Abstract

Ancestor–descendant relationships (ADRs), involving descent with modification, are the fundamental concept in evolution, but are usually difficult to recognize. We examined the cladistic relationship between the only reported fossil pygmy right whale, †Miocaperea pulchra, and its sole living relative, the enigmatic pygmy right whale Caperea marginata, the latter represented by both adult and juvenile specimens. †Miocaperea is phylogenetically bracketed between juvenile and adult Caperea marginata in morphologically based analyses, thus suggesting a possible ADR—the first so far identified within baleen whales (Cetacea: Mysticeti). The †Miocaperea–Caperea lineage may show long-term morphological stasis and, in turn, punctuated equilibrium.

Keywords: phylogenetic methods, Cetacea, Mysticeti, ontogenetic clade, punctuated equilibrium

1. Introduction

Descent with modification has been the essence of evolution since 1859 [1]. Ideally, an understanding of evolution would be based on ancestor–descendant relationships (ADRs). In reality, ADRs have usually been shown only for groups with abundant fossils in a dense stratigraphic record, including vertebrates [2], macro-invertebrates [3] and especially microfossils [4]. Since the development of cladistics [5] in the 1960s, emphasis has shifted from ADRs to phylogenetic sister-group relationships (SGRs). Indeed, fossils and ADRs have been discussed rather cursorily in the literature [6] as the debates of ancestry and cladistics in the 1970s and 1980s (e.g. pros: [7,8]; cons: [9,10]).

It is problematic to establish ADRs in vertebrate evolution, even with abundant fossils (e.g. [2]). Consider the filter-feeding baleen whales, the largest vertebrates [11], which clearly evolved from toothed stem Mysticeti [12–16]. The evolution of filter-feeding and large size involved dramatic structural and functional shifts in evolution. Species in the †Aetiocetidae were proposed to have teeth and baleen [12], potentially bridging the morphological gap between toothed Mysticeti and baleen-bearing Mysticeti. However, there is no close ADR between known toothed Mysticeti [12,13] and baleen-bearing Mysticeti [17,18]. Likewise, the oldest fossil mysticete, †Llanocetus denticrenatus [19] (late Eocene, Antarctica), is not clearly a direct descendant from known Archaeoceti and/or directly ancestral to any named mysticete. To establish ADRs, we must understand ancestral morphology either through fossils or through the proxy of juvenile morphology [20,21]. Here, we coded the morphology of an individual juvenile Caperea for use as a discrete operational taxonomic unit (OTU) in phylogenetic analyses. The adult and juvenile Caperea bracket the fossil †Miocaperea pulchra, producing a pattern that is consistent with ADRs, and that has implications for recognizing punctuated equilibrium in mysticete evolution.

2. Material and methods

We used matrices from articles on: (i) a new Caperea-like fossil, †Miocaperea pulchra (late Miocene, 7–8 Ma) [22], and (ii) a new phylogenetic interpretation of Caperea marginata [23]. We retained the original codings to optimize comparison with published results. The two matrices [22,23] cover diverse fossil and modern mysticetes, and produce different phylogenies: Bisconti [22] placed C. marginata close to right whales, Balaenidae, whereas Fordyce & Marx [23] placed C. marginata as an extant relict species in the family Cetotheriidae.

Initially, we examined 35 variably complete juvenile skeletons of Caperea marginata (electronic supplementary material, table S1). We considered that individual juveniles of slightly different ages/sizes could be merged into composite OTUs, or coded as separate OTUs, but we saw no clear objective way to discriminate age classes among the 35 juveniles and so chose one well-preserved specimen as a representative juvenile OTU. Specimen SAM M9079 (condylobasal length = 50.3 cm) was coded (photos of SAM M9079: supplementary files in [21]) and added to the original Bisconti matrix [22], which already contained adult C. marginata and †M. pulchra. Codings for †M. pulchra and the juvenile C. marginata were added to the Fordyce & Marx matrix [23], which already contained adult C. marginata. Details of TNT (v. 1.1) [24] settings and morphological scorings for phylogenetic analyses are in the electronic supplementary material and two separate TNT files.1

