Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Intestinal ischemia/reperfusion often leads to acute lung injury and multiple organ failure. Ischemic preconditioning is protective in nature and reduces tissue injuries in animal and human models. Although hematimetric parameters are widely used as diagnostic tools, there is no report of the influence of intestinal ischemia/reperfusion and ischemic preconditioning on such parameters. We evaluated the hematological changes during ischemia/reperfusion and preconditioning in rats.

METHODS:

Forty healthy rats were divided into four groups: control, laparotomy, intestinal ischemia/reperfusion and ischemic preconditioning. The intestinal ischemia/reperfusion group received 45 min of superior mesenteric artery occlusion, while the ischemic preconditioning group received 10 min of short ischemia and reperfusion before 45 min of prolonged occlusion. A cell counter was used to analyze blood obtained from rats before and after the surgical procedures and the hematological results were compared among the groups.

RESULTS:

The results showed significant differences in hematimetric parameters among the groups. The parameters that showed significant differences included lymphocyte, white blood cells and granulocyte counts; hematocrit; mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; red cell deviation width; platelet count; mean platelet volume; plateletcrit and platelet distribution width.

CONCLUSION:

The most remarkable parameters were those related to leukocytes and platelets. Some of the data, including the lymphocyte and granulocytes counts, suggest that ischemic preconditioning attenuates the effect of intestinal ischemia/reperfusion on circulating blood cells. Our work contributes to a better understanding of the hematological responses after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion and IPC, and the present findings may also be used as predictive values.

Keywords: Ischemic Reperfusion Injury, Ischemic Preconditioning, Systemic Inflammatory Response, Intestinal Ischemia, Hemocytometry, Superior Mesenteric Artery Occlusion

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic injury results from the interruption of blood flow and causes damage to active tissues; ischemic reperfusion injury (IRI) occurs after the restoration of blood flow, leading to additional tissue injury 1. In 1986, Parks and Granger 2 reported that reperfusion is more harmful than ischemia alone. In particular, the tissue damage that is caused by ischemia and reperfusion in the intestine is associated with high morbidity and mortality in surgical patients. IRI occurs in cases of abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery, hemorrhagic shock, acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI), strangulated hernia, neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis, cardiopulmonary bypass and organ transplantation 3. Among the internal organs, the intestine is most sensitive to IRI 1. Intestinal IRI can lead to damage in the intestinal mucosa and the release of various inflammatory mediators, potentially resulting in the development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and further leading to multiple organ failure (MOF), especially acute lung injury (ALI) 4-7. Ischemia-reperfusion causes local and systemic changes in hemodynamics, endothelial function, microcirculation, fluid equilibrium and metabolic homeostasis while also inducing the complement and inflammatory pathways 8-14. In an attempt to attenuate this damage, several treatment modalities have been applied in various animal models of IRI, such as hypothermia, antioxidants, ischemic preconditioning (IPC) and modulation of inflammatory mediators and adhesion molecules. Among these approaches, IPC seems to be the most promising against reperfusion injury, as it increases the bowel's tolerance against the damage caused by ischemia followed by reperfusion 15-17.

In 1986, Murry et al. introduced the concept of IPC as short episodes of ischemia followed by short periods of reperfusion preceding a prolonged ischemia; this approach was shown to protect organs against subsequent longer ischemia 18. IPC of the intestine was first described by Hotter et al. in 1996 19 and subsequent studies have confirmed this phenomenon. Studies in shock models show that IPC before intestinal ischemia causes a significant reduction in the inflammatory response in the lungs and intestinal injuries due to hemorrhagic shock 20. However, the precise mechanism by which IPC confers protection to the intestine remains unclear.

Blood is the most accessible component of the vertebrate body fluid system and has frequently been examined to assess physiological status 21. Hematimetric parameters have long been used as diagnostic tools for a large number of diseases, such as leukemias, anemias and infectious diseases. However, few studies have collectively addressed the prognostic values of these parameters using multivariate analysis and to our knowledge, no studies have addressed IPC. The purpose of this study was to obtain a basic knowledge of the hematological factors after IRI and IPC in rats. In this prospective study, we evaluated the significance of routine blood parameters after intestinal ischemia and preconditioning in rats, the results of which could help in the early diagnosis of IRI and in understanding how IPC affects blood components.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental subjects and sample collection

Male Wistar rats without inflammatory disease and weighing 250–350 g were collected from the animal house of the Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP), São Paulo State, Brazil. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of FMUSP (Protocol No. 8186) for the use of rats as experimental subjects. The animals were provided access to food and water ad libitum until the time of the experiment.

