Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is common among Hispanic males, but little is known about HPV vaccination in this population. We examined the early adoption of HPV vaccine among a national sample of Hispanic adolescent males.

Methods

We analyzed provider-verified HPV vaccination data from the 2010–2012 National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) for Hispanic males ages 13–17 (n=4,238). Weighted logistic regression identified correlates of HPV vaccine initiation (receipt of one or more doses).

Results

HPV vaccine initiation was 17.1% overall, increasing from 2.8% in 2010 to 31.7% in 2012 (p<0.0001). Initiation was higher among sons whose parents had received a provider recommendation to vaccinate compared to those whose parents had not (53.3% vs. 9.0%; OR=8.77, 95% CI: 6.05–12.70). Initiation was also higher among sons who had visited a healthcare provider in the previous year (OR=2.42, 95% CI: 1.39–4.23). Among parents with unvaccinated sons, Spanish-speaking parents reported much higher intent to vaccinate compared to English-speaking parents (means: 3.52 vs. 2.54, p<0.0001). Spanish-speaking parents were more likely to indicate lack of knowledge (32.9% vs. 19.9%) and not having received a provider recommendation (32.2% vs. 17.7%) as a main reason for not intending to vaccinate (both p<0.05).

Conclusions

HPV vaccination among Hispanic adolescent males has increased substantially in recent years. Ensuring healthcare visits and provider recommendation will be key for continuing this trend. Preferred language may also be important for increasing HPV vaccination and addressing potential barriers to vaccination.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, HPV vaccine, Hispanic, Cancer, NIS-Teen

Introduction

Hispanics are one of the fastest growing populations in the US, currently constituting over 16% of the total population and projected to be 30% by 2050.1,2 The Hispanic population has relatively high rates of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV-related disease (e.g., cervical cancer).3–6 Over 30% of Hispanic adult males have a current HPV infection,3 and they are twice as likely as non-Hispanic white males to be infected with multiple HPV types.4 Hispanic females have the highest cervical cancer incidence rate of any racial/ethnic group in the US.6 HPV is highly transmissible between sexual partners,7 so Hispanic males likely play an important role in cervical cancer incidence among Hispanic females.

US guidelines have recommended HPV vaccine for males since October 2009.8 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) first provided a permissive recommendation that allowed the three-dose vaccine series to be administered to males ages 9–26.8 In October 2011, the ACIP began recommending routine HPV vaccination for males ages 11–12 with catch-up vaccination for ages 13–21 and up to age 26 for high-risk males.9 Parents’ acceptance of HPV vaccine for their adolescent sons tends to be high,10–12 but current vaccine coverage among US adolescent males is low. Recent data indicate that 21% or less of adolescent males have received any doses of HPV vaccine and less than 10% have received all three doses.13–15 Although a Healthy People 2020 objective has not yet been set for males, current HPV vaccine coverage among males falls far short of the goal of 80% coverage with three doses established for females.16

Few studies have focused on HPV vaccination among Hispanic males. Most Hispanic parents are willing to vaccinate their sons (range 59%–92%),17–19 and research suggests that HPV vaccine initiation may be slightly higher among Hispanic adolescent males compared to non-Hispanic whites.13,15 However, no studies we are aware of have identified correlates of HPV vaccination among Hispanic males or reasons why parents are not vaccinating their Hispanic sons. We believe such information is important given the HPV-related disparities that exist among Hispanics and because Hispanics may face unique challenges to receiving HPV vaccine (e.g., acculturation). We analyzed data among a national sample of Hispanic adolescent males to examine HPV vaccine coverage in the first few years following vaccine availability for males in the US. Results will be useful for designing effective HPV vaccination programs for this population.

Material and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a secondary analysis of publicly available data from the 2010–2012 National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen).20–22 The methodology of the NIS-Teen has been described in great detail23 and briefly here. The NIS-Teen is an annual survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to monitor vaccination among 13–17 year-olds in the US. Data collection occurs in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the US Virgin Islands.

