Abstract

Associations between early deprivation and memory functioning were examined in 9- to 11-year-old children. Children who had experienced prolonged institutional care prior to adoption were compared to children who were adopted early from foster care and children reared in birth families. Measures included the Paired Associates Learning task from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test and Automated Battery (CANTAB) and a continuous recognition memory task during which ERPs were also recorded. Children who experienced prolonged institutionalization showed deficits in both behavioral memory measures as well as an attenuated P300 parietal memory effect. Results implicate memory function as one of the domains that may be negatively influenced by early deprivation in the form of institutional care.

Keywords: neurodevelopment, memory functioning, ERP, post-institutionalized children, international adoption

Examination of the effects of deprivation and neglect early in development on later social, emotional and cognitive functioning is of practical and theoretical importance. It is estimated that millions of children worldwide live under institutional care conditions that are deficient in the motor, cognitive, linguistic and social stimulation needed to support typical development. Some of these children are subsequently adopted or fostered into generally supportive and stimulating family environments. Examining their functioning following removal from institutional care can provide insight into the impact of early deprivation on neurobehavioral development. It can also provide the impetus to intervene to improve conditions for children without permanent parents worldwide.

Numerous studies have shown that institutionalized children exhibit delays in physical (Johnson, 2001) and socioemotional development (Gunnar, 2001; Nelson et al., 2007; Maclean, 2003), along with poorer scholastic achievement especially for children experiencing longer periods of early deprived care (Beckett et al., 2006; van IJzendoorn, Juffer, & Poelhuis, 2005). Until recently, relatively little research on the sequelae of early institutional care has focused on specific cognitive functions and neurophysiological correlates of these cognitive processes. However, at least two recent studies (Bos, Fox, Zeanah, & Nelson, 2009; Pollak et al., 2010) have begun to address specific aspects of executive function and memory. While impairments were noted in multiple domains, both studies have noted deficits in memory performance. Pollak et al. (2010) included a comprehensive battery of cognitive tasks to examine neurodevelopmental effects of early deprivation at 8 years of age. In their sample, post-institutionalized children with mean age at adoption of approximately two years showed deficits in spatial working memory, paired associates learning (a test of visual memory and new learning), and memory for faces compared to both non-adopted children and children adopted early from foster care (Pollak et al., 2010). In addition, among the post-institutionalized group of children, duration of institutional care was negatively associated with performance on paired associates learning and narrative memory. Bos et al. (2009) reported that at age 8 years, compared to never-institutionalized controls, children who had ever spent time in an institution during their first few years of life had poorer performance on a delayed match to sample task, which is a forced-choice pattern recognition test that is thought to rely on medial temporal lobe (MTL) function.

While both of these studies indicate deficits or delays in memory functions, the tasks showing impairments were not designed to explicitly assess functioning of medial temporal lobe brain structures. This was the purpose of the present study; specifically to examine relations between prior institutional care and functioning on a task dependent on structures in the medial temporal lobe. Item recognition memory is largely dependent on the medial temporal lobe and midline diencephalic structures, such as the hippocampus (see Eichenbaum, Yonelinas, & Ranganath, 2007, for review). The role of medial temporal lobe in recognition memory has been corroborated in a number of functional MRI studies in adults (Dobbins & Davachi, 2006; Henson, 2005) and in children (Ghetti, DeMaster, Yonelinas, & Bunge, 2010; Menon, Boyett-Anderson, & Reiss, 2005; Ofen et al., 2007; Richmond & Nelson, 2007).

There are a number of reasons that children reared in institutions during infancy and early childhood might exhibit deficits on MTL-mediated tasks. The most critical reason is evidence that deprived or disordered care early in life threatens the infant’s viability and activates stress-sensitive neurobiological systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis production of cortisol and extra-hypothalamic production of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (Korosi & Baram, 2010; McEwen, 2007, for reviews). Chronic activation of these stress mediators has been shown in animal studies to impair functioning of the hippocampus (e.g., Ivy et al, 2010). In several studies, infants and young children reared in institutions that provide poor physical and socioemotional care have been shown to exhibit patterns of cortisol production consistent with chronic stress both while in the institution (Carlson & Earls, 1997; Dobrova-Krol, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Cyr, & Juffer, 2008) and, in some cases, years following adoption (Gunnar, Morison, Chisholm, & Schuder, 2001; Kertes, Gunnar, Madsen, & Long, 2008; Wismer Fries, Shirtcliff, & Pollak, 2008).

There have been only a few studies of brain activity in post-institutionalized children, and none that has examined brain function during a memory task. However, evidence that temporal lobe dysfunction might be present after early deprivation comes from a positron emission topography study by Chugani et al. (2001), which indicated that 7- to-11-year-old children adopted from Romanian orphanages had reduced glucose metabolism in the medial temporal lobe structures and inferior temporal cortex. In a diffusion tensor imaging study, differences between socially deprived orphans and controls were found in the integrity of the left uncinate fasciculus, a white matter tract that connects the anterior temporal lobe to the frontal lobe (Eluvathingal et al., 2006). One study using MRI in post-institutionalized children and controls noted differences in amygdala volume; however, not in hippocampal volume (Tottenham et al., 2010).

In the present study, we chose event-related potentials (ERP) as our method of investigation into the neurophysiology of memory functioning in post-institutionalized children. ERPs measure changes in brain electrical activity time locked to presentation of specific stimuli and are recorded from electrodes placed on the scalp. Several ERP studies also found that early deprivation affects neural correlates of recognition of faces and facial expressions of emotion (Moulson, Westerlund, Fox, Zeanah, & Nelson, 2009; Parker & Nelson, 2005a, 2005b). However, to date, there are no published ERP studies of memory function with a focus on effects of early institutional deprivation.

ERPs have proven useful in examining neural activity associated with memory functioning. A common method to analyze ERP data in conjunction with recognition memory in the adult literature has been to compare ERPs elicited to stimuli correctly recognized as old or previously seen (hits) to stimuli that are correctly judged to be new or never seen (correct rejections). It has consistently been shown in the adult literature with both verbal and pictorial stimuli that this comparison results in a more positive deflection to old compared to new items maximal over the parietal region around 300–400 msec after stimulus onset with a duration of 400–500 msec (Friedman, 1990; Rugg & Nagy, 1989; Wilding & Rugg, 1996). Thus, the parietal P300 (also called P3b) ERP component is commonly used to index this old/new effect. This old/new effect (also termed the episodic memory effect) is thought to be correlated with medial temporal lobe activity. Notably, this episodic memory effect is reduced in the case of bilateral hippocampal lesions through temporal lobectomy (Johnson, 1995; Nelson, Collins & Torres, 1991; Rugg, Roberts, Potter, Pickles, & Nagy, 1991; Smith & Halgren, 1989; Wegesin & Nelson, 2000). In addition, several studies on recognition memory have identified an early (300–500 msec) negative-going midfrontal ERP component that is more positive for old compared to new items. This component is often referred to as the FN400 (see Rugg & Curran, 2007, for a review). From the perspective of the dual-process model of recognition, these two components, the P300 and FN400, have been interpreted as indexing processes of recollection and familiarity, respectively. Whereas recollection refers to retrieval of qualitative details of an episode/item, familiarity processes are fast-acting and context-free (Yonelinas, 2002).

Although ERPs have been successfully recorded to study recognition memory in infants (e.g., Bauer, Wiebe, Carver, Waters, & Nelson, 2003; Bauer et al., 2006; Carver, Bauer, & Nelson, 2000; Nelson, Thomas, de Haan, & Wewerka, 1998), there have been relatively few such studies in preschool and school age children. However, the extant studies suggest that the parietal old/new effect can also be seen in children, though amplitudes and/or time windows are often different than those seen in adults. In one study that compared ERPs in 4-year-olds and adults during a recognition paradigm, 4-year-olds did show an old/new effect but it was seen 400–500 msec later than that of adults (Marshall, Drummey, Fox, & Newcombe, 2002). In Berman, Friedman, and Cramer (1990) and Berman and Friedman (1993), a P300 old/new effect was observed in response to both words and line-drawings in 7- to 10-year-old children, 14- to 16-year-old adolescents and adults that was highly similar across the age groups. Similarly, both the 10-year-old and the 12-year-old group showed a P300 old/new effect during item memory for line-drawings that was similar to adults in Cycowicz, Friedman, and Duff (2003). In Czernochowski, Mecklinger, and Johansson (2005), for both the younger children (ages 6–8 years) and the older children (ages 10–12 years), the old/new effect was most evident at parietal electrodes between 700–800 stimulus onset which was later than that found in their young adult group. In summary, these studies provide strong support for the existence of a parietal ERP component that indexes correct recognition in children.

