Significance

The vertical supply of dissolved Fe (iron) is insufficient compared with the physiological needs of marine phytoplankton in vast swathes of the open ocean. However, the relative importance of the main sources of “new” Fe to the ocean—continental mineral dust, hydrothermal exhalations, and sediment dissolution—and their temporal evolution are poorly constrained. By analyzing the isotopic composition of Fe in marine sediments, we find that much of the dissolved Fe in the central Pacific Ocean originated from hydrothermal and sedimentary sources thousands of meters below the sea surface. As such, these data underscore the vital role of the oceans’ physical mixing in determining if any deeply sourced Fe ever reaches the Fe-starved surface-dwelling biota.

Keywords: marine chemistry, micronutrient cycling, iron biogeochemistry, isotopic fingerprinting, ferromanganese oxides

Abstract

Biological carbon fixation is limited by the supply of Fe in vast regions of the global ocean. Dissolved Fe in seawater is primarily sourced from continental mineral dust, submarine hydrothermalism, and sediment dissolution along continental margins. However, the relative contributions of these three sources to the Fe budget of the open ocean remains contentious. By exploiting the Fe stable isotopic fingerprints of these sources, it is possible to trace distinct Fe pools through marine environments, and through time using sedimentary records. We present a reconstruction of deep-sea Fe isotopic compositions from a Pacific Fe−Mn crust spanning the past 76 My. We find that there have been large and systematic changes in the Fe isotopic composition of seawater over the Cenozoic that reflect the influence of several, distinct Fe sources to the central Pacific Ocean. Given that deeply sourced Fe from hydrothermalism and marginal sediment dissolution exhibit the largest Fe isotopic variations in modern oceanic settings, the record requires that these deep Fe sources have exerted a major control over the Fe inventory of the Pacific for the past 76 My. The persistence of deeply sourced Fe in the Pacific Ocean illustrates that multiple sources contribute to the total Fe budget of the ocean and highlights the importance of oceanic circulation in determining if deeply sourced Fe is ever ventilated at the surface.

Iron (Fe) is the most abundant transition metal in marine phytoplankton, reflecting its importance for a range of biochemical processes such as photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation (1). The high cellular requirements for Fe, coupled with its low solubility and concentrations in seawater, render Fe a limiting nutrient in vast regions of the global ocean (2). In turn, this makes the availability of dissolved Fe a potential controlling factor for changes in atmospheric pCO2 and thereby major oscillations in Earth’s climate. Global biogeochemical models show that more regions of the surface ocean are dominated by circulation-driven dissolved Fe fluxes from below than by surface aerosol fluxes (e.g., refs. 3 and 4). This upward flux of dissolved Fe is itself primarily sourced from three main pathways: dissolution of mineral dust (e.g., ref. 5), submarine hydrothermalism (e.g., refs. 6–8), and sediment dissolution along continental margins (e.g., refs. 9 and 10), with the main removal mechanism being scavenging onto sinking particles (e.g., ref. 11). However, the significance of deeply derived Fe sources—submarine sediment dissolution and hydrothermalism—compared with surface Fe sources (dust dissolution), remains controversial (e.g., refs. 12 and 13). Given the key role of Fe in supporting oceanic primary production, quantifying the relative importance of the various Fe sources—both in the modern ocean and in the geological record—is critical to understanding how micronutrient cycles are related to Earth’s climatic state.

One promising way to trace Fe sources in the modern ocean is with measurements of stable Fe isotopic compositions, where . Recent studies showed that the Fe isotopic composition of seawater is primarily controlled by the relative input of isotopically distinct Fe sources (14, 15), and that these source signatures can be transported and retained over thousands of kilometers within the ocean interior (14). The large range in Fe isotopic compositions observed between different Fe sources (≥4‰) and in seawater (>2‰) should therefore also be reflected in sedimentary archives that faithfully capture the Fe isotopic composition of seawater (14–17).

