Abstract

Objective

Natriuretic peptide signaling is important in the regulation of blood pressure as well as in the growth of multiple cell types. To examine the role of natriuretic peptide signaling in atherosclerosis, we crossbred mice that lack natriuretic peptide receptor A (NPRA; Npr1−/−) with atherosclerosis-prone mice that lack apolipoprotein E (apoE; Apoe−/−).

Methods and Results

Doubly deficient Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice have increased blood pressure relative to Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (118±4 mm Hg compared with 108±2 mm Hg, P<0.05) that is coincident with a 64% greater atherosclerotic lesion size (P<0.005) and more advanced plaque morphology. Additionally, aortic medial thickness is increased by 52% in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice relative to Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (P<0.0001). Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice also have significantly greater cardiac mass (9.0±0.3 mg/g body weight) than either Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (5.8±0.2 mg/g) or Npr1−/− Apoe+/+ mice (7.1±0.2 mg/g), suggesting that the lack of both NPRA and apoE synergistically enhances cardiac hypertrophy.

Conclusions

These data provide evidence that NPR1 is an atherosclerosis susceptibility locus and represents a potential link between atherosclerosis and cardiac hypertrophy. Our results also suggest roles for Npr1 as well as Apoe in regulation of hypertrophic cell growth.

Keywords: natriuretic peptide receptor A, atherosclerosis, cardiac hypertrophy, vascular smooth muscle cells

The natriuretic peptide system plays a critical role in regulating blood volume and blood pressure (BP).1,2 Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide are released mainly from the heart after wall stretch and act through natriuretic peptide receptor A (NPRA) in the kidneys and vasculature to induce natriuresis, diuresis, and vasorelaxation.1,3,4 The importance of the natriuretic system in the etiology of hypertension is demonstrated in mice lacking NPRA (Npr1−/− mice), which have higher than normal BPs.5–7 Considerable evidence suggests that elevated BP might have a direct role in enhancing atherosclerotic lesion formation.8,9

In addition to the endocrine function in BP control, natriuretic peptides released from the heart also act in an autocrine/paracrine loop to inhibit hypertrophic growth of cardiac myocytes.10–12 In Npr1−/− mice, NPR signaling is absent, leading to a marked enhancement of cardiac hypertrophy that is independent of BP.11,13,14 Expression of ANP and B-type NP has also been detected in the vasculature,15 and in vitro evidence suggests that extracardiac autocrine/paracrine NP signaling might negatively regulate hypertrophic growth of both endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs).16,17 Thus, through both endocrine and local functions, NPs likely play a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, and the NPR1 locus is therefore a potential candidate as a genetic risk factor for atherosclerosis.

Proving a direct causal role of mutations in a candidate gene in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis is complicated by the homeostatic mechanisms that control BP, which might also play a role in atheroma formation. Mouse genetics is a powerful approach to elucidate the cause-effect relation behind hypertension and atherosclerosis and the interaction between these 2 pathological processes. Previously, we have shown that a lack of endothelial nitric oxide synthase results in increased BP and atherosclerotic plaque size in mice deficient for apolipoprotein E (apoE; Apoe−/− mice) that spontaneously develop atherosclerosis.18,19 Here we have used a similar genetic approach to test the effects on atherosclerosis of a deficiency in NPRA. We demonstrate that mice lacking both NPRA and apoE (Npr1−/− Apoe−/−) have increased atherosclerosis compared with apoE-deficient mice that are of the wild-type for Npr1 (Npr1+/+ Apoe−/−). These mice also have increased BP as well as markedly greater aortic wall thickness relative to Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice, indicating a role for NP signaling in the development of atherosclerosis.