Several studies also examined the ERP component associated with familiarity processes in children, yielding inconsistent findings. Whereas Mecklinger et al. (2010) found evidence for ERP correlates of familiarity, Czernochowki et al. (2005) failed to find a midfrontal effect in children. In Hepworth et al. (2001) and in Czernochowski, Mecklinger, Johansson, and Brinkmann (2009), a frontal old/new effect was observed but in the opposite direction than observed in adults (more positive for new than old). A recent study by Van Strien et al. (2011) reported differences in frontal N2 and N400 amplitudes to New/Old stimuli in a continuous face recognition paradigm in 8–9 year olds (but not in 11–12 year olds), and no P300 effects of New/Old.

The goal of the present study was to investigate further and characterize the memory deficit observed in post-institutionalized children by Pollak et al. (2010) and Bos et al. (2009). To this end, we tested three groups of children on two behavioral measures of memory, the Paired Associate Learning task, to determine if we could replicate the previous Pollak et al. (2010) findings, and a continuous recognition memory (CRM) task. ERPs were recorded while the children were engaged in the CRM task. The continuous recognition memory task has been shown to activate the hippocampus in previous fMRI studies in adults (Brozinsky et al. 2005; Johnson, Muftuler, & Rugg, 2008). General intelligence was also measured and included as a covariate because past research has shown IQ to be negatively impacted in this population (see van IJzendoorn, Luijk, & Juffer, 2008, for a recent meta-analysis).

In order to examine the electrophysiological correlates of memory function, we focused primarily on the parietal P300 component due to prior literature on the impairments in medial temporal lobe function associated with exposure to chronic stress and high levels of circulating glucocorticoids, as discussed above. We also examined hemispheric differences given mixed reports regarding the laterality of the old/new effect in the literature. Schloerscheidt and Rugg (1997) reported a left lateralized parietal old/new effect regardless of stimulus type. This finding has been replicated in children using pictorial stimuli by Cycowicz et al. (2003), Czernochowski et al. (2005), and Czernochowski et al. (2009). However, in one study with 4-year-old children (Marshall et al., 2002), the old/new effect was stronger on the right. Hepworth, Rovet, and Taylor (2001) also showed a right lateralized old/new effect in their sample of 11- to 14-year-olds children, although the effect was localized frontally.

Given suggestions in the literature that some post-institutionalized children might also show deficits in executive functioning/attention skills which could contribute to poorer memory performance (Bos et al., 2009; Colvert et al., 2008; Kreppner et al., 2001; Pollak et al., 2010), we also examined classic attention related components such as N1, P2 and N2. The N1 component has been shown to be influenced by visual-spatial attention (Hillyard, Vogel, & Luck, 1998), the N2 component has been tied to novelty detection, attention to novelty and infrequent stimuli (Näätänen & Picton, 1986), and the P2 component has been shown to be sensitive to task relevancy and target frequency (Luck & Hillyard, 1994). Similar components have been used in the developmental literature to index attentional processes (Nelson & McCleery, 2008; Nelson & Monk, 2001). The time window of the N2 component may overlap with the FN400 component and therefore, also may index familiarity processes of recognition, if a memory (old/new) effect were found.

The present sample consisted of a post-institutionalized (PI) group and two comparison groups, both of which were roughly comparable on parent education and incomes to the PI group. The early-adopted (EA/FC) comparison group consisted of internationally adopted children who had experienced primarily family-type care prior to adoption (i.e., foster care). The non-adopted (NA) comparison group consisted of children who were born and raised in their birth families. The EA/FC comparison group was chosen to control for adverse early life experiences that might be common to internationally adopted children (e.g., presence of early life relationship disruption, poor prenatal care, poverty, transitions in care). We predicted that the PI group would show disruptions in memory functioning on both behavioral and neurophysiologic indices compared to both the EA/FC and NA groups. We also predicted that performance of the EA/FC group would fall between the levels of the PI and NA groups.

Method

Participants

Participants were 87 children ages 9–11 years (42 females) who fit into one of following three groups: post-institutionalized children (PI), early adopted/foster care children (EA/FC), or non-adopted children (NA). PI children were 12 months or older at adoption, having spent 75% of the pre-adoptive life in an orphanage or other institution. EA/FC children were 8 months or younger at adoption, having spent less than 2 months of their pre-adoptive life in any institution. NA children were born and raised in families in the United States whose education and incomes were comparable to those of families who adopt internationally. Sample characteristics by group can be seen in Table 1. Children in both adoptive groups were in their adoptive homes at least 4 years prior to testing. PI children were adopted predominately from Eastern Europe (63.3%) and Asia (33.3%), while EA/FC children were adopted primarily from SE Asia (57.1%) and Latin/South America (39.3%). The majority of participants were right-handed (2 PI, 2 EA/FC and 1 NA were left-handed).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Group

| Post-institutionalized (PI) n = 30 |

Early Adopted from Foster Care (EA/FC) n = 28 |

Non-adopted (NA) n = 29 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% female) | 50% | 46.4% | 48.3% |

| Mean age (years) at testing | 9.73 (SD =.79) | 9.96 (SD = .74) | 9.76 (SD = .74) |

| Mean number of years in adoptive home | 7.59 (SD = 1.5) | 9.56 (SD = .8) | Not applicable |

| Mean years of parent education | 16.33 (SD = 2.22) | 16.44 (SD = 2.08) | 15.87 (SD = 1.84) |

| Median family income | 75–100K | 75–100K | 100–125K |

Recruitment and Screening

The internationally adopted participants in this study were drawn from a large Minnesota registry of families of internationally-adopted children who were interested in participating in research. Children on this registry account for about 60% of all children adopted internationally into the state. Parents who agree to join this registry tend to be more highly educated than those who refuse (Hellerstedt et al., 2008). The participants in the present study were recruited from a subsample of this registry that completed an initial developmental assessment at study intake (details reported in Loman, Wiik, Frenn, Pollak, & Gunnar, 2009). Participants were screened for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, and children with facial features consistent with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome were not recruited for this study (for procedures, see Loman et al., 2009). The non-adopted children were recruited from a registry of families who indicated interest in participating in child development research soon after the child’s birth. Roughly 90% of the internationally-adopted children’s parents agreed to study participation once contacted by phone, while only about 50% of the non-adopted children’s parents consented.

Procedures

Children attended a 1.5-hour laboratory session accompanied by a parent. After written parental consent and child assent were obtained, two memory tasks, Paired Associates Learning (PAL) and continuous recognition memory (CRM), were administered. The order of task presentation was counterbalanced across groups. The sensor net used during the CRM task was fitted prior to the start of this task and removed following it.

Paired Associates Learning (PAL)

Children completed the Paired Associates Learning (PAL) task from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB, Cambridge Cognition, 2004). This task measures visual processing and learning. Eight boxes on the screen open in random order, each revealing a different abstract visual stimulus. The number of boxes that contain a stimulus increases from one to six across levels. After all the boxes are revealed, each stimulus is successively displayed in the middle of the screen and children are instructed to touch the box where the stimulus originally appeared. The task becomes progressively more difficult across trials, and trials are repeated if the child makes an error, until the child successfully completes the trial. The limit for repeated testing was 10 trials. Total Errors was used as the outcome measure.

