed on a SpectraMax M2e microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with the settings as follows: excitation, λ = 400 nm; emission, λ = 475 nm; cutoff, λ = 455 nm; speed, normal; reads/well, 30; bottom read. Assays were independently performed in triplicate and obtained values normalized to unconjugated FliC. Relative average values with standard deviation are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Estimation of the relative hapten density by a fluorometric assay. Given hapten densities were obtained from MALDI-MS spectra. Each assay was performed in triplicate and average values with standard deviation are depicted.

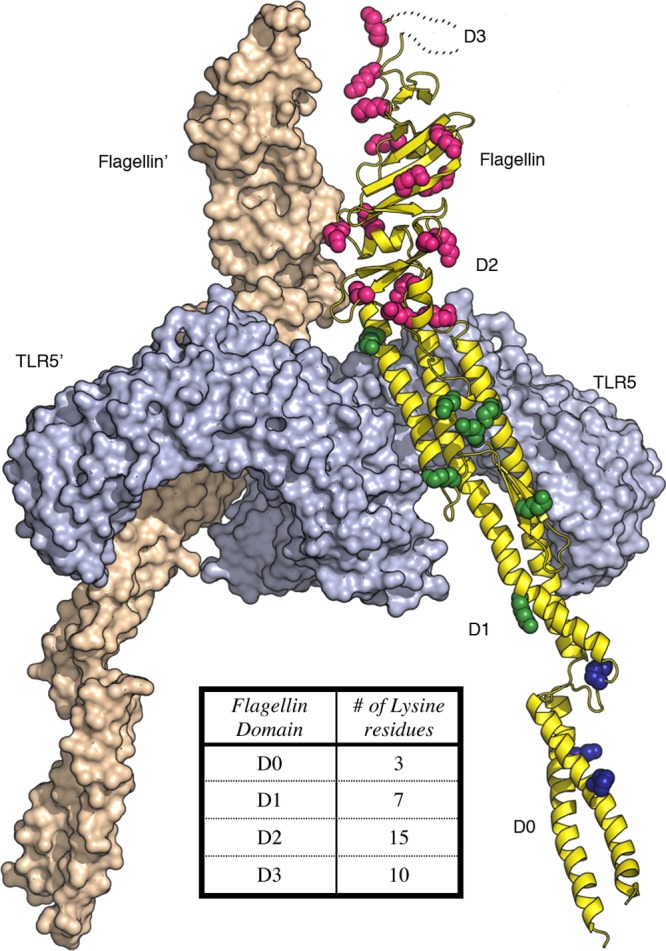

Modeling and Computational Analysis of GNE-FliC

In order to gain an appreciation for the nature of flagellin binding to TLR5, with and without GNE cocaine haptens present, we constructed a homology model and performed computational analysis (i.e., number of lysines per domain and relative solvent accessibility). A homology model of Salmonella flagellin enterica serovar Dublin including the D0 domain was created in Modeler.35 The homology model was generated using the structure of full-length Salmonella flagellin enterica serovar Typhimurium (PDB accession code 3A5X(36)) as the model for the D0 domain and the crystal structure of Salmonella flagellin enterica serovar Dublin ΔD0 in complex with the N-terminal fragment of zebrafish TLR5 (PDB accession code 3V47(17a)). The D0 domains of Salmonella flagellin enterica serovar Dublin and enterica serovar Typhimurium are conserved (94% identical, 99% similar). The final homology model contains flagellin D0-D1-D2 domains, but not the hypervariable D3 because there is no homologous template structure for this domain. We analyzed the spatial distribution of flagellin lysine residues in the context of the flagellin-TLR5 complex and calculated solvent accessible surface area for each lysine in our homology model.

Preparation of Vaccine Formulations

For the dose-ranging aspect of our study of GNE-FliC in mice, we simply diluted GNE-FliC in PBS pH 7.4 to final concentrations of 1000, 500, 100, and 10 μg/mL. For these four groups, since no additional adjuvant was incorporated, the injection volume was 100 μL per mouse. As such, each mouse received a dose of 100, 50, 10, or 1 μg GNE-FliC, respectively. For the adjuvant formulation aspect of our study, both alum and liposomal MPLA were evaluated, and in these cases, injection volume was 200 μL per mouse. Two of these groups were given either GNE-FliC or GNE-KLH (100 μg per mouse), using 1 mg/mL GNE-protein conjugate mixed with an equal volume of Imject Alum Adjuvant (Thermo Scientific). Finally, two of these groups were given GNE-FliC (10 or 50 μg per mouse), using either 50 or 250 μg/mL GNE-FliC formulated in liposomal MPLA. Liposomal MPLA37 was prepared as follows: the four components (DMPC, cholesterol, DMPG, synthetic MPLA, all from Avanti Polar Lipids) were combined at a molar ratio of 9 to 7.5 to 1 to 0.0454 in chloroform/methanol, concentrated under reduced pressure on a rotary evaporator to a thin lipid film, then left under high vacuum overnight to remove trace organic solvent, then rehydrated with PBS pH 7.4 using the freeze–thaw–vortex method (three cycles), and combined with GNE-FliC to achieve the above-specified concentrations. The liposomal formulations produced in this manner had 40 μg of MPLA per dose.

Experimental Animals

Thirty male BALB/cByJ mice were obtained from the internal TSRI breeding colony. Mice were transferred to arrive at 7–8 weeks of age and were housed 4/cage in a temperature- and humidity-controlled, Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) accredited, vivarium facility within a room maintained on a 12:12 h reverse light cycle (lights off 9:00 AM). Food and water were available ad libitum in microisolator cages enriched with cut 3 in. PVC tubing. All procedures were approved by TSRI’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and performed in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Vaccination Protocols

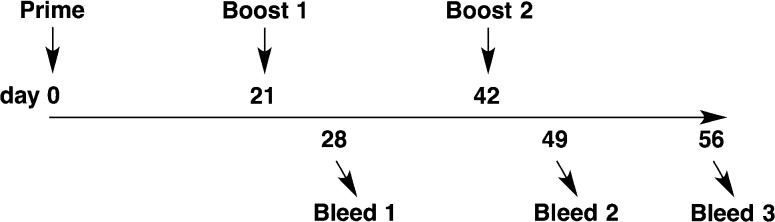

Mice (n = 3–5 per group) were given subcutaneous injections (100 or 200 μL total volume) at 0, 3, and 6 weeks (Figure 1). Nonterminal bleeds (tail tip amputation, ∼0.2 mL) were collected at 4 and 7 weeks, and a terminal bleed (cardiac puncture, ∼1.25 mL) was collected at 8 weeks.

