Abstract

Aim

The purpose of this study is to evaluate prognosis and surgical management of head and neck melanoma (HNM) and the accuracy of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB).

Patients and Methods

All patients with a primary cutaneous melanoma treated starting from 01/07/1994 to 31/12/2012 in the department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of Bari are included in a electronic clinical medical registry. Within the 90th day from excision of the primary lesion all patients with adverse prognostic features underwent SLNB. All patients with positive findings underwent lymphadenectomy.

Results

out of 680 patients affected by melanoma, 84 (12.35%) had HNM. In the HNM cohort lymphoscintigraphy was performed in 57 patients, 15 of which (26.3%) were positive. The percentage of unfound sentinel lymph node was similar both to the HNM group (5,26%) and to patients with melanoma of different sites (OMS 4,92%). There was a recurrence of disease after negative SLNB (false negatives) only in 4 cases. Recurrence-free period and survival rate at 5 years were worse in HNM cohort.

Conclusion

SLNB of HNM has been for a long time contested due to its complex lymphatic anatomy, but recent studies agreed with this technique. Our experience showed that identification of sentinel lymph node in HNM cohort was possible in 98.25% of cases. Frequency of interval nodes is significantly higher in HNM group. The prognosis of HNM cohort is significantly shorter than OMS one. Finally, this procedure requires a multidisciplinary team in referral centers.

Keywords: Head and neck melanoma, Sentinel lymph node biopsy, Interval nodes

Introduction

Approximately 15%–35% of primary cutaneous melanomas occur in head and neck (1). Head and neck melanoma (HNM) is more frequent in adult males and the most common affected sites are face, neck and ear. If compared with melanoma in other sites (OMS), HNM shows a lower frequency of superficial spreading melanoma, while there is a higher rate of histological subtype of lentigo maligna (2). HNM in children is very rare and it is usually associated with giant congenital nevus (3). At diagnosis, HNM frequently shows a higher Clark level than other ones (2) and this anatomic location is associated with a poorer prognosis. In fact, referring to tumor thickness ranges, the disease-free period is significantly shorter in HNM patients (4), who have a lower 10-year survival rate (2–5). These findings have been related to the early lymphatic involvement of HNM; if effect the 15–20% of patients affected by melanoma of this area has regional lymph node metastases at the time of presentation of the primary tumor (6, 7). Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), introduced by Morton in the early 1990s (8), has become the gold standard for staging all patients affected by melanoma. This technique permit to identify patients with a positive SLNB who may benefit of complete lymphadenectomy and who, after surgery, may be eligible for adjuvant therapy. Furthermore the presence of a positive sentinel lymph node has been demonstrated to be the most important prognostic indicator of disease-free survival (9). In spite of this, the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy in the management of head and neck melanoma has been limited due to several reasons. First of all the lymphatic drainage in the head and neck region is complex, with multiple primary channels and multiple lymph node basins. For this reason many analyses show a substantial discordance between clinically predicted lymphatic drainage pathways and those identified by lymphoscintigraphy(10, 11). This discrepancy causes a higher false negative rates of SLNB of HNM compared with melanomas of other anatomic regions, suggesting a lower accuracy of this technique for HNM (12, 13). Secondarily, excision of these nodes can be technically challenging due to the poor distances among primary lesion and sentinel nodes, making difficult their detection and isolation. Furthermore, a surgical approach must be performed around cranial nerves (VII and XI cranial nerves) and important vascular structures. In addition to this 25–30% of the sentinel nodes are located within the parotid gland, and the concern of facial nerve injury has led many surgeons to prefer superficial parotidectomy to SLNB (14–16). Lastly, the cooperation of experienced pathologists and nuclear medicine staff is essential for the success of the procedure (17). Nevertheless, other recent studies have demonstrated that drainage in this anatomic location is predictable (18–21), but debate remains about the reliability of SLNB performed in the head and neck (HN) region and about its determinant role for prognosis. The aim of our study is to evaluate the accuracy and prognostic value of SLNB in the HN regions in relation with melanomas of other sites (OMS).

