Abstract

Age and portion size have been found to influence food intake in American children but have not been examined in an international context. This study evaluated the association between age and the effects of portion size on the food intake of kindergarteners in Kunming, China. Using a within-subjects crossover design in a classroom setting, 173 children in two age groups, mean age 4.2 years and 6.1 years, were served a predefined reference, small (-30%) and large (+30%) portion of rice, vegetables, and a protein source during lunchtime over three consecutive days. Each portion was weighed before and after the meal to determine amount of food consumed. Linear mixed modeling, controlling for repeated measures and clustering by classroom, was used to compare food intake under small and large portion size conditions to the reference portion. Children ate significantly less food when served small portions. When served a large portion, 6-year-old children increased food intake while 4-year-old children decreased food intake in comparison to the reference portion. Findings indicate that portion size affects food intake in Chinese children 4- to 6-years old. Older children show larger increases in food intake with increased portion size than do younger children.

Keywords: Portion size, children, China, dietary intake, preschool, kindergarten, obesity

Introduction

In developed countries, portion size has been recognized as an important contributor to the obesogenic environment (Young & Nestle, 2002), with portion sizes increasing in the United States and Europe over recent decades (Matthiessen, Fagt, Biltoft-Jensen, Beck, & Ovesen, 2003; Nielsen & Popkin, 2003; Piernas & Popkin, 2011; Smiciklas-Wright, Mitchell, Mickle, Goldman, & Cook, 2003; Steenhuis, Leeuwis, & Vermeer, 2010; Young & Nestle, 2002). Increased portion size leads to higher overall daily food intake, promoting weight gain (Rolls, Roe, & Meengs, 2006). Studies in the US have shown that while toddlers and infants eat primarily in response to physiological cues of hunger and satiety (Dewey & Lönnerdal, 2008; Shea, Stein, Basch, Contento, & Zybert, 1992) and are capable of energy self-regulation across meals and days (Cecil et al., 2005; Fox, Devaney, Reidy, Razafindrakoto, & Ziegler, 2006), as children get older they increasingly eat in response to a variety of environmental and social cues, including portion size (Birch & Fisher, 1998; Fisher & Kral, 2008). Data from US national surveys shows that portion size accounts for 17-19% of the variability in food intake for 2- to 5-year-old children (Fox et al., 2006). A large body of evidence from controlled feeding studies in the US has demonstrated that portion size influences the eating behavior of pre-school age children (Fisher, 2007; Fisher, Arreola, Birch, & Rolls, 2007; Fisher & Kral, 2008; Fisher, Liu, Birch, & Rolls, 2007; Rolls, Engell, & Birch, 2000), with larger portions increasing food intake. Taken together, these studies suggest that while young children respond primarily to hunger and satiety, there is some point in the development process when children begin to respond to contextual cues such as portion size.

However, most of the work examining portion size and food intake in children has been done in the US, and it is unclear whether children in other countries demonstrate a similar shift in responsiveness to portion size as they age. We might expect that children's response to portion size would vary in other regions of the world, considering that eating behavior—and the influence of portion size on eating behavior— may be influenced by cultural norms, social cues, food availability, and other contextual factors (Galloway, Fiorito, Francis, & Birch, 2006; Geier, Rozin, & Doros, 2006; Story, Neumark-Sztainer, & French, 2002). Understanding how portion size affects child food intake in different populations will become increasingly important as public health efforts aimed at stemming the childhood obesity epidemic flourish and take hold in regions around the globe.

China provides an ideal setting for further exploration of this question. In China, the nutrition transition is well underway, characterized by shifts towards increasingly Westernized diet patterns, declines in physical activity (Du, Lu, Zhai, & Popkin, 2002; Popkin, 2001; Wang, Mi, Shan, Wang, & Ge, 2006; Wu et al., 2005) and the marked increase of childhood overweight and obesity (Cui, Huxley, Wu, & Dibley, 2010; Ding, 2008; Ji, Sun, & Chen, 2004). These shifts in the way children eat, move, and live make China an important location for further investigation of the effect of portion size on children's food consumption. Currently, it is unknown whether Chinese children respond to larger portions by increasing food intake, similar to children in the US, or if they are less susceptible to the effects of portion size.

