Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this case report is to describe the presentation of a patient with lumbosacral chordoma characterized by somatic chronic low back pain and intermittent sacral nerve impingement.

Case report

A 69-year-old male presenting to an emergency department (ED) with low back pain was provided analgesics and muscle relaxants then referred for a series of chiropractic treatments. Chiropractic treatment included manipulation, physical therapy, and rehabilitation. After 3 times per week for a total of 4 weeks, re-examination showed little relief of his symptoms. His pain symptoms worsened and he presented to the ED for the second time. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed and revealed a high intensity mass.

Intervention and outcome

The soft tissue mass identified on magnetic resonance imaging was surgically removed. Shortly after the surgery, the patient developed post-operative bleeding and was returned to surgery. During the second procedure, he developed a post-operative hemorrhage related to the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation and subsequently died during the second procedure. A malignant lumbosacral chordoma was diagnosed on pathologic examination.

Conclusion

This case report describes the presentation of a patient with lumbosacral chordoma presenting with musculoskeletal low back pain. Chordomas are rare with few prominent manifestations. An early diagnosis can potentially make a difference in morbidity and mortality. Due to its insidious nature, it is a difficult diagnosis and one that is often delayed.

Key indexing terms: Chordoma, Chiropractic, Low back pain, Lumbosacral region

Introduction

Chordoma is a rare, slow growing neoplasm of the bone that derives from notochordal remnants.1–3 As the spine develops, notochordal remnants are downgraded to the intervertebral regions, where they progress into the nucleus pulposus3; and as a result, chordomas are almost exclusively found in the axial skeleton. Typically, chordomas tend to form in either the clivus of the skull (shallow depression behind the dorsum sellae) or the sacrococcygeal region (32% and 29% of cases respectively)4,5; the vertebral bodies are rarely involved.4,6,7

In the United States the occurrence of chordomas is approximately 1 in 1 million (approximately 300 patients a year)8 and account for less than 1% of all bone tumors.6 Chordomas of the sacral spine usually manifest themselves in the older adult, with the greatest incidence being between 50–70 years of age. Chordomas that develop at the base of the skull occur more frequently in the younger patient.6,7 Collectively, the male-to-female ratio is 2 to 3:19,10 and the median survival rate in the United States is approximately 7 years with an overall survival of 68% at 5 years and 40% at 10 years.6,7 The prognosis for patients with chordoma is, at least in part, related to how early in the disease process the correct diagnosis is made and definitive treatment undertaken.1,2 Clearly, the earlier the diagnosis is correctly made, the greater the likelihood of survival for the patient.

The clinical picture of chordomas will vary, depending on the anatomical site of the lesion. There have been published reports11,12 of patients who have a mean duration of their symptoms for 2 years before the correct diagnosis is made. Sacral chordomas, especially, can be present for a prolonged period before symptoms appear.13 Pain in the low back and sacral region is one of the most common presenting symptoms. This pain is often described as dull in nature and is usually worse in the sitting position (mimicking discogenic pain). Some patients will also develop saddle anesthesia and urinary or fecal dysfunction (cauda equina syndrome).1,2 Additionally, some patients with sacral chordomas will develop coccydynia (pain in and around the coccyx), erectile dysfunction, urinary frequency or urgency, urinary incontinence, constipation or weakness, and paresthesias of the legs.4,14,15

Although the sacral and clival regions are most commonly involved in chordoma development, these lesions may occasionally arise anywhere along the vertebral column.16 Symptoms would depend on the area involved and the local tissues that may become invaded by the disease. Chordomas are unusual tumors in that they may cause destruction after crossing a disc space. The purpose of this report is to present a case of a patient who was referred by his medical physician to a chiropractic clinic for the management and treatment of chronic lumbosacral low back pain (LBP) and was later diagnosed with lumbosacral chordoma.

Case Report

A 69-year-old male, whose medical history consists of mild, well-controlled, hypertension, presented to the emergency department (ED) complaining of a LBP for 3 to 4 months. He denied any neurological symptoms during that time, although, more recently, he had noted a few episodes of urinary incontinence and decreased urine output. Over the previous days (prior to the ED visit) he noted small amounts of urine production per day. His pain was worse when he was in a sitting position and less severe during recumbency. He had self-medicated with anti-inflammatory medications (naproxyn sodium, 2 capsules) without improvement. He had seen his primary care physician on at least 2 occasions prior to the ED visit, and was given muscle relaxants (methocarbamol 750 mg 4 times per day). When these did not help his LBP, his primary medical physician prescribed hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5 mg/300 mg every 4 hours for the pain in addition to the muscle relaxants prescribed previously. This medication improved his symptoms moderately, but only for a short period of time.

