Abstract

The crystal structure of the human mitochondrial RNA polymerase (mtRNAP) transcription elongation complex was determined at 2.65 Å resolution. The structure reveals a 9–base pair hybrid formed between the DNA template and the RNA transcript and one turn of DNA both upstream and downstream of the hybrid. Comparisons with the distantly related RNAP from bacteriophage T7 indicates conserved mechanisms for substrate binding and nucleotide incorporation, but also strong mechanistic differences. Whereas T7 RNAP refolds during the transition from initiation to elongation, mtRNAP adopts an intermediary conformation that is capable of elongation without refolding. The intercalating hairpin that melts DNA during T7 RNAP initiation separates RNA from DNA during mtRNAP elongation. Newly synthesized RNA exits towards the PPR domain, a unique feature of mtRNAP with conserved RNA recognition motifs.

INTRODUCTION

The genome of mitochondria is transcribed by a single-subunit RNAP that is distantly related to the RNAP of bacteriophage T7 (refs. 1–4). The structure of human mtRNAP revealed a unique pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) domain, a N-terminal domain (NTD) that resembles the promoter-binding domain of T7 RNAP, and a C-terminal catalytic domain (CTD) that is conserved in T7 RNAP3,5. The CTD adopts the canonical right hand fold of polymerases of the polA family, and its subdomains thumb, palm, and fingers flank the active center3,5.

The free mtRNAP structure adopts an inactive ‘clenched’ conformation with a partially closed active center, and therefore provides limited functional insights5. The structure reveals two loops in the NTD that correspond to functional elements in T7 RNAP, the AT-rich recognition loop and the intercalating hairpin6–8. The AT-rich recognition loop binds promoter DNA during initiation of T7 RNAP, but is sequestered by the PPR domain in mtRNAP and is not required for mtRNAP initiation5. The intercalating hairpin melts DNA during transcription initiation by T7 RNAP, but is repositioned far away from the nucleic acids upon the transition from initiation to elongation when the NTD refolds6–8. It is unknown whether a similar refolding of the NTD occurs in mtRNAP and what the function of the intercalating hairpin is during mitochondrial transcription.

Although mtRNAP was studied more extensively in recent years, detailed mechanistic insights into the mitochondrial transcription cycle are lacking. To gain insights into the elongation phase of mitochondrial transcription, we used a combination of X-ray crystallography, transcription assays, and cross-linking experiments. Here we report the crystal structure of the functional mtRNAP elongation complex with DNA template and RNA transcript. Together with biochemical data, the structure elucidates the elongation mechanism of mtRNAP and reveals striking differences to the T7 transcription system with respect to the transition from initiation to elongation.

RESULTS

Structure of mtRNAP elongation complex

We co-crystallized human mtRNAP (residues 151–1230, Δ150 mtRNAP) with a nucleic acid scaffold that contained a 28–mer DNA duplex with a mismatched ‘bubble’ region and a 14–mer RNA with nine nucleotides that were complementary to the template strand in the bubble (Fig. 1a and Methods). The reconstituted elongation complex was active in a primer extension assay (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). We solved the structure by molecular replacement and refined it to a free R-factor of 22% at 2.65 Å resolution (Table 1).

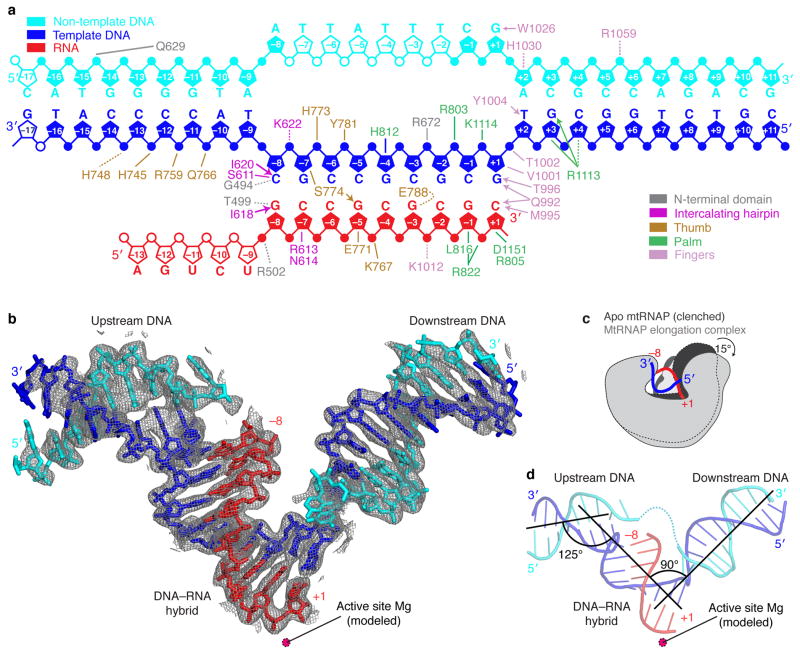

Figure 1. Nucleic acid structure and mtRNAP interactions observed in the crystal structure.