Continuous Recognition Memory (CRM)

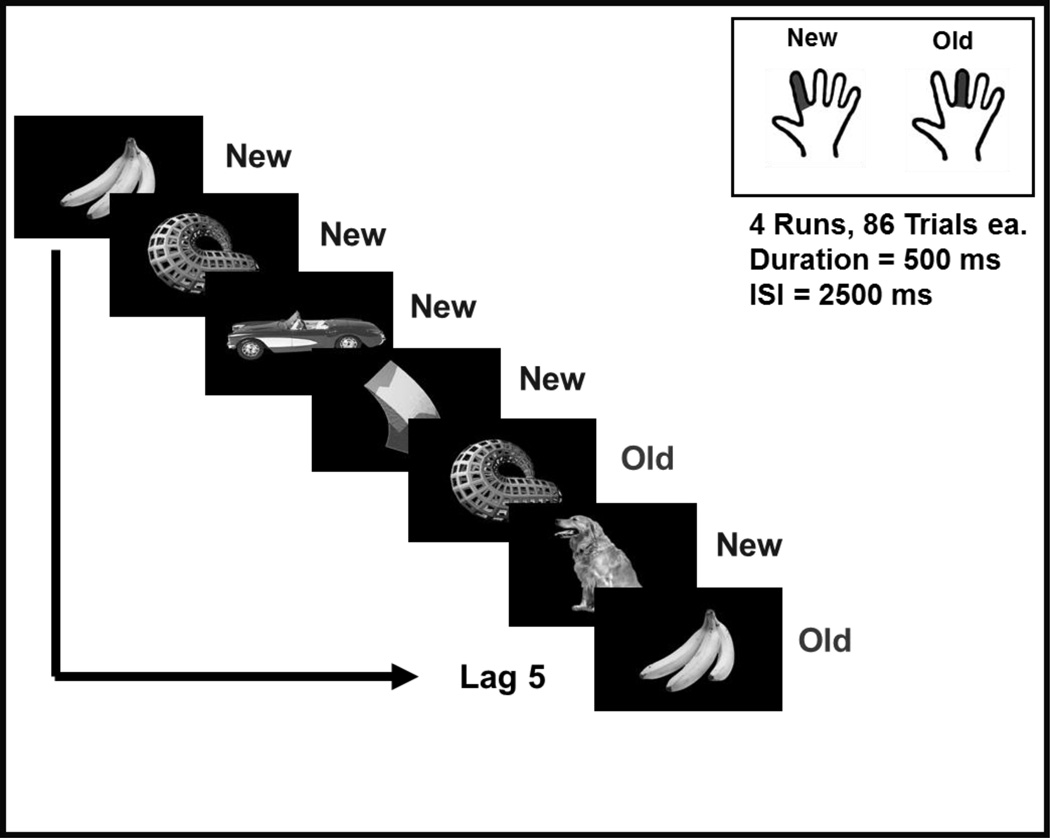

Participants saw a series of pictorial stimuli that were presented twice with varying numbers of intervening stimuli (see Figure 1). The stimuli consisted of 184 color photographs of everyday objects (e.g., car, banana) and 3-dimensional abstract sculpture-like objects. The stimuli were presented using E-Prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA).

Figure 1.

The continuous recognition memory task. Inset: Participant response instructions to new and old stimuli.

The data were collected in 4 runs of 86 trials, each of which lasted 4 min.18 sec. Each run consisted of 40 items that were presented twice with 1–15 intervening stimuli, and 6 items that never repeated (included as distractors to prevent anticipation). Stimulus duration was 500 msec, and was followed by an inter-stimulus interval of 2500 msec consisting of a red cross on a black screen. The stimulus order within a run was kept the same across participants while the order of runs was randomized for each participant.

Participants were instructed to position their right index and middle fingers on two buttons of a button response box, and to press one button with their index finger when they viewed a picture for the first time (“New”) and another button with their middle finger if the same picture appeared for the second time (“Old”). Responses made at any time within the 3000-msec trial were recorded. Accuracy and reaction time were recorded and analyzed. Prior to placement of the electrode net, participants underwent two practice rounds with a different set of stimuli in order to ensure task comprehension. A practice run consisted of 15 items that repeated after 1–5 intervening items, as well as 3 distractor items that did not repeat. At the end of this practice run, if the mean accuracy was below 70%, the participant completed a second practice run with a different set of pictures.

Intellectual Quotient (IQ)

IQ was estimated using the Block Design and Vocabulary subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – 3rd Edition (WISC-III). These two subtests correlate highly with Full Scale Intelligence Quotient, thus a full-scale score was approximated.

ERP Data Collection and Processing

ERPs were recorded during the CRM task using Net Station 4.2.3. Electrophysiological data were acquired using a 128-electrode array (128-Channel HydroCel Geodesic Sensor Net, Electrical Geodesics Inc.) following procedures described in the Geodesic Sensor Net technical manual (Electrical Geodesics, 2007). Recorded data were initially processed in Net Station 4.2.3. This multi-step procedure included filtering with a 0.3–30 Hz bandpass, segmentation (each epoch spanned 100 ms pre-stimulus and 1500 ms post-stimulus), and bad channel replacement (the automated procedure imputed channels with more than 200 µV difference between maximum and minimum signal for more than 20% of the recording). Correct trials were identified and raw data files for these trials were exported to EEGLAB operating under MATLAB (Delorme & Makeig, 2004). Each file was visually inspected and trials with extreme, paroxysmal noise were manually rejected. Trials were not excluded if they contained smaller-scale noise (e.g., eye blinks).

The EEGLAB Independent Component Analysis algorithm (Makeig, Debener, Onton, & Delorme, 2004) was used to extract activity components, with the goal of subtracting eye artifact components from the data. Subjects with fewer than 102 trials were excluded from the ICA analysis. This threshold was determined based on the sampling rate and ICA matrix size1. Given the wide variability in eye blinks in children and this sample in particular, imposing this stringent number of minimum data points to estimate each ICA weight was deemed necessary to allow for stable and clearly defined eye blink components. For those subjects who met this criterion, a PCA reduction to 64 components was superimposed on the ICA algorithm in order to allow for a minimum of 10 data points per ICA matrix weight. The CorrMap procedure developed by Debener and colleagues (Viola et al., 2009) was then used to identify a maximum of 3 components that were highly correlated with a prototypical eye blink template chosen from one of the subjects. Visual inspection was also used to identify a maximum of two additional components that resembled the eye blink template. These components were marked for rejection and subtracted from the data. Once this artifact correction method was implemented, all trials were visually inspected again and any trials that were still artifact-contaminated were deleted manually. The Cz channel was then recovered, and all data were re-referenced to an average reference that excluded eye channels. Finally, the data were baseline-corrected using a 100 ms pre-stimulus window.

All subsequent pre-processing was conducted using the Psychophysiology Toolbox for MATLAB (Bernat, Williams, & Gehring, 2005). Scripts for trial extraction and averaging were used to compute averages for subject, trial type, and grand averages. In order to ensure a comparable number of trials for each condition across participants, 42–60 trials in each of the Old/New categories were randomly retained for each participant. To ensure no artificial group differences were created by allowing radically different numbers of trials in mean amplitude calculations, trials were randomly deleted for participants who had more than 60 because past research has shown that increasing the number of trials makes waveforms smoother and mean amplitudes smaller (Thomas, Grice, Najm-Briscoe, & Miller, 2004).

