Abstract

Background

The study evaluated the effects of a text message intervention on physical activity in adult working women.

Methods

Eighty-seven participants were randomized to an intervention (n=41) or control group (n=46). Pedometer step counts and measures of self-efficacy were collected at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks. Intervention participants received approximately three text messages per week that were motivational, informational, and specific to performing physical activity.

Results

ANCOVA results showed a significant difference between groups for mean steps/day at 12 weeks (6540.0 vs. 5685.0, p=.01) and no significant difference at 24 weeks (6867.7 vs. 6189.0, p= .06). There was no change in mean step counts during or after the intervention compared to baseline. There was a significant difference between groups for mean self-efficacy scores at 12 weeks (68.5, vs. 60.3, p=.02) and at 24 weeks (67.3 vs. 59.0, p=.03).

Conclusions

Intervention participants had higher step counts after 12 and 24 weeks compared to a control group; however, the difference was significant only at the midpoint of the intervention and was attributable to a decrease in steps for the control group. Text messaging did not increase step counts but may be a cost effective tool for maintenance of physical activity behavior.

Keywords: SMS, exercise, self-efficacy, intervention, workplace

Introduction

Participation in regular physical activity has been associated with multiple benefits including reduced risk for obesity, cardiovascular disease, Type II diabetes, depression and osteoporosis.1,2 Despite the positive outcomes of physical activity, the majority of Americans do not participate in the recommended levels of physical activity to achieve health benefits.3 Additionally, an examination of long term trends reveals a declining rate in physical activity in the U.S., particularly among adult women.4 The 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System from the Centers for Disease Control estimates that 48% of females met recommended levels for physical activity and 26% indicated no participation in leisure time physical activity during a typical week.5 As a response to these current patterns, public health entities recommend promotion of physical activity across the lifespan.1,6 In particular, the worksite has been identified as a critical setting for physical activity promotion in adults.7 In 2009, surveillance from the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that 59% of working age women were employed in the civilian labor force with projected increases of nine percent by 2018.8 Given these projections, worksite health promotion programs have the advantage of reaching the majority of adult women.

While the rates of physical activity in adult women are relatively well documented, less is known about the determinants of physical activity in working women. In a qualitative study of working women, participants described social support and the potential to perform activity without a significant change to the daily schedule as facilitators for physical activity.9 Tavares et al. found self-efficacy and intention to be the strongest predictors of physical activity behavior in working women.10 Additionally, both social support and self-efficacy to perform physical activity have emerged as positively associated with physical activity adoption and maintenance in adult and older women, though not specifically working women.11,12 In studies examining perceived barriers to physical activity among working women, the most common reason cited was the time constraints associated with fulfilling multiple roles (e.g. employee, caregiver, spouse, parent) and responsibilities.10,13 Based on previous results, authors have recommended interventions designed to focus on women integrating physical activity into daily life and current routines.14,15

Behavioral Choice Theory (BCT) offers a viable framework for worksite physical activity interventions, and for working women in particular given their cited barriers of time constraints and balancing multiple roles and responsibilities. According to BCT, engaging in physical activity usually involves choosing to be physically active over a competing sedentary behavior where decisions are influenced by access and motivation (i.e., reinforcing value or stimulus). Furthermore, if access is equal to both physical and sedentary activities, people will engage in the more reinforcing activity.16 BCT incorporates both individual-level and environmental influences and has the potential to help understand how environmental factors can influence choices to engage in physical activity.17,18 Though the theory has traditionally been studied in physical activity choices in children, the constructs from BCT, in particular, stimulus or reinforcement to engage in physical activity in the context of equal access, has been recommended for inclusion in physical activity interventions for adults.18–20 In a qualitative study of intentions for physical activity and self-talk strategies, O’Brien et al. found evidence to suggest positive triggering messages may be beneficial to counteract negative self-talk in those who do not have established physical activity patterns and reinforce a choice to be physically active.21

