Abstract

Objective

The post–traumatic neuro-anastomosis must be protected from the surrounding environment. This barrier must be biologically inert, biodegradable, not compressing but protecting the nerve. Formation of painful neuroma is one of the major issues with neuro-anastomosis; currently there is no consensus on post-repair neuroma prevention. Aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of neuroanastomosis performed with venous sheath to reduce painful neuromas formation, improve the electrical conductivity of the repaired nerve, and reduce the discrepancies of the sectioned nerve stumps.

Patients and methods

From a trauma population of 320 patients treated in a single centre between January 2008 and December 2011, twenty-six patients were identified as having an injury to at least one of the peripheral nerves of the arm and enrolled in the study. Patients were divided into two groups. In the group A (16 patients) the end-to-end nerve suture was wrapped in a vein sheath and compared with the group B (10 patients) in which a simple end-to-end neurorrhaphy was performed. The venous segment used to cover the nerve micro-suture was harvested from the superficial veins of the forearm. The parameters analyzed were: functional recovery of motor nerves, sensitivity and pain.

Results

Average follow-up was 14 months (range: 12–24 months). The group A showed a more rapid motor and sensory recovery and a reduction of the painful symptoms compared to the control group (B).

Conclusions

The Authors demonstrated that, in their experience, the venous sheath provides a valid solution to avoid the dispersion of the nerve fibres, to prevent adherent scars and painful neuromas formation. Moreover it can compensate the different size of two nerve stumps, allowing, thereby, a more rapid functional and sensitive recovery without expensive devices.

Keywords: Painful neuroma, Nerve sprouting, Nerve regeneration

Introduction

Nerve injury can seriously affect quality of life. With nerve damage there can be a wide array of symptoms. Which ones may manifest depends on the location and type of nerves that are affected. Aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of neuro-anastomosis performed with venous sheath to reduce painful neuromas formation, improve the electrical conductivity of the repaired nerve, and reduce the discrepancies of the sectioned nerve stumps.

Patients and methods

Population in study

From January 2008 to December 2012 we treated 320 patients with acute nerve injury. We retrospectively review the data from these patients to compare two different techniques of nerve anastomosis. Exclusion criteria were: periferal nerve injury with a gap >2cm to the arm, metabolic diseases (eg diabetes), age >75, previous injury to the same arm. Inclusion criteria were: periferal nerve injury to the arm, acute injury (whitin 24 hours from the trauma), single injury to each nerve.

Twenty-six patients were selected and the data collected and analyzed. Among them, 16 patients belonging to group “A” (12 male and 4 female, range of age 7–73, mean age 51), were treated with direct end-to-end suture covered by autologous venous wrapping and 10 patients belonging to the group “B” (9 male and 1 female, range of age 11–74, mean age 49) were treated with simple end-to-end neurorrhaphy (Table 1).

Table 1.

POPULATION IN STUDY.

| GROUP A | GROUP B |

|---|---|

| 16 patients | 10 patients |

| End-to-end nerve suture covered with vein segment | Simple end-to-end nerve suture |

The parameters analysed for the processing of the results after a minimum follow-up of 12 months were: functional recovery of motor nerves, sensitivity and pain.

Surgical Technique

The surgical technique consists in the standard identification, isolation and neurolysis of the proximal and distal extremity of peripheral nerve injured, to obtain a good mobilization, and in regularization of the nerve stumps. In the group B we performed an end-to-end neurorrhaphy in the standard fashion.

