Abstract

Neurological conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease and stroke, represent a prevalent group of devastating illnesses with few treatments. Each of these diseases or conditions is in part characterized by the dysregulation of many genes, including those that code for microRNAs (miRNAs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). Recently, a complex relationship has been uncovered linking miRNAs and HDACs and their ability to regulate one another. This provides a new avenue for potential therapeutics as the ability to reinstate a careful balance between miRNA and HDACs has lead to improved outcomes in a number of in vitro and in vivo models of neurological conditions. In this review, we will discuss recent findings on the interplay between miRNAs and HDACs and its implications for pathogenesis and treatment of neurological conditions, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease and stroke.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Histone deacetylase, Neurological conditions, Neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

Neurological conditions including stroke, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, are characterized by neuronal cell loss and represent a devastating, prevalent group of diseases, which exact tremendous personal and financial cost on our society. In each condition a diverse set of pathways is engaged leading to neuronal demise. Despite significant efforts, the primary causes for neurodegeneration remain largely unknown likely due to the complexity of the problem. In recent years, miRNAs and histone acetylation have separately garnered significant attention as they are dramatically affected in neurodegenerative diseases. An intriguing relationship has emerged between miRNAs and histone deacetylases (HDACs), which modulate acetylation of histones and other proteins. Indeed, each regulates the other in a variety of contexts in health and disease. This review will focus on the interaction between miRNAs and HDACs and how they impact neurodegenerative diseases. Table 1 provides a summary of the miRNA and HDAC interactions discussed within this review with respect to the each neurological condition.

Table 1.

Summary of known miRNA and HDAC interactions in neurological conditions.

| Disease | miRNA | HDAC | Proposed affects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS | miR-206 | HDAC4 | HDAC4 is negatively regulated by miR-206 HDAC4 prevents reinnervation while miR-206 promotes | Williams et al. (2009) and Bruneteau et al. (2013) |

| HD | miR-22 | HDAC4 and REST | HDAC4 and REST are negatively regulated by miR-22 overexpression of miR-22 is neuroprotective | Jovicic et al. (2013) |

| HD | miR-124 | HDAC1/2 (REST) | miR-124 is down regulated in HD miR-124 negatively regulates REST | Conaco et al. (2006) and Johnson et al. (2008) |

| HD | miR-9/9* | HDAC1/2 (REST and Co-REST) | mir-9 and miR-9* are down regulated in HD miR-9 and miR9* regulate REST and CoREST and in return, REST and CoREST can regulate miR-9 and miR-9*, respectively | Packer et al. (2008) |

| AD/memory | miR-134 miR-124 | SIRT1 | SIRT1 regulates miR-134 Reduced miR-134 results in increased CREB and BDNF as well as improved synaptic plasticity reservatrol enhances SIRT1 activity and reduces miR-134 and miR-124 | Zhao et al. (2013) and Gao et al. (2010) |

| AD | miR-34c | SIRT1 | miR-34c is increased in the hippocampus of AD patients and AD mouse models miR-34c targets SIRT1 and results in memory impairment | Zovoilis et al. (2011) |

| AD | miR-181c miR-9 | SIRT1 | miR-181c and miR-9 are reduced in AD patients and in cells treated with amyloid-beta miR-181c and miR-9 target SIRT1 | Schonrock et al. (2010) and Schonrock and Götz (2012) |

| Ischemic stroke | miR-885-3p miR-331 | HDAC1/2 | miR-885-3p and miR-331 are upregulated in ischemia valproic acid, an HDAC1/2 inhibitor, increases miR-331 and decreases miR-885-3p after ischemia | Hunsberger et al. (2012) |

1.1. MicroRNAs

miRNAs are short (~22 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs, which regulate post-transcriptional gene expression by blocking messenger RNA (mRNA), although they have been shown also to bind directly to RNAs. A number of miRNAs are up or down-regulated in neurological conditions. Of note, some miRNAs have been identified as having protective mechanisms to promote cell viability, while others contribute positively to disease pathogenesis. As nearly half of all known miRNAs have been found in the brain, they have a significant impact on gene expression in the central nervous system (Tardito et al., 2013). The functional roles of many non-coding RNAs, like microRNAs (miRNAs), have only recently been elucidated, which has vastly expanded our understanding of gene regulation. There are currently over 2500 known human miRNAs (from miRBase.org); and each, in turn, have the potential to regulate hundreds of mRNA transcripts (Krek et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2005). Thus, it has been estimated that 50% of mammalian protein-coding genes are regulated by miRNAs (Tardito et al., 2013), making them a major factor in gene regulation. As a result, understanding their mechanisms of action and how they are regulated in the context of diseases of the nervous system is of vital importance.

