SUMMARY

Bacteria have evolved pathways to metabolize phosphonates as a nutrient source for phosphorus. In Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021, 2-aminoethylphosphonate is catabolized to phosphonoacetate, which is converted to acetate and inorganic phosphate by phosphonoacetate hydrolase (PhnA). Here we present detailed biochemical and structural characterization of PhnA that provides insights into the mechanism of C-P bond cleavage. The 1.35 Å resolution crystal structure reveals a catalytic core similar to those of alkaline phosphatases and nucleotide pyrophosphatases, but with notable differences such as a longer metal-metal distance. Detailed structure-guided analysis of active site residues and four additional co-crystal structures with phosphonoacetate substrate, acetate, phosphonoformate inhibitor, and a covalently-bound transition state mimic, provide insight into active site features that may facilitate cleavage of the C-P bond. These studies expand upon the array of reactions that can be catalyzed by enzymes of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily.

INTRODUCTION

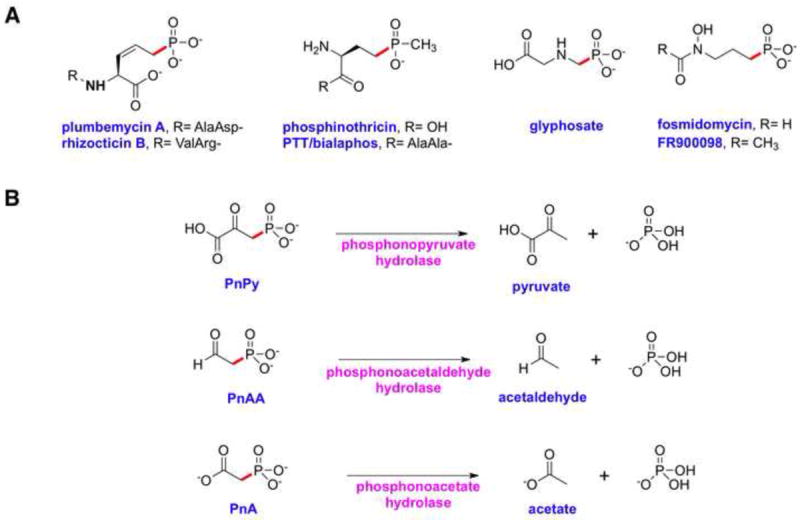

Phosphonic and phosphinic acids contain a stable carbon-phosphorus (C-P) bond in place of the oxygen-phosphorus (O-P) bonds found in phosphate esters (Metcalf and van der Donk, 2009). These compounds are ubiquitous in biological systems, as exemplified by their occurrence in lipids, exopolysaccharides, and glycoproteins. The structural resemblance of several small molecule phosphonates to the corresponding phosphoric acid esters and anhydrides renders these phosphonates competitive inhibitors of enzymatic processes involved in phosphoryl transfer reactions. Phosphonates with biological activities include antifungals (rhizocticin), herbicides (glyphosate and phosphinothricin tripeptide, PTT), antibacterials (dehydrophos and fosfomycin), and antimalarials (fosmidomycin and FR900098) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of representative phosphonates and enzyme activities that result in the cleavage of C-P bonds. (A) Chemical structures of phosphonates with demonstrated biological activity. (B) Enzymatic cleavage of C-P bonds in phosphonate substrates containing an electron withdrawing β-carbonyl group.

A characterization of marine dissolved organic matter estimates that phosphonic acids constitute nearly one quarter of the available phosphorus in the world’s oceans and in some organisms phosphonates represent the most abundant of sources of phosphorus (Clark, et al., 1999). Given this prevalence, it is not surprising that several microorganisms have evolved pathways for the degradation of phosphonates for use as sources of carbon and phosphorus (Quinn et al., 2007; White and Metcalf, 2007). Thus far, four different enzyme activities that cleave C-P bonds have been identified and these can be divided into two mechanistic classes (Kononova and Nesmeyanova, 2002). The first class consists of carbon-phosphorus lyases, membrane-associated multi-enzyme systems that can directly cleave unactivated C-P bonds of several structurally diverse substrates, presumably using redox chemistry (Wackett, et al., 1987). The second class consists of enzymes acting on phosphonates that contain an electron withdrawing β-carbonyl group, and include phosphonopyruvate (PnPy) hydrolase, phosphono-acetaldehyde (PnAA) hydrolase, and phosphonoacetate (PnA) hydrolase (Figure 1B). Phosphonopyruvate hydrolase acts on PnPy that is reversibly generated from either phosphonoalanine by PnPy transaminase or from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) by PEP phosphomutase (Chen et al., 2006). Phosphonoacetaldehyde hydrolase hydrolyzes PnAA that is produced from phosphonopyruvate by PnPy decarboxylase (Morais et al., 2000). Phosphonoacetate hydrolase cleaves PnA to yield acetate and inorganic phosphate (Pi) (McGrath, et al., 1995).

Although the biogenic origin of PnA has only recently gained some experimental support (Panas, et al., 2006), PnA hydrolysis activity was observed in the crude extracts of Pseudomonas fluorescens 23F (McMullan, et al., 1992). The enzyme was purified from the native producer, and shown in vitro to catalyze the zinc-dependent hydrolysis of PnA (McGrath, et al., 1995). Subsequently, the corresponding gene (designated phnA) was cloned and the gene-product was heterologously produced in bacteria (Kulakova, et al., 1997). PnA hydrolysis activity has since been demonstrated in other Pseudomonas spp. (Panas, et al., 2006), Penicillium spp. (Forlani, et al., 2006), marine bacteria, and coral holobionts (Thomas, et al., 2010), establishing the presence of PhnA-mediated PnA hydrolysis in the microbial metabolome.

Primary analysis reveals PhnA to be a member of the alkaline phosphatase (AP) superfamily (Coleman, 1992, Galperin, et al., 1998, Kulakova, et al., 1997). Alkaline phosphatases, and the related nucleotide pyrophosphatases/phosphodiesterases (NPPs), catalyze the hydrolysis of phosphate monoesters and diesters, respectively. The active site of these enzymes consists of a binuclear metal core and contains a catalytically required Ser or Thr that generates a covalent phosphoenzyme intermediate (Holtz, et al., 1999). Alkaline phosphatases from disparate sources differ in the identity of the divalent metal ions in the active site (Wojciechowski, et al., 2002). The metal ion specificity is rendered in part by the identity of the active site residues and can be changed by mutagenesis of the metal-coordinating amino acid side chains (Wang et al., 2005; Wojciechowski and Kantrowitz, 2002).

Compared to the extensive investigations into the mechanism and substrate specificity of phosphate monoester and diester hydrolysis, the hydrolysis of phosphonates is a much less studied activity within the catalytic repertoire of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. The mechanism by which a member of the AP superfamily catalyzes this process is of great interest given the very different, carbon-based leaving group in C-P bond hydrolysis. In order to elucidate the mechanistic basis for C-P (rather than O-P) bond hydrolysis, we present detailed kinetic and structural studies of PhnA from Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. Crystal structures of the wild-type enzyme confirm structural similarity to alkaline phosphatases but with notable differences that likely direct activity towards the cleavage of a C-P bond. Kinetic analyses of metal-substituted PhnA and corresponding anomalous scattering diffraction experiments on zinc- and manganese-containing PhnA establish the in vitro metal preference. Co-crystal structures with substrate PnA, product acetate ion, inhibitor phosphonoformate (PnF), and the transition state mimic vanadate, together with kinetic and structural analysis of site-specific active site variants, suggest a plausible mechanism for PnA hydrolysis by PhnA. Our results expand upon a very recent study of a PnA hydrolase from P. fluorescens 23F (Kim, et al., 2011).

