Abstract

Child maltreatment has been linked with a number of risk behaviors that are associated with long-lasting maladaptive outcomes across multiple domains of functioning. This study examines whether the ages of onset of four risk behaviors—sexual intercourse, alcohol use, drug use, and criminal behavior—mediate the relationship between child maltreatment and outcomes in middle adulthood among a sample of court-documented victims of child abuse/neglect and matched controls (N = 1,196; 51.7% female; 66.2% White, 32.6% Black). Adult outcomes included employment status, welfare receipt, internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depressive symptoms, substance use problems, and criminal arrests. The results indicated gender differences in these relationships. For females, age of onset of sexual intercourse mediated the relationship between child abuse/neglect and both internalizing symptoms and substance use problems in middle adulthood. For males, age at first criminal arrest mediated the relationship between child abuse/neglect and extensive involvement in the justice system in middle adulthood. Age of onset of alcohol use and drug use did not mediate the relationship between child abuse/neglect and middle adult outcomes. This study expands current knowledge by identifying associations between early initiation of risk behavior in one domain and later, continuing problems in different domains. Thus, early initiation of specific risk behaviors may have more wide-ranging negative consequences than are typically considered during intervention or treatment and strategies may need to target multiple domains of functioning.

Keywords: child abuse and neglect, early onset, risk behaviors, age of onset

Introduction

In discussing early substance use, Robins and Przybeck (1985) suggested that “predictors of age of initiation may be what forecasts outcome rather than early use itself” (pp. 178). More recently, in discussing early offending, Piquero, Farrington, and Blumstein (2007) noted that “only a few studies have examined how age of onset relates to offending frequency among active offenders with age, and no research has linked these two criminal career dimensions (onset age and individual offense frequency) together in adulthood. Thus, it is not clear what an early age of onset predicts” (pp. 61). Child abuse and neglect have been linked to both of these social problems, in addition to other wide-ranging negative outcomes across the lifespan (Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb & Janson, 2009). However, it is not known whether the age of onset of these risk behaviors acts as a pathway for subsequent negative consequences for victims of childhood abuse and neglect. Previous research has consistently found associations between early-onset risk behaviors and later manifestation of these same risk behaviors [e.g., early-onset alcohol use is associated with substance use disorders in adulthood (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009)], but few studies have examined whether these early-onset risk behaviors predict risk behaviors in other domains of functioning. Because there is frequent co-occurrence of problem behaviors across different domains, such as substance abuse and internalizing problems (O’Neil, Connor, & Kendall, 2011) or juvenile arrest and low educational attainment (Kirk & Sampson, 2013), it is likely that early-onset risk behavior in one domain impacts functioning in other domains. While extensive research has documented consequences of child abuse and neglect, to our knowledge, research has not examined the role of early onset risk behaviors in relation to consequences of child abuse and neglect, although understanding the mechanisms by which children exposed to these adverse experiences subsequently engage in problematic behaviors is clearly important. Thus, the purpose of the present study is to examine whether the age of onset of four risk behaviors that have received considerable attention in the literature and whose relationships with child abuse and neglect have been documented in prospective longitudinal studies – sexual intercourse, alcohol use, drug use, and criminal behavior – mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and outcomes in middle adulthood.

Impact of Child Abuse and Neglect on Risk Behaviors

Child maltreatment has been associated with outcomes across many domains of functioning (Gilbert et al., 2009), including depression and anxiety (Johnson, Smailes, Cohen, Brown, & Bernstein, 2000), posttraumatic stress disorder (Widom, 1999), risky sexual behavior (e.g., prostitution; Widom & Kuhns, 1996), criminal behaviour (Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Smith & Thornberry, 1995), substance abuse and dependence (Widom, Marmorstein, White, 2006), low intelligence (Perez & Widom, 1994), and poor academic achievement (Eckenrode, Laird, & Doris, 1993). In addition, previous research has identified associations between child maltreatment and earlier onset of risk behaviors. For example, maltreatment of all types has been linked to early-onset problem behaviors (e.g., cigarette use, sexual intercourse, illicit drug use, arrest, alcohol use; Eckenrode et al., 2001). Exposure to physical abuse, specifically, has been linked to early-onset externalizing problems in elementary school (Egeland, Yates, Appleyard, & van Dulmen, 2002) and youth homelessness (Gaets, 2004), as well as early onset of substance use among females (Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 2010) and early onset of sexual activity among females (Small & Luster, 1994). Exposure to sexual abuse, specifically, has been linked to earlier use of alcohol and illicit drugs (Hawke, Jainchill, & Leon, 2000) and earlier sexual activity (Brown, Cohen, Chen, Smailes, & Johnson, 2004).

Early Engagement in Risk Behaviors

Previous research has also documented associations between early engagement in risk behaviors and subsequent maladaptive outcomes across multiple domains of functioning. Although much of the research examining early-onset risk behaviors has focused on associations with later problems within that same domain (e.g., early-onset conduct problems leads to life-course-persistent antisocial behavior; Moffitt, 1993), some research has identified cross-domain outcomes associated with early-onset sexual intercourse, alcohol and drug use, and criminal behavior.

Early engagement in sexual intercourse

Although sexual intercourse is a normative behavior and often considered an appropriate developmental milestone, early initiation can be problematic for a number of reasons. Those who become sexually active by early adolescence are less likely to use effective contraception, engage in sexual behavior more often, and have more sexual partners (French & Dishion, 2003), all of which increase the risk of pregnancy and transmission of sexually transmitted disease. Early initiation of sexual intercourse has also been associated with outcomes associated with delinquency and substance use, such as weapon-carrying (French & Dishion, 2003), cigarette use (Coker, Richter, Valois, & McKeown, 1994), and getting into physical fights (Robinson, Telljohann, & Price, 1999).

Early alcohol and drug use

Early initiation of substance use has been associated with use of other, more dangerous drugs (Grant & Dawson, 1998), risky sexual behavior (e.g., having sex with more than 6 partners), and poor academic achievement (Hyman, Garcia, & Sinha, 2006), as well as increased risk of exposure to traumatic events (Kingston & Raghavan, 2009). Alcohol use before age 15 is associated with a fourfold increase in the likelihood of meeting criteria for alcohol dependence (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009). Marijuana, in particular, is considered to be a “gateway drug”—one that leads to the use of more dangerous drugs (e.g., cocaine), indicating that early use places youth at particular risk.

Early engagement in criminal behavior

Research on the long-term effects of early antisocial behavior, delinquency, and arrest consistently indicates that individuals who begin offending at a younger age are more likely to persist in their criminal activity and more likely to commit more serious offenses and antisocial behaviors than those who begin offending at an older age (Sampson & Laub, 2005). In studies that examined cross-domain relationships, early antisocial behavior has been associated with increased risk for being a high school dropout (Sweeten, 2006), having lower occupational success (low earnings and unemployment; Allgood, Mustard, & Warren, 1999), divorce or separation (Farrington, 1989), substance abuse (Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2005), and early mortality (Pajer, 1998).