Figure 1.

Mouse vaccination and bleed schedule.

Body Weight

Mouse weights were monitored over the time course of study, concurrent with injection schedule.

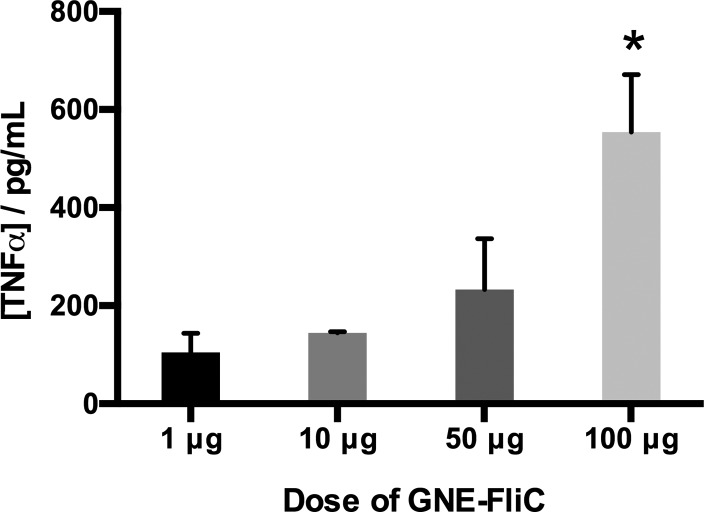

Luminex Assay

Because animals receiving the highest dose of GNE-FliC exhibited symptoms of compromised health (e.g., lack of healthy weight gain), we elected to perform a multiplex assay of cytokine levels. Mouse sera (bleed 1) were subjected to a Luminex assay in which eight cytokines were measured: IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12(p70), IFNγ, and TNFα.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The anti-GNE antibody response was characterized by ELISA using horseradish peroxidase conjugated donkey antimouse IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 715-035-151) as described elsewhere.11a

Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

The anticocaine binding affinity and concentration were quantified by equilibrium dialysis using 3H-radiolabeled cocaine (PerkinElmer, NET510250UC) as described elsewhere.11a Because of the volume requirements for RIA, only the terminal bleed (bleed 3) was analyzed by RIA, and samples were pooled for each vaccine group. Thus, the results are average antibody affinities and concentrations.

Statistical Analyses

All data are presented as mean ± standard error (SEM). Where appropriate, data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with treatment as the factor or two-way ANOVA with the repeated measure of time as indicated by the experimental design. Significant ANOVA was followed by posthoc comparison indicated within the figure caption, with significance set at α < 0.05.

Results

To enable our study, we made high quality recombinant flagellin protein (FliC) suitable for vaccine development. During the optimization phase of FliC purification, we occasionally observed a significant lower-lying band on SDS-PAGE (Figure S1, Supporting Information). MS/MS proteomics analysis (Figure S2, Supporting Information) confirmed the protein to be flagellin, albeit with a lack of sequence coverage for both the N- and C-termini, indicative of proteolytic degradation of the D0 domain.38 To prevent this degradation, we avoided storage of flagellin in buffer for extended periods of time. Thus, for long-term storage of recombinant flagellin protein, we employed a protocol of dialysis against ammonium bicarbonate followed by lyophilization until dry and then storage in a −20 °C freezer.

Hapten densities on the order of ∼7 GNE per FliC monomer16a were typically observed (compare Figure S3 with Figure S4, Supporting Information) with a 1:1 hapten to protein ratio (mg basis) when conjugation was performed at 4 °C. Increasing this ratio (e.g., 2:1) and performing the conjugation at room temperature tended to yield GNE-FliC with higher hapten densities (e.g., ∼15 to 20 GNE per FliC monomer).

To develop a simple and straightforward assay to assess the degree of haptenation as an alternative methodology to MALDI-TOF mass spectral analysis, we optimized a fluorometric assay using fluorescamine to label the available lysines on FliC and GNE-FliC conjugates for relative quantification of the available lysine residues.39 Fluorescamine selectively reacts with primary lysine amines and the emission of the fluorescent product can be analyzed at λ = 475 nm. After conjugation, each GNE-FliC conjugate was compared to unconjugated FliC used as standard. As anticipated, fluorescence intensity decreases in correlation with increasing hapten density (Figure 2). Normalized values were calculated, and a range between 0.2 and 0.5 (red lines) was estimated as a suitable hapten density for immunization experiments.

