Abstract

Monodisperse gold nanocrystals with unique near-infrared optical properties were synthesized by simple mixing of highly shortened and well disperse single-walled carbon nanotubes and chloroauric acid in water at ambient conditions with a step-wise increase of gold ion concentration.

The development of methods for metal nanoparticle (NP) synthesis with controlled structural morphology is very important to fully exploit their size- and shape-dependent properties for a wide range of applications including catalysis, biosensing, plasmonics, and nanomedicine.1 Although there have been many attempts,1c current processes often require time-consuming and elaborate steps and limited progress has been made for high-yield production of such controlled metal nanocrystals. Recently, a unique property of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) was reported to spontaneously reduce aqueous metal ions without chemical reductants or catalysts, showing direct ways of synthesizing hybrids of metal NPS and CNTs.2 We have recently demonstrated the growth of a thin layer of gold (Au) around shortened SWNTs, in which CNTs play dual roles as substrates as well as reducing agents.3a The hybrid Au-plated SWNTs, termed golden carbon nanotubes (GNTs), have shown great promise as photoacoustic (PA) and photothermal (PT) high-contrast molecular agents with highly enhanced near-infrared (NIR) absorption contrasts and reduced toxicity.3 The demonstrated CNT’s reducing capability suggests its intriguing possibility as aqueous-phase chemical reducer to synthesize metal NPs with unique physico-chemical features and would open new avenues for addressing the significant challenges in the field of metal NP synthesis.

In this study, we introduce the unique chemical phenomenon of highly shortened SWNTs that allows crafting monodisperse nanocrystals with well-defined size and shape. The simple reaction scheme involves CNTs and metal salts in water at ambient conditions with a step-wise change of metal ion concentration. The fundamental chemistry of our approach is same as that in our recent report (i.e., direct redox reaction between metal ions and nanotubes).3a Nonetheless, the current approach distinguishes itself by further tempering CNTs’ size and their dispersity in water to synthesize monodisperse single crystalline metal NPs with better control. Also the simplicity allows large-scale production. In this research, the CNTs’ exceptional capability is confirmed using chloroauric acid (HAuCl4) and SWNTs as model compounds. Also we report unique physicochemical features of the synthesized Au nanocrystals.

The CNT size was controlled by altering the time duration for acid refluxing with sonication (ESI†).4 Surfactants, such as sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate, and others, which are usually required to improve CNTs’ aqueous dispersity, were not used in the final CNT solutions not only to alleviate any potential adversary effects (e.g., toxicity) by residual surfactants for biological and biomedical applications, but also to exclude any possibility of surfactant’s impact on NP synthesis and accurately assess CNTs’ reducing potential. Even without surfactants, our process yielded short SWNTs (average length and diameter of 29.7 ± 7.79 nm and 1.2 ± 0.19 nm, respectively) that are well dispersed in water (Fig. S1†) with the final concentration of ~ 0.1 g/L.