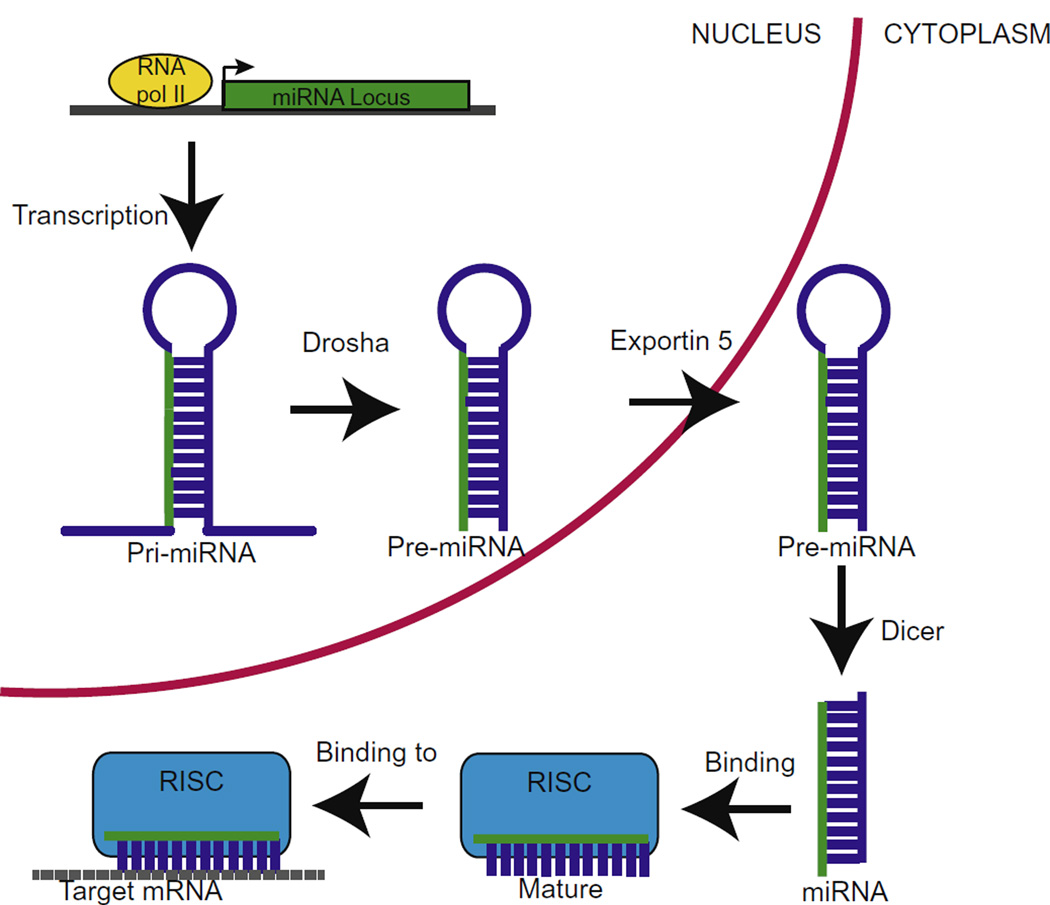

miRNAs are produced through an elaborate but well-documented mechanism, shown in Fig. 1. In the nucleus RNA polymerase II or III is responsible for transcribing primary miRNA (pri-miRNA), which consists of at least one hairpin loop. The pri-miRNA is then excised to form pre-miRNA by the endoribonuclease, Drosha, with the help of DGCR8 (also known as Pasha), a double stranded RNA-binding protein. The ~70 nucleotide pre-miRNA is then exported from the nucleus to the cytosol by Exportin-5 in conjunction with Ran-GTP. In the cytosol, the pre-miRNA undergoes a second endoribonucleic cleavage by Dicer. The resulting double-stranded miRNA combines with an Argonaute (Ago) protein, which determines the complementary strand used to the target mRNA, and the remaining strand is degraded (reviewed in Goodall et al. (2013) and Yates et al. (2013)). While the canonical biogenesis, described above, is the most common method, it should be noted that a non-canonical biogenesis pathway also occurs, which bypasses the Drosha/Dicer processing (Babiarz et al., 2008; Saraiya and Wang, 2008).

Fig. 1.

The canonical miRNA biogenesis pathway. Pri-miRNA is transcribed by RNA polymerase II and excised by Drosha and DGCR8 to from pre-miRNA. Exportin 5 and Ran-GTP then export the pre-miRNA from the nucleus. In the cytoplasm, pre-miRNA is cleaved by Dicer, giving rise to double stranded miRNA, which is then incorporated into RISC and one strand of the miRNA is degraded. Subsquently, the RISC complex binds to target mRNA that is either repressed or degraded.

The single stranded, mature miRNA is then combined into a multi-protein unit, known as miRNA-induced silence complex (miRISC), where it becomes fully functional. The miRNA will then bind to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the target mRNA to prevent further translation (Bartel, 2009). Interestingly, much of the miRNA sequence does not match that of the target mRNA 3′UTR sequence, but a 2–6 nucleotide “seeding” region appears to be critical for recognition and binding of the mRNA (Lewis et al., 2005, 2003). However, there is a direct correlation between the sequence complementarity and the level of gene silencing. A perfect match between miRNA and mRNA will likely lead to degradation of the mRNA; whereas, less homologous sequences will result in transcriptional repression (Goodall et al., 2013).