Our flagellin model (Figures 3 and S5, Supporting Information) permitted us to survey the spatial distribution and solvent accessibility of lysine residues. All of the lysine side chains in our model structure are solvent accessible and available for chemical coupling to GNE hapten. The majority of lysine residues in flagellin are located in the variable D2 and D3 domains (25 out of 35 lysine residues). D2 and D3 are not implicated in TLR5 binding and activation; thus, modification of these lysine residues is expected to be well tolerated without impacting TLR5 activation. However, attachment of GNE haptens to the remaining 10 lysine residues located in the highly conserved D0 and D1 domains might attenuate flagellin binding to TLR5. In particular, coupling of the large GNE hapten to K135, which is located within the D1 domain and forms a salt bridge to TLR5, could inhibit TLR5 binding. The results of our mTLR5 reporter assay (Figure 4) indicate that flagellin chemically modified with ∼7 GNE haptens per protein molecule binds to and activates TLR5. In our experiments, we observed that TLR5 activation is attenuated at higher hapten densities (i.e., above ∼10 GNE per flagellin). It may be possible to improve GNE-FliC by mutating select lysine residues in the D0 and D1 domains to arginine. For example, the K135R mutation in flagellin could protect the TLR5 binding interface against covalent modification with the bulky GNE hapten, thus potentially preserving the ability of the modified flagellin to activate TLR5 at even higher hapten densities.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of lysine residues in flagellin from Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Dublin bound to TLR5 (PDB 3V47(17a)). Flagellin is shown as a yellow ribbon with lysine side chains depicted as spheres colored by domain (subunit 1; D0, blue; D1, green; D2, magenta; D3, not shown) and wheat colored surface (subunit 2). Two TLR5 subunits are shown as light blue colored molecular surfaces. Inset table shows number of lysine residues in each domain.

Figure 4.

Flagellin (commercially available FLA-ST and our expressed FliC) and GNE-FliC conjugates (hapten densities in parentheses) tested at three different concentrations (100, 50, and 10 ng/mL) in an mTLR5 reporter assay. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, and error bars signify SEM.

Recombinant FliC showed roughly equivalent binding capabilities to positive control (FLA-ST), confirming the integrity of our expressed and purified flagellin protein. To ensure GNE-FliC conjugates still activate TLR5, prior to their inclusion in vaccine formulations for mice, we repeated the TLR5 reporter assay (Figure 4). Despite bearing a number of GNE haptens, modified flagellin protein still activates TLR5, although agonist function drops off as hapten density exceeds ∼10. Whereas TLR5 agonism is fully maintained using GNE-FliC with hapten density of ∼7, a marked reduction (∼65%) in agonism is observed when the hapten density is ∼15. Further reduction in agonism is observed with further increases in hapten density; e.g., flagellin’s ability to activate TLR5 is severely compromised when ∼24 GNE haptens per FliC are present. The decision to use a given lot of GNE-FliC in mouse immunization studies was guided by the following selection criteria: (a) Does it have sufficient GNE hapten density? (b) Does it still activate TLR5 expression? Using these mTLR5 assay results as a guide, we selected GNE-FliC with hapten densities of ∼7 for use in mouse immunizations.

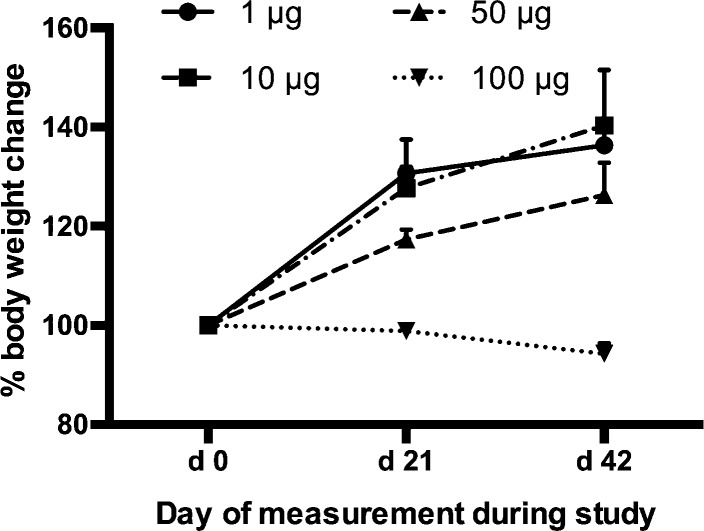

The dose-ranging component of our study of GNE-FliC in mice revealed that our standard hapten-protein dose of 100 μg per injection is not well tolerated when using flagellin protein. Each mouse received a dose of 100, 50, 10, or 1 μg GNE-FliC. The mice that received 100 μg of GNE-FliC exhibited weight loss, and the mice that received 50 μg of GNE-FliC exhibited attenuated weight gain, compared to the lower dose groups (Figure 5). It is known that high doses of flagellin (∼300 μg i.v.) induce septic shock, and even 10 μg i.p. induces inflammatory alterations characteristic of sepsis.40 It will be important to further evaluate lower doses of GNE-FliC in order to derive the adjuvant benefit while avoiding excessive pro-inflammatory cytokine stimulation.

Figure 5.

Body weight change over time course of study (n = 3–5 mice per group, error bars signify SEM).

Cytokine expression levels can be conveniently monitored via multiplex, bead-based assays, but the timing of analysis is critical. Typically, cytokine spikes are observed within 2–24 h following stimulus.41 However, in the present study, bleeds were collected and analyzed 7 days following boost injection. By this point, most cytokines had presumably resolved to near basal levels. Nevertheless, we did identify a dose–response trend in the case of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (Figure 6). TNFα (or cachectin) is produced by activated macrophages, is involved in systemic inflammation, and induces fever and cachexia.42 TNFα levels were higher in the 100 μg dose group than in the lower dose groups [dose: F3, 9 = 4.245, p < 0.05], and the overall trend correlates with our observations of body weight change in these mice. That is, an excess of GNE-FliC presumably elicits hyperinflammation, consequences of which are elevated TNFα levels (of prolonged duration) and inhibition of normal weight gain.43

Figure 6.

Levels of TNFα in mice for the dose-ranging aspect of this study (n = 3–5 mice per group, analyzed individually, error bars signify SEM). *p < 0.05 versus 1 and 10 μg groups (Fisher’s LSD posthoc).