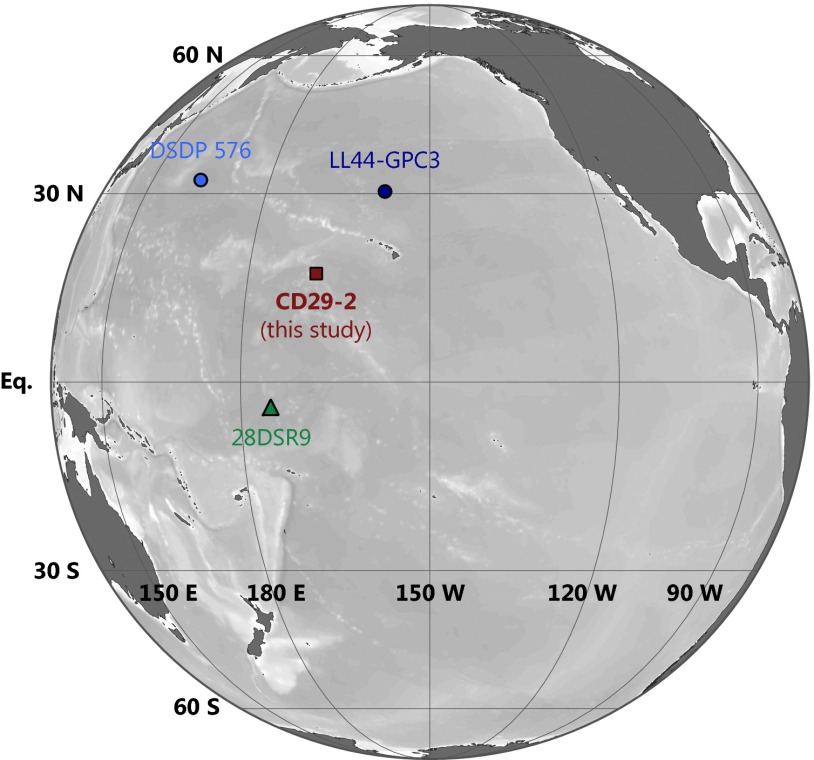

Here, we report a record of from CD29-2, a mineralogically uniform (18) Fe−Mn (ferromanganese) crust collected from the flank of the Karin Ridge at N, W in the central Pacific (ref. 19, Fig. 1). The present water depth of CD29-2 is ∼2,000 m, although the depth at the time when Fe−Mn crust formation commenced was likely m [owing to thermal subsidence (SI Materials and Methods)]. Hydrogenetic Fe−Mn crusts are irregularly layered sedimentary deposits that form through chemical precipitation of Fe and Mn oxides from ambient seawater, forming the Fe oxyhydroxide mineral feroxyhyte (20). Their persistence on rock substrates away from sediment sources that might bury the crust (20) allows other metals to adsorb and become incorporated into Fe−Mn crusts via lattice replacement or coprecipitation with Fe or Mn oxides (21). Detailed elemental stratigraphy showed that CD29-2 is hydrogenetic—rather than hydrothermal or diagenetic—in origin (18). This designation means that the Fe and other metals contained within CD29-2 were sourced from ambient seawater at the time of deposition, rather than diagenetic remobilization of sedimentary metals, or through accretion of proximal hydrothermal vent-derived Fe and Mn oxides.

Fig. 1.

Map of sample locations. Sample CD29-2 was recovered from the flanks of the Karin Ridge at m depth. CD29-2 is an extensively studied and nearly continuous hydrogenetic depositional record spanning the past ∼76 Ma (Fig. 2). The locations of other samples referred to throughout the text and in Fig. 3 are also shown: 28DSR9, a hydrogenetic Fe−Mn crust with a detailed Fe isotopic stratigraphy for the past ∼10 Ma (67); and Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) Site 576 (61) and LL44-GPC3 (62), two continuous Cenozoic records of aeolian deposition. Map drafted in Ocean Data View (68).

Hydrogenetic Fe−Mn crusts are recorders of long-term changes in seawater trace element isotopic chemistry as they grow extremely slowly [ mm⋅My−1 (20)]. Sample CD29-2 has an average growth rate of ∼1.4 mm⋅My−1 (22), with each discrete sample for (between 0.2 and 0.5 mm) integrating between 140 and 350 ky of Earth history. Since the residence time of dissolved Fe in the deep ocean [∼270 y (23)] is less than the mixing time of the oceans [∼1,000 y (24)], our record provides a local history of the central Pacific, rather than of global seawater (Table S1). Postdepositional processes such as diffusional reequilibration with seawater (25) or precipitation of calcium fluorapatite in Fe−Mn crust pore spaces (26) have not affected the Fe isotopic record in CD29-2 (see SI Discussion). Therefore, the Fe isotopic range of CD29-2 (‰ to ‰, with mean and median values of ‰ and ‰, respectively) must reflect primary depositional signatures inherited from Fe dissolved in seawater.

Estimating the Fe Isotopic Fractionation Factor, Its Driving Mechanism, and Variability Through Time

A robust reconstruction of the Fe isotopic history of seawater from Fe−Mn crusts requires that the fractionation factor between Fe−Mn crusts and seawater, , is accurately known, is unaffected by ambient environmental conditions, and has remained relatively constant through time. Stable isotopic offsets between Fe−Mn crusts and seawater are common for many elements, and likely result from differences in the relative binding strength between chemical species dissolved in seawater and incorporated in Fe−Mn crusts (e.g., ref. 27). We calculated the fractionation factor, defined as , by comparing of the surface scrapings of nine North Atlantic Fe−Mn crusts (28) with nearby seawater measurements from the recent US GEOTRACES North Atlantic GA03 Zonal Transect (15) (topology shown in Fig. S1A). The mean, unweighted fractionation factor was calculated as ‰ (2 SE, ), and shows no obvious dependence on crust–seawater distance, sample depth, or ambient dissolved [Fe] (Fig. S1 B, C, and D, respectively). We chose to report the uncertainty about the mean value as two SEs owing to the remarkable coherence and unidirectional nature of calculated Fe−Mn crust–seawater offsets, as well as the large number of independent estimates of (Table S2).

Comparison of the Fe isotopic composition of modern Fe−Mn crust growth surfaces and nearby ambient seawater indicates that Fe bound in Fe−Mn crusts is isotopically lighter than that dissolved in seawater (Fig. S1), indicative of stronger binding of Fe in seawater than in Fe−Mn crusts at equilibrium (e.g., ref. 29). Given the importance of siderophore-like strong Fe-binding ligands in stabilizing dissolved Fe in seawater (30, 31), it is extremely likely that organic ligands play an important—if not dominant—role in setting . Several studies have documented that isotopically heavy Fe will preferentially associate with organic ligands during equilibration between aqueous Fe(III) and Fe–ligand complexes (32–34). The binding strength of the Fe–ligand complex can modulate the magnitude of Fe isotopic fractionation, with stronger ligands—and thus stronger bonding environments—favoring larger equilibrium Fe isotopic fractionation factors. Analogous behavior has also been identified for Cu (35), which likely explains both the direction and magnitude of Cu isotopic fractionation between Fe−Mn crusts and seawater (36). The calculated value of of ‰ is essentially identical to the empirically determined between inorganic dissolved Fe(III) and Fe–siderophore complexes of −0.60 ± 0.15‰ (32). The remarkable agreement between Fe isotopic fractionation factors determined by experiment (32) and those observed between naturally occurring Fe−Mn crusts and seawater (Fig. S1) suggests that organic ligands may exert the dominant control on .

Interpretation of Fe−Mn crust-derived records of seawater rely on having been constant through time. If ligands are indeed exerting a significant influence on Fe isotopic fractionation in seawater, it is important to understand how evolutionary changes in the dominant Fe-binding ligands may have also affected . To address this issue, we examined the evolutionary history of a component from each of two common siderophore biosynthetic pathways, as siderophores are thought to contribute to the oceanic Fe ligand inventory (37): enterobactin synthase subunit F (EntF) and desferrioxamine E biosynthesis protein DesA (Tables S3 and S4). While these are unlikely to be the only ligands in seawater, these ligands—and in particular, DFO (desferrioxamine)—are good analogs to other marine Fe ligands for several reasons: (i) The DFO class of ligands has been shown to exist in seawater (38); (ii) DFO possesses similar conditional Fe binding constants to natural marine Fe ligands (39); and (iii) The Fe isotopic fractionation factor between dissolved Fe(III) and Fe–DFO complexes of of ‰ (32) is identical to , within uncertainty. Analysis of sequence alignments of the genes encoding these proteins in extant microbes demonstrates that siderophore biosynthesis genes diverged from a common ancestor well before the 76 My timespan of interest in this study (SI Discussion and Fig. S2). Given this finding, we contend that Fe-binding ligands have been present in seawater over the past 76 My, and likely far longer. Since the mineralogy of CD29-2 is invariant over this time period (18), it follows that the differences in binding strength—and therefore the equilibrium —between ligand-stabilized Fe in seawater and Fe bound in CD29-2 has also remained constant for at least 76 My. That there are also no resolvable Fe isotopic effects related to Fe transport distance, water depth, or ambient [Fe] on in the modern ocean (Fig. S1), we conclude that the use of a temporally constant of ‰ for the past 76 My is justified by all available oceanographic, experimental, and genomic data.