The CDC uses a complex stratified sampling strategy to obtain a national probability sample of adolescents ages 13–17 for the NIS-Teen. For 2010, the survey used a random-digit-dialed (RDD) sampling frame that consisted of landline telephones, whereas 2011 and 2012 used a dual-frame sampling approach with independent RDD samples of landline and cellular telephone sampling frames.20–22 For households containing more than one adolescent ages 13–17, one is randomly chosen as the index adolescent. Data collection for the NIS-Teen consists of two phases: 1) a telephone survey with parents of the adolescents; and 2) a mailed survey to adolescents’ healthcare providers. Data obtained from provider records are the basis for the NIS-Teen vaccination estimates.13,24,25

Excluding participants from the US Virgin Islands, datasets included 19,257 adolescents from 2010 (household response rate=58.0%24), 23,564 adolescents from 2011 (household response rate=57.2% for landline households and 22.4% for cellular households25), and 19,199 adolescents from 2012 (household response rate=55.1% for landline households and 23.6% for cellular households13). These datasets represent all years with HPV vaccination data available for males at the time of analyses. We report data on 4,238 Hispanic adolescent males from these datasets (all participants included had provider-verified HPV vaccination data). The NIS-Teen established Hispanic ethnicity by asking parents whether adolescents were Hispanic or Latino.

The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approved NIS-Teen data collection, and the NIS-Teen obtained informed consent from all participants. Analysis of deidentified data from the survey is exempt from the federal regulations for the protection of human research participants. The Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University determined this study was exempt from review.

Measures

Outcome Variables

We examined HPV vaccine initiation (receipt of at least one dose of HPV vaccine) as the primary outcome variable since few males in the US have received any doses of HPV vaccine.13 For descriptive purposes, we also examined HPV vaccine completion (receipt of all three doses).

We examined parents’ intent to get their sons HPV vaccine in the next year among parents whose sons had not received any doses of HPV vaccine (i.e., unvaccinated). The NIS-Teen assessed intent by asking these parents, “How likely is it that [TEEN] will receive HPV shots in the next 12 months?” Response options included “not likely at all,” “not too likely,” “not sure/don’t know,” “somewhat likely,” and “very likely” (coded 1–5). Parents who gave one of the first three responses then indicated the main reason why their sons would not receive HPV vaccine in the next year. Parents could indicate multiple reasons for this open-ended item. The CDC coded responses and then created a dichotomous variable for each main reason for use in analyses (1=reason reported, 0=reason not reported).

Potential Correlates

The NIS-Teen assessed various characteristics of sons, parents, and households (Table 1). Son characteristics included age, race (since Hispanic is an ethnicity and not a race), if they visited a healthcare provider in the previous year, healthcare coverage, and if they currently lived in the state where they were born (i.e., geographic mobility). We examined geographic mobility because relocation may disrupt continuity of care. Parent characteristics included mother’s age, education level, and marital status. If someone other than the mother completed the parent survey, this individual provided information about the mother. Parents indicated if they had ever received a healthcare provider recommendation to get their sons HPV vaccine. We examined whether parents completed the NIS-Teen telephone survey in English or Spanish (i.e., preferred language) as a proxy measure of acculturation. We acknowledge that acculturation is a complex construct, but language preference is a commonly used proxy for acculturation that correlates with acculturation scales or is a domain within several such scales.26

Table 1.

Characteristics of parents and their Hispanic adolescent sons from the NIS-Teen, 2010–2012 (n=4,238)

| n (weighted %) | |

|---|---|

| Year | |

| 2010 | 1270 (32.2) |

| 2011 | 1647 (31.8) |

| 2012 | 1321 (36.1) |

| Son characteristics | |

| Age | |

| 13 yr | 892 (20.4) |

| 14 yr | 927 (20.3) |

| 15 yr | 880 (21.7) |

| 16 yr | 804 (19.1) |

| 17 yr | 735 (18.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 3609 (86.1) |

