Abstract

Rationale

Current radiological methods for diagnosing breast cancer detect specific morphological features of solid tumors and/or any associated calcium deposits. These deposits originate from an early molecular microcalcification process which consists of two types: type 1 is calcium oxylate (CO) and type II is carbonated calcium hydroxyapetite (HAP). Type I microcalcifications are mainly associated with benign tumors while type II have been shown to be produced, internally, by malignant cells. No current non-invasive in vivo techniques are available for detecting intratumoral microcalcifications. Such a technique would have a significant impact on breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis in preclinical and clinical settings. 18F-NaF PET has been solely used for bone imaging by targeting the bone HAP. In this work, we provide preliminary evidence that 18F-NaF PET imaging can be used to detect breast cancer by targeting the HAP lattice within the tumor microenvironment with high specificity and soft-tissue contrast-to-background ratio, while delineating tumors from inflammation.

METHODS

Mice were injected with approximately 106 MDA-MB-231 cells subcutaneously and imaged with 18F-NaF PET/CT in a 120 min dynamic sequence when the tumors reached a size of ~250 mm3. Regions-of-interest (ROIs) were drawn around the tumor, muscle, and bone. The concentration of the radiotracer within those ROIs were compared to one another. For comparison to inflammation, rats with inflammatory paws were subjected to 18F-NaF PET imaging.

RESULTS

Tumor uptake of 18F− was significantly higher (p<0.05) than muscle uptake where the tumor-to-muscle ratio was ~3.5. The presence of type II microcalcification in the MDA-MB-231 cell line was confirmed histologically using alizarin red S and von Kossa staining as well as Raman microspectroscopy. No uptake of 18F− was observed in the rat inflamed tissue. Lack of HAP in the inflamed tissue was verified histologically.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides preliminary evidence suggesting that specific targeting of the HAP within the tumor microenvironment with 18F may be able to distinguishing between inflammation and cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, MDA-MB-231, microcalcification, 18F-NaF, 18F−, PET, hydroxyapetite, calcium oxalate

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy among women, accounting for nearly one in three cancers diagnosed in the United States. It is the second leading cause of cancer death among women, causing almost 40,000 deaths in 2011 alone1. Current imaging techniques may fail to detect tumors (false negative) due to their small size or location in the breast, obscurity by nearby organs, or dense breast tissue2.

One significant feature of breast cancer diagnosis is the presence of calcium deposits (average 0.3 mm3 in size) detected via mammograms 3–5. These calcium deposits are potentially the result of condensation of one of two types of microcalcification found within the tumor microenvironment: Type I which contains calcium oxalate dehydrate (CO), and Type II which contains calcium phosphates in the form of hydroxyapatite (HAP) 6. Importantly, Type I deposits are associated with benign breast disease, while malignant cells have the unique capability to produce HAP4, 7, 8. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) on the surface of malignant cells hydrolyses β-glycerophosphate (βG) to glycerol and inorganic phosphate (Pi), which is transported into the cell by the type II family of Na-Pi cotransporters. There, the Pi combines with calcium to produce HAP crystals. HAP then leaves the cells, by unknown mechanisms, into the extracellular matrix. Furthermore, HAP enhances the mitogenesis of mammary cells which amplifes the malignant process resulting in accelerated tumor growth7, 8. Therefore, HAP may be a biomarker for breast malignancy.

Apatite calcification in bone is generally composed of HAP9. The carbonate substitution for phosphate in the bioapatites significantly increases the reactivity of these compounds, especially to anions such as fluoride, allowing them to substitute into the lattice10. Sodium fluoride labeled with 18F− (18F-NaF) has previously been used for bone imaging and bone HAP abundance quantification, as well as for detecting bone metastases using positron emission tomography (PET). The free fluoride dissociates from the sodium and binds to the hydroxyapatite matrix (Ca10(PO4)6OH2) of the skeleton 11, where 18F− substitutes for the OH− of the hydroxyapatite and forms fluoroapatite (Ca10(PO4)6F2)12.

Our working hypothesis is that the same mechanisms of uptake of 18F− in bone apply to breast tumors containing HAP within their microenvironment. Therefore, we investigated the ability of 18F-NaF to detect breast tumors via targeting the HAP microenvironment using mouse models of MDA-MB-231, a triple negative human breast cancer cell line that does not express the genes for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, or Her2/neu. MDA-MB-231 cells produce highly invasive malignant tumors13. Thus, this cell line is a prototype for highly differentiated breast cancer cells with overexpressed epidermal growth factor receptors14. We then assessed the ability of this technique to discriminate between inflammation and cancer by applying it to rat models of acute inflammation.