Text messaging via short message service (SMS) to mobile phones offers a cost-effective means to deploy reinforcement or external stimuli to choose physical activity over a competing behavior. Text messaging has been used effectively in smoking cessation, sunscreen use, and weight loss programs.22–25 Interventions which utilized previously emerging technologies, such as the internet and email, to deliver health information were limited by differential access; by contrast, cellular telephone usage is not limited to specific populations. According to results from the Pew Research Center by 2013 91% of the population of the U.S. owned a cellular phone with 81% of adult cell phone users text messaging for communication.26 Therefore, interventions delivered via text have the potential to reach large populations. Furthermore, cell phones are not location dependent, such as a computer or land based phone, and tend to remain in close proximity and easily accessible to owners. Contrary to methods used in other interventions such as email, the Internet, telephone, and handouts, cell phones tend to be utilized by a single person and are likely to remain in close proximity to owners. This provides an opportunity to engage women at specific times and/or places with options for physical activity more readily than through other mediums. Costs for individual text messages range from 10 to 20 cents depending on the service provider, and all providers offer the option of unlimited text message plans. Minimal to no-cost SMS, combined with extensive reach, creates the potential for communities to support physical activity behavior in spite of limited resources.

Reviews of previous text messaging interventions have found evidence for short-term, positive effects related to disease prevention and management and for behavior change interventions.27,28 In a review of SMS delivered behavior change interventions, Fjeldsoe et al. found evidence of positive behavior change in 13 out of 14 reviewed studies.29 They also noted tailored messaging and interactivity (e.g., “SMS dialogue”) to be important features of SMS interventions. In a more recent meta-analysis of SMS interventions for health promotion, Head et al. found no difference in efficacy between interventions that used two-way dialogue versus those using one-way communication.30 While they found evidence for improved outcomes with tailored and targeted messages, theory-based interventions did not have significantly better outcomes compared to those that did not report using a theoretical framework. To date, most text messaging interventions target physical activity as one part of a multi-component strategy to initiate weight loss. These interventions showed an increase in physical activity,31 reduction in weight,24,32 increased psychosocial variables associated with exercise,31 satisfaction with the text messages,32 and recipients would recommend the intervention to a friend.24 Three studies have utilized text messaging with adults to promote physical activity specifically; however, they were all of short duration and were limited by the use of self-report for outcome measures.29,33,34

The present study was designed to capitalize on the assets of cell phone technology and advantages of worksite environments for the purpose of physical activity promotion in working women. Targeted, but not tailored, periodic messaging was deliberately chosen to evaluate the effect of a low cost, low resource (i.e., technical infrastructure and personnel) intervention on physical activity levels. The purpose of the study was to evaluate if reinforcement and stimulus from targeted text messages would increase physical activity in an environment where all participants were provided with similar access to tailored walking maps and an educational website. We hypothesized that the women who received information and support via text messaging were more likely to increase physical activity levels compared to those who did not receive such messages.

Methods

Sample

This study used a randomized control study design. Participants were recruited from female employees at a public university in the Southeastern United States via fliers in workplace mailboxes. Approximately 500 fliers were distributed among an estimated 2300 female full-time employees. Eighty-seven women were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to the intervention group (n=41) or control group (n=46). Eligibility requirements included not being pregnant, answering “no” to all questions on the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire35 or obtaining a physician’s consent to participate, full-time employment (≥ 32 hours/week), a primary work location on campus, and willingness to receive text messages to a personal cell phone. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was approved by the University’s Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