(a) Schematic overview of interactions between mtRNAP and nucleic acids. The nucleic acid scaffold contains template DNA (blue), non-template DNA (cyan) and RNA (red). Unfilled elements were not visible in the electron density map. Interactions with mtRNAP residues are indicated as lines (hydrogen bonds, ≤3.6 Å), dashed lines (electrostatic contacts, 3.6–4.2 Å), or arrows (stacking interactions).

(b) Refined nucleic acid structure with 2Fo-Fc electron density omit map contoured at 1.5σ.

(c) Polymerase opening from the clenched conformation of free mtRNAP (PDB 3SPA5, dark grey) to the elongation complex (light grey). Structures were superimposed based on their NTDs.

(d) Angles between duplex axes of upstream DNA, DNA–RNA hybrid, and downstream DNA.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics (molecular replacement).

| mtRNAP elongation complex | |

|---|---|

| Data collectiona | |

| Space group | I23 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a=b=c (Å) | 225.2 |

| Resolution (Å) | 39.8–2.65 (2.72–2.65)b |

| Rsym (%) | 12 (229) |

| I/σI | 18.9 (1.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Redundancy | 20.7 (20.2) |

| CC (1/2)c (%) | 100 (42.5) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 39.81–2.65 |

| No. reflections | 54985 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 17.3/20.8 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 7880 |

| Ligand/ion | 1265 |

| Water | 244 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 94.4 |

| Ligand/ion | 138.1 |

| Water | 83.5 |

| r.m.s deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.24 |

The structure reveals a new mtRNAP conformation, most of the DNA and RNA, and details of the polymerase-nucleic acid contacts (Figs. 1 and 2). The protein structure includes the previously mobile part of the thumb (residues 736–769), and only lacks two disordered loops, the terminal tip of the intercalating hairpin (residues 595–597), and a loop called specificity loop in T7 RNAP (residues 1086–1106). Compared to the clenched conformation of the free polymerase5, the active center is widened by rotations of the palm and fingers by 10° and 15°, respectively, and neatly accommodates a 9–base pair DNA-RNA hybrid (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Video 1 online).

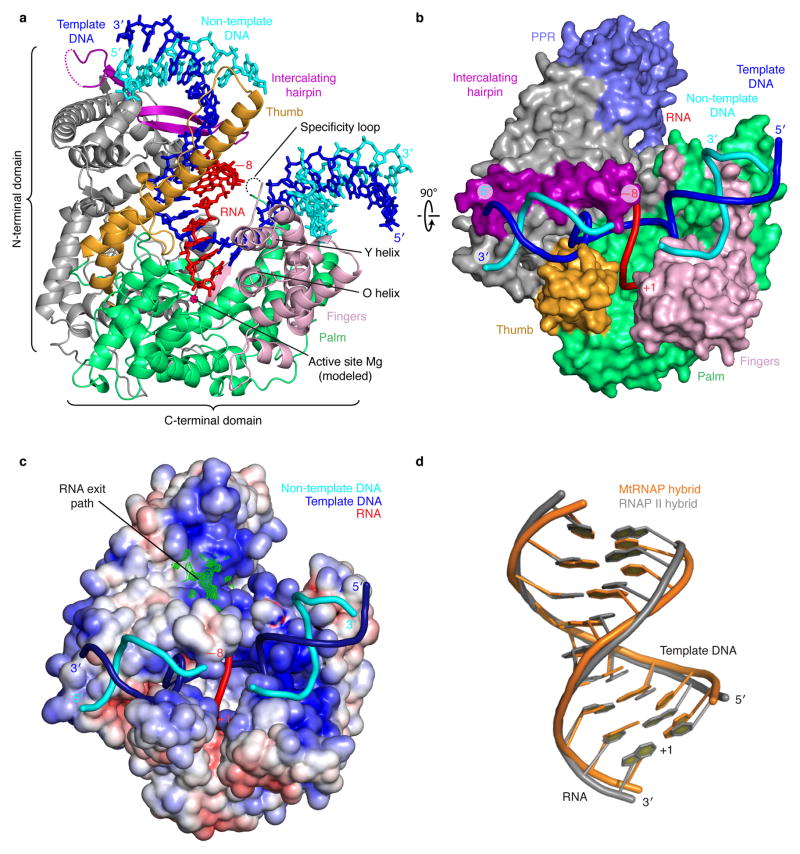

Figure 2. Structure of mtRNAP elongation complex determined by x-ray crystallography.

(a) Overview with mtRNAP depicted as a ribbon (thumb, orange; palm, green; fingers, pink; intercalating hairpin, purple), and nucleic acids as sticks (color code as in Fig. 1). A Mg2+ ion (magenta) was placed according to a T7 RNAP structure9. PPR domain was omitted for clarity.