Gender Differences

There are also differences between men and women in prevalence rates and age of onset of these risk behaviors. Compared to females, males typically engage in sexual activity at a younger age (Upchurch, Levy-Storms, Sucoff, & Aneshensel, 1998), drink more heavily in adolescence (Cardenal & Adell, 2000) and adulthood (Pitkänen, Lyyra, Pulkkinen, 2005), are more likely to suffer from substance use disorders (Brady & Randall, 1999), and engage in offending behavior earlier and more frequently (Mazerolle, Brame, Paternoster, Piquero, & Dean, 2000). Gender differences have also been noted in the relationship between child abuse and neglect and a number of behavioral, emotional, and socioeconomic outcomes, including adult illicit drug use (Widom, Marmorstein, & White, 2006), coping and posttraumatic stress responses to maltreatment (Ullman & Filipas, 2005), delinquency (Herrera & McCloskey, 2001), and education, employment, earnings, and assets (Currie & Widom, 2010). Given these findings from previous research, a secondary goal of the present study is to examine gender differences when considering ages of onset of risk behaviors as mediators in the relationship between child maltreatment and functioning in middle adulthood.

The Present Study

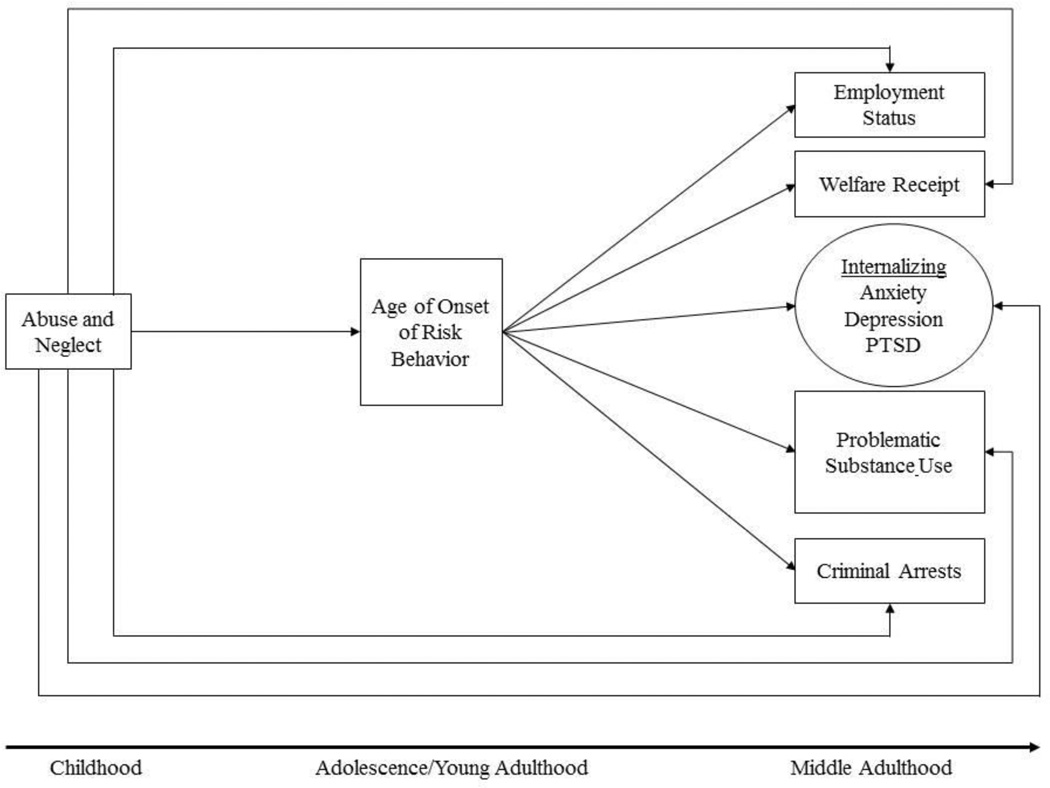

To our knowledge, previous research has not examined the extent to which the age of onset of risk behaviors may serve as a pathway or mechanism linking child maltreatment to long-term outcomes, despite repeated calls for this type of research (Piquero et al., 2007; Robins & Przybeck, 1985). Therefore, the primary goal of the present study is to examine whether child maltreatment leads to earlier initiation of specific risk behaviors (i.e., sexual intercourse, alcohol and drug use, criminal behavior), and whether these behaviors, in turn, predict maladaptive functioning in middle adulthood across a number of major domains of functioning, including socioeconomic, mental health, and behavioral problems. We hypothesized that the age of onset of each risk factor would mediate the relationship between child abuse and neglect and each of the outcomes in middle adulthood. Specifically, we hypothesize that individuals with histories of childhood abuse and/or neglect will engage in each risk behavior at an earlier age and, in turn, experience fewer employment opportunities, more reliance on public financial assistance, more internalizing and substance use problems, and more engagement in criminal behavior in middle adulthood, compared to individuals without such histories of childhood maltreatment (see Figure 1). Secondarily, given the gender differences in prevalence rates and ages of initiation of these risk behaviors and gender differences in consequences of childhood maltreatment that have been previously reported, we hypothesize that females will engage in these behaviors at a later age than males and, therefore, the mediation effect may not be as strong for females, given that some of these risk factors are considered to be developmentally normative when initiated in adulthood (i.e., sexual intercourse, alcohol use).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model depicting age of onset of risk behaviors mediating the relationship between child abuse/neglect and outcomes in middle adulthood.

Method

Design

This research is based on a cohort design study (Leventhal, 1982; Schulsinger & Mednick, 1981) in which abused and neglected children were matched with non-abused and non-neglected children and followed prospectively into adulthood. Notable features of the design include: (1) an unambiguous operationalization of child abuse and/or neglect; (2) a prospective design; (3) separate abused and neglected groups; (4) a large sample; (5) a comparison group matched as closely as possible on age, sex, race and approximate social class background; and (6) assessment of the long-term consequences of abuse and/or neglect beyond adolescence and into adulthood.

The prospective nature of the study disentangles the effects of childhood victimization from other potential confounding effects. Because of the matching procedure, subjects are assumed to differ only in the risk factor: that is, having experienced childhood neglect or sexual or physical abuse. Since it is obviously not possible to randomly assign subjects to groups, the assumption of group equivalency is an approximation. The comparison group may also differ from the abused and neglected individuals on other variables nested with abuse or neglect.