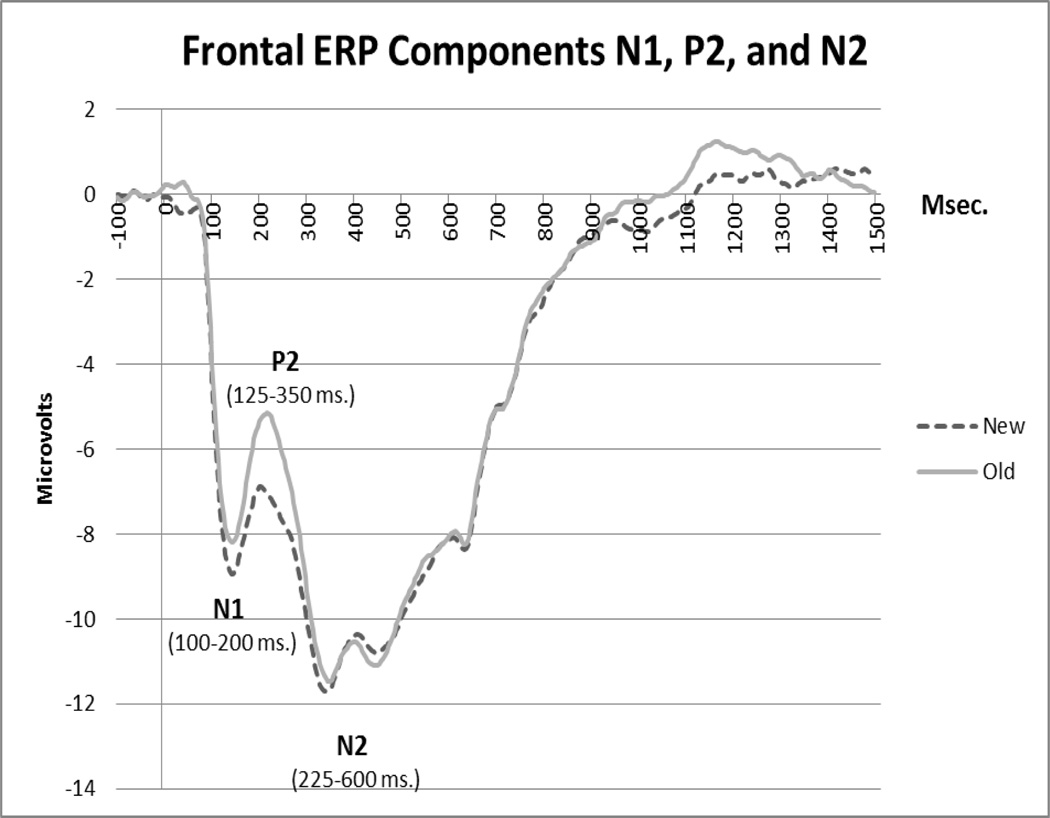

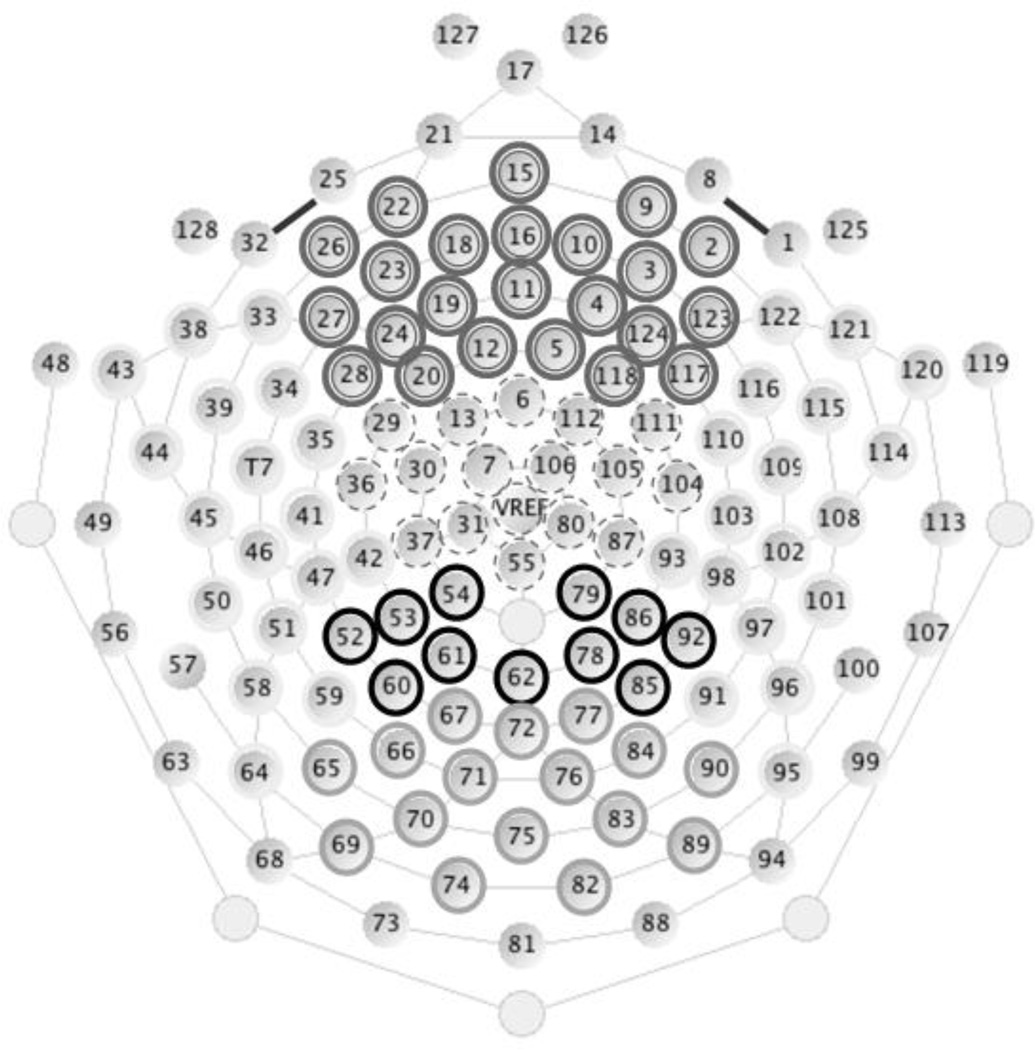

We investigated the P300 memory ERP component over parietal scalp (400–1000 ms), as well as N1 (100–200 ms), P2 (125–350 ms) and N2 (225–600 ms) components over frontal scalp locations (see Figure 2). ERP components were defined by subtracting the median value in the 100 ms baseline from each data point in the post-baseline period and extracting peak and mean amplitude values for each component. A lowpass filter of 20 Hz was applied to the data before the extraction of component means and before graphic display of waveforms in order to smooth the ERP components. Regions of interest were defined based on correspondences between the electrode net configuration and known anatomical regions, while the boundaries between regions were chosen using visual inspection in order to minimize the heterogeneity of ERP components within a region. Electrodes on the outer rim and eye electrodes were excluded from analysis. The specific electrodes included in the frontal (marked in gray) and the parietal (marked in black) regions are presented in Figure 3. Left/right regions were computed by excluding electrodes on the midline (in those analyses, midline electrodes were also excluded from computations of new/old variables). For all ERP components, mean amplitude was used as the dependent measure as some components had clearly defined and unique peaks while others did not. Analyses of peak amplitude produced similar results to mean amplitude in every instance when unique and identifiable peaks were present.

Figure 2.

Frontal components N1, P2 and N2.

Figure 3.

Regions of interest. Frontal electrodes are outlined in double gray circles and parietal electrodes are outlined in continuous black circles.

Results

Missing Data

All 87 children completed the PAL task. Two PI children refused to perform the CRM task. Participants were excluded from the CRM analyses if they had an overall accuracy below 60% (6 PI, 3 EA/FC, and 1 NA). Thus, a total of 75 participants were retained for CRM behavioral analyses (22 PI, 25 EA/FC, 28 NA). After ERP preprocessing, 54 participants were retained for further ERP analyses (16 PI, 18 EA/FC, 20 NA). Of the 21 participants without clean ERP data, 4 participants were excluded due to excessive movement artifacts leading to less than 102 noise-free trials before ICA processing (2 PI, 1 EA/FC, 1 NA), 16 participants were excluded post-ICA due to persistent eye blink or eye movement artifacts, leading to the manual deletion of remaining noisy trials and less than 40 trials remaining in each New/Old category (4 PI, 6 EA/FC, 6 NA). One additional participant (NA) was excluded due to technical problems during data collection.

Performance on the PAL task did not differ between children who were excluded from analyses due to poor performance on the CRM task (n = 12) and those who were included (n = 75). Among the 75 children who completed the behavioral portion of the CRM task with adequate performance, those excluded during ERP processing (n = 21) tended to perform worse than those retained (n = 54) on overall CRM accuracy (t(73) = −1.87, p = .07) as well on PAL total errors (t(73) = 1.91, p = .06). There were no significant differences in gender ratios or age between the participants excluded from analyses and those retained.

Data Analysis Plan

The behavioral data were analyzed first for the whole group (n = 75 for CRM task; n = 87 for PAL task) and then for the subset with usable ERP data (n = 54). For the continuous recognition memory accuracy and reaction time measures, we conducted a 2 (trial type: new, old)×3 (group: PI, EA/FC, NA) repeated measures analysis using a general linear model (GLM) with trial type as a within-subject variable and group as a between-subjects variable2. For the Paired-Associate Learning task, a one-way GLM was conducted to test for group differences using total errors as the dependent variable. Tukey HSD post-hoc tests were used to examine main effects of group when present. For the ERP analyses, hemisphere (left/right) was included as a repeated measure given suggestions in the literature of hemispheric differences in recognition memory (see Introduction). For measures correlated with IQ, we recalculated results controlling for IQ and report differences in findings with and without IQ as a covariate. Finally, in addition to the GLM analyses, we also conducted correlations between ERP measures and CRM behavioral measures in order to further explore the neural correlates of success on this task.

