Leishmaniasis is a protozoal disease caused by flagellates of the genus Leishmania and transmitted by sand fly. The reservoir hosts are humans, dogs, and rodents. It has three different morphological forms: cutaneous, mucocutaneous (MCL), and visceral. The different clinical presentations depend on the interaction between parasite species of leishmania and the genetic and immunological status of the host (1).

Case report

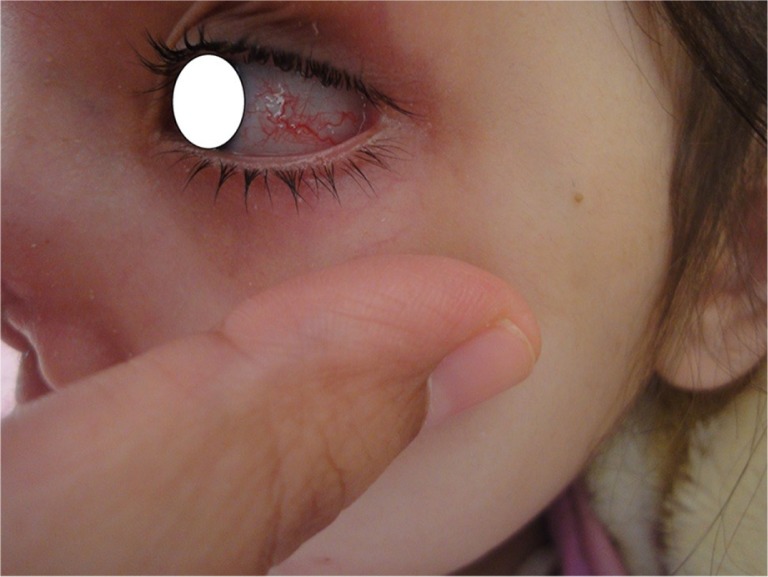

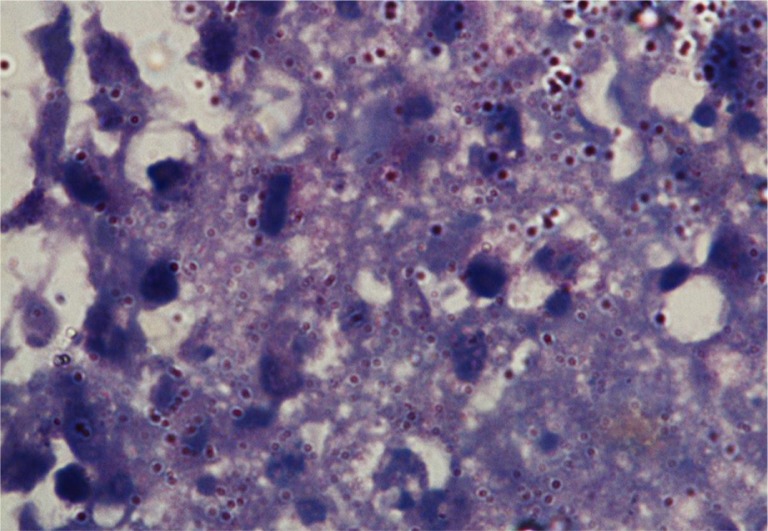

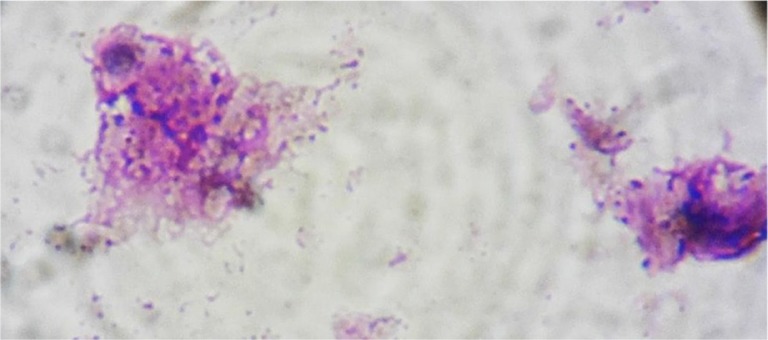

An 11-year-old girl, a known case of ataxia telangectasia, from Ghaser Libya near Wadi Alkof presented with complaints of nasal skin lesion of 5 months duration, followed by purulent rhinitis and destruction of anterior nose with involvement of adjacent area of skin and upper lip. Clinically, telangectasia was evident in conjunctivae (Fig. 1) and skin of face. On walking she had ataxic gait. She had an ulcerated lesion on the anterior part of nose with central purulent crust and raised border. Erythematous papulopustular lesions and superficial small ulcers were seen around the nose, cheeks, upper lip (Fig. 2), and hard palate. Nasal examination revealed congested septum, mucopus in nasal cavity, and nasal ulceration with cartilage destruction. Serology for HIV was negative. Amastigotes inside macrophage were seen by Leishman's stained scraping smears (Fig. 3) and by Giemsa stained histopathological section (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Telangiectasias in the eyes; a marker for diagnosis of ataxia telangiectasia.