Participants

The rationale for identifying the abused and neglected group was that their cases were serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Only court substantiated cases of child abuse and/or neglect were included. Cases were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest during the years 1967 through 1971 (N = 908). To avoid potential problems with ambiguity in the direction of causality and to ensure that the temporal sequence was clear (that is, child abuse and/or neglect → subsequent outcomes), abuse and/or neglect cases were restricted to those in which children were less than 12 years of age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, bone and skull fractures, and other evidence of physical injury. Sexual abuse charges ranged from felony sexual assault to fondling or touching in an obscene manner, rape, sodomy, and incest. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents' deficiencies in child care were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time. These cases represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children.

A critical element of this design was the establishment of a comparison or control group, matched as closely as possible on the basis of sex, age, race, and approximate family socio-economic status during the time period under study (1967 through 1971). To accomplish this matching, the sample of abused and neglected cases was first divided into two groups on the basis of their age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Children who were under school age at the time of the abuse or neglect were matched with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 1 week), and hospital of birth through the use of county birth record information. For children of school age, records of more than 100 elementary schools for the same time period were used to find matches with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 6 months), same class in same elementary school during the years 1967 through 1971, and home address, within a five block radius of the abused or neglected children, if possible. Overall, there were 667 matches (73.7%) for the abused and neglected children.

Matching for social class is important because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between child abuse or neglect and later outcomes is confounded or explained by social class differences. It is difficult to match exactly for social class because higher income families could live in lower social class neighborhoods and vice-versa. The matching procedure used here is based on a broad definition of social class that includes neighborhoods in which children were reared and schools they attended. Similar procedures, with neighbourhood school matches, have been used in studies of individuals with schizophrenia (Watt, 1972) to match approximately for social class. A more recent textbook (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002) also recommended using neighborhood and hospital controls to match on variables that are related to outcomes, when random sampling is not possible. Busing was not operational at the time, and students in elementary schools in this county were from small, socioeconomically homogeneous neighborhoods.

If the control group included subjects who had been officially reported as abused or neglected, at some earlier or later time period, this would jeopardize the design of the study. Therefore, where possible, two matches were found to allow for loss of comparison group members. Official records were checked, and any proposed comparison group child who had an official record of abuse or neglect in their childhood was eliminated. In these cases (n = 11), a second matched child was selected for the control group to replace the individual excluded. No members of the control group were reported to the courts for abuse or neglect; however, it is possible that some may have experienced unreported abuse or neglect.

The first phase of the study began as an archival records check to identify a group of abused and neglected children and matched controls to assess the extent of delinquency, crime, and violence (Widom, 1989). Subsequent phases of this research involved locating and interviewing the abused and/or neglected individuals (22–30 years after the initial court cases for the abuse and/or neglect) and the matched comparison group. The present study used data from official criminal arrest records (collected 1987–1988 and 1994) and the first two follow-up in-person interviews at age 29.2 (1989–1995, N = 1,196) and 39.5 (2000–2002, N = 896). Interviews were approximately 2–3 hours long and consisted of a series of structured and semi-structured questions and rating scales. Throughout all waves of the study, the interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study, to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group, and to the participants’ group membership. Similarly, the participants were blind to the purpose of the study. Participants were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the procedures involved in this study and subjects who participated signed a consent form acknowledging that they understood the conditions of their participation and that they were participating voluntarily.

Initially, the sample was about half male (49.3%) and half female (51.7%) and about two-thirds White (66.2%) and one-third Black (32.6%). At the first interview (1989–1995), we asked participants to identify their race and ethnicity, and these self-definitions are used here. At interview 2 (2000–2002), the current sample was 47.2% male, 59.3% White, non-Hispanic, and mean age 39.50. There has been attrition associated with death, refusals, and our inability to locate individuals over the various waves of the study. However, the composition of the sample across time has remained about the same. The abuse and/or neglect group represented 56–59% at each time period; White, non-Hispanics were 59–66%; and males were 47–51% of the samples. There were no significant differences across the samples on these variables or in mean age across these phases thus far.

At the time of the first interview, the average highest grade of school completed for the sample was 11.47 (SD = 2.19). Occupational status of the sample at the time of the first interview was coded according to the Hollingshead Occupational Coding Index (Hollingshead, 1975). Occupational levels of the subjects ranged from 1 (laborer) to 9 (professional). Median occupational level of the sample was semi-skilled workers, and less than 7% of the overall sample was in levels 7–9 (managers through professionals). Thus, the sample overall is skewed and the majority of the sample falls at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum.

Variables and Measures

Child abuse and neglect

Official reports of child abuse and/or neglect, based on records of county juvenile (family) and adult criminal courts from 1967–1971, were used to operationalize maltreatment. Only court-substantiated cases involving children under the age of 12 at the time of abuse and/or neglect were included. Within the present sample of 896, 77 participants (8.6%) had documented histories of physical abuse, 67 (7.5%) had histories of sexual abuse, and 404 (45.1%) had histories of neglect. A small proportion of participants (n = 52, 5.8%) had documented histories of more than one type of maltreatment.

Potential mediators: Age of onset of risk behaviors

In the first interview, participants reported on their first experiences with alcohol, drugs, and sexual intercourse, specifically, whether or not they had ever engaged in the behavior and if so, the age at which they first engaged in this behavior. Official arrest records were collected from local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies and these records were used to determine age of first arrest. While many studies examining age of onset of risk behaviors divide participants into “early” and “late” onset groups, in the present study we elected to include age of onset as a continuous variable. This decision was made to enable us to capture more accurately the full range of ages (up to age 29) at which these behaviors were initiated, without prescribing labels about what age would be considered normative and what age would be considered “early”. In addition, utilizing the original, continuous variables avoids issues such as lost variance and reduced power (MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002). For participants who had never engaged in a specific risk behavior, the age-of-onset variable was coded as missing.

Outcomes in middle adulthood

Participants reported on their employment status, welfare receipt, internalizing symptoms, and problematic substance use during the second interview (2000 – 2002).

Employment status

Participants provided information regarding the type of work that they normally do (regardless of whether or not they were employed at the time of the interview), which was then recoded to a 5-item ordinal scale based on the Hollingshead occupational scale (Hollingshead, 1975): (1) laborer/semi-skilled (20.5%), (2) skilled (19.0%), (3) service (20.5%), (4) clerical/sales/business owner (18.3%), and (5) managerial/professional (21.8%).

Welfare receipt

As part of an assessment of economic status, participants were asked to indicate whether or not they were currently participating in a number of federal or state assistance programs (e.g., food stamps, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families [TANF], Social Security Disability Income [SSDI]). Out of 13 possible programs, participants were enrolled in a range of 0 – 6 programs (M = 0.54, SD = 1.06).