Behavioral Performance

Paired Associates Learning

For the full sample, significant effects of group were noted for total errors, F(2, 84) = 5.18, p = .008, η2p = .11. Group means are displayed in Table 2. Post-hoc tests revealed that the PI group scored below both the NA group (p = .007) and the EA group (p = .07). The EA/FC and NA groups did not differ significantly on this measure. The above analysis was repeated for the sample of children that was included in the ERP analyses (n = 54). In this case, with the reduced degrees of freedom, the omnibus group effect was observed only at the trend level (F(2, 51) = 2.06, p = .14, η2p = .08). Because IQ correlated with PAL scores, r(87) = −.26, p = .014, the full sample analysis was repeated covarying IQ, resulting in a reduction in significance to a trend level, F(2, 83) = 2.78, p =.068.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Behavioral Performance on the CRM and PAL tasks by Group for the Whole Sample and for the ERP Subsample in Parentheses

| Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-institutionalized |

Early-Adopted Controls |

Non-Adopted Controls |

||||

| Measures | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| CRM Task Accuracy a | ||||||

| NEW | 85.05 (85.19) |

11.94 (12.61) |

91.24 (93.50) |

7.57 (5.35) |

92.86 (94.00) |

7.49 (5.74) |

| OLD | 82.68 (82.13) |

10.26 (11.55) |

86.24 (91.00) |

12.31 (5.88) |

90.07 (90.05) |

8.07 (8.84) |

| CRM Task Reaction Time b | ||||||

| NEW | 1014.03 (959.92) |

257.09 (272.34) |

1083.15 (1082.05) |

212.44 (224.33) |

1120.06 (1111.11) |

197.96 (210.08) |

| OLD | 978.86 (922.07) |

242.38 (251.77) |

1045.77 (1052.75) |

167.44 (175.26) |

1103.56 (1078.92) |

179.39 (181.18) |

| Paired Associates Learning c | ||||||

| Total Errors | 11.47 (10.31) |

7.92 (9.61) |

7.61 (6.89) |

6.82 (7.19) |

6.17 (5.55) |

4.31 (4.15) |

Note. CRM = Continuous Recognition Memory;

Accuracy scores are in percentages;

Reaction Time data are in milliseconds;

CANTAB subtest

Continuous Recognition Memory

Accuracy

There was a significant main effect of trial type, F(1, 72) = 14.43, p < .001, η2p = .17, such that children were more accurate in identifying new items than old. The effect of group was also significant, (F(2, 72) = 4.55, p = .014, η2p = .11), but the interaction of trial type and group was not significant, F(2, 72) = .83, ns. Post-hoc tests indicated that the PI group was less accurate than the NA group (p < .01); with the EA/FC group scoring in between and not different from either of the other groups. When only the subset with usable ERP data were analyzed, similar results were found. Both the main effect of trial type (F(1, 51) = 10.03, p = .003, η2p = .16), and the main effect of group (F(2, 51) = 6.66, p = .003, η2p = .21) were significant. The interaction effect was not significant, F(2,51) = .19, ns.

The PI group was less accurate than both of the other groups (ps < .01). The EA/FC group did not significantly differ from the NA group. Because CRM performance correlated with IQ, r(75) = .29, p = .012, the full sample analysis was repeated covarying IQ. The group effect remained marginally significant with IQ covaried, F (2, 71) = 2.63, p = .07, η2p = .07.

Reaction time

There was a significant main effect of trial type, F(1, 72) = 15.23, p < .001, η2p = .18, such that children were significantly faster when correctly identifying old items as compared to new. However, there was no significant main effect of group (F(2, 72) = 1.19, ns) and no interaction effect (F(2, 72) = .81, ns). Similar results were obtained (i.e., a significant main effect of trial type) when the ERP subsample was analyzed.

Correlations between CRM and PAL performance

Using the whole sample (n = 75), Pearson correlations revealed a significant negative relation between overall accuracy on the CRM task and total errors on the PAL task (r = −.32, p = .005). This correlation was also significant in the reduced ERP subsample (r = −.28, p = .037).

Electrophysiological Signal Amplitude

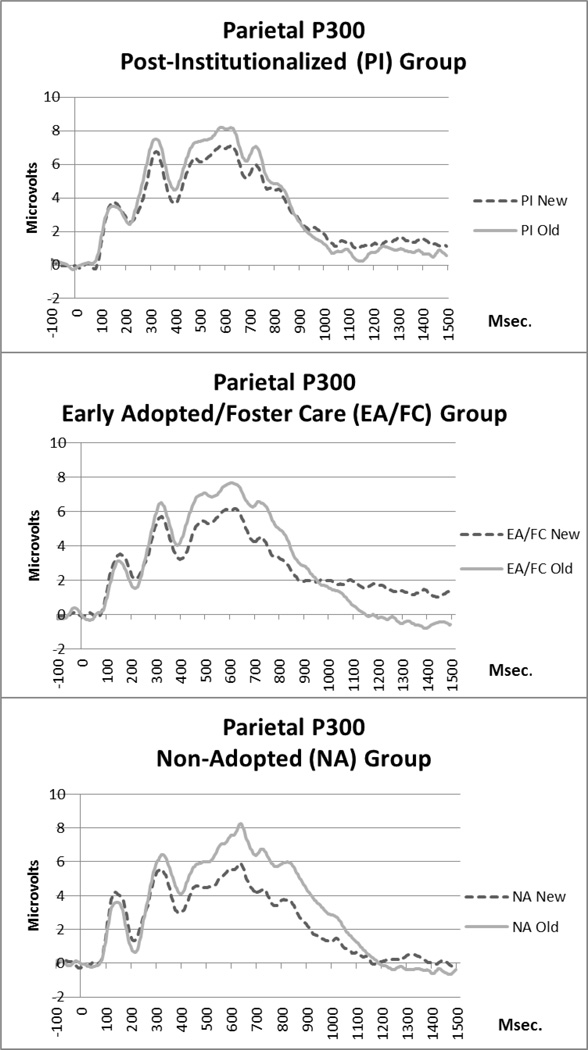

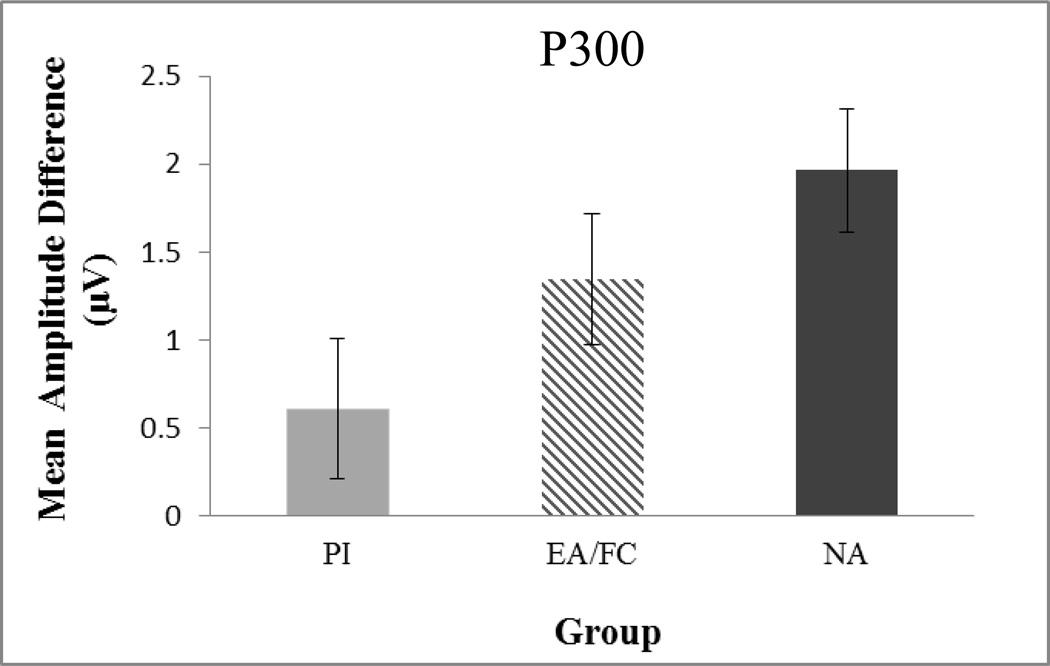

Parietal P300

Average waveforms by trial type and group are presented in Figure 4. There was a main effect of trial type (F(1, 51) = 40.98, p < .001), with higher mean amplitudes during old trials compared to new (Mnew= 4.00 µV, Mold = 5.33 µV, SEs = .37,.35). There was also a significant trial type by group interaction (F(2,51) = 3.56, p = .036) and a significant trial type by hemisphere interaction (F(1,51) = 4.8, p = .033). There were no other significant main or interaction effects.

Figure 4.

Waveforms for parietal P300 component by group.

