Transport of Fukushima radioactivity across the Pacific

Damage to the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant following the earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan in March 2011 raised concern about the transport of radioactive material across the Pacific Ocean to North American shores. John Norton Smith et al. (pp. 1310–1315) collected samples of seawater in the eastern North Pacific Ocean between June 2011 and February 2014. The authors analyzed the seawater, collected at depths up to 1,000 m, for radioactive isotopes 134Cs and 137Cs, both of which could identify radioactive material originating from Fukushima. The authors detected early signals of elevated radioactivity 1,500 km west of British Columbia, Canada, in June 2012. A year later, the authors detected radioactivity of around 2 Bq/m3 at the Canadian continental shelf, approximately equivalent to twice the pre-Fukushima background activity. Ocean circulation model results that reflect the present experimental data suggest that 137Cs concentrations along the North American Pacific coast will peak at levels of approximately 3–5 Bq/m3 around 2015–2016, before declining to fallout background levels after 2021. The results suggest that Fukushima inputs of radioactivity may return eastern North Pacific water concentrations of 137Cs to the fallout levels that prevailed during the 1980s, but that the levels likely do not represent a threat to human or environment health, according to the authors. — P.G.

Brain effects of late second language learning

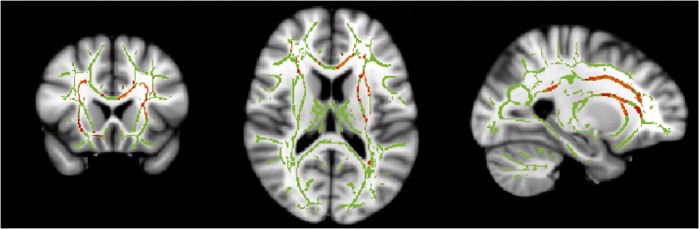

White matter tracts affected by late bilingualism in an immersive environment (red) against a white matter skeleton (green).

Some previous studies have suggested a link between the integrity of the brain’s white matter and the frequent use of a second language among older bilingual individuals and those using a second language since early childhood. To determine whether bilingual adults who learn a second language in an immersive environment—albeit later in life—experience similar brain effects, Christos Pliatsikas et al. (pp. 1334–1337) recruited 20 proficient English speakers who were around 30 years of age, had lived in the United Kingdom for at least 13 months, and had started learning English as a second language around age 10. The authors used brain imaging and an analytical technique called Tract-Based Spatial Statistics to deduce the integrity of white matter in the participants’ brains. Compared with a group of 25 native, monolingual English speakers of similar age, the bilingual participants displayed higher levels of structural integrity in several white matter tracts implicated in language learning and semantic processing, mirroring previous observations among bilingual individuals who had learned and started using a second language early in life. According to the authors, time-course studies on immersive second-language learners might help reveal the onset and pattern of white matter restructuring linked to language learning late in life. — P.N.

Comparing genes and sound units across human populations

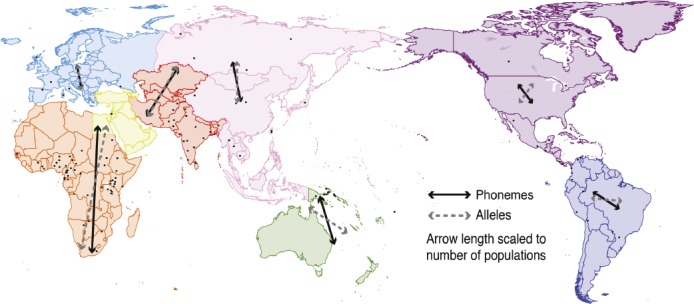

For the Ruhlen phoneme–genome dataset, pairwise geographic distance matrices projected along different axes; within each region, the rotated axis of geographic distance most strongly associated with phonemic distance (black arrows) and genetic distance (gray dashed arrows) is shown.