Methods

All studies were approved by the Vanderbilt University Animal Care and Use Committee prior to conducting the experiments.

Tumor model and imaging

MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator. Four- to five-week old female Foxn1 nu/nu mice were injected subcutaneously in the right hind limb (n = 10) with ~10 million MDA-MB-231 cells in a 1:2 ratio of matrigel and DMEM.

Once the tumor size reached 200–400 mm3, the mice were imaged in a microPET Focus 220 (Siemens Preclinical Solutions, Knoxville, TN) for 120 min in a dynamic acquisition mode with a simultaneous intravenous injection of ~18 Mbq 18F-NaF, provided by the Vanderbilt radiochemistry core. All mice were anesthetized with 2% isofluorane vaporized with oxygen at a steady flow rate of 2.5 L/min during imaging. The dynamic acquisitions consisted of twelve 5 sec frames, four 60 sec frames, one 5 min frame, and eleven 10 min frames. All data sets were reconstructed using the MAP algorithm into 128 × 128 × 95 slices with a voxel size of 0.95 × 0.95 × 0.8 mm3 at a beta value of 0.001. Immediately following the PET scans, the mice were imaged in a microCAT II (Siemens, Knoxville, TN) at X-ray beam intensity of 180 mAs and an X-ray tube voltage of 80 kVp for anatomical coregistration with the PET images. The images were reconstructed at 512 × 512 × 512 with a voxel size of 0.122 × 0.122 × 0.173 mm3.

Inflammation model and imaging

Carrageenan (100 μL 1% in sterile saline) was injected subcutaneously in the rear right footpad of wild type Sprague Dally rats (n = 3). Two hours later, when inflammation was maximal15, the rats were injected with 18F-NaF and imaged in our microPET for 30 min at 1 hr post radiotracer administration in static mode followed by a CT scan as described earlier.

Histological search for hydroxyapetite

A-Staining

Immediately following PET/CT imaging, the tumors and muscle were harvested. For the rat inflammatory model, the feet were harvested at the end of the imaging session. Sections of the harvested tissue (5 μm) were loaded onto glass slides and assessed for mineralization via alizarin red S and von Kossa staining. The staining process was carried out at the Vanderbilt Translational Pathology Shared Resource that uses manufacturer provided staining protocols. Positive staining for alizarin red S (color: red) indicates the presence of calcium while positive staining for von Kossa indicates the presence of calcium phosphates (color: black/brown)8.

B-Raman microspectroscopy

The stained tissue sections, along with stained mouse bone sections provided by the Translational Pathology Core at Vanderbilt University, were subjected to Raman microspectroscopy using an inVia Raman Microscope (Renishaw, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom) using a 785 nm laser and a 50x objective (numerical aperture 0.75). Regions of 100 × 60 μm2 of the sample were mapped over the entire section and Raman spectra were acquired over those areas with an axial resolution of 1 μm. A shift near 960 cm−1 is typical of HAP6, 8, 16. Spectra were processed using Renishaw-WiRE v3.3 software. The bone slides were used for initial calibration. Based on the Raman spectra, regions on the mapped sample were classified using a direct classical least squares method and were color-coded in green indicating a 960 cm−1 shift or black (no shift).

Data analysis

Anatomical regions-of-interest (ROIs) were drawn around the entire tumor, hip bones, lungs, heart, pineal gland, and muscle of the opposing hind limb in the CT images (except for the pineal gland) for each mouse using the medical imaging analysis tool AMIDE17 and superimposed on the PET images. The pineal gland ROI was directly drawn on the PET image as the CT image cannot accurately distinguish brain regions. Time-activity curves (TACs) were established for all ROIs over the entire duration of the dynamic scans. For the rat inflammation studies, ROIs were drawn around each of the paws of the rats in the CT image and superimposed on the PET images.