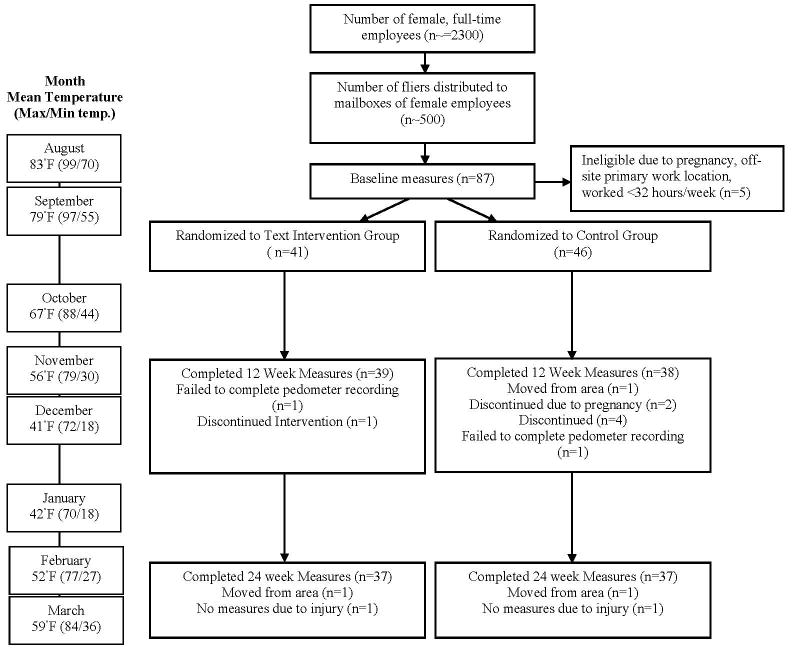

Recruitment occurred on a rolling basis over 5 weeks in late summer and early fall of 2010 (See Figure 1 for time line). Participants completed a baseline questionnaire to detail health history and self-report height and weight for BMI calculation. Participants also completed a self-efficacy questionnaire and physical activity was measured with a pedometer for seven days at baseline, 12 weeks (mid-point of intervention) and 24 weeks (end of intervention). After baseline measurements, participants were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. To control for a potential diffusion effect (i.e. contamination from intervention group to control group), participants from the same department and/or work area were randomly assigned as a group to either the intervention or control groups. Additionally, after the baseline measurements were complete, all participants were provided with three maps displaying walking routes of 1, 2, and 3 miles from each subject’s worksite location to facilitate utilizing the workplace environment for walking. A fourth map provided an alternative 1-mile route or a parking option approximately 1-mile from the subject’s worksite. All participants were also provided a link to the intervention website which included physical activity guidelines,36 PDF versions of all the campus walking maps, and links and suggestions on ways to begin an exercise program and increase physical activity levels. After the mid-term measures were completed at 12 weeks, all participants were provided with a link to a fifth map displaying a walking route from her worksite building to be completed in approximately 30 minutes at a moderate pace.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram with timeline, and mean, maximum, and minimum monthly temperatures.

Measures

Self-efficacy to perform exercise was measured with a 15-item questionnaire developed by Garcia and King.37 A mean self-efficacy score was obtained by calculating the mean of the 15 responses (Range: 0–100). This instrument was shown to have high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha=0.90 and a test-retest correlation of 0.67 (p<.001). In the current study the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.93. Self-efficacy has been shown to be one of the most consistent predictors of physical activity women.11,38,39 Baseline and mid-point responses were used to target the more commonly cited barriers in the intervention component.

Physical activity levels were measured via step counts from an unsealed Omron pedometer (Model # HJ-720ITC). This particular pedometer has been shown to have good validity and reliability in self-paced walking in both healthy and overweight adults with a mean absolute percent error score of < 3.0%.40 Participants were instructed to wear the pedometer for seven days and daily step counts were downloaded directly for analysis at the end of the seven days. Daily step counts were averaged for participants with at least three days of wear time, including two work days and one weekend day, for a minimum of eight hours. Previous research has shown that three days of pedometer measurement is sufficient for estimating mean steps per day in adults.41

Intervention

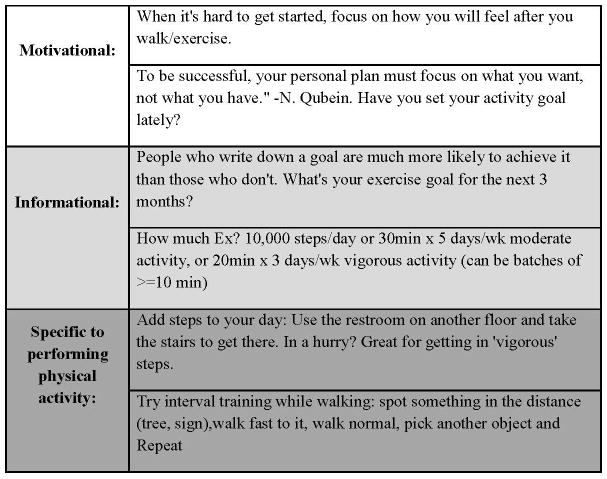

Participants in the intervention group were sent 3 text messages per week to their personal cell phone via SMS for 24 weeks. Fewer messages were sent during holiday weeks when the University was officially closed. Messages were sent by SMS from a free-access email account with the name of the study as the username on the account to the personal cellphone number of intervention participants. To confirm delivery of the text messages by each cellular company, team members (investigators, research assistants) with cellular service provided by the same companies also received the text messages and notified the study leader if messages were not received. Although, the days and times for the messages varied over the course of the intervention, messages were sent during typical wake-time hours and to all participants at the same time. While messages were not sent at a specific time each day, the majority of messages were sent based on optimal time availability for physical activity planning such as early morning for time management of the day, in the hour prior to the lunch break which was standard across campus, and in the hour prior to the official close of University offices. All messages were unique with no repetition of the same message and were limited to 150 characters. All participants received the same content for messages and the same number of messages. Messages were designed to be motivational, informational, and specific to performing physical activity. Content of the messages included the following: 1) Recommended amounts of physical activity needed to meet guidelines; 2) Specific suggestions for ways to meet the guidelines; 3) Self-regulation strategies such as goal-setting, relapse prevention, engaging social support, self-monitoring, time management and reinforcement; and 4) Strategies to address the most common barriers identified from the baseline and mid-point self-efficacy instrument. Content was adjusted for weather conditions (e.g., alternatives to prescribed walks for rainy days and higher temperatures) and seasonal events (e.g., change from Daylight Savings Time, strategies to engage in physical activity over holiday breaks). Examples of the types of messages are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Examples of Text Messages by Type