3. Results

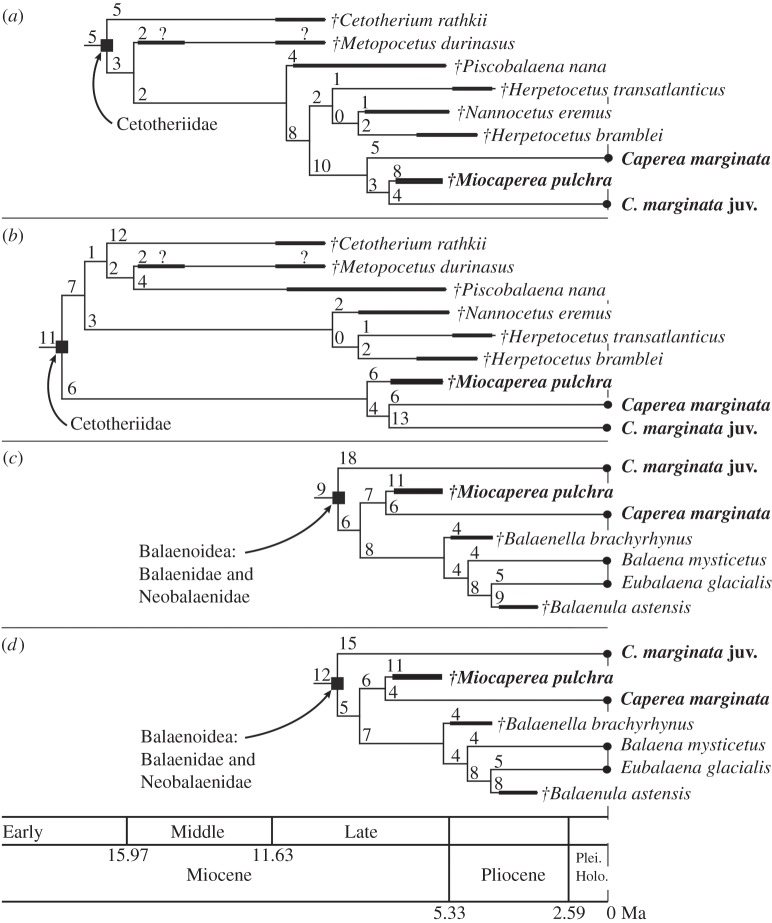

†Miocaperea pulchra consistently plots close to adult and/or juvenile Caperea marginata (figure 1, time-calibrated phylogenies). The Fordyce & Marx matrix [23] analysed with equal weights (figure 1a) shows †M. pulchra as the sister group to the juvenile C. marginata. With implied weights (figure 1b), †M. pulchra is basal to adult and juvenile C. marginata.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic placement of †Miocaperea pulchra in relation to adult and juvenile Caperea marginata with stratigraphically calibrated trees. (a) Extracted phylogeny of Cetotheriidae, using data matrix of [23] with equally weighted setting. (b) Same as (a), but with implied weighting (k = 3). (c) Extracted phylogeny of Balaenoidea, using data matrix of [22] with equally weighted setting. (d) Same as (c), but with implied weighting (k = 3). For details of full phylogenies from each result, see electronic supplementary material. The number above each branch indicates how many characters change between the taxon and node. Dagger (†) indicates extinct species. juv, juvenile; Plei, Pleistocene; Holo, Holocene.

In the Bisconti matrix [22], †M. pulchra forms the sister taxon to adult C. marginata (figure 1c—equal weights; 1d—implied weights), while juvenile C. marginata represents the adjacent and most basal lineage in the Balaenoidea. Different synapomorphies drive the phylogenies from the two published matrices [22,23], placing †M. pulchra either basal to a clade comprising adult + juvenile C. marginata, or as the sister taxon to either the juvenile or the adult. Details of synapomorphies for each clade from two different matrices are in the electronic supplementary material.