(b) View of the structure rotated by 90° around a horizontal axis. The polymerase is depicted as a surface model and includes the PPR domain (slate). Nucleic acids are depicted as ribbons.

(c) Electrostatic surface representation of the mtRNAP elongation complex with template DNA (blue), non-template DNA (cyan) and RNA (red). The Fo-Fc electron density of the mobile 5′-RNA tail is shown as a green mesh (contoured at 2.5 σ).

(d) Superimposition of RNA–DNA hybrids in elongation complexes of mtRNAP (orange) and RNAP II (PDB 1I6H33, grey).

Substrate selection and catalysis

The active site closely resembles that of T7 RNAP and harbors the RNA 3′-end at its catalytic residue D1151 (refs. 6–8) (Fig. 3a). Comparison with phage RNAP structures that contain the nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) substrate9,10 supports a conserved mechanism of substrate binding, selection, and catalysis. The location and relative arrangement of amino acid residues in the active center that bind catalytic metal ions and the NTP substrate are conserved in both enzymes. The trajectory of several side chains differs, but this was likely due to the absence of metal ions and NTP in our structure.

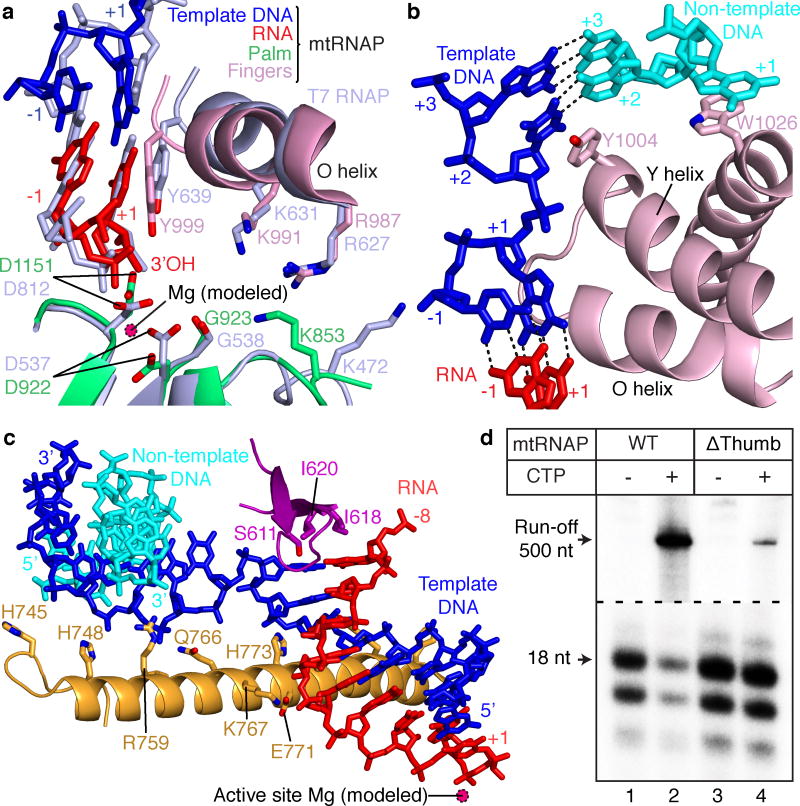

Figure 3. Active center and nucleic acid strand separation observed in the crystal structure.

(a) Conservation of active centers in mtRNAP (color code as in Figs. 1 and 2) and T7 RNAP (PDB 3E2E15, light blue). Structures were superimposed based on their palm subdomains and selected residues were depicted as stick models.

(b) Downstream DNA strand separation.

(c) RNA separation from DNA at the upstream end of the hybrid and thumb–hybrid interactions.

(d) Primer extension assays showed that a thumb subdomain plays a key role in elongation complex stability. Elongation complexes of WT (lanes 1 and 2) and Δthumb (lanes 3 and 4) mtRNAP variants were halted 18 nucleotides (nts) downstream of the light-strand promoter (LSP) by omitting cytidine triphosphate (CTP)31 (see also Supplementary Fig. 5a online).

In the mtRNAP elongation complex, the 3′-terminal RNA nucleotide occupies the NTP site and is paired with the DNA template base +1 (Fig. 3a). Thus the complex adopts the pre-translocation state7,9, and this may be why we could not obtain a structure with NTP. Modeling suggested that translocation enables binding of the NTP between residues K853, R987 and K991 on one side and two metal ions coordinated by residues G923, D922 and D1151 on the other side (Fig. 3a). The NTP 2′-OH group may contact residue Y999 (Fig. 3a). This contact likely helps to discriminate NTP from deoxy-NTP substrates, as revealed by extensive biochemical11,12 and structural studies6.

Polymerase-nucleic acid interactions

The active center is complementary to the hybrid duplex, which adopts A-form (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 1 online), and could not accommodate a B-form duplex that would result from erroneous DNA synthesis. The DNA–RNA hybrid forms many contacts with the polymerase, including contacts to the thumb (Figs. 1a, 2a and 3c). Movement of the thumb was previously detected during different stages of the nucleotide addition cycle, implicating this domain in elongation complex stability, processivity, and translocation in the pol A family of polymerases13,14.