Another important unanswered question regards the age at which children become more sensitive to portion size cues, with studies providing conflicting results regarding the association between age, portion size, and food intake (Fisher & Kral, 2008). Rolls' study of 3- to 5-year-old American children found that a larger portion of a macaroni and cheese entrée increased intake of the entrée by 60% amongst 5-year old children but had no effect on the intake of 3-year old children, suggesting a developmental change in response to portion size cues during this period (Rolls et al., 2000). However, a subsequent meal-based study found that doubling an entrée increased intake of that entrée by 25% amongst 3- to 6- year old children, but that age was unassociated with the effects of portion size on children's entrée intake (Fisher, Rolls, & Birch, 2003). A third experimental study examining portion size in a group of 2- to 9-year old children found no significant association between age and the effects of portion size, with children increasing entrée consumption when served a larger portion size across all ages (Fisher, 2007). Although laboratory studies have found that increased portion size increases food intake in children as young as two years old, a question remains as to whether the magnitude of the effect of increased portion size is similar between older and younger children. Similarly, further work is needed to examine whether this effect appears in real-life settings such as a school classroom.

This repeated measures cross-over study seeks to add to previous research by extending work on portion size and food intake to Chinese children consuming a meal in their typical lunchtime environment. The objective of this study is to evaluate the association between age and the effects of portion size on food intake in Chinese children in a field-based setting. The primary hypotheses were that children would consume 1) less food when given small portions, 2) more food when presented with large portions, and 3) that age would modify the effects of portion size on consumption, such that older children would consume relatively more as a result of increased portion size compared to younger children.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted at DaGuan Kindergarten in Kunming, Yunnan Province, China. The school was selected due to its participation in a previous nutrition education intervention program, relationships with research staff at Kunming Medical University, and the school administration's interest in the study.

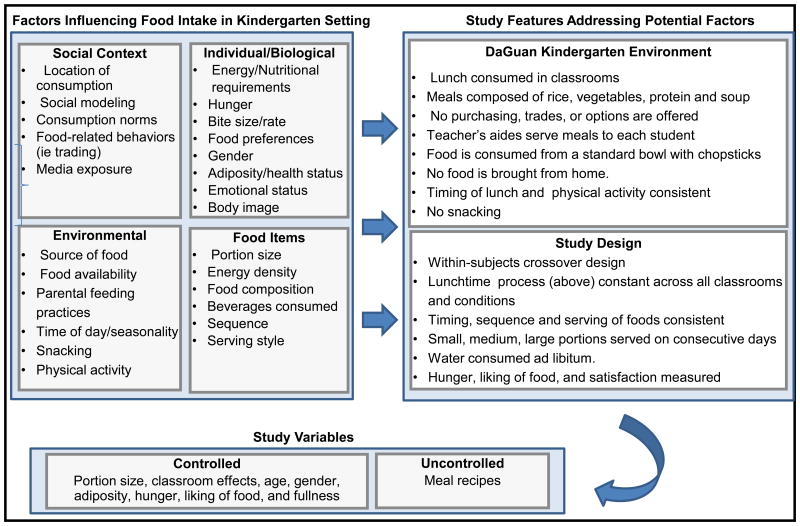

Like most kindergartens in China, DaGuan kindergarten provides a full day program (8:00am to 5:00pm) that delivers education and child care to children between the ages of three and six years (China Education and Research Network, 2001). This kindergarten provided a strong setting for examining age-related effects of portion size on food intake because the structure of the students' schedule naturally limits variation in a number of factors hypothesized to influence food consumption (Figure 1) (Addessi, Galloway, Visalberghi, & Birch, 2005; Booth et al., 2001; Fisher et al., 2003; Torun, 2005; Brian Wansink, 2004). Children are not permitted to snack prior to lunch, nor do any students bring lunches from home. Each day, the school provides a lunch-time meal, which is comprised of two parts: a mix and a soup. The mix contains rice (50%), vegetables (25%), and a protein source (25%), either meat or tofu; the soup is a meat-based broth. In each classroom, teacher's aides dish portions of the mix and serve the children. The students eat at their assigned classroom seat at a table of five to seven other students. Children use bowls and chopsticks to consume the food, and little to no trading of food items occurs. Children are allowed to ask for additional portions once they have eaten the previous portion. Children do not pay for lunch or for additional portions. The lunch period lasts approximately 15 minutes and is followed by a resting period. During the study, portions were weighed outside the classroom so as to avoid introducing a change to the lunchtime environment. Careful maintenance of the lunchtime routine created a consistent environment between classrooms and across study days, enabling observation of the effects of portion size similar to what would occur in a natural setting while restricting variation in other external factors that influence food intake. In other words, children consumed typical food in their typical lunchtime setting amongst their friends and teachers; the only change to their mealtime routine was portion size of foods served.

Figure 1. Factors affecting food intake in a school-based setting and features of the DaGuan portion size study design.

Participant Recruitment

Participants in this study were members of the four youngest (i.e. 4-year-old) and four oldest (i.e. 6-year-old) classes at DaGuan Kindergarten in Kunming. Children were recruited into the study based on their enrollment in one of the eight classes (n=266). Parents read, signed, and returned a consent form prior to their child's participation in this study (n=250). One child was excluded for being under age 3, and all children who attended school on all three study days were included in the analysis (n=172). The high attrition rate was due to the level of absenteeism in the kindergarten, not to children dropping out of the study. All procedures were approved by the Human Investigations Committee and Pediatric Protocol Review Committee at Yale University and Kunming Medical University.