Patients and methods

Study population

All patients with a primary cutaneous melanoma treated in the department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of Bari from 01/07/1994 to 31/12/2012 were included in a electronic clinical medical registry after giving informed consent. Patients with another occult primary carcinoma were excluded. Within the 90th day from the excision of the primary lesion, patients affected by a primary melanoma with thickness ≥0.75 mm or with Clark level IV or V, or affected by a thinner tumor associated with adverse prognostic features (regression, ulceration, high mitosis rate) underwent lymphoscintigraphy to identify sentinel node (SN) draining fields. The follow-up period was defined as the time between the melanoma diagnosis date to the last visit occurred until the 30/06/2013, so that the hypothetical shorter-term follow-up was fixed at 6 months. We considered as HNM any lesion located above an horizontal line passing through the superior margin of clavicles and the 7th cervical vertebra.

Mapping, surgical and histological techniques used for lymphatic metastasis diagnosis

The lymphoscintigraphy was performed using technetium 99m nanocolloid HSA (human serum albumin) (22–24) with a dosage of 18–37 MBq, in relationship with procedure time, injected in 4 sites closely around the scar of primary lesion biopsy (22, 23). Ultrahigh resolution collimators were used to ensure that all the territory between the primary melanoma site and the recognized draining node field or fields were imaged and to reduce artifacts. Dynamic and planar images (anterior, posterior and lateral) were acquired using a large field of view dual-headed digital gamma camera both immediately after the radio-labeled colloid injection and after each lymph node visualization to evaluate all drainage basins and the total numbers of the node. A 25-min dynamic image at 1 frame/min in 64×64 matrix in word mode is suggested to determine where the lymphatic collectors are headed. Further 5–10 min static images in word mode 128×128 were acquired over the node field to identify the collectors as they reach the actual SNs. Static images were performed to ensure that all SNs were marked. A static imaging node that appears in a separate field only in a delayed image was considered as a different SN unless it was on the same path in the dynamic scans. A handheld gamma probe was used during surgery to guide SN detection. Multiple sections of each SN were examined by conventional hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and by immunohistochemical stains at both S100 and HMB-45 (25). A positive SN was defined as a lymph node containing melanoma cells detected by either H&E or immunohistochemistry. All histopathologic slides of the interval SNs containing metastatic disease were reevaluated for this study to document the deposit size, tumor penetrative depth, and intranodal tumor volume. The histological presence of metastasis was assessed as micrometastasis (with deposits “2mm) and macrometastasis (with deposits >2mm) affecting the peripheral sinus of a lymph node (24–26). Complete lymph node dissection was performed in all cases with a diagnosis of lymph node metastasis. All patients underwent a clinical and imaging follow-up every six months for the first five years and yearly thereafter.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ baseline characteristics were reported as frequency (percentage) and mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were assessed by the 2 test to compare the results for specific subgroups with those of the rest of the patient population. Recurrence-free survival was defined as the time between the definitive surgical treatment of the primary melanoma and clinical detection of the first recurrence. Follow-up time was defined as the time between definitive surgical treatment of the primary melanoma and the last contact with he patient. Among patients with negative SLNB, only those who presented a recurrence in the same nodal basin analyzed were considered false negatives. Time-to-death analyses were performed using multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models, and risks were reported as hazard ratios (HRs) along with their 95% confidence interval (CI). Survival curves and probabilities were reported according to the Kaplan-Meier method. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Software Release 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Out of 680 patients affected by melanoma, 84 (12.35%) had HNM and 596 had a diagnosis of melanoma in different sites (OMS); the clinical characteristics of these two groups are shown in the Table 1. Regarding HNM group, 34 (40.47%) were located on the face, 14 (16.66%) on the neck, 19 (22.61%) on the ear, and 17 (20.23%) on the scalp. In the HNM cohort there was a significant predominance of males compared with the OMS group. Regarding the histological characteristics, there was less cases of superficial spreading melanoma among the HNM group (36) and, as expected, more cases of lentigo maligna melanoma (12). No further major differences were found about age or primary tumor characteristics between HNM patients and the OMS ones. Fewer patients in the HNM group had a Clark level lower than IV compared with the OMS group and patients with a Breslow thickness greater than 4 mm were more common in the HNM cohort.