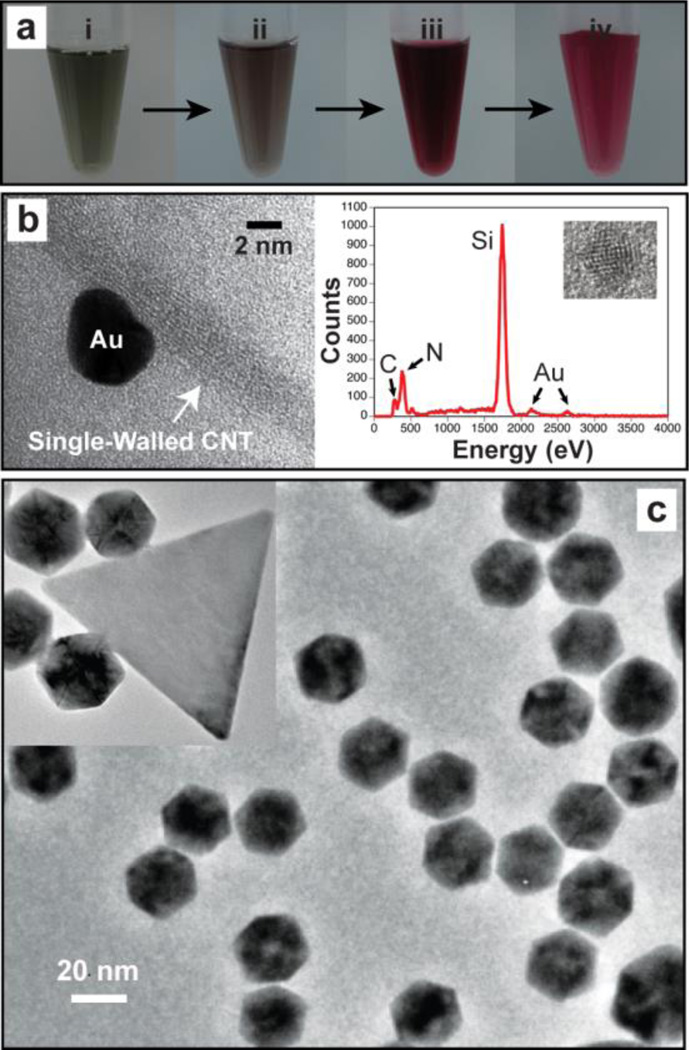

For NP synthesis, the CNT solution was sequentially subjected to two different concentrations of HAuCl4 by a step-wise increase of Au ion concentration (ESI†). Noticeably, the step-wise changes in Au ion concentration provided the same effect as the seeding-growth process, which is considered as an ideal approach to produce metal NPs with controlled size and shape.5 At the initial low AuCl4− concentration, Au ions seemingly nucleated (seeded) on nanotube surface, initiating the growth of Au. The development of light pink colour was noted after 1 h incubation at the low AuCl4− concentration (Fig. 1a-ii). The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) of the reaction solution (Fig. 1b, left) on a Si3N4 TEM membrane showed slight growths (~2–3 nm) of Au on CNT surface and the energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrum (Fig. 1b, right) indicated both Au and carbon. These evidences support Au seeding and their growth on the CNT. Upon increasing AuCl4− concentration, solution changed colour from light pink to ruby red (a typical colour of Au NP solution), indicating active Au crystal growth (Fig. 1a-iii). The resultant CNT-mediated gold NPs (cGNPs) were highly water-soluble and minimal aggregations were observed even after one month (Fig. 1a-iv). Estimated with spectrophotometery analyses, approximately 18.6% of SWNTs and 29.4% of AuCl4 yielded cGNPs (Fig. S2†). The apparent decrease of SWNT concentration after cGNP synthesis reconfirms the association of SWNTs in the Au crystal growth.

Fig. 1.

CNT-driven synthesis of monodisperse Au NPs (cGNPs). (a) Photographic images of the step-wise reaction sequences for the cGNP synthesis in water: (i) at 0 h in the presence of SWNTs and 0.2 mM HAuCl4, (ii) after 1 h incubation, (iii) after 1 h incubation with additional HAuCl4 (final concentration of 2 mM), and (iv) after washing 3 times with water. (b) HR-TEM image (left) and EDX spectrum (right) of Au nucleated on SWNT. Samples were on Si3N4 TEM membranes. (c) HR-TEM image of cGNPs after step-wise controlled crystal growth.