Procedure

The size of typical, age-appropriate portions to be used in the study was determined during a pilot study conducted in a randomly selected 4-year-old classroom and randomly selected 6-year-old classroom. Each student's servings of the mix and soup served during the pilot lunch were weighed, recorded, and used to determine the average portion size of each meal component for each age group. The average portion size for each age group was then calculated and considered as the reference portion size during the actual experiment.

Each student was served either a small, reference, or large portion of the mix (rice/vegetable/protein) and soup each day at lunchtime for three consecutive days. In order to control for classroom effects, the order of portion size conditions was randomized at the age-group level, with all children in the same age group receiving the same portion size condition. Consistent with previous food regulation studies in children (Rolls et al., 2000), small and large portion sizes were 30% lighter and 30% heavier than the reference portion size, respectively. The 4-year-old age group was offered portions of 105 g, 150 g, and 195 g (+/- 10 g) of the rice/vegetable/protein mix, and the 6-year-old age group was served 182 g, 261 g, and 389 g (+/- 10 g) respectively. All portions were served in the same size bowl.

Children were allowed as many portions as they liked and had access to as much drinking water as they wanted during the meals. Children completed questionnaires before and after meals to assess hunger, fullness, and how much they liked the food (Roberto, Baik, Harris, & Brownell, 2010; Rolls et al., 2000).

Measures

Anthropometrics

Height and weight measurements were taken by trained research staff using a portable stadiometer and digital scale (World Health Organization, 2011). Heavy clothing and shoes were removed, and measurements were taken to the nearest centimeter (height) and gram (weight). Weight and height values were converted into BMI- z-scores adjusted for gender and age using child growth standards from the World Health Organization (WHO Anthro version 3.2.2, January 2011).

Food intake

Bowls presented to participants were weighed using calibrated digital scales to the nearest tenth of a gram, and weighed again after each portion was consumed. Food intake was calculated by subtracting the weight of the bowl after the meal from the starting weight. Percent change in food intake for each portion (small, reference, large) was calculated by dividing the amount consumed during each portion condition by the amount consumed during the reference portion condition.

Hunger, Fullness, and Liking of Food

A questionnaire to measure hunger was completed prior to serving the meal, and an additional questionnaire to measure fullness and liking of the food was conducted after the meal was finished and all food removed (Appendix A). The questions regarding hunger and fullness consisted of text and cartoon figures of shaded stomachs to provide visual depictions of a 3-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” (hungry/full) to “very” (hungry/full). The question about how much the child liked the food consisted of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “love it” to “hate it” with smiley faces used to depict facial expressions (Birch, 1979; Birch, Zimmerman, & Hind, 1980; Rolls et al., 2000). In younger classrooms, teacher's aides provided assistance to younger children by pointing to each smiley face and asking each child to verbally indicate which smiley face best represented how much they liked the meal.

Statistical Analysis

A linear mixed model with random intercept was developed using SPSS (MIXED) to control for repeated measures at the individual level and clustering by classroom. Percent change in food intake from the reference portion was the dependent variable, allowing each individual to be their own control, and allowing comparison of the change in intake across the age groups. The within-subjects factor was portion size and the between subjects factor was age group. Covariates included gender, BMI-for-age z-score, hunger, fullness, and liking of food. Cohen's f2 was calculated to obtain local effect sizes for each covariate in the multivariate mixed-effects regression model (Selya, Rose, Dierker, Hedeker, & Mermelstein, 2012). Estimated marginal means were used to predict the average change in food intake for age groups at each portion size, controlling for covariates. All data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 20.0.0, 2011, IBM).

Results

Participant Characteristics

266 students were recruited into this study based on their enrollment in the four youngest and four oldest classes at DaGuan elementary school, with 250 students agreeing to participate (94%). The analysis included children who participated in all three portion size conditions and who were at least 3 years of age (n=171) (69%). Characteristics of the sample population are presented in Table 1. The 4-year-old age group (n=94) was larger and had more girls (n=49), while the 6-year-old age group (n=77) had more boys (n=48). The smaller sample size in the older group is a result of one group of students whose parents declined to complete the informed consent.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of 4- to 6- year old children in DaGuan Kindergarten (n=171).

| 4-year old age group (n=94) |

6-year-old age group (n=77) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

|

|

|||||

| Age | 4.1 | .36 | 6.1 | .24 | |

| BMI-for-age z-score | -0.2 | .86 | -0.1 | -1.1 | |

| Portion size | |||||

| Small | 179a | 73 | 252a,b,c | 118 | |

| Reference | 256 | 75 | 325c | 118 | |

| Large | 183a | 76 | 441ac | 193 | |

Mean food intake was significantly different than the reference portion, using t-test p ≤ 0.01