4. Discussion

The ADR can be considered cladistically by using adult and juvenile specimens of a single species as separate OTUs, in expectation that the OTUs might then delimit what we term an ontogenetic clade. An ontogenetic clade would arise if the adult OTU plotted more crownward, and the conspecific juvenile plotted more basally. The phylogenetic position of a fossil, either within or outside the ontogenetic clade, provides a way to consider the ADR in evolution. In this case, one or other of the juvenile and adult Caperea marginata plot in a clade with †Miocaperea pulchra, or lie immediately adjacent. This ‘bracketing’ leads us to consider that †M. pulchra is ancestral to C. marginata. There are four possible evolutionary relationships for †Miocaperea and Caperea (figure 2):

(1) the most recent common ancestor of †Miocaperea + Caperea is unknown (figure 2a) (SGR),

(2) †Miocaperea is the ancestor of Caperea (figure 2b,c), with †Miocaperea–Caperea representing an anagenetic lineage (figure 2b) (ADR),

(3) as for (2) but with Caperea split (by cladogenesis) from †Miocaperea (figure 2c) (ADR),

(4) †Miocaperea split from a long Caperea lineage, subsequently going extinct (figure 2d), making Caperea ancestral to †Miocaperea (ADR).

Figure 2.

Four possible evolutionary scenarios of †Miocaperea–Caperea relationships with a stratigraphically calibrated diagram. (a) An unknown common ancestor that remains undetected. (b) †Miocaperea–Caperea forms an anagenetic lineage. (c) Caperea split from †Miocaperea. (d) †Miocaperea split from Caperea. Black square denotes the ancestor of living Caperea. Plei, Pleistocene; Holo, Holocene.

Especially for fossil vertebrates, there is a low probability of recovering ancestors from the fossil record, and thus a low likelihood of recognizing ADRs [25]. The improbability of finding ancestors would allow scenario 1 (figure 2a) to represent †Miocaperea–Caperea evolution. Results do not preclude a SGR for †Miocaperea–Caperea, with an unknown ancestor at the branching node, rather than the ADR of scenario 1.

Consider two aspects of ADRs for †Miocaperea–Caperea. First, when †Miocaperea is bracketed cladistically between juvenile and adult Caperea, †Miocaperea could be ancestral to Caperea, not merely in a SGR. Whether anagenesis (figure 2b) or cladogenesis (2c) is involved remains uncertain. Scenario 4, with C. marginata ancestral to †M. pulchra (figure 2d), is unlikely, since adult C. marginata is derived relative to †M. pulchra in some features (e.g. anterior elongation of the pars cochlearis, and other character states in electronic supplementary material).

Second, C. marginata shows paedomorphic neoteny, which reduces the rate of morphological development during early ontogeny [26]. Given the link between ontogeny and phylogeny [20], paedomorphic neoteny could scale into long-term (7–8 Ma) morphological stasis in the †Miocaperea–Caperea lineage. Stasis is, in turn, a key aspect of punctuated equilibrium [27,28]. Our results, and the minor morphological differences noted by Bisconti between †Miocaperea and Caperea, are consistent with minimal long-term morphological change in the lineage, allowing punctuated equilibrium—geologically rapid origination followed by a long interval of relative stasis [27,28].

The enigmatic Caperea marginata has been the sole species in Caperea and in the Neobalaenidae (or Cetotheriidae: Neobalaeninae) since its recognition in the mid-1800s, with no obvious fossil relatives reported until Bisconti described the similar Miocene †M. pulchra in 2012. Possible morphological stasis (punctuated equilibrium) in the single lineage of †Miocaperea–Caperea since the late Miocene (7–8 Ma) could explain the low diversity of neobalaenines relative to rorquals (balaenopterids). Strongly pelagic habits could explain the poor fossil record of the Caperea lineage, precluding estimates of former neobalaenine diversity and stratigraphic ranges (e.g. [29–31]). The morphological similarity between †Miocaperea and Caperea raises a taxonomic issue—whether †Miocaperea pulchra is sufficiently different morphologically to be generically distinct from Caperea. For now, we follow the name †Miocaperea pulchra. Interestingly, if †Miocaperea were reconsidered as in the genus Caperea, this long-term morphological stasis between †Miocaperea–Caperea may represent stabilomorphism [32]. Of note, here we consider that living Caperea may be descended from the fossil species †Miocaperea, but Caperea should not be considered as living fossil [33].