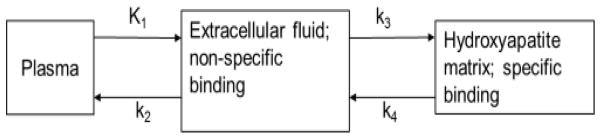

The initial distribution of 18F− is determined by blood flow, after which most of it is cleared rapidly from plasma and excreted by the kidneys12. In the bone, the 18F− ions pass through plasma to the extracellular fluid space, into the shell of bound water onto the hydroxyapatite crystal surface, and into the interior of the crystal, where 18F− exchanges for OH− on the HAP lattice. The kinetics of 18F− moving from the blood plasma to incorporation into fluoroapatite (Ca10(PO4)6F2) have been described by a three compartment model12, 18 as demonstrated in Figure 1. Therefore, we used a similar model to describe tumor uptake of 18F−.

Figure 1.

A three compartment model was used to describe the kinetic distribution of 18F− ions to tumor and bone. K1 is the transfer rate of 18F− from the first compartment 1 (plasma) to compartment 2 (extracellular fluid space) in units of mL/min/g, k2 is the transfer rate from 2 to 1 (1/min), k3 is the transfer rate from 2 to compartment 3 (hydroxyapatite lattice) in units of 1/min, and k4 is the transfer rate. from 3 to 2 (1/min).

The mean concentrations of 18F− within a 20 min time interval between 40 and 60 min post 18F-NaF injection were normalized to the total injected dose (%ID/cc) for the tumor, muscle, and bone regions of the mice. This time window was chosen based on the results we obtained as demonstrated in the results section below. Similarly, the %ID/cc for the rat paws was measured for the entire scan (30 min). A two-tailed Student t-test was used to compare %ID/cc between the tumor and muscle, and between tumor and bone in the mice; the statistical significance threshold was considered to be p<0.05.

Results

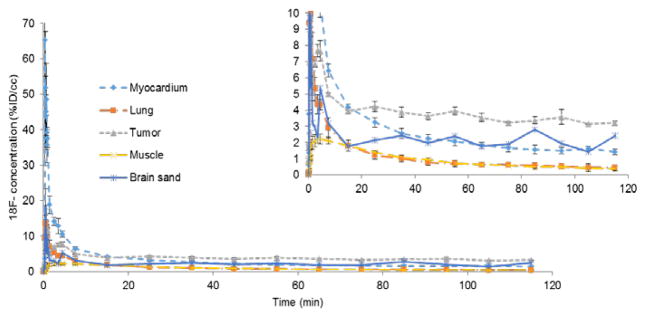

Initial perfusion of 18F− was observed in all tissues, including tumor and muscle, within the first minute following injection of 18F-NaF. The 18F− ions were quickly excreted by the kidneys and by ~ 40 min, residual ions were concentrated in the bone and tumor with little or no signal observed in the muscle as shown in Figure 2. The TACs were fairly flat from 40–120 min indicating a state of equilibrium as demonstrated in Figure 3. Washout of the radiotracer from bone and tumor was fairly slow as indicated by a negligible k4 (please see Table 1). Therefore, we measured the 18F− uptake constant as K18F = K1k3/(k2+k3).

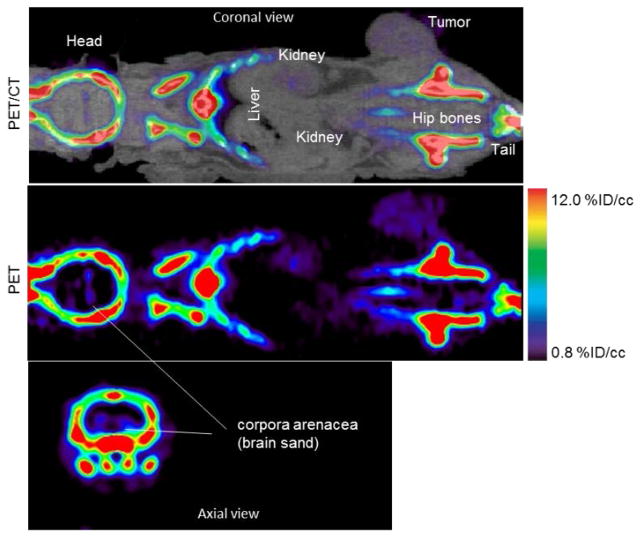

Figure 2.

A 60–80 min summed PET/CT and PET images of 18F− uptake in a mouse bearing MDA-MB-231 tumor and imaged for 120 min. With the windowing level set between 0.8 and 12% ID/cc, bone image is saturated but the tumor and brain sand are visible with high contrast-to-background soft-tissue ratio

Figure 3.