Controls on the Fe Isotopic Composition of Seawater

It is worthwhile to briefly review what is currently known about the Fe isotopic systematics of the major Fe sources to the modern ocean, as this information is used as the interpretive framework for understanding the seawater record contained within CD29-2. The Fe isotopic composition of seawater is thought to be primarily controlled by the relative input of local, isotopically distinct Fe sources, modulated by secondary modification processes (Fig. 2A), and mixing by oceanic circulation (14, 15). The persistence of primary Fe isotopic signatures along distinct water masses spanning thousands of kilometers suggests that the oceans’ internal cycling of Fe through biological uptake and exchange with sinking particles exerts only a minimal influence on dissolved (14, 15). Thus, the Fe isotopic composition of a water mass appears to be primarily governed by the Fe isotopic composition of the dominant Fe source to that water mass, in addition to any source Fe isotopic modification processes at the time of Fe addition. Iron isotopic measurements can therefore be used to help elucidate the ultimate sources of Fe to the ocean, and in particular the deep open ocean, where the dominant sources of Fe are still debated (e.g., refs. 7 and 40–42).

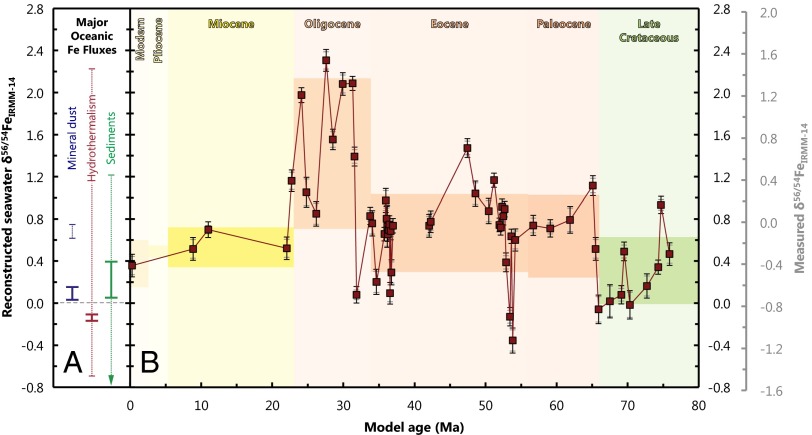

Fig. 2.

An Fe isotopic history of central Pacific seawater over the past 76 Myr. (A) Fe isotopic compositions of the major oceanic Fe fluxes. The bold lines represent the end-member compositions of each flux: continental crust, hydrothermal fluids, and nonreductive sediment dissolution. [A second end-member for reductive sediment dissolution of ‰ is not shown (9).] Numerous processes have been shown to modify end-member Fe isotopic compositions; the dashed lines illustrate the observed range of Fe isotopic compositions for each flux resulting from secondary modification processes, discussed in the main text. (B) An Fe isotopic history of central Pacific seawater recovered from CD29-2 spanning the past 76 Ma. The solid line links the measurements in relative chronological order; the break in the solid line between 37 and 42 Ma signifies a probable hiatus in the crust growth (22). The surface measurement (at ∼0 Ma) is from Levasseur et al. (28). The error bars represent the analytical (gray) and propagated analytical and calculated (black) uncertainties in . The light-colored shading indicates the boundaries between relevant geological epochs. Within each epoch, measurements of have been binned, with the darker shading corresponding to 1 SD either side of the mean value for that epoch. The shaded region labeled “Modern” corresponds to the mean and SD of the surface scrapings of globally distributed Fe−Mn crusts (28) but has been expanded to cover the Quaternary for the sake of clarity (28). [Pliocene and Miocene averages also include Fe−Mn crust data from Chu et al. (67); see Fig. 3.] The grayed-out scale to the right of the figure shows the measured Fe isotopic ratios for CD29-2 that have not been corrected for ‰.

The end-member Fe isotopic composition of the three major Fe sources to the open ocean—mineral aerosol or “dust,” seafloor sediment dissolution, and hydrothermalism—are summarized in Fig. 2A (bold lines). The major surface Fe source, dust, is characterized by ‰ (43), identical to the average Fe isotopic composition of crustal rocks [‰ (44)]. Deeply sourced Fe from dissolution of shelf sediments and hydrothermalism has distinct and variable Fe isotopic compositions. Reductive dissolution of marginal sediments delivers isotopically light Fe to seawater, with ‰ (9), whereas nonreductive dissolution transfers Fe with a continental crust-like composition of ‰ (10). End-member hydrothermal fluid has been measured ‰ (45, 46), with a small but significant fraction of this Fe escaping precipitation and becoming stabilized in seawater as Fe(III) (7, 41).