Table 1.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENT POPULATION AND PRIMARY TUMOR SITES (*P<0.05).

| Characteristics | OMS patients | HNM patients |

|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 596 (87.65%) | 84 (12.35%) |

|

| ||

| Gender (M), n (%) | 307 (51.51%) | 56 (66.67%)* |

|

| ||

| Age (y) | ||

| Mean | 53.54 | 57.75 |

| Median | 54.20 | 59.36 |

| Range | 9.72 – 88.90 | 13.92 – 95.03 |

|

| ||

| Breslow thickness, n (%) | ||

| ≤2 mm | 448 (75.17%) | 59 (70.24%) |

| 2–4 mm | 81 (13.59%) | 10 (11.90%) |

| ≤4 mm | 67 (11.24%) | 15 (17.90%) |

|

| ||

| Clark level | ||

| I | 8 (1.34%) | 0 |

| II | 57 (9.56%) | 5 (5.95%) |

| III | 110 (18.46%) | 15 (17.86%) |

| IV | 190 (31.88%) | 30 (35.71%) |

| V | 25 (4.19%) | 7 (8.33%) |

| Unknown | 206 (34.56%) | 27 (32.14%) |

|

| ||

| Ulceration, n (%) | ||

| Absent | 414 (69.46%) | 56 (66.67%) |

| Present | 132 (22.15%) | 20 (23.81%) |

| Unknown | 50 (8.39%) | 8 (9.52%) |

|

| ||

| Positive SLNs, n (%) | 138 (23.15%) | 15 (17.86%) |

|

| ||

| Histological subtype | ||

| Superficial spreading | 281 (47.15%) | 36 (42.86%) |

| Nodular | 113 (18.96%) | 18 (21.43%) |

| Lentigo maligna | 2 (0.34%) | 12 (14.29%)* |

| Acrale | 4 (0.67%) | 0 |

| Spitzoid | 7 (1.17%) | 0 |

| Others | 4 (0.67%) | 0 |

| Not otherwise specified | 185 (31.04%) | 16 (19.05%) |

Lymphoscintigraphy was performed in 57 patients of HNM group and in 513 patients with OMS. Positive sentinel nodes were found in 15 out of 57 HNM patients (26.3%) and there was a similar percentage (26.9%) in the OMS group (138/513). The percentage of unfound sentinel lymph node in HNM patients was 1.75% (1/57). A contemporary primary excision and SLNB was performed in 5 cases (8.78%) of HNM patients group.

In the HNM group unusual sentinel lymph nodes (“interval nodes”) were found in 15 cases, 2 of which were positives (13,3%), compared with 38 cases in the OMS group, 11 of which were positive (28,9%). All HNM group of patient with positive SLNB (15 cases out of 57) underwent lymphadenectomy, associated with parotidectomy in 2 cases of sentinel lymph node localized in the parotid gland (27–29).

For the majority of HNM group, sentinel lymph node was found unilaterally, while in 3 cases of median scalp and neck injuries lymphoscintigraphy showed a bilateral drainage of the radioactive isotope with the identification of sentinel lymph nodes bilaterally. Furthermore, 1 patient was positive for sentinel nodes belonging to two different lymphatic basins (neck and axilla), and underwent a lateral cervical and axillary lymph node dissection. Regarding the HNM, only in 4 cases there was a recurrence of disease after BLS negative (false negatives) with detection in 3 cases of lymphatic metastases and in one of subcutaneous in-transit metastasis. In these cases, we performed lymphadenectomy of sentinel lymph node basin.