Survey Assessment

At 12 and 24 weeks, intervention participants completed a survey that examined participant satisfaction with the text messages. Questions were asked about satisfaction with the content of the messages, timing, and number of messages received each week with response options ranging from 1–5 (Very dissatisfied to Very satisfied). Participants also rated statements relating to their perception of the influence of the text messages on physical activity levels such as “The text messages increased my daily walking,” and “I look for ways to increase my walking during my work day” with response options of True, Somewhat True, Somewhat Not True, and Not True. An additional item assessed the following statement “The text messages motivate me to be:” with response options of very inactive, inactive, continued with same activity, active, and very active.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM, Version #19) and Stata (College Station, TX Version 12.1). Bivariate analysis using t-tests assessed baseline differences between the intervention and the control group for age, BMI, health history, self-efficacy, and pedometer step counts. Steps counts were assessed for normal distribution. Two ANCOVAs, with the baseline scores as the covariate, examined differences in step counts and self-efficacy to perform exercise between the groups at 12 and 24 weeks. Intention to treat analysis was used and the Alpha level was set a priori at .05. The ANCOVA analysis was repeated to account for potential effects due to clustering. Post-hoc t-tests were also used to assess within-group changes for step counts and self-efficacy scores, including changes in the top five most commonly cited barriers to physical activity. We tested for the mediating effect of self-efficacy on the impact of the intervention on physical activity levels, with the following sequential tests: 1) A significant outcome for self-efficacy regressed on group assignment (intervention and control); 2) A significant outcome for step counts regressed on group assignment; 3) A significant outcome for step counts regressed on self-efficacy and 4) the effect of group assignment on step counts had to be less than in the third regression equation as compared to the second regression equation.42

Results

Eighty-seven women completed baseline measures to participate in the study. At 12 weeks, 77 participants (n=39 for the intervention group, n=38 for the control group) provided at least 3 days of pedometer data. At 24 weeks, 74 participants (n=37 for the intervention group, n=37 for the control group) completed the follow-up measures (Figure 1). The attrition rate was 10% for the intervention group and 22% for the control group at 24 weeks. There was no difference in age, BMI, baseline step counts, or self-efficacy scores between participants who dropped out and those who completed the study. A total of 64 text messages were sent over the course of the study to intervention participants.

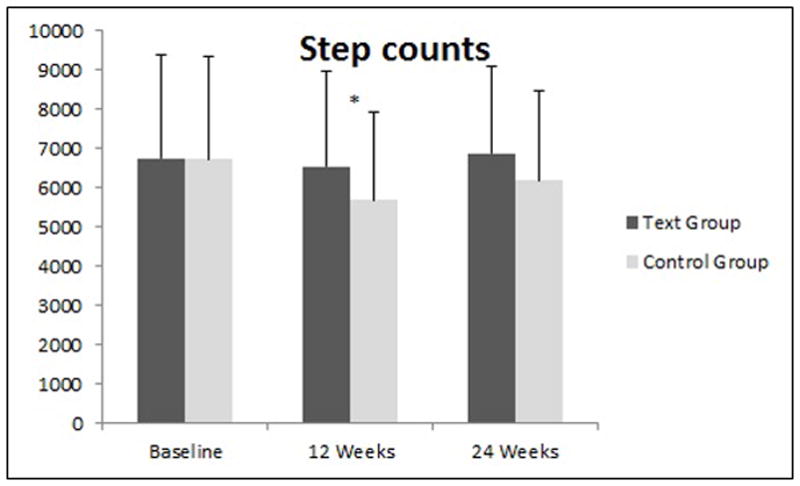

There was evidence of skewed baseline data with post-intervention data meeting normality criteria. Per the methods as described by Vickers the distributions and group sizes indicated ANCOVA to be the preferred method for comparison.43 Mean baseline and follow-up measures are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and control participants at baseline for age, BMI, activity levels, or self-efficacy. ANCOVA results showed a significant difference between the intervention and control group for mean steps/day at 12 weeks (6540.0±2426.6 vs. 5685.0±2233.6, p=.01). Figure 3 shows the change in mean step/day over time from the baseline to the end of the intervention. There was no significant difference in mean steps/day at 24 weeks (6867.7 SD±2227.0 vs. 6189.0 SD±2297.0, p= .06).