RESULTS

Overall structure

The PhnA protein from S. meliloti was heterologously produced in Escherichia coli with an amino-terminal hexahistidine tag. For crystallization, the tag was removed via thrombin protease cleavage. Initial crystallographic phases for the wild-type PhnA were determined by single wavelength anomalous diffraction data collected on crystals grown from selenomethionine-labeled protein, and the structure has been subsequently refined against data to 1.35 Å resolution to a free R value of 21%. Relevant data collection and refinement statistics are provided in Table 1. The overall structure of PhnA is shown in Figure 2A.

Table 1.

Data collection, phasing and refinement statistics.

| PhnA (native) | PhnA-Vanadate | T68A PhnA-PnA | PhnA-Acetate | PhnA-PnF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | P43212 | P43212 | P43212 | P43212 | P43212 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 111.8, 111.8, 72.8 | 111.1, 111.1, 72.4 | 111.4, 111.4, 72.8 | 111.4, 111.4, 72.9 | 111.6, 111.6, 72.5 |

| Resolution (Å)1 | 50-1.35 (1.4-1.35) | 50-1.8 (1.83-1.8) | 40-2.0 (2.07-2.0) | 50-2.0 (2.03-2.0) | 50-1.6 (1.66-1.6) |

| Rsym (%) | 6.8 (60.8) | 6.5 (69.3) | 7.5 (47.4) | 7.1 (16.9) | 8.0 (38.0) |

| I / σ(I) | 36.8 (1.7) | 36.2 (2.2) | 32.1 (2.5) | 47.5 (5.5) | 33.0 (3.9) |

| Completeness(%) | 98.3 (84.6) | 98.0 (91.6) | 99.4 (94.3) | 100.0 (99.9) | 99.3 (96.4) |

| Redundancy | 10.4 (4.0) | 10.9 (7.8) | 11.2 (5.5) | 11.3 (10.9) | 11.3 (9.0) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 25.0-1.35 | 25.0-1.8 | 25.0-2.0 | 25.0-2.0 | 25.0-1.6 |

| No. reflections | 94,012 | 39,623 | 29,711 | 29,946 | 57,337 |

| Rwork / Rfree2 | 19.7/20.9 | 20.5/24.1 | 18.9/23.4 | 17.6/21.9 | 19.3/21.6 |

| Number of atoms | |||||

| Protein | 3204 | 3194 | 3192 | 3199 | 3200 |

| Metal | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ligand | - | 5 | 8 | 4 | 7 |

| Water | 583 | 351 | 280 | 379 | 565 |

| B-factors | |||||

| Protein | 13.8 | 28.3 | 32.2 | 17.2 | 15.8 |

| Metal | 19.3 | 32.4 | 25.6 | 45.4 | 13.8 |

| Ligand | - | 31.8 | 36.8 | 25.6 | 21.5 |

| Water | 28.5 | 34.7 | 36.1 | 28.2 | 20.0 |

| R.m.s deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.19 | 1.12 | 1.08 |

Highest resolution shell is shown in parenthesis.

R-factor = Σ (|Fobs|-k|Fcalc|)/ Σ |Fobs|and R-free is the R value for a test set of reflections consisting of a random 5% of the diffraction data not used in refinement.

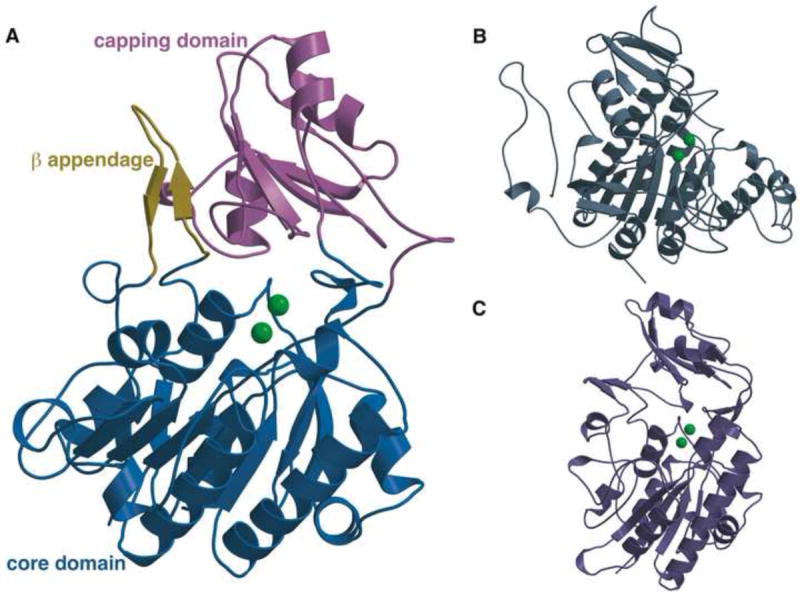

Figure 2.

Overall structure of PhnA as compared to structures of AP and NPP. (A) Structure of PhnA showing the core catalytic domain that is conserved amongst members of the AP superfamily (blue) and the β appendage (yellow) and capping domain (pink) that are specific to PhnA and NPP. The two metal ions are shown as green spheres. (B) Structure of E. coli AP (PDB Code: 1B8J). (C) Structure of X. axonopodis NPP (PDB Code: 2GSO).

The structure of PhnA consists of two distinct domains, a core domain that is highly homologous within members of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily (Figure 2B, 2C), and a divergent capping domain that has only previously been observed in the structure of NPP from Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri (Figure 2C) (Zalatan et al., 2006) and very recently, in the crystal structure of PnA hydrolase from P. fluorescens 23F (Kim, et al., 2011). The core domain comprises residues Met4-Gly85, Asp104-Met253, and Ser376-Ala416 and consists of a seven-membered β sheet flanked by eight α helices on either side. The capping domain has a typical α/β/α fold and is composed of residues Lys254-Arg375. Of particular note is the β-loop-β appendage comprising of residues Ile86-Asn103, which extends from the helices of the core domain and contacts the central β sheet of the capping domain (Figure 2A). This appendage is also present in the crystal structure of NPP (Zalatan et al., 2006) (Figure 2C), but absent in the structures of alkaline phosphatases that hydrolyze phosphate monoesters (Figure 2B). The structures described here are more complete and of higher resolution than the previously reported structure of P. fluorescens 23F PnA hydrolase (PDB ID: 1EI6) (Kim, et al., 2011), in which several residues proximal to the active site were disordered and consequently were not modeled. Of note the current structure presents complete modeling of all residues of the β-loop-β appendage and all surface loops of the core domain.

Active site metal ions

Members of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily are characterized by the presence of two requisite metal ions, and the nature of the metal-coordinating protein ligands is highly conserved (Coleman, 1992). Likewise, PhnA contains two metal ions (referred to as M1 and M2, consistent with nomenclature for this superfamily) with M1 coordinated by His215, His377, and Asp211 and M2 coordinated by Asp29, Asp250, and His251 (Figures 3A and S1A). As in other members of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily, metal M2 likely activates the catalytic Thr68 for nucleophilic attack at the phosphorus atom (Ghosh et al., 1986; Kim et al., 2011; Schwartz and Lipmann, 1961) and metal M1 likely activates a water molecule for nucleophilic displacement at the phosphorus atom during hydrolysis of the phosphorylated enzyme intermediate (Coleman, 1992). The two metal ions also contribute to electrostatic stabilization of the negative charge on the non-bridging oxygens during catalysis of P-O bond cleavage (Lassila and Herschlag, 2008, Nikolic-Hughes, et al., 2005).