For each of these three major oceanic Fe fluxes, secondary modification processes have been shown to affect the Fe isotopic composition of ligand-stabilized Fe in seawater (dashed lines in Fig. 2A). The Fe isotopic composition of dust-derived Fe in seawater appears to be isotopically heavier than crustal rocks by ‰ at ‰ (ref. 15, Fig. 2A). In the absence of ligands, total digests and leaching experiments on aerosol particulates have shown that Fe leached from dust possesses ‰ (43). The 0.6‰ offset between Fe bound in dust particles and dust-derived dissolved Fe in seawater is thought to result from the equilibrium isotopic partitioning of isotopically heavy Fe into strongly bound ligand-stabilized dissolved Fe(III) during dust dissolution (15). This interpretation is consistent with experimental studies of Fe isotopic fractionation during mineral dissolution (47) and during dissolved Fe(III)–ligand Fe isotopic partitioning experiments (33, 34). Since Fe-binding organic ligands have an ancient biological origin that predates the base of CD29-2 (see SI Discussion), it is likely that the Fe isotopic offset between dust particles and ligand-stabilized dust-derived Fe in seawater [‰ (15, 43, 44)] has remained constant over the course of our 76-My record. It is worth noting that and are identical, within uncertainty, lending further support to the notion that a common ligand-mediated mechanism controls both Fe isotopic offsets.

For deep Fe sources—hydrothermalism and sediment dissolution—Fe isotopic modification processes have also been identified, although the mechanisms involved are different from those for mineral aeorsol Fe isotopic modification. The most important modification processes identified in deep settings is the precipitation of dissolved Fe in either oxide or sulfide forms, depending on local seawater conditions. These two Fe-precipitating pathways impart large and distinct Fe isotopic fractionations of opposite signs, as Fe oxides generally favor precipitation of isotopically heavy Fe [i.e., (45)] and Fe sulfides exclusively favor incorporation of isotopically light Fe [i.e., (48–50)]. Residual, dissolved Fe will thus become isotopically heavier as a result of Fe sulfide precipitation, and isotopically lighter as a result of Fe oxide precipitation. Field studies have shown that Fe sulfide precipitation in continental margin sediments (10, 49) and at hydrothermal vent sites (46, 51) can drive the Fe isotopic composition of residual Fe, and thereby deep water Fe fluxes, toward heavier by over ‰ (52) compared with the end-member compositions (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, formation of isotopically heavy Fe oxide precipitates around hydrothermal vents has also been shown to drive the delivery of isotopically light Fe to the deep ocean (e.g., refs. 15 and 45).

Given the large range of Fe isotopic variability between different Fe sources (Fig. 2A) and observed in the modern ocean (14–16), we should naturally expect that changes in the dominant sources of Fe to the ocean with time will be accompanied by large shifts in the Fe isotopic composition of seawater. Shifts in seawater with time will thus depend on the relative input of different Fe sources to the ocean and the extent of their modification before stabilization in seawater (Fig. 2).

An Fe Isotopic History of Central Pacific Seawater

Examination of our record of reveals large changes in the Fe isotopic composition of central Pacific seawater over the past 76 My (Fig. 2B). Although much of the record lies outside of the field defined by source end-member (Fig. 2A), when the aforementioned source modification processes are taken into account, even the most extreme values fall within the Fe isotopic range defined by modern Fe fluxes (Fig. 2). Overall, the Fe isotopic record of seawater reveals significant temporal variability, which suggests that the dominant Fe sources to the ocean have also varied over time, and that multiple Fe sources contribute to the total Fe budget of the central Pacific Ocean.

The large intraepoch variation seen in past seawater necessitates that the dominant Fe sources to the Pacific have changed through time (Fig. 2). Assuming a fixed dust value of ‰ throughout the past 76 My, it is clear that more than 75% of the record is outside of the field defined by mineral aerosol (Fig. 3). Isotopic mixing considerations (27) demand that Fe isotopic values observed outside of this narrow range must originate from mixing with other Fe sources with different Fe isotopic compositions (Fig. 2B). Deep sources have been documented to possess that is highly variable and distinct from dust (Fig. 2A). Thus, the large range of Fe isotopic compositions observed over the last 76 My require the addition of a quantitatively significant deeply sourced Fe pool to the central Pacific Ocean, such as sediment dissolution or hydrothermalism (Fig. 3). Applying a constant dust-derived ‰ (15), we note 12 distinct events where seawater Fe isotopic compositions cross through the dust value (Fig. 3). To change seawater in the past from ‰ to ‰ (and vice versa) requires the input of an isotopically distinct deep Fe source term to the central Pacific, as addition of more dust will simply drive the record toward ‰. That these events are not restricted to any particular epoch (although notably absent from the mid-Miocene onward) suggests deeply sourced Fe has been a significant and persistent component of the total Fe inventory of the Pacific Ocean throughout the past 76 My (Fig. 3).