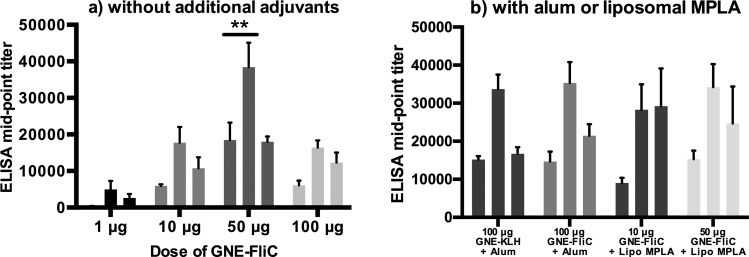

Although Simon et al. have reported protective responses with submicrogram doses of flagellin glycoconjugates,16d our data indicate that 1 μg of GNE-FliC is insufficient in eliciting a robust anticocaine antibody response (Figure 7a). This difference in dose effectiveness may be due to fundamental dissimilarities in the nature of the antigen (in their case, carbohydrate; in our case, cocaine hapten) as well as differences in the means by which protection against the respective threat is assessed. We did, however, observe modest to greatly improved titers with the other doses evaluated, with the best dose being 50 μg [bleed × dose interaction: F6, 20 = 4.10, p < 0.01]. In this case, anti-GNE antibody midpoint titers approached nearly 40,000 (bleed 2), which compares favorably with anti-GNE antibody titers we have previously measured (28,000 in one study and 31,000 in another).11 Alum-adjuvanted GNE-FliC produced similar anti-GNE titer levels to alum-adjuvanted GNE-KLH over the course of vaccination [time, F2, 24 = 30.08, p < 0.001; treatment, p > 0.05; Figure 7b]. Liposomal MPLA-adjuvanted GNE-FliC elicited anti-GNE titer levels that were similar to alum-adjuvanted GNE-FliC, although doses of conjugate were not equivalent.

Figure 7.

Anti-GNE IgG titers measured by ELISA (n = 3–5 mice per group, analyzed individually in duplicate, error bars signify SEM). Each trio of vertical bars represents bleeds 1, 2, and 3, respectively. **p < 0.05 versus all other doses at specific bleeds (Tukey’s posthoc).

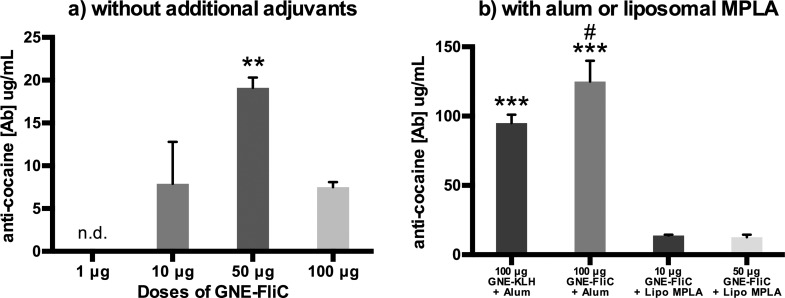

Anticocaine antibody concentrations and affinities (Kd values) were then measured by radioimmunoassay. The bell-shaped dose–response curve observed for anti-GNE antibody titers (Figure 7a) was likewise observed for anticocaine antibody concentrations (Figure 8a). Additionally, some other interesting findings were revealed. Despite exhibiting good anti-GNE titers (i.e., nearly 40,000 for the 50 μg dose), the corresponding anticocaine antibody concentrations are rather low (i.e., ∼20 μg/mL for the 50 μg dose) [dose: F3, 8 = 26.06, p < 0.001; Figure 8a]. By incorporating alum, a dramatic boost in anticocaine antibody concentration is achieved. In fact, alum-adjuvanted GNE-FliC elicited significantly higher anticocaine antibody concentrations than alum-adjuvanted GNE-KLH (Fisher’s LSD, p < 0.05). However, by incorporating liposomal MPLA, no boost in anticocaine antibody concentration is achieved [treatment: F3, 8 = 48.40, p < 0.001; Figure 8b]. Peak anti-GNE antibody titers, as well as anticocaine antibody concentrations and affinities, are also summarized in Table S1, Supporting Information.

Figure 8.

Anticocaine Ab concentrations and affinities measured by RIA (Bleed 3) (n = 3–5 mice per group, pooled and analyzed in triplicate, error bars signify SEM). **p < 0.01 versus all other doses; ***p < 0.001 versus MPLA groups (Tukey’s posthoc); #p < 0.05 versus KLH control (planned comparison Fisher’s LSD).

Discussion

Given the precedent for flagellin fusion proteins not needing additional adjuvants (e.g., STF2.OVA22a and STF2.4xM2e27d), we first focused our study on looking at various doses of GNE-FliC on its own. At the very basic level of analysis, GNE-FliC does indeed elicit anticocaine antibodies and does so in a dose-dependent fashion. Our data illustrate the oft-observed bell-shaped or inverted U-shaped dose–response curve. Indeed, we found that retreating from our standard dose of 100 μg of hapten-protein conjugate (per animal, per injection) was beneficial with respect to anti-GNE antibody titers and anticocaine antibody concentrations. It is worth noting that many studies using flagellin fusion proteins typically report optimal doses of 0.1 to 25 μg. In the dose-ranging component of our study, our best result was obtained using a 50 μg dose of GNE-FliC. It remains to be seen whether further fine-tuning of the dose can yield further gains in overall anticocaine antibody production. Nevertheless, it appears that maximal efficacy will be possible through the incorporation of additional adjuvants into the overall formulation, evidenced by our preliminary efforts in that regard.

We investigated two popular adjuvant formulation tactics: alum and liposomal MPLA. Flagellin itself induces a TH2 response, heavily favoring IgG1 production.16a,22a,44 Alum also induces a TH2 response,45 while MPLA inhibits TH2 response. Thus, a combination of flagellin and alum may be synergistic for TH2 induction, whereas a combination of flagellin and MPLA may be antagonistic.46 In our hands, s.c. alum/GNE-flagellin performed very well, markedly better than s.c. alum/GNE-KLH (anticocaine antibody concentrations of 125 and 95 μg/mL, respectively; Figure 8b). In previous work, we observed a similar level of anticocaine antibody production using i.p. SAS/GNE-KLH (123.47 μg/mL in one study11a and 85.12 μg/mL in another11b). It may be that the alum/GNE-FliC formulation permits activation of immune signaling via a variety of nonredundant pathways (TLR5/MyD88, NLRC4 inflammasome, phagolysosome/NLRP3), the combination of which ultimately provides robust antibody production.