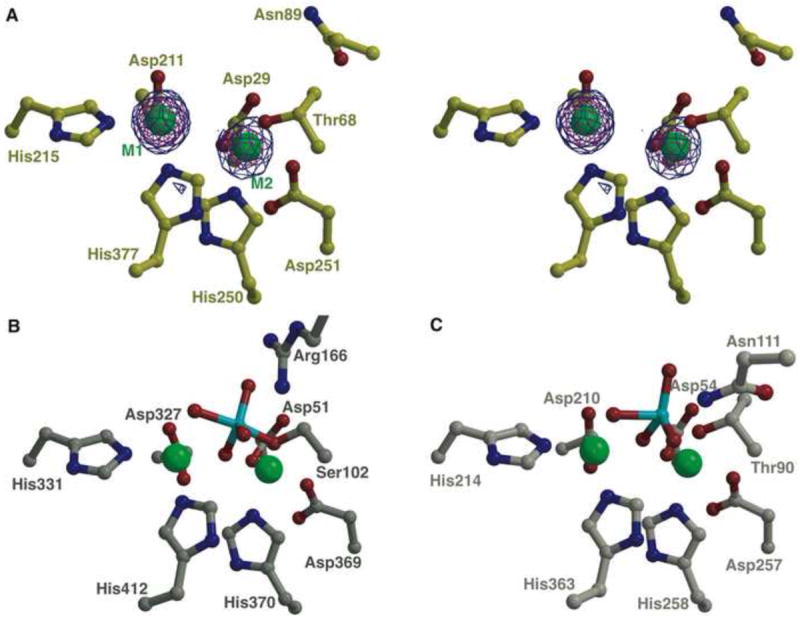

Figure 3.

Active site view of PhnA as compared to AP and NPP. (A) Stereo view of PhnA active site showing a Bijvoet difference map, calculated using Fourier coefficients |F(+)| and |F(-)| from data collected at the zinc absorption edge and phases from the final refined model without any metal ions. The map is contoured at 3σ (in blue) and 10σ (in red). The coordinates from the final refined model are superimposed and the two metal ions are shown as green spheres. The active site view (B) of E. coli AP (PDB Code: 1B8J) and (C) of X. axonopodis NPP (PDB Code: 2GSO), both in complex with the inhibitor vanadate (colored in cyan), are shown for comparison. Water molecules are omitted for clarity. See also Figure S1A.

The bound metal ions in PhnA (as purified from heterologous overexpression in E. coli) are zinc ions; their identity and location were determined using anomalous diffraction data collected at the zinc absorption edge (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the distance between the two metal ions was 4.6 Å. This distance is significantly greater than the distance between the metal ions in E. coli AP (4.26-4.28 Å; PDB ID: 1ED9) (Figure 3B) and NPP (4.26-4.36 Å; PDB ID: 2GSN) (Figure 3C), and to the best of our knowledge is greater than the distance reported for any other alkaline phosphatase superfamily members (Stec et al., 2000; Zalatan et al., 2006). A similarly long metal-metal distance was also reported for the PnA hydrolase from P. fluorescens (4.47 Å) (Kim, et al., 2011).

In alkaline phosphatases, a third metal (typically magnesium) is located in the active site and was postulated to be critical for deprotonation of the serine side chain to generate the alkoxide nucleophile (Kim and Wyckoff, 1991). This third metal is absent in PhnA, as has also been observed in the structure of NPP (Zalatan et al., 2006). Absence of the third metal ion in NPP has led to re-evaluation of its role in phosphoryl group transfer reactions mediated by alkaline phosphatases. More recent studies comparing the reactivities of monoester and diester substrates suggest that the magnesium ion stabilizes a non-bridging oxygen atom in the transition state for phosphate monoester hydrolysis (Zalatan, et al., 2008). In the PhnA structure, side chains of residues Cys27, Asp29, Asn72, Tyr206, and Thr208 form a hydrogen bonding network replacing the region corresponding to the third metal site in alkaline phosphatases. The mechanistic implications of the absence of this third metal in the structure of PhnA are not immediately clear.

Metal ion specificity

Alkaline phosphatases can utilize a vast array of divalent metal ions in the catalytic M1 and M2 positions, with the metal ion specificity subject to change by alterations in the active site amino acid side chains (Wojciechowski and Kantrowitz, 2002). To probe the specific metal ion preference for PhnA, we monitored the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme that was overexpressed and purified from E. coli, and after its incubation with Mg2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Fe2+, and Mn2+ (Table 2 and Figure S2). As previously reported (Borisova, et al., 2011), the enzyme purified from E. coli efficiently catalyzed the hydrolysis of PnA without addition of metal ions. When PhnA was incubated with Zn2+ prior to the activity assay, a small improvement in kcat was observed along with an increase in KM. However, when PhnA was pre-incubated with Mn2+ or Fe2+, two-to-three fold improvement in kcat was observed with only small variations in the KM values (Table 2). Activity assays in the presence of Mg2+ or Co2+ resulted in decreased kcat values with a substantially lower KM value of PhnA reconstituted with Co2+ compensating for the lower turnover number of this enzyme.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for PnA hydrolysis by PhnA in the presence of different metal ions (10 μM). See also Table S1.

| PhnA-N-His | kcat, s-1 | KM, μM | kcat/KM, M-1s-1 | kcat/KM, rel. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As isolateda | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 22 ± 2 | 4.1 × 104 | 1 |

| + Zn2+a | 1.06 ± 0.02 | 37 ± 2 | 2.9 × 104 | 0.7 |

| + Fe2+ | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 43 ± 5 | 8.4 × 104 | 2.0 |

| + Mn2+ | 2.60 ± 0.07 | 34 ± 3 | 7.7 × 104 | 1.9 |

| + Co2+ | 0.57 ± 0.02 | 11 ± 2 | 5.1 × 104 | 1.2 |

| + Mg2+ | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 34 ± 5 | 0.5 × 104 | 0.1 |

| Apo PhnA | No activity detected | |||

| + Mn2+ | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 34 ± 3 | 16.2 × 104 | 4.0 |

| + Fe2+ | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 44 ± 8 | 8.0 × 104 | 2.0 |

| + Zn2+ | 1.16 ± 0.03 | 30 ± 3 | 3.8 × 104 | 0.9 |

Reported in (Borisova, et al., 2011)

Enzyme purified from E. coli was treated with the metal ion chelator ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) to remove the metal ions already bound to the enzyme. The resulting apo-PhnA was devoid of enzymatic activity. However, the activity was fully reconstituted by brief incubation of PhnA with different divalent metal ions prior to the activity assays (Table 2 and Figure S2). Thus, addition of Zn2+ produced a form of PhnA with kinetic parameters nearly identical to those of the as-isolated enzyme. The greatest increase in the enzymatic activity was observed upon reconstitution of EDTA-treated PhnA with Mn2+ resulting in a kcat/KM value four-fold higher than that found for as-isolated PhnA. When combinations of equal concentrations of either Fe2+ and Zn2+ or Mn2+ and Zn2+ were tested for apo-PhnA reconstitution, the activity of the enzyme did not exceed that of Zn-reconstituted PhnA (Table S1) suggesting that it is present predominantly as the Zn-bound form in either preparation and that PhnA has the greatest affinity for Zn2+. The identity of the PhnA-bound metal ion(s) in PhnA reconstituted with different metals could not be characterized directly because of partial dissociation of the bound metal ions from PhnA during attempts to separate the protein from the constituents of the reconstitution buffer.

In order to probe whether differences in activity were a consequence of structural changes between the zinc and manganese substituted enzymes, we collected anomalous diffraction data on Mn2+-substituted PhnA. Double difference Fourier maps were calculated which showed unambiguous positive density for metal ions in the M1 and M2 positions only at the manganese absorption edge assuring that both sites of the recombinant PhnA were occupied by manganese under the conditions used. The structure of Mn2+-PhnA is virtually identical to that of Zn2+-PhnA including the metal-metal distance (4.6 Å), suggesting that the structural results detailed below are valid for enzyme containing either metal. It should be noted that the values of kinetic constants observed for any of the metal-bound forms of PhnA (Table 2) are within the physiologically relevant range. Thus, it is possible that the identity of the PhnA-bound metal in vivo is determined not only by the affinity of the PhnA metal-binding sites but also by the intracellular levels of metal ions in S. meliloti, which have not been reported to date.