Experimental groups

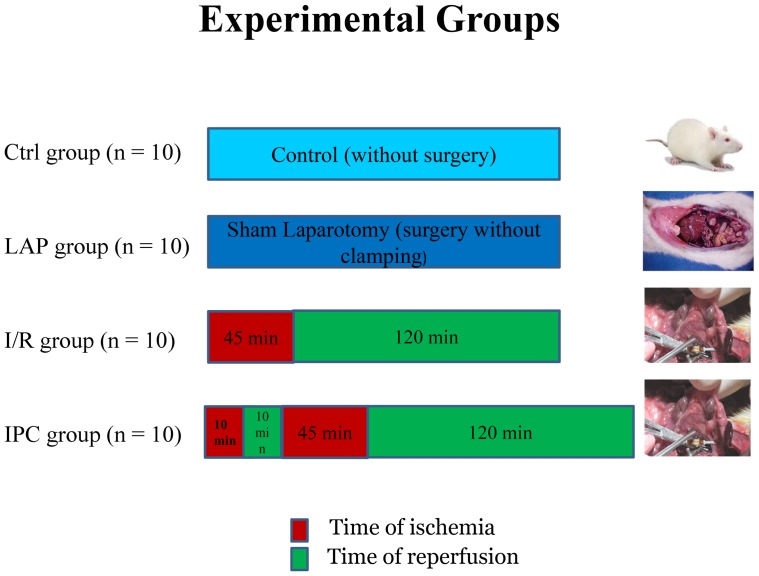

Forty rats were randomly allocated into the following four groups (Figure 1), where n represents the number of animals per group:

Figure 1.

Experimental groups and their times of ischemia and reperfusion, where n represents the number of animals per group.

1- The control group (C) (n = 10), without any surgical procedure.

2- The sham laparotomy group (LAP) (n = 10), without clamping of any artery, but receiving the same surgical procedure except for the clamping.

3- Ischemia/reperfusion (IR) group (n = 10), submitted to superior mesenteric artery occlusion (SMAO) for 45 min followed by 120 min of reperfusion.

4- Ischemic preconditioning (IPC) group (n = 10), submitted to a 10-min period of SMAO followed by 10-min reperfusion immediately before 45 min of ischemia and 120 min of reperfusion, as in the IR group.

Hematological analyses

We collected 20 µl of blood from the tails of all animals before and after surgery and injected the samples into a veterinary automated cell counter (BC-2800Vet, Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Nanshan, China). The analyzed hematimetric parameters included the total erythrocyte count (RBC), total white blood cell (WBC) count, hematocrit (HCT) level, hemoglobin (Hb) concentration, erythrocyte indices as mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), platelet (PLT) count, mean platelet volume (MPV), platelet distribution widths (PDW), plateletcrit (PCT) and WBC differential count 22,23.

Surgical procedures

The surgical procedures were performed in the Laboratory of Surgical Physiopathology (LIM-62), department of Surgery, FMUSP. Rats from all of the groups were anesthetized with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of sodium pentobarbital (45 mg/kg) and ketamine (80 mg/kg) + xylazine (7 mg/kg) and their core body temperatures were maintained at 37°C. After midline laparotomy, the superior mesenteric artery was isolated near its aortic origin. During this procedure, the intestinal tract was placed between gauze pads that had been soaked with warmed 0.9% NaCl solution. In rats from the IR group, the superior mesenteric artery was clamped, resulting in total occlusion of the artery for 45 min. After the time of occlusion, the clamps were removed and blood samples were collected from the tail after 120 min of reperfusion. In the rats of the IPC group, the ischemic procedure described above was preceded by 10 min of clamping followed by 10 min of reperfusion.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, the data were first checked for normality by applying the D′Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test. The data were normalized and outliers were removed, based on the Thompson tau technique; then, normality was reconfirmed with the above-mentioned normality test. Variance analysis (one-way ANOVA) was used to determine the difference between the groups and the Tukey-Kramer test was used to compare and determine the means that differed significantly from each other using the Graph Pad Prism program (V.6.0c). Values with p<0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

The hematological parameters of the control, laparotomy, ischemia/reperfusion and IPC groups are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Table 1.