1.2. Histone acetylation and histone deacetylases (HDACs)

DNA is condensed into chromatin in order to compress an enormous amount of genetic material into a relatively small nucleus. The nucleosome, the basic building block of chromatin, consists of 147 base pairs of DNA that are wrapped around an octamer of histone proteins. The histones can be heavily modified with small molecule post-translational modifications, such as methyl or acetyl groups, which influence the activity and transcription of nearby genes. The pattern of these small molecule post-translational modifications on histones, which govern their interactions with DNA and local propensity for transcription, is commonly referred to as the “histone code.”

Acetylated histones generally are associated with increased transcription. When a histone is acetylated it is thought that the electronegativity of the acetyl group repels the already negatively charged DNA backbone, causing a loosening of the nucleosome and providing space for transcription factors to bind, as shown in Fig. 2. A group of proteins called histone acetyltransferases (HATs), also known as lysine acetyltranserases (KATs), are responsible for the addition of acetyl groups on the lysine residues of the histone tails. This process is undone by HDACs, which remove the acetyl group resulting in transcriptional repression (reviewed in Sleiman et al. (2009)).

Fig. 2.

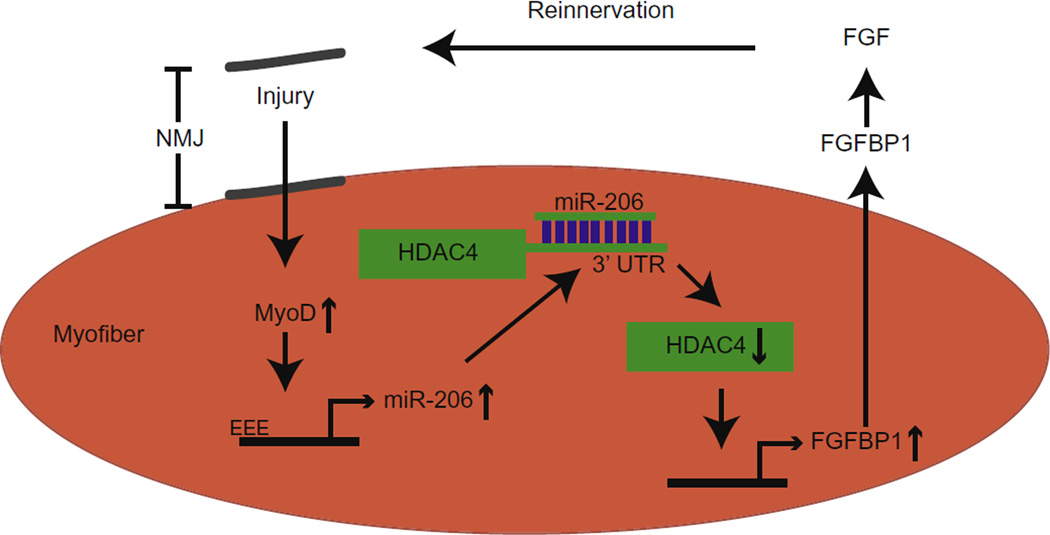

Proposed mechanism of reinnervation. After an injury at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) there is an increase in MyoD, which activates the expression of miR-206. miR-206 binds to the HDAC4 3′UTR, causing a decrease in HDAC4. This in turn leads to an increase in FGFBP1, a secreted growth factor that interacts with FGF and promotes reinnervation. As miR-206 is reduced in ALS, this process is disrupted and prevents reinnervation. Adapted from Williams et al., 2009.

HDACs are divided into four distinct classes based on their structure and cofactors. Classes I (HDACs 1, 2, 3 and 8), II (HDACs 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10) and IV (HDAC 11) are all zinc dependent enzymes, while Class III HDACs, also known as Sirtuins (SIRT 1–7), require NAD+. Available evidence suggests that maintaining histone acetylation in a more active transcriptional state is beneficial to cells, especially during learning, disease or stress situations that require significant plasticity. Accordingly, a tremendous amount of ongoing research investigates the use of HDAC inhibitors to promote the activation of cyto-protective genes and cell survival.

In a number of neurodegenerative diseases, where investigators have looked, histones are notably hypoacetylated. Thus HDAC inhibitors have been used to restore proper histone acetylation and to promote the transcription of neuroprotective and/or neurorestorative genes. Indeed, HDAC inhibitors have been used to ameliorate neurodegeneration. Many HDAC inhibitors initially employed a wide range of HDACs, known as pan inhibitors. However, with the advent of more specific HDAC inhibitors, it is anticipated that we will be able to determine precisely which HDACs should be inhibited to achieve maximum neuroprotection with the fewest side effects.

It also should be noted that while most HDACs primarily act on histone proteins, HDACs are not specific to histone proteins but are also known to deacetylate a number of non-histone proteins. The most common example of this is HDAC6, which resides largely in the cytoplasm where it deacetylates tubulin. However, this review will focus primarily on their histone targets.