Currently no neurovascular complications related to surgery have been reported. Regarding prognosis, the HNM group counted 17 deaths and 11 patients alive with disease (AWD) at the end of follow-up period, with mortality (20.24%) and a recurrence (33.33%) rates significantly higher compared to the OMS group (13.93% and 25.33% respectively).

Survival and recurrence-free analysis

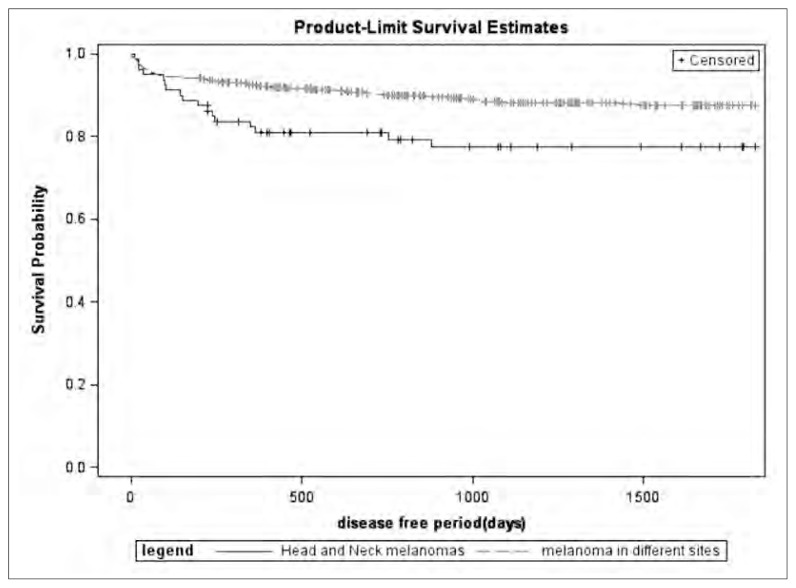

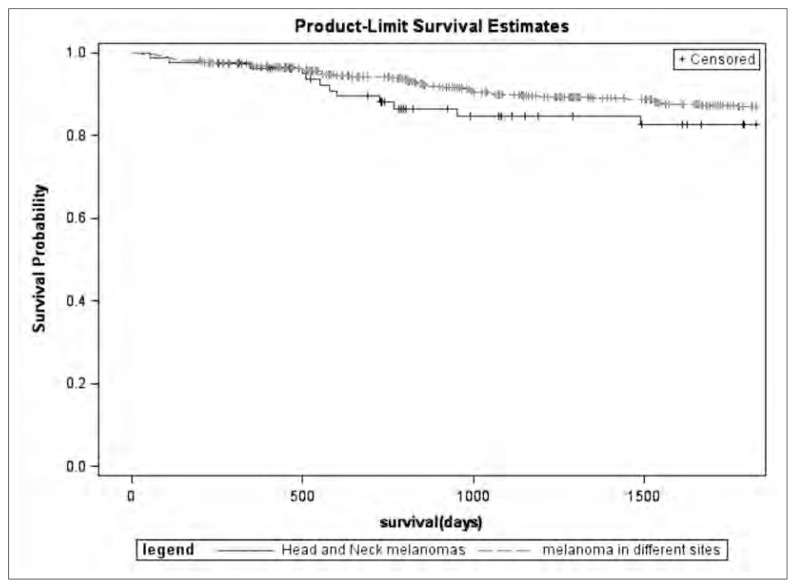

The mean follow-up period amounted to 56.5 months (median duration 46.4, range 1.2–179.6), 12 patients were lost to follow-up. Recurrence-free period (Figure 1) and survival rate (Figure 2) at 5 years were analyzed in HNM cohort and compared with OMS patients. Recurrence-free period and survival rate at 5 years were also analyzed in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model corrected by age, gender, Breslow thickness, presence of ulceration, and presence of positive SLN (Table 2). Patients with HNM showed a worst prognosis than subjects affected by melanomas of different sites, also when the results were corrected for clinical-demographical variables.