Methods

Mice

All mouse experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Carolina. Mice were fed a normal chow diet. The Npr1−/− mice that were sixth generation–backcrossed to C57BL/6 were bred with Apoe−/− mice that were also backcrossed at least 8 times to C57BL/6. Npr1+/− Apoe+/− mice were then crossed with Apoe−/− mice to generate Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice. To minimize contributions to the phenotypes of the strain differences remaining in the experimental animals, most of the Npr1+/+ Apoe−/−, Npr1+/− Apoe−/−, and Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice used for the experiments were littermates of an intercross between Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice. An intercross between Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice and Npr1+/− Apoe+/+ yielded those of the Apoe+/− background used in the current experiments. Npr1 genotype was determined by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primer I (5′-GCA TGG TTC AGC TCT AAG AC-3′), primer II (5′-CTA ACC CTG TGA ACT GTA AGC-3′), and primer III (5′-CCT TCA GTT ATC TAC ATC TGC-3′) at a concentration ratio of 2:1:4. PCR with primers I and II amplifies a 550-bp fragment corresponding to the inactivated Npr1 gene, whereas PCR with primers I and III amplifies a 350-bp fragment indicative of the wild-type Npr1 gene. Apoe genotype was determined by multiplex PCR with primer I (5′-AGA ACT GAC GTG AGT GTC CA-3′), primer II (5′-GTT CCC AGA AGT TGA GAA GC-3′), and primer III (5′-CTT CCT CGT GCT TTA CGG TA-3′) at a concentration ratio of 1:2:1. A 300-bp product indicated the wild-type Apoe gene, and a 220-bp product indicated the inactivated locus.

Plasma Analyses

Plasma ANP level was measured by radioimmunoassay as previously described,8 and total cholesterol and triglycerides were measured by colorimetric assay (Sigma). HDL cholesterol was measured after removing apoB-containing lipoproteins by precipitation with polyethylene glycol. Plasma creatinine was measured by using a VT250 chemical analyzer (Johnson & Johnson).

BP Analysis

BPs were measured by the noninvasive tail-cuff method20 on conscious, restrained mice 3 to 4 months of age. The BP of each mouse was the average of the daily means of 6 consecutive days measured with two machines, each with 4 channels (Visitech). Each mouse was subjected to a total of 40 inflations (4 trials of 10 inflations) per day on a different channel each day. The first trial of 10 inflations allowed the mouse to warm up and acclimate to the cuff; these data were discarded. Data from the next 3 trials, each of 10 inflations, were recorded. Daily means were calculated from the means of the 3 trials per day.

Atherosclerotic Lesion Analysis

Animals were euthanized with an overdose of 2,2,2-tribromoethanol at 4 months of age, and the vascular tree was perfused either with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline or with phosphate-buffered saline under physiological pressure. Segments of the aortic sinus were embedded, sectioned, and stained as described previously.21 Plaque size was measured with NIH IMAGE, version 1.59, and the average of the 4 sections chosen by strict anatomic criteria was taken as the mean lesion size for each animal. To evaluate plaque formation in other parts of the aorta, the aortic tree was dissected free of surrounding tissue and examined under a dissection microscope.

Media Thickness of Aorta and Cardiac Mass Measurements

Cross sections of aorta immediately superior to the aortic sinus and containing no atherosclerotic plaques were used to measure the thickness of the tunica media of the ascending aorta of each animal. Medial area was determined by tracing the area between the internal elastic lamina and external elastic lamina of the vessel with NIH image, version 1.59, to represent the average wall thickness. For cardiac mass measurements, hearts were excised after whole-body perfusion, blotted dry, and weighed.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SE. ANOVA with JMP statistical software (SAS Institute) was used for the main data analysis, and probability values are from the F test unless otherwise stated. Means of Npr1−/− and Npr1+/+ mice and means between Npr1+/− and Npr1+/+ mice were compared with Tukey's honestly significant difference test. Lesion size was analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with sex and genotype as the 2 factors. BP, medial thickness of aorta, and heart weight per body weight (HW/BW) did not differ by sex, and thus, data from males and females were analyzed together. Effect of sex and BP on the lesion sizes in Npr1+/− Apoe+/− and Npr1+/− Apoe+/− mice was estimated by linear regression models.

Results

Npr1−/− Mice Have Decreased Survival During the Neonatal Period

Doubly homozygous Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice were born at the expected frequency from Npr1+/− Apoe−/− × Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mating, as judged by the genotypes of day 1 pups (24 Npr1−/− Apoe−/−, 62 Npr1+/− Apoe−/−, and 34 Npr1+/+ Apoe−/−; P>0.39 by χ2 analysis after assuming a 1:2:1 ratio). However, at weaning (21 days of age), the number of Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice was significantly reduced compared with Npr1+/− Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (12:106:59, P<0.0001 by χ2 analysis). This early death phenomenon is due to Npr1 deficiency rather than Apoe deficiency or a combination thereof, because Npr1−/− Apoe+/+ mice also had decreased survival by day 21 compared with Npr1+/− Apoe+/+ and Npr1+/+ Apoe+/+ mice (4:33:20, P<0.01 by χ2 analysis) on the C57BL/6 background. Both Npr1−/− Apoe−/− and Npr1−/− Apoe+/+ mice that survived beyond 21 days of age appeared to have longevity similar to that of Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe+/+ mice. Thus, the Npr1 genotype–dependent death was limited to a window soon after birth, but its cause was not evident in either gross or histologic examination of 1- to 3-day-old pups (not shown).