Mean food intake was significantly different than the large portion, using t-test p ≤ 0.01

Mean food intake within portion size and between age group was significantly different, using t-test p ≤ 0.01

Analysis within Age Groups

The 4-year-old age group ate 179 g (±73 g) when given the small portion (24% less than reference) and 183 g (± 76 g) when presented with the large portion (24% less than reference) (Table 1). The 4-year-olds consumed significantly more food when served the reference portion (256 g ± 75 g) (p < 0.01). The 6-year-old age group ate significantly more with each increase in portion size: they consumed 252 g (± 118 g) when presented with small portions (18% less than reference), 325 g (± 118 g) when served the reference portion, and 441 g (± 193g) when given large portions (43% less than reference) (p<0.01).

Children were permitted to eat ad libitum in each condition: 49% of children asked for additional portions when presented with the small portion, 60% asked for additional portions in the medium condition, and 26% asked for additional portions in the large condition.

Hunger, Liking and Fullness

Hunger varied across the study conditions for the six year-old age group, with more children reporting being very hungry before being served the large portion (p<0.05) (data not shown). Hunger did not vary by portion size for the 4-year-old age group. Liking varied somewhat for both age groups (data not shown), although the difference was only significant in the 6-year-old age group (p<0.01). More of the 6-year-old age group reported that they were ambivalent or didn't like the food under the reference portion size (data not shown). Fullness did not vary for either age group (data not shown). Because of the variation in hunger and children's liking of the meal across age groups and portion sizes, both variables were controlled for in the final model.

Interaction of age and portion size on food intake

After adjusting for sex, hunger, liking, and the interaction between liking, portion size and age group, portion size was significantly associated with change in food intake, yielding an effect size of 0.502 (p<0.001) (Table 2). Age group was also associated with a change in food intake (p<0.001), and there was a significant interaction of age with the effect of portion size (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Effect sizes for portion size, age group, and liking of food from a mixed-effects regression model*.

| Predictor | Effect Size (Cohen's f2) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group | .047 | <0.001 |

| Portion Size | .502 | <0.001 |

| Liking | .047 | 0.006 |

| Age group*portion size | .281 | <0.001 |

| Liking*portion size | .034 | 0.001 |

| Liking*age group | .012 | 0.606 |

| Age group*portion size * liking | .011 | 0.042 |

|

| ||

| Full model R2 | 0.353 | |

Adjusted for hunger and gender

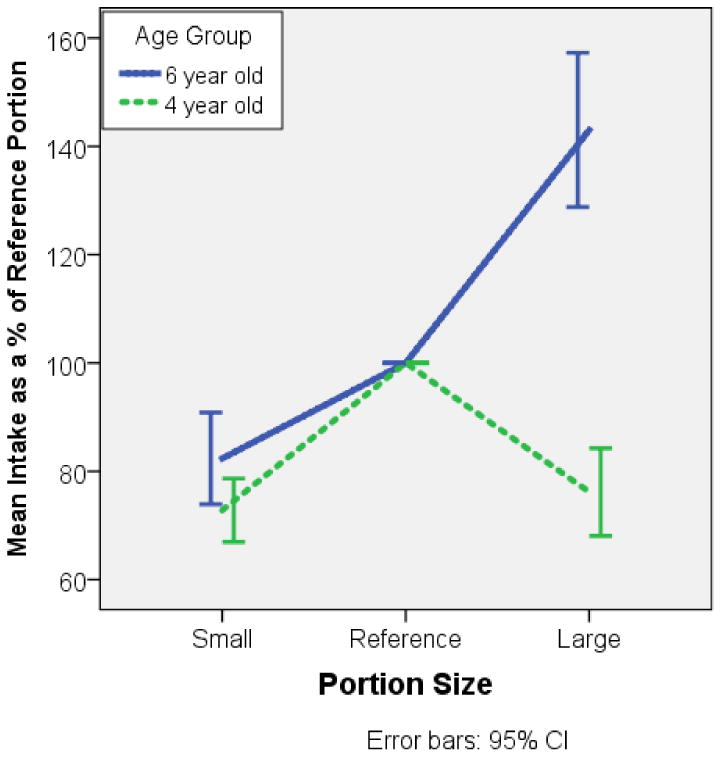

The estimated marginal means, which are the predicted means of change in food intake for each portion size after controlling for group-level differences in gender, hunger and liking, were significantly different between the two age groups for the large portion sizes (p<0.01) and marginally different between the two age groups for the small portion sizes (p=0.066) (Figure 2). The effect of portion size on food intake varies by age group after controlling for other key covariates: when presented with smaller portion sizes, 4-year-olds consume 29.6% less than when they are offered the reference condition, while 6-year-olds consume 15.8% less when presented with a small portion compared to the reference condition (p=0.060). When presented with large portions, 4-year-olds consume 29.5% less food compared to the reference portion, while 6-year-old children consume 23.7% more (p<0.001).