1.3. miRNAs and HDACs

miRNAs and HDACs have a complex relationship that is not yet fully understood but could be critically important. miRNAs are capable of regulating HDACs and influencing histone acetylation, while HDACs themselves can regulate miRNA expression. Thus a careful balance between the two is important to maintain appropriate levels of each in the cell. In the case of neurological conditions, the expression of miRNAs and histone acetylation is dramatically affected, which can distort the balance between the two and may contribute to disease pathogenesis. Interestingly, HDAC inhibitors can alter the expression profiles of miRNAs in cancer and in the brain (Scott et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2009), and could become an added benefit of HDAC inhibitors to treat diseases. The ability to control miRNAs and histone acetylation will likely become an important component in managing and treating neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, understanding how they influence each other and affect biological pathways is of significant interest.

2. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects upper and lower motor neurons, resulting in muscle atrophy and paralysis. ALS is typically fatal within 3–5 years of the onset of symptoms. The overwhelming majority of ALS cases are sporadic; but about 10 percent of ALS cases are linked to genetic causes, such as a mutation in the gene that codes for copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) (Valentine et al., 2005). There is currently no cure for the disease and riluzole, the only approved drug for ALS in the United States, is only moderately effective. Early in the disease motor neuron death results in deinnervated neuromuscular junctions (NMJ), which are often reinnervated by the surviving motor neurons (Schaefer et al., 2005; Wohlfart, 1957). Eventually, as more motor neurons die, this compensatory mechanism is unable to sustain the NMJ, resulting in paralysis. This process may explain why most ALS patients remain asymptomatic until the majority of motor neurons have died (Williams et al., 2009).

Many miRNAs are dysregulated in ALS; but one that has received significant attention is miR-206, a skeletal muscle-specific miRNA and associated with the NMJ (Bruneteau et al., 2013; Rao et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2009). Williams et al. showed that miR-206 is significantly increased in a mouse model of ALS expressing an SOD1 mutation (G93A) and is upregulated after acute nerve injury in wild-type mice. While miR-206 knockout mice develop normally, their ability to recover from sciatic nerve injury is greatly diminished. However, in the ALS mouse model the knockout of miR-206 accelerated the atrophy of skeletal muscles, but it did not impact the age of onset or survival (Williams et al., 2009). Therefore, they demonstrated that miR-206 plays a clear role in promoting the regeneration of the neuro-muscular synapse after acute injury and in ALS.

miR-206 was computationally predicted to target HDAC4, and HDAC4 has been strongly implicated in controlling neuromuscular gene expression (Cohen et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2009). Consistent with these studies, Williams et al. found that miR-206 knockout mice had increased HDAC4 protein levels but not HDAC4 mRNA, suggesting the miR-206 regulates HDAC4 via transcriptional repression rather than mRNA destabilization. In contrast to miR-206 knockout mice, mice lacking HDAC4 showed faster muscle reinnervation after injury. Taken together, these results demonstrate the opposing roles of HDAC4 and miR-206 to inhibit and promote reinnervation, respectively in ALS. Furthermore, the same group identified fibroblast growth factor binding protein 1 (FGFBP1) as a common downstream target of both miR-206 and HDAC4. FGFBP1 was downregulated in miR-206 knockout mice but upregulated in HDAC4 knockout mice. As FGFBP1 is known to interact with several fibroblast growth factors that participate in reinnervation, the knockdown of FGFBP1 resembled the miR-206 knockout mice after denervation. The identification of a common downstream target of miRNAs and HDACs, such as FGFBP1, is critical to determining how miRNAs and HDACs influence neurodegenerative diseases and will provide significant insight into disease pathogenesis.

More recently, Brunetau et al. expanded on the elegant work of Williams and colleagues by testing many of these findings in human muscle specimens from ALS patients (Bruneteau et al., 2013). While no change was observed in HDAC4 mRNA between healthy muscles and those from ALS patients, there was an increase in HDAC4 transcript levels in ALS patients with more rapid disease progression than long-term ALS survivors (>5 years survival). This demonstrated a positive correlation between HDAC4 transcript levels and disease progression. They also found that MIR206 and FGFBP1 were significantly upregulated in ALS patients, but no correlation was observed between disease progression or the degree of muscle reinnervation. Thus they were able to validate in human ALS patients that miR-206 is upregulated, likely in an attempt to promote reinnervation, while the inhibitory HDAC4 was downregulated. The relationship between miR-206 and HDAC4 is likely a component of the motor neuron’s coping mechanism to handle the death of other motor neurons. However, this process is ultimately unsuccessful in maintaining the NMJ in advanced stages of ALS.

Given the negative effect of HDAC4 on muscle reinnervation, it has been suggested that HDAC inhibitors could be good drug candidates in slowing the progression of ALS. Trichostatin A, a Class I and II HDAC inhibitor, was recently tested in an ALS mouse model with promising results. Not only was the disease progression delayed, but it also increased the survival of ALS mice. More specifically the number of fully innervated NMJ was increased and muscle atrophy was reduced (Yoo and Ko, 2011). While these results are very promising, the development of HDAC4 specific inhibitors may further improve the outcome of these studies and reduce the numerous side effects associated with non-selective or pan-HDAC inhibitors. Alternatively, one could use infusions of miR-206 as a strategy to reduce HDAC4 and enhance muscle reinnervation.

3. Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder that results in neuronal death specifically in the cerebral cortex and the medium spiny neurons of the striatum. The symptoms of HD include jerky involuntary movements (chorea), dementia and emotional dysfunction. HD is caused by a CAG repeat expansion in the first exon of the gene that codes for the huntingtin protein (Htt) and results in an unusually long and toxic polyglutamine repeat in Htt (MacDonald et al., 1993). Although the cause of HD is attributable to pathological polyglutamine expansions, the mechanism of pathogenesis remains unclear.

Recently, several dysregulated miRNAs have been linked to the pathogenesis of HD. For example,miR-22 is a potentially neuroprotective miRNA that is reduced in HD (Jovicic et al., 2013). It was shown that the overexpression of miR-22 can inhibit neurodegeneration in an in vitro model of HD. miR-22 was computationally predicted to target HDAC4, REST corepressor1 (Rcor1) and G-protein signaling 2 (Rgs2); and, indeed, luciferase-binding assays demonstrated that miR-22 could bind to the mRNA 3′UTR for each of the three predicted targets. miR-22 also targeted MAPK14 and Trp53inp1, which are cell death regulators. Based on these data, it is thought that the anti-apoptotic result of miR-22 overexpression is a combinatorial effect of its downstream targets. As histones are hypoacetylated in HD, blocking HDAC4 translation by increasing miR-22 could promote neuronal survival. It is important to note that the use of HDAC inhibitors, such as SAHA, can ameliorate the symptoms of HD in animal models, making them promising therapeutics in HD (Ferrante et al., 2003; Hockly et al., 2003; Mielcarek et al., 2011; Steffan et al., 2001; Thomas et al., 2008).

Other dysregulated miRNAs in HD are targeted by REST, a master regulator that largely represses neuronal genes in neuronal and non-neuronal cells. REST is known to recruit other co-repressors, notably HDAC1 and HDAC2 to assist in gene silencing. In HD REST appears to play a very complex role between Htt and miRNA transcription. Normal Htt is known to associate with the predominately cytoplasmic REST and, in part, prevents it from entering the nucleus and silencing genes. However, mutant Htt is unable to associate with REST; and, as a result, REST translocates into the nucleus and represses the expression of a number of genes, such as BDNF, other neurotrophic factors, and a number of miRNAs. One such miRNA is miR-124, which is down regulated in HD (Conaco et al., 2006) and subsequently its downstream targets are upregulated (Johnson et al., 2008). miR-124 is a brain specific miRNA that is capable of decreasing non-neuronal transcripts in neurons (Conaco et al., 2006). Based on these results, REST becomes localized to the nucleus in HD, where it silences the production of miR-124, resulting in an increase of non-neuronal gene transcription in neurons. This leads to reduced neuronal-like behavior in neurons, and may subsequently contribute to their degeneration (Lim et al., 2005).

In addition to being regulated by REST, miRNAs, miR-9 and miR-9* can target REST and Co-REST, respectively. Both miR-9 and miR-9* are downregulated in the HD brain so this negative feedback loop becomes dysfunctional and may exacerbate the cascade of genes inappropriately silenced by REST (Packer et al., 2008).

4. Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common age-related neurodegenerative disease, affecting ~2% of the population in industrialized nations. The clinical symptoms of AD include dementia and diminished cognitive functioning, and it is pathologically characterized by the formation of amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. As people live longer, the population suffering from AD is expected to grow dramatically in the next few decades (Abbott, 2011). Without effective therapies to treat AD the social and economic burden of the disease will be immense. As with other neurodegenerative diseases, a number of miRNAs are differentially regulated in AD patients compared with healthy controls.

In AD some of the most affected miRNAs target SIRT1, a class III HDAC, which is known to have a positive effect on learning, memory and longevity (Gao et al., 2010; Howitz et al., 2003; Michán et al., 2010; Wood et al., 2004). SIRT1 can regulate miR-134 through a repressor complex with the transcription factor YY1 (Gao et al., 2010). Loss of SIRT1 leads to an increase in miR-134 and causes a decrease in CREB and BDNF, resulting in impaired synaptic plasticity (Gao et al., 2010). This demonstrates that enhancing SIRT1 may be of therapeutic benefit to neurodegenerative diseases like AD. In a recent study, reservatrol, a natural compound found in grapes and peanuts, was used to enhance SIRT1 activity. In 8–9 month-old mice reservatrol improved long-term memory and improved long-term potentiation in hippocampus CA1 slices (Zhao et al., 2013). The enhancements observed with reservatrol treatment were absent in SIRT1 mutant mice, directly linking the effects of reservatrol to SIRT1 activity. Reservatrol treatment also resulted decreased expression of miR-134 and miR-124. The reduced expression of these miRNAs was then correlated with increased CREB and subsequently increased BDNF (Zhao et al., 2013). Therefore, SIRT1 plays a powerful role in suppressing miR-134 allowing an increase in CREB and BDNF, which could be beneficial in AD.