To test the functional role of the thumb domain, we carried out in vitro transcription assays. Deletion of thumb residues 734–773 in human mtRNAP did not result in any significant processivity defects, but we observed a markedly decreased stability of the elongation complex in salt-dependent primer extension assays (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b online). When we halted an elongation complex formed with the thumb deletion (Δthumb) mutant by withholding the substrate NTP, the polymerase was unable to resume elongation and dissociated during run-off transcription assays (Fig. 3d), suggesting a key role of thumb–hybrid interactions in maintaining complex stability during elongation.

We resolved both downstream and upstream DNA in our structure. These DNA elements formed B-form duplexes near positively charged surfaces of the polymerase NTD and CTD, respectively (Fig. 2c). The downstream DNA runs perpendicular to the hybrid (Fig. 1d), as observed in elongation complex structures of T7 RNAP7,9,15–17 and the unrelated multi-subunit RNAP II (refs. 18,19). Thus a 90° bend between downstream and hybrid duplexes is apparently a general feature of transcribing enzymes. The length and conformation of the hybrid are also very similar and apparently dictated by intrinsic nucleic acid properties (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 1 online). The axes of upstream DNA and the hybrid encloses a 125° angle (Fig. 1d).

DNA strand separation

As the polymerase advances, the strands of downstream DNA must be separated before the active site. The structure showed that DNA strand separation involves the fingers domain (Fig. 3b). The side chain of tryptophane W1026 stacks onto the +1 base of the non-template DNA, directing it away from the template strand (Fig. 3b). The side chain of tyrosine Y1004 in the Y helix stacks onto the +2 DNA template base, stabilizing a 90° twist of the +1 template base and allowing its insertion into the active center (Fig. 3b). This is achieved by a 25° rotation of the Y helix compared to its position in free mtRNAP5. Whereas residue Y1004 has a structural counterpart in T7 RNAP, residue F644 (refs. 4,9,16,17), residue W1026 does not (Supplementary Fig. 3 online), suggesting that the mechanisms of strand separation are likely conserved between the two polymerases.

RNA separation and exit

At the upstream end of the hybrid, RNA is separated from the DNA template by the intercalating hairpin, which protrudes from the NTD (Figs. 2a and 3c). The hairpin stacks with its exposed isoleucine residues I618 and I620 onto RNA and DNA bases, respectively, of the last hybrid base pair at the upstream position –8. Consistent with the role of the intercalating hairpin during elongation, elongation complexes assembled with the intercalating hairpin deletion, RNA extension assays revealed that variants of mtRNAP were considerably less stable than complexes with wild-type20 mtRNAP (Supplementary Fig. 2c online). This is in contrast to T7 RNAP13, where the intercalating hairpin is not important for RNA displacement and transcription bubble stability during elongation.