For the trial type by group interaction, follow-up t-tests revealed that the new amplitude differed from the old amplitude in the NA group (Mnew = 3.54 µV, Mold = 5.55 µV, SEs = .61, .57; t(19) = 2.41, p =.02), but not in the EA/FC group (Mnew = 3.81 µV, Mold = 5.11 µV, SEs = .64, .60; t(17) = 1.49, p=.15) or in the PI group (Mnew = 4.65 µV, Mold = 5.31 µV, SEs = .68, .63; t(15) = .71, p=.48). In order to examine this interaction more carefully, we also calculated a new-old difference score for mean amplitude and conducted a GLM to examine group differences (see Figure 5 for group means). There was a significant effect of group (F(2,51) = 3.25, p = .047), with post hoc tests revealing the NA group had a significantly higher new-old amplitude difference score than the PI group (p = .04). The EA group difference score fell in between and did not differ significantly from either group. Notably, IQ was not correlated with the old-new difference, therefore not used as a covariate in these analyses.

Figure 5.

Estimated marginal means of the difference in new/old mean amplitude for the parietal P300 by group. Error bars represent ±SEM. PI = Post-institutionalized, EA/FC = Early Adopted Foster Care, NA = Non-adopted.

For the trial type by hemisphere interaction, follow-up tests revealed significantly higher amplitudes for old compared to new only in the left hemisphere (Left: Mnew = 4.01 µV, Mold = 5.68 µV; SEs = .40, .42; t(53) = 2.87, p = .005; Right: Mnew = 3.99 µV, MOld = 4.97 µV, SEs = .45, .40; t(53) = 1.63, p=.11).

Frontal N1

The main effect of trial type was significant (F(1,51) = 17.02, p <.001; Mnew = − 7.45 µV; Mold = − 6.66 µV, SEs = .40, .42). There were no other significant main effects or interactions.

Frontal P2

There was a significant main effect of trial type (F(1, 51) = 29.02, p < .001; Mnew = − 8.69 µV, Mold = − 7.66 µV; SEs =.50, .46), with no other significant main effects or interactions.

Frontal N2

There were no significant main effects or interactions for N2 amplitude.

Correlations between ERP Components and Behavioral Measures

Finally, we examined associations between behavioral performance on the CRM task (accuracy for both old and new items) and ERP measures in an attempt to discern the neural correlates of this memory task. Across groups, CRM accuracy was not significantly correlated with mean amplitude for new or old trials for any of the components. When we conducted correlations within each group, the only significant result was in the PI group: frontal N1 mean amplitude for old items was significantly correlated with accuracy for old items (r(14) = −.63, p = .009). That is, in the PI group only, stronger negative deflection in the frontal region for old items was associated with higher accuracy in identifying items as old.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined whether children adopted from institutions as infants and toddlers exhibited memory deficits at 9–11 years of age compared to children who were born and raised in their biological families. Using both behavioral and electrophysiological indices of memory function, we compared children who had spent a large portion of their lifetime in institutional care prior to being adopted at age 12 months or older (PI group) to both children who had spent less than 2 months in institutional care and were adopted from foster care overseas before 8 months of age (EA/FC group), and to children who were born and raised in their birth families (NA group). The children were tested behaviorally on a continuous recognition memory (CRM) task and the Paired Associates Learning task (PAL). In addition, ERPs were collected during the CRM task. Both the CRM task and the PAL task measure episodic memory. Paired Associates Learning is a test of visual episodic memory with additional demands of associative learning (Sahakian & Owen, 1992). Both of the tasks are thought to rely on medial temporal lobe function.

Group differences in accuracy were found for both memory measures. On the PAL task, the PI group made more errors than both the EA/FC and the NA groups. However, on average, performance of the EA/FC group was equivalent to that of the NA group. The finding that EA/FC group did not differ from the NA group suggests that the effect is not due to factors related to adoption per se but to duration of institutionalization and age at adoption. On the CRM task, more PI children were unable to perform the task at a level permitting analysis (e.g., 60% accuracy) compared to the other groups. Even among those reaching the 60% accuracy requirement for analysis, PI children were less accurate than the NA group at identifying items as never-seen (new) or repeated (old). The EA/FC group performed slightly better than the PI group and worse than the NA group but the difference from either group did not reach statistical significance. The three groups did not differ from each other on reaction time during the CRM task. However, the PI group exhibited larger standard deviations in reaction times and on average lower reaction times. This may be indicative of their deployment of a different strategy during this task. The larger variability of performance in the PI sample in many measures may illustrate the effects of deprivation, as a wider range of early experiences and insults often results in more heterogenous groups. Thus, converging behavioral evidence from two different tasks indicates that memory is one type of cognitive function that is vulnerable to early psychosocial deprivation, with effects that persist into middle childhood.

In addition to behavioral performance, ERP indices of recognition memory were also analyzed. Overall, children showed evidence of a parietal episodic memory effect; that is, larger P300 amplitude for correctly recognized (old) items compared to correctly rejected (new) items. This finding is consistent with the previous developmental literature on P300 correlates of recognition memory (Berman et al., 1990; Cycowicz et al., 2003). Group differences in the P300 old/new effect were also observed, such that the effect was reduced in the PI group. Even though the P300 amplitude for new or old items did not differ significantly between the groups, the difference in amplitude between new and old items was significantly smaller for the PI group than for the NA group. This reduced old/new effect is similar to those reported in studies of adults with hippocampal lesions (Johnson, 1995; Rugg et al., 1991; Smith & Halgren, 1989), and may have contributed to the lower recognition memory performance of the PI group compared to the other two groups. It is important to note that behavioral results and ERP results were not directly correlated, and thus are not redundant with each other, and both provide unique insight into alterations in memory processing in the PI group.

It is possible that the PI group relied on different processes compared to other groups to accomplish true recognition. One widely accepted perspective on recognition memory supports the dual-process model which posits that recognition is based on processes of recollection and familiarity (Yonelinas, 2002). According to this model, the two processes are distinct, and thus, it is possible to make correct item recognition judgments through familiarity processes alone. Recently, researchers have begun to discover ERP components that are sensitive to familiarity processes. It has been argued that a frontal wave that peaks 300–500 msec following stimulus onset (FN400) indexes familiarity (Rugg & Curran, 2007, for a review). A similar effect was also shown in 8- to 10-year-old children in a study by Mecklinger, Brunnemann, and Kipp (2010). In the present study, we also observed a frontal negative component (N2) that was similar to FN400. However, this component did not show a new/old memory effect, and thus it is unclear if it can be labeled as a familiarity component. This component might not be reliable in children. For example, Czernochowski et al. (2009) failed to find a midfrontal old/new effect in children. In addition, we did not find any group differences in this N2/FN400 component, and thus have no evidence that children who experienced early deprivation might be differentially relying on familiarity processes compared to non-adopted children.

It is possible that the recognition memory deficits and the reduced old/new effect observed in the PI children are due to difficulties with attention allocation. It has been shown that PI children are more likely to have problems with inattention and impulsivity and to develop symptoms of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Kreppner, O’Connor, & Rutter, 2001; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Pollak et al., 2010). In addition to the parietal P300 ERP component, in the present study we also examined group differences in frontal components that have been shown to be involved in attentional processes. The PI children did not differ from the two comparison groups on the N1, N2 and P2 components, and thus did not show evidence of deficits in basic attention processing on the continuous recognition memory task. However, it is important to point out that the sample of children that completed the ERP data collection process and provided data that survived the preprocessing steps most likely differed on basic attention processes from the sample that did not. Although group differences were not significant on the N1 component, stronger N1 deflection was associated with higher memory performance in the PI group suggesting that attentional mechanisms play an important role in helping PI children achieve success on this memory task.

In the present study, we did not find large differences in neurophysiological indices of recognition memory between post-institutionalized internationally adopted children, children adopted early from foster care and never-adopted children. This finding is inconsistent with the expectations from animal models that show early chronic stress is detrimental to the hippocampus (Sanchez, Ladd, & Plotsky, 2001, for a review) and from studies with human adults that show hippocampal volume reductions after experiencing extremely stressful situations in childhood (e.g., Bremner et al., 1997). However, our findings fit with those recently reported in Tottenham et al. (2010) that PI children do not have smaller hippocampal volume compared to non-adopted and hence never institutionalized children. Tottenham et al. suggested that this null effect might be a result of growing up in an enriched environment following adoption. Other authors also point out that hippocampal volume differences may emerge in adulthood (Andersen et al., 2008), suggesting that further long term studies are needed to delineate the effects of early adversity on hippocampally-mediated memory tasks.