Internalizing symptoms

Three self-report measures were used to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck, 1987) is a 21-item self-report scale that asks respondents about anxiety symptoms over the past week, with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely—I could barely stand it). Anxiety symptom scores ranged from 0 to 58 (M = 9.24, SD = 10.28) and the measure demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .90). The Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item self-report scale that asks about depressive symptoms over the past week, with responses ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). Depressive symptom scores ranged from 0 to 57 (M = 12.83, SD = 11.13) this measure also demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .91). Participants reported PTSD symptoms associated with events in either childhood or adulthood using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Kessler et al., 2001). PTSD symptoms ranged from 0 to 17 (M = 7.19, SD = 4.99). These three constructs were combined into a latent variable for the main study analyses.

Problematic substance use

Substance use problems were assessed on the basis of participants’ responses to questions on the 23-item Rutgers Alcohol Problem Inventory (White & Labouvie, 1989), adapted to cover drug use problems as well as those associated with alcohol. Respondents answered yes or no to each item (e.g., “Kept using drugs or alcohol when you promised yourself not to”). Symptoms ranged from 0 – 18 (M = 2.06, SD = 3.77) and Cronbach’s alpha for the sample is .92.

Criminal behavior

Official arrest records were collected from searches through three levels of law enforcement—local, state, and federal – at two time points. The first searches were conducted between 1987–1988 (mean age = 26) and then again in June 1994 (mean age = 32). Participants with a criminal record had an average of 2.14 adult criminal arrests (SD = 4.78, range = 1 – 45).

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary descriptive analyses examined gender and race/ethnic differences in the outcome variables and the prevalence and age of onset of sexual intercourse, alcohol use, illicit drug use, and criminal behavior. Then, as is standard with mediation analyses (Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998), bivariate associations between each of the study variables were examined to assess for mediation: (a) relationships between child abuse and neglect and age of onset of each of the risk behaviors, (b) relationships between child abuse and neglect and each of the outcomes in middle adulthood, and (c) relationships between age of onset of each of the risk behaviors and outcomes in middle adulthood.

Next, using MPlus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to test full models with the mediating variables that were supported by simple regression analyses. Measurement models tested the individual factor loadings and fit of one latent outcome variables (i.e., internalizing problems in middle adulthood) and structural models tested the fit of the overall mediation effects. Multiple fit indices, as well as individual path coefficients, were used to evaluate the overall pattern of fit of the models, including the critical ratio (χ2/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; Hu & Bentler, 1998). An adequate fit is indicated by a critical ratio below 3, RMSEA of .10 or lower, and CFI and TLI values of .90 or greater (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Muller, 2003). Indirect effects were assessed via the multivariate delta method (Bishop, Fienberg, & Holland, 1975), as is standard in MPlus. Each model was examined first with the total sample and then separately by gender. Gender differences were further examined through statistical tests of equality of regression coefficients (Paternoster, Brame, Mazerolle, & Piquero, 1998). To deal with attrition across the multiple time points of the present study, full information maximum likelihood estimation was utilized to avoid biases and loss of power (Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

Results

Gender and Race/Ethnicity Differences

Differences by gender and race/ethnicity were noted in many of the outcomes. Regarding gender differences, men reported holding jobs at the lower end of the socioeconomic scale (t = 7.60, p < .001), but women reported receiving significantly more forms of public assistance than men (t = 4.65, p < .001). Women also reported significantly more symptoms of depression (t = 2.73, p < .01), anxiety (t = 3.89, p < .001), and PTSD (t = 6.30, p < .001) than men. Men experienced significantly more substance-related problems (t = 4.20, p < .001) and had significantly more extensive arrest records than women (t = 9.14, p < .001). Regarding race/ethnic differences, Black participants reported receiving significantly more forms of public assistance (t = 2.38, p < .05) and had more extensive arrest records than White participants (t = 4.03, p < .001). Therefore, gender and race/ethnicity were included as covariates in all regression analyses and structural models with the exception of models examined separately by gender, in which only race/ethnicity was controlled. In addition, respondents’ age at the first interview was included as a covariate, to control for the longer period of time available for older participants to have experienced the outcomes.

Extent of Engagement in Risk Behaviors

At the time of the first interview, the majority of participants reported engaging in sexual intercourse (97.2%), alcohol use (78.8%), and drug use (69.4%), and more than half the sample (50.4%) had a criminal arrest. Participants reported initiation of these behaviors primarily during their adolescent years, although ages of initiation ranged from childhood through the mid-30s (see Table 1). Initiation of these behaviors by some participants at very young ages prompted further examination, which revealed a relatively normal distribution of ages of onset for each risk behavior; therefore the low minimum age was not simply the result of one or two outliers. It is plausible that sexual intercourse at a very young age may be indicative of childhood sexual abuse. However, this very early age of onset of sexual intercourse was not exclusively reported by participants with known histories of abuse. Arrests at these very young ages most often involved charges of truancy, incorrigibility, or running away.

Table 1.

Prevalence and Age of Onset of Risk Behaviors (N = 1,196)

| Age of Onset (in years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Item | Year Collected | Prevalence (n) | Mean (SD) | Median | Mode | Range |

| Sexual Intercourse | How old were you when you had sexual intercourse for the first time? | 1989 – 1995 | 1,069 | 14.70 (4.09) | 15.00 | 16.00 | 5 – 30 |

| Alcohol Use | How old were you when you first had any wine, beer, or other alcohol at least once a month (for 6 months or more? | 1989 – 1995 | 943 | 17.07 (3.64) | 17.00 | 18.00 | 5 – 34 |

| Drug Use | Have you ever taken any other drugs on your own either to get high or for other mental effects [excluded alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and prescribed substances]? | 1989 – 1995 | 830 | 15.80 (3.43) | 16.00 | 16.00 | 5 – 34 |

| Criminal Arrest | Search of official records | 1987 – 988, 1994 | 603 | 18.59 (5.42) | 17.00 | 15.00 | 5 – 37 |

Compared to the controls, victims of child abuse and neglect were more likely to have ever used illicit drugs (71.4% vs. 66.7%; χ2 = 3.08, p < .10) and been arrested (56.5% vs. 42.5%; χ2 = 23.08, p < .001), but were not more likely to have ever engaged in sexual intercourse (97.2% vs. 97.5%, ns) or ever used alcohol (80.3% vs. 78.1%, ns) than controls. In terms of age of onset, individuals with documented cases of child abuse and neglect engaged in sexual intercourse at an earlier age (β = −.14, p < .001) and were first arrested at a younger age (β = −.12, p < .01) than controls (see Table 2). There were no differences between the two groups in terms of age of onset of alcohol or drug use. Child abuse and neglect significantly predicted all of the outcomes in middle adulthood (see Table 2). Table 3 shows the results of bivariate analyses of the relationships between the age of onset mediators and outcomes in middle adulthood. Results indicated that the age of onset mediators were all significantly, yet differentially related to a number of the outcomes in middle adulthood.