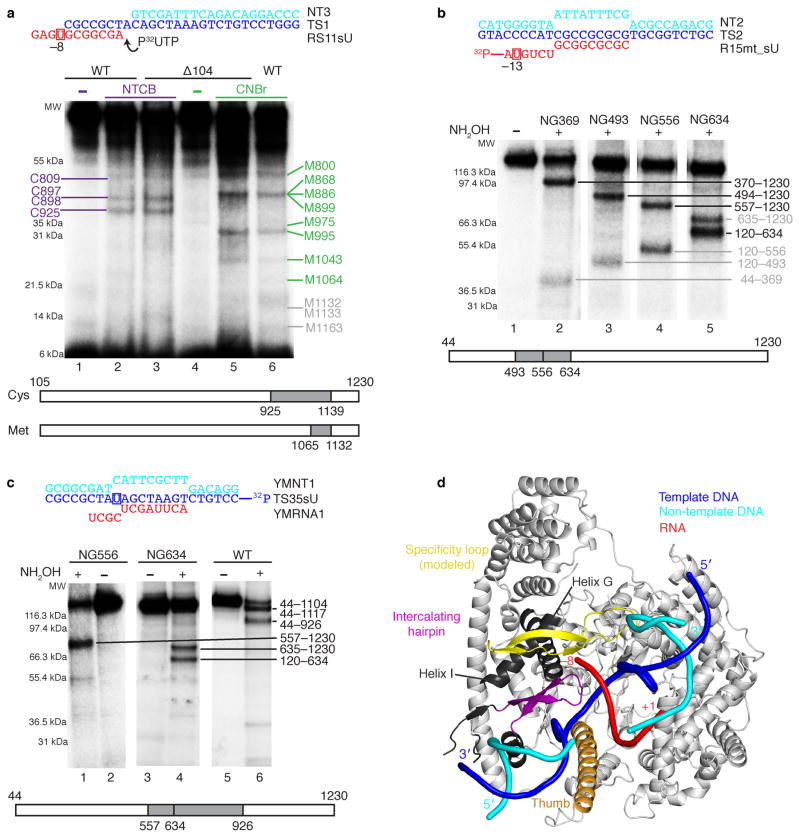

RNA exits over a positively charged surface patch, but shows poor electron density that indicates mobility (Fig. 2d). To investigate whether the weak electron density reflects the RNA exit path, we carried out protein–RNA cross-linking experiments. When we replaced the first RNA base beyond the hybrid by a photo cross-linkable analogue, it was cross-linked to the specificity loop (Figs. 4a, d and Supplementary Fig. 4 online). Thus the mobile specificity loop lines the RNA exit channel, as in the T7 RNAP elongation complex16,17. Exiting RNA at position –13 cross-linked to NTD helices I and G and thus the transcript emerges towards the PPR domain (Figs. 4b, d) that contains conserved RNA recognition motifs21.

Figure 4. Analysis of mtRNAP–nucleic acid contacts by cross-linking experiments (see also Supplementary Fig. 5b and c online).

(a) RNA nucleotide –9 cross-links to the specificity loop of mtRNAP. The cross-linked complexes were treated with 2-nitro-5-thiocyano-benzoic acid (NTCB, lanes 2 and 3) or cyanogen bromide (CNBr, lanes 5 and 6). Positions of the cysteine (cys) and methionine (met) residues that produced labeled peptides are indicated in purple and green, correspondingly. Grey numbers indicate methionine residues that did not produce labeled peptides and the expected migration of these peptides.

(b) Mapping of the RNA–mtRNAP cross-link at RNA nucleotide –13 with different mtRNAP variants having a single hydroxylamin clevage site (NG) at a defined position. The cross-links were treated with hydroxylamine (NH2OH). The major cross-linked peptides are highlighted in black, minor (less than 10%) cross-linking sites in grey.

(c) Mapping of the template strand DNA–mtRNAP cross-link at nucleotide –8. The cross-links were treated with NH2OH as described above.

(d) Location of the cross-linked regions in mtRNAP elongation complex.

The T7 RNAP specificity loop was built into the mRNAP structure by homology modeling. The structural elements that belong to the identified cross-linked regions and lie within 3–5 Å from the photo cross-linking probe include the modeled specificity loop (yellow, residues 1080–1108), part of the thumb (orange, residues 752–791) and part of the intercalating hairpin (purple, residues 605–623). Cross-linked regions that are not part of a defined structural element are shown in dark grey (e.g. helix G residues 587–571 and helix I residues 570–586).

Lack of NTD refolding upon elongation

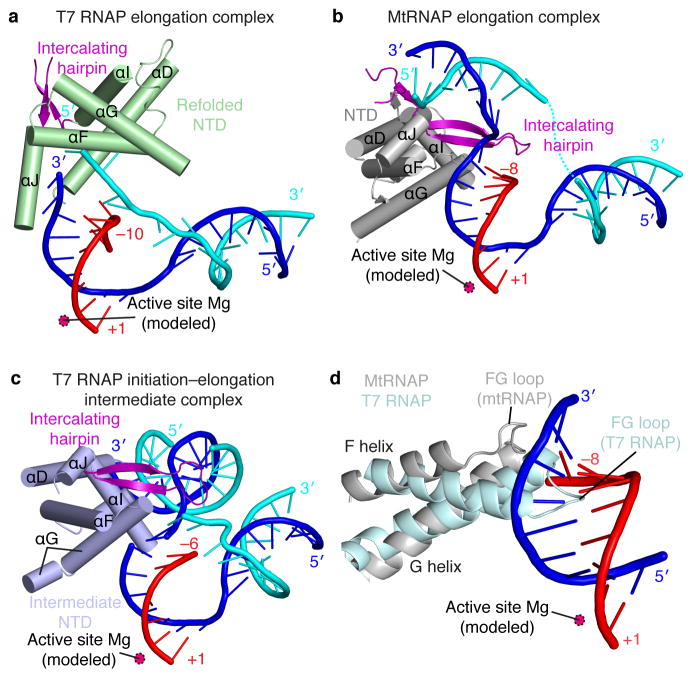

To initiate transcription, T7 RNAP binds promoter DNA with its NTD7,22. The NTD then refolds during the transition from an initiation complex4 to an elongation complex16 via an intermediary state15. In contrast, the NTD of mtRNAP does not refold during the initiation–elongation transition (Fig. 5). The NTD fold observed in our mtRNAP elongation complex structure differs from that in T7 RNAP elongation complexes, but resembles that in the T7 initiation–elongation intermediate, and is partially related to that in the T7 initiation complex (Figs. 5a–c and Supplementary Table 2 online).

Figure 5. Lack of NTD refolding upon mtRNAP elongation observed in the crystal structure.