Hematological analyses, expressed as the mean±standard deviation, median and range (min. - max.) of the four groups.

| Parameters | Control group | Laparotomy group | Ischemia/Reperfusion group | Preconditioning group | ||||||||

| Mean ± std dev | Median | Range Min - Max | Mean ± std dev | Median | Range Min - Max | Mean ± std dev | Median | Range Min - Max | Mean ± std dev | Median | Range Min - Max | |

| WBC (109/L) | 10.27±2.04 | 10.85 | 6.8-12.3 | 14.71±3.4 | 15.75 | 8.6-18.7 | 18.13±5.16 | 19.1 | 11.8-15.75 | 16.39±4.67 | 15.7 | 8.7-23.2 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 6.79±1.59 | 7.2 | 4.1-8.8 | 5.6±1.42 | 5.3 | 3.5-7.7 | 5.65±1.28 | 5.65 | 3.7-8.8 | 5.61±2.24 | 5.05 | 3.9-11.6 |

| Monocytes (109/L) | 0.31±0.07 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.4 | 0.6±0.28 | 0.5 | 0.3-1.2 | 0.71±0.29 | 0.6 | 0.4-0.6 | 0.57±0.19 | 0.6 | 0.3-0.8 |

| Granulocytes (109/L) | 3.17±0.59 | 3.1 | 2.3-3.9 | 8.51±2.11 | 9.15 | 4.7-10.7 | 13.36±6.31 | 12.85 | 5-9.15 | 10.21±3.7 | 9.85 | 4.5-17.6 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 64.76±2.96 | 65.1 | 60-70.8 | 38.26±4.98 | 39.95 | 30.3-45.1 | 28.47±5.23 | 27.35 | 22-70.8 | 36.33±8.19 | 34.85 | 26.7-51.8 |

| Monocytes (%) | 3.25±0.36 | 3.1 | 2.9-3.9 | 3.68±0.6 | 3.6 | 2.9-4.7 | 3.36±0.28 | 3.35 | 3-3.9 | 3.81±0.43 | 3.85 | 3.2-4.7 |

| Granulocytes (%) | 32.1±2.86 | 31.65 | 26.2-37.1 | 57.63±4.61 | 56.75 | 51.1-65.9 | 67.87±5.74 | 69.5 | 57.5-57.63 | 59.89±8.25 | 61.45 | 44.5-69.3 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 6.528±0.55 | 6.58 | 5.49-7.52 | 7.38±0.72 | 7.65 | 6.1-8.3 | 7.66±0.52 | 7.665 | 6.88-7.65 | 7.32±1.38 | 7.63 | 4.62-9.58 |

| Hb (g/L) | 128±6.94 | 126.5 | 120-142 | 138.5±12.03 | 138.5 | 120-156 | 143.3±7.69 | 144 | 134-142 | 141±20.02 | 147.5 | 107-167 |

| HCT (%) | 40.83±1.86 | 40.45 | 38.8-44.4 | 44.63±3.63 | 44.95 | 38.7-49.8 | 47.07±2.61 | 46.85 | 43.3-44.95 | 45.14±6.31 | 47.65 | 34.2-54.2 |

| MCV (fL) | 61.39±2.46 | 61.1 | 57.2-65.1 | 60.41±1.95 | 59.95 | 58-63.7 | 61.57±2.34 | 61.2 | 58.2-65.1 | 60.8±2.39 | 60.75 | 56.6-64.7 |

| MCH | 19.16±0.75 | 19.15 | 17.6-20.3 | 18.6±0.67 | 18.6 | 17.8-19.7 | 18.7±0.8 | 18.8 | 17.5-20.3 | 18.98±0.73 | 19.05 | 17.4-20.1 |

| MCHC (g/L) | 312.8±4.61 | 312.5 | 307-320 | 308.7±5.89 | 308.5 | 301-320 | 304.1±5.36 | 302.5 | 297-320 | 312.7±7.12 | 313.5 | 303-325 |

| RDW (%) | 11.46±0.72 | 11.2 | 10.7-12.7 | 11.96±0.65 | 11.95 | 10.5-12.9 | 12.52±1.35 | 12.15 | 11-12.7 | 12.87±1.32 | 12.7 | 11.5-15.2 |

| PLT (109/L) | 746.6±148.32 | 785.5 | 529-943 | 837.3±92.71 | 828 | 679-1024 | 867.2±154.25 | 800.5 | 734-943 | 653.1±248.34 | 665 | 341-1135 |

| MPV (fL) | 5.3±0.2 | 5.3 | 5-5.7 | 5.45±0.18 | 5.45 | 5.1-5.8 | 5.64±0.2 | 5.6 | 5.4-5.7 | 5.93±0.33 | 5.95 | 5.5-6.4 |

| PDW | 16.1±0.24 | 16.05 | 15.8-16.5 | 16.15±0.26 | 16.15 | 15.8-16.7 | 16.13±0.13 | 16.15 | 15.9-16.5 | 16.86±0.68 | 16.9 | 15.9-18.1 |

| PCT (%) | 0.3946±0.08 | 0.412 | 0.275-0.49 | 0.46±0.03 | 0.456 | 0.418-0.52 | 0.49±0.09 | 0.441 | 0.401-0.49 | 0.3763±0.12 | 0.3945 | 0.218-0.578 |