Time-activity curves (TACs) of different regions in the mouse injected with 18F-NaF displayed in the previous figure. The percent injected dose per unit volume (%ID/cc) is the 18F− concentration within each ROI normalized to the total injected dose. The insert is just a zoomed view of the TACs.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of 18F− uptake in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 tumors. The tumors contain hydroxyapetite similar to what is found in normal bone. All value are presented as mean ± SD. K18F is the 18F− uptake constant described as K1k2/(k2+k3).

| Region | K1 (ml/g/min) | k2 (1/min) | k3 (1/min) | k4 (1/min) | K18F (ml/g/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | 0.42 ± 0.19 | 1.27 ± 0.92 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| Bone | 0.25 ± 0.11 | 0.44 ± 0.12 | 0.60 ± 0.42 | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.14 ± 0.08 |

The concentration of 18F− in the tumor between 60 and 80 min was ~3.5 times higher than that of muscle (n = 7, p<0.05) where the %ID/cc within the tumor ROI was 2.9 ± 0.8 (mean ± SD) and that of muscle and bone %ID/cc were 0.8 ± 0.2, and 31 ± 4, respectively.

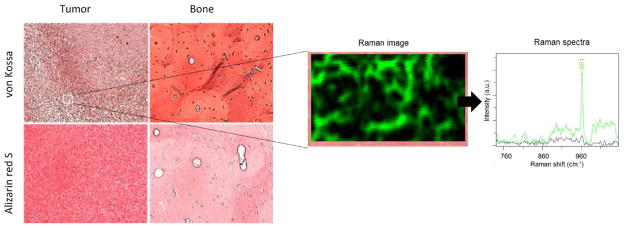

Positive staining for calcium (red; alizarin red S) and calcium phosphate (black/brown; von Kossa) were observed in both the tumor and bone, as shown in Figure 4. The positive stain for von Kossa suggests the presence of Type II calcifications specifically8. A Raman shift of ~960 cm−1 was observed for the MDA-MB-231 slides as shown in Figure 4 where the green color in the 100 × 60 μm2 Raman image taken over the tumor section indicates everywhere a shift near 960 cm−1 was found within that region. Thus, we confirmed the presence of carbonated calcium hydroxyapetite, type II microcalcifications, in the MDA-MB-231 microenvironment. No positive staining using alizarin red S or von Kossa was observed for the muscle, nor did we observe a HAP Raman shift in these tissue.

Figure 4.

Staining of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer samples and normal bone. With von Kossa (red/brown) and alizarin red S (red). The positive von Kossa stains indicate the presence of calcium carbonates suggesting the presence of Type II calcification specifically. A 100 × 60 μm2 region of the same tumor section scanned with a Raman microscope revelas the locations within that region where a 960 cm−1 shift was found (green color in the Raman image and Raman spectra) and where no shift near 960 cm−1 (black color). A shift at ~960 cm−1 indicates the presence of HAP.

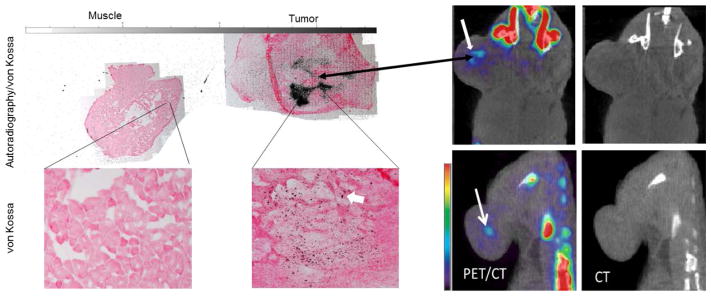

In some cases, we observed a localized region that had a very high concentration of 18F− (approximately nine times higher than muscle, %ID/cc > 8.5, n = 3) as shown in Figure 5. Interestingly, these mice were also the only mice with tumors that had started to ulcerate. In addition, no solid calcium deposits were observed in the CT scans. These mice were excluded from the statistical analysis since their %ID/cc were more than twice the standard deviation from the mean (physiologically, the skin surrounding the tumor was red in appearance indicating the initial stages of ulceration). Autoradiography correlated well with the von Kossa stain results as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

A coronal view of a PET/CT and CT only images of two mice injected with 18F-NaF (right) and the corresponding autoradiography/von Kossa staining of a tumor section and normal muscle (left). A localized region, indicated by the thick white arrow, with high 18F− (about 9 times higher than muscle and 3 times less than bone) was observed in each tumor in the PET images indicating dense HAP. These regions was not observed in the CT images. The autoradiography correlated well with the PET and staining results.