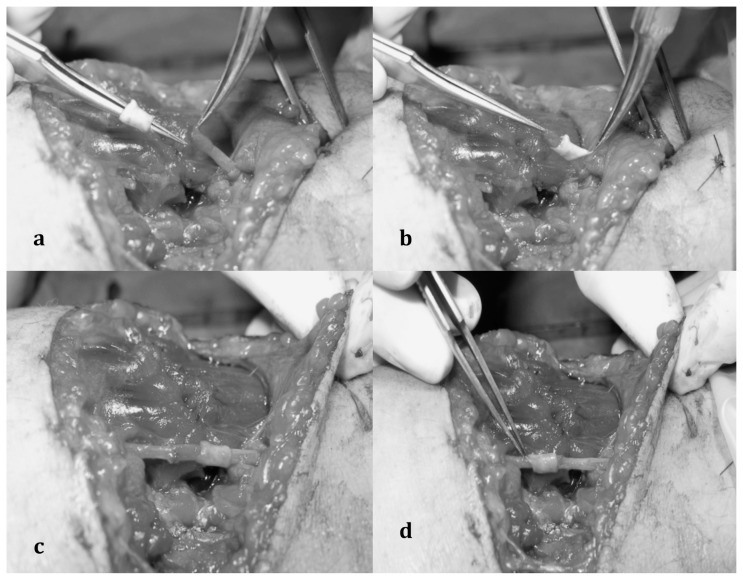

In the group A we harvested the venous segment (2 cm of vein) usually from the superficial venous network of the forearm; the proximal or distal nerve stump is then passed through the venous segment and than a standard end-to-end neurorrhaphy is performed with 9/0 or 8/0 nylon suture. At the end of the procedure the vein segment is transposed to cover the nerve anastomosis (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 a, b, c, d.

a) Dissection of the proximal and distal stump of peripheral nerve injured; b) the proximal nerve stumps is passed through the venous segment; c) end-to-end nerve suture performed; d) nerve suture covered by the venous sheath.

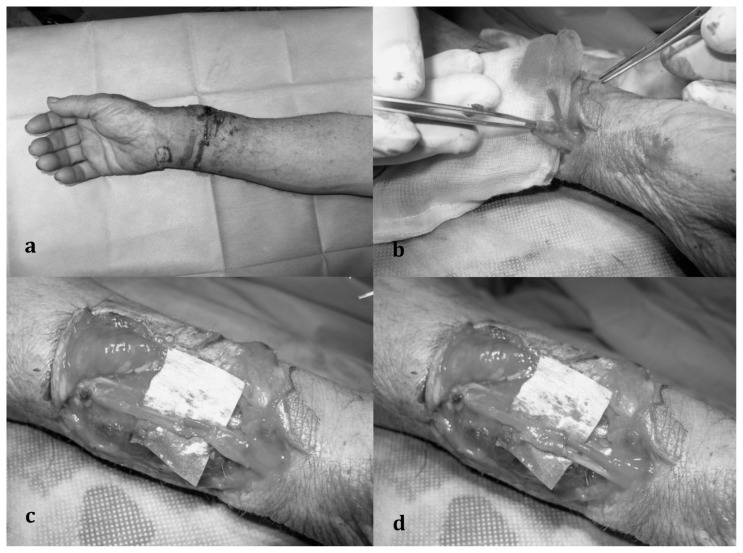

The technique is useful also in case of nerve injury close to a bifurcation as shown in Figure 2. In this case we need to harvest a vein segment with a bifurcation or collateral vein.

Fig. 2 a, b, c, d.

a) Distal forearm laceration with radial nerve injury close to the nerve bifurcation; b) the two nerve stumps pass through the venous sheath, harvested at the level of a vein bifurcation; c) double end-to-end nerve suture; d) wrapping nerve suture “trousers-like”.

Results

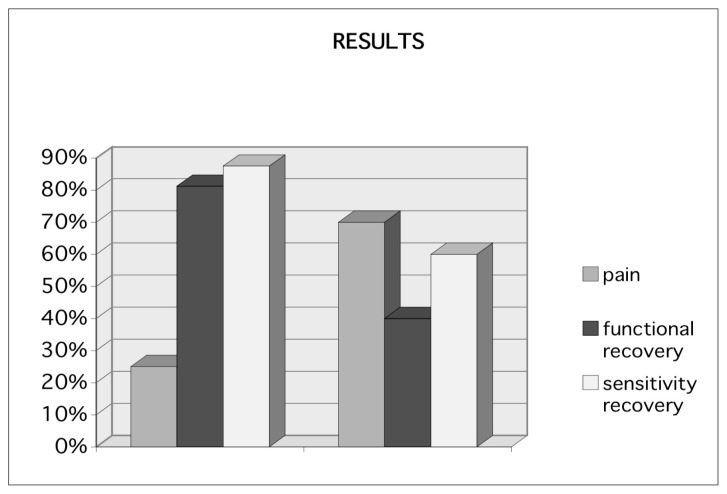

Patients were followed up for a minimum period of 12 months. The group A patients reported pain at the site of neurorrhaphy (positive Tinel sign) in 25% of cases (4 patients) compared to 70% in group B (7 out of 10 patients); functional recovery at 12 months was achieved by the 81,25% of the patients in group A (13 patients), and only in 40% of cases in group B (4 patients), the sensitivity was almost completely recovered in 87,5% of patients in group A (14 patients) and only in 60% of patients in group B (6 patients) (Figures 3 and 4).