Figure 2. Adjusted Mean Changes in Food Intake by Age Group.

Discussion

The key finding of this study is that portion size influences food intake in Chinese children ages 4- to 6-years in a classroom setting. This finding is consistent with lab-based food regulation studies in the United States, which have demonstrated that portion size affects food intake in children ages 2- to 7-years (Fisher, 2007; Fisher, Arreola, et al., 2007; Fisher & Kral, 2008; Fisher, Liu, et al., 2007; Fisher et al., 2003; Rolls et al., 2000).

Age

Chinese children in the 6-year-old age group demonstrated a pattern of eating in the predicted direction. Most notably, they ate 43% more food when served the large portion (p<0.001), even though the portion size was only 30% larger than the reference condition. The magnitude of this effect is consistent with the 25 to 60% increase in intake observed by lab-based controlled-feeding studies (Fisher, 2007; Fisher et al., 2003; Rolls et al., 2000) and suggests that a small change in portion size may elicit disproportionate responses in eating behavior.

Both 4-year-old and 6-year-old children consumed less food when presented with a smaller portion size, although some children asked for additional portions in every portion size condition. While this study was not designed to evaluate the interaction of portion size and number of portions on food intake, future research incorporating the number of portions and partial portions consumed by each child would be helpful to investigate the role of “unit bias” in preschool children. Unit bias is the tendency to eat food in discrete units, rather than eating slightly more or less than what is presented (Geier et al., 2006). In other words, when an individual is given a sandwich, he is likely to consume that entire sandwich, regardless of the size.

However, 4-year old children responded differently to the large portion size compared to 6-year-old children. While the 6-year-old age group ate more food when served a large portion, the 4-year-old age group ate significantly less food when served the large portion. These results are similar to those found by Rolls et al, who reported that 3-year-old children consumed less food when presented with a large portion, although this change was not statistically significant in their analysis (Rolls et al., 2000). One possible explanation is that portion size acts as a visual cue that alters perceptions and expectations about food intake (B. Wansink & Kim, 2005; B. Wansink, Painter, & North, 2005), making it more difficult for children to correctly estimate how much food they have consumed and determine when to stop eating. It is possible that younger children become “overwhelmed” with how much food is presented and thus they stop eating before they would have otherwise. More research is required to understand exactly why younger children eat less when presented large portions.

However, in contrast to this study, Fisher et al reported that children 2- to 9-years old consumed 29% more of an entrée when served a large portion, and that the effect of increased portion size did not vary between younger and older children (Fisher, 2007). The conflicting results regarding age and the effects of portion size suggest that there may not be a single developmental threshold at which portion size begins to influence food intake. Perhaps, instead of achieving a particular developmental milestone where portion size matters, children increasingly respond to portion size cues over time. For example, although a second study by Fisher et al showed no association between age and the effects of portion size in children, they also reported that older children showed greater increases in total energy intake with increased portion size than did younger children (Fisher et al., 2003).

Portion size and Energy Balance

The effect of portion size on food intake did not vary by BMI-for-age z-score, suggesting that excess food consumption as a result of portion size may not be limited to overweight and obese children. This is consistent with previous controlled-feeding studies in children showing that weight status does not influence the effects of portion size on food intake (Fisher, 2007; Fisher, Arreola, et al., 2007; Fisher et al., 2003; Rolls et al., 2000). Importantly, lab-based studies demonstrate that pre-school aged children do not compensate for increased food intake by reducing caloric intake from other foods (Fisher, 2007; Fisher, Liu, et al., 2007; Fisher et al., 2003) or at later meals (Fisher, Arreola, et al., 2007), leading to an overall increase in total daily energy. In fact, in a 7-day free-living study of 4- to 6-year olds, Mrdjenovic et al reported that children were not capable of regulating energy intake at a meal or within 24 hours, and that the most important determinant of food intake was the portion served (Mrdjenovic & Levitsky, 2005).

In the present study, children's hunger was unrelated to how much food they consumed. Fisher and Birch have reported that 5-to 7-year-old girls who are least responsive to hunger cues may be more likely to overeat as a result of portion size and are significantly more likely to become overweight (Fisher & Birch, 2002). Taken together, these results suggest that children who are continuously exposed to increased portion sizes may sustain prolonged increases in excess energy, promoting weight gain, and increasing risk of overweight and obesity. However, the current results did not show that overweight children showed a stronger response to increases in portion size than did normal weight children. Further population-level research is needed to evaluate whether increased portion sizes have contributed to increased rates of childhood obesity in China.