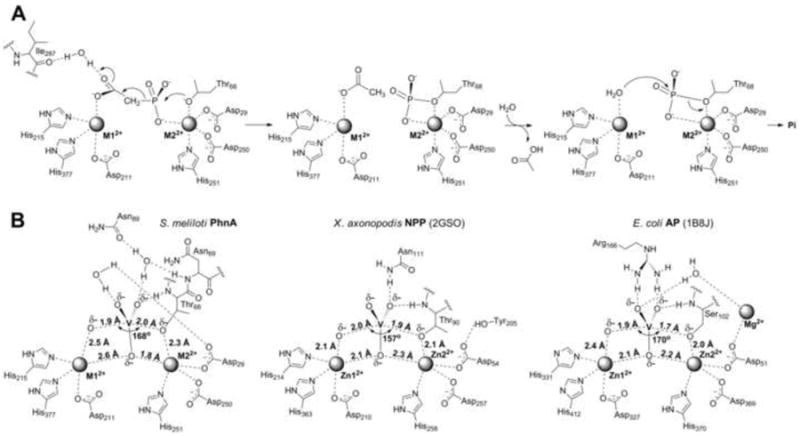

Model for a transition state structure

Hydrolysis of phosphate esters by alkaline phosphatases takes place by an in-line double displacement mechanism in which the alkoxide ion, generated on a serine or threonine side chain, first attacks the tetracoordinated phosphorus atom. This displacement of a metal-stabilized leaving group by the enzyme nucleophile occurs via a trigonal bipyramidal transition state, leading to the formation of a covalent phosphoseryl (or phosphothreonyl) intermediate (Coleman, 1992). Hydrolysis of this intermediate involves attack of a M1-bound hydroxide onto the phosphorus atom displacing the Ser/Thr via another trigonal bipyramidal transition state. The covalent adduct of orthovanadate ion with the catalytic serine or threonine side chain mimics the trigonal bipyramidal geometry of the transition state with the nucleophile and the leaving group occupying the axial positions; three of the oxygen atoms attached to the vanadium atom occupy the equatorial positions. Complexes with vanadate have been reported for both AP and NPP and have led to insights into the stabilization of the reaction transition state (Holtz et al., 1999; Zalatan et al., 2006), and have facilitated the identification of stabilizing interactions for each of the equatorial oxygen atoms. For both enzymes, one oxygen atom is directed in between the metal ions and is stabilized by electrostatic interactions. Two other equatorial oxygen atoms in E. coli AP are stabilized by interactions with the guanidinium group of Arg166. For NPP, in which phosphate diester hydrolysis results in two, instead of three, non-bridging equatorial oxygen atoms, Asn111 (in X. axonopodis) interacts with one of these oxygen atoms to stabilize the transition state.

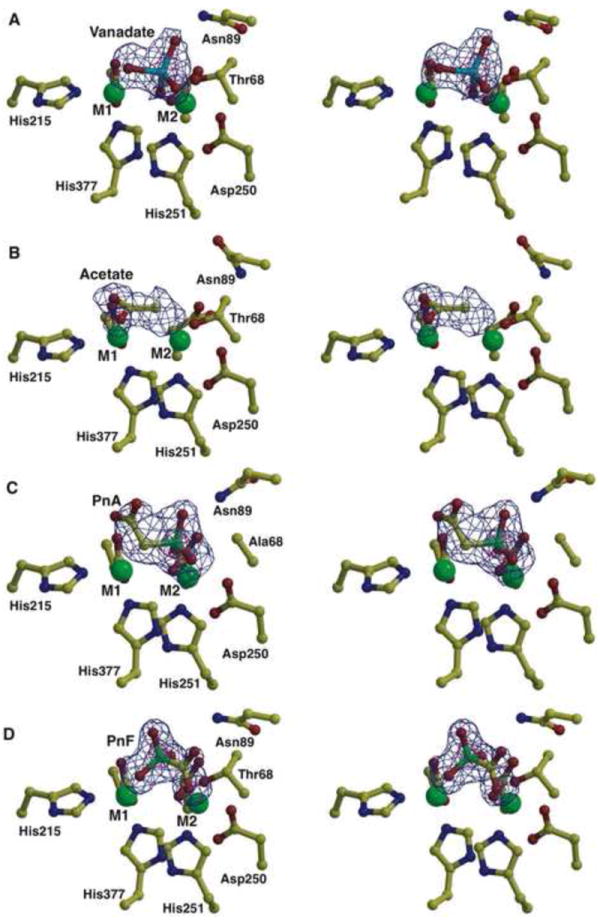

In order to delineate the interactions that occur in the transition state for phosphonate C-P bond hydrolysis by PhnA, we have determined the co-crystal structure of a covalent complex with orthovanadate at 1.65 Å resolution (Figure 4A). As observed for NPP (Zalatan, et al., 2006) and AP (Holtz, et al., 1999), the trigonal bipyramidal structure of the orthovanadate adduct is slightly distorted, with the O-V-O bond angle for the axial oxygens being 168° in PhnA compared to 157° for NPP and 170° for AP. But unlike AP and NPP, the three equatorial oxygens are not in a plane with the vanadate atom but tilted towards the M2 ion (Figure 4A). A decrease in the distance between the two zinc ions of 0.3 Å is observed compared to the structure of unliganded PhnA. The side chain hydroxyl of Thr68 is placed in one of the axial positions and the oxygen atom at the other axial position interacts with the zinc ion in the M1 site, which corresponds to the leaving group stabilization by the metal ion in a phosphate ester hydrolysis reaction. One of the equatorial oxygen atoms is situated in between the zinc atoms at a distance of 1.8 Å to M2 and a longer distance of 2.6 Å to M1, while a second equatorial oxygen is within hydrogen bonding distance (2.7 Å) of the amide bond nitrogen of Thr68 (Figure S1B). However, unlike NPP, where an additional hydrogen bond from the side chain of Asn111 further stabilizes the equatorial oxygen, no appropriately placed amino acid side chains are within hydrogen bonding distance. The strictly conserved Asn89, corresponding to Asn111 of NPP, is too distant (5.46-5.65 Å) to be involved in a direct contact. A water molecule coordinated by the side chain of Asn89 is placed 3.5 Å away from this equatorial oxygen and this water molecule additionally interacts with the backbone nitrogen of Asn69 (Figure S1B). When Asn89 was replaced with valine the catalytic activity of the PhnA-N89V mutant was reduced approximately 104-fold as compared to the wild-type PhnA (Table S1). A crystal structure of the N89V mutant determined at 1.8 Å resolution revealed that both metal ions are preserved in the mutant structure and no major rearrangements of the amino acid side chains around the active site could be observed. However, the arrangement of the water molecules in the active site is different from that of the wild-type enzyme (data not shown) supporting the contribution of the water-mediated contact to the Asn89 side chain to transition state stabilization. In AP, the third equatorial oxygen atom is hydrogen bonded to Arg166; in NPP, this oxygen carries a substituent in the phosphodiester substrate and does not have any interaction partners in the NPP crystal structure. In PhnA, this third oxygen makes water-mediated contacts in the PhnA-vanadate structure (Figure S1B). A water molecule, hydrogen bonded to the carboxylate side chain of Asp29, is positioned 3.2 Å away.

Figure 4.