Npr1−/−Apoe−/− Mice Have Increased BP Compared With Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− Mice

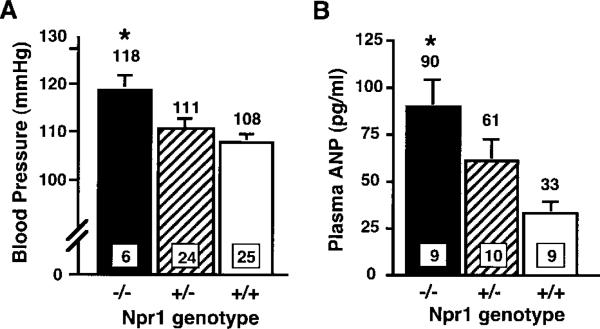

Lack of NPRA causes increased BP in mice, and Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had elevated mean BPs relative to Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (Figure 1A). There is an Npr1 gene-dosage effect (P<0.01) on BP in mice, because Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice had an intermediate BP, but the difference between Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− and Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice did not reach significance.

Figure 1.

Npr1 genotype effect on BP (A) and plasma ANP levels (B). All animals were on the Apoe−/− background. Values in squares at the bottom of bars indicate number of animals, and values above bars are mean values. P<0.02 and P<0.006 by ANOVA for the effect of genotype on BP and on plasma ANP levels, respectively. Error bars represent SE. *P<0.02 vs Npr1+/+ by Tukey's honestly significant difference test.

There was also an Npr1 gene-dosage effect on plasma ANP levels, because Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had significantly higher plasma ANP levels compared with Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (P<0.002; Figure 1B).

Atherosclerotic Plaques in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− Mice Are Increased in Size and Complexity

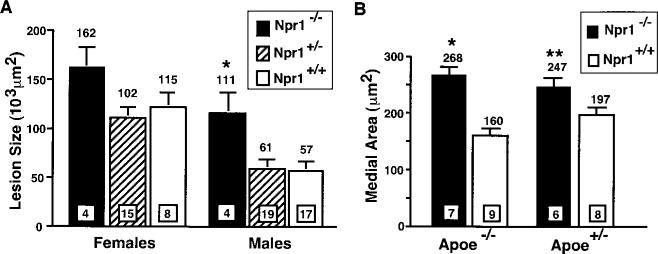

Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had larger average lesion sizes within the proximal aorta compared with Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (Figure 2A). Consistent with previous observations, female Apoe−/− mice had larger average lesion sizes than did males for all Npr1 genotypes. When sex was taken into consideration, the Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had, on average, 64% larger plaques than did Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice, and the effect of Npr1 genotype was significant (P<0.001 by 2-way ANOVA).

Figure 2.

A, Atherosclerotic plaque size within the aortic sinus. All mice were on the Apoe−/− background. Values in squares at the bottom of bars indicate number of animals, and values above the bars are mean area. Error bars represent SE. P<0.001 for Npr1 effect, and P<0.0001 for sex effect by ANOVA. *P<0.005 vs Npr1+/+ males by Tukey's . (B), Areas of the tunica media of the ascending aorta of Npr1−/− and Npr1+/+ mice. P<0.0001 for Npr1 effects on both Apoe−/− and Apoe+/− backgrounds by ANOVA. There is no significant Apoe geno-type effect. *, P<0.0005 and **, P<0.03 versus Npr1+/+ by Tukey's honestly significant difference test.