Table 1.

Baseline and follow-up measures

| Intervention Mean (SD) N=41 |

Control Mean (SD) N=46 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | 48.9 (10.6) | 45.4 (10.7) |

| BMI | 28.9 (6.0) | 29.5 (7.0) |

| Step Counts | ||

| Baseline | 6752.1 (2653.3) | 6737.9 (2619.3) |

| 12 weeks | 6540.0 (2426.6) | 5685.0 (2233.6)** |

| 24 weeks | 6867.7 (2227.0) | 6189.0 (2297.0)* |

| Self-efficacy | ||

| Baseline | 65.1 (17.7) | 64.7 (17.3) |

| 12 weeks | 68.4 (16.4) | 60.3 (17.7)* |

| 24 weeks | 67.3 (18.6) | 59.0 (19.5)* |

p<0.05 compared to baseline measure

p<0.001 compared to baseline measure based on paired t-tests.

Figure 3.

Mean steps day with standard deviations at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks.

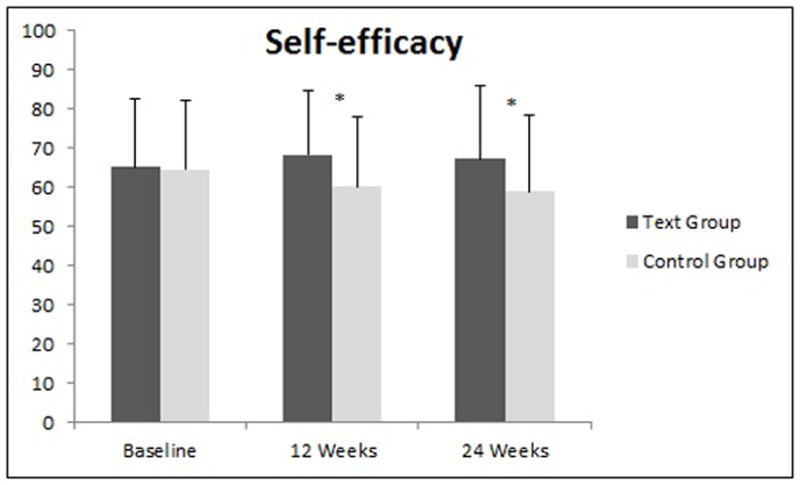

ANCOVA results showed a significant difference between the intervention and control participants for mean self-efficacy score at 12 weeks (68.4±16.4 vs. 60.3±17.7, p=.02) and at 24 weeks (67.3±18.6 vs. 59.0±19.5, p=.03). Figure 4 displays the mean self-efficacy scores over time. Post hoc analysis showed that among the five most commonly cited barriers to physical activity from the self-efficacy questionnaire (exercise not enjoyable, work constraints, bad weather, hectic schedule, vacation), there were no significant mean changes in the intervention group and among the control group only the barrier of ‘bad weather’ decreased significantly compared to baseline (Baseline mean ± SD 55.9 ± 32.1 vs. 45.9 ± 31.8 at 12 weeks, p=0.05; baseline 55.9 ± 32.1 vs.41.3 ± 31.1 at 24 weeks, p=0.01) indicating lower perceived self-efficacy of exercising in bad weather. At 12 and 24 weeks there was no significant mediating effect of self-efficacy on step counts. The ANCOVA for change in step counts and self-efficacy was repeated with standard errors adjusted for clusters with no significant change in the outcomes.

Figure 4.

Mean self-efficacy scores with standard deviations at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks.