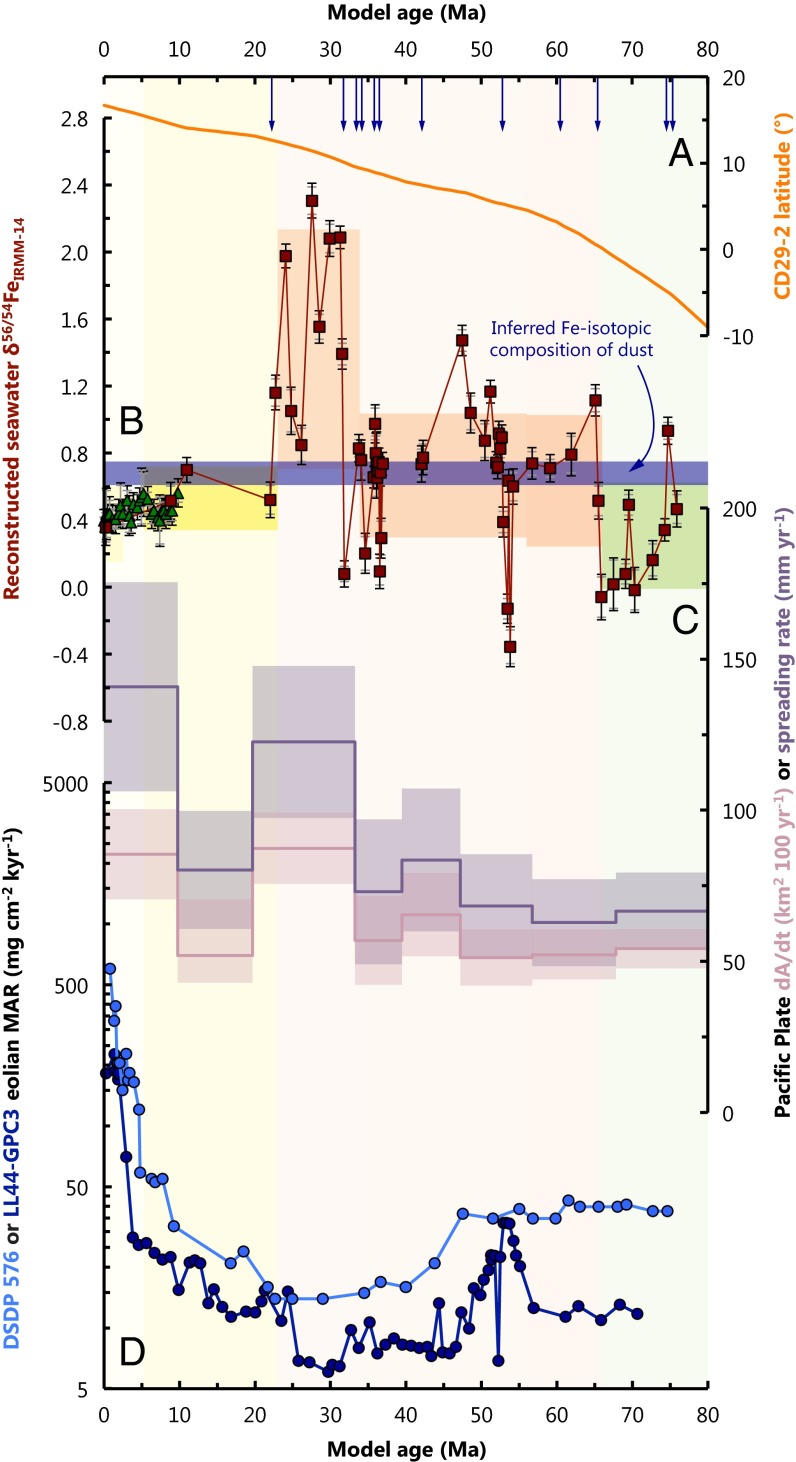

Fig. 3.

Persistence of deeply sourced Fe in the Pacific Ocean. (A) Latitude of CD29-2 based on nearby DSDP locations (69). (B) The Fe isotopic history of central Pacific seawater recovered from Fe−Mn crust CD29-2 (squares). The high-resolution Fe isotopic stratigraphy from 28DSR9 (67) (triangles) spanning the past Ma is also shown, renormalized to IRMM-14 and corrected for ‰ (location shown in Fig. 1). Vertical arrows indicate the 12 instances where the Fe isotopic composition of seawater transits the Fe isotopic composition of dust (horizontal bar) (15). (C) Reconstructed Pacific Plate seafloor generation rate (58). Both the spreading rate (millimeters per year) and change in relative seafloor area (dA/dt, in square kilometers per hundred years) are shown, as the total amount of new crust generated depends on total ridge length and spreading rate. (D) Records of eolian deposition in the North Pacific Ocean from DSDP 576 (61) and LL44-GPC3 (62); note the logarithmic scale. The interrelationships between these three records are discussed in detail in SI Discussion.

Understanding Sustained Changes in the Fe Isotopic Composition of Central Pacific Seawater

The non-dust-like Fe isotopic compositions recorded by CD29-2 necessitate a persistent influence of deep Fe sources to the total Fe inventory of central Pacific seawater over the past 76 My. It is further possible to interpret some of the sustained excursions in (i.e., the interepoch variability) by understanding the location history of CD29-2 and how this relates to probable changes in the supply rate of the major Fe sources to the ocean (Fig. 3). A detailed paleogeography of CD29-2 is discussed in Klemm et al. (53). Briefly, CD29-2 was situated at at the time of its formation (76 Ma), crossed the equator around the K–Pg boundary (Cretaceous–Paleogene; 66 Ma), and has gradually progressed to its present location at ∼16°N (Fig. 3A). Thermal subsidence of the underlying oceanic lithosphere has likely increased the water depth from m to m over the past 76 My, with the most rapid changes in depth occurring soon after CD29-2 began precipitating (see SI Materials and Methods). With these considerations in mind, we discuss below the three most prominent features of the long-term Fe isotopic record: the excursion to extremely heavy during the Oligocene, the absence of intraepoch variation after the mid-Miocene, and possible isotopically light values during the Late Cretaceous (Fig. 3). The Oligocene data are discussed in detail in the SI Discussion but are summarized here.

The Oligocene data are best explained by a large and persistent increase in the hydrothermal contributions to the total Fe budget of water masses bathing CD29-2 during this epoch (Fig. 3). The extremely heavy of up to ‰ necessitates that there were significant Fe isotopic source modification processes that were able to deliver isotopically heavy Fe to the ocean without “choking off” the Fe supply. Modification of hydrothermally sourced Fe by precipitation of isotopically light Fe sulfides seems an obvious candidate for such a process (e.g., refs. 46 and 51 and SI Discussion). Hydrothermal vents can exude fluids with micromolar to millimolar Fe concentrations (54), and the precipitation of Fe sulfides from hydrothermal fluids—even at high temperatures—can result in significant Fe isotopic modification of Fe fluxes (e.g., ref. 46 and SI Discussion). Moreover, recent studies have documented distal transport of hydrothermally sourced Fe thousands of kilometers across the Pacific that furthermore resemble the distributions of hydrothermally derived helium anomalies (e.g., refs. 55 and 56). Assuming that the modern correspondence between seafloor generation rate and hydrothermal fluid fluxes (57) was also valid in the past, it is tempting to speculate that this shift to heavy Fe isotopic compositions in the Oligocene was driven by the approximate doubling of the rate of seafloor generation in the Pacific basin during this epoch (ref. 58, Fig. 3C). Conversely, CD29-2 was likely situated at ∼11°N during the Oligocene (Fig. 3A), which is now bathed by a distal jet of hydrothermally influenced deep waters between m and m [evidenced by mantle-derived helium anomalies (59)]. Assuming that the vent systems at 9°N–10°N along the East Pacific Rise (EPR) remained active during the Oligocene, and that the predominantly east-to-west geostrophic flow at these depths also persisted at this time (60), it is conceivable that CD29-2 simply moved through a distal plume of hydrothermally influenced deep waters. Since there are no textural or elemental indications of hydrothermal input to CD29-2 at this—or any other—time (18) during its ∼76-My growth history (22), the Fe isotopic systematics of CD29-2 require an unprecedented degree of Fe isotopic source modification to waters bathing CD29-2 during this epoch. However, testing whether or not this isotopically heavy Fe reflects a Pacific basin-wide increase in hydrothermally derived Fe during the Oligocene, or simply a local phenomenon, will require a better spatial resolution of seawater from other Fe−Mn crusts in the region.