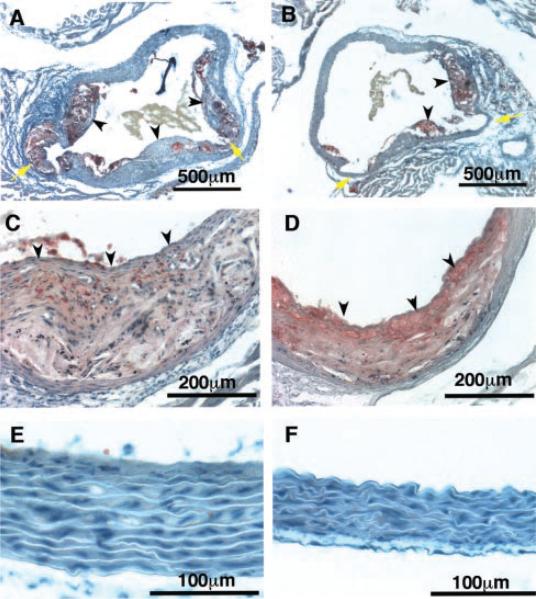

In addition to increased lesion size, plaques in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice were more complex than those in Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice, with, on average notably, larger and more developed fibrous caps and a greater frequency of cholesterol clefts and calcifications (A and C in Figure 3). In contrast, typical lesions present in Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice had less developed fibrous caps and contained acellular and lipid-rich cores (B and D). The coronary ostia of Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice also contained large lesions. Additionally, lesions are more prominent within the right carotid artery and within the aortic arch of Npr1−/− Apoe−/− compared with Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice, in which lesions were limited mainly to the aortic sinus (data not shown). These observations indicate an acceleration of the early stages of plaque development in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice.

Figure 3.

Representative light photomicrographs of proximal aortas of Npr1−/− (A, C, E) and Npr1+/+ (B, D, F) mice on an Apoe−/− background. Sections are stained with Sudan IV and counterstained with hematoxylin. A and B, Coronary ostia (yellow arrows) of female mice. C and D, Aortic roots of male mice. Black arrowheads point to well-developed fibrous caps in Npr1−/− mice compared with thin caps in Npr1+/+ mice. E and F, Medial layers from ascending aortas of male mice.

This increase in lesion size, complexity, and distribution occurred in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice despite the lower plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels relative to Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (Table 1). In parallel with the reduction in total cholesterol, the levels of HDL cholesterol were also significantly lower in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice than in Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice. The plasma lipoprotein distribution analysis by fast liquid column chromatography showed an equal reduction in all classes of lipoprotein fractions (not shown). This difference in plasma lipid levels was not due to changes in blood volume, because hematocrit values were very similar between Npr1−/− Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (Table 1).

Characteristic Measurements of Npr1+/+, Npr1+/– and Npr1–/– Mice on Apoe–/– Background

| Genotype/Sex | Body Weight, g | Cholesterol, mg/dL | Triglyceride, mg/dL | HDL-C, mg/dL | Kidney/Body, mg/g | Hematocrit, % | Creatinine, μmol/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Npr1+/+ Apoe–/– | |||||||

| Males | 28±0.6 (30) | 471±26 (9) | 93±15 (9) | 37±2 (4) | 7.3±0.2 (25) | 43±2 (6) | 38±3 (10) |

| Females | 22±0.5 (18) | 401±38 (7) | 47±4 (7) | 35±3 (4) | 7.0±0.2 (16) | ||

| Npr1+/– Apoe–/– | |||||||

| Males | 27±0.8 (25) | 371±49 (10) | 75±13 (10) | 28±4 (4) | 7.9±0.3 (17) | 43±1 (4) | 35±3 (10) |

| Females | 23±0.6 (16) | 410±16 (7) | 51±3 (7) | 26±3 (6) | 7.4±3.2 (20) | ||

| Npr1–/– Apoe–/– | |||||||

| Males | 31±0.6 (4) | 341±35 (5) | 59±9 (5) | 18±2 (5) | 8.2±0.4 (5) | 44±2 (4) | 31±4 (4) |

| Females | 23±0.3 (4) | 331±47 (5) | 46±6 (5) | 22±5 (4) | 8.3±0.5 (6) | ||

| Genotype effect | P=0.03 | P=0.08 | P<0.001 | P<0.005 | NS | NS | |

| Sex effect | P=0.07 | P<0.001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Data are mean±SE. Animals were between 4 and 9 months old. The numbers of animals are in parentheses. Effects of genotype and sex were analyzed by using two-way ANOVA. NS indicates not significant.

Npr1−/− Apoe−/− Mice Have Increased Medial Thickness of the Aorta

Examination of the aorta proximal to the aortic sinus revealed that Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had thicker aortic walls than did Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice. The increase in wall thickness of the tunica media was pervasive and largely uniform throughout all 360° of the sectioned aorta and was due to marked hypertrophy of VSMCs (Figure 3, E and F).