| Black | 246 (5.6) |

| Other | 383 (8.3) |

| Currently lives in state where born | |

| No | 1257 (29.9) |

| Yes | 2981 (70.1) |

| Visited healthcare provider in previous year | |

| No | 890 (24.8) |

| Yes | 3300 (75.2) |

| Healthcare coverage | |

| Private insurance | 1827 (35.5) |

| Public insurance | 1838 (50.3) |

| No insurance | 539 (14.1) |

| Parent characteristics | |

| Mother's age | |

| <35 yr | 512 (14.0) |

| 35–44 yr | 2156 (55.8) |

| 45+ yr | 1570 (30.2) |

| Mother's education | |

| Less than high school | 1313 (37.2) |

| High school | 1003 (25.7) |

| Some college | 963 (18.7) |

| College graduate | 959 (18.4) |

| Mother's marital status | |

| Not married | 1302 (33.1) |

| Married | 2936 (66.9) |

| Language of NIS-Teen interview | |

| English | 2540 (52.5) |

| Spanish | 1690 (47.5) |

| Received provider recommendation to get son HPV vaccine | |

| No | 3209 (81.8) |

| Yes | 804 (18.2) |

| Household characteristics | |

| Poverty status | |

| Below poverty | 1519 (44.6) |

| Above poverty, ≤$75,000 | 1613 (39.2) |

| Above poverty, >$75,000 | 915 (16.1) |

| Number of children in household | |

| 1 | 1281 (23.2) |

| 2–3 | 2392 (59.7) |

| 4+ | 565 (17.1) |

| Region of residence | |

| Northeast | 616 (12.4) |

| Midwest | 521 (9.3) |

| South | 1755 (34.3) |

| West | 1346 (43.9) |

Note. Totals may not sum to stated sample size due to missing data. Percents may not sum to 100% due to rounding. Frequencies were not weighted. NIS-Teen = National Immunization Survey-Teen; HPV = human papillomavirus.

Household characteristics included poverty status (based on US Census poverty thresholds20–22), number of children less than 18 years of age in the household, and region of residence in the US (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West). Unlike previous analyses of NIS-Teen data,15,27 we were not able to examine parents’ awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine and adolescents’ eligibility for the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program since these variables were not included in the 2012 public-use NIS-Teen dataset.22 The VFC program is a federal program that provides vaccines free of charge to children who might not otherwise be vaccinated because of inability to pay (uninsured, underinsured, etc.).28

Data Analysis

We examined descriptive statistics for all outcome variables. We used binary logistic regression to identify correlates of HPV vaccine initiation (our primary outcome). We entered variables with p<0.10 in bivariate analyses into a multivariate model, which produced adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Lastly, we determined if parents’ intent to vaccinate (linear and binary logistic regression) and reasons for not intending to vaccinate (binary logistic regression) differed by parents’ preferred language, as these outcomes differed by preferred language in our prior research on Hispanic females.29

We combined multiple years of NIS-Teen data for analyses using recommended methods and applied appropriate sampling weights in determining proportions and effect estimates.20–22 We used procedures for analyzing complex survey data in SAS Version 9.2 (Cary, NC). Statistical tests were two-tailed with a critical alpha of 0.05.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Most sons were ages 13–15 (62.4%), white (86.1%), lived in the state where they were born (70.1%), and had visited a healthcare provider in the previous year (75.2%) (Table 1). Most mothers were at least 35 years old (86.0%) and did not have a college degree (81.6%). Almost half (47.5%) of parents completed the NIS-Teen telephone survey in Spanish. Only 18.2% of parents had received a recommendation from a healthcare provider to get their sons HPV vaccine, though receipt of a recommendation increased each year (2010=4.3%, 2011=14.1%, 2012=24.3%; p<0.0001).