An important feature of the record is that the intraepoch shifts in to values above and below the dust end-member appear to cease around the mid-Miocene (arrows in Fig. 3). The large Fe isotopic shifts seen throughout the rest of the record must be related to non-dust-derived deep Fe sources such as hydrothermalism and marginal sediment dissolution. However, during the past 10–20 My, the average Fe isotopic composition of central Pacific seawater recorded by CD29-2 and 28DSR9 became largely invariant at ‰ ( SD). This switch to relative Fe isotopic homogeneity over the past 10–20 My is roughly coincident with a sharp increase in eolian dust deposition in the central and North Pacific (refs. 61 and 62, Fig. 3D), and likely reflects a reduction in the importance of deeply sourced Fe to local Fe budgets since that time. Since dust-derived Fe is thought to possess ‰ (15), the Fe isotopic chemistry of CD29-2 is consistent with the interpretation that dust has provided a significant portion of the central Pacific Fe inventory from ∼10−20 Ma to the present day. However, the small difference between seawater (∼+0.4‰; inferred from Fe−Mn crusts) and the dust end-member (∼+0.7‰) of ∼0.3‰ is indicative of an influence from a secondary, isotopically light Fe source such as reductive sediment dissolution (63) or Fe oxide-influenced hydrothermalism (45).

The sustained light Fe isotopic ratios of the Late Cretaceous are consistent with an influence from continental margin-sourced Fe, or hydrothermalism modified by Fe oxide precipitation to waters bathing CD29-2 (Fig. 3). Reductive and nonreductive dissolution of sediments along continental margins contribute Fe to the oceans with light end-member Fe isotopic compositions of ‰ and ‰, respectively (refs. 9 and 10, Fig. 2A). Analogous to the Fe sulfide modification processes described above, hydrothermal modification by Fe oxide precipitation could also facilitate the release of isotopically light Fe to seawater (15, 45). Although it is currently not possible to distinguish between these two deep sources using , both of these probable sources possess substantially different Fe isotopic fingerprints compared with surface dust deposition, thus ruling out a major atmospheric Fe contribution to seawater bathing CD29-2 during the Late Cretaceous (Fig. 2). At that time, CD29-2 was likely at water depths m (SI Materials and Methods), situated between ∼6°S and the Equator (ref. 53, Fig. 3A). This is somewhat above the buoyant plume height of most EPR-derived helium anomalies (59), such that a shallower, marginal sedimentary Fe source is more likely responsible for controlling ambient . In the modern ocean, significant quantities of reduced (64), bioavailable (65), and isotopically light Fe (9, 63) are released under low-oxygen conditions associated with highly productive western continental margins (66). As such, the lighter Fe isotopic compositions seen by CD29-2 in the Late Cretaceous, compared with the ∼+0.3‰ heavier values seen throughout much of the Cenozoic, indicate a greater importance of shelf sediment dissolution to Fe budgets before the K–Pg boundary (Fig. 3).

Overall, the record illustrates the utility of to distinguish between surface and deep Fe sources in sedimentary archives. Furthermore, the remarkable degree of seawater Fe isotopic variation throughout the record is encouraging because it permits the identification and tracing of distinct Fe sources, their isotopic modification, and provinciality in the ocean over geological time.

Conclusions and Outlook

The Fe isotopic data for CD29-2 illustrate a dynamic Fe cycle in the central Pacific Ocean over the past 76 Myr. Isotopic mixing considerations demand a persistent and significant influence from deeply sourced Fe to the waters bathing CD29-2 throughout the entire record. Deeply sourced Fe may have even contributed the majority of the Fe during certain epochs, such as during the Oligocene, underscoring the importance of oceanic circulation in controlling the spatial extent of deeply sourced Fe and its contribution to basin-scale Fe budgets. However, it is clear that more records of Fe isotopic compositions from other Fe−Mn crusts are required to examine the provinciality of oceanic Fe sources in the past; the long-term record from CD29-2 is merely the first step toward this objective.

Reconstructions of oceanic Fe sources can reveal much about the ocean’s Fe cycle in the past, but it is clear that there is still much to learn. For example, what is the maximum lateral extent that dissolved signatures can persist across the ocean? Are there locations in the modern open ocean where dissolved exceeds ‰? Did the deeply sourced Fe of the Oligocene ever ventilate at the surface? Is deeply sourced Fe an important contributor to the total Fe inventory in other ocean basins? Are the changes in the supply ratio of different Fe sources to the ocean responding to major climatic changes, or driving them? All of these questions can be tackled with a greater spatial coverage of dissolved in the modern ocean and by performing further paleoceanographic studies of past seawater in other ocean basins. Coupling these currently scant Fe isotopic observations to models of global Fe biogeochemistry will help to iron out these issues, and will refine our understanding of the role that different Fe sources play in modulating global climate.