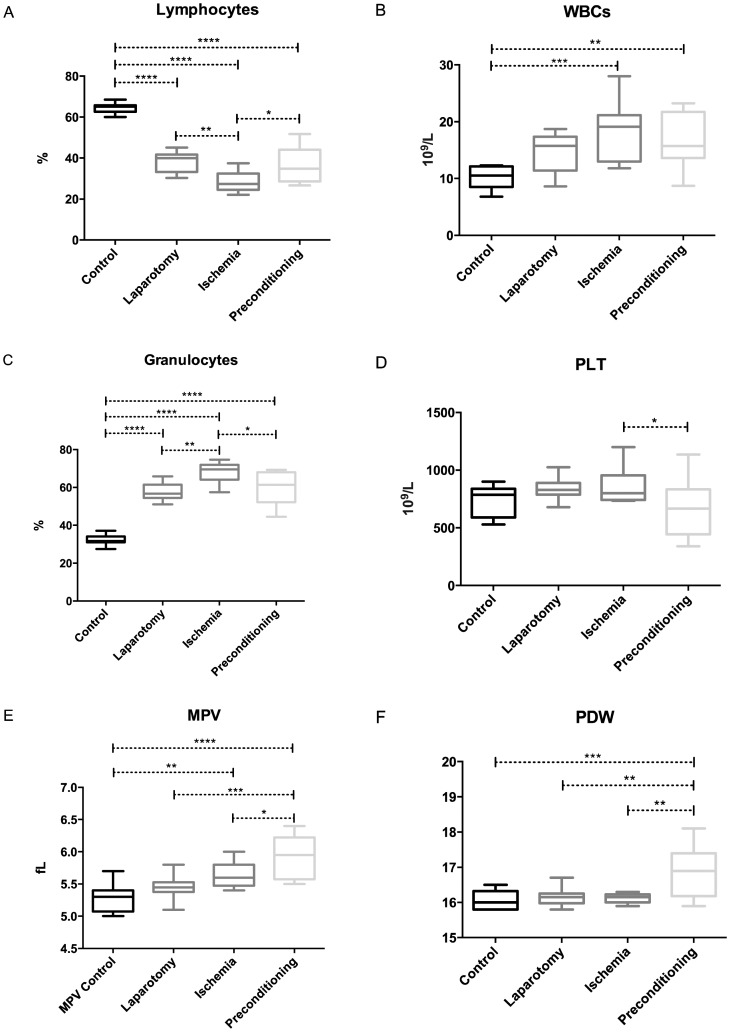

All of the surgical groups (LAP, IR and IPC) showed a remarkably smaller amount of lymphocytes than did the control group. Among the surgical groups, the IR group showed a decrease in lymphocyte count (p = 0.0021) compared with the LAP group; however, an increase was noted in the IPC group (p = 0.0171) compared with IR group (Figure 2-A).

Figure 2.

Distribution of the hematimetric parameters in the four experimental groups. (A) Lymphocyte count, (B) WBC count (C) Granulocyte count, (D) Platelet count, (E) MPV and (F) PDW. (***p<0.001; **p<0.001 to 0.01; *p<0.01 to 0.05).

The WBC counts showed a significant increase in both the IR (p = 0.0005) and the IPC (p = 0.0074) groups compared with the control group (Figure 2-B). The elevation in WBCs was more prominent in the IR group than in the IPC group. A significant increase in the granulocyte count was observed in the LAP, IR and IPC groups compared with the controls; there was also an increase in the IR group compared with the LAP group (p = 0.0015), whereas the IPC group showed a significant reduction (p = 0.0168) compared with the IR group, almost approaching the level of the LAP group (Figure 2-C).

Platelets showed a significant difference between the IR and IPC groups. The PLT counts were higher (p = 0.0340) in the IR group than in the IPC group (Figure 2-D) and the MPV also showed a significantly increased value in the IR (p = 0.0096) and IPC (p = <0.0001) groups compared with the controls. In preconditioned rats, the MPV was higher than that in LAP (p = 0.0004) and IR rats (p = 0.0485) (Figure 2-E). The PDW was significantly greater in IPC rats compared to all of the other groups. The p-values for the IPC group compared with the control, LAP and IR groups are 0.0003, 0.0015 and 0.0011, respectively (Figure 2-F).