Recent debate on Caperea phylogeny [23,34,35] reflects different character selections and interpretations of homology, as results here also indicate (see electronic supplementary material). This highlights the issues of character selection for phylogeny in the first place [36] and recognition of homology [37], as well as the distinctive evolutionary history of Caperea [26]. Perhaps the most persuasive instance of ADRs among marine mammals involves sirenians in the lineage leading to Steller's seacow, Hydrodamalis, as inferred from morphological change in fossils [38]. We show now that phylogenetic approaches might help to recognize ADRs in the †Miocaperea–Caperea lineage, providing a new look at neobalaenine evolution in spite of the sparse fossil record. By exploring broad patterns and processes in baleen whale evolution [21,26], including ADRs (this study), and describing more species (e.g. [12,13,17–19,22,34,35]), a better picture of mysticete evolution—involving the largest animals—will arise.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Kemper, David Stemmer, Neville Pledge, Mary-Anne Binnie (South Australian Museum, Adelaide, Australia) for access to collections and allowing photography during Tsai's visit; Erich Fitzgerald, Nicholas Pyenson and three anonymous reviewers for constructive comments, and the handling editor Paul Sniegowski for advice; Daniel Thomas, Daniel Ksepka and Felix Marx for review and comments; Erich Fitzgerald and Robert Boessenecker for discussion.

Endnote

Institutional abbreviation: SAM, South Australian Museum, Adelaide, Australia. The dagger † indicates an extinct taxon.

Data accessibility

Data are available at doi:10.5061/dryad.21q24.

Author contributions

C.-H.T. designed the research and conducted the phylogenetic analyses. C.-H.T. and R.E.F. collected data, and wrote the paper.

Funding statement

C.-H.T. was supported by a University of Otago Doctoral Scholarship.