HPV Vaccine Uptake

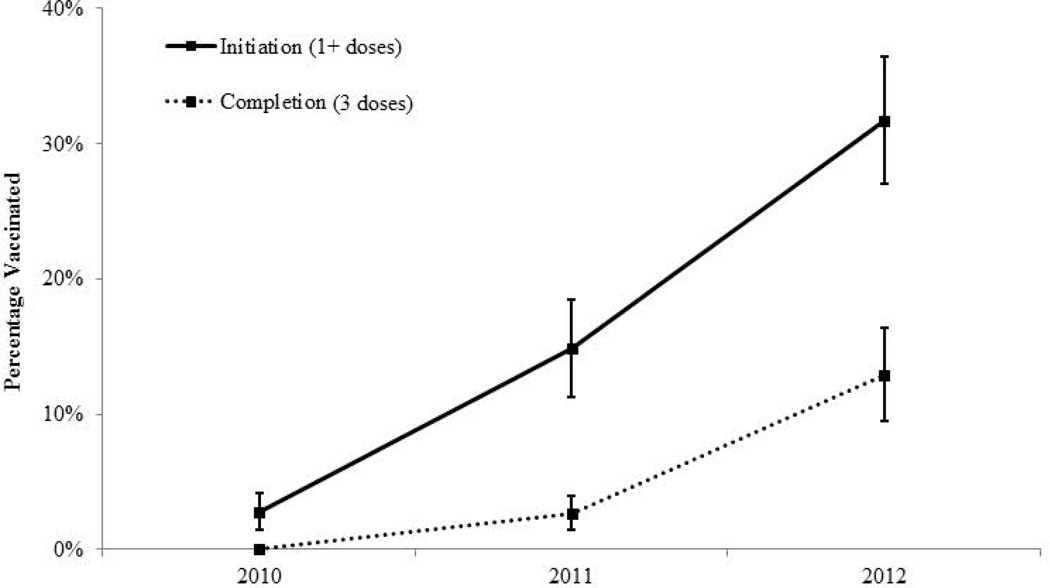

Overall, 17.1% of Hispanic adolescent males had received at least one dose of HPV vaccine. Initiation increased each year, with 2.8% initiation in 2010, 14.9% initiation in 2011, and 31.7% initiation in 2012 (Figure 1). Although only 5.5% of Hispanic adolescent males overall had completed the three-dose HPV vaccine series, completion increased each year (2010: <0.1%; 2011: 2.7%; 2012: 12.9%). The yearly increases in both initiation and completion were statistically significant (all p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

HPV vaccine coverage among Hispanic adolescent males in the United States, 2010–2012. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals

Correlates of HPV Vaccine Initiation

In multivariate analyses (Table 2), initiation was higher in 2011 (OR=4.22, 95% CI: 2.25–7.92) and 2012 (OR=10.61, 95% CI: 5.78–19.47) compared to 2010. Initiation was higher among sons whose parents had received a provider recommendation to vaccinate compared to those whose parents had not (53.3% vs. 9.0%; OR=8.77, 95% CI: 6.05–12.70). Initiation was also higher among sons who had visited a healthcare provider in the previous year (OR=2.42, 95% CI: 1.39–4.23). Initiation was lower among sons from households that were above poverty and had an income greater than $75,000 compared to sons from households that were below poverty (OR=0.47, 95% CI: 0.23–0.95).

Table 2.

Correlates of HPV vaccine initiation (receipt of at least one dose of HPV vaccine) among Hispanic adolescent males, 2010–2012 (n=4,238)

| No. Initiated / Total No. in Category (weighted %) |

Bivariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 705/4238 (17.1) | -- | -- |