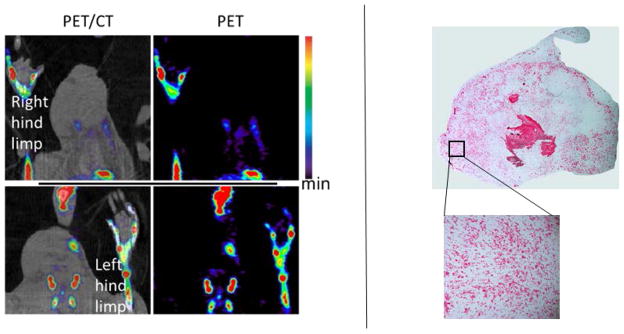

We did not observe any 18F− uptake, nor positive staining for Alizarin red S or von Kossa, in the inflamed soft tissue of the rat paws as shown in Figure 6; for comparison, %ID/cc of non-inflamed soft-tissue and paw bone were 0.9 ± 0.4 and 29 ± 3, respectively. As expected, no Raman shift at ~960 cm−1 was detected in the inflamed tissue, indicating the lack of HAP in them (data not shown as the Raman images appear as just black rectangles).

Figure 6.

(Left) A rat model of acute inflammation (in right footpad) imaged with 18F- NaF PET at maximal inflammation. Uptake of 18F− was limited to bone with no accumulation in the inflammatory soft tissue due to lack of HAP. (Right) A section of the inflamed tissue stained with von Kossa. No positive staining (nor red/brown spots) was observed within in the stained tissue indicating no presence of calcium phosphates or type II microcalcification. The lower and upper limits scale bar are 0.8 and 12 %ID/cc.

Accumulation of 18F− was also observed in the corpora arenacea (brain sand) known to contain hydroxyapetite in humans and animals19–21 as shown in Figure 2.

Discussion

This study presents the first proposed use of 18F-NaF PET imaging to specifically detect tumors based on their HAP abundance. The 18F− concentration was approximately 10 times higher in the bone compared to the tumors, which is expected due to the large density of HAP in the bone and the large bone surface area. This is also indicated by the higher 18F− uptake in the bone illustrated by K18F (please see Table 1). Therefore, in order to visually identify the tumor in the PET images, the windowing level was adjusted to a maximum of 12 % ID/cc as shown in Figure 2, causing the bone signal to appear saturated. For bone structure identification, the high end of the scale bar would be set to at least 45% so that the tumor is not be visible. In addition, the minimum windowing level was set to 0.8 % ID/cc to mask out normal tissue perfusion (e.g., muscle). All analysis of PET images in this work used these same windowing limits.

We are not aware of any negative control tumor models due to the limited studies carried out on HAP and breast cancer. As some breast lesions may be inflammatory lesions, we used an inflammatory rodent model to study the ability of 18F− PET images to distinguish between inflammation and malignancy. No accumulation of 18F− occurred in the rat inflammatory tissue due to lack of HAP (please see Figure 6). Therefore, this technique may indeed represent a novel and potentially reliable noninvasive in vivo method for distinguishing between malignant and inflammatory lesions with high specificity or between lesions that contain HAP and those that don’t. This capability has not been shown in other imaging modalities and techniques. In addition, this technique can be used to measure HAP abundance and the relationship between tumor progression and HAP in preclinical settings.

The lack of accumulation of 18F− in the normal soft tissue, taken with the accumulation of 18F− in the brain sand and the tumor, supports the specificity of 18F− in binding to HAP when present in soft tissue. This occurs through mechanisms similar to those of bone uptake of 18F−, with high soft tissue contrast-to-background ratio as no accumulation of the tracer occurs in soft tissue not containing HAP.

Calcium oxalate is implicated in the composition of most kidney stones22–25. It has been shown that prolonged exposure to high concentrations of NaF (60 mM) was able to dissolve CO in vitro, but this concentration would be considered toxic in vivo 26. Since radiotracer concentrations, including 18F-NaF, are on the order of sub-micromolars or smaller 27, it is highly unlikely that 18F-NaF can break the calcium oxalate bond in benign breast lesions. Therefore, this technique can be used to not only detect single and multicentric tumors with high contrast-to-background ratio, but also to differentiate between type I and type II microcalcifications within the tumor’s microenvironment.