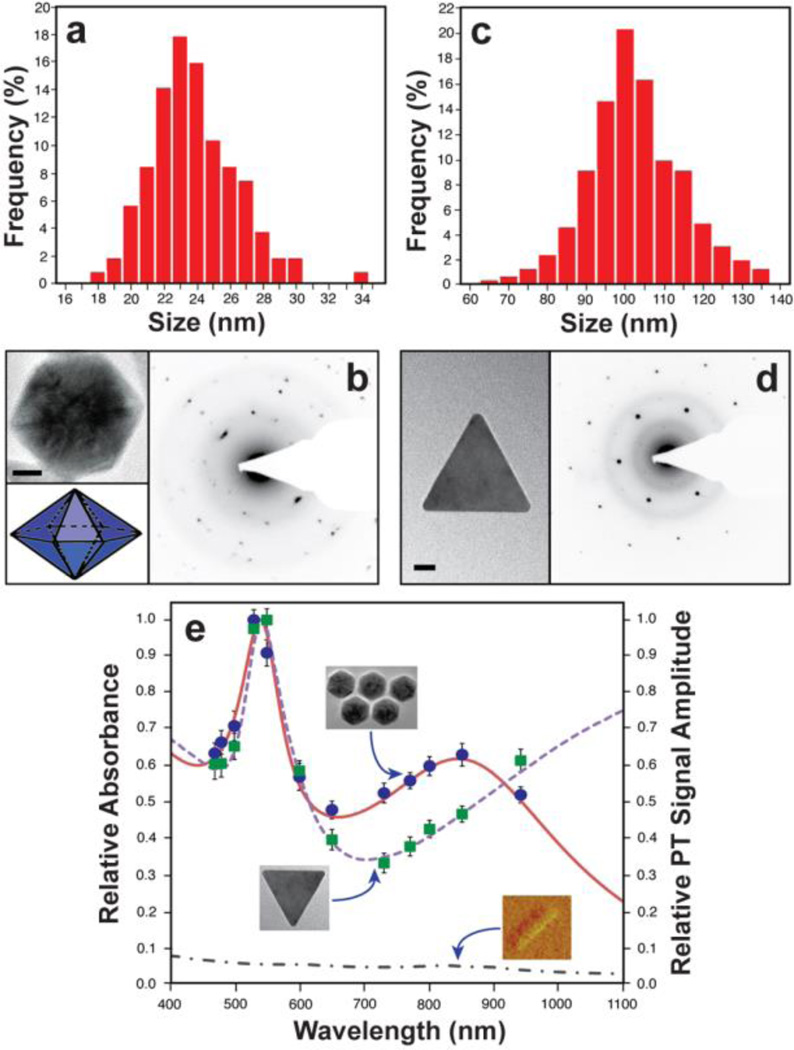

The HR-TEM images of the cGNP sample revealed the dominant formation of hexagonal bipyramidal Au NPs along with some decahedral NPs (Fig. 1c). Triangular Au NPs were also observed with a much lower density (Fig. 1c, inset). The hexagonal bipyramidal cGNPs could be easily purified by separating them through a simple size-exclusion filtering step using a commercial filtration unit (pore size, 0.1 µm), resulting in the bipyramidal cGNPs in filtrate and the majority of triangular Au NPs in retentate. The hexagonal bipyramidal NPs made up more than 90% of the overall cGNP population with average diameter of 26.6 ± 0.19 nm (Fig. 2a), and the thin, flat, triangular Au NPs made up ~ 5% with triangle edge length of 100.3 ± 4.17 nm (Fig. 2c). This not only demonstrates the excellent size- and shape-control by the CNT-driven reaction but also suggests a simple way to produce monodisperse Au NPs with different crystal forms, each of which has unique physicochemical characteristics.

Fig. 2.

Physicochemical characteristics of cGNPs after size-exclusion filtering step. (a) Size distribution of bipyramidal cGNPs. (b) SAED pattern (right) from a single bipyramidal cGNP (top left) and its 3D diagram (bottom left). (c) Size distribution of triangular cGNPs. (d) SAED pattern (right) from a single triangular cGNP (left). (e) Normalized optical spectra (left vertical axis and lines) and PT signal amplitudes (right vertical axis and symbols) of shortened SWNTs and cGNPs. Scale bars represent 10 nm (b) and 20 nm (e).