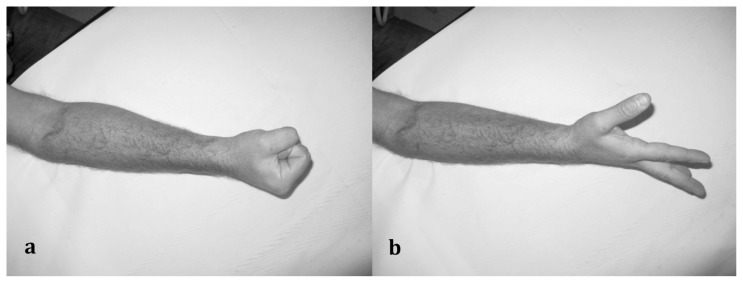

Fig. 3 a, b.

a–b) Functional recovery at 12 months in forearm glass injury with section of the motor branch of Radial nerve. Intraoperative figures are shown in figure 1.

Fig. 4.

Results after 12 months.

Discussion and conclusions

Some studies have reported that more than 60% of peripheral nerve injuries occur in the upper limbs (1, 2). This significant problem requires efficient management in order to avoid disability. The function of the hand is especially dependent on its sensory and motor nerves (1–3). Lorei and Hershman (10) classify neural traumas into chronic injuries or entrapment neuropathies, caused by repetitive trauma or compression, and acute injuries, which is caused by direct trauma leading to immediate onset of symptoms.

Acute injuries are more common in the dominant hand and occur most commonly in young men (1, 4). The most frequently affected nerves are the ulna, radial and digital nerves (1, 2, 5) and the commonest aetiological factors reported are motor vehicle accidents and sharp objects (6).

There is no single classification system that can describe all the many variations of nerve injury. Most systems attempt to correlate the degree of injury with symptoms, pathology and prognosis.

According to Seddon (7) nerve injuries can be referred to as neuropraxia, axonotmesis and neurotmesis according to the disruption of the internal structure and consequently a worsening prognosis. Neuropraxia describes a reversible condition when the electrical signal fails to travel through a nerve segment, when there is no anatomical disruption in the affected neuron. There is minor damage to the axon and the prognosis is better. Axonotmesis consists in a complete interruption of the axon in the affected neuron. Neurotmesis occurs when there is a complete destruction of axons and supporting connective tissue and has the worst prognosis (8).

Sunderland (9) classified acute nerve injuries into five degrees based on severity of the injury. Distal degeneration of neurons following traumatic injury has been termed Wallerian degeneration since Waller (11) described, in 1850, post-traumatic changes in peripheral nerves. It is important to note that endoneurium, the Schwann sheath and blood vessels remain intact despite the occurrence of wallerian degeneration. Proximal changes in the neuron have been termed axonal degeneration.

Severe lesions of the peripheral nerves can result in incomplete axonal regeneration and permanent disability in patients (12). Axonal sprouts form at the proximal stump and grow until they enter the distal stump. The growth of the sprouts is governed by chemotacticfactors secreted from Schwann cells (neurolemmocytes). Injury to the peripheral nervous system immediately elicits the migration of phagocytes, Schwann cells, and macrophages to the lesion site in order to clear away debris such as damaged tissue.

The result of neurorrhaphy depends on the time available before the repair, the patient’s age, type of nerve affected, level of injury, trauma mechanism, but also development of scar fibrosis (13). Fibrosis, in fact, obstruct the growth of axons from the proximal to the distal stump, and can also cause irritation pain syndromes and functional limitations. This phenomenon acts as a trigger for the inflammatory cascade mediated by macrophages, lymphocytes, mast cells, the same Schwann cells, which release neuronal adhesion factors and cytokines. This chain reaction leading to the formation of neuroma (14, 15). Accordingly the reduction of fibrosis should improve the outcome of peripheral nerve suture, but also reduce complications during secondary procedures by facilitating the tissue dissection (16).

Therefore, reconstruction of nerves injuries remains a surgical challenge (17).