| Year | |||

| 2010 | 53/1270 (2.8) | ref. | ref. |

| 2011 | 274/1647 (14.9) | 6.14 (3.44–10.95)** | 4.22 (2.25–7.92)** |

| 2012 | 378/1321 (31.7) | 16.30 (9.41–28.24)** | 10.61 (5.78–19.47)** |

| Son characteristics | |||

| Age | |||

| 13 yr | 151/892 (15.0) | ref. | -- |

| 14 yr | 155/927 (19.1) | 1.34 (0.84–2.16) | -- |

| 15 yr | 147/880 (16.7) | 1.14 (0.72–1.79) | -- |

| 16 yr | 132/804 (18.5) | 1.29 (0.78–2.14) | -- |

| 17 yr | 120/735 (16.1) | 1.09 (0.65–1.82) | -- |

| Race | |||

| White | 585/3609 (17.2) | ref. | ref. |

| Black | 47/246 (22.1) | 1.37 (0.75–2.49) | 1.54 (0.75–3.15) |

| Other | 73/383 (12.5) | 0.69 (0.44–1.09)† | 0.65 (0.37–1.13)† |

| Currently lives in state where born | |||

| No | 227/1257 (20.0) | ref. | ref. |

| Yes | 478/2981 (15.8) | 0.75 (0.53–1.06)† | 0.74 (0.50–1.10) |

| Visited healthcare provider in previous year | |||

| No | 97/890 (10.8) | ref. | ref. |

| Yes | 597/3300 (19.1) | 1.96 (1.27–3.03)* | 2.42 (1.39–4.23)* |

| Healthcare coverage | |||

| Private insurance | 212/1827 (11.3) | ref. | ref. |

| Public insurance | 416/1838 (21.7) | 2.18 (1.53–3.11)** | 1.46 (0.89–2.40) |

| No insurance | 72/539 (14.4) | 1.32 (0.77–2.26) | 1.40 (0.58–3.39) |

| Parent characteristics | |||

| Mother's age | |||

| <35 yr | 100/512 (19.9) | ref. | -- |

| 35–44 yr | 378/2156 (17.8) | 0.87 (0.56–1.34) | -- |

| 45+ yr | 227/1570 (14.4) | 0.68 (0.43–1.08) | -- |

| Mother's education | |||

| Less than high school | 282/1313 (22.1) | ref. | ref. |

| High school | 173/1003 (16.0) | 0.67 (0.45–1.00)* | 0.62 (0.37–1.04)† |

| Some college | 118/963 (13.0) | 0.53 (0.34–0.82)* | 0.77 (0.39–1.55) |

| College graduate | 132/959 (12.6) | 0.51 (0.33–0.79)* | 0.92 (0.45–1.89) |

| Mother's marital status | |||

| Not married | 242/1302 (18.2) | ref. | -- |

| Married | 463/2936 (16.5) | 0.89 (0.64–1.23) | -- |

| Language of NIS-Teen interview | |||

| English | 331/2540 (11.8) | ref. | ref. |

| Spanish | 370/1690 (22.8) | 2.20 (1.61–3.00)** | 1.59 (0.96–2.65)† |

| Received provider recommendation to get son HPV vaccine | |||

| No | 251/3209 (9.0) | ref. | ref. |

| Yes | 407/804 (53.3) | 11.52 (8.07–16.46)** | 8.77 (6.05–12.70)** |

| Household characteristics | |||

| Poverty status | |||

| Below poverty | 348/1519 (23.2) | ref. | ref. |

| Above poverty, ≤$75,000 | 230/1613 (13.6) | 0.52 (0.37–0.74)* | 0.71 (0.45–1.11) |

| Above poverty, >$75,000 | 100/915 (8.9) | 0.32 (0.20–0.51)** | 0.47 (0.23–0.95)* |

| Number of children in household | |||

| 1 | 174/1281 (13.0) | ref. | ref. |

| 2–3 | 415/2392 (18.1) | 1.47 (1.01–2.15)* | 1.41 (0.92–2.17) |

| 4+ | 116/565 (19.1) | 1.58 (0.94–2.66) | 1.26 (0.69–2.30) |

| Region of residence | |||

| Northeast | 116/616 (15.9) | ref. | -- |

| Midwest | 90/521 (18.9) | 1.23 (0.78–1.93) | -- |

| South | 303/1755 (16.5) | 1.05 (0.72–1.53) | -- |

| West | 196/1346 (17.4) | 1.11 (0.74–1.68) | -- |

Note. Totals may not sum to stated sample size due to missing data. Frequencies were not weighted. Multivariate model did not include variables with dashes (--). Multivariate model included data on 3782 Hispanic adolescent males due to missing data for potential correlates. HPV = human papillomavirus; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; ref. = referent group; NIS-Teen = National Immunization Survey-Teen.