SIRT1 is also associated with miR-34c, which is upregulated in the hippocampus of AD patients and in the hippocampus of the APPPS1-21 mouse model of AD, as well as in 24 month-old mice. In contrast to miR-134, miR-34c appears to negatively regulate memory consolidation but is also known to target SIRT1 (Yamakuchi et al., 2008; Zovoilis et al., 2011). Consistent with the increase in miR-34c, a decrease in SIRT1 in the hippocampus was observed in 24 month-old mice and the APPPS1-21 mouse model. Mice injected with a miR-34c mimic showed significant memory impairment and decreased SIRT1. Similarly, when APPPS1-21 mice were treated with a miR-34c seed inhibitor, their memory function was rescued to a level similar to that of age-matched controls and was correlated with an increase in SIRT1 (Zovoilis et al., 2011). These data suggest that the dysregulation of miR-34c and the reduced SIRT1 in the hippocampus may contribute to the age-related cognitive decline seen in AD and other dementias.

In AD there is a surprising overlap between the down-regulated miRNAs associated with SIRT1 in AD patients and the presence of amyloidgenic amyloid-beta (Hébert et al., 2008; Schonrock et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2008). Amyloidgenic amyloid-beta is generated from the sequential cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein by beta and gamma secretase, which is thought to predominate in AD patients. However, the preferred non-amyloidgenic pathway utilizes alpha secretase, rather than beta, to produce a slightly shorter amyloid-beta peptide that is not prone to aggregation. miR-9 and miR-181c are both down-regulated in AD patients and in AD models. Both miRNAs were computationally predicted to target the 3′UTR of SIRT1. Indeed luciferase assays showed significant repression of SIRT1 with the addition of miR-9 or miR-181c. Interestingly, when both miR-9 and miR-181c were combined there was an additive effect on the luciferase repression (Schonrock and Götz, 2012). The activation of SIRT1 has previously been shown to delay aging and regulate the aggregation and removal of amyloid-beta (Cohen et al., 2004; Donmez et al., 2010; Qin et al., 2006). In addition, the overexpression SIRT1 is capable of preventing amyloidgenic amyloid-beta by promoting the use of alpha-secretase and the non-amyloidgenic pathway (Qin et al., 2006). Thus, it has been suggested that the repression of miR-9 and miR-181c may result in a neuroprotective increase in SIRT1 to promote non-amyloidgenic amyloid-beta and aid in the clearance of amyloid-beta (Schonrock and Götz, 2012).

5. Stroke

Stroke is a major cause of death and disability, affecting approximately 795,000 people in the US annually. In most cases, a stroke is caused by a loss of blood flow in the brain (ischemic stroke), but it can also be caused by a ruptured blood vessel in the brain (hemorrhagic stroke). Treatment options for either form of stroke remain limited, so there is significant motivation to develop new therapeutic options for stroke treatment. HDAC inhibitors have become potential candidates for the treatment of stroke as they can reverse the hypoacetylation seen after a stroke and can activate the transcription of neuroprotective genes (Chuang et al., 2009; Langley et al., 2009).

A number of miRNAs are differentially regulated after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), an in vivo model of ischemic stroke (Hunsberger et al., 2012; Jeyaseelan et al., 2008). Knowing that HDAC inhibitors can improve the behavioral outcomes in animal models of stroke, and that miRNAs expression can be influenced by HDAC inhibition, Hunsberger et al. measured miRNA profiles after MCAO with and without valproic acid, a Class I HDAC inhibitor. They found that valproic acid treatment reduced the neurological and motor deficits in rats after MCAO and significantly affected the expression of miR-885-3p and miR-331. miR-885-3p was upregulated after MCAO in untreated animals, but this upregulation was attenuated by valproic acid treatment. While relatively little is known about miR-885-3p in the brain, miR-885-3p is upregulated after cisplatin treatment in cancer cells and appears to play a role in cell viability and apoptosis and/or autophagy (Huang et al., 2011). Thus, decreasing miR-885-3p through HDAC inhibition could aid in reducing the cell death after an ischemic stroke and may contribute to the improved behavioral outcomes. In contrast to miR-885-3p, miR-331 was only upregulated after MCAO with valproic acid treatment. It was also upregulated in primary cortical neurons exposed to valproic acid, both preand post-treatment with oxygen-glucose deprivation, an in vitro stroke model. This suggests that miR-331 is directly upregulated by the valproic acid. Based on Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, it is predicted that miR-331 plays a role in cellular movement, cell death, and the organization of the nervous system during development (Hunsberger et al., 2012). In this case, valproic acid had controlled the expression of miRNAs in a neuroprotective manner.