The purpose of nerve repair is the precise apposition of the two stumps of injured nerve using a minimum number of sutures with minimal tension. The functional and sensitive recovery is possible only if the motor and sensory fibres of a nerve are correctly connected (18, 19).

For these reasons direct nerve repair, such as epineural or fascicular suturing, can be applied only when there is no gap at the lesion site (primary repair) (20).

Good results were obtained from Vozzi et al. (26) by the use of tubes in poly-caprolactone, a very flexible polymer, already used as a component of absorbable sutures; also Carlucci and Coll. (27) have tried to assess the effects on nerve regeneration of polyurethane, which is used as a polymer forming the guide, and the jelly and Polylysine such as growth factors with which the guides were filled before, so that the tube acts as a veritable chamber of nerve regeneration. Also synthetic tubes are that they are porous which allows the exchange of nutrients and they have biodegradable properties which lower the inflammatory response (28).

In recent years, our surgical approach to traumatic lesions of peripheral nerves has evolved and perfected. Our main objectives are to protect nerve suture from the surrounding environment through the use of biologically inert barrier non-compression, prevent complications and improve nerve conduction.

In our opinion, the only material able to fully meet these goals is represented by a sheath of autologous vein taken from healthy donor area (in most cases from the volar region of the forearm) and used as a cover of the nerve anastomosis.

We used the vein wrapping technique because of its numerous advantages. The first involves facilitating nerve regeneration. The anastomosis site becomes separated from the surrounding tissues, supplying an optimal environment for nerve regeneration. The second advantage relates to the mechanical protection of the anastomosed nerve site. A mechanical chamber could prevent protrusion of fascicles out from the suture line and sprouting axons can be well-aligned within the chamber (28). The third advantage concerns prevention of neuroma formation. To prevent neuroma formation, the vein wrapping technique can be done with the goal of isolating it from the inflammatory cascade and neurotrophic factor production triggered by nerve trauma in the surrounding tissues.

Another important selling point is that veins potentially available for nerve wrapping are easily accessible and available in the same operative field. Veins can be easily dilated with fine surgical forceps to adapt the lumen to the nerve size and can thus be used to treat large nerves. Although successful wrapping with numerous synthetic materials (such as silicon and collagen conduits) has been reported, veins have the advantage of being obtainable at no cost and are easily available. Furthermore, this technique does not cause any risk of venous thrombosis (29). Finally, this technique can be applied in other areas as demonstrated by Young Moon Yoo et Coll. in sections of recurrent laryngeal nerve of patients with thyroid cancer undergoing thyroidectomy with a more rapid recovery of the voice feature (30).

Footnotes

Best Communication Award at the XXV National Congress of the “Società Polispecialistica Italiana dei Giovani Chirurghi”, Bari, 13–15 June 2013