Stereo views of PhnA active site with ligands bound. (A) Stereo view showing the active site features of the PhnA-vanadate structure. The vanadate is colored in cyan, polypeptide residues are shown in yellow and the active site metals are shown as green spheres. Superimposed is a difference Fourier electron density map (contoured at 3σ over background in blue and 8σ over background in pink) calculated with coefficients |Fobs| -|Fcalc| and phases from the final refined model with the coordinates of vanadate deleted prior to one round of refinement. (B) Stereo view of the active site features of the PhnA-acetate complex. Residues are colored as above and superimposed is a difference Fourier electron density map (contoured at 3σ over background in blue) calculated with coefficients |Fobs| - |Fcalc| and phases from the final refined model with the coordinates of acetate deleted prior to one round of refinement. (C) Stereo view of the active site features of the PhnA-T68A-PnA complex. Residues are colored as above and superimposed is a difference Fourier electron density map (contoured at 3.3σ over background in blue and 10σ over background in pink) calculated with coefficients |Fobs| -|Fcalc| and phases from the final refined model with the coordinates of PnA deleted prior to one round of refinement. (D) Stereo view of the active site features of the PhnA-PnF complex. Residues are colored as above and superimposed is a difference Fourier electron density map (contoured at 3σ over background in blue and 8σ over background in pink) calculated with coefficients |Fobs| - |Fcalc| and phases from the final refined model with the coordinates of PnF deleted prior to one round of refinement. In all panels, water molecules are omitted for clarity. See also Figures S1 and S3.

Crystal structure of PhnA with acetate bound

Diffraction data from crystals of wild-type PhnA soaked with PnA reveal the appearance of electron density consistent with an acetate ion bound to the M1 metal ion (Figures 4B and S1C). Two lines of evidence suggest that the resultant electron density for acetate derives from turnover of the PnA substrate by PhnA: first, diffraction data from crystals grown under identical conditions but without the addition of PnA do not show density for acetate; second, no contamination of acetate could be detected in samples of PnA used for co-crystallization as determined by proton NMR spectroscopy.

In the 2.0 Å resolution PhnA-acetate co-crystal structure, both oxygen atoms of the acetate ion are coordinating to the M1 metal ion at a distance of 2.1 Å (Figure 4B). Coordination of the two oxygen atoms of the carboxylate moiety of acetate by the M1 metal ion places the methyl group of acetate 2.4 Å from the M1 metal ion and 3.9 Å from the M2 metal ion. Although not observed in the structure, the spacing between the acetate and M2 metal ion is sufficient to accommodate a phosphate group covalently bound to Thr68. One water molecule is positioned 2.85 Å away from the methyl group of the acetate and is stabilized by hydrogen bond interactions with the backbone carbonyl of Ile287 and backbone amide nitrogen of Asn69 (Figure S1C).

Co-crystal structure of PhnA-T68A with phosphonoacetate

Attempts at co-crystallization of wild-type PhnA enzyme, or soaking of apo wild-type enzyme crystals with substrate PnA were unsuccessful as, across all concentrations of substrate employed, catalytic turnover of the substrate lead to incorporation of the acetate ion in the active site of the enzyme and no density of the phosphate moiety could be observed. Hence co-crystallization of PnA with a T68A mutant (exhibiting an approximately 103-fold decrease in activity, Table S1) was attempted. Crystals for the T68A mutant showed robust density for PnA in the active site (Figures 4C and S1D). The identity of the ligand is affirmed by the presence of strong electron density at a position corresponding to the electron-dense phosphorus atom of the substrate. The phosphonate group of the substrate molecule is bound in a manner consistent with the transition state model predicted by the vanadate covalent crystal structure. The phosphorus atom is 3.4 Å away from the side chain methyl group of alanine at position 68 (corresponding to the position of the Thr nucleophile). One oxygen atom of the phosphonate of PnA points towards the M2 metal ion and is positioned at a distance of 1.99 Å. A second oxygen atom is hydrogen bonded to the backbone amide of Ala68, 2.69 Å from the amide nitrogen. This oxygen also engages in a water-mediated contact with the side chain of Asn69. A water mediated hydrogen bond also exists between Asp29 and the third phosphonate oxygen atom (Figure S1D). Superposition of the apo wild-type PhnA structure onto the PhnA-T68A-PnA structure positions the catalytic threonine side chain hydroxyl 1.8 Å from the phosphorus atom and the theoretical bond angle between the hydroxyl oxygen, phosphorus atom and methylene group of PnA is 163°, close to the 168° seen for the vanadate transition state mimic. For comparison, the bond length between the vanadate atom and the catalytic threonine hydroxyl oxygen in the covalent complex is 2.0 Å. Thus the position of the phosphonate group in the T68A mutant is slightly skewed towards the threonine hydroxyl as compared to the vanadate transition state model.

The acetate moiety of the substrate is bound in a different manner to the T68A mutant compared to the acetate-bound state of the wild-type enzyme described above. While the acetate ion binds to the M1 metal ion in a bidentate manner in wild-type PhnA, the substrate acetate moiety binds to M1 of the T68A mutant in a monodentate fashion with one of the oxygen atoms at a distance of 2.5 Å from M1 and the second oxygen pointing away from the metal, and hydrogen bonded to a solvent molecule. This water in turn is hydrogen bonded to the backbone carbonyl of Ile287 (Figure S1D). The distance of the methylene group of PnA to the M1 metal ion is 2.2 Å, close to the observed distance of 2.4 Å between the M1 ion and the methyl group of bound acetate; the distance to M2 is 4.4 Å. As a consequence of binding of the substrate to both metals, the carbon-carbon-phosphorus bond angle is quite small (102°) with the carbon-phosphorus bond oriented in a way that upon its cleavage would allow electron delocalization into the π system of the metal-bound carboxylate. Hence, it appears that the bound conformation of PnA to the T68A mutant resembles the productive complex for catalysis.

The suggested mode of monodentate stabilization of an enolate intermediate by a metal ion is reminiscent of mandelate racemase (Gerlt, et al., 2005). Mechanistic and crystallographic studies of this enzyme have demonstrated that an enolate intermediate of mandelate is stabilized by a divalent magnesium ion that binds only one of the oxygen atoms of the intermediate. This oxygen also interacts with a Lys. The second oxygen atom of the enolate of mandelate is coordinated by a strictly conserved glutamate side chain (Kallarakal, et al., 1995), and the enolate anion is further stabilized by resonance with an aromatic ring. In PhnA, only a water is hydrogen bonded to the second oxygen of the carboxylate.

Crystal structure of inhibitor phosphonoformate-bound PhnA

Kinetic analyses in this and previous studies (Kim, et al., 2011, McGrath, et al., 1995) have identified PnF as an inhibitor of PnA hydrolase. We determined competitive inhibition of PhnA by PnF with a KI value of 32.9 ± 6.8 μM (see Supplemental Information and Figure S3). Quinn and coworkers hypothesized that the inhibition of PnA hydrolase from P. fluorescens 23F could be due to the similar structures of PnA and phosphonoformate (McGrath, et al., 1995). In order to delineate the inhibitory mechanism of PnF, we determined the crystal structure of PhnA in the presence of PnF to a resolution of 1.6 Å (Figure 4D). While no rearrangement of the metal binding side chains was observed, the distance between the zinc ions increased to 4.7 Å.