Table 2.

Risk Behaviors (Potential Mediators) and Outcomes for Abused/Neglected Children and Matched Controls Followed Up into Middle Adulthood Participants (N = 896)

| Child Abuse and Neglect |

Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | R2 | β | |

| Potential Mediators | ||||

| Age of Onset of Risk Behaviors | ||||

| Sexual intercourse | 14.11 (4.38) | 15.25 (3.80) | .03 | −.14*** |

| Alcohol use | 17.07 (3.81) | 17.07 (3.40) | .05 | −.01 |

| Drug use | 15.84 (3.65) | 15.75 (3.11) | .07 | .07 |

| Criminal Arrest | 18.12 (5.28) | 19.41 (5.58) | .04 | −.12** |

| Outcomes in Middle Adulthood | ||||

| Employment status | 2.92 (1.38) | 3.13 (1.49) | .08 | −.09* |

| Welfare receipt | 0.71 (1.20) | 0.34 (0.82) | .06 | .16*** |

| Internalizing Symptoms | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 10.32 (11.27) | 7.89 (8.70) | .03 | .11** |

| Depressive symptoms | 15.40 (11.65) | 10.73 (10.08) | .04 | .16*** |

| PTSD symptoms | 7.74 (5.10) | 6.51 (4.77) | .06 | .11** |

| Problematic substance use | 2.32 (4.02) | 1.73 (3.41) | .03 | .08* |

| Criminal Arrests | 2.73 (5.68) | 1.40 (3.17) | .13 | .15*** |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Italicized terms indicate latent constructs created out of the variables beneath.

Table 3.

Bivariate Relationships Between Age of Onset of Risk Behaviors and Outcomes in Middle Adulthood

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Onset Mediators | ||||||||

| 1. Sexual Intercourse | ||||||||

| 2. Alcohol Use | .27*** | |||||||

| 3. Drug Use | .29*** | .55*** | ||||||

| 4. Arrest | .08 | .13** | .07 | |||||

| Outcomes in Middle Adulthood | ||||||||

| 5. Employment Status | .09* | .09* | .07 | .07 | ||||

| 6. Welfare Receipt | −.04 | −.03 | .02 | −.04 | −.15** | |||

| 7. Internalizing Symptoms | −.15*** | −.06 | −.05 | −.12* | −.19*** | .26*** | ||

| 8. Problematic Substance Use | −.11** | −.13*** | −.12** | −.10* | −.18*** | .15*** | .38*** | |

| 9. Criminal Behavior | −.10** | −.13*** | −.06 | −.19*** | −.12** | .08* | .13*** | .20*** |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Analyses controlled for gender, race, and age.

Mediation Models

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was then used to examine whether age of onset of sexual intercourse and age of first arrest mediated the relationship between child abuse and neglect and outcomes in middle adulthood. Given that the bivariate regression analyses did not show significant associations between child abuse and neglect and age of initiation of alcohol use or illicit drug use, these factors were not examined as mediators. Before running the full models, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the fit of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD onto one latent variable measuring internalizing symptoms. The structure coefficients (β’s = .51 – .87, p’s < .001) supported this latent factor, which was significantly correlated with the other outcome variables in this study (see Table 3).

Next, the full structural models were examined, first for the total sample and then separately by gender. Separate sets of models were run for each mediator. Each model included paths directly from child abuse and neglect to the outcomes as well as the mediation paths (see earlier Figure 1). Path coefficients are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates in the Models Examining Age of Onset of Sexual Intercourse and Age of First Criminal Arrest as Mediators in the Relationship Between Child Abuse/Neglect and Outcomes in Middle Adulthood

| Total Sample | Females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | B (S.E.) | β | B (S.E.) | β | B (S.E.) | β |

| Model 1: Age of Onset of Sexual Intercourse | ||||||

| Child Abuse & Neglect → | ||||||

| Age of Onset of Sexual Intercourse | −1.12 (0.22) | −.15*** | −1.75 (0.32) | −.23*** | −0.51 (0.29) | −.07+ |

| Employment | −0.26 (0.10) | −.09* | −0.32 (0.15) | −.12* | −0.22 (0.15) | −.08 |

| Welfare Receipt | 0.34 (0.07) | .16*** | 0.42 (0.12) | .17*** | 0.23 (0.08) | .14** |

| Internalizing Problems | 2.54 (0.60) | .15*** | 2.75 (0.89) | .16** | 2.08 (0.76) | .05 |

| Problematic Substance Use | 0.50 (0.26) | .07* | 0.75 (0.32) | .11* | 0.25 (0.40) | .03 |

| Criminal Arrests | 1.35 (0.30) | .14*** | 0.64 (0.19) | .16** | 2.19 (0.57) | .18*** |

| Age of Onset of Sexual Intercourse → | ||||||

| Employment | 0.03 (0.10) | .07* | 0.02 (0.02) | .06 | 0.04 (0.02) | .10+ |

| Welfare Receipt | −0.01 (0.01) | −.02 | −0.03 (0.01) | −.08+ | −0.02 (0.01) | .07 |

| Internalizing Problems | −0.28 (0.08) | −.12*** | −0.41 (0.11) | −.18*** | −0.03 (0.11) | −.01 |

| Problematic Substance Use | −0.10 (0.03) | −.10** | −0.10 (0.04) | −.11* | −0.12 (0.06) | −.10* |

| Criminal Arrests | −0.11 (0.04) | −.08** | 0.00 (0.02) | .01 | −0.26 (0.08) | −.15** |

| Model 2: Age of First Criminal Arrest | ||||||

| Child Abuse & Neglect → | ||||||

| Age of First Criminal Arrest | −1.29 (0.45) | −.12** | 0.25 (0.82) | −.02 | −1.82 (0.53) | −.17** |

| Employment | −0.27 (0.11) | −.09* | −0.35 (0.14) | −.13* | −0.19 (0.15) | −.07 |

| Welfare Receipt | 0.34 (0.07) | .16*** | 0.47 (0.11) | .19*** | 0.20 (0.08) | .12* |

| Internalizing Problems | 2.68 (0.60) | .16*** | 3.50 (0.88) | .20*** | 1.78 (0.76) | .12* |

| Problematic Substance Use | 0.54 (0.26) | .07* | 0.92 (0.32) | .14** | 0.14 (0.41) | .02 |

| Criminal Arrests | 1.31 (0.30) | .14*** | 0.63 (0.19) | .16** | 1.86 (0.57) | .15** |

| Age of First Criminal Arrest → | ||||||

| Employment | 0.01 (0.01) | .05 | 0.00 (0.02) | .02 | 0.02 (0.02) | .09 |

| Welfare Receipt | −0.01 (0.01) | −.03 | 0.00 (0.01) | .00 | −0.01 (0.01) | −.07 |

| Internalizing Problems | −0.16 (0.08) | −.11* | −0.11 (0.13) | −.07 | −0.19 (0.08) | −.14* |

| Problematic Substance Use | −0.06 (0.03) | −.09* | −0.04 (0.04) | −.06 | −0.09 (0.04) | −.12* |

| Criminal Arrests | −0.15 (0.03) | −.17*** | −0.01 (0.02) | −.04 | −0.28 (0.06) | −.24*** |

Note.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

B = unstandardized estimate. S.E. = standard error. β = standardized estimate.