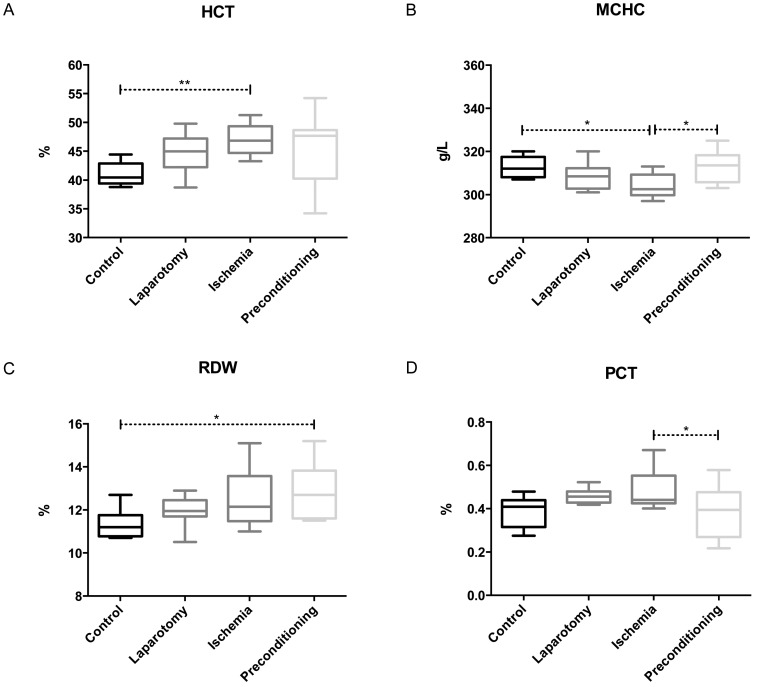

The levels of monocytes, RBCs, Hb, MCV and MCH were not influenced significantly in any experimental group. The HCT level was increased (p = 0.0082) in the IR group compared with the control group (Figure 1-A, supplementary). The MCHC was decreased in the IR group (p = 0.0111) compared with the controls, whereas there was an increase in the MCHC value in the IPC group (p = 0.0111) compared with the IR group, which restored the MCHC value to a normal level (Figure 1-B, supplementary). The red cell deviation width was higher (p = 0.0152) in the IPC group than the control group, although no other group showed a significant difference (Figure 1-C, supplementary). Both the IR and IPC groups showed significant differences regarding their PCT levels, whereas the remaining groups did not show any significant differences. The PCT level was higher (p = 0.0264) in the IR group compared with the IPC group (Figure 2-D).

Supplementary Figure 1.

supplementary. Distribution of hematimetric parameters in the four experimental groups. (A) HCT, (B) MCHC, (C) Red cell distribution width and (D) PCT. (**p<0.001 to 0.01; *p<0.01 to 0.05).

DISCUSSION

IPC has been studied as a protective strategy against IRI in intestinal models 19,20. In humans, prolonged jejunal ischemia (45 min) followed by reperfusion results in intestinal barrier integrity loss, which is accompanied by a significant translocation of endotoxins. These phenomena result in an inflammatory response that is characterized by complement activation, endothelial activation, neutrophil sequestration and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators into circulation 24. A comparison of the effect of IR and IPC on blood parameters has not been made using the 45-min SMAO model in rats. Lymphocyte loss and dysfunction have been consistently reported in animal models of both SIRS and sepsis 25 and preventing lymphocyte dysfunction, specifically lymphocyte apoptosis following sepsis, has been shown to improve survival after sepsis 26. Recently, a decrease in the lymphocyte percentage was observed following IR and local and remote IPC in a rat model with temporary supraceliac aortic clamping 27. IPC also prevented lymphocyte loss compared with that observed in the IR group in our study.

We observed a significant increase in the WBC count after IR. Postoperative leukocytosis represents a normal physiologic response to surgery 28. However, an augmentation in the WBC count has been viewed as a predictor of ischemic stroke 29. This increase is due to the marked elevation of leukocyte activation, as previously described in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in dogs 30. The increased number of granulocytes after ischemic strokes leads to tissue damage, as these cells are implicated in the early responses of the hemostatic and inflammatory processes 31. Intestinal ischemia is characterized by the production of cytokines 32 and the sequestration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) into the ischemically damaged tissue. The complement system also contributes to the attraction of neutrophils to ischemically damaged areas 33, where neutrophil-released myeloperoxidase (MPO) and other proinflammatory mediators further contribute to IR-induced tissue damage 34. Figure 2-C clearly shows a significant reduction in circulating granulocytes of the IPC group compared with the IR group, suggesting a protective aspect of IPC.