Materials and Methods

The samples of CD29-2 analyzed in this study were previously collected for Tl and Os isotopic investigations, with discrete samples taken via microdrilling. The age model for the crust was determined by matching the Re decay-corrected Os isotopic ratio of each discrete sample with the known Os isotopic evolution of seawater. Sample aliquots were then purified for Fe isotopic analysis using anion exchange column chemistry and converted to nitrate form before mass spectrometric analysis. Iron isotopic analyses were carried out on a Nu Instruments Nu Plasma HR multiple-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer at the University of Oxford. Corrections for instrumental mass bias and isobaric overlap of on were performed by standard–sample bracketing and monitoring , respectively. Mass dependence, reproducibility, and accuracy were evaluated by analysis of various internal and external reference standards and found to be in excellent agreement with previously published values. Further description of methods and samples is available in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. N. Schmidt, T. van de Flierdt, T. M. Conway, W. B. Homoky, P. E. Lerner, J. D. Owens, S. Severmann, and—in particular—J. N. Fitzsimmons for some lively discussions; K. E. Egan and F. Poitrasson for constructive comments on an earlier version of this manuscript; and the editor and several anonymous reviewers for helping us to craft a substantially improved paper. T.J.H. was supported by the Postdoctoral Scholar Program at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, with funding provided by the Doherty Foundation and the Ocean and Climate Change Institute. H.M.W. was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (NE/F014295/1) and the European Research Council (ERC) (306655, HabitablePlanet). M.A.S. is grateful for support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (3782). A.N.H. acknowledges the ERC for supporting isotopic research at the University of Oxford.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1420188112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Twining BS, Baines SB. The trace metal composition of marine phytoplankton. Annu Rev Mar Sci. 2013;5:191–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-121211-172322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd PW, et al. Mesoscale iron enrichment experiments 1993−2005: synthesis and future directions. Science. 2007;315(5812):612–617. doi: 10.1126/science.1131669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aumont O, Maier-Reimer E, Blain S, Monfray P. An ecosystem model of the global ocean including Fe, Si, P colimitations. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2003;17(2):1060. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misumi K, et al. The iron budget in ocean surface waters in the 20th and 21st centuries: Projections by the Community Earth System Model version 1. Biogeoscience. 2014;11:33–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jickells TD, et al. Global iron connections between desert dust, ocean biogeochemistry, and climate. Science. 2005;308(5718):67–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1105959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagliabue A, et al. Hydrothermal contribution to the oceanic dissolved iron inventory. Nat Geosci. 2010;3:252–256. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sander SG, Koschinsky A. Metal flux from hydrothermal vents increased by organic complexation. Nat Geosci. 2011;4:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito MA, et al. Slow-spreading submarine ridges in the South Atlantic as a significant oceanic iron source. Nat Geosci. 2013;6:775–779. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Severmann S, McManus J, Berelson WM, Hammond DE. The continental shelf benthic iron flux and its isotope composition. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2010;74:3984–4004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homoky WB, John SG, Conway TM, Mills RA. 2013. Distinct iron isotopic signatures and supply from marine sediment dissolution. Nat Commun 4:2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wu J, Boyle E, Sunda W, Wen LS. Soluble and colloidal iron in the oligotrophic North Atlantic and North Pacific. Science. 2001;293(5531):847–849. doi: 10.1126/science.1059251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fung IY, et al. Iron supply and demand in the upper ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2000;14:281–295. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore JK, Doney SC, Glover DM, Fung IY. Iron cycling and nutrient-limitation patterns in surface waters of the World Ocean. Deep Sea Res Part II. 2001;49:463–507. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radic A, Lacan F, Murray JW. Iron isotopes in the seawater of the equatorial Pacific Ocean: New constraints for the oceanic iron cycle. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2011;306:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conway TM, John SG. Quantification of dissolved iron sources to the North Atlantic Ocean. Nature. 2014;511(7508):212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacan F, et al. Measurement of the isotopic composition of dissolved iron in the open ocean. Geophys Res Lett. 2008;35(24):L24610. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens JD, et al. Iron isotope and trace metal records of iron cycling in the proto-North Atlantic during the Cenomanian-Turonian oceanic anoxic event (OAE-2) Paleoceanography. 2012;27(3):PA3223. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank M, O’Nions RK, Hein JR, Banakar VK. 60 Myr records of major elements and Pb–Nd isotopes from hydrogenous ferromanganese crusts: Reconstruction of seawater paleochemistry. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1999;63:1689–1708. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hein JR, et al. Farnella cruise F7-86-HW, cobalt-rich ferromanganese crust data report for Karin Ridge and Johnston Island, central Pacific. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep. 1987;87-663:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hein J, et al. Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts in the Pacific. In: Cronan DS, editor. Handbook of Marine Mineral Deposits. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2000. pp. 239–279. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koschinsky A, Hein JR. Uptake of elements from seawater by ferromanganese crusts: Solid-phase associations and seawater speciation. Mar Geol. 2003;198:331–351. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen SG, et al. Thallium isotope evidence for a permanent increase in marine organic carbon export in the early Eocene. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2009;278:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergquist BA, Wu J, Boyle EA. Variability in oceanic dissolved iron is dominated by the colloidal fraction. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2007;71:2960–2974. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broecker WS, Peng TH. 1982. Tracers in the Sea (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Palisades, NY)

- 25.Henderson GM, Burton KW. Using (234U/238U) to assess diffusion rates of isotope tracers in ferromanganese crusts. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1999;170:169–179. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hein JR, et al. Two major Cenozoic episodes of phosphogenesis recorded in equatorial Pacific seamount deposits. Paleoceanography. 1993;8:293–311. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson CM, Beard BL, Albarède F. 2004. Geochemistry of Non-traditional Stable Isotopes, Rev. Mineral. Geochem. (Mineral. Soc. America, Washington, DC), Vol 55.

- 28.Levasseur S, Frank M, Hein JR, Halliday AN. The global variation in the iron isotope composition of marine hydrogenetic ferromanganese deposits: Implications for seawater chemistry? Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2004;224:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson CM, Beard BL, Albarede F. 2004. Overview and general concepts. Geochemistry of non-traditional stable isotopes, eds Johnson CM, Beard BL, Albarede F, Rev. Mineral. Geochem. (Mineral. Soc. America, Washington, DC), Vol 55, pp 1–24.