The HR-TEM image of a hexagonal bipyramidal cGNP (Fig. 2b, left) revealed that each of the six facets is not made of single crystal and apparent six-fold axis is a two-fold axis. A step-wise growth of layers of single crystals resulted in slip-lines that can be seen on facets. Main twin plane can be seen running diagonally from top left to bottom right. The selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) image (Fig. 2b, right) shows the two-fold symmetry or inversion. Despite of the complex twinning, the crystal exhibits surprisingly low mosaicity except for the diffraction spots along the twin plane. Irregular shapes suggest that the contact plane may not be perfect. The slip seen on faucets apparently occurs in a regular interval. The EDX spectrum on a Si3N4 TEM membrane shows a dominant Au peak with little carbon peak (Fig. S3†). This indicates that the SWNTs (which are the only sources of electrons for Au reduction in the reaction medium) enabled the growth of the seeded Au (Fig. 1b) on their surfaces to form the well-crafted single nanocrystals. This reconfirms the dual role of the SWNTs (i.e., seeding substrate and reducing agent). Also the Au seeding and growth on CNT surface suggests the possibility of the existence of a hollow CNT core in cGNP, although it needs further investigations. The HR-TEM imaging and diffraction analysis of triangular NPs (Fig. 2d) showed that they consist of defect-free monocrystalline Au platelets with {110} faces and {111} sides. At this point, the reasons for the formation of triangular Au NPs are unclear.

The results of the hexagonal bipyramidal cGNPs are compared with those of GNTs3a. The apparent difference between the syntheses of GNTs and cGNPs is the lengths of SWNTs in the reaction. The moderately shortened SWNTs (average length, ~100 nm) allowed multiple nucleations and growth of multiple Au NPs on their surface, resulting in the assembly of rod-shape NPs consisting of two or three linear arrays of Au NPs with minimal gaps between them as previously reported.3a But only one (or a few) seeding occurs on the highly shortened SWNTs, yielding the growth of single NPs. Also a control experiment was performed using a SWNT solution prepared to contain a mixture of highly and moderately shortened ones, i.e., ~20 – 110 nm in length (ESI†). The SWNTs with relatively large size distribution yielded the growth of both cGNPs and GNTs (Fig. S4†). More variations in the sizes of cGNPs as well as GNTs were observed due to the large variations in the sizes of SWNTs. This indicates the significance of the size uniformity of CNTs for the controlled synthesis of NPs with well-defined size and shape. Furthermore, when tested with minimally processed, long SWNTs in water (average length, > 500 nm), hybrid CNTs with isolated spherical Au NPs along their sidewalls were dominantly formed with little or no monodisperse NPs in accordance with the previous report.2b These demonstrate the CNTs’ unique size-dependent chemical feature that allows crafting nanomaterials ranging from metal CNT hybrids (by minimally processed SWNTs) to GNTs (by moderately shortened SWNTs) to single nanocrystals (by highly shortened SWNTs). Also these imply that monodisperse crystal formation could only be achieved by the highly shortened CNTs. Our CNT processing allowed overcoming the CNTs’ inherent poor processability, enabling us to explore CNTs’ unique size-dependent chemical characteristic for the synthesis of nanocrystals with control over their size and shape.

The purified hexagonal bipyramidal cGNPs after removal of triangular NPs by filtration exhibited unique surface plasmon responses (solid line in Fig. 2e) with two absorption maxima at visible region of near 525 nm (similar to spherical Au NPs) as well as in the NIR region near 900 nm (similar to Au nanorod). The triangular cGNPs showed two absorption maxima at near 525 nm and > 1100 nm (dash line in Fig. 2e). The conventional absorption spectra were in good agreement with PA and PT spectra of single Au crystals obtained with the integrated PA/PT microscope-spectrometer3a (symbols in Fig. 2e). In particular, the bipyramidal cGNPs’ plasmon resonances in the NIR were significantly higher (estimated as 25–30 fold) than those for the shortened SWNTs (dash-dot line in Fig. 2e). Of note is that such high NIR absorption is unusual for small (< 50 nm) monodisperse hexa- or deca-hedral Au NPs. Recent reports suggest negligible NIR responses of such small decahedral Au NPs although significant red shifts occur with increasing particle size (>100 nm).6 This implies that the anisotropic shape of our small hexagonal bipyramidal cGNPs (~26 nm) might not be the main source of the NIR resonances. In other words, the CNT-driven hexagonal cGNPs exhibit other structural differences to yield such unexpected plasmonic effects with high NIR responses compared to Au crystals with similar size and shape. This may be associated with the starting material, SWNTs. There may exist empty CNT cores in the bipyramidal cGNPs. The synergistic plasmonic effects of the gold shell and the empty CNT core in cGNPs may attribute to the high optical responsiveness in NIR as is the case for GNTs.3a Although it requires further clarifications, cGNPs’ distinctive NIR responses further justify the dual roles of CNTs (i.e., Au seeding templates and reducing agents) for the production of the Au nanocrystals. Furthermore, the unique surface plasmon responses of cGNPs with at least two absorption maxima suggest their potentials as multi-colour NPs.3a,b Each type of cGNPs could be used as two-colour agents considering the two distinct absorption maxima of cGNPs (Fig. 2e). Also the combination of hexagonal bipyramidal and triangular cGNPs would enable three-colour (i.e., 525 nm, 900 nm, and > 1100 nm) applications. This exemplifies the high promises of the current technology to extend the capability of the noninvasive NP-assisted technologies such as multiplex PA and PT nanodiagnostics and nanotherapeutics,3,7 whose success relies on the availability of NPs and their clusters with desirable optical properties in living systems.