p<0.10,

p<0.05,

p<0.0001

Intent to Vaccinate and Reasons for Not Intending to Vaccinate

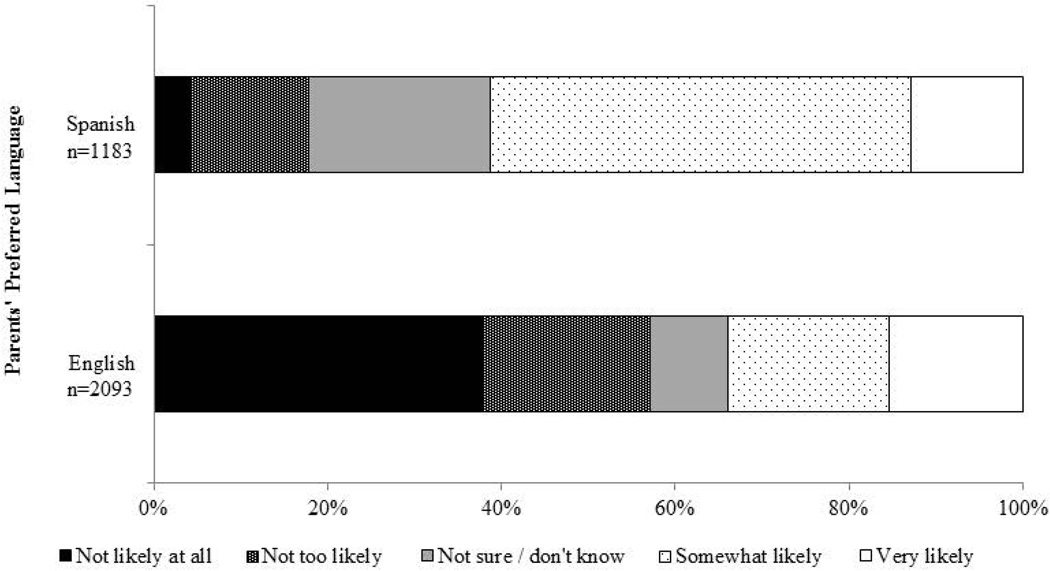

Parents with unvaccinated sons reported moderate intent to vaccinate in the next year (mean=2.96, standard error [SE]=0.04). About 45.7% of these parents indicated their sons were “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to receive HPV vaccine in the next year, 14.2% were not sure, and 40.2% indicated vaccination was “not too likely” or “not likely at all.” Parents whose preferred language was Spanish reported much higher intent to vaccinate (mean=3.52, SE=0.05) compared to parents whose preferred language was English (mean=2.54, SE=0.06)(p<0.0001; Figure 2). About 61.2% of Spanish-speaking parents indicated their sons were “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to receive HPV vaccine in the next year, compared to only 33.9% of English-speaking parents (p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Parents’ intent to get their Hispanic adolescent sons HPV vaccine in the next year, 2010–2012

The most common main reasons for parents not intending to vaccinate their sons in the next year were lack of knowledge (23.6%), believing vaccination is not needed or not necessary (22.5%), and not having received a provider recommendation (22.0%) (Table 3). Compared to English-speaking parents, Spanish-speaking parents were more likely to indicate lack of knowledge (32.9% vs. 19.9%) and not having received a provider recommendation (32.2% vs. 17.7%) as a main reason (both p<0.05). Conversely, English-speaking parents were more likely to indicate believing vaccination is not needed or not necessary (27.2% vs. 10.6%), son not sexually active (11.2% vs. 3.5%), their child is male (7.5% vs. 2.2%), and concerns about vaccine safety and side effects (6.8% vs. 3.1%) as a main reason (all p<0.05).

Table 3.

Main reasons why parents did not intend to get their Hispanic adolescent sons HPV vaccine in the next year, 2010–2012 (n=1751)

| Parents’ Preferred Language | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n (weighted %) |

English n (weighted %) |

Spanish n (weighted %) |

p | |

| Lack of knowledge | 358 (23.6) | 247 (19.9) | 111 (32.9) | 0.0030 |

| Vaccination not needed or not necessary | 392 (22.5) | 329 (27.2) | 61 (10.6) | <0.0001 |

| Did not receive provider recommendation | 408 (22.0) | 294 (17.7) | 114 (32.2) | 0.0004 |

| Son not sexually active | 185 (9.0) | 160 (11.2) | 25 (3.5) | 0.0002 |

| Child is male | 138 (6.0) | 123 (7.5) | 14 (2.2) | 0.0016 |

| Vaccine safety concern/side effects | 104 (5.8) | 89 (6.8) | 15 (3.1) | 0.0405 |

| Costs | 40 (3.8) | 20 (3.0) | 20 (5.9) | 0.2470 |

| Son not appropriate age | 70 (3.5) | 53 (3.4) | 17 (3.9) | 0.7606 |

| Not a school requirement | 34 (2.6) | 22 (2.6) | 12 (2.5) | 0.9215 |

Note. Table includes parents of unvaccinated sons who indicated they were “not likely at all,” “not too likely,” or “not sure/don’t know” about getting their sons HPV vaccine in the next year. Table does not include reasons that were reported by less than 2.0% of parents. Frequencies were not weighted. Reported p-values are from binary logistic regression models that determined if each reason differed by parents’ preferred language.