The aortic sections free of noticeable atherosclerotic plaques were used for morphometric analysis. Ascending aortas of Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had larger medial areas than did those of Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (P<0.0001, Figure 2B). There appeared to be a threshold rather than a gene-dosage effect of the Npr1 genotype, because Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice had a mean area of 164±13×103 μm2 (n=9), similar to that for Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice. The observed increase in medial area was not due to differences in lumen size, because lumen sizes were nearly equal for Npr1−/− Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (681±62×103 μm2 vs 599±55×103 μm2, respectively [not significant]). Moreover, medial area was also increased in Npr1−/− mice on an Apoe+/− background, which did not develop atherosclerotic lesions (P<0.01, Figure 2B).

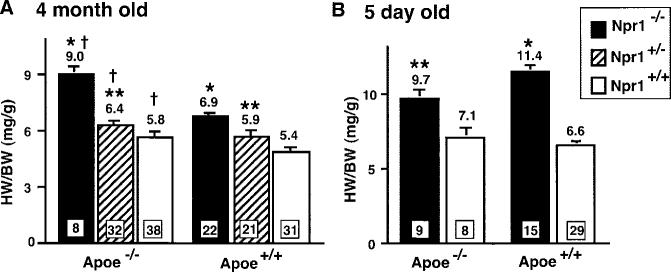

Both Npr1−/− and Apoe−/− Contribute to Cardiac Hypertrophy in Adult Mice

Consistent with our earlier observation that Npr1−/− mice had significant cardiac hypertrophy,11 Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had increased cardiac mass compared with Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice, as determined by their HW/BW at 4 months of age (P<0.0001, Figure 4A). There was also an Npr1 gene-dosage effect, because cardiac mass in Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice was significantly different from that in both Npr1−/− Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (P<0.0001). The gene-dosage effect of Npr1 was also present in mice that were wild-type for Apoe, because both Npr1−/− ApoE+/+ and Npr1+/− Apoe+/+ mice had significantly larger cardiac mass than did Npr1+/+ Apoe+/+ mice (P<0.0001). These data together show a significant effect of Npr1 genotype on HW/BW that was evident in mice on both Apoe−/− and Apoe+/+ backgrounds (P<0.0001, 2-way ANOVA).

Figure 4.

HW/BW in 4-month-old (A) and 5-day-old (B) Npr1 mutants on Apoe−/− and Apoe+/+ backgrounds. Values in squares at the bottom of bars indicate number of animals, and mean values are listed above the bars. Error bars represent SE. P<0.0001 by ANOVA for Npr1 genotypic effect in both adults and pups. Apoe genotype effect is P<0.0001 by ANOVA in adults but not significant in pups. *P<0.005 and **P<0.05 vs Npr+/+; P<0.0005 vs Apoe+/+ by Tukey's honestly significant difference test.

In addition to the Npr1 genotype effect on cardiac mass, there was also a significant Apoe genotype effect (P<0.0001, 2-way ANOVA), because Apoe−/− mice had greater HW/BW than did Apoe+/+ mice for all Npr1 genotypes at 4 months of age (Figure 4A). For instance, Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice had moderately but significantly greater cardiac mass than did Npr1+/+ Apoe+/+ mice (P<0.01), and Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice had an ≈9% greater cardiac mass than did Npr1+/− Apoe+/+ mice (P=0.10). The Apoe effect was most dramatic in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice, which had 27% greater cardiac mass than did Npr1−/− Apoe+/+ mice (P<0.0001), suggesting a synergistic effect of Npr1 and Apoe in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy. Under light microscopy, Npr1−/− Apoe−/− hearts revealed enlargement of individual cardiac myocytes relative to Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe+/+ hearts (data not shown), implicating classically defined cardiac hypertrophy in the synergistic increase in cardiac mass found in doubly deficient mice. Interestingly, whereas the Npr1−/− mice had increased cardiac mass at birth,11 the effect of apoE deficiency on HW was not present in newborn pups. Five-dayold Npr1−/− Apoe−/− pups had higher HW/BW than did Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (P<0.05), but there was no Apoe genotypic effect at this early age, because, for instance, Npr1−/− Apoe−/− pups did not have greater HW/BW than did Npr1−/− Apoe+/+ pups (Figure 4B).

Finally, Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had a significantly higher kidney weight/BW (P<0.005) than did Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice, but there was no difference in plasma creatinine levels, indicating that their renal function was normal (Table 1).