Model 1: Sexual intercourse as a mediator

The model examining age of onset of sexual intercourse as a mediator with the full sample yielded fit indices within the acceptable range (χ2(18) = 82.60; CFI = .96; TLI = .86; RMSEA = .06 [95% C.I. = .04 – .07]). The indirect effects were significant for child abuse and neglect through age of onset of sexual intercourse on internalizing symptoms (β = .02, p < .01), problematic substance use (β = .02, p < .01), and criminal arrests (β = .01, p < .05), and at the trend level, employment status (β = −.01, p < .10). When neglect cases were examined uniquely1, the results were very similar, with fit indices indicating acceptable fit (χ2(18) = 69.38; CFI = .96; TLI = .87; RMSEA = .05 [95% C.I. = .04 – .07]) and significant indirect effects for neglect through age of onset of sexual intercourse on employment status (β = −.02, p < .05), internalizing symptoms (β = .02, p < .01), problematic substance use (β = .02, p < .01), and criminal arrests (β = .01, p < .05).

When examined separately by gender, the model continued to yield fit indices within the acceptable range for both males (χ2(16) = 50.98; CFI = .94; TLI = .82; RMSEA = .06 [95% C.I. = .04 – .08]) and females (χ2(16) = 30.97; CFI = .98; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .04 [95% C.I. = .02 – .06]). However, the relationship between child abuse and neglect and age of onset of sexual intercourse remained statistically significant for females, but only significant at the trend level for males (see Table 4). A statistical test of the equality of these regression coefficients across gender supported this finding (z = 2.87, p < .01). For males, examination of the indirect effects indicated that there was no effect of child abuse and neglect on the outcomes through age of onset of sexual intercourse. However, for females, there was a significant indirect effect for child abuse and neglect through age of onset of sexual intercourse on internalizing symptoms (β = .04, p < .01) and problematic substance use (β = .03, p < .05). Again, this finding was supported by a statistical test of the equality of these regression coefficients (z = 2.89, p < .01).

Model 2: Age of first arrest as a mediator

The model examining age of first criminal arrest as a mediator with the full sample yielded fit indices within the acceptable range (χ2(18) = 85.88; CFI = .95; TLI = .85; RMSEA = .06 [95% C.I. = .05 – .07]. Examination of the indirect effects indicated that there was a significant indirect effect of child abuse and neglect through age of first criminal arrest to number of criminal arrests through middle adulthood (β = .02, p < .05), and a trend-level indirect effect for internalizing symptoms (β = .01, p < .10) and problematic substance use (β = .01, p < .10). When neglect cases were examined uniquely, the results were again similar, with fit indices indicating acceptable fit (χ2(18) = 75.01; CFI = .96; TLI = .86; RMSEA = .06 [95% C.I. = .05 – .07]) and significant indirect effects for neglect through age of first arrest on total number of criminal arrests (β = .02, p < .05), and at the trend level, internalizing symptoms (β = .02, p < .10) and problematic substance use (β = .01, p < .10).

When examined separately by gender, this model continued to yield fit indices within the acceptable range for both males (χ2(16) = 53.06; CFI = .94; TLI = .81; RMSEA = .07 [95% C.I. = .05 – .09]) and females (χ2(16) = 30.78; CFI = .98; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .04 [95% C.I. = .02 – .07]), however, the mediation effect was seen only for males. For females, the path from child abuse and neglect to the mediator was not significant (see Table 4). A statistical test of the equality of regression coefficients indicated that this gender difference was only significant at the trend level (z = 1.60, p < .10). For males, the indirect effect of child abuse and neglect through age of first arrest was significant for criminal arrests (β = .04, p < .01), but only significant at the trend level for internalizing symptoms (β = .02, p < .10) and problematic substance use (β = .02, p < .10). This indirect path was significantly different for males and females (z = 2.79, p < .01).

Discussion

Previous research has found that child abuse and neglect puts individuals at risk for a wide range of negative outcomes across the lifespan (Gilbert et al., 2009), including problem behaviors that, when initiated at a young age, are associated with long-lasting problems across multiple domains of functioning. Early engagement in sexual activity, substance use, and antisocial behavior has been associated with problems within these same domains; however, previous research has not yet examined whether early onset of risk behaviors mediates relationships between adverse experiences in childhood and maladaptive outcomes in adulthood. The present study attempted to fill this gap in knowledge using documented cases of child abuse and neglect that were followed prospectively and assessed in middle adulthood. Given that prior research has reported gender differences in a number of these risk behaviors and outcomes in middle adulthood, we examined whether different patterns emerged for males and females. We hypothesized that child abuse and neglect would be both directly related to these negative outcomes in middle adulthood and indirectly related to these outcomes through the age of onset of each risk behavior.

The results from this study indicate that abused and neglected children are more likely to engage in sexual intercourse and criminal behavior earlier than controls and that this earlier engagement in these risk behaviors mediated the relationship between child abuse and neglect and a number of outcomes in middle adulthood. However, there were noteworthy and significant gender differences. Specifically, sexual intercourse acted as a mediator only for females, with victims of child abuse and/or neglect becoming sexually active at a younger age than controls and, in turn, this led to more internalizing symptoms and substance use problems in middle adulthood. Previous research has found that adolescents with a history of either physical or sexual abuse report being more sexually active (Small & Luster, 1994) and a history of sexual abuse has been linked to earlier engagement in sexual activity (Butler & Burton, 1990). Thus, the present finding is consistent with this prior literature, but extends knowledge of this relationship by our use of a prospective long-term follow-up of children with documented cases of child abuse and neglect and suggests the important role played by the early onset of sexual intercourse in influencing later outcomes for these individuals. We also found that childhood neglect was associated with early sexual activity and, in turn, that this early age of onset of sexual intercourse predicted employment status, internalizing symptoms, problematic substance use, and criminal behavior in middle adulthood. These new results are consistent with previous work reporting associations between low family attachment and parental supervision and early sexual behaviors (Smith, 1997). Although our samples of physically and sexually abused children were too small to examine differences in patterns of these relationships by the types of abuse for males and females separately, our findings indicate that this may be an important avenue for future research.