Meanwhile, at the 50 μg dose of GNE-FliC, liposomal MPLA/GNE-FliC elicited comparable ELISA titers (Figure 7), but lower anticocaine antibody concentrations (Figure 8), than GNE-FliC alone (12.7 and 19.1 μg/mL, respectively). Thus, while a significant immunogenicity boost was realized through the use of alum (see above), no such boost was realized through the use of liposomal MPLA, at least, in the particular manner (i.e., method of formulation, route of administration) in which liposomal MPLA was used in this study. It should be noted that, although dual targeting of TLR4/TLR5 via liposomal MPLA/GNE-FliC was unproductive here, other combinations (e.g., TLR4/TLR8) are reportedly very effective.47

Conclusions

Our central aim was to determine whether one might use flagellin protein as both carrier and adjuvant. We have shown that cocaine-flagellin conjugates do indeed stimulate the production of anticocaine antibodies in mice, and this stimulation is dose-dependent. Furthermore, our initial ventures into incorporating other adjuvants (alum or liposomal MPLA) have suggested that significant gains can be achieved. Indeed, the alum/GNE-FliC formulation performed better than the alum/GNE-KLH formulation (Figure 8b). However, liposomal formulation of GNE-FliC elicited lower concentrations of anticocaine antibodies. It is known that some TLR agonist combinations are synergistic, while others are not.46 Thus, TLR4 agonism combined with TLR5 agonism may be counterproductive since the former inhibits TH2, while the latter induces TH2.

Future avenues of inquiry and optimization include investigating whether a CpG/Alum/GNE-FliC formulation (engaging endosomal TLR9, NLRP3, and TLR5/NLRC4 collectively) and/or an alternative injection route (e.g., i.m. instead of s.c.) will provide greater gains in anticocaine antibody production.48 Also, we wish to examine mutants of FliC in which specific lysine residues (particularly in the D0 and D1 domains) are replaced with arginine residues; this would serve the purpose of precluding hapten modification of these domains, which are known to be vital to TLR5 binding. The net effect of optimizing these vaccine parameters will undoubtedly be more potent production of anticocaine antibodies. Results of such endeavors will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank the TSRI Center for Mass Spectrometry and Metabolomics for performing MALDI-TOF MS, ESI-TOF MS, and MS/MS proteomics analyses. We thank TSRI Center for Antibody Production for performing preliminary mouse vaccinations and bleeds. We thank Jon A. Olson at Cal Poly Pomona for performing a Luminex assay. This is manuscript 28015 from The Scripps Research Institute. We acknowledge Amgen for a summer fellowship for J.C., the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA08590 to K.D.J.), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI042266 to I.A.W.) for financial support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Abs

antibodies

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CpG

cytosine-phosphate-guanine oligodeoxynucleotide

- DMPC

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DMPG

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol)

- DNP

2,4-dinitrophenyl

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ESI-TOF

electrospray ionization time-of-flight

- FliC

phase-1 flagellin C

- GNE

gold nugget E

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- MPLA

monophosphoryl lipid A

- NLR

NOD-like receptor

- pAbs

polyclonal antibodies

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- sulfo-NHS

N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide sodium salt

- TA-CD

cocaine vaccine consisting of succinylnorcocaine conjugated to inactivated cholera toxin B

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Supporting Information Available

SDS-PAGE gel image, representative ESI-TOF and MALDI-TOF MS spectra, MS/MS proteomics data, protein homology modeling parameters, and supplemental tables. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