With the exception of the MCHC values, our results concerning RBCs, Hb, MCV, MCH and HCT are similar to those of a study using a canine model to investigate limb IR, with or without cooling 35. Dehydration during surgery or fluid sequestration due to edema can result in a higher-than-normal HCT level 36. This increase was more prominent in the IR group and showed no significant difference in any other group. Similarly, an increase in HCT was observed in the IR compared with local IPC and remote IPC groups in a similar model using temporary supraceliac aortic clamping 27.

Platelets also participate in ischemic strokes 37 and IR-mediated tissue damage 38 through the modulation of leukocyte function and the generation of free radicals and proinflammatory mediators, such as thromboxane (TxA2), leukotrienes, serotonin, platelet factor-4 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) 39,40. Similar to leukocytes, the expression of P-selectin on the platelet surface contributes to rolling and firm adherence to the vascular endothelium and in the interaction with leukocytes during post-ischemic reperfusion, resulting in increased expression of adhesion molecules, the generation of superoxide and the phagocytic activity of leukocytes 39,41. The inhibition of platelet adhesion by the administration of an anti-fibrinogen antibody was shown to decrease short-term liver injury after ischemia. In addition, platelet-derived serotonin is a mediator of tissue repair after hepatic normothermic ischemia in mice 42,43. We observed a significant decrease in platelets in the IPC group compared with the IR group. However, the role of platelets in the progression of tissue damage after IR injury remains unclear. A recent study showed that platelet-deficient mice showed significant reductions in damage to their villi in response to IR compared with mice with normal platelet counts 44.

Previous studies showed that the MPV was higher when there was destruction of platelets associated with inflammatory bowel disease 45, whereas other studies showed that the MPV was not associated with stroke severity or functional outcomes 46. The activation of platelets leads to morphologic changes, including pseudopodia formation and the development of a spherical shape. Platelets with an increased number and size of pseudopodia differ in size, possibly affecting the PDW. Indeed, we found an inverse relationship between the PLT count and MPV value after IR and IPC, which suggests that IPC lowers the PLT count but increases the MPV value. However, a recent study in patients who underwent surgical intervention for acute mesenteric ischemia showed an increase in MPV and a decrease in PLT count in non-surviving patients compared with surviving patients 47. In the IR group, we found an increase in the PLT count and a decrease in the MPV value, in contrast to this previous study. This discrepancy could be attributed to different occlusion models because AMI patients can present partial vascular occlusions that last for less-precise amounts of time. In addition, we cannot correlate this change with mortality rate, as the model involving 45 min of intestinal ischemia in rats has been considered to be free of mortality 48, whereas the ischemic period and severity varies among clinical conditions, leading to higher morbidity and mortality. For example, AMI has an overall mortality of 60% to 80% and the reported incidence increases over time 49,50, mostly because of the continued difficulty in recognizing this condition 50. The effect of IPC on these parameters with AMI requires further validation in humans.

In summary, our results demonstrate that IPC before intestinal IR provoked significant alterations in hematimetric parameters in the IPC group compared with that in the IR group, mainly comprising decreases in the granulocyte count and PCT count and increases in the lymphocyte count and the MPV.