Fig. 1.

Recurrence-free period at 5 years in HNM cohort compared with OMS patients.

Fig. 2.

Survival Rate at 5 years in HNM compared with OMS patients.

Table 2.

COX HAZARD RATIO ON 5-YEAR MORTALITY AND RECURRENCE CORRECTED FOR CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND MELANOMA PROGNOSTIC FACTORS.

| 5 years survival | 5 years recurrence-free | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HR | IC 95% | HR | IC 95% | |

| Patients with OMSs | 1.000 | 0.771 | 1.000 | 0.962 |

|

| ||||

| HNM patients | 1.486 | 2.861 | 1.661 | 2.866 |

| 1.827 | 1.887 | |||

|

| ||||

| Positive SLN | 2.972 | 4.835 | 3.013 | 4.810 |

| 1.117 | 0.710 | |||

|

| ||||

| Ulceration | 1.979 | 3.506 | 1.204 | 2.041 |

| 1.066 | 0.713 | |||

|

| ||||

| Breslow ≥ 2 mm | 1.964 | 3.620 | 1.222 | 2.095 |

| 1.008 | 0.984 | |||

|

| ||||

| Age | 1.025 | 1.042 | 0.998 | 1.011 |

| 0.660 | 0.796 | |||

|

| ||||

| Gender (M) | 1.539 | 3.590 | 1.249 | 1.959 |

Discussion

Sentinel lymph node biopsy for head and neck melanomas has been for a long time contested due to the complex lymphatic anatomy of this region and to the frequent complications related to possible injury of neurovascular structures that in this area are strictly connected to lymphatics. Head and neck lymphatic system consists of over 300 lymph nodes often small and closely packed with a usual discordance between clinically predicted lymphatic drainage pathways and those identified by lymphoscintigraphy (10).

In addition to this, the possibility of localization of the sentinel lymph node in the parotid gland, with the risk of injury of the facial nerve, have made SLNB for head and neck melanomas, a questionable choice.

Pan and co-workers (20, 21), however, have shed light on many aspects of the complex head and neck lymphatic anatomy and recent literature (30) begins to agree with SLNB for head and neck melanomas.

Our experience, that is oriented in this direction, showed that the identification of sentinel lymph node in this region was possible in 98.25 % of cases, with a positivity of 26.31% (15/57), similar to OMS cohort. This allowed us to exclude the 74.69% of patients from unnecessary lymph node dissection, reducing hospitalization time, surgical risks and morbidity of patients affected by HNM.

Another important aspect in our data is that contemporary primary excision and SLNB was performed in 5 cases (8.78%) of HNM patients. The choice of a single surgical time is justified by several advantages. First of all an excision before SLNB procedure causes an alteration of anatomical planes, due to the limited distance between the primary lesion and the sentinel node, which makes it difficult to identify and isolate. Secondly reconstructive surgery often requires transposition flaps that modify the course of the lymphatic.

Our studied population showed cases in which the sentinel node wasn’t located in the predicted lymph node basin and lymphoscintigraphy allowed to identify the real sentinel lymph node localized between primary lesion and usual lymph node chain. These unusual lymph nodes (Interval Nodes) were found in 15 cases (26.3%) of HNM, a higher frequency if compared with the 38 (6.4%) cases in the OMS group (31, 32).

Currently, no neurovascular complications have been reported because we made use of magnifiers (loupes) and electrostimulators, when needed.