These new findings also indicated that earlier age of first arrest (that is, early contact with the criminal justice system) was a significant mediating pathway for males, showing that abused and neglected males were arrested at a younger age than control males, and, in turn, this predicted more criminal arrests by middle adulthood. Earlier work has shown that early-onset behavior problems (e.g., delinquency, aggression, offending) are associated with chronic, severe antisocial behavior in adolescence and adulthood (Moffit, 1993). However, the reasons for this are not clear and explanations have ranged from environmental (Ingoldsby & Shaw, 2002) to familial (Dishion et al., 2007), genetic (D’Onofrio et al., 2007), or systemic biases (Piquero, Moffitt, & Lawton, 2005). In addition, earlier age of first arrest (and associated contact with the justice system) mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and problems with anxiety, depressive symptoms, and substance use in middle adulthood for males, indicating that early antisocial behavior affects other domains of functioning in later life.

Regardless of exposure to child abuse or neglect, the results of this study also demonstrate that early initiation of risk behaviors has a significant impact on outcomes in middle adulthood. Our findings suggest that those who are sexually active at a younger age are more likely to suffer from internalizing and substance use problems in middle adulthood and are more likely to have more extensive arrest histories. Those who engage in alcohol and drug use at a younger age are likely to report more drug use and more problems associated with substance use and more extensive arrest histories in middle adulthood than those who begin using alcohol or drugs later on in life.

Our finding that childhood maltreatment did not impact the age of initiation of substance use is surprising, given that previous research has found that physical and sexual abuse are associated with earlier use of drugs and alcohol (e.g., Hawke et al., 2000). Interestingly, in our sample, controls reported using illicit drugs at a younger age than victims of childhood abuse and/or neglect, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. Furthermore, in earlier research (Widom, Ireland, Glynn, 1995), we did not find that abuse and neglect was associated with higher rates of alcohol abuse and/or dependence diagnoses at the time of the first interview, a finding that might be explained by a saturation effect. Alternatively, it may be that factors that remain unaccounted for in the present study explain more of the variance in age of first substance use. Given that genetic and other environmental factors, such as parental and peer substance use or parental monitoring, have been associated with early substance use (e.g., Hopfer, Crowley, & Hewitt, 2003), future research that examines these as mediators or moderators in the relationship between child maltreatment and the age of onset of substance use may help to explain the findings in the present study.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study has a number of strengths, there are several limitations that warrant attention. First, because these are court-documented cases of abuse and neglect, these findings may not be generalizable to cases that are not reported to authorities or cases of abuse and neglect in middle or upper class families. Second, for the participants who experienced sexual abuse in childhood, their first experiences of sexual intercourse may have involved abuse. While it was not possible for us to determine whether participants’ reports of their age of initiation of sexual intercourse included incidences of sexual abuse, we repeated the mediation analyses without the victims of sexual abuse and the results did not differ. Third, it is possible that participants’ self-reports of age of onset of each of the risk behaviors may suffer from retrospective bias (with the exception of first criminal arrest, which was collected via official records). Although retrospective bias was avoided regarding child abuse/neglect due to our reliance on official records, it is possible that participants in the control group were exposed to unreported abuse and/or neglect, thus potentially diluting the significance of our findings. In addition, it was not possible to determine whether participants lost to follow-up differed in any of the mediators or outcomes from those who participated in all waves of the study. Finally, this study did not consider other potential mediators or moderators that may account for significant variance in the relationships examined, such as other environmental, familial, genetic, or individual-level factors. Future research may build on this study by considering the influences of other potentially relevant factors, such as parental monitoring and supervision or child temperament, to ensure that the results found in the present study are not spurious.

This study has expanded current knowledge by identifying associations between early initiation of risk behavior in one domain and later, continuing problems in different domains. These findings suggest that early initiation of specific risk behaviors may have more wide-ranging negative consequences than are typically considered during intervention or treatment. Our finding that child abuse and neglect influences early initiation of sexual intercourse among females and, in turn, predicts symptoms of depression and anxiety, problematic substance use, and to a lesser extent whether they receive financial assistance from federal or state programs in middle adulthood, suggests that interventions should be multifaceted. For girls with histories of maltreatment who engage in early initiation of sexual intercourse, preventive interventions might target effective coping mechanisms that are protective against anxiety, depressive symptoms, and substance abuse and provide guidance on employment opportunities. Based on our findings, males may also benefit from multifaceted interventions, such as those that not only attempt to reduce externalizing behaviors among boys with early problem behaviors, but also provide education on effective coping techniques to buffer against anxiety, depressive symptoms, and substance abuse.

Conclusion

While significant prior research has documented the link between early engagement in risk behaviors and later domain-specific problems, sparse research has attempted to examine other factors that may play a role in this association. The results of this study highlight the important role that child abuse and neglect plays in relation to early-onset risk behaviors and later maladaptive functioning across multiple domains. Victims of childhood abuse and neglect are more likely to engage in early-onset sexual activity and to be arrested at an earlier age compared to non-maltreated youths. By middle adulthood, individuals with histories of childhood abuse and neglect experience more emotional, behavioral, and financial difficulties. We identified important gender differences in these relationships, which have direct relevance to the development of intervention and treatment efforts to buffer the maladaptive effects of both child maltreatment and early engagement in risk behavior. For females, child abuse and neglect leads to earlier-onset sexual behavior, which leads to financial, emotional, and substance use problems. For males, child abuse and neglect leads to earlier age of onset of first arrest (and contact with the justice system), which is linked to continued antisocial behavior, as well as emotional and substance use problems. The impact of early-onset risk behaviors across multiple domains indicates that intervention and treatment programs should be multifaceted to target all areas of maladaptive functioning. Although this study overcame a number of important limitations of previous research on early-onset risk behaviors, future research is needed to understand the potential impacts of genetic and environmental factors, other than child abuse and neglect that may help to explain maladaptive outcomes in adulthood that many abused and neglected children manifest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (HD40774, HD072581), NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033 and 89-IJ-CX-0007), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Points of view are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the United States Department of Justice or National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Jacqueline M. Horan, Ph.D., is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at John Jay College of Criminal Justice of the City University of New York. She received her Ph.D. in applied developmental psychology from Fordham University. Her research focuses on examining the environmental influences and long-term consequences of engagement in problem behaviors across the lifespan, with specific attention to identification of areas of early intervention.

Cathy Spatz Widom, Ph.D., is a Distinguished Professor in the Psychology Department at John Jay College and a member of the Graduate Center faculty, City University of New York. Since 1986, she has been studying the long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect, with a particular focus on the cycle of violence.