References

- 1.Eser F, Aktekin LA, Bodur H, Atan C. Etiological factors of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries. Neurol India. 2009;57:434–7. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.55614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noble J, Munro CA, Prasad VS, Midha R. Analysis of upper and lower extremity peripheral nerve injuries in a population of patients with multiple injuries. J Trauma. 1998;45:116–22. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199807000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger A, Mailänder P. Advances in peripheral nerve repair in emergency surgery of the hand. World J Surg. 1991;15:493–500. doi: 10.1007/BF01675646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAllister RM, Gilbert SE, Calder JS, Smith PJ. The epidemiology and management of upper limb peripheral nerve injuries in modern practice. J Hand Surg Br. 1996;21:4–13. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(96)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kouyoumdjian JA. Peripheral nerve injuries: a retrospective survey of 456 cases. Muscle Nerve. 2006;34:785–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chimutengwende-Gordon Mukai, Khan Wasim. Recent Advances and Developments in Neural Repair and Regeneration for Hand Surgery. The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 2012 doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seddon HJ. Three types of nerve injury. Brain. 1943;66:237. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosby's medical dictionary. 8th ed. 8. Makti City: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, NY: Churchill and Livingstone; 1978. pp. 69–141. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorei MP, Hershman EB. Peripheral nerve injuries in athletes. Treatment and prevention. Sports Med. 1993;16(2):130–47. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199316020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waller A. Experiments on the section of the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves of the frog, and observations of the alterations produced thereby in the structure of their primitive fibers. Philosoph Trans R Soc Lond (Biol) 1850;140:423. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noble J, Munro CA, Prasad VS, Midha R. Analysis of upper and lower extremity peripheral nerve injuries in a population of patients with multiple injuries. J Trauma. 1998;45(1):116–122. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199807000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adanali G, Verdi M, Tuncel A, et al. Effects of hyaluronic acid-carboxymethylcellulose membrane on extraneural adhesion formation and peripheral nerve regeneration. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2003;19:29–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Görgülü A, Imer M, Simsek O, et al. The effect of aprotinin on extraneural scarring in peripheral nerve surgery: an experimental study. Acta Neurochir [Wien] 1998;140:1303–7. doi: 10.1007/s007010050254. 316 L. Mathieu et al. / Chirurgie de la main 31 (2012) 311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pajardi Giorgio, Cipriani Riccardo, Cozzolino Santolo. Tecniche di microchirurgia vascolare e nervosa nel ratto. Centro di Biotecnologie; Ospedale Cardarelli: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen J, Russel L, Andrus K, et al. Reduction of extraneural scarring by ADCON-T/N after surgical intervention. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:976–84. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199605000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang X, Lim SH, Mao HQ, Chew SY. Current applications and future perspectives of artificial nerve conduits. Exp Neurol. 2010;223(1):86–101. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karol AG. Peripheral nerves and Tendon Transfers. Selected Reading in Plastic Surgery. 2003;9:23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mafi P, Hindocha S, Dhital M, Saleh M. Advances of Peripheral Nerve Repair Techniques to Improve Hand Function: A Systematic Review of Literature. The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 2012;6( Suppl 1: M7):60–68. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolford LM, Stevao EL. Considerations in nerve repair. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2003;16(2):152–156. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2003.11927897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doolabh VB, Hertl MC, Mackinnon SE. The role of conduits in nerve repair: A review. Rev Neurosci. 1996;7(1):47–84. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1996.7.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosaka M. Enhancement of rat peripheral nerve regeneration through artery-including silicone tubing. Exp Neurol. 1990;107(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(90)90064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandt J, Dahlin LB, Lundborg G. Autologous tendons used as grafts for bridging peripheral nerve defects. J Hand Surg Br. 1999;24(3):284–290. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1999.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathieu L, Adam C, Legagneux J, Bruneval P, Masmejean E. Reduction of neural scarring after peripheral nerve suture: An experimental study about collagen membrane and autologous vein wrapping. Chirurgie de la main. 2012;31:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2012.10.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.dos Santos Cunha Armando, Costa Marcio Paulino, Da Silva Ciro Ferreira. Peroneal nerve reconstruction by using glycerol-preserved veins. Histological and functional assessment in rats. Original Article Neurology. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502013000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vozzi G, Carlucci F, Salvadori C, Dini F, Vozzi F, Dominici C, Arispicim, Ciardelli G, Giusti P. L’uso di microguide bioerodibili nella. Nerve Regeneration Atti SICV. 2005;12:213–215. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlucci Fabio, Dini Francesca, Vozzi Giovanni, Vozzi Federico, Chiono Valentina, Salvadori Claudia, Arispici Mario, Domenici Claudio, Ciardelli Gianluca, Giusti Paolo. “The Tunnel Effect” using Bioerodable Tubes in Nerve Regeneration. Annali Fac Med Vet. 2005;Lviii [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaviz Hamdollah, Faghihi Abolfazel, Delshad Alireza Azizzadeh, Bahadori Mohamad hadi, Mohamadi Jamshid, Roozbehi Amrollah. Repair of Peripheral Nerve Defects Using a Polyvinylidene Fluoride Channel Containing Nerve Growth Factor and Collagen Gel in Adult Rats. Cell Journal (Yakhteh) 2011;13(3):137–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubiatowski P, Unsal FM, Nair D, et al. The epineural sleeve technique for nerve graft reconstruction enhances nerve recovery. Microsurgery. 2008;28:160–7. doi: 10.1002/micr.20472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galeano M, Manasseri B, Risitano G, et al. A free vein graft cap influences neuroma formation after nerve transection. Microsurgery. 2009;29:568–72. doi: 10.1002/micr.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoo Young Moon, Il, Lee Jae, Lim Hyoseob, Kim Joo Hyoung, Park Myong Chul. Vein Wrapping Technique for Nerve Reconstruction in Patients with Thyroid Cancer Invading the Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:71–75. doi: 10.5999/aps.2012.39.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]