Compared to the binding of PnA, the phosphonate moiety of PnF is bound to the M1 zinc ion, not the M2 ion. The orientation and position of the PnF is similar to that observed previously in the co-crystal structure of P. fluorescens 23F PhnA (Kim, et al., 2011). One oxygen atom of the phosphonate is stabilized by electrostatic interactions with the M1 ion positioned 1.85 Å away (Figure 4D). A water-mediated hydrogen bonding interaction also exists between a second oxygen atom of the phosphonate moiety and the side chain of Asp29. Similarly, the third oxygen atom interacts with the side chain of Asn89 through a water-mediated hydrogen bond. However, the phosphonate is oriented away from the catalytic nucleophile Thr68 (3.4 Å) and the formate is oriented towards this residue, resulting in the inhibitor binding in a backward fashion. The angle defined by the oxygen atom of the Thr68 side chain and the C-P bond is 71°, suggesting that inhibitor binding does not mimic substrate binding. Given the predicted geometry for the transition state of P-O bond formation and P-C bond cleavage, PnF appears to bind in a non-productive manner through various stabilizing interactions. The carboxylate group is positioned towards the sites of the vanadate equatorial oxygen atoms. One of the carboxylate oxygen atoms is 3.0 Å away from the backbone amide of Thr68 and is involved in a hydrogen bonding interaction, and the other oxygen atom interacts with a water molecule, which in turn is hydrogen-bonded to the side chain of Asn89 and backbone amide of Asn69. Hence, based upon the PnA co-crystal structure and vanadate covalent complex structure, inhibition of enzymatic activity by PnF does not seem to be dependent upon an analogous binding mode of the substrate and inhibitor molecules, but rather upon the tight but non-productive binding interactions of this molecule in the active site of the enzyme.

DISCUSSION

Currently four phosphonate catabolic pathways involving cleavage of the C-P bond are known. Apart from the poorly characterized and highly promiscuous C-P lyase pathway, the C-P bond-cleaving enzymes in the other three pathways require the presence of a β-carbonyl moiety adjacent to the phosphorus atom. However, the utilization of this β-carbonyl moiety by the three enzymatic mechanisms is vastly different. The PnAA hydrolyzing enzyme uses this group to generate a Schiff-base intermediate that activates the phosphonate group for attack by an active site nucleophile and provides resonance stabilization for the developing negative charge on carbon (Morais et al., 2000). PnPy hydrolase utilizes the β-carbonyl group for stabilization of the pyruvate leaving group by delocalizing the developing negative charge on the methylene group to the carbonyl oxygen (Chen et al., 2006; Kulakova et al., 2003; Ternan et al., 2000). The mechanism employed by PnA hydrolase suggested by the co-crystal structures presented here, also employs charge delocalization onto the β-carbonyl (Figure 5A). The enolate dianion thus formed appears to be further stabilized by coordination to the M1 metal ion, in a mechanism reminiscent of the enolase superfamily enzymes (Gerlt, et al., 2005). In most members of the enolase superfamily the metal (Mg2+) binds to both oxygens of the carboxylate of the substrate that will carry the majority of the charge upon enolate formation. Only for mandelate racemase and related enzymes is bidentate binding not observed and only one of the carboxylate oxygens is coordinated to a Mg2+ ion, similar to the observations in this study for PhnA.

Figure 5.

Putative mechanism for PnA hydrolysis by PhnA. A. Proposed mechanism for PhnA. B. Scheme of S. meliloti PhnA active site structure with vanadate bound used as transition state model as compared to AP (PDB Code: 1B8J) (Holtz, et al., 1999) and NPP (PDB Code: 2GSO) (Zalatan, et al., 2006).

From our data, the stabilization of developing negative charge on the leaving group by the M1 metal ion appears to be a conserved feature of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily members, albeit the manner by which the active site geometry is used differs considerably from phosphate ester hydrolysis. Compared to AP and NPP, PhnA must activate a much weaker, carbon-based leaving group instead of an oxygen-based leaving group. As a measure of leaving group ability, the pKa of the conjugate acid of the acetate enolate is likely to be >30 (Richard and Amyes, 2001) compared to a typical alcohol pKa of ~15-18. In addition to the different leaving group ability, the charge distribution on the leaving group is also significantly different. During phosphate ester hydrolysis, significant charge build-up occurs on the bridging oxygen of the leaving group and this charge is stabilized by the M1 ion (O’Brien and Herschlag, 2002, Zalatan, et al., 2007). For phosphonate hydrolysis, the charge is delocalized such that most of the charge likely resides on the oxygens of the acetate enolate (Figure 5A). This charge would be situated further from the oxygen of the Thr nucleophile coordinated to the M2 ion. Thus, a longer metal-metal distance appears to be required to simultaneously stabilize the developing charge on the leaving group with the M1 ion and activate the Thr nucleophile with the M2 ion. The involvement of Thr68 as a nucleophile is supported by a recent study on PhnA from P. fluorescens (Kim, et al., 2011) that reported loss of activity when the corresponding residue was mutated and that demonstrated labeling of the Thr hydroxyl with a phosphate group when incubated with γ–32P-ATP, a slow substrate for PhnA. Thus, only the relatively long Zn-Zn distance allows the PnA substrate to simultaneously bind to both metals in a conformation that supports formation of an acetate enolate intermediate.

How PhnA can stabilize the much weaker leaving group with essentially the same active site architecture as that of AP and NPP to achieve effective catalysis is at present not clear. Unlike the extensive studies of enzymatic and non-enzymatic hydrolysis of phosphate monoesters and phosphate diesters, which have provided a detailed picture of transition state structures, very little is known about the transition state structure for C-P bond cleavage. Although at present it is not clear which features of the active site geometry of PhnA facilitate efficient catalysis beyond electrostatic stabilization of the leaving group, a plausible explanation can be offered for the previously reported poor activity for phosphate ester hydrolysis (Kim, et al., 2011). AP has been shown to utilize strong electrostatic stabilization of the negative charge of the non-bridging oxygens by the binuclear Zn2+ cluster (Nikolic-Hughes, et al., 2005). On the basis of structures of AP with vanadate bound (PDB Code: 1B8J) (Holtz, et al., 1999), one of the non-bridging oxygens is believed to interact with both metals in the transition state (Figure 5B). On the other hand, the vanadate structure of PhnA is decidedly non-symmetric with the corresponding equatorial oxygen interacting much more strongly with M2 than with M1.

The formation of a stabilized acetate enolate dianion was also recently proposed for PnA hydrolysis by P. fluorescens PhnA based on structural and mechanistic studies (Kim, et al., 2011). In that study, stabilization of the enolate oxygens was proposed to be achieved by interactions with two conserved lysine residues (Lys126 and Lys128), rather than through stabilization by the M1 metal. This mechanistic proposal was based on modeling of the substrate according to the co-crystal structure of P. fluorescens PhnA with PnF. These two lysine residues are also conserved in S. meliloti PhnA (Lys130 and Lys132). However, in our structures these residues are far away from the ligands and are not involved in any binding interactions with these ligands. In order to test the importance of these residues in S. meliloti PhnA, we generated single Ala mutations at Lys130 and Lys132 and monitored the activity of these variants. Consistent with the observations with P. fluorescens PhnA (Kim, et al., 2011), mutation at either of these lysines in S. meliloti PhnA resulted in inactive enzyme (Table S1). The loss of activity need not imply a direct role of these residues in enolate stabilization and may also be due to secondary effects, such as detrimental changes in the solvent structure in the active site as observed for the N89V mutant. Although, we cannot at present rule out that these Lys residues do play a role in stabilization of the leaving group, we favor the model in Figure 5A for the following reasons. First, our mechanistic proposal for the role of the M1 metal in stabilizing the enolate oxygen is based on direct crystallographic observation of substrate PnA bound to the T68A mutant. Second, the orientiation of PnA bound to the T68A mutant is consistent with the geometric constraints of a predicted in-line displacement reaction whereas the orientation of PnF is not. The active sites of S. meliloti and P. fluorescens enzymes are very similar, but a few differences exist between the two enzymes, most notably the recombinant enzyme from S. meliloti, as isolated from E. coli, is monomeric, whereas the enzyme from P. fluorescens is a dimer (Kim, et al., 2011). Detailed mechanistic studies will be required to distinguish between the two strategies of enolate stabilization that have been proposed based on the available structural information.