(a–c) Structures of the NTDs of T7 RNAP and mtRNAP. The NTD of T7 RNAP (a) is refolded in the elongation complex (PDB 1MSW34), whereas the NTD of mtRNAP (b) is not, and resembles the NTD in the T7 intermediate (PDB 3E2E15) (c). Helices are depicted as cylinders and nucleic acids as ribbons with sticks for protruding bases.

(d) The FG loop of T7 RNAP (PDB 1QLN4, pale cyan) protrudes into the hybrid-binding site but is shorter and positioned differently in mtRNAP (silver).

Our crystallized mtRNAP complex represents an elongation complex rather than an intermediate of the initiation–elongation transition because it shows full RNA-extension activity and comprises a mature 9–base pair DNA–RNA hybrid with a free 5′-RNA extension exiting the polymerase (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Consistent with a lack of NTD refolding, the DNA template position –8 in the elongation complex could be cross-linked to a region that encompasses the intercalating hairpin5,23 (Figs. 4c, d). In striking contrast, NTD refolding in T7 RNAP moves the intercalating hairpin more than 40 Å away from the hybrid upon elongation (Figs. 5a–c).

DISCUSSION

Transcription of the mitochondrial genome is essential for all eukaryotic cells, yet its mechanisms remain poorly understood. Thus far only the structure of free mtRNAP was reported, whereas structures of functional mtRNAP complexes were lacking. Here we present the structure of a functional mtRNAP complex, that of the human mtRNAP elongation complex. The structure showed that nucleic acid binding leads to an opening of the polymerase active center cleft, and an ordering of the thumb domain and most of the intercalating hairpin. The structure revealed the arrangement of downstream and upstream DNA on the polymerase surface, and the DNA–RNA hybrid in the active center, as well as detailed nucleic acid–polymerase contacts.

The structure of the mtRNAP elongation complex also enabled a detailed comparison with the distantly related RNAP from bacteriophage T7. This indicated conserved mechanisms for substrate selection and binding, and for catalytic nucleotide incorporation into growing RNA. Downstream DNA strand separation is achieved by the fingers domain and at least partially resembles strand separation by T7 RNAP. Taken together, the polymerase CTD and mechanisms that rely on this domain were largely conserved during evolution of single-subunit RNAPs24.

Our results also revealed striking mechanistic differences between T7 RNAP and mtRNAP. In particular, the NTD does not refold during the transition from transcription initiation to elongation. In T7 RNAP4,15, NTD refolding is triggered by a clash of the growing DNA–RNA hybrid with residues 127–133 in the FG loop. In contrast, this loop is two residues shorter in mtRNAP and positioned such that it allows for hybrid growth without NTD refolding (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 3 online).

We suggest that during evolution of mtRNAP from an early bacteriophage-like RNAP the catalytic CTD and elongation mechanism remained highly conserved, whereas the NTD lost its capacity to adopt an initiation-specific fold with functions in promoter binding and opening, as initiation factors became available to take over these functions. A loss of NTD refolding and its intrinsic initiation functions in mtRNAP apparently went along with the evolution of initiation factors TFAM and TFB2M3,8,25,26, which are responsible for promoter binding27–29 and opening30,31, respectively.

As a consequence, mtRNAP escapes the promoter by dissociating initiation factors32, whereas T7 RNAP release from the promoter involves NTD refolding, which destroys the promoter-binding site within the NTD and repositions the intercalating hairpin far away from the nucleic acids. In contrast, the intercalating hairpin in mtRNAP separates the RNA transcript from the DNA template at the upstream end of the hybrid during elongation. Thus, the mechanism of transcription initiation by mtRNAP is unique. In the future, the initiation mechanism of mtRNAP should be studied structurally and functionally.

ONLINE METHODS

mtRNAP expression and purification

WT mtRNAP (residues 44–1230) and mutant mtRNAP, TFB2M and TFAM were expressed and purified as previously described31. The coding sequence of human mtRNAP used in structural studies (Δ150 mtRNAP) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cloned into the expression vector pProEx (Hb) (Invitrogen), which allowed expression of N-terminally hexahistidine-tagged protein. Mutant mtRNAPs were obtained by site directed mutagenesis using QuickChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent). The Δthumb mutant was made in the Δ104 mtRNAP background5. MtRNAP mutants used in photo cross-linking and mapping experiments were constructed using NG-less WT RNAP (residues 44–1230) described previously31 and NG-less Δ119 mtRNAP (residues 120–1230) by introducing a single asparagine–glycine pair at position 369 (T370G), 493 (Q493N), 556 (L556N) and 634 (A634G and A635G). Activity of NG mtRNAP mutants in primer extension assays was found to be similar to the activity of the WT mtRNAP.