At 12 weeks 73% of the intervention group reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the text messages and no participants reported dissatisfaction with the text messages. After 24 weeks, one subject reported dissatisfaction with the text messages and 81% were satisfied or very satisfied with the text messages received. Reasons for satisfaction included liking the encouragement and motivation to exercise and reasons for dissatisfaction were not liking the content or frequency of the messages or still not having time to exercise despite the reminder. The majority of the text recipients indicated that the messages motivated them to be active or very active (59% at 12 weeks, 56% at 24 weeks). In response to the statement, “The text messages increase my daily walking” 51% agreed at 12 weeks and 64% agreed at 24 weeks.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of a text message intervention on physical activity levels in a group of working women. The intervention did not increase physical activity levels, as hypothesized. However, step counts did not decrease significantly at the midpoint of the study for intervention participants as they did for controls. There was a significant difference in self-efficacy to perform physical activity between intervention and control participants at the mid-point and end of the intervention although self-efficacy did not appear to mediate physical activity levels. This study was initiated in the early fall with the follow-up in the winter and spring. Multiple studies have found evidence for a “seasonal effect” on activity levels in adult women with average walking distance decreasing in winter months compared to spring and summer.44–46 The present study is notable for preventing a significant decrease in activity levels during the winter months as compared to the control group, with corresponding maintenance of self-efficacy to “exercise in bad weather” in the intervention group compared to a significant decrease in this measure in the control group. Additionally, overall self-efficacy levels in the control group decreased significantly along with activity levels, but were maintained in the intervention group. These results suggest that targeted text messaging, may be better utilized to support maintenance of physical activity behavior. In the context of BCT, it appears the stimulus of the messages was sufficient to maintain but not increase physical activity levels during the winter months. Extending the intervention for 24 weeks was not sufficient to increase physical activity levels.

We intentionally chose targeted messaging over tailored messaging to minimize cost and technical infrastructure needs. While the findings do not support the use of such an intervention over a long-term period, the short-term results suggest a potential role for this type of text messaging as an adjunct to community-based physical activity promotion programs. A targeted text messaging component could be integrated into worksite interventions, community programs, and state-wide initiatives (e.g., Active U, Scale Back Alabama, Wheeling Walks, Be Active Appalachia, and Movement for Motion North Carolina) with minimal additional resources. Given the relatively high attrition from community based physical activity programs, an add-on component of targeted text messaging is worth exploring in such programs.

According to a review by Trost et al.12 examining the correlates of physical activity in adults, self-efficacy was found to be the most consistent correlate of participation in physical activity. In the current study, self-efficacy levels were equivalent at baseline for the intervention and control groups. However, mean self-efficacy scores decreased significantly in the control group after the baseline assessment. The maintenance of self-efficacy levels in the intervention group lends evidence to support the idea that sustained physical activity is linked to self-efficacy. It is beyond the measures taken during this study to clarify the mechanism by which both self-efficacy and physical activity were maintained in the intervention group. It is possible the texts provided triggers which then influenced self-efficacy to influence physical activity participation. Alternatively the texts may have provided reinforcement to be physically active which allowed the participants to experience past performance accomplishments, thereby increasing self-efficacy.

A meta-analysis examined the best method to affect self-efficacy in physical activity interventions and concluded that a) interventions had a small effect on self-efficacy and b) interventions that included feedback on past or others performance produced the highest levels of self-efficacy; whereas persuasion (either delivered verbally or through other means such as e-mail), graded mastery (shaping based on goal setting) and barrier identification were associated with lower levels of self-efficacy.47 The texts in this study provided specific instructions to be active in the workplace environment and overcome barriers to physical activity participation that may have occurred in the environment at the time of the intervention (i.e. weather, construction etc), meaning the texts utilized persuasion to initiate physical activity, which is counterintuitive to the meta-analysis results. It appears that identifying methods to overcome specific barriers versus having participants just think about physical activity barriers might be a more productive intervention strategy to promote physical activity.47

We acknowledge several limitations to this study. First, this study did not evaluate responses to the content of individual messages; therefore, it is not known how variations in the content of the messages influenced activity levels. It is possible that some messages were more influential or motivational than others. Additionally, the optimal number of messages per week to elicit the greatest response cannot be determined from the results of this study. Second, this study was conducted on a college campus, and while the majority of participants were staff with assigned work hours, some may have had more flexible work hours than others, allowing them to participate more often in physical activity at work. The setting also limits the generalizability to other worksites. Additional research is needed to determine if this type of intervention would be effective in a more restrictive work environment or at a worksite without any “campus” where physical activity can be performed. Since pedometers were the sole means to assess physical activity it is possible participants engaged in physical activity that was not accurately measured by step counts such as swimming or bicycling. Evidence to support reactivity to unsealed pedometers is mixed.48–51 The evidence to support significant reactivity was strongest in studies where participants were asked to record daily step counts in a log, which the participants in the current study were not required to do. While it is possible the availability of steps/day from the pedometer led to changes in behavior, the randomized study design should control for differences between groups. Of note, this study was not restricted to sedentary participants only. Consistent with typical community-based and worksite sponsored interventions participants were enrolled regardless of baseline physical activity levels. Although the majority of participants did not meet the recommendations of achieving 10,000 steps, the wide range of step counts across participants may have limited the potential to see significant increases in mean step counts.