Competing interests

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Darwin C. 1859. On the origin of species: by means of natural selections or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life, pp. 502 London, UK: John Murray. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scannella JB, Fowler DW, Goodwin MB, Horner JR. 2014. Evolutionary trends in Triceratops from the Hell Creek Formation, Montana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10 245–10 250. ( 10.1073/pnas.1313334111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foote M, Sepkoski JJ. 1999. Absolute measures of the completeness of the fossil record. Nature 398, 415–417. ( 10.1038/18872) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aze T, Ezard TH, Purvis A, Coxall HK, Stewart DR, Wade BS, Pearson PN. 2011. A phylogeny of Cenozoic macroperforate planktonic foraminifera from fossil data. Biol. Rev. 86, 900–927. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00178.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hennig W. 1966. Phylogenetic systematics. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayrat B. 2005. Ancestor–descendant relationships and the reconstruction of the Tree of Life. Paleobiology 31, 347–353. ( 10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0347:ARATRO]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bretsky SS. 1979. Recognition of ancestor–descendant relationships in invertebrate paleontology. In Phylogenetic analysis and paleontology (eds Cracraft J, Eldredge N.), pp. 113–163. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szalay FS. 1977. Ancestors, descendants, sister groups and testing of phylogenetic hypotheses. Syst. Biol. 26, 12–18. ( 10.1093/sysbio/26.1.12) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cracraft J. 1974. Phylogenetic models and classification. Syst. Biol. 23, 71–90. ( 10.1093/sysbio/23.1.71) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson GJ. 1971. ‘Cladism’ as a philosophy of classification. Syst. Zool. 17, 373–376. ( 10.2307/2412351) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pyenson ND, Goldbogen JA, Vogl AW, Szathmary G, Drake RL, Shadwick RE. 2012. Discovery of a sensory organ that coordinates lunge feeding in rorqual whales. Nature 485, 498–501. ( 10.1038/Nature11135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deméré TA, McGowen MR, Berta A, Gatesy J. 2008. Morphological and molecular evidence for a stepwise evolutionary transition from teeth to baleen in mysticete whales. Syst. Biol. 57, 15–37. ( 10.1080/10635150701884632) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald EMG. 2010. The morphology and systematics of Mammalodon colliveri (Cetacea: Mysticeti), a toothed mysticete from the Oligocene of Australia. Zoolog. J. Linn. Soc. 158, 367–476. ( 10.1111/J.1096-3642.2009.00572.X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlsen K. 1962. Development of tooth germs and adjacent structures in the whalebone whale (Balaenoptera physalus (L.)), with a contribution to the theories of the mammalian dentition. Hvalradets Skrifter 45, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Valen L. 1968. Monophyly or diphyly in the origin of whales. Evolution 22, 37–41. ( 10.2307/2406647) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald EMG. 2012. Archaeocete-like jaws in a baleen whale. Biol. Lett. 8, 94–96. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0690) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okazaki Y. 2012. A new mysticete from the upper Oligocene Ashiya Group, Kyushu, Japan and its significance to mysticete evolution. Bull. Kitakyushu Mus. Nat. Hist. Hum. Hist. A 10, 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders AE, Barnes LG. 2002. Paleontology of the late Oligocene Ashley and Chandler Bridge formations of South Carolina, 3: Eomysticetidae, a new family of primitive mysticetes (Mammalia: Cetacea). Smithson. Contrib. Paleobiol. 93, 313–356. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell ED. 1989. A new cetacean from the Late Eocene La Meseta Formation Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 46, 2219–2235. ( 10.1139/f89-273) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould SJ. 1977. Ontogeny and phylogeny, pp. 501 Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai CH, Fordyce RE. 2014. Juvenile morphology in baleen whale phylogeny. Naturwissenschaften 101, 765–769. ( 10.1007/s00114-014-1216-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bisconti M. 2012. Comparative osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Miocaperea pulchra, the first fossil pygmy right whale genus and species (Cetacea, Mysticeti, Neobalaenidae). Zoolog. J. Linn. Soc. 166, 876–911. ( 10.1111/J.1096-3642.2012.00862.X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fordyce RE, Marx FG. 2013. The pygmy right whale Caperea marginata: the last of the cetotheres. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 1–6. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.2645) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goloboff PA, Farris JS, Nixon KC. 2008. TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics 24, 774–786. ( 10.1111/J.1096-0031.2008.00217.X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foote M. 1996. On the probability of ancestors in the fossil record. Paleobiology 22, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai CH, Fordyce RE. 2014. Disparate heterochronic processes in baleen whale evolution. Evol. Biol. 41, 299–307. ( 10.1007/s11692-014-9269-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gould SJ, Eldredge N. 1993. Punctuated equilibrium comes of age. Nature 366, 223–227. ( 10.1038/366223a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eldredge N, Gould SJ. 1972. Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism. In Models in Paleobiology (ed. Schopf TJM.), pp. 82–115. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, Cooper & Company. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buono MR, Dozo MT, Marx FG, Fordyce RE. 2014. A Late Miocene potential neobalaenine mandible from Argentina sheds light on the origins of the living pygmy right whale. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 52, 787–793. ( 10.4202/app.2012.0122) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzgerald EMG. 2012. Possible neobalaenid from the Miocene of Australia implies a long evolutionary history for the pygmy right whale Caperea marginata (Cetacea, Mysticeti). J. Vert. Paleontol. 32, 976–980. ( 10.1080/02724634.2012.669803) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kemper CM. 2009. Pygmy right whale: Caperea marginata. In Encyclopedia of marine mammals (eds Perrin WF, Wursig B, Thewissen JGM.), pp. 939–941, 2nd edn San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kin A, Błażejowski B. 2014. The horseshoe crab of the genus Limulus: living fossil or stabilomorph? PLoS ONE 9, e108036 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0108036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casane D, Laurenti P. 2013. Why coelacanths are not ‘living fossils’. Bioessays 35, 332–338. ( 10.1002/bies.201200145) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bisconti M. 2014. Anatomy of a new cetotheriid genus and species from the Miocene of Herentals, Belgium, and the phylogenetic and palaeobiogeographical relationships of Cetotheriidae s.s. (Mammalia, Cetacea, Mysticeti). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 1–19. ( 10.1080/14772019.2014.890136) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Adli JJ, Deméré TA, Boessenecker RW. 2014. Herpetocetus morrowi (Cetacea: Mysticeti), a new species of diminutive baleen whale from the Upper Pliocene (Piacenzian) of California, USA, with observations on the evolution and relationships of the Cetotheriidae. Zoolog. J. Linn. Soc. 170, 400–466. ( 10.1111/zoj.12108) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poe S, Wiens JJ. 2000. Character selection and the methodology of morphological phylogenetics. In Phylogenetic analysis of morphological data (ed. Wiens JJ.), pp. 20–36. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall BK. 1994. Homology: the hierarchical basis of comparative biology. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Domning DP. 1978. Sirenian evolution in the north Pacific Ocean. Univ. Calif. Publ. Geol. Sci. 118, 1–176. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at doi:10.5061/dryad.21q24.