The results of the present study indicate that 10 min of IPC before 45 min of intestinal IR alter the hematimetric parameters, suggesting that IPC attenuates the effect of IR in circulating blood cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge TWAS, CNPq, CAPES, FAPESP, FAP-DF and FUB-UnB for financial support. We also thank Prof. Dr. Paulina Sonnomiya from the Laboratory of Cardio-Pneumology (LIM-11) of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo LIM11 for allowing access to the hemocytometer.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yamamoto S, Tanabe M, Wakabayashi G, Shimazu M, Matsumoto K, Kitajima M. The role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the rat small intestine. J Surg Res. 2001;99(1):134–41. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks DA, Granger DN. Contributions of ischemia and reperfusion to mucosal lesion formation. Am J Physiol. 1986;250(6 Pt 1):G749–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.250.6.G749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collard CD, Gelman S. Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and prevention of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Anesthesiology. 2001;94(6):1133–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200106000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceppa EP, Fuh KC, Bulkley GB. Mesenteric hemodynamic response to circulatory shock. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2003;9(2):127–32. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koksoy C, Kuzu MA, Kuzu I, Ergun H, Gurhan I. Role of tumour necrosis factor in lung injury caused by intestinal ischaemia-reperfusion. Br J Surg. 2001;88(3):464–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao F, Eppihimer MJ, Young JA, Nguyen K, Carden DL. Lung neutrophil retention and injury after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion. Microcirculation. 1997;4(3):359–67. doi: 10.3109/10739689709146800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teles LM, Aquino EN, Neves AC, Garcia CH, Roepstorff P, Fontes B, et al. Comparison of the neutrophil proteome in trauma patients and normal controls. Protein Pept Lett. 2012;19(6):663–72. doi: 10.2174/092986612800493977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anaya-Prado R, Toledo-Pereyra LH, Lentsch AB, Ward PA. Ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2002;105(2):248–58. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaisdell FW. The pathophysiology of skeletal muscle ischemia and the reperfusion syndrome: a review. Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;10(6):620–30. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(02)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabaroudis A, Gerassimidis T, Karamanos D, Papaziogas B, Antonopoulos V, Sakantamis A. Metabolic alterations of skeletal muscle tissue after prolonged acute ischemia and reperfusion. J Invest Surg. 2003;16(4):219–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yassin MM, Harkin DW, Barros D′Sa AA, Halliday MI, Rowlands BJ. Lower limb ischemia-reperfusion injury triggers a systemic inflammatory response and multiple organ dysfunction. World J Surg. 2002;26(1):115–21. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro MS, Ferreira TC, Cilli EM, Crusca E, Jr, Mendes-Giannini MJ, Sebben A, et al. Hylin a1, the first cytolytic peptide isolated from the arboreal South American frog Hypsiboas albopunctatus (“spotted treefrog”) Peptides. 2009;30(2):291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Souza Castro M, de Sa NM, Gadelha RP, de Sousa MV, Ricart CA, Fontes B, et al. Proteome analysis of resting human neutrophils. Protein and peptide letters. 2006;13(5):481–487. doi: 10.2174/092986606776819529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nascimento A, Chapeaurouge A, Perales J, Sebben A, Sousa MV, Fontes W, et al. Purification, characterization and homology analysis of ocellatin 4, a cytolytic peptide from the skin secretion of the frog Leptodactylus ocellatus. Toxicon. 2007;50(8):1095–104. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrahao MS, Montero EF, Junqueira VB, Giavarotti L, Juliano Y, Fagundes DJ. Biochemical and morphological evaluation of ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat small bowel modulated by ischemic preconditioning. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(4):860–2. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallick IH, Yang W, Winslet MC, Seifalian AM. Ischemia-reperfusion injury of the intestine and protective strategies against injury. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(9):1359–77. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000042232.98927.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris CF, Castro MS, Fontes W. Neutrophil proteome: lessons from different standpoints. Protein Pept Lett. 2008;15(9):995–1001. doi: 10.2174/092986608785849371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74(5):1124–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotter G, Closa D, Prados M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Prats N, Gelpi E, et al. Intestinal preconditioning is mediated by a transient increase in nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222(1):27–32. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamion F, Richard V, Lacoume Y, Thuillez C. Intestinal preconditioning prevents systemic inflammatory response in hemorrhagic shock. Role of HO-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283(2):G408–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00348.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houston JB, Carlile DJ. Incorporation of in vitro drug metabolism data into physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models. Toxicol In Vitro. 1997;11(5):473–8. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(97)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell TW. Hematology of lower vertebrates. In: Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the American College of Veterinary Pathologists (ACVPC) & 39th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Pathology (ASVCP), editor. USA: ACVP and ASVCP; In: In: [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Giulio RT, Hinton DE. Crc Press; 2008. The Toxicology of Fishes; p. 1101. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grootjans J, Lenaerts K, Derikx JP, Matthijsen RA, de Bruine AP, van Bijnen AA, et al. Human intestinal ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammation characterized: experiences from a new translational model. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(5):2283–91. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deitch EA, Landry KN, McDonald JC. Postburn impaired cell-mediated immunity may not be due to lazy lymphocytes but to overwork. Ann Surg. 1985;201(6):793–802. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198506000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Chang KC, Cobb JP, Buchman TG, Korsmeyer SJ, Karl IE. Prevention of lymphocyte cell death in sepsis improves survival in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(25):14541–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erling Junior N, Montero EF, Sannomiya P, Poli-de-Figueiredo LF. Local and remote ischemic preconditioning protect against intestinal ischemic/reperfusion injury after supraceliac aortic clamping. Clinics. 2013;68(12):1548–54. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(12)12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deirmengian GK, Zmistowski B, Jacovides C, O′Neil J, Parvizi J. Leukocytosis is common after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(11):3031–6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1887-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grau AJ, Boddy AW, Dukovic DA, Buggle F, Lichy C, Brandt T, et al. Leukocyte count as an independent predictor of recurrent ischemic events. Stroke. 2004;35(5):1147–52. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000124122.71702.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lantos J, Grama L, Orosz T, Temes G, Roth E. Leukocyte CD11a expression and granulocyte activation during experimental myocardial ischemia and long lasting reperfusion. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2001;6(2):72–6. Summer. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grau AJ, Berger E, Sung KL, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Granulocyte adhesion, deformability, and superoxide formation in acute stroke. Stroke. 1992;23(1):33–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53(1):31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart ML, Ceonzo KA, Shaffer LA, Takahashi K, Rother RP, Reenstra WR, et al. Gastrointestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury is lectin complement pathway dependent without involving C1q. J Immunol. 2005;174(10):6373–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthijsen RA, Huugen D, Hoebers NT, de Vries B, Peutz-Kootstra CJ, Aratani Y, et al. Myeloperoxidase is critically involved in the induction of organ damage after renal ischemia reperfusion. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(6):1743–52. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szokoly M, Nemeth N, Furka I, Miko I. Hematological and hemostaseological alterations after warm and cold limb ischemia-reperfusion in a canine model. Acta Cir Bras. 2009;24(5):338–46. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502009000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson PG, Raiji MT. Evaluation and management of intestinal obstruction. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(2):159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Del Conde I, Cruz MA, Zhang H, Lopez JA, Afshar-Kharghan V. Platelet activation leads to activation and propagation of the complement system. J Exp Med. 2005;201(6):871–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamad OA, Nilsson PH, Wouters D, Lambris JD, Ekdahl KN, Nilsson B. Complement component C3 binds to activated normal platelets without preceding proteolytic activation and promotes binding to complement receptor 1. J Immunol. 2010;184(5):2686–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massberg S, Enders G, Leiderer R, Eisenmenger S, Vestweber D, Krombach F, et al. Platelet-endothelial cell interactions during ischemia/reperfusion: the role of P-selectin. Blood. 1998;92(2):507–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Massberg S, Messmer K. The nature of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Transplant Proc. 1998;30(8):4217–23. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cooper D, Chitman KD, Williams MC, Granger DN. Time-dependent platelet-vessel wall interactions induced by intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284(6):G1027–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00457.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khandoga A, Biberthaler P, Enders G, Axmann S, Hutter J, Messmer K, et al. Platelet adhesion mediated by fibrinogen-intercelllular adhesion molecule-1 binding induces tissue injury in the postischemic liver in vivo. Transplantation. 2002;74(5):681–8. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nocito A, Georgiev P, Dahm F, Jochum W, Bader M, Graf R, et al. Platelets and platelet-derived serotonin promote tissue repair after normothermic hepatic ischemia in mice. Hepatology. 2007;45(2):369–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.21516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lapchak PH, Kannan L, Ioannou A, Rani P, Karian P, Dalle Lucca JJ, et al. Platelets orchestrate remote tissue damage after mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(8):G888–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00499.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu S, Ren J, Han G, Wang G, Gu G, Xia Q, Li J. Mean platelet volume: a controversial marker of disease activity in Crohn's disease. Eur J Med Res. 2012;17:27. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-17-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ntaios G, Gurer O, Faouzi M, Aubert C, Michel P. Mean platelet volume in the early phase of acute ischemic stroke is not associated with severity or functional outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29(5):484–9. doi: 10.1159/000297964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Altintoprak F, Arslan Y, Yalkin O, Uzunoglu Y, Ozkan OV. Mean platelet volume as a potential prognostic marker in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia-retrospective study. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):49. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kozar RA, Holcomb JB, Hassoun HT, Macaitis J, DeSoignie R, Moore FA. Superior mesenteric artery occlusion models shock-induced gut ischemia-reperfusion. J Surg Res. 2004;116(1):145–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradbury AW, Brittenden J, McBride K, Ruckley CV. Mesenteric ischaemia: a multidisciplinary approach. Br J Surg. 1995;82(11):1446–59. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heys SD, Brittenden J, Crofts TJ. Acute mesenteric ischaemia: the continuing difficulty in early diagnosis. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69(807):48–51. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.69.807.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]