- 30.van den Berg CMG. Evidence for organic complexation of iron in seawater. Mar Chem. 1995;50:139–157. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraemer SM. Iron oxide dissolution and solubility in the presence of siderophores. Aquat Sci. 2004;66:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dideriksen K, Baker J, Stipp SLS. Fe isotope fractionation between inorganic aqueous Fe (III) and a Fe siderophore complex. Mineral Mag. 2008;72:313–316. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dideriksen K, Baker JA, Stipp SLS. Equilibrium Fe isotope fractionation between inorganic aqueous Fe (III) and the siderophore complex, Fe (III)-desferrioxamine B. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2008;269:280–290. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan JLL, Wasylenki LE, Nuester J, Anbar AD. Fe isotope fractionation during equilibration of Fe-organic complexes. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(16):6095–6101. doi: 10.1021/es100906z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan BM, Kirby JK, Degryse F, Scheiderich K, McLaughlin MJ. Copper isotope fractionation during equilibration with natural and synthetic ligands. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(15):8620–8626. doi: 10.1021/es500764x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Little SH, Sherman DM, Vance D, Hein JR. Molecular controls on Cu and Zn isotopic fractionation in Fe–Mn crusts. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2014;396:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbeau K, Rue EL, Bruland KW, Butler A. Photochemical cycling of iron in the surface ocean mediated by microbial iron(III)-binding ligands. Nature. 2001;413(6854):409–413. doi: 10.1038/35096545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mawji E, et al. Hydroxamate siderophores: Occurrence and importance in the Atlantic Ocean. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(23):8675–8680. doi: 10.1021/es801884r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rue EL, Bruland KW. Complexation of iron (III) by natural organic ligands in the Central North Pacific as determined by a new competitive ligand equilibration/adsorptive cathodic stripping voltammetric method. Mar Chem. 1995;50:117–138. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyle EA. What controls dissolved iron concentrations in the world ocean?—A comment. Mar Chem. 1997;57:163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett SA, et al. The distribution and stabilisation of dissolved Fe in deep-sea hydrothermal plumes. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2008;270:157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toner BM, et al. Preservation of iron(II) by carbon-rich matrices in a hydrothermal plume. Nat Geosci. 2009;2:197–201. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waeles M, Baker AR, Jickells T, Hoogewerff J. Global dust teleconnections: Aerosol iron solubility and stable isotope composition. Environ Chem. 2007;4:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beard BL, et al. Application of Fe isotopes to tracing the geochemical and biological cycling of Fe. Chem Geol. 2003;195:87–117. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Severmann S, et al. The effect of plume processes on the Fe isotope composition of hydrothermally derived Fe in the deep ocean as inferred from the Rainbow vent site, Mid-Atlantic Ridge, 36°14’N. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2004;225:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rouxel O, Shanks WC, III, Bach W, Edwards KJ. Integrated Fe-and S-isotope study of seafloor hydrothermal vents at East Pacific Rise 9–10°N. Chem Geol. 2008;252(3-4):214–227. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiederhold JG, et al. Iron isotope fractionation during proton-promoted, ligand-controlled, and reductive dissolution of Goethite. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40(12):3787–3793. doi: 10.1021/es052228y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butler IB, Archer C, Vance D, Oldroyd A, Rickard D. Fe isotope fractionation on FeS formation in ambient aqueous solution. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2005;236:430–442. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Severmann S, Johnson CM, Beard BL, McManus J. The effect of early diagenesis on the Fe isotope compositions of porewaters and authigenic minerals in continental margin sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2006;70:2006–2022. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guilbaud R, Butler IB, Ellam RM. Abiotic pyrite formation produces a large Fe isotope fractionation. Science. 2011;332(6037):1548–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.1202924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bennett SA, et al. Iron isotope fractionation in a buoyant hydrothermal plume, 5°S Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2009;73(19):5619–5634. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aquilina A, et al. Diagenetic mobilisation of Fe and Mn in hydrothermal sediments. Mineral Mag. 2013;77:604. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klemm V, Reynolds B, Frank M, Pettke T, Halliday AN. Cenozoic changes in atmospheric lead recorded in central Pacific ferromanganese crusts. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2007;253:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Von Damm KL, et al. Chemistry of submarine hydrothermal solutions at 21°N, East Pacific Rise. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1985;49:2197–2220. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu J, Wells ML, Rember R. Dissolved iron anomaly in the deep tropical–subtropical Pacific: Evidence for long-range transport of hydrothermal iron. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2011;75:460–468. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fitzsimmons JN, Boyle EA, Jenkins WJ. Distal transport of dissolved hydrothermal iron in the deep South Pacific Ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(47):16654–16661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418778111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baker ET, Chen YJ, Phipps Morgan J. The relationship between near-axis hydrothermal cooling and the spreading rate of mid-ocean ridges. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1996;142:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cogné JP, Humler E. Trends and rhythms in global seafloor generation rate. Geochem Geophys Geosyst. 2006;7:Q03011. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lupton J. Hydrothermal helium plumes in the Pacific Ocean. J Geophys Res. 1998;103:15853–15868. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reid JL. On the total geostrophic circulation of the Pacific Ocean: Flow patterns, tracers, and transports. Prog Oceanogr. 1997;39:263–352. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Janecek TR. 1985. Eolian sedimentation in the Northwest Pacific Ocean: A preliminary examination of the data from deep sea drilling project sites 576 and 578. Deep Sea Drilling Project Leg 86, Western North Pacific, Initial Reports DSDP, ed Turner KL (US Gov. Printing Office, Washington, DC), Vol 19, pp 589–603.

- 62.Janecek TR, Rea DK. Eolian deposition in the northeast Pacific Ocean: Cenozoic history of atmospheric circulation. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1983;94:730–738. [Google Scholar]

- 63.John SG, Mendez J, Moffett J, Adkins J. The flux of iron and iron isotopes from San Pedro Basin sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2012;93:14–29. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lam PJ, Bishop JK. The continental margin is a key source of iron to the HNLC North Pacific Ocean. Geophys Res Lett. 2008;35(7):L07608. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bruland KW, Rue EL, Smith GJ, DiTullio GR. Iron, macronutrients and diatom blooms in the Peru upwelling regime: Brown and blue waters of Peru. Mar Chem. 2005;93:81–103. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stramma L, Schmidtko S, Levin LA, Johnson GC. Ocean oxygen minima expansions and their biological impacts. Deep Sea Res Part I. 2010;57:587–595. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chu NC, et al. Evidence for hydrothermal venting in Fe isotope compositions of the deep Pacific Ocean through time. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2006;245:202–217. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schlitzer R. 2011 Ocean Data View. Available at odv.awi.de/. Accessed February 20, 2013.

- 69.Van Andel TH, Heath GR, Moore TC. Cenozoic history and paleoceanography of the central equatorial Pacific Ocean: A regional synthesis of Deep Sea Drilling Project data. Geol Soc Am. 1975;143:1–223. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.