Discussion

Our genetic approach revealed that the lack of Npr1 increases BP, atherosclerotic lesion size, and aortic medial area in Apoe−/− mice. Given that atherosclerosis is increased in mice with hypertension from other causes,18,22–25 increased BP likely contributes to atherogenesis in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice. However, because NPRA has intrinsic growth-inhibitory and antimigratory properties in vitro in endothelial cells and VSMCs,26,27 enhanced atherosclerosis in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice could be due to the loss of local NP signaling. Casco et al15 have reported increased expression of all 3 NPs and their receptors, except for NPRA in human coronary arteries with atherosclerosis. These observations support a possibility that an enhanced NP system is actively modulating the progression of atherosclerosis. We found that circulating ANP levels were higher in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice than in Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (Figure 1B) and therefore, that NP signaling through receptors other than NPRA might be enhanced in the Npr1−/− Apoe−/− aorta. Despite this possible enhancement, however, atherosclerosis was increased in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice. Because of a high incidence of postnatal death of Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice, we were unable to investigate the relative contributions of the physical BP effects and the direct effects of lack of NPRA in the aorta to the enhanced atherosclerosis in these mice. Mice with SMC-selective deletion of Npr1, such as those recently reported,28 could help dissociate the direct and indirect effects on atherosclerosis of the lack of NPRA.

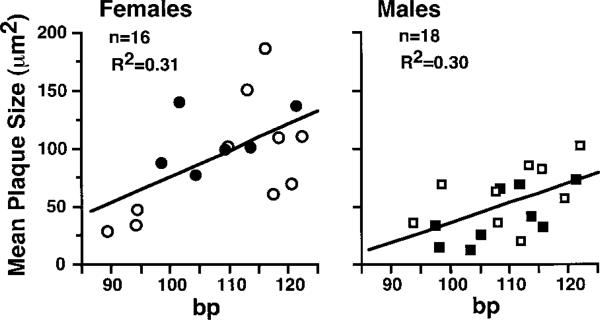

We were also interested in the effects of heterozygous loss of the Npr1 gene, because a quantitative reduction in NPRA function is more likely than is a total loss of function in the human population. We found that neither BP nor plaque size differed significantly between Npr1+/− Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice. Nevertheless, analysis of the 34 mice (16 females and 18 males) in which BP was also measured indicates that the BP of individual animals and their sex together contributed approximately equally to 48% of the overall variance in lesion size (P<0.0001 for sex effect, P<0.0005 for BP effect). The regression analysis in Figure 5 shows that BP explains ≈30% of the variance in lesion size within females as well as within males. A substantial proportion of the variance remains unaccounted for. Plasma cholesterol levels and heart rates did not contribute significantly to the lesion size variance among these mice. Other potential factors include birth weight, litter size, and seasonal changes, but these were not tested.

Figure 5.

Correlation between BP and relative lesion size in individual Npr1+/– Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice. Squares represent males and circles represent females. Open symbols are Npr1+/− Apoe−/− mice, and closed symbols are Npr1+/+Apoe−/− mice.

Intima-media thickening of the aorta and other large vessels is associated with hypertension in humans and is an indicator of future cardiovascular events, including those linked to atherosclerosis.29,30 It is unlikely, however, that the increased wall thickness seen in Npr1−/− mice is due solely to increased BP, and indeed, there were no significant contributions of BP to the wall thickness variance in individual animals among the Npr1+/− Apoe−/− and Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice (n=17). In humans, a BP elevation of 25 mm Hg above normal is associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness of only 6% to 19%.31,32 By contrast, our Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice had a roughly 59% greater medial thickness than did Npr1+/+ Apoe−/− mice with a 10–mm Hg difference in BP. As suggested in vitro26,27 but not confirmed in vivo, lack of antihypertrophic autocrine/paracrine signaling in aortic SMCs likely contributes to the observed increase in medial area of Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice. The extracardiac role for antihypertrophic NPRA signaling highlights the importance of this molecule in the growth control of VSMCs. Previous data have shown that NP signaling can negatively regulate the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes in vitro,10 and the lack of NPRA increases cardiac hypertrophy.5,7,13 Our study confirms these effects of Npr1 on cardiac hypertrophy on both wild-type and Apoe−/− backgrounds. Recent human studies have found an association between left ventricular hypertrophy and intima-media thickness of the carotid and femoral arteries that is independent of BP.33,34 Our data indicate that the Npr1 gene, though likely not alone in this category, could represent a link between these 2 associated conditions in humans. In fact, a BP-independent link between atherosclerosis and cardiac hypertrophy has been proposed to involve the progrowth activity of angiotensin II,35 against which natriuretic signaling could act in both VSMCs and cardiomyocytes.