This imaging technique can be rapidly translated to clinical trials since 18F-NaF, or 18F−, is already FDA approved. While the approach is not appropriate for screening, it could be deployed to support mammograms where suspicious lesions or multicentric lesions are detected and biopsy is not feasible. The total-body adsorbed dose is about 0.024 mSv/MBq (0.989 mrem/mCi) or 4.44 mSv for a typical 185 MBq (5 mCi) dose of 18F-NaF injection which is well within the radiation dose tolerance for non-radiation workers28. Additionally, as microcalcifications were detected with 18F-NaF PET imaging when no solid calcium deposits were observed in the CT scan, this technique could be useful in early breast cancer diagnosis before solid calcium deposits are visible in mammograms. This is especially important in cases of chronic inflammation, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), which could progress to malignancy over time 29–31.

It is worth noting that there have been previous studies that used 18F− and sometimes a cocktail of 18F− and 18F-FDG in breast cancer studies 32, 33. Those studies, however, focused on bone metastases of breast cancer, and the patients imaged were at an advanced stage where the cancer had already spread and metastasized at different locations of the skeleton. Our work suggests the use of 18F− imaging within the breast and at a very early stage for means of primary detection, rather than metastases detection.

Conclusion

The results from this study provide the first evidence that PET imaging of breast cancer with 18F− via specifically targeting HAP within the tumor microenvironment may be able to provide a sensitive and non-invasive identification of intra-tumoral microcalcifications with high specificity and contrast-to-background ratio, as this technique targets type II microcalcifications in vivo. Due to radiation and cost, this technique could not be used for initial screening for breast cancer. However, it can be used in identifying multicentric tumors, as well as in discriminating between malignancies and benign factors (e.g. inflammation, cysts, and fat necrosis). Additionally, this technique can be used in the early detection of breast cancer cells progressing from chronic inflammation, DCIS, or LCIS, avoiding repeated biopsies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Zou Yue for animal support. We thank the National Institutes of Health for funding via NCI R01CA138599, NCI P30 CA68485, and NCI P50CA098131. We thank the Kleberg Foundation for their generous support of our Imaging Program.