Our data confirm that the disease-free-period and the over-survival of HNM cohort was significantly shorter than OMS one. Regarding prognosis, in fact, the HNM group counted 17 deaths and 11 patients alive with disease (AWD) at the end of follow-up period, with mortality (20.24%) and a recurrence (33.33%) rates significantly higher respect to the OMS group (13.93% and 25.33% respectively). This can be justified by the clinical findings described by Wallace et al. in 1964 (33) and confirmed by Pan’s studies (20, 21) that showed the presence of a lymphatic- venous anastomoses network of the superficial occipital lymph nodes (two vessels emerged to communicate with a superficial occipital vein in the subcutaneous layer). It should be noted, therefore, that this anastomosis may provide a systemic route for metastatic disease and this would explain the worse prognosis of head and neck melanomas and in particular of scalp melanomas (34).

Conclusion

More accurate knowledge of the complex head and neck lymphatic anatomy, further improvement of lymphoscintigraphy technique, and a high “learning phase” is carrying the search of sentinel lymph node as the “gold standard” procedure for the staging of melanoma also in the head and neck district. The particular and difficult anatomy of this region requires the procedure to be conducted in referral centers, by a multidisciplinary team specifically trained so as to improve the prognosis and to avoid complications in the surgical treatment of patients affected by HNMs.

Footnotes

Best Communication Award at the XXV National Congress of the “Società Polispecialistica Italiana dei Giovani Chirurghi” Bari, 13–15 June 2013

References

- 1.Gomez-Rivera F, Santillan A, McMurphey AB, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in patients with cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck: recurrence and survival study. Head Neck. 2008;30:1284. doi: 10.1002/hed.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doreen M. Agnese, Rebecca Maupin. Head and Neck Melanoma in the Lymph Node Era. Arch Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg. 2007;133(11):1121–1124. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.11.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanon E, Samuel Y, Adler A. Malignant melanoma of the head and neck in children. Review of the literature and report of a case. Archives of Otolaryngology. 1976;102(4):244–247. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1976.00780090086015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garbe C, Buttner P, Bertz J, et al. Primary cutaneous melanoma: prognostic classification of anatomic location. Cancer. 1995;75:2492. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950515)75:10<2492::aid-cncr2820751015>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leong Stanley PL. Role of Selective Sentinel Limph Node Dissection in Head and Neck Melanoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jso.21964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbs P, Robinson WA, Pearlman N, Raben D, Walsh P, Gonzalez R. Management of primary cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck: the University of Colorado experience and a review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2001;77:179. doi: 10.1002/jso.1091. discussion 186e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane WJ, Yugueros P, Clay RP, Woods JE. Treatment outcome for 424 primary cases of clinical stage I cutaneous malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 1997;19:457. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199709)19:6<457::aid-hed1>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, et al. Technical details of intra-operative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127:392. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420040034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leong SP, Accortt NA, Essner R, et al. Impact of sentinel node status and other risk factors on the clinical outcome of head and neck melanoma patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:370. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien CJ, Uren RF, Thompson JF, et al. Prediction of potential metastatic sites in cutaneous head and neck melanoma using lymphoscintigraphy. Am J Surg. 1995;170:461. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leong SP, Achtem TA, Habib FA, et al. Discordance between clinical predictions vs. lymphoscintigraphic and intraoperative mapping of sentinel lymph node drainage of primary melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1472. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.12.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao C, Wong SL, Edwards MJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for head and neck melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:21. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson GW, Page AJ, Cohen C, et al. Regional recurrence after negative sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg. 2008;248:378. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181855718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shashanka R, Smitha BR. Review Article: Head and Neck Melanoma. International Scholarly Research Network. ISRN Surgery. 2012 doi: 10.5402/2012/948302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis AI, Ridge JA. Discordant lymphatic drainage patterns revealed by serial lymphoscintigraphy in cutaneous head and neck malignancies. Head Neck. 2007;29:979. doi: 10.1002/hed.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eberbach MA, Wahl RL, Argenta LC, Froelich J, Niederhuber JE. Utility of lymphoscintigraphy in directing surgical therapy for melanomas of the head, neck, and upper thorax. Surgery. 1987;102:433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herr MW. Skin cancer-melanoma. 2008. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/846566-overview.