In addition to the effects of NPRA on cardiac hypertrophy, our results also indicate a potential role of apoE in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Although Apoe−/− mice are more susceptible than wild-type mice to cardiac hypertrophy induced by chronic constriction of the aorta28 and relatively small increases of their cardiac mass with age have been observed,36,37 the current study is the first to demonstrate a direct Apoe−/− genotype effect on cardiac hypertrophy that is synergistic with the effect of NPRA. Given the importance of apoE in lipid transport, apoE might exert its effects directly on the heart, facilitating fatty acid uptake and oxidation, the primary means of energy production in the postfetal heart.38 Supporting this possibility, cardiac hypertrophy in Apoe−/− mice is not observed by 5 days of age (at or just before the energy production shift) but manifests only after the heart increases its demand for fatty acids. Alternatively, the observed Apoe genotype effect on cardiac mass might be not due to Apoe itself but to 129/Ola-derived genes that are closely linked to Apoe and differ functionally from their C57BL/6 counterparts. Genes for dystrophia myotonica–protein kinase, calmodulin 3, and cardiac troponin I are among the potential candidates. In either case, the observed synergistic effect on cardiac hypertrophy in Npr1−/− Apoe−/− mice is likely due to growth stimuli that cannot be curtailed by NP signaling. Further work is required to determine the mechanisms behind the Apoe genotype effects on cardiac hypertrophy suggested by our genetic models.