Discussion

Our study examined the early adoption of HPV vaccine among a national sample of Hispanic adolescent males. According to NIS-Teen data, just under 20% of Hispanic adolescent males had initiated the HPV vaccine series and only about 5% had received all three doses. Despite this modest coverage overall, both initiation and completion increased substantially over the years examined (over 30% initiation and 12% completion in 2012). These increases were likely due in part to the different ACIP recommendations that were in place during these years. The ACIP initially provided a permissive recommendation for HPV vaccine for males in October 2009,8 which was replaced by a stronger recommendation for routine administration in October 2011.9 The updated recommendation may have helped increase HPV vaccination by increasing provider recommendation for vaccination (which increased each year in our study) and insurance coverage of HPV vaccine for males. The VFC program and some private health insurance plans covered HPV vaccine for males under the permission recommendation,30 but coverage by private health insurance plans has increased in recent years due to the updated recommendation and the Affordable Care Act.31,32

Despite the observed annual increases, interventions will likely be needed to maximize HPV vaccine coverage. Similar increases in HPV vaccination occurred among adolescent females in the first few years following vaccine availability, but increases have stalled in recent years.33,34 Our study highlights potential leverage points and strategies for future interventions. The most promising strategy will be to ensure healthcare visits among Hispanic adolescent males and increase healthcare provider’s recommendation for vaccination during visits. Both of these factors were correlated with HPV vaccine initiation in multivariate analyses, with provider recommendation being the strongest determinant (which is similar to previous studies14,15). However, a majority of parents in our study reported not having received a healthcare provider’s recommendation to vaccinate, suggesting that many missed opportunities for recommending and administering HPV vaccine are occurring during existing healthcare visits. As suggested by the President’s Cancer Panel, reducing these missed opportunities will be critical for increasing HPV vaccine coverage.35

Parents’ preferred language, our proxy measure of acculturation, was correlated with several outcomes examined. Spanish-speaking parents reported higher levels of intent to vaccinate their sons in the next year and different main reasons for not intending to vaccinate. These findings are similar to those of our prior analyses of Hispanic adolescent females.29 Lack of knowledge and lack of a provider recommendation were the most common main reasons for not intending to vaccinate among Spanish-speaking parents, while believing vaccination is not needed was the most common main reason among parents whose preferred language was English. Our findings suggest that future HPV vaccine interventions for Hispanic males should be prepared to address different potential barriers to vaccination based on preferred language.

Results also suggested that HPV vaccine initiation was more common among sons whose parents whose preferred language was Spanish (p<0.10 in multivariate analyses). This is somewhat surprising since past studies examining HPV vaccination among Hispanics found lower HPV vaccine coverage among Hispanics with less US acculturation.36,37 Our finding may be attributable to several factors, including differences between English- and Spanish-speaking individuals in terms of healthcare utilization, attitudes and beliefs about HPV vaccine, and VFC eligibility. Although we were not able to examine VFC eligibility, Spanish-speaking parents were more likely to be from households that were below poverty (which was correlated with HPV vaccine initiation in multivariate analyses) and to have sons without health insurance (both p<0.05). Both factors may have made sons of Spanish-speaking parents eligible for the VFC program. Future research using more sophisticated measures of acculturation is needed to further understand how acculturation (and which domains of acculturation) may affect HPV vaccination outcomes.

Our study had several important strengths, including a large sample of Hispanic adolescent males from throughout the US, HPV vaccination data based on healthcare provider records, and examining variables that may be especially relevant to the Hispanic population (e.g., parents’ preferred language [a proxy for acculturation]). The correlations observed in our study need to be verified in longitudinal studies, particularly to establish the temporal relationships between vaccination and correlates that can change over time (e.g., poverty status).38 The NIS-Teen public-use datasets did not contain information regarding country of origin among Hispanics (e.g., Mexican, Cuban, etc.) or VFC eligibility (not available for 201222). We believe it is important for these data to be available in future public-use NIS-Teen datasets to allow for their inclusion in analyses.

Current HPV vaccine coverage among Hispanic adolescent males is modest but has increased substantially in recent years. Ensuring healthcare visits and increasing provider recommendation for vaccination at such visits will be important for continuing this increasing trend. Preferred language may also be important for increasing HPV vaccination, and future programs targeting this population need to consider how potential barriers to vaccination may differ by acculturation.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was funded by Cervical Cancer-Free America, via an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. Additional support was provided by the National Cancer Institute (P30CA016058 and R25CA57726).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: PLR, NTB, EDP, and JSS have received research grants from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. NTB has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, served on paid advisory boards, and served as a paid speaker for Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. JSS has received unrestricted educational grants, served on paid advisory boards, and served as a paid speaker for GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- 1.Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population: 2010. 2010 Census briefs. 2011 Available from URL: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. population projections. 2008 Available from URL: http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/index.html.