Preparation and crystallization of mtRNAP elongation complex

Synthetic oligonucleotides were obtained from IDT DNA and Dharmacon Inc. The nucleic acid scaffolds were annealed by mixing equimolar amounts of template DNA (TS02), non-template DNA (NT02) and RNA (R14) to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, heating the mixture to 70 °C and slow cooling to room temperature. The mtRNAP elongation complex was assembled by incubating Δ150 mtRNAP (40 μM) with a 30% molar excess of elongation scaffold for 10 min at 20 °C. For crystallization the mtRNAP elongation complex was digested in situ with ArgC protease from Sigma (1000:1, w/w) for 1 h at 23 °C. Initial crystals were obtained from sitting-drop crystallization screens at the crystallization facility of the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry (Martinsried, Germany) using precipitate solution containing 8% polyethylene glycol 4000, 200 mM sodium acetate, 100 mM trisodium citrate (pH=5.5), 10% glycerol and 120 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Truncated rhombic dodecahedron crystals grew to a maximum size of approximately 0.2×0.2×0.2 mm within 4–6 days.

X-ray structure analysis

Diffraction data were collected in 0.25° increments at the protein crystallography beamline X06SA of the Swiss Light Source in Villigen (Switzerland) using a Pilatus 6M pixel detector37 and a wavelength of 0.91809 Å. (Table 1). Raw data were processed with MOSFLM35. The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER38 with the structure of human mtRNAP5. (PDB 3SPA5) as a search model. The molecular replacement solution was subjected to rigid body refinement with phenix.refine39. The model was iteratively built with COOT20 and refined with phenix.refine39 and autoBuster (Global Phasing Limited). Figures were prepared with pymol (deLano Scientific).

Transcription assays

The catalytic activity of mtRNAP mutants was analyzed using a primer extension assay as described previously40. Run-off transcription assays were performed using PCR DNA templates (50 nM) containing the LSP promoter (nucleotides 338–478 in human mtDNA) and mRNAP (150 nM), TFAM (50 nM), TFB2M (150 nM), substrate NTPs (0.3 mM) in a transcription buffer containing 40 mM Tris (pH=7.9), 10 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM DTT. Reactions were carried out at 35 °C and stopped by the addition of an equal volume of 95% formamide/0.05 M EDTA. The products were resolved using 20% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) containing 6 M urea and visualized by PhosphoImager (GE Health). Original images of all autoradiographs used in this study can be found in Supplementary Fig. 5 online.

Protein–nucleic acid photo cross-linking

RNA or DNA oligos containing photo reactive 4-thio uridine monophosphate (Dharmacon Inc.) were used to assemble RNA–DNA scaffold. For cross-linking of RNA base at –8, the elongation complex (1 μM) was assembled using R11sU–TS1–NT3 scaffold (Fig. 5) and the RNA was labeled by incorporation of [α-32P] uridine triphosphate (UTP) (800 Ci/mmol) for 5 min at room temperature. For cross-linking of RNA base at –13, the elongation complex (1 μM) was assembled using R15mt_sU–TS02–NT02 scaffold in which the RNA primer was 32P-labeled. For DNA–mtRNAP cross-linking the elongation complex (1 μM) was assembled using YMRNA1–TS35sU–YMNT1 in which TS35sU DNA was 32P-labeled. The cross-linking was activated by UV irradiation at 312 nm for 10 min at room temperature as previously described40.

Mapping of the cross-linking sites in mtRNAP

Mapping of the regions in mtRNAP that interact with RNA or DNA with CNBr, NTCB, and NH2OH was performed as described previously31. Products of the cleavage reactions were resolved using a 4–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen) and visualized by PhosphorImager™ (GE Health). Bands were identified by calculating their apparent molecular weights using protein standards (Mark 12, Invitrogen) and matched to the theoretical single-hit cleavage pattern for NTCB or CNBr (see also Supplementary Fig. 4 online).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the crystallization facility at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry. Part of this work was performed at the Swiss Light Source at the Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen, Switzerland. P.C. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, (Sonderforschungsbereich 646 and 960, Transregio 5, Graduiertenkolleg 1721, Center for Integrated Protein Science Munich, Nanosystems Initiative Munich, Graduate school for Quantitative Biosciences Munich), the Bavarian Center for Molecular Biosystems, the BioImaging Network, an Advanced Grant of the European Research Council, the Jung-Stiftung, and the Vallee Foundation (P.C.). D.T. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1GM104231) and the Foundation of University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey grant PC88-12 (D.T.).