Fig. 2.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis.

Fig. 3.

Amastigotes inside macrophage in Leishman's stained smear.

Fig. 4.

Amastigotes were evident by Giemsa stained histopathology (high power).

Treatment with sodium stibogluconate 20 mg/kg/day was administered for 28 days with amphotericin 1 mg/kg. Improvement was only partial, and the patient relapsed once treatment discontinued.

Discussion

Diagnosis of leishmaniasis is based on criteria that consider epidemiological data, clinical features, and laboratory test results: direct smear, culture and inoculation, biopsy, and PCR (2). Based on the clinical picture, the immune state of our patient and the geographical area she came from – Ghaser Libya from where many cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis had been reported – a clinicoepidemiological link was made and MCL was considered as a possible diagnosis, and it was confirmed by demonstrating the leishmania parasites. MCL is considered to be a disease of the New World; it is almost exclusively restricted to South America and is caused typically by Leishmania braziliensis. In rare cases, it may be caused by Old World species like L. aethiopica, L. major, and L. tropica(3, 4).

MCL due to L. infantum had been reported in Mediterranean countries, largely resulting from HIV co-infection (3). Unfortunately, leishmania species identification was not possible in our patient as it was not available.

The nasal mucosa is the most affected area, lesions may be found on the lips, palate, pharynx, and larynx (5), and in advanced disease progressive tissue destruction and marked disfigurement may occur (3, 4). MCL requires prolonged parenteral treatment with pentavalent antimonials or amphotericin B (2, 5). An increase in treatment failure has been documented in several regions of the world (2, 3, 6).

The prognosis of our patient was poor because of late diagnosis, mucosal involvement, as well as the presence of underlying primary immune deficiency disease.

Unfamiliarity with the manifestations of MCL caused a delay in the diagnosis in our patient who has a primary immune deficiency disease, with consequent spreading to adjacent skin and mucosa and with inadequate response to anti-leishmania medications. Well-modulated T-cell response is needed for resolution of cutaneous lesions, whereas inadequate cellular immunity may cause uncontrolled spread of the parasite and often more severe clinical forms (6). In addition, a preserved host immune system is required for a good therapeutic response of leishmaniasis, since it is caused by an intracellular parasite, and the antimonial would act only as an immunomodulator (2).

Conclusion

This case is important from a diagnostic point of view because of its resemblance to other destructing granulomatous lesions of the nose as tuberculosis. To the best of our knowledge, no such case of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis has been documented previously in ataxia telangectasia as a primary immune deficiency disease. Also, the 11-year-old's case is the first case of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis reported from Libya that not only merits documentation but also mandates further research into the epidemiology, geographic distribution, and inter-species interactions of the leishmania parasite.

Safa S. Elfaituri

Dermatology Department

Medical Faculty, Benghazi University

Benghazi, Libya

Dermatology Department

Jumhoria Hospital

Benghazi, Libya

Email: selfaitoury@yahoo.co.uk

Idris Matoug

Pediatric Department

Medical Faculty, Benghazi University

Benghazi, Libya

Immunology and Infectious Departments

Pediatric Hospital

Benghazi, Libya

Hanan Elsalheen

Immunology and Infectious Departments

Pediatric Hospital

Benghazi, Libya

Yousif Belrasali

Immunology and Infectious Departments

Pediatric Hospital

Benghazi, Libya

Fatma Emaetig

Pathology Department

Medical Faculty, Benghazi University

Benghazi, Libya

References

- 1.Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:50. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velozo D, Cabral A, Ribeiro MCM, da Motta JOC, Costa IMC, Sampaio RNR. Fatal mucosal leishmaniasis in a child. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:255–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomson N, Symonds RP, Moir AA, Kendall CH, Wiselka MJ. New World leishmaniasis from Spain. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:757–8. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.926.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bari AU. Clinical spectrum of cutaneous leishmaniasis: An overview from Pakistan. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahluwalia S, Lawn SD, Kanagalingam J, Grant H, Lockwood DN. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: an imported infection among travellers to central and South America. BMJ. 2004;329:842–44. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7470.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Da-Cruz AM, Filgueiras DV, Coutinho Z, Mayrink W, Grimaldi G, Jr, De Luca PM, et al. Atypical mucocutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania braziliensis in an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patient: T-cell responses and remission of lesions associated with antigen immunotherapy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:537–42. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761999000400020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]