- 3.Nyitray A, Nielson CM, Harris RB, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for anal human papillomavirus infection in heterosexual men. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(12):1676–1684. doi: 10.1086/588145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielson CM, Harris RB, Flores R, et al. Multiple-type human papillomavirus infection in male anogenital sites: Prevalence and associated factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(4):1077–1083. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hariri S, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among females in the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2006. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(4):566–573. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson M, Saraiya M, Benard V, et al. Burden of cervical cancer in the United States, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2855–2864. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiter PL, Pendergraft WF, 3rd, Brewer NT. Meta-analysis of human papillomavirus infection concordance. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(11):2916–2931. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4, Gardasil) for use in males and guidance from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(20):630–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males--Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(50):1705–1708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liddon N, Hood J, Wynn BA, Markowitz LE. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine for males: A review of the literature. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(2):113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiter PL, McRee AL, Kadis JA, Brewer NT. HPV vaccine and adolescent males. Vaccine. 2011;29(34):5595–5602. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiter PL, McRee AL, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. HPV vaccine for adolescent males: Acceptability to parents post-vaccine licensure. Vaccine. 2010;28(38):6292–6297. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(34):685–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiter PL, McRee AL, Pepper JK, Gilkey MB, Galbraith KV, Brewer NT. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among a national sample of adolescent males. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1419–1427. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiter PL, Gilkey MB, Brewer NT. HPV vaccination among adolescent males: Results from the national immunization survey-teen. Vaccine. 2013;31(26):2816–2821. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. 2011 Available from URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.

- 17.Watts LA, Joseph N, Wallace M, et al. HPV vaccine: A comparison of attitudes and behavioral perspectives between Latino and non-Latino women. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podolsky R, Cremer M, Atrio J, Hochman T, Arslan AA. HPV vaccine acceptability by Latino parents: A comparison of U.S. and Salvadoran populations. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornfeld J, Byrne MM, Vanderpool R, Shin S, Kobetz E. HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability among Hispanic fathers. J Prim Prev. 2013;34(1–2):59–69. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0297-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. The 2010 National Immunization Survey - Teen. [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). National Center for Health Statistics. The 2011 National Immunization Survey - Teen. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. The 2012 National Immunization Survey - Teen. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain N, Singleton JA, Montgomery M, Skalland B. Determining accurate vaccination coverage rates for adolescents: The National Immunization Survey-Teen 2006. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(5):642–651. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13 through 17 years --- United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1117–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:671–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: A systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(7):983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reiter PL, Katz ML, Paskett ED. HPV vaccination among adolescent females from Appalachia: Implications for cervical cancer disparities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(12):2220–2230. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for children program (VFC) 2013 Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html.

- 29.Reiter PL, Gupta K, Brewer NT, et al. Provider-verified HPV vaccine coverage among a national sample of Hispanic adolescent females. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(5):742–754. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haupt RM, Sylvester GC. HPV disease in males and vaccination: Implications and opportunities for pediatricians. Infectious Diseases in Children. 2010 Available from URL: http://www.pediatricsupersite.com/view.aspx?rid=66396. [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Affordable Care Act and immunization. 2012 Available from URL: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/factsheets/2010/09/The-Affordable-Care-Act-and-Immunization.html.

- 32.Trinidad J. Promoting human papilloma virus vaccine to prevent genital warts and cancers. 2012 Available from URL: http://www.fenwayhealth.org/site/DocServer/PolicyFocus_HPV_v4_10.09.12.pdf?docID=9961. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007–2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2013 - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(29):591–595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moss JL, Gilkey MB, Reiter PL, Brewer NT. Trends in HPV vaccine initiation among adolescent females in North Carolina, 2008–2010. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(11):1913–1922. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.A report to the President of the United States from the President's Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2014. The President's Cancer Panel. Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: Urgency for action to prevent cancer. Available from URL: http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/HPV/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerend MA, Zapata C, Reyes E. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among daughters of low-income Latina mothers: The role of acculturation. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(5):623–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chando S, Tiro JA, Harris TR, Kobrin S, Breen N. Effects of socioeconomic status and health care access on low levels of human papillomavirus vaccination among Spanish-speaking Hispanics in California. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):270–272. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: An introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]