6. Conclusions

In this review we have presented key studies that demonstrate the complex interplay between miRNAs and HDACs in the context of neurodegenerative disease. Their ability to regulate each other provides an intriguing insight into their biological functions in health and disease specific to neurodegenerative processes. However, this field is still in its infancy, and there are a number of challenges that need to be overcome in order to solidify our understanding of how the two components regulate and interact with each other. Perhaps the most important of these is to experimentally confirm many of the computationally determined roles of individual miRNAs. The computational predictions provide excellent insights for experimentalists; and, given the vast number of miRNAs, it is not practical to delve into the mechanistic effects of each miRNA. However, as specific miRNAs are identified as important to a particular disease or biological mechanism, it is imperative to determine the downstream effects of each. Likewise, it is important to further probe the connection between HDACs and miRNAs. One possibility is by using HDAC inhibitors more frequently as a tool to understand how particular classes of HDACs or even individual HDACs affect miRNA expression. This could significantly expand our knowledge of how both miRNAs and HDACs function. While this review focused solely on the effects of HDACs, miRNA expression can influence other chromatin modifications such as DNA and histone methylation. Understanding the functional roles of miRNAs, the effects of HDACs, how they affect each other and how to manipulate their expression could pave the way for new treatment options for neurodegenerative diseases.