- 18.Pathak I, O’Brien CJ, Petersen-Schaeffer K, et al. Do nodal metastases from cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck follow a clinically predictable pattern? Head Neck. 2001;23:785. doi: 10.1002/hed.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parrett BM, Kashani-Sabet M, Singer MI, et al. Long-term prognosis and significance of the sentinel lymph node in head and neckmelanoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:699. doi: 10.1177/0194599812444268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan Wei-Ren, Suami Hiroo, Taylor G Ian. Lymphatic Drainage of the Superficial Tissues of the Head and Neck: Anatomical Study and Clinical Implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31816aa072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan Wei-Ren, Le Roux Cara Michelle. Variation in the Lymphatic Drainage Pattern of the Head and Neck: Further Anatomic Studies and Clinical Implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181fed511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Atkins MB. An evidence-based staging system for cutaneous melanoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(3):131–49. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi CR, De Salvo GL, Trifiro G, Giudice G. The impact of lymphoscintigraphy tecnique on the outcome of sentinel node biopsy in 1313 patients with cutaneous melanoma: an Italian Multicentric Study (SOLISM-IMI) J Nucl Med. 2006;47(2):234–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Testori A, De Salvo GL, Montesco Mc, Giudice G, et al. Clinical consideration on sentinel node biopsy in melanoma from an Italian multicentric study on 1313 patients (SOLISM-IMI) Ann SurgOncol. 2009;16(7):2018–27. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scolyer RA, Murali R, McCarthy SW, Thompson JF. Pathologic examination of sentinel lymph nodes from melanoma patients. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2008;25:100–11. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Akkooi ACJ, De Wilt JHW, Verhoef C, Schmitz PIM, Van Geel AN, Eggermont AMM, Kliffen M. Clinical relevance of melanoma micrometastases (<0,1 mm) in sentinel nodes: are these nodes to be considered negative? Ann of Oncol. 2006;17(10):1578–85. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasquali S, Mocellin S, Mozzillo N, Maurichi M, Quaglino P, Borgognoni L, Solari N, Pizzalunghi D, Mascheroni L, Giudice G, et al. Non-sentinel lymph node status in patients with cutaneous melanoma :results from a multi-institution prognostic study. J Clin Oncology. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.7681. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossi CR, Mozzillo N, Maurichi M, Pasquali S, Macripò G, Borgognoni L, Solari N, Pizzalunghi D, Mascheroni L, Giudice G, et al. The number of excised lymph node as quality assurance measure for lymphadenectomy in melanoma. JAMA surgery. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5676. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi CR, Mozzillo N, Maurichi M, Pasquali S, Quaglino P, Borgognoni L, Solari N, Pizzalunghi D, Mascheroni L, Giudice G, et al. The number of excised lymph node is associated with survival of melanoma patients with lymph node metastasis. Annals of oncology. 2014;25:240–246. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patuzzo R, Maurichi A. Accuracy and prognostic value of sentinel limph node biopsy in head and neck melanomas. Journal of surgical research. 2013;XXX:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uren RF, Howman-Giles R, Thompson JF, McCarthy WH, Quinn MJ, Roberts JM, Shaw HM. Interval nodes: the forgotten sentinel nodes in patients with melanoma. Arch Surg. 2000 Oct;135(10):1168–72. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.10.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giudice G, Asabella AN, Renna MA. Linfonodi sentinella «inu-suali» alla linfoscintigrafia in pazienti con melanoma cutaneo. doi: 10.1701/1315.14581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallace S, Jackson L, Dodd GD, Greening RR. Lymphatic dynamics in certain abnormal states. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1964;91:1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Ow TJ, Myers JN. Pathways for cervical metastasis in malignant neoplasms of the head and neck region. Clinical Anatomy. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ca.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]