Footnotes

Accession code. Coordinates of the mitochondrial RNA polymerase elongation complex structure have been deposited with the protein data bank under accession code 4BOC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.A. and Y.I.M. cloned mtRNAP variants and performed biochemical assays. D.T. and K.S. performed RNAP purification and prepared crystals. K.S. and A.C.M.C. performed structure determination and modelling. D.T. and P.C. designed and supervised research. K.S., A.C.M.C., D.T. and P.C. wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Masters BS, Stohl LL, Clayton DA. Yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase is homologous to those encoded by bacteriophages T3 and T7. Cell. 1987;51:89–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mercer TR, et al. The human mitochondrial transcriptome. Cell. 2011;146:645–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaspari M, Larsson NG, Gustafsson CM. The transcription machinery in mammalian mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1659:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheetham GM, Steitz TA. Structure of a transcribing T7 RNA polymerase initiation complex. Science. 1999;286:2305–2309. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringel R, et al. Structure of human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Nature. 2011;478:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temiakov D, et al. Structural basis for substrate selection by t7 RNA polymerase. Cell. 2004;116:381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steitz TA. The structural changes of T7 RNA polymerase from transcription initiation to elongation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnold JJ, Smidansky ED, Moustafa IM, Cameron CE. Human mitochondrial RNA polymerase: structure-function, mechanism and inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:948–960. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin YW, Steitz TA. The structural mechanism of translocation and helicase activity in T7 RNA polymerase. Cell. 2004;116:393–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basu RS, Murakami KS. Watching the bacteriophage N4 RNA polymerase transcription by time-dependent soak-trigger-freeze X-ray crystallography. J Biol Chem. 2012;288:3308–3311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.387712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kostyuk DA, et al. Mutants of T7 RNA polymerase that are able to synthesize both RNA and DNA. FEBS Lett. 1995;369:165–168. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00732-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sousa R, Padilla R. A mutant T7 RNA polymerase as a DNA polymerase. EMBO J. 1995;14:4609–4621. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brieba LG, Gopal V, Sousa R. Scanning mutagenesis reveals roles for helix n of the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase thumb subdomain in transcription complex stability, pausing, and termination. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10306–10313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mentesana PE, Chin-Bow ST, Sousa R, McAllister WT. Characterization of halted T7 RNA polymerase elongation complexes reveals multiple factors that contribute to stability. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:1049–1062. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durniak KJ, Bailey S, Steitz TA. The structure of a transcribing T7 RNA polymerase in transition from initiation to elongation. Science. 2008;322:553–557. doi: 10.1126/science.1163433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin YW, Steitz TA. Structural basis for the transition from initiation to elongation transcription in T7 RNA polymerase. Science. 2002;298:1387–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.1077464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tahirov TH, et al. Structure of a T7 RNA polymerase elongation complex at 2.9 A resolution. Nature. 2002;420:43–50. doi: 10.1038/nature01129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gnatt AL, Cramer P, Fu J, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II elongation complex at 3.3 A resolution. Science. 2001;292:1876–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.1059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kettenberger H, Armache KJ, Cramer P. Complete RNA polymerase II elongation complex structure and its interactions with NTP and TFIIS. Mol Cell. 2004;16:955–965. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz-Linneweber C, Small I. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins: a socket set for organelle gene expression. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nayak D, Guo Q, Sousa R. A promoter recognition mechanism common to yeast mitochondrial and phage T7 RNA polymerases. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13641–13647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900718200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velazquez G, Guo Q, Wang L, Brieba LG, Sousa R. Conservation of promoter melting mechanisms in divergent regions of the single-subunit RNA polymerases. Biochemistry. 2012;51:3901–3910. doi: 10.1021/bi300074j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray MW. Mitochondrial evolution. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a011403. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litonin D, et al. Human mitochondrial transcription revisited: only TFAM and TFB2M are required for transcription of the mitochondrial genes in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18129–18133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.128918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deshpande AP, Patel SS. Mechanism of transcription initiation by the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:930–938. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell CT, Kolesar JE, Kaufman BA. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mitochondrial transcription initiation, DNA packaging, and genome copy number. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubio-Cosials A, et al. Human mitochondrial transcription factor A induces a U-turn structure in the light strand promoter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1281–1289. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ngo HB, Kaiser JT, Chan DC. The mitochondrial transcription and packaging factor Tfam imposes a U-turn on mitochondrial DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1290–1296. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falkenberg M, et al. Mitochondrial transcription factors B1 and B2 activate transcription of human mtDNA. Nat Genet. 2002;31:289–294. doi: 10.1038/ng909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sologub M, Litonin D, Anikin M, Mustaev A, Temiakov D. TFB2 is a transient component of the catalytic site of the human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Cell. 2009;139:934–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangus DA, Jang SH, Jaehning JA. Release of the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase specificity factor from transcription complexes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26568–26574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gnatt AL, Cramer P, Fu J, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II elongation complex at 3.3 A resolution. Science. 2001;292:1876–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.1059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin YW, Steitz TA. Structural basis for the transition from initiation to elongation transcription in T7 RNA polymerase. Science. 2002;298:1387–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.1077464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karplus PA, Diederichs K. Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science. 2012;336:1030–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1218231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broennimann C, et al. The PILATUS 1M detector. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2006;13:120–130. doi: 10.1107/S0909049505038665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. A robust bulk-solvent correction and anisotropic scaling procedure. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:850–855. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905007894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Temiakov D, Anikin M, McAllister WT. Characterization of T7 RNA polymerase transcription complexes assembled on nucleic acid scaffolds. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47035–47043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.