He was then referred by his primary medical physician for chiropractic care for symptomatic relief of his musculoskeletal LBP. The Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) found the physical examination findings consistent with somatic dysfunction with the exception of slight hypoesthesia over the right buttock and a very small (2 cm), palpable non-tender mass posteriorly over the sacral region. It was felt at the time that this soft tissue mass likely represented a sebaceous cyst, a small pilonidal cyst and/or Trigger Point (as described by Travell, 1999).17 Lumbopelvic radiographic images performed by both the referring medical physician and DC were unremarkable. The treatment prescribed at the chiropractic clinic included a variety of mobilization and manipulation therapies (VibraCussor, Sound-assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization, Instrument-Assisted joint manipulation, and mild distraction to the L5-SI joint via Cox protocol) to hypo-mobile joints (with emphasis on the sacral-iliac and lumbosacral junction). Other adjunctive therapies prescribed and performed by the DC included various physical therapy techniques (including pelvic and abdominal strengthening exercises) and nutritional consultation (anti-inflammatory dietary recommendation). The described treatment protocol was 3 times per week for a total of 4 weeks, with the aim of reducing pain. Upon re-examination, he described little, if any, permanent relief of his symptoms. At this point his pain symptoms had worsened so he presented to the ED for the second time to decrease his LBP pain.

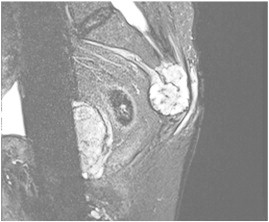

The physical examination findings in the second ED visit confirmed the objective findings noted in the chiropractic report. However, the small non-tender palpable mass, together with the finding of hypoesthesia and failure to respond to multiple conservative treatment modalities led to the order of an emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination of the lumbosacral spine region. Following the MRI showed a moderately sized mass within the sacrum (anterior surface). The radiologist noted that the images were suspicious for a chordoma (Fig 1), but stated that other types of mass would be included in the differential diagnosis. A differential diagnosis should be established with multiple myeloma, chondrosacrcoma, giant cell tumor, spinal metastases and/or spinal lymphoma. Additionally, chordomas are always radiolucent on radiographs and may show cortical destruction and poor margination; yet, in most cases, only a tumorous destructive space occupation can be depicted with the help of radiological examination. Specific diagnostic MRI features or radiological signs of the chordoma are not known. The diagnosis may only be secured by a biopsy of the tumor.

Fig 1.

T2-weighted sagittal MRI of the sacrum with a chordoma. Sagittal MR image shows a heterogeneously hyperintense sacral mass with a presacral soft-tissue component.

After the diagnosis was confirmed the patient was taken to the operating room for surgical excision of the tumor. Shortly after the surgery ended, he developed post-operative bleeding and was returned to surgery in an attempt to stop the bleeding. During this second procedure he developed a post-operative hemorrhage related to the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and subsequently died during the second procedure.

Discussion

Chordoma is a rare, slow-growing neoplasm, and part of the sarcoma family which includes cancers of bone, cartilage, muscle and other connective tissue.18 Understanding the development of the embryonic spinal cord is essential in comprehending the formation of a chordoma. The formation of the embryonic neural tube gives rise to the development of the embryonic spinal cord as a result of 3 distinct processes (gastrulation, notogenesis and neurolation). During the third week of gestation the process of gastrulation takes place.19 At this time, migration of cells deep into the neural tube takes place forming the endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. These cells will then form the embryonic tissues and organs. The ectoderm will develop into the skin and nervous system. The migration of cells takes place into the fourth week of gestation. Notogenesis is the second process in the development of the spinal tube and during notogenesis the notochord formation takes place by way of the epiblast found in the amnion cavity.20 The notochord is a flexible rod along the dorsal aspect of the embryo which is a primitive representation of the early spine during the early development of the fetus. During the third week of gestation the notochord will send a signal to the ectoderm via secretions of the sonic hedgehog (a protein responsible for tissue differentiation and formation).21 The notochord is essential as a signaling pathway and it is a transient structure during the development of the vertebrae nervous system. The notochord is not found in the adult organism and this notochord will stimulate the next process of neurolation in the ectoderm. This process spans well into the fourth week of gestation, and neurolation is the third process responsible for beginning the formation of the vertebrate nervous system in the embryo. The embryonic ectoderm, or neuroectoderm, will form neuronal stems cell that will lead to the development of the neuronal plate. The folding and fusion of the ectoderm will then lead to the formation of the spine.22,23 After the migration of cells and fusion of vertebral structures the notochord will signal the beginning of the ossification process. The notochord will then begin to regress and separate from the endoderm. By the age of 4 years, the notochord will be replaced by chondrocyte cells.19,22,23

A chordoma may occur if microscopic notochordal foci cells do not degenerate and are lodged, and left behind. The most common location for this to occur is the clivus which supports the pons and basilar artery and sacrococcygeal. Malignant transformation, which is relatively rare, takes place from the notochord and chordomas can form. Other areas where chordoma formation can occur are the transverse processes of the vertebras and the paranasal sinuses. Chordomas are classified as malignant, frequently recur even after excision, and may metastasize, although this is rare. Chordomas are classified as a low grade malignancy because they are relatively slow growing and may lay dormant for decades. They are more likely to recur locally rather than spreading throughout the body.19,22,23

There are numerous processes which can cause low back or neck pain, and such symptoms are ubiquitous within the population. Admittedly, only a very small percentage of patients with symptoms referable to these areas will ultimately be diagnosed with chordoma. However, considering the possibility of chordoma, especially in those patients who fail to respond to common treatments for their back or neck pain early on, may assist in accelerating the diagnosis of this condition. When we consider that some patients have symptoms for 2 or more years prior to diagnosis, we can appreciate that an earlier diagnosis of chordoma will aid in decreasing the morbidity and mortality of this disease.