† Department of Bioengineering, University of Washington, 3720 15th Avenue NE, Seattle, Washington 98195-5061, United States.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings; NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12–4713; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide, 3rd ed.; National Institute on Drug Abuse: Bethesda, MD, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- a Karila L.; Reynaud M.; Aubin H. J.; Rolland B.; Guardia D.; Cottencin O.; Benyamina A. Pharmacological treatments for cocaine dependence: is there something new?. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17141359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Loftis J. M.; Huckans M. Substance use disorders: Psychoneuroimmunological mechanisms and new targets for therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 1392289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell L. L.; Nye J. A.; Stehouwer J. S.; Voll R. J.; Mun J.; Narasimhan D.; Nichols J.; Sunahara R.; Goodman M. M.; Carroll F. I.; Woods J. H. A thermostable bacterial cocaine esterase rapidly eliminates cocaine from brain in nonhuman primates. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Haney M.; Gunderson E. W.; Jiang H.; Collins E. D.; Foltin R. W. Cocaine-specific antibodies blunt the subjective effects of smoked cocaine in humans. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67159–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shen X. Y.; Orson F. M.; Kosten T. R. Vaccines against drug abuse. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 91160–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G.; Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988, 85145274–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treweek J. B.; Roberts A. J.; Janda K. D. Immunopharmacotherapeutic manifolds and modulation of cocaine overdose. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2011, 983474–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell B. A.; Mitchell E.; Poling J.; Gonsai K.; Kosten T. R. Vaccine pharmacotherapy for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 582158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell B. A.; Orson F. M.; Poling J.; Mitchell E.; Rossen R. D.; Gardner T.; Kosten T. R. Cocaine vaccine for the treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-maintained patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66101116–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Brimijoin S.; Shen X.; Orson F.; Kosten T. Prospects, promise and problems on the road to effective vaccines and related therapies for substance abuse. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2013, 123323–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kosten T.; Domingo C.; Orson F.; Kinsey B. Vaccines against stimulants: cocaine and MA. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 772368–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Orson F. M.; Wang R.; Brimijoin S.; Kinsey B. M.; Singh R. A.; Ramakrishnan M.; Wang H. Y.; Kosten T. R. The future potential for cocaine vaccines. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2014, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cai X.; Whitfield T.; Moreno A. Y.; Grant Y.; Hixon M. S.; Koob G. F.; Janda K. D. Probing the effects of hapten stability on cocaine vaccine immunogenicity. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10114176–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cai X.; Whitfield T.; Hixon M. S.; Grant Y.; Koob G. F.; Janda K. D. Probing active cocaine vaccination performance through catalytic and noncatalytic hapten design. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 5693701–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrafnkelsdottir K.; Valgeirsson J.; Gizurarson S. Induction of protective and specific antibodies against cocaine by intranasal immunisation using a glyceride adjuvant. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 2861038–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliyannis G.; Kedzierska K.; Lau Y. F.; Zeng W.; Turner S. J.; Jackson D. C.; Brown L. E. Intranasal lipopeptide primes lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells for long-term pulmonary protection against influenza. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 363770–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a O’Neill L. A.; Bryant C. E.; Doyle S. L. Therapeutic targeting of Toll-like receptors for infectious and inflammatory diseases and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009, 612177–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ingale S.; Wolfert M. A.; Buskas T.; Boons G. J. Increasing the antigenicity of synthetic tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens by targeting Toll-like receptors. ChemBioChem 2009, 103455–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hennessy E. J.; Parker A. E.; O’Neill L. A. Targeting Toll-like receptors: emerging therapeutics?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 94293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Duthie M. S.; Windish H. P.; Fox C. B.; Reed S. G. Use of defined TLR ligands as adjuvants within human vaccines. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 239, 178–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Olive C. Pattern recognition receptors: sentinels in innate immunity and targets of new vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2012, 112237–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaude J.; Kent A.; van Rooijen N.; Blander J. M. Simultaneous targeting of toll- and nod-like receptors induces effective tumor-specific immune responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4120120ra16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Minami M.; Usui M.; Kanno T.; Tamura N.; Matuhasi T. Demonstration of two types of helper T cells for different IgG subclass responses to dinitrophenylated flagellin polymer. J. Immunol. 1978, 12041195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Campodonico V. L.; Llosa N. J.; Bentancor L. V.; Maira-Litran T.; Pier G. B. Efficacy of a conjugate vaccine containing polymannuronic acid and flagellin against experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 2011, 7983455–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Simon R.; Tennant S. M.; Wang J. Y.; Schmidlein P. J.; Lees A.; Ernst R. K.; Pasetti M. F.; Galen J. E.; Levine M. M. Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis core O polysaccharide conjugated to H:g,m flagellin as a candidate vaccine for protection against invasive infection with S. enteritidis. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79104240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Simon R.; Wang J. Y.; Boyd M. A.; Tulapurkar M. E.; Ramachandran G.; Tennant S. M.; Pasetti M.; Galen J. E.; Levine M. M. Sustained protection in mice immunized with fractional doses of Salmonella enteritidis core and O polysaccharide-flagellin glycoconjugates. PLoS One 2013, 85e64680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yoon S. I.; Kurnasov O.; Natarajan V.; Hong M.; Gudkov A. V.; Osterman A. L.; Wilson I. A. Structural basis of TLR5-flagellin recognition and signaling. Science 2012, 3356070859–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bates J. T.; Uematsu S.; Akira S.; Mizel S. B. Direct stimulation of tlr5+/+ CD11c+ cells is necessary for the adjuvant activity of flagellin. J. Immunol. 2009, 182127539–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hayashi F.; Smith K. D.; Ozinsky A.; Hawn T. R.; Yi E. C.; Goodlett D. R.; Eng J. K.; Akira S.; Underhill D. M.; Aderem A. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature 2001, 41068321099–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSorley S. J.; Ehst B. D.; Yu Y.; Gewirtz A. T. Bacterial flagellin is an effective adjuvant for CD4+ T cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 2002, 16973914–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didierlaurent A.; Ferrero I.; Otten L. A.; Dubois B.; Reinhardt M.; Carlsen H.; Blomhoff R.; Akira S.; Kraehenbuhl J. P.; Sirard J. C. Flagellin promotes myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent development of Th2-type response. J. Immunol. 2004, 172116922–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Vijay-Kumar M.; Carvalho F. A.; Aitken J. D.; Fifadara N. H.; Gewirtz A. T. TLR5 or NLRC4 is necessary and sufficient for promotion of humoral immunity by flagellin. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010, 40123528–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhao Y.; Yang J.; Shi J.; Gong Y. N.; Lu Q.; Xu H.; Liu L.; Shao F. The NLRC4 inflammasome receptors for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion apparatus. Nature 2011, 4777366596–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Yglesias A. H.; Zhao X.; Quarles E. K.; Lai M. A.; VandenBos T.; Strong R. K.; Smith K. D. Flagellin induces antibody responses through a TLR5- and inflammasome-independent pathway. J. Immunol. 2014, 19241587–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huleatt J. W.; Jacobs A. R.; Tang J.; Desai P.; Kopp E. B.; Huang Y.; Song L.; Nakaar V.; Powell T. J. Vaccination with recombinant fusion proteins incorporating Toll-like receptor ligands induces rapid cellular and humoral immunity. Vaccine 2007, 254763–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Terron-Exposito R.; Dudognon B.; Galindo I.; Quetglas J. I.; Coll J. M.; Escribano J. M.; Gomez-Casado E. Antibodies against Marinobacter algicola and Salmonella typhimurium flagellins do not cross-neutralize TLR5 activation. PLoS One 2012, 711e48466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Vijay-Kumar M.; Aitken J. D.; Sanders C. J.; Frias A.; Sloane V. M.; Xu J.; Neish A. S.; Rojas M.; Gewirtz A. T. Flagellin treatment protects against chemicals, bacteria, viruses, and radiation. J. Immunol. 2008, 180128280–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mizel S. B.; Bates J. T. Flagellin as an adjuvant: cellular mechanisms and potential. J. Immunol. 2010, 185105677–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cuadros C.; Lopez-Hernandez F. J.; Dominguez A. L.; McClelland M.; Lustgarten J. Flagellin fusion proteins as adjuvants or vaccines induce specific immune responses. Infect. Immun. 2004, 7252810–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose C.; Verhagen J. M.; Chen X.; Yu J.; Huang Y.; Chenesseau O.; Kelly C. P.; Ho D. D. Toll-like receptor 5-dependent immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a recombinant fusion protein vaccine containing the nontoxic domains of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B and Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium flagellin in a mouse model of Clostridium difficile disease. Infect. Immun. 2013, 8162190–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Weimer E. T.; Lu H.; Kock N. D.; Wozniak D. J.; Mizel S. B. A fusion protein vaccine containing OprF epitope 8, OprI, and type A and B flagellins promotes enhanced clearance of nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 2009, 7762356–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Weimer E. T.; Ervin S. E.; Wozniak D. J.; Mizel S. B. Immunization of young African green monkeys with OprF epitope 8-OprI-type A- and B-flagellin fusion proteins promotes the production of protective antibodies against nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Vaccine 2009, 27486762–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Honko A. N.; Sriranganathan N.; Lees C. J.; Mizel S. B. Flagellin is an effective adjuvant for immunization against lethal respiratory challenge with Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 2006, 7421113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mizel S. B.; Graff A. H.; Sriranganathan N.; Ervin S.; Lees C. J.; Lively M. O.; Hantgan R. R.; Thomas M. J.; Wood J.; Bell B. Flagellin-F1-V fusion protein is an effective plague vaccine in mice and two species of nonhuman primates. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009, 16121–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Treanor J. J.; Taylor D. N.; Tussey L.; Hay C.; Nolan C.; Fitzgerald T.; Liu G.; Kavita U.; Song L.; Dark I.; Shaw A. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant hemagglutinin influenza-flagellin fusion vaccine (VAX125) in healthy young adults. Vaccine 2010, 28528268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Leng J.; Stout-Delgado H. W.; Kavita U.; Jacobs A.; Tang J.; Du W.; Tussey L.; Goldstein D. R. Efficacy of a vaccine that links viral epitopes to flagellin in protecting aged mice from influenza viral infection. Vaccine 2011, 29458147–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liu G.; Tarbet B.; Song L.; Reiserova L.; Weaver B.; Chen Y.; Li H.; Hou F.; Liu X.; Parent J.; Umlauf S.; Shaw A.; Tussey L. Immunogenicity and efficacy of flagellin-fused vaccine candidates targeting 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza in mice. PLoS One 2011, 66e20928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Turley C. B.; Rupp R. E.; Johnson C.; Taylor D. N.; Wolfson J.; Tussey L.; Kavita U.; Stanberry L.; Shaw A. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant M2e-flagellin influenza vaccine (STF2.4xM2e) in healthy adults. Vaccine 2011, 29325145–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Liu G.; Song L.; Reiserova L.; Trivedi U.; Li H.; Liu X.; Noah D.; Hou F.; Weaver B.; Tussey L. Flagellin-HA vaccines protect ferrets and mice against H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) infections. Vaccine 2012, 30486833–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Taylor D. N.; Treanor J. J.; Sheldon E. A.; Johnson C.; Umlauf S.; Song L.; Kavita U.; Liu G.; Tussey L.; Ozer K.; Hofstaetter T.; Shaw A. Development of VAX128, a recombinant hemagglutinin (HA) influenza-flagellin fusion vaccine with improved safety and immune response. Vaccine 2012, 30395761–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Huleatt J. W.; Nakaar V.; Desai P.; Huang Y.; Hewitt D.; Jacobs A.; Tang J.; McDonald W.; Song L.; Evans R. K.; Umlauf S.; Tussey L.; Powell T. J. Potent immunogenicity and efficacy of a universal influenza vaccine candidate comprising a recombinant fusion protein linking influenza M2e to the TLR5 ligand flagellin. Vaccine 2008, 262201–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney K. N.; Phipps J. P.; Johnson J. B.; Mizel S. B. A recombinant flagellin-poxvirus fusion protein vaccine elicits complement-dependent protection against respiratory challenge with vaccinia virus in mice. Viral Immunol. 2010, 232201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald W. F.; Huleatt J. W.; Foellmer H. G.; Hewitt D.; Tang J.; Desai P.; Price A.; Jacobs A.; Takahashi V. N.; Huang Y.; Nakaar V.; Alexopoulou L.; Fikrig E.; Powell T. J. A West Nile virus recombinant protein vaccine that coactivates innate and adaptive immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 195111607–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. N.; Treanor J. J.; Strout C.; Johnson C.; Fitzgerald T.; Kavita U.; Ozer K.; Tussey L.; Shaw A. Induction of a potent immune response in the elderly using the TLR-5 agonist, flagellin, with a recombinant hemagglutinin influenza-flagellin fusion vaccine (VAX125, STF2.HA1 SI). Vaccine 2011, 29314897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Shima F.; Uto T.; Akagi T.; Akashi M. Synergistic Stimulation of Antigen Presenting Cells via TLR by Combining CpG ODN and Poly(γ-glutamic acid)-Based Nanoparticles as Vaccine Adjuvants. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 246926–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Primard C.; Poecheim J.; Heuking S.; Sublet E.; Esmaeili F.; Borchard G. Multifunctional PLGA-Based Nanoparticles Encapsulating Simultaneously Hydrophilic Antigen and Hydrophobic Immunomodulator for Mucosal Immunization. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 1082996–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Peine K. J.; Bachelder E. M.; Vangundy Z.; Papenfuss T.; Brackman D. J.; Gallovic M. D.; Schully K.; Pesce J.; Keane-Myers A.; Ainslie K. M. Efficient Delivery of the Toll-like Receptor Agonists Polyinosinic:Polycytidylic Acid and CpG to Macrophages by Acetalated Dextran Microparticles. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 1082849–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Fujita Y.; Taguchi H. Overview and outlook of Toll-like receptor ligand-antigen conjugate vaccines. Ther. Delivery 2012, 36749–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Moyle P. M.; Toth I. Modern subunit vaccines: development, components, and research opportunities. ChemMedChem 2013, 83360–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott P. F.; Ciacci-Woolwine F.; Snipes J. A.; Mizel S. B. High-affinity interaction between gram-negative flagellin and a cell surface polypeptide results in human monocyte activation. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68105525–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Aida Y.; Pabst M. J. Removal of endotoxin from protein solutions by phase separation using Triton X-114. J. Immunol. Methods 1990, 1322191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Krag D. N.; Fuller S. P.; Oligino L.; Pero S. C.; Weaver D. L.; Soden A. L.; Hebert C.; Mills S.; Liu C.; Peterson D. Phage-displayed random peptide libraries in mice: toxicity after serial panning. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2002, 504325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Koob G.; Hicks M. J.; Wee S.; Rosenberg J. B.; De B. P.; Kaminsky S. M.; Moreno A.; Janda K. D.; Crystal R. G. Anti-cocaine vaccine based on coupling a cocaine analog to a disrupted adenovirus. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2011, 108899–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wee S.; Hicks M. J.; De B. P.; Rosenberg J. B.; Moreno A. Y.; Kaminsky S. M.; Janda K. D.; Crystal R. G.; Koob G. F. Novel cocaine vaccine linked to a disrupted adenovirus gene transfer vector blocks cocaine psychostimulant and reinforcing effects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 3751083–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c De B. P.; Pagovich O. E.; Hicks M. J.; Rosenberg J. B.; Moreno A. Y.; Janda K. D.; Koob G. F.; Worgall S.; Kaminsky S. M.; Sondhi D.; Crystal R. G. Disrupted adenovirus-based vaccines against small addictive molecules circumvent anti-adenovirus immunity. Hum. Gene Ther. 2013, 24158–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Maoz A.; Hicks M. J.; Vallabhjosula S.; Synan M.; Kothari P. J.; Dyke J. P.; Ballon D. J.; Kaminsky S. M.; De B. P.; Rosenberg J. B.; Martinez D.; Koob G. F.; Janda K. D.; Crystal R. G. Adenovirus capsid-based anti-cocaine vaccine prevents cocaine from binding to the nonhuman primate CNS dopamine transporter. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38112170–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A.; Blundell T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993, 2343779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki-Yonekura S.; Yonekura K.; Namba K. Conformational change of flagellin for polymorphic supercoiling of the flagellar filament. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 174417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyas G. R.; Muderhwa J. M.; Alving C. R. Oil-in-water liposomal emulsions for vaccine delivery. Methods Enzymol. 2003, 373, 34–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lu Y.; Welsh J. P.; Chan W.; Swartz J. R. Escherichia coli-based cell free production of flagellin and ordered flagellin display on virus-like particles. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 11082073–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Samatey F. A.; Imada K.; Vonderviszt F.; Shirakihara Y.; Namba K. Crystallization of the F41 fragment of flagellin and data collection from extremely thin crystals. J. Struct. Biol. 2000, 1322106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen A.; Kennedy S. W. A fluorescence-based protein assay for use with a microplate reader. Anal. Biochem. 1993, 2141346–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves-Pyles T.; Murthy K.; Liaudet L.; Virag L.; Ross G.; Soriano F. G.; Szabo C.; Salzman A. L. Flagellin, a novel mediator of Salmonella-induced epithelial activation and systemic inflammation: IκBα degradation, induction of nitric oxide synthase, induction of proinflammatory mediators, and cardiovascular dysfunction. J. Immunol. 2001, 16621248–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaudet L.; Murthy K. G.; Mabley J. G.; Pacher P.; Soriano F. G.; Salzman A. L.; Szabo C. Comparison of inflammation, organ damage, and oxidant stress induced by Salmonella enterica serovar Muenchen flagellin and serovar Enteritidis lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 2002, 701192–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B.; Greenwald D.; Hulmes J. D.; Chang M.; Pan Y. C.; Mathison J.; Ulevitch R.; Cerami A. Identity of tumour necrosis factor and the macrophage-secreted factor cachectin. Nature 1985, 3166028552–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey K. J.; Cerami A. Metabolic responses to cachectin/TNF. A brief review. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1990, 587, 325–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobat S.; Flores-Langarica A.; Hitchcock J.; Marshall J. L.; Kingsley R. A.; Goodall M.; Gil-Cruz C.; Serre K.; Leyton D. L.; Letran S. E.; Gaspal F.; Chester R.; Chamberlain J. L.; Dougan G.; Lopez-Macias C.; Henderson I. R.; Alexander J.; MacLennan I. C.; Cunningham A. F. Soluble flagellin, FliC, induces an Ag-specific Th2 response, yet promotes T-bet-regulated Th1 clearance of Salmonella typhimurium infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 4161606–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grun J. L.; Maurer P. H. Different T helper cell subsets elicited in mice utilizing two different adjuvant vehicles: the role of endogenous interleukin 1 in proliferative responses. Cell. Immunol. 1989, 1211134–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh T. K.; Mickelson D. J.; Solberg J. C.; Lipson K. E.; Inglefield J. R.; Alkan S. S. TLR-TLR cross talk in human PBMC resulting in synergistic and antagonistic regulation of type-1 and 2 interferons, IL-12 and TNF-α. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007, 781111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling D. J.; Tan Z.; Prokopowicz Z. M.; Palmer C. D.; Matthews M. A.; Dietsch G. N.; Hershberg R. M.; Levy O. The ultra-potent and selective TLR8 agonist VTX-294 activates human newborn and adult leukocytes. PLoS One 2013, 83e58164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer P. T.; Schlosburg J. E.; Lively J. M.; Janda K. D. Injection route and TLR9 agonist addition significantly impact heroin vaccine efficacy. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2014, 1131075–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.