This is the first known randomized control study to utilize text messaging to promote physical activity for women who work full-time with an objective measure of physical activity. This study showed that text messaging is a viable mode to support physical activity and self-efficacy in working women. It has the potential to be widely accessible, inclusive of typically marginalized populations, and utilized with minimal cost. Further research is needed to determine optimal content and timing of messages, and to determine how to increase effects on physical activity for the long term.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute on Aging (T32AG027677).

Footnotes

© 2014 Human Kinetics, Inc. as accepted for publication

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Nancy M. Gell, Email: gell.n@ghc.org, Group Health Research Institute, 1730 Minor Ave Suite 1600, Seattle, WA 98101.

Danielle D. Wadsworth, Email: dwadsworth@auburn.edu, School of Kinesiology, Auburn University, Auburn, AL.

References

- 1.Fletcher GF, Balady G, Blair SN, et al. Statement on Exercise: Benefits and Recommendations for Physical Activity Programs for All Americans A Statement for Health Professionals by the Committee on Exercise and Cardiac Rehabilitation of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996;94(4):857–862. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian medical association journal. 2006;174(6):801–809. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control FastStats on Physical Activity. [Accessed February 12, 2013]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/exercise.htm.

- 4.Brownson RC, Boehmer TK, Luke DA. Declining rates of physical activity in the United States: what are the contributors? Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:421–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. [Accessed January 17, 2013]; http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/BRFSS/sex.asp?cat=PA&yr=2007&qkey=4418&state=UB.

- 6.Health People 2020. [Accessed December 11, 2012]; http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=33.

- 7.Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: A systematic review. The names and affiliations of the Task Force members are listed in the front of this supplement and at www.thecommunityguide.org. Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Peter A. Briss, MD, Community Guide Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, MS-K73, Atlanta, GA 30341. E-mail: PBriss@cdc.gov. American journal of preventive medicine. 2002;22(4):73–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed May 10, 2012]; http://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2011/women/pdf/women_bls_spotlight.pdf.

- 9.Tessaro I, Campbell M, Benedict S, et al. Developing a worksite health promotion intervention: Health works for women. American Journal of Health Behavior. 1998;22(6):434–442. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavares LS, Plotnikoff RC, Loucaides C. Social-cognitive theories for predicting physical activity behaviours of employed women with and without young children. Psychology, health & medicine. 2009;14(2):129–142. doi: 10.1080/13548500802270356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sternfeld B, Ainsworth BE, Quesenberry C., Jr Physical activity patterns in a diverse population of women. Preventive medicine. 1999;28(3):313–323. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: review and update. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2002 doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcus BH, Pinto BM, Simkin LR, Audrain JE, Taylor ER. Application of theoretical models to exercise behavior among employed women. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1994;9(1):49–55. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scharff DP, Homan S, Kreuter M, Brennan L. Factors associated with physical activity in women across the life span: implications for program development. Women & health. 1999;29(2):115–134. doi: 10.1300/J013v29n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speck BJ, Harrell JS. Maintaining regular physical activity in women: evidence to date. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2003;18(4):282–293. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein LH, Roemmich JN. Reducing sedentary behavior: role in modifying physical activity. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2001;29(3):103–108. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein LH. Integrating theoretical approaches to promote physical activity. American journal of preventive medicine. 1998;15(4):257–265. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salmon J, Owen N, Crawford D, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Physical activity and sedentary behavior: a population-based study of barriers, enjoyment, and preference. Health psychology. 2003;22(2):178. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen N, Sugiyama T, Eakin EE, Gardiner PA, Tremblay MS, Sallis JF. Adults’ sedentary behavior: determinants and interventions. American journal of preventive medicine. 2011;41(2):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM. Time displacement and confidence to participate in physical activity. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2011;18(3):229–234. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Brien Cousins S, Gillis MM. “Just do it before you talk yourself out of it”: the self-talk of adults thinking about physical activity. Psychology of sport and exercise. 2005;6(3):313–334. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong AW, Watson AJ, Makredes M, Frangos JE, Kimball AB, Kvedar JC. Text-message reminders to improve sunscreen use: a randomized, controlled trial using electronic monitoring. Archives of dermatology. 2009;145(11):1230. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obermayer JL, Riley WT, Asif O, Jean-Mary J. College smoking-cessation using cell phone text messaging. Journal of American College Health. 2004;53(2):71–78. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.2.71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, et al. A text message–based intervention for weight loss: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research. 2009;11(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodgers A, Corbett T, Bramley D, et al. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tobacco control. 2005;14(4):255–261. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pew Internet and American Life Project. [Accessed January 16, 2014]; http://pewinternet.org/Commentary/2012/February/Pew-Internet-Mobile.aspx.