Culture and Consumption Norms

One key question from previous portion size studies is whether the observed effect of portion size and food intake could be due to cultural norms around eating, portion size, or food waste. While we did not explicitly test cultural norms, this study is the first to examine the effects of portion size in China, allowing for a natural comparison to similar studies in the US. In the United States, people tend to consume whole units of food in their entirety (Geier et al., 2006), eating according to the portion presented rather than according to hunger or palatability of food (B. Wansink & Kim, 2005; B. Wansink et al., 2005). American children internalize social norms that encourage them to eat all food given to them, or “clean their plate” (Birch, McPheee, Shoba, Steinberg, & Krehbiel, 1987), impairing responsiveness to physiological cues of hunger and satiety. In this study, 6-year-old Chinese children consumed more food with each additional increase in portion size, regardless of hunger or how much they liked the food, suggesting that a similar mechanism may be at play.

Some scholars have suggested that the One Child policy has created a new set of family norms of lavishing attention on the only child, including overfeeding in which the only child is to be doted upon and overfed (Jing Jung, 2000). In particular, grandparents, who are likely to have experienced food shortages in their lifetime and who frequently live with their children's families, encourage grandchildren to take additional portions and finish all food that is served (Jingxiong et al., 2007). Prevailing attitudes about overfeeding as signs of love and a symbol of health create a unique environment of susceptibility in which Chinese children experience and respond to portion size. However, this study shows that Chinese children and American children demonstrate a similar transition in increasing responsiveness to portion size as they age, suggesting that the effect of portion size on food intake is more reflective of a developmental transition to contextual cues rather than a cultural phenomenon. However, because perceptions and attitudes towards eating and portion size were not tested, more research is needed to understand how consumption norms affect portion size and food intake in this population.

Limitations

While the field-based setting of this study allows for increased applicability to real-life contexts, collecting data in busy kindergarten classrooms made it difficult to monitor every child closely for food spillage or sharing. In addition, investigators were unable to obtain complete recipes from the school cafeteria, limiting the ability to examine energy and nutrient density of foods. This is an important limitation considering Fisher's findings that energy density and portion size have an independent but additive effect on children's food intake (Fisher, Liu, et al., 2007). However, given the similarity in composition of foods and the highly controlled measurement of portions presented in this study, energy density is an unlikely explanation for the observed effects. In addition, features of the DaGuan kindergarten lunchtime setting may have altered the effects of portion size on food intake and may not represent how children consume food in other areas of China. For example, the brevity of the lunch period may have limited the extent to which children consumed additional portions of food. In addition, only the children who attended school on all three study days were included in the analysis. Due to high levels of absenteeism in this kindergarten, the high proportion (30%) of children who did not attend all three days may have introduced selection bias, and there is no way to test whether these children's eating behaviors differ from those who attended all days. In addition, while the liking, hunger, and fullness questionnaires were very similar to those used previously in food preference and consumption assessment in 3- to-5-year old children, (Kranz, Marshall, Wight, Bordi, & Kris-Etherton, 2011) we did not explicitly test for validity or reliability of these instruments in this sample. Finally, this study took place in an urban kindergarten in Yunnan province. Given the substantial regional variation in the socioeconomic context and prevalence of obesity (Wang, 2001), more research is required to understand whether the observed results are generalizable to more rural regions in China.

The key strength of this study is that it replicates lab-based findings in a classroom setting. As children develop, social context becomes increasingly important as the individuals around a child serve as models of eating behaviors, influencing both the preference for and amount of food consumed (Birch, 1980; Pliner & Mann, 2004; Salvy, Coelho, Kieffer, & Epstein, 2007). Children consumed familiar foods in the classroom, their normal lunchtime setting, with their friends and teachers, but variation of external influences such as trading food or skipping lunch was restricted. This study sought to mitigate the effects of socialization by controlling for class effects, suggesting that 6-year-old Chinese children did not eat more simply because the children in their classroom were also eating more. In addition, the field-based nature of this study allowed for increased sample size compared to many lab studies, providing increased power to detect an interaction between age and the effect of portion size on food intake.

Implications

This study adds to the literature by clearly documenting that increased portion size increases food intake in Chinese children. Future research is required to determine why some children are more prone to overeating as a result of increased portion size, and why these effects vary by age, as we were unable to determine why younger children ate less food when given larger portions. In addition, future studies should examine the mechanisms through which portion size affects food intake, and whether this pathway relates to environmental cues, social norms, or normal developmental processes. Portion size could be an important contributor to the increased prevalence of childhood obesity in China if heightened sensitivity to portion size promotes excess food intake and contributes to weight gain. More research is needed to determine if China, like its Western counterparts, has experienced a general increase in average portion size of foods.