Language has been proposed to influence gene flow between human populations, but few studies have directly compared the traces of human demographic history in languages and genes. Nicole Creanza et al. (pp. 1265–1272) used statistical methods to examine the imprints of human population history on both DNA microsatellite variations from 246 worldwide populations and inventories of phonemes—sound units that specify the meaning of distinct words—from 2,082 languages. The authors found that regardless of the families to which the languages belonged, geographically close language pairs shared more phonemes than distant language pairs. The analysis also revealed that the pattern of changes of phoneme inventory sizes, unlike genetic changes, did not reflect the human expansion out of Africa that preceded the peopling of the world. Further, in contrast to the well-established detrimental effect of geographic isolation on genetic diversity, isolated languages showed greater evidence of phoneme variation and susceptibility to change than languages with many neighbors. According to the authors, further studies could explain how phonemes evolve along genetic and geographic lines. — P.N.

Effects of BPA and analogs on zebrafish embryos

Previous studies have linked prenatal exposure to bisphenol A (BPA), an endocrine disruptor found in many household products, to childhood behavioral problems, such as aggression and hyperactivity. Cassandra Kinch et al. (pp. 1475–1480) explored the effects of BPA exposure on zebrafish embryos. The authors found that treatment of embryonic zebrafish with a low dose of BPA—1,000-fold lower than the accepted daily exposure for humans—led to a 180% increase in neurogenesis within the hypothalamus, a highly conserved brain region implicated in aggression and hyperactivity. The authors report that exposure to a BPA-analog called bisphenol S (BPS), used in some BPA-free products, resulted in a 240% increase in neurogenesis in the hypothalamus. Further study revealed that restricted BPA/BPS exposure during the neurogenic window caused hyperactive behaviors later in zebrafish larvae. The authors found that BPA-mediated neurogenesis and associated behavioral abnormalities may rely on androgen receptor activation and up-regulation of the enzyme aromatase, rather than relying on estrogen receptor signaling. According to the authors, the findings suggest that BPA-free products that use BPS may not necessarily be safe. — A.G.

Infant napping and memory

Sleep and infant memory. Image courtesy of © Olesia Bilkei/Fotolia

Human infants spend large portions of their days napping, but few studies have uncovered evidence for a causal relationship between sleep and the high levels of growth and development that take place during the first year of life. Sabine Seehagen et al. (pp. 1625–1629) explored whether sleep after learning promotes declarative memory consolidation in 216 healthy, full-term 6- and 12-month-old infants. The authors used a well-established deferred imitation paradigm to test the infants’ abilities to recall a newly learned behavior—removing and manipulating a mitten from a hand puppet—after delays of 4 or 24 hours. Infants who did not take an extended nap after learning were compared with age-matched infants who napped for at least 30 minutes within 4 hours of learning. The infants’ sleep–wake patterns were monitored using a technique called actigraphy. After both delays, only infants who had napped after learning remembered the target actions. Additionally, after the 24-hour delay, infants in the napping group exhibited significantly better recall, compared with infants who had not napped. According to the authors, the study suggests that sleep might enhance the consolidation of declarative memories in the first year of life. — A.G.

Heart rate and fear of terrorism

Pulse evaluation. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Dodo.

Resting heart rate can be used to predict cardiovascular health because elevated heart rates have been associated with systemic inflammation and heart disease. A long-term, abnormally elevated basal heart rate can increase the likelihood of death from all primary causes, but the physical or psychological causes of elevated basal heart rates are not well understood. Shani Shenhar-Tsarfaty et al. (pp. E467–E471) analyzed pulse measurements and the responses of 17,380 healthy adult Israelis to a questionnaire that covered a range of factors that influence morbidity, including body mass index, blood pressure, fitness, smoking, psychological well-being, anxiety, and fear of terror. The authors found that individuals in the study suffered a level of fear from terrorism that predicted the major annual increases of basal heart rate for 4.1% of the study group. Fear of terrorism and elevated basal heart rate were also correlated with levels of C-reactive protein, a biomarker for inflammation. According to the authors, the results suggest a link between long-term exposure to terror threats and inflammation, which is associated with elevated basal heart rates that can increase the risk of mortality. — J.P.J.