References

- 1.DeSantis C, Siegel R, Bandi P, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2011. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2011 Nov-Dec;61(6):409–418. doi: 10.3322/caac.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for health care research and quality. Comparative Effectiveness of Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tests for Breast Abnormalities – An Update of a 2006 Report. Effective Health Care Program: Research Review. 2012 Feb [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gershon-Cohen J. The importance of x-ray microcalcifications in breast cancer. The American journal of roentgenology, radium therapy, and nuclear medicine. 1967 Apr;99(4):1010–1011. doi: 10.2214/ajr.99.4.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker R, Rogers KD, Shepard N, Stone N. New relationships between breast microcalcifications and cancer. BrJ Cancer. 2010;103(7):1034–1039. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Going JJ, Anderson TJ, Crocker PR, Levison DA. Weddellite calcification in the breast: eighteen cases with implications for breast cancer screening. Histopathology. 1990 Feb;16(2):119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haka AS, Shafer-Peltier KE, Fitzmaurice M, Crowe J, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Identifying microcalcifications in benign and malignant breast lesions by probing differences in their chemical composition using Raman spectroscopy. Cancer research. 2002 Sep 15;62(18):5375–5380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan MP, Cooke MM, Christopherson PA, Westfall PR, McCarthy GM. Calcium hydroxyapatite promotes mitogenesis and matrix metalloproteinase expression in human breast cancer cell lines. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2001 Nov;32(3):111–117. doi: 10.1002/mc.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox RF, Hernandez-Santana A, Ramdass S, McMahon G, Harmey JH, Morgan MP. Microcalcifications in breast cancer: novel insights into the molecular mechanism and functional consequence of mammary mineralisation. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(3):525–537. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pleshko N, Boskey A, Mendelsohn R. Novel infrared spectroscopic method for the determination of crystallinity of hydroxyapatite minerals. Biophysical journal. 1991 Oct;60(4):786–793. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82113-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson DG. The influence of carbonate on the atomic structure and reactivity of hydroxyapatite. Journal of dental research. 1981 Aug;60(Spec No C):1621–1629. doi: 10.1177/0022034581060003S1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkins RA, Hoh C, Glaspy J, et al. The role of positron emission tomography in oncology and other whole-body applications. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 1992 Oct;22(4):268–284. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(05)80121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czernin J, Satyamurthy N, Schiepers C. Molecular Mechanisms of Bone 18F-NaF Deposition. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010 Dec 1;51(12):1826–1829. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.077933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korah RM, Sysounthone V, Golowa Y, Wieder R. Basic fibroblast growth factor confers a less malignant phenotype in MDA-MB–231 human breast cancer cells. Cancer research. 2000 Feb 1;60(3):733–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aboagye EO, Bhujwalla ZM. Malignant Transformation Alters Membrane Choline Phospholipid Metabolism of Human Mammary Epithelial Cells. Cancer research. 1999 Jan 1;59(1):80–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uddin MJ, Crews BC, Ghebreselasie K, et al. Fluorinated COX–2 inhibitors as agents in PET imaging of inflammation and cancer. Cancer prevention research. 2011 Oct;4(10):1536–1545. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson DG, Featherstone JD. Preparation, analysis, and characterization of carbonated apatites. Calcified tissue international. 1982;34( Suppl 2):S69–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loening AM, Gambhir SS. AMIDE: a free software tool for multimodality medical image analysis. Mol Imaging. 2003;2(3):131–137. doi: 10.1162/15353500200303133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blau M, Ganatra R, Bender MA. 18 F-fluoride for bone imaging. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 1972 Jan;2(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(72)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid HA, Requintina PJ, Oxenkrug GF, Sturner W. Calcium, calcification, and melatonin biosynthesis in the human pineal gland: a postmortem study into age-related factors. Journal of pineal research. 1994 May;16(4):178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1994.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krstic R, Golaz J. Ultrastructural and X-ray microprobe comparison of gerbil and human pineal acervuli. Experientia. 1977 Apr 15;33(4):507–508. doi: 10.1007/BF01922240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alcolado JC, Moore IE, Weller RO. Calcification in the human choroid plexus, meningiomas and pineal gland. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. 1986 May-Jun;12(3):235–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1986.tb00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coe FL, Parks JH, Asplin JR. The pathogenesis and treatment of kidney stones. The New England journal of medicine. 1992 Oct 15;327(16):1141–1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210153271607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemann J., Jr Composition of the diet and calcium kidney stones. The New England journal of medicine. 1993 Mar 25;328(12):880–882. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303253281212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parmar MS. Kidney stones. Bmj. 2004 Jun 12;328(7453):1420–1424. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7453.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006 Jan 28;367(9507):333–344. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low RK, Ho S, Stoller ML. Sodium fluoride dissolution of human calcium oxalate/phosphate stone particles. Journal of endourology / Endourological Society. 1995 Oct;9(5):379–382. doi: 10.1089/end.1995.9.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook GJ. Oncological molecular imaging: nuclear medicine techniques. The British journal of radiology. 2003;76(Spec No 2):S152–158. doi: 10.1259/bjr/16098061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Segall G, Delbeke D, Stabin MG, et al. SNM practice guideline for sodium 18F-fluoride PET/CT bone scans 1.0. J Nucl Med. 2010 Nov;51(11):1813–1820. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.082263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiechmann L, Kuerer HM. The molecular journey from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer. Cancer. 2008 May 15;112(10):2130–2142. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moran M, Haffty BG. Lobular carcinoma in situ as a component of breast cancer: the long-term outcome in patients treated with breast-conservation therapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1998 Jan 15;40(2):353–358. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aulmann S, Penzel R, Schirmacher P, Sinn HP. Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS): risk factor and precursor of invasive lobular breast cancer. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Pathologie. 2007;91:208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iagaru A, Mittra E, Yaghoubi SS, et al. Novel strategy for a cocktail 18F-fluoride and 18F-FDG PET/CT scan for evaluation of malignancy: results of the pilot-phase study. J Nucl Med. 2009 Apr;50(4):501–505. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.058339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doot RK, Muzi M, Peterson LM, et al. Kinetic analysis of 18F-fluoride PET images of breast cancer bone metastases. J Nucl Med. 2010 Apr;51(4):521–527. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]