SIGNIFICANCE

Bacteria have evolved the ability to metabolize phosphonates as a nutrient source for phosphorus, using chemistry that results in the cleavage of the inert C-P bond. The structural and biochemical studies presented here provide insights into the mechanism of C-P bond cleavage by S. meliloti PhnA, which represents a poorly studied activity within the catalytic repertoire of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. We show that PhnA bears an atypically spaced bimetallic center, and this larger inter-metal distance may be utilized to accommodate the distance between the entering nucleophile and the charge-bearing atoms of the leaving group in the transition state during C-P bond cleavage.

EXPERIMENTAL PRODUCEDURES

Materials, Culture conditions, and DNA manipulations

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Thermo Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) and were used without further purification. The purity of the commercially obtained PnA (Sigma-Aldrich) was verified by 1H NMR analysis and showed no acetate contamination (detection limit was less than 0.014 molar %). Media components were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific or VWR (West Chester, PA). The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2. Details of culture conditions and DNA manipulations are described in Supplemental Information.

Cloning, protein expression, purification, and crystallization

Cloning, expression, and purification of recombinant S. meliloti PhnA from E. coli has been described previously (Borisova, et al., 2011). For crystallization, the hexahistidine tag was removed by digestion with thrombin (1 unit/mg of protein) followed by purification using anion exchange (5 mL HiTrap Q-FF, GE Healthcare) and size exclusion chromatographies (Superdex 75 16/60, GE Healthcare). The purified recombinant protein was a monomer in solution as determined using analytical size exclusion chromatography. Apo protein at a final concentration of 20 mg/mL in 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5 buffer was used for sparse matrix crystallization screening trials, using the hanging drop vapor diffusion technique. Diffraction quality crystals were obtained in two mother liquor conditions at 9 °C, 25% PEG 3350, 0.2 M sodium chloride, 0.1 M Tris, pH 8.5 and 25% PEG 3350, 0.2 M ammonium acetate, 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.5. Crystals typically took three days to grow and were briefly soaked in mother liquor supplemented with 15% glycerol prior to vitrification in liquid nitrogen. PhnA mutants were generated using standard procedures for site directed mutagenesis and were expressed, purified, and crystallized according to the protocols for wild-type enzyme. The purity of all protein samples was greater than 95% as judged by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

The PhnA mutant T68A was incubated with 2 mM zinc chloride and 10 mM PnA for 2 h on ice prior to sparse screening for crystallization. Co-crystals of PhnA T68A mutant in complex with PnA were obtained in the crystallization condition 20% PEG 3350, 0.2 M ammonium chloride and briefly soaked in cryo protectant solution of mother liquor supplemented with 20% glycerol, 5 mM zinc chloride and 50 mM PnA prior to vitrification in liquid nitrogen. Co-crystals of the complex with PnF were obtained by soaking apo protein crystals in 10 mM of PnF in the mother liquor for 12 h. Metal ions were soaked by supplementing the mother liquor with 5 mM of zinc chloride, 5 mM manganese chloride, or 5 mM of iron(II) ammonium sulfate for 3 h. To generate the covalently bound vanadate complex, apo protein was incubated on ice for 10 min with 2 mM freshly boiled sodium orthovanadate solution and then crystallized in the manner described above.

PhnA enzyme kinetics

The formation of inorganic phosphate from PnA by the action of N-terminally hexahistidine tagged PhnA (PhnA-N-His) was detected by a discontinuous assay using a Malachite Green phosphate assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA). Assay mixtures (500 μL total volume) containing 50 mM HEPES-K (pH 7.5) and 0.42 μM PhnA-N-His were pre-incubated at 30 °C for 8 min and the reaction was initiated by the addition of PnA stock solutions to final concentrations of 0-400 μM. Aliquots of the reaction mixture (80 μL) were taken out every 20 s over a period of 2 min, quenched by addition to 20 μL of Malachite Green reagent prepared as per the manufacturer’s instruction, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min for color development. The assays were done in duplicate. The absorbance at 620 nm was plotted against the reaction time and the rate of A620 increase was converted to the rate of phosphate formation using a linear calibration curve prepared with known concentrations of inorganic phosphate standard (0-40 μM). The initial rates of phosphate formation were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation (V0=([S]*Vmax)/([S]+KM)) using the IGOR Pro 6.1 software package (WaveMetrics, Portland, OR) in order to determine steady state kinetic parameters of PhnA-N-His. The kinetics data are summarized in Table 2 and Figure S2.

To evaluate the divalent metal dependence of PhnA-N-His, 10 μM ZnCl2, MgCl2 × 6H2O, MnCl2 × 4H2O, CoCl2 × 6H2O, or (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 × 6H2O were added to the assay mixture prior to the pre-incubation period and assays were performed as described above. The concentrations of PhnA-N-His were adjusted (0.07-0.48 μM) to allow for the detection of product formation within the linear range of the assay. Assays in the presence of oxygen-sensitive Fe(II) were set up in an anaerobic chamber obtained from Coy Laboratory Products, Inc. (Grass Lake, MI) under an atmosphere of N2 and H2 (95%/%). The aliquots of buffer-enzyme solution containing Fe(II) were subsequently brought outside the glove box in tightly capped eppendorf tubes, followed by pre-incubation and reaction initiation with PnA as described above. The kinetics data are summarized in Table 2 and Figure S2.

Metal-free PhnA-N-His was prepared by treatment of the protein with 8.3 mM EDTA sodium salt at 4 °C for 3 h with gentle agitation followed by size exclusion chromatography using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NY) eluted with 50 mM HEPES-K, 0.2 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, pH 7.5. Following EDTA treatment, less than 0.02 Zn2+ ions per PhnA monomer were detected indicating nearly complete removal by EDTA treatment. The resulting apo PhnA-N-His was tested in the activity assay as described above with and without addition of Zn2+, Mn2+, or Fe2+ (Table 2 and Figure S2). When combinations of two divalent metal cations were studied (at 10 μM each) initial rates of product formation were measured at 200 μM PnA (Table S1, left).

PhnA exchanged into Chelex-treated buffer via a series of dilution-concentration steps to remove excess metal ions contained only 0.5 Zn2+ ions per monomer as determined using PAR assay (Hunt, et al., 1984, Okeley, et al., 2003). Because of the partial dissociation of the bound metal ions from PhnA during attempts to separate the protein from the constituents of the reconstitution buffer, the identity of the PhnA-bound metal ion(s) in PhnA reconstituted with different metals could not be characterized directly

Enzymatic activity of PhnA mutants purified as above but not treated with EDTA (at 10 μM, except for the T68A mutant at 5 μM) was measured as described above in the presence of 20 μM Mn2+ and 0.2 or 1.0 mM PnA (Table S1, right). The formation of Pi was monitored over a period of 0.5-1 h.

Phasing and structure determination

A ten-fold redundant data set was collected from crystals of S. meliloti PhnA to a limiting resolution of 1.35 Ǻ (overall Rmerge = 0.068, I/σ(I) = 1.8 in the highest resolution shell) utilizing a Mar 300 CCD detector (LS-CAT, Sector 21 ID-D, Advanced Photon Source, Argonne, IL). The structure of PhnA was solved by single wavelength anomalous diffraction utilizing anomalous scattering from a mercury derivative (six-fold redundancy with Rmerge = 0.084, I/σ(I) = 3.2 in the highest resolution shell). Data were indexed and scaled using the HKL-2000 package (Otwinowski, et al., 2003). Mercury sites were identified using HySS and the heavy atom substructure was imported to SHARP for maximum likelihood refinement and phase calculation, yielding an initial figure of merit of 0.497 to 1.9 Ǻ resolution. Solvent flattening using DM further improved the quality of the initial map and most of the main chain could be built using ARP/wARP (Perrakis, et al., 1997). Cross-validation used 5% of the data in the calculation of the free R factor (Kleywegt and Brunger, 1996). The remainder of the model was fitted using XtalView and further improved by rounds of refinement with REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 1997; Murshudov et al., 1999) interspersed with rounds of manual building using XtalView (McRee, 1999).