- 27.Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiologic reviews. 2010;32(1):56–69. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishna S, Boren SA, Balas EA. Healthcare via cell phones: a systematic review. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2009;15(3):231–240. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fjeldsoe BS, Miller YD, Marshall AL. MobileMums: a randomized controlled trial of an SMS-based physical activity intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;39(2):101–111. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9170-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;97:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurling R, Catt M, Boni MD, et al. Using internet and mobile phone technology to deliver an automated physical activity program: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(2):e7. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joo N-S, Kim B-T. Mobile phone short message service messaging for behaviour modification in a community-based weight control programme in Korea. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2007;13(8):416–420. doi: 10.1258/135763307783064331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prestwich A, Perugini M, Hurling R. Can the effects of implementation intentions on exercise be enhanced using text messages? Psychology and Health. 2009;24(6):677–687. doi: 10.1080/08870440802040715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prestwich A, Perugini M, Hurling R. Can implementation intentions and text messages promote brisk walking? A randomized trial. Health psychology. 2010;29(1):40. doi: 10.1037/a0016993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q) Canadian journal of sport sciences. 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Committee PAGA. Physical activity guidelines advisory committee report, 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia AW, King AC. Predicting long-term adherence to aerobic exercise: A comparison of two models. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharpe PA, Granner ML, Hutto BE, Wilcox S, Peck L, Addy CL. Correlates of physical activity among African American and white women. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2008;32(6):701–713. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilbur J, Michaels Miller A, Chandler P, McDevitt J. Determinants of physical activity and adherence to a 24-week home-based walking program in African American and Caucasian women. Research in nursing & health. 2003;26(3):213–224. doi: 10.1002/nur.10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holbrook E, Barreira T, Kang M. Validity and reliability of Omron pedometers for prescribed and self-paced walking. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2009;41(3):670. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181886095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tudor-Locke C, Burkett L, Reis J, Ainsworth B, Macera C, Wilson D. How many days of pedometer monitoring predict weekly physical activity in adults? Preventive medicine. 2005;40(3):293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1986;51(6):1173. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vickers AJ. Parametric versus non-parametric statistics in the analysis of randomized trials with non-normally distributed data. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2005;5(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buchowski MS, Choi L, Majchrzak KM, Acra S, Matthews CE, Chen KY. Seasonal changes in amount and patterns of physical activity in women. Journal of physical activity & health. 2009;6(2):252. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee C, Lawler G, Panemangalore M, Street D. Nutritional status of middle-aged and elderly females in Kentucky in two seasons: Part 1. Body weight and related factors. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 1987;6(3):209–215. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1987.10720183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tudor-Locke C, Bassett DR, Jr, Swartz AM, et al. A preliminary study of one year of pedometer self-monitoring. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28(3):158–162. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2803_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ashford S, Edmunds J, French DP. What is the best way to change self-efficacy to promote lifestyle and recreational physical activity? A systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15(2):265–288. doi: 10.1348/135910709X461752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Motl RW, McAuley E, Dlugonski D. Reactivity in baseline accelerometer data from a physical activity behavioral intervention. Health psychology. 2012;31(2):172. doi: 10.1037/a0025965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clemes S, Parker R. Increasing our understanding of reactivity to pedometers in adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2009;41(3):674. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cae32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marshall AL. Should all steps count when using a pedometer as a measure of physical activity in older adults? Journal of Physical Activity and Health (JPAH) 2007;4(3):305–314. doi: 10.1123/jpah.4.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matevey C, Rogers LQ, Dawson E, Tudor-Locke C. Lack of reactivity during pedometer self-monitoring in adults. Measurement in physical education and exercise science. 2006;10(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]