In conclusion, our results from mice deficient in apoE and NPRA indicate that quantitative changes in functional Npr1 gene expression in humans could enhance atherosclerosis as well as cardiac hypertrophy. They also suggest that genetic alterations in the Apoe gene could enhance not only atherogenesis but also cardiac hypertrophy through as-yet-undetermined mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL42630 and HL62845. The authors thank Drs Leighton James and Nobuyuki Takahashi for useful discussions and reviewing our manuscript and Dr Heejung Bang for advice in statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. Natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:321–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silberbach M, Roberts CT., Jr Natriuretic peptide signalling: molecular and cellular pathways to growth regulation. Cell Signal. 2001;13:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espiner EA. Physiology of natriuretic peptides. J Intern Med. 1994;235:527–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maack T. Role of atrial natriuretic factor in volume control. Kidney Int. 1996;49:1732–1737. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver PM, Fox JE, Kim R, Rockman HA, Kim H-S, Reddick RL, Pandey KN, Milgram SL, Smithies O, Maeda N. Hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and sudden death in mice lacking natriuretic peptide receptor A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14730–14735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez MJ, Wong SK, Kishimoto I, Dubois S, Mach V, Friesen J, Garbers DL, Beuve A. Salt-resistant hypertension in mice lacking the guanylyl cyclase-A receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide. Nature. 1995;378:65–68. doi: 10.1038/378065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliver PM, John SW, Purdy KE, Kim R, Maeda N, Goy MF, Smithies O. Natriuretic peptide receptor 1 expression influences blood pressures of mice in a dose-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2547–2551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chobanian AV, Alexander RW. Exacerbation of atherosclerosis by hypertension: potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1952–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braunwald E. Shattuck Lecture: cardiovascular medicine at the turn of the millennium: triumphs, concerns, and opportunities. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1360–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711063371906. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horio T, Nishikimi T, Yoshihara F, Matsuo H, Takishita S, Kangawa K. Inhibitory regulation of hypertrophy by endogenous atrial natriuretic peptide in cultured cardiac myocytes. Hypertension. 2000;35:19–24. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klinger JR, Warburton RR, Pietras L, Oliver P, Fox J, Smithies O, Hill NS. Targeted disruption of the gene for natriuretic peptide receptor-A worsens hypoxia-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H58–H65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kishimoto I, Rossi K, Garbers DL. A genetic model provides evidence that the receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide (guanylyl cyclase-A) inhibits cardiac ventricular myocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2703–2706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051625598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowles JW, Esposito G, Mao L, Hagaman JR, Fox JE, Smithies O, Rockman HA, Maeda N. Pressure-independent enhancement of cardiac hypertrophy in natriuretic peptide receptor A-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:975–984. doi: 10.1172/JCI11273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn M, Holtwick R, Baba HA, Perriard JC, Schmitz W, Ehler E. Progressive cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in atrial natriuretic peptide receptor (GC-A) deficient mice. Heart. 2002;87:368–374. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casco VH, Veinot JP, Kuroski de Bold ML, Masters RG, Stevenson MM, de Bold AJ. Natriuretic peptide system gene expression in human coronary arteries. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:799–809. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchinson HG, Trindade PT, Cunanan DB, Wu CF, Pratt RE. Mechanisms of natriuretic-peptide-induced growth inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:158–167. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar R, Cartledge WA, Lincoln TM, Pandey KN. Expression of guanylyl cyclase-A/atrial natriuretic peptide receptor blocks the activation of protein kinase C in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of cGMP and cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Hypertension. 1997;29:414–421. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.1.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowles JW, Reddick RL, Jennette JC, Shesely EG, Smithies O, Maeda N. Enhanced atherosclerosis and kidney dysfunction in eNOS(-/-) Apoe(-/-) mice are ameliorated by enalapril treatment. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:451–458. doi: 10.1172/JCI8376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang SH, Reddick RL, Piedrahita JA, Maeda N. Spontaneous hypercholesterolemia and arterial lesions in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Science. 1992;258:468–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1411543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Hagaman JR, Smithies O. A noninvasive computerized tail-cuff system for measuring blood pressure in mice. Hypertension. 1995;25:1111–1115. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang SH, Reddick RL, Burkey B, Maeda N. Diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice heterozygous and homozygous for apolipoprotein E gene disruption. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:937–945. doi: 10.1172/JCI117460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss D, Kools JJ, Taylor WR. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension accelerates the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. Circulation. 2001;103:448–454. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II promotes athero-sclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1605–1612. doi: 10.1172/JCI7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiyama F, Haraoka S, Watanabe T, Shiota N, Taniguchi K, Ueno Y, Tanimoto K, Murakami K, Fukamizu A, Yagami K. Acceleration of athero-sclerotic lesions in transgenic mice with hypertension by the activated reninangiotensin system. Lab Invest. 1997;76:835–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J-H, Hagaman J, Kim S, Reddick RL, Maeda N. Aortic constriction exacerbates atherosclerosis and induces cardiac dysfunction in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:469–475. doi: 10.1161/hq0302.105287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itoh H, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Atrial natriuretic polypeptide inhibits hypertrophy of vascular smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1690–1697. doi: 10.1172/JCI114893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda M, Kohno M, Yasunari K, Yokokawa K, Horio T, Ueda M, Morisaki N, Yoshikawa J. Natriuretic peptide family as a novel antimigration factor of vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:731–736. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.4.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holtwick R, Gotthardt M, Skryabin B, Steinmetz M, Potthast R, Zetsche B, Hammer RE, Herz J, Kuhn M. Smooth muscle-selective deletion of guanylyl cyclase-A prevents the acute but not chronic effects of ANP on blood pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7142–7147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102650499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weidinger F, Frick M, Alber HF, Ulmer H, Schwarzacher SP, Pachinger O. Association of wall thickness of the brachial artery measured with high-resolution ultrasound with risk factors and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1025–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson SK., Jr Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults> Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su TC, Jeng JS, Chien KL, Sung FC, Hsu HC, Lee YT. Hypertension status is the major determinant of carotid atherosclerosis: a community-based study in Taiwan. Stroke. 2001;32:2265–2271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun P, Dwyer KM, Merz CN, Sun W, Johnson CA, Shircore AM, Dwyer JH. Blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and intima-media thickness: a test of the ‘response to injury’ hypothesis of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2005–2010. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.8.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kronmal RA, Smith VE, O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Gardin JM, Manolio TA. Carotid artery measures are strongly associated with left ventricular mass in older adults (a report from the Cardiovascular Health Study). Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:628–633. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaudo G, Schillaci G, Evangelista F, Pasqualini L, Verdecchia P, Mannarino E. Arterial wall thickening at different sites and its association with left ventricular hypertrophy in newly diagnosed essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13:324–331. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pratt RE. Angiotensin II and the control of cardiovascular structure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(suppl 11):S120–S128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartley CJ, Reddy AK, Madala S, Martin-McNulty B, Vergona R, Sullivan ME, Halks-Miller M, Taffet GE, Michael LH, Entman ML, et al. Hemodynamic changes in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2326–H2334. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang R, Powell-Braxton L, Ogaoawara AK, Dybdal N, Bunting S, Ohneda O, Jin H. Hypertension and endothelial dysfunction in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2762–2768. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.11.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barger PM, Kelly DP. Fatty acid utilization in the hypertrophied and failing heart: molecular regulatory mechanisms. Am J Med Sci. 1999;318:36–42. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]