In addition, larger group differences in neural processes of memory function might become evident when the memory demand is increased in the form of requests for contextual details or source memory. For example, there is evidence in the literature that explicit relational memory is supported by the medial temporal lobes and that hippocampal structures show increased activity during relational memory compared to memory for items (Davachi, 2006; Meltzer & Constable, 2005). Thus, future investigation of neural correlates of relational memory or source memory, using ERPs or fMRI, might reveal even larger differences in the organization of brain networks between post-institutionalized and never-adopted children.

There are several limitations to our study. The first is that we had a relatively restricted group of PI children on whom we could conduct the ERP analysis. Those in the ERP analysis represented only 53% of the PI sample, compared to 68% of the NA sample. Given that those children who did not have usable ERP data performed more poorly on the CRM and PAL tasks than did those with usable data, it seems likely that our ERP analysis reflected neural activity among the more competent of PI children. Second, although we used the EA/FC children as a rough control for adversity common to abandoned children placed in institutional and foster care, these two groups differed in more than just their institutional care histories. They came from different countries because, at the time these children were adopted, countries differed in whether foster care or institutions were used to care for orphaned or abandoned children. The EA/FC children were younger at adoption than were the PI children. This difference reflects the modal ages at which children from these different types of care arrangements typically arrive in their adoptive families, but it means that time in the adoptive family and age at arrival also differed for these two groups and might be contributing to differences in memory performance. Third, it is likely that the NA children differed from the EA/FC and PI children not only in postnatal, but also in prenatal conditions that might influence neurobehavioral development. This, of course, makes the general lack of difference between the NA and EA/FC groups all the more striking. Finally, we were examining a convenience sample of both internationally adopted and non-adopted children. Even though the registry for the internationally-adopted children reflects about 60% of the children adopted into the state of Minnesota over the years the children in the present study were adopted, we do know that it was still the case that parents who joined the registry were more highly educated than parents who declined joining (Hellerstedt et al., 2008). Thus it is possible that, were we to have access to a more representative sample, our findings might have varied.

Nonetheless, our results corroborate the findings of Pollak et al. (2010) and Bos et al. (2009) in showing that memory function is one of the domains that is negatively influenced by early deprivation. However, in the present sample, as we did not assess other cognitive functions, we cannot judge whether memory issues are particularly salient for PI children or are only among multiple cognitive deficits associated with early institutional care. The present research adds to the literature by examining the neural processes that underlie successful recognition memory in children who experienced early adversity in the form of living 75 % of their pre-adoption life under sub-standard conditions without adequate stimulation for optimal brain and cognitive growth. This is the first study to use event-related potentials during middle childhood to study higher-level cognition in post-institutionalized and adopted children. Additional research is needed to more closely examine the impact of these poor conditions on brain development by using other noninvasive brain imaging techniques such as functional MRI and diffusion tensor imaging. Future research should also investigate the long-term consequences of early deprivation by following children into adolescence and adulthood.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the R01 MH068857 grant to Megan R. Gunnar, an M01 RR00400 grant to the U of M GCRC and by the Center for Neurobehavioral Development, University of Minnesota. The authors also thank Bonny Donzella, Stephanie Clarke, and Amy Monn for assistance with data collection, Seth D. Pollak for his help with the study design and the children and families that so generously gave their time to make the work possible.

Footnotes

This article is a pre-print version. The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

Portions of these data were presented at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, April 2009.

Given that we had a sampling rate of 400 Hz and we wanted to have at least 10 data points to estimate each matrix weight (64 × 64 weights) for the ICA algorithm, we determined the minimum number of trials each participant would need to have using the following equation: 400 × Trial number = 10 × 642, thus the minimum trial number was 102.4, so we imposed a minimum number of 102 trials.

Lag comparisons were not included in the present analysis to preserve trial numbers for the old versus new comparison.

Contributor Information

O. Evren Güler, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota.

Camelia E. Hostinar, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota

Kristin A. Frenn, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota

Charles A. Nelson, Division of Developmental Medicine, Children’s Hospital Boston and Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School

Megan R. Gunnar, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota

Kathleen M. Thomas, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota

References

- Andersen SL, Tomada A, Vincow ES, Valente E, Polcari A, Teicher MH. Preliminary evidence for sensitive periods in the effect of childhood sexual abuse on regional brain development. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences. 2008;20:292–301. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20.3.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PJ, Wiebe SA, Carver LJ, Lukowski AF, Haight JC, Waters JM, Nelson CA. Electrophysiological indices of encoding and behavioral indices of recall: Examining relations and developmental change late in the first year of life. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2006;29:293–320. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2902_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PJ, Wiebe SA, Carver LJ, Waters JM, Nelson CA. Developments in long-term explicit memory late in the first year of life: Behavioral and electrophysiological indices. Psychological Science. 2003;14:629–635. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett C, Maughan B, Rutter M, Castle J, Colvert E, Groothues C, Kreppner J, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Do the effects of early severe deprivation on cognition persist into early adolescence? Findings from the English and Romanian adoptees study. Child Development. 2006;77:696–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat EM, Williams WJ, Gehring WJ. Decomposing ERP time-frequency energy using PCA. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116(6):1314–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman S, Friedman D. A developmental study of ERPs during recognition memory: Effects of picture familiarity, word frequency, and readability. Journal of Psychophysiology. 1993;7:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Berman S, Friedman D, Cramer M. A developmental study of event-related potentials to pictures and words during explicit and implicit memory. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 1990;10:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(90)90034-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos KJ, Fox N, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA. Effects of early psychosocial deprivation on the development of memory and executive function. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;3:1–7. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.016.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Randall P, Vermetten E, Staib L, Bronen RA, Mazure C, Capelli S, McCarthy G, Innis RB, Charney DS. Magnetic resonance imaging-based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood physical and sexual abuse–a preliminary report. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;41:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00162-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozinsky CJ, Yonelinas AP, Kroll NE, Ranganath C. Lag-sensitive repetition suppression effects in the anterior parahippocampal gyrus. Hippocampus. 2005;15(5):557–61. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Earls F. Psychological and neuroendocrinological sequelae of early social deprivation in institutionalized children in Romania. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;807:419–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver LJ, Bauer PJ, Nelson CA. Associations between infant brain activity and recall memory. Developmental Science. 2000;3:234–246. [Google Scholar]