The co-crystal structures of PhnA with PnA, acetate, phosphonoformate, and vanadate were determined, to resolutions of 2.1 Å, 2.0 Å, 1.6 Å, and 1.8 Å, respectively, by molecular replacement using the coordinates of native PhnA as a search probe. Each of the structures was refined and validated using the procedures detailed above. Cross-validation was routinely used throughout the course of model building and refinement using 5% of the data in the calculation of the free R factor. For each of the structures, the stereochemistry of the model was monitored throughout the course of refinement using PROCHECK (Laskowski, et al., 1996). Relevant data collection and refinement statistics are provided in Table 1.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

PhnA is homologous to alkaline phosphatases but hydrolyzes a carbon-phosphorus bond

The PhnA active site can utilize different metal ions for catalysis

Crystal structures of PhnA with substrate, product, inhibitor, and a transition state mimic

A mechanism for C-P bond cleavage by PhnA is proposed

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM PO1 GM077596) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS, NIH, or HHMI. We thank Drs. Keith Brister, Spencer Anderson, and Joseph Brunzelle at LS-CAT (23-ID at Argonne National Labs, APS) for facilitating crystallographic data collection. We thank Prof. John Gerlt for his critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Borisova SA, Christman HD, Mourey-Metcalf ME, Zulkepli NA, Zhang JK, van der Donk WA, Metcalf WW. Genetic and biochemical characterization of a pathway for the degradation of 2-aminoethylphosphonate in Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22283–22290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LL, Ingall ED, Benner R. Marine organic phosphorus cycling: Novel insights from nuclear magnetic resonance. American Journal of Science. 1999;299:724–737. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JE. Structure and mechanism of alkaline phosphatase. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:441–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlani G, Klimek-Ochab M, Jaworski J, Lejczak B, Picco AM. Phosphonoacetic acid utilization by fungal isolates: occurrence and properties of a phosphonoacetate hydrolase in some penicillia. Mycol Res. 2006;110:1455–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Bairoch A, Koonin EV. A superfamily of metalloenzymes unifies phosphopentomutase and cofactor-independent phosphoglycerate mutase with alkaline phosphatases and sulfatases. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1829–1835. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt JA, Babbitt PC, Rayment I. Divergent evolution in the enolase superfamily: the interplay of mechanism and specificity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz KM, Stec B, Kantrowitz ER. A model of the transition state in the alkaline phosphatase reaction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8351–8354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz KM, Stec B, Myers JK, Antonelli SM, Widlanski TS, Kantrowitz ER. Alternate modes of binding in two crystal structures of alkaline phosphatase-inhibitor complexes. Protein Sci. 2000;9:907–915. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.5.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JB, Neece SH, Schachman HK, Ginsburg A. Mercurial-promoted Zn2+ release from Escherichia coli aspartate transcarbamoylase. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14793–14803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallarakal AT, Mitra B, Kozarich JW, Gerlt JA, Clifton JG, Petsko GA, Kenyon GL. Mechanism of the reaction catalyzed by mandelate racemase: structure and mechanistic properties of the K166R mutant. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2788–2797. doi: 10.1021/bi00009a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A, Benning MM, Oklee S, Quinn J, Martin BM, Holden HM, Dunaway-Mariano D. Divergence of chemical function in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily: structure and mechanism of the p-C bond cleaving enzyme phosphonoacetate hydrolase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:3481–3494. doi: 10.1021/bi200165h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EE, Wyckoff HW. Reaction mechanism of alkaline phosphatase based on crystal structures. Two-metal ion catalysis. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:449–464. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90724-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ, Brunger AT. Checking your imagination: applications of the free R value. Structure. 1996;4:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononova SV, Nesmeyanova MA. Phosphonates and their degradation by microorganisms. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;67:184–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1014409929875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulakova AN, Kulakov LA, Quinn JP. Cloning of the phosphonoacetate hydrolase gene from Pseudomonas fluorescens 23F encoding a new type of carbon-phosphorus bond cleaving enzyme and its expression in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas putida. Gene. 1997;195:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassila JK, Herschlag D. Promiscuous sulfatase activity and thio-effects in a phosphodiesterase of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12853–12859. doi: 10.1021/bi801488c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JW, Wisdom GB, McMullan G, Larkin MJ, Quinn JP. The purification and properties of phosphonoacetate hydrolase, a novel carbon-phosphorus bond-cleavage enzyme from Pseudomonas fluorescens 23F. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.225_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullan G, Harrington F, Quinn JP. Metabolism of phosphonoacetate as the sole carbon and phosphorus source by an environmental bacterial isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1364–1366. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1364-1366.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee DE. XtalView/Xfit--A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J Struct Biol. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf WW, van der Donk WA. Biosynthesis of phosphonic and phosphinic acid natural products. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:65–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.091707.100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolic-Hughes I, O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Alkaline phosphatase catalysis is ultrasensitive to charge sequestered between the active site zinc ions. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9314–9315. doi: 10.1021/ja051603j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Alkaline phosphatase revisited: hydrolysis of alkyl phosphates. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3207–3225. doi: 10.1021/bi012166y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeley NM, Paul M, Stasser JP, Blackburn N, van der Donk WA. SpaC and NisC, the cyclases involved in subtilin and nisin biosynthesis, are zinc proteins. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13613–13624. doi: 10.1021/bi0354942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Borek D, Majewski W, Minor W. Multiparametric scaling of diffraction intensities. Acta Crystallogr A. 2003;59:228–234. doi: 10.1107/s0108767303005488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten CE, O’Halloran TV. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science. 2001;292:2488–2492. doi: 10.1126/science.1060331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panas P, Ternan NG, Dooley JS, McMullan G. Detection of phosphonoacetate degradation and phnA genes in soil bacteria from distinct geographical origins suggest its possible biogenic origin. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:939–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Sixma TK, Wilson KS, Lamzin VS. wARP: improvement and extension of crystallographic phases by weighted averaging of multiple-refined dummy atomic models. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:448–455. doi: 10.1107/S0907444997005696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard JP, Amyes TL. Proton transfer at carbon. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:626–633. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(01)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S, Burdett H, Temperton B, Wick R, Snelling D, McGrath JW, Quinn JP, Munn C, Gilbert JA. Evidence for phosphonate usage in the coral holobiont. ISME J. 2010;4:459–461. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wackett LP, Shames SL, Venditti CP, Walsh CT. Bacterial carbon-phosphorus lyase: products, rates, and regulation of phosphonic and phosphinic acid metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:710–717. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.710-717.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski CL, Cardia JP, Kantrowitz ER. Alkaline phosphatase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium T. maritima requires cobalt for activity. Protein Sci. 2002;11:903–911. doi: 10.1110/ps.4260102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski CL, Kantrowitz ER. Altering of the metal specificity of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50476–50481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalatan JG, Fenn TD, Brunger AT, Herschlag D. Structural and functional comparisons of nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase and alkaline phosphatase: implications for mechanism and evolution. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9788–9803. doi: 10.1021/bi060847t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalatan JG, Fenn TD, Herschlag D. Comparative enzymology in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily to determine the catalytic role of an active-site metal ion. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:1174–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalatan JG, Herschlag D. Alkaline phosphatase mono- and diesterase reactions: comparative transition state analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1293–1303. doi: 10.1021/ja056528r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalatan JG, Catrina I, Mitchell R, Grzyska PK, O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D, Hengge AC. Kinetic isotope effects for alkaline phosphatase reactions: implications for the role of active-site metal ions in catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9789–9798. doi: 10.1021/ja072196+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.