References

- Abbott A. Dementia: a problem for our age. Nature. 2011;475:S2–S4. doi: 10.1038/475S2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiarz JE, Ruby JG, Wang Y, Bartel DP, Blelloch R. Mouse ES cells express endogenous shRNAs, siRNAs, and other Microprocessor-independent, Dicer-dependent small RNAs. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2773–2785. doi: 10.1101/gad.1705308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneteau G, Simonet T, Bauché S, Mandjee N, Malfatti E, Girard E, Tanguy M-L, Behin A, Khiami F, Sariali E. Muscle histone deacetylase 4 upregulation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: potential role in reinnervation ability and disease progression. Brain. 2013;136:2359–2368. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang D-M, Leng Y, Marinova Z, Kim H-J, Chiu C-T. Multiple roles of HDAC inhibition in neurodegenerative conditions. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ, Wall NR, Hekking B, Kessler B, Howitz KT, Gorospe M, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;305:390–392. doi: 10.1126/science.1099196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TJ, Waddell DS, Barrientos T, Lu Z, Feng G, Cox GA, Bodine SC, Yao T-P. The histone deacetylase HDAC4 connects neural activity to muscle transcriptional reprogramming. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:33752–33759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaco C, Otto S, Han J-J, Mandel G. Reciprocal actions of REST and a microRNA promote neuronal identity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:2422–2427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511041103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donmez G, Wang D, Cohen DE, Guarente L. SIRT1 suppresses beta-amyloid production by activating the alpha-secretase gene ADAM10. Cell. 2010;142:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Ferrante RJ, Kubilus JK, Lee J, Ryu H, Beesen A, Zucker B, Smith K, Kowall NW, Ratan RR, Luthi-Carter R. Histone deacetylase inhibition by sodium butyrate chemotherapy ameliorates the neurodegenerative phenotype in Huntington’s disease mice. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:9418–9427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09418.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Wang W-Y, Mao Y-W, Gräff J, Guan J-S, Pan L, Mak G, Kim D, Su SC, Tsai L-H. A novel pathway regulates memory and plasticity via SIRT1 and miR-134. Nature. 2010;466:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/nature09271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall EF, Heath PR, Bandmann O, Kirby J, Shaw PJ. Neuronal dark matter: the emerging role of microRNAs in neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;7:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert SS, Horré K, Nicolaï L, Papadopoulou AS, Mandemakers W, Silahtaroglu AN, Kauppinen S, Delacourte A, De Strooper B. Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease correlates with increased BACE1/beta-secretase expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:6415–6420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710263105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockly E, Richon VM, Woodman B, Smith DL, Zhou X, Rosa E, Sathasivam K, Ghazi-Noori S, Mahal A, Lowden PA. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, ameliorates motor deficits in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:2041–2046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, Zipkin RE, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang L-L. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Chuang AY, Ratovitski EA. Phospho-ΔNp63alpha/miR-885-3p axis in tumor cell life and cell death upon cisplatin exposure. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3938–3947. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.22.18107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger JG, Fessler EB, Wang Z, Elkahloun AG, Chuang D-M. Post-insult valproic acid-regulated microRNAs: potential targets for cerebral ischemia. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2012;4:316–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan K, Lim KY, Armugam A. MicroRNA expression in the blood and brain of rats subjected to transient focal ischemia by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2008;39:959–966. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Zuccato C, Belyaev ND, Guest DJ, Cattaneo E, Buckley NJ. A microRNA-based gene dysregulation pathway in Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008;29:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovicic A, Jolissaint JFZ, Moser R, Santos MdFS, Luthi-Carter R. MicroRNA-22 (miR-22) overexpression is neuroprotective via general anti-apoptotic effects and may also target specific huntington, Äôs disease-related mechanisms. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek A, Grün D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley B, Brochier C, Rivieccio MA. Targeting histone deacetylases as a multifaceted approach to treat the diverse outcomes of stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:2899–2905. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Shih I-H, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald ME, Ambrose CM, Duyao MP, Myers RH, Lin C, Srinidhi L, Barnes G, Taylor SA, James M, Groot N. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michán S, Li Y, Chou MMH, Parrella E, Ge H, Long JM, Allard JS, Lewis K, Miller M, Xu W. SIRT1 is essential for normal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:9695–9707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0027-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielcarek M, Benn CL, Franklin SA, Smith DL, Woodman B, Marks PA, Bates GP. SAHA decreases HDAC 2 and 4 levels in vivo and improves molecular phenotypes in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer AN, Xing Y, Harper SQ, Jones L, Davidson BL. The bifunctional microRNA miR-9/miR-9* regulates REST and CoREST and is downregulated in Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:14341–14346. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2390-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin W, Yang T, Ho L, Zhao Z, Wang J, Chen L, Zhao W, Thiyagarajan M, MacGrogan D, Rodgers JT. Neuronal SIRT1 activation as a novel mechanism underlying the prevention of Alzheimer disease amyloid neuropathology by calorie restriction. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:21745–21754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PK, Kumar RM, Farkhondeh M, Baskerville S, Lodish HF. Myogenic factors that regulate expression of muscle-specific microRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:8721–8726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602831103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiya AA, Wang CC. SnoRNA, a novel precursor of microRNA in Giardia lamblia. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000224. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AM, Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. A compensatory subpopulation of motor neurons in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005;490:209–219. doi: 10.1002/cne.20620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonrock N, Götz J. Decoding the non-coding RNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012;69:3543–3559. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonrock N, Ke YD, Humphreys D, Staufenbiel M, Ittner LM, Preiss T, Götz J. Neuronal microRNA deregulation in response to Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott GK, Mattie MD, Berger CE, Benz SC, Benz CC. Rapid alteration of microRNA levels by histone deacetylase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1277–1281. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleiman SF, Basso M, Mahishi L, Kozikowski AP, Donohoe ME, Langley B, Ratan RR. Putting the ’HAT’ back on survival signalling: the promises and challenges of HDAC inhibition in the treatment of neurological conditions. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2009;18:573–584. doi: 10.1517/13543780902810345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffan JS, Bodai L, Pallos J, Poelman M, McCampbell A, Apostol BL, Kazantsev A, Schmidt E, Zhu Y-Z, Greenwald M. Histone deacetylase inhibitors arrest polyglutamine-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Nature. 2001;413:739–743. doi: 10.1038/35099568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Macpherson P, Marvin M, Meadows E, Klein WH, Yang X-J, Goldman D. A histone deacetylase 4/myogenin positive feedback loop coordinates denervation-dependent gene induction and suppression. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1120–1131. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardito D, Mallei A, Popoli M. Lost in translation. New unexplored avenues for neuropsychopharmacology: epigenetics and microRNAs. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2013;22:217–233. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.749237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EA, Coppola G, Desplats PA, Tang B, Soragni E, Burnett R, Gao F, Fitzgerald KM, Borok JF, Herman D. The HDAC inhibitor 4b ameliorates the disease phenotype and transcriptional abnormalities in Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:15564–15569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804249105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JS, Doucette PA, Zittin Potter S. Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:563–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W-X, Rajeev BW, Stromberg AJ, Ren N, Tang G, Huang Q, Rigoutsos I, Nelson PT. The expression of microRNA miR-107 decreases early in Alzheimer’s disease and may accelerate disease progression through regulation of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:1213–1223. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5065-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AH, Valdez G, Moresi V, Qi X, McAnally J, Elliott JL, Bassel-Duby R, Sanes JR, Olson EN. MicroRNA-206 delays ALS progression and promotes regeneration of neuromuscular synapses in mice. Science. 2009;326:1549–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1181046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfart G. Collateral regeneration from residual motor nerve fibers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1957;7:124–124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.7.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430:686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Lowenstein CJ. MiR-34a repression of SIRT1 regulates apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:13421–13426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801613105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates LA, Norbury CJ, Gilbert RJ. The long and short of MicroRNA. Cell. 2013;153:516–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo Y-E, Ko C-P. Treatment with trichostatin A initiated after disease onset delays disease progression and increases survival in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 2011;231:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YN, Li WF, Li F, Zhang Z, Dai YD, Xu AL, Qi C, Gao JM, Gao J. Resveratrol improves learning and memory in normally aged mice through microRNA-CREB pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Yuan P, Wang Y, Hunsberger JG, Elkahloun A, Wei Y, Damschroder-Williams P, Du J, Chen G, Manji HK. Evidence for selective microRNAs and their effectors as common long-term targets for the actions of mood stabilizers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1395–1405. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zovoilis A, Agbemenyah HY, Agis-Balboa RC, Stilling RM, Edbauer D, Rao P, Farinelli L, Delalle I, Schmitt A, Falkai P. MicroRNA-34c is a novel target to treat dementias. EMBO J. 2011;30:4299–4308. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]