Footnotes

Physical and sexual abuse could not be examined separately due to the relatively small sample sizes of these subgroups

Authors’ Contributions

CSW collected the data used in this study as part of a larger prospective, longitudinal study examining the negative consequences of child abuse and neglect on developmental outcomes across the lifespan. JMH conceived of this specific study that uses these data, with CSW providing guidance and feedback to clarify research questions, hypotheses, and study design. JMH conducted the literature review, ran the study analyses, and drafted the manuscript. CSW extensively revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and provided feedback on analytic revisions. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Allgood S, Mustard DB, Warren RS. The impact of youth criminal behavior on adult earnings. Athens, GA: Unpublished manuscript, University of Georgia; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Beck Anxiety Inventory. Philadelphia, PA: The University of Pennsylvania, Center for Cognitive Therapy; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop YMM, Fienberg SE, Holland PW. Discrete multivariate analysis: Theory and practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Randall CL. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1999;22(2):241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Chen H, Smailes E, Johnson JG. Sexual trajectories of abused and neglected youths. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25(2):77–82. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JR, Burton LM. Rethinking teenage childbearing: Is sexual abuse a missing link. Family Relations. 1990:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenal CA, Adell MN. Factors associated with problematic alcohol consumption in schoolchildren. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;(27):425–433. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Richter DL, Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, Vincent ML. Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. Journal of School Health. 1994;64(9):372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Widom CS. Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15(2):111–120. doi: 10.1177/1077559509355316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79(5):1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Slutske WS, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, Harden KP, Heath AC, Martin NG. Intergenerational transmission of childhood conduct problems: a Children of Twins Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):820–829. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenrode J, Laird M, Doris J. School performance and disciplinary problems among abused and neglected children. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(1):53. [Google Scholar]

- Eckenrode J, Zielinski D, Smith E, Marcynyszyn LA, Henderson J, Charles R, Olds DL. Child maltreatment and the early onset of problem behaviors: Can a program of nurse home visitation break the link? Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):873–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Yates T, Appleyard K, Van Dulmen M. The long-term consequences of maltreatment in the early years: A developmental pathway model to antisocial behavior. Children's Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice. 2002;5(4):249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8(3):430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, John Horwood L, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: The consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(8):837–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Dishion TJ. Predictors of early initiation of sexual intercourse among high-risk adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23(3):295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10(2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawke JM, Jainchill N, Leon GD. The prevalence of sexual abuse and its impact on the onset of drug use among adolescents in therapeutic community drug treatment. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2000;9(3):35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer CJ, Crowley TJ, Hewitt JK. Review of twin and adoption studies of adolescent substance use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(6):710–719. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046848.56865.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SM, Garcia M, Sinha R. Gender specific associations between types of childhood maltreatment and the onset, escalation and severity of substance use in cocaine dependent adults. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32(4):655–664. doi: 10.1080/10623320600919193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS. Neighborhood contextual factors and early-starting antisocial pathways. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5(1):21–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1014521724498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Smailes EM, Cohen P, Brown J, Bernstein DP. Associations between four types of childhood neglect and personality disorder symptoms during adolescence and early adulthood: Findings of a community-based longitudinal study. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14(2):171–187. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N. Data analysis in social psychology. The handbook of social psychology. 1998;1(4):233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, Koch JR, Laska EM, Leaf PJ, Wang PS. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research. 2001;36(6 Pt 1):987. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston S, Raghavan C. The relationship of sexual abuse, early initiation of substance use, and adolescent trauma to PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(1):65–68. doi: 10.1002/jts.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DS, Sampson RJ. Juvenile arrest and collateral educational damage in the transition to adulthood. Sociology of Education. 2013;86(1):36–62. doi: 10.1177/0038040712448862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Does physical abuse in early childhood predict substance use in adolescence and early adulthood? Child Maltreatment. 2010;15(2):190–194. doi: 10.1177/1077559509352359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal JM. Research strategies and methodologic standards in studies of risk factors for child abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1982;6:113–123. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(82)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):19. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazerolle P, Brame R, Paternoster R, Piquero A, Dean C. Onset age persistence, and offending versatility: Comparisons across gender. Criminology. 2000;38(4):1143–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence: Revisited 6 years later. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(4):390. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100(4):674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: (1998–2012). [Google Scholar]

- O'Neil KA, Conner BT, Kendall PC. Internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in youth: Comorbidity, risk, temporal order, and implications for intervention. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(1):104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajer KA. What happens to “bad” girls? A review of the adult outcomes of antisocial adolescent girls. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(7):862–870. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology. 1998;36(4):859–866. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Blumstein A. Key issues in criminal career research: New analyses of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR, Moffitt TE, Lawton B. Race and crime: The contribution of individual, familial, and neighborhood level risk factors to life-course-persistent offending. In: Hawkins D, Kempf-Leonard K, editors. Our Children, Their Children: Race, Crime, and the Juvenile Justice System. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen T, Lyyra AL, Pulkkinen L. Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: a follow-up study from age 8–42 for females and males. Addiction. 2005;100(5):652–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and long-term intellectual and academic outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18(8):617–633. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Przybeck TR. Age of onset of drug use as a factor in drug and other disorders. Etiology of drug abuse: Implications for prevention. NIDA Research Monograph. 1985;56:178–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KL, Teiljohann SK, Price JH. Predictors of sixth graders engaging in sexual intercourse. Journal of School Health. 1999;69(9):369–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1999.tb06431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. A life-course view of the development of crime. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2005;602(1):12–45. [Google Scholar]

- Schulsinger F, Mednick SA, Knop J. Longitudinal research: Methods and uses in behavioral sciences. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Luster T. Adolescent sexual activity: An ecological, risk-factor approach. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56(1):181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA. Factors associated with early sexual activity among urban adolescents. Social Work. 1997;42(4):334–346. doi: 10.1093/sw/42.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Thornberry TP. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology. 1995;33(4):451–481. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeten G. Who will graduate? Disruption of high school education by arrest and court involvement. Justice Quarterly. 2006;23(4):462–480. [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Levy-Storms L, Sucoff CA, Aneshensel CS. Gender and ethnic differences in the timing of first sexual intercourse. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(3):121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt NF. Longitudinal changes in the social behavior of children hospitalized for schizophrenia as adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1972;155:42–54. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59(3):355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1223–1229. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Ireland T, Glynn PJ. Alcohol abuse in abused and neglected children followed-up: Are they at increased risk? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1995;56(2):207–217. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Kuhns JB. Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(11):1607–1612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Marmorstein NR, White HR. Childhood victimization and illicit drug use in middle adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(4):394. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]