In conclusion, we show for the first time that the highly shortened and well disperse SWNTs enabled controlling size and shape of highly water-soluble Au nanocrystals. The CNT-driven reaction and a subsequent simple size-exclusion separation could yield two types of monodisperse Au NPs with well-defined shape and size (i.e., hexagonal bipyramidal and triangular Au NPs). Each CNT-mediated Au NP showed very unique physicochemical characteristics, including high surface plasmon responses in the visible and near-infrared regions, implying their high potentials as multiplex optical contrast agents in biomedical applications. The reaction should work for other metal ions with reduction potentials lower than those of SWNTs, including silver, platinum, and palladium cations among many others.2a,8 Although the detailed mechanisms and the applicability to other metal NP syntheses remain to be determined, considering its simplicity, controllability, and versatility, our CNT-driven technique could be implemented to synthesize noble plasmonic metal nanocrystals with better yield and control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation awards CMMI-0709121, CCF-0523858, and DBI-0852737, the National Institute of Health awards EB000873, EB009230, EB005123, CA131164, and CA 139373, and the Arkansas Biosciences Institute. The authors thank Hee-Jeung Kim for her assistance with image processing.

Footnotes

† Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental details and Fig. S1 – S4. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Ahmadi TS, Wang ZL, Green TC, Henglein A, El-Sayed MA. Science. 1996;272:1924. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jin R, Cao YC, Hao E, Metraux GS, Schatz GC, Mirkin CA. Nature. 2003;425:487. doi: 10.1038/nature02020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xia Y, Xiong Y, Lim B, Skarabalak SE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:60. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Choi HC, Shim M, Bangsaruntip S, Dai H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9058. doi: 10.1021/ja026824t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim DS, Lee T, Geckeler KE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:104. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Kim J-W, Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Moon H-M, Zharov VP. Nature Nanotechnol. 2009;4:688. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Kelly T, Kim J-W, Yang L, Zharov VP. Nature Nanotechnol. 2009;4:855. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Galanzha EI, Kokoska MS, Shashkov EV, Kim J-W, Tuchin VV, Zharov VP. J. Biophoton. 2009;2:528. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200910046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Galanzha EI, Kim J-W, Zharov VP. J. Biophoton. 2009;2:725. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200910078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim J-W, Kotagiri N, Kim J-H, Deaton R. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;88:213110. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turkevich J, Stevenson PC. Discussions of the Faraday Society. 1951;11:55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Fernandez J, Novo C, Myroshnychenko V, Funston AM, Sanchez-Iglesias A, Pastoriza-Santos I, Perez-Juste J, de Abajo FJG, Liz-Marzan LM, Mulvaney P. J. Phys. Chem. 2009;113:18623. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zharov VP, Kim J-W, Curiel DT, Everts M. Nanomedicine. 2005;1:326. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zharov VP, Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Kim J-W, Khlebtsov NG, Tuchin VV. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007;12:051503. doi: 10.1117/1.2793746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kim J-W, Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Kotagiri N, Zharov VP. Laser Surg. Med. 2007;39:622–634. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 88th Edition. Cleveland, OH: CRC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.