If increasing portions are linked to obesity, interventions could be implemented in the school setting, where many children consume a substantial portion of their daily caloric intake. Feasible solutions include alternative methods of presenting and serving foods, including allowing children to serve themselves (Fisher et al., 2003) or reducing the size of serving vessels (Fisher & Kral, 2008). Schools could also regulate energy intake by offering lower energy-density food such as broth-based soup, salad, fruits, and vegetables, which can decrease total energy intake for the meal (Ello-Martin, Ledikwe, & Rolls, 2005; Kral & Rolls, 2004; Rolls, Roe, & Meengs, 2004). Finally, educators and parents can actively teach children to identify and respond to physiological cues of hunger and satiety (Birch et al., 1987).

Conclusion

This study advances knowledge on how portion size affects food intake of Chinese children in a classroom setting. Results indicate that portion size is an important environmental cue that influences food consumption in kindergarten-age Chinese children. Six-year-old children show larger increases in percent change in food intake with increased portion sizes than do 4-year-old children, suggesting that as children develop, they become increasingly susceptible to the effects of portion size. More research is required to understand how portion size operates to affect food intake in this population, who is most susceptible to the effect of portion size, and whether increasing portions are a determinant of the rise in obesity in China.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Not for publication: Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Global Public Health; Mail: CB # 8120 University Square, 123 W. Franklin St, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-3997; Tel: (919) 966-1735; Fax: (919) 966-9159

References

- Addessi E, Galloway AT, Visalberghi E, Birch LL. Specific social influences on the acceptance of novel foods in 2–5-year-old children. Appetite. 2005;45(3):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL. Dimensions of preschool children's food preferences. Journal of nutrition education. 1979;11(2):77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL. Effects of peer models' food choices and eating behaviors on preschoolers' food preferences. Child development. 1980:489–496. [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(Supplement 2):539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, McPheee L, Shoba B, Steinberg L, Krehbiel R. “Clean up your plate”: Effects of child feeding practices on the conditioning of meal size. Learning and Motivation. 1987;18(3):301–317. [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Zimmerman SI, Hind H. The influence of social-affective context on the formation of children's food preferences. Child development. 1980:856–861. [Google Scholar]

- Booth SL, Sallis JF, Ritenbaugh C, Hill JO, Birch LL, Frank LD, Popkin BM. Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity: rationale, influences, and leverage points. Nutrition reviews. 2001;59(3):S21–S36. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb06983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil JE, Palmer CNA, Wrieden W, Murrie I, Bolton-Smith C, Watt P, Hetherington MM. Energy intakes of children after preloads: adjustment, not compensation. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2005;82(2):302–308. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China Education and Research Network. Preschool Education. 2001 Retrieved October 25, 2012, from http://www.edu.cn.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/introduction_1395/20060323/t20060323_3903.shtml.

- Cui Z, Huxley R, Wu Y, Dibley MJ. Temporal trends in overweight and obesity of children and adolescents from nine Provinces in China from 1991–2006. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2010;5(5):365–374. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.490262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey KG, Lönnerdal B. Infant Self-Regulation of Breast Milk Intake. Acta Paediatrica. 2008;75(6):893–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1986.tb10313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding ZY. National epidemiological survey on childhood obesity, 2006. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi Chinese Journal Of Pediatrics. 2008;46(3):179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du S, Lu B, Zhai F, Popkin BM. A new stage of the nutrition transition in China. Public health nutrition. 2002;5(1A):169–174. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ello-Martin JA, Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ. The influence of food portion size and energy density on energy intake: implications for weight management. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2005;82(1):236S–241S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.236S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO. Effects of Age on Children's Intake of Large and Self-selected Food Portions&ast. Obesity. 2007;15(2):403–412. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Arreola A, Birch LL, Rolls BJ. Portion size effects on daily energy intake in low-income Hispanic and African American children and their mothers. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;86(6):1709. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Birch LL. Eating in the absence of hunger and overweight in girls from 5 to 7 y of age. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2002;76(1):226–231. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Kral TVE. Super-size me: portion size effects on young children's eating. Physiology & behavior. 2008;94(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Liu Y, Birch LL, Rolls BJ. Effects of portion size and energy density on young children's intake at a meal. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;86(1):174–179. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Rolls BJ, Birch LL. Children's bite size and intake of an entrée are greater with large portions than with age-appropriate or self-selected portions. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2003;77(5):1164–1170. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MK, Devaney B, Reidy K, Razafindrakoto C, Ziegler P. Relationship between portion size and energy intake among infants and toddlers: evidence of self-regulation. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway AT, Fiorito LM, Francis LA, Birch LL. ‘Finish your soup’: counterproductive effects of pressuring children to eat on intake and affect. Appetite. 2006;46(3):318. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier AB, Rozin P, Doros G. Unit Bias A New Heuristic That Helps Explain the Effect of Portion Size on Food Intake. Psychological Science. 2006;17(6):521–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Sun J, Chen T. Dynamic analysis on the prevalence of obesity and overweight school-age children and adolescents in recent 15 years in China. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi= Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2004;25(2):103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Jung. Feeding China's little emperors: Food, children, and social change. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jingxiong J, Rosenqvist U, Huishan W, Greiner T, Guangli L, Sarkadi A. Influence of grandparents on eating behaviors of young children in Chinese three-generation families. Appetite. 2007;48(3):377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral TV, Rolls BJ. Energy density and portion size: their independent and combined effects on energy intake. Physiology & behavior. 2004;82(1):131. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz S, Marshall YW, Wight A, Bordi PL, Kris-Etherton PM. Liking and consumption of high-fiber snacks in preschool-age children. Food Quality and Preference. 2011;22(5):486–489. [Google Scholar]