- Chugani HT, Behen ME, Muzik O, Juhasz C, Nagy F, Chugani DC. Local brain functional activity following early deprivation: A study of postinstitutionalized Romanian orphans. Neuroimage. 2001;14:1290–1301. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvert E, Rutter M, Kreppner J, Beckett C, Castle J, Groothues C, Hawkins A, Stevens S, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Do theory of mind and executive function deficits underlie the adverse outcomes associated with profound early deprivation?: findings from the English and Romanian adoptees study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1057–1068. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cycowicz YM, Friedman D, Duff M. Pictures and their colors: What do children remember? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2003;15(5):759–768. doi: 10.1162/089892903322307465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czernochowski D, Mecklinger A, Johansson M. Age-related changes in the control of episodic retrieval: an ERP study of recognition memory in children and adults. Developmental Science. 2009;12(6):1026–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czernochowski D, Mecklinger A, Johansson M, Brinkmann M. Age-related differences in familiarity and recollection: ERP evidence from a recognition memory study in children and young adults. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;5:417–433. doi: 10.3758/cabn.5.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L. Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2004;134:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrova-Krol NA, van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Cyr C, Juffer F. Physical growth delays and stress dysregulation in stunted and non-stunted Ukrainian institution-reared children. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins IG, Davachi L. Functional neuroimaging of episodic. In: Cabeza R, Kingston A, editors. Handbook of functional neuroimaging of cognition. 2nd edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2006. pp. 229–268. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annual Reviews of Neuroscience. 2007;30:123–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Electrical Geodesics, Inc. Geodesic sensor net: Technical manual. Eugene, OR: Electrical Geodesics, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eluvathingal TJ, Chugani HT, Behen ME, Juhasz C, Muzik O, Maqbool M, Chugani DC, Makki M. Abnormal brain connectivity in children after early severe socioemotional deprivation: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2093–2100. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. Cognitive event-related potential components during continuous recognition memory for pictures. Psychophysiology. 1990;27:136–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghetti S, DeMaster DD, Yonelinas AP, Bunge SA. Developmental differences in medial temporal lobe function during memory encoding. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(28):9548–9556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3500-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Morison SJ, Chisholm K, Schuder M. Salivary cortisol levels in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:611–628. doi: 10.1017/s095457940100311x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstedt WL, Madsen NJ, Gunnar M, Grotevant HD, Lee RM, Johnson DE. The international adoption project: Population-based surveillance of Minnesota parents who adopted children internationally. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008;12:162–171. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson RN. A mini-review of fMRI studies of human medial temporal lobe activity associated with recognition memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2005;58B:340–360. doi: 10.1080/02724990444000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth SL, Rovet JF, Taylor MJ. Neurophysiological correlates of verbal and nonverbal short-term memory in children: Repetition of words and faces. Psychophysiology. 2001;38:594–600. doi: 10.1017/s0048577201002281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillyard SA, Vogel EK, Luck SJ. Sensory gain control (amplification) as a mechanism for selective attention: Electrophysiological and neuroimaging evidence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences. 1998;353:1257–1270. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy AS, Rex CS, Chen Y, Dubé C, Maras PM, Grigoriadis DE, et al. Hippocampal dysfunction and cognitive impairments provoked by chronic early-life stress involve excessive activation of CRH receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:13005–13015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1784-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE. Medical and developmental sequelae of early childhood institutionalization in Eastern European adoptees. In: Nelson CA, editor. The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology. Vol 31: The effects of early adversity on neurobehavioral development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 113–162. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, Muftuler LT, Rugg MD. Multiple repetitions reveal functionally and anatomically distinct patterns of hippocampal activity during continuous recognition memory. Hippocampus. 2008;18:975–980. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. On the neural generators of the P300: Evidence from temporal lobectomy patients. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1995;44:110–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertes DA, Gunnar MR, Madsen NJ, Long J. Early deprivation and home basal cortisol levels: A study of internationally-adopted children. Development & Psychopathology. 2008;20:473–491. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korosi A, Baram TZ. Plasticity of the stress response early in life: Mechanisms and significance. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52:661–670. doi: 10.1002/dev.20490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreppner JM, O’Connor TG, Rutter M the English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. Can inattention/overactivity be an institutional deprivation syndrome? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:513–528. doi: 10.1023/a:1012229209190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman MM, Wiik KL, Frenn KA, Pollak SD, Gunnar MR. Postinstitutionalized children's development: Growth, cognitive, and language outcomes. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30:426–434. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181b1fd08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Hillyard SA. Electrophysiological correlates of feature analysis during visual search. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:291–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean K. The impact on institutionalization on child development. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:853–884. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makeig S, Debener S, Onton J, Delorme A. Mining event-related brain dynamics. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2004;8(5):204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangun GR, Hillyard SA. Electrophysiological studies of visual selective attention in humans. In: Scheibel AB, Wechsler AF, editors. Neurobiology of higher cognitive function. New York: Guilford; 1990. pp. 271–295. [Google Scholar]

- Mangun GR, Hillyard SA, Luck SJ. Electrocortical substrates of visual selective attention. In: Meyer D, Kornblum S, editors. Attention and performance XIV. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1993. pp. 219–243. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall DH, Drummey AB, Fox NA, Newcombe NS. An event-related potential study of item recognition memory in children and adults. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2002;3:201–224. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall PJ, Fox NA the Bucharest Early Intervention Project Core Group. A comparison of the electroencephalogram between institutionalized and community children. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:1327–1338. doi: 10.1162/0898929042304723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87:873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Sheridan MA, Marshall P, Nelson CA. Delayed maturation in brain electrical activity partially explains the association between early environmental deprivation and symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecklinger A, Brunnemann N, Kipp K. Two process for recognition memory in children of early school age: An event-related potential study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;23(2):435–446. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer JA, Constable T. Activation of human hippocampal formation reflects success in both encoding and cued recall of paired associates. Neuroimage. 2005;24:384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Boyett-Anderson JM, Reiss AL. Maturation of medial temporal lobe response and connectivity during memory encoding. Cognitive Brain Research. 2005;25:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulson MC, Westerlund A, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA. The effects of early experience on face recognition: An event-related potential study of institutionalized children in Romania. Child Development. 2009;80:1039–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R, Picton TW. N2 and automatic versus controlled processes. In: McCallum WC, Zappoli R, Denoth F, editors. Cerebral psychophysiology: Studies in event-related potentials. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1986. pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Collins PF, Torres F. P300 brain activity in patients preceding temporal lobectomy. Archives of Neurology. 1991;48:141–148. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530140033014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, McCleery JP. The use of event-related potentials in the study of typical and atypical development. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(11):1252–1261. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318185a6d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Monk CM. The use of event-related potentials in the study of cognitive development. In: Nelson CA, Luciana M, editors. Handbook of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2001. pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Thomas KM, de Haan M, Wewerka SS. Delayed recognition memory in infants and adults as revealed by event-related potentials. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 1998;29(2):145–165. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(98)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D. Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science. 2007;318:1937–1940. doi: 10.1126/science.1143921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofen N, Kao Y-C, Sokol-Hessner P, Kim H, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Gabrieli J. Development of the declarative memory system in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10(9):1198–1205. doi: 10.1038/nn1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SW, Nelson CA the BEIP Core Group. The impact of early institutional rearing on the ability to discriminate facial expressions of emotion: An event-related potential study. Child Development. 2005a;76(1):54–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SW, Nelson CA the BEIP Core Group. An event-related potential study of the impact of institutional rearing on face recognition. Developmental Psychopathology. 2005b;17:621–639. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond J, Nelson CA. Accounting for change in declarative memory: A cognitive neuroscience perspective. Developmental Review. 2007;27:349–373. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Nelson CA, Schlaak MF, Roeber BJ, Wewerka SS, Wiik KL, Frenn KA, Loman MM, Gunnar MR. Neurodevelopmental effects of early deprivation in postinstitutionalized children. Child Development. 2010;81:224–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Curran T. Event-related potentials and recognition memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Nagy ME. Event-related potentials and recognition memory for words. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1989;72:395–406. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(89)90045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Roberts RC, Potter DD, Pickles CD, Nagy ME. Event-related potentials related to recognition memory: Effects of unilateral temporal lobectomy and temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 1991;114:2313–2332. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakian BJ, Owen AM. Computerized assessment in neuropsychiatry using CANTAB: Discussion paper. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1992;85:399–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MM, Ladd CO, Plotsky PM. Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: Evidence from rodent and primate models. Developmental Psychopathology. 2001;13:419–449. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloerscheidt AM, Rugg MD. Recognition memory for words and pictures: an event-related potential study. NeuroReport. 1997;8:3281–3285. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199710200-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ME, Halgren E. Dissociation of recognition memory components following temporal lobe lesions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1989;15:50–60. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.15.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, Garvin MC, Gunnar MR. Atypical EEG power correlates with indiscriminately friendly behavior in internationally adopted children. Developmental Psychology. 2010 doi: 10.1037/a0021363. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DG, Grice JW, Najm-Briscoe RG, Miller JW. The influence of unequal numbers of trials on comparisons of average event-related potentials. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2004;26(3):753–774. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2603_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Hare TA, Quinn BT, McCarry K, Nurse M, Gilhooly T, Casey BJ. Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically larger amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation. Developmental Science. 2010;13:46–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Poelhuis CWK. Adoption and cognitive development: A meta-analytic comparison of adopted and nonadopted children’s IQ and school performance. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;113(2):301–316. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Luijk MPCM, Juffer F. IQ of children growing up in children’s homes: A meta-analysis on IQ delays in orphanages. Merill-Palmer Quarterly. 2008;54(3):341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien JW, Glimmerveen JC, Franken IHA, Martens VEG, de Bruin EA. Age-related differences in brain electrical activity during extended continuous face recognition in younger children, older children and adults. Developmental Science. 2011;14(5):1107–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwert RE, Marshall PJ, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA. Timing of intervention affects brain electrical activity in children exposed to severe psychosocial neglect. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola FC, Thorne J, Edmonds B, Schneider T, Eichele T, Debener S. Semi-automatic identification of independent components representing EEG artifact. C. linical Neurophysiology. 2009;120(5):868–877. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC–III) 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wegesin DJ, Nelson CA. Effect of inter-item lag on recognition memory in seizure patients preceding temporal lobe resection: Evidence from event-related potentials. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2000;37:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilding E, Rugg M. An event-related potential study of recognition memory with and without retrieval of source. Brain. 1996;119:889–905. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.3.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wismer Fries AB, Shirtcliff EA, Pollak SD. Neuroendocrine dysregulation following early social deprivation in children. Developmental Psychobiology. 2008;50:588–599. doi: 10.1002/dev.20319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP. The nature of recollection and familiarity: A review of 30 years of research. Journal of Memory and Language. 2002;46:441–517. [Google Scholar]