- Matthiessen J, Fagt S, Biltoft-Jensen A, Beck AM, Ovesen L. Size makes a difference. Public health nutrition. 2003;6(1):65–72. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrdjenovic G, Levitsky DA. Children eat what they are served: the imprecise regulation of energy intake. Appetite. 2005;44(3):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Patterns and trends in food portion sizes, 1977-1998. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(4):450–453. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piernas C, Popkin BM. Food portion patterns and trends among US children and the relationship to total eating occasion size, 1977–2006. The Journal of nutrition. 2011;141(6):1159–1164. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.138727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P, Mann N. Influence of social norms and palatability on amount consumed and food choice. Appetite. 2004;42(2):227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM. The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world. The Journal of nutrition. 2001;131(3):871S–873S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.871S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto CA, Baik J, Harris JL, Brownell KD. Influence of licensed characters on children's taste and snack preferences. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):88–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Engell D, Birch L. Serving portion sizes influences 5-year-old but not 3-year-old children's food intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2000;100:232–234. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Salad and satiety: energy density and portion size of a first-course salad affect energy intake at lunch. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104(10):1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Larger portion sizes lead to a sustained increase in energy intake over 2 days. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106(4):543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvy SJ, Coelho JS, Kieffer E, Epstein LH. Effects of social contexts on overweight and normal-weight children's food intake. Physiology & behavior. 2007;92(5):840–846. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selya AS, Rose JS, Dierker LC, Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ. A Practical Guide to Calculating Cohen's f2, a Measure of Local Effect Size, from PROC MIXED. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S, Stein AD, Basch CE, Contento IR, Zybert P. Variability and self-regulation of energy intake in young children in their everyday environment. Pediatrics. 1992;90(4):542–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiciklas-Wright H, Mitchell DC, Mickle SJ, Goldman JD, Cook A. Foods commonly eaten in the United States, 1989-1991 and 1994-1996: Are portion sizes changing? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(1):41–47. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenhuis IHM, Leeuwis FH, Vermeer WM. Small, medium, large or supersize: trends in food portion sizes in The Netherlands. Public health nutrition. 2010;13(06):852–857. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009992011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102(3):S40–S51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torun B. Energy requirements of children and adolescents. PUBLIC HEALTH NUTRITION-CAB INTERNATIONAL- 2005;8(7A):968. doi: 10.1079/phn2005791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Cross-national comparison of childhood obesity: the epidemic and the relationship between obesity and socioeconomic status. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30(5):1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Mi J, Shan X, Wang QJ, Ge K. Is China facing an obesity epidemic and the consequences? The trends in obesity and chronic disease in China. International journal of obesity. 2006;31(1):177–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B. Environmental Factors that Increase the Food Intake and Consumption Volume of Unknowing Consumers. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:455–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, Kim J. Bad popcorn in big buckets: portion size can influence intake as much as taste. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2005;37(5):242–245. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, Painter JE, North J. Bottomless Bowls: Why Visual Cues of Portion Size May Influence Intake* &ast. Obesity. 2005;13(1):93–100. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Training Course on Child Growth Asessment, WHO Child Growth Standards Job aid: Measuring and weighting a child. 2011 Retrieved May, 2011, from http://www.who.int/childgrowth/training/jobaid_weighing_measuring.pdf.

- Wu YF, Ma GS, Hu YH, Li YP, Li X, Cui ZH, Kong LZ. The current prevalence status of body overweight and obesity in China: data from the China National Nutrition and Health Survey. Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine] 2005;39(5):316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LR, Nestle M. The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the US obesity epidemic. Journal Information. 2002;92(2) doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.