It would be erroneous to assume that people with back or neck pain only have musculoskeletal issues, such as muscle spasm, radiculopathy or herniated discs. This case presentation reminds us that patients may have a more serious condition, potentially having an adverse effect on their quality of life and survival, and this should not be overlooked. Delayed diagnosis has a negative impact on long-term survivability and quality of life, thus early detection is encouraged.

Limitations

The retrospective case analysis is subjected to the global limitations inherent of case reporting. The findings are unique to the patient and may not necessarily be extrapolated to others. Furthermore, the authors were unable to gain access to all medical record as they were purged 5 years after the patient deceased. Digital copies of MRI were provided by health care institutions from which the patient received terminal care.

Conclusion

Chordomas are rare with few prominent manifestations. An early diagnosis can potentially make a difference in morbidity and mortality. Due to its insidious nature, it is a difficult diagnosis and one that is often delayed.

This elderly male patient, who was previously asymptomatic, developed low back pain and difficulty with urination. Initial consideration of the case resulted in consideration of possible diagnoses from prostate cancer to possible sequela from an old back injury from a work incident. After advanced imaging was obtained, a chordoma was considered. Creating a broad differential diagnosis list should be emphasized in chiropractic practice and that red flags (unresponsive LBP to conservative care, coupled with urinary bowel/bladder symptoms) should be considered.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References

- 1.Conforti R., Sardaro A., Tecame M. Chordoma: Diagnostic considerations and review of the literature. Recenti Prog Med. 2013;104(7-8):322–327. doi: 10.1701/1315.14569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams B.J., Raper D.M., Godbout E. Diagnosis and treatment of chordoma. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2013;11(6):726–731. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphey M.D., Andrews C.L., Flemming D.J., Temple H.T., Smith W.S., Smirniotopoulos J.G. From the archives of the AFIP. primary tumors of the spine: Radiologic pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1996;16(5):1131–1158. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.16.5.8888395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farsad K., Kattapuram S.V., Sacknoff R., Ono J., Nielsen G.P. Sacral chordoma. Radiographics. 2009;29(5):1525–1530. doi: 10.1148/rg.295085215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llauger J., Palmer J., Amores S., Bague S., Camins A. Primary tumors of the sacrum: Diagnostic imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(2):417–424. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.2.1740417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMaster M.L., Goldstein A.M., Bromley C.M., Ishibe N., Parry D.M. Chordoma: Incidence and survival patterns in the united states, 1973-1995. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12(1):1–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1008947301735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanzino G., Dumont A.S., Lopes M.B., Laws E.R., Jr. Skull base chordomas: Overview of disease, management options, and outcome. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10(3):E12. doi: 10.3171/foc.2001.10.3.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y., Xiao J., Wu Z. Primary chordomas of the cervical spine: A consecutive series of 14 surgically managed cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17(4):292–299. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.SPINE12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber S., Ollivier L., Leclere J. Imaging of sacral tumours. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(4):277–289. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikoghosyan A.V., Karapanagiotou-Schenkel I., Munter M.W., Jensen A.D., Combs S.E., Debus J. Randomised trial of proton vs. carbon ion radiation therapy in patients with chordoma of the skull base, clinical phase III study HIT-1-study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:607. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-607. [2407-10-607] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Localio S.A., Eng K., Ranson J.H. Abdominosacral approach for retrorectal tumors. Ann Surg. 1980;191(5):555–560. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198005000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riopel C., Michot C. Chordomas. Ann Pathol. 2007;27(1):6–15. doi: 10.1016/s0242-6498(07)88679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wurtz L.D., Peabody T.D., Simon M.A. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of primary bone sarcoma of the pelvis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(3):317–325. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emerson S.S., Speece A.J., III Manipulation of the coccyx with anesthesia for the management of coccydynia. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112(12):805–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woon J.T., Perumal V., Maigne J.Y., Stringer M.D. CT morphology and morphometry of the normal adult coccyx. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(4):863–870. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2595-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coppens J.R., Ric Harnsberger H., Finn M.A., Sharma P., Couldwell W.T. Oronasopharyngeal chordomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009;151(8):901–907. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Travell J., Simons D., Simons L. Lippincott Williams & Williams; USA: 1999. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: The trigger point manual. [2 vol. set, 2nd Ed.] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romeo S., Dei Tos A.P. Soft tissue tumors associated with EWSR1 translocation. Virchows Arch. 2010;456(2):219–234. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan K.M., Spivak J.M., Bendo B.A. Embryology of the spine and associated congenital abnormalities. Spine J. 2005;5:564–576. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagercrantz H., Ringstedt T. Organization of the neuronal circuits in the central nervous system during development. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90(7):707–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jambhekar N.A., Rekhi B., Thorat K., Dikshit R., Agrawal M., Puri A. Revisiting chordoma with brachyury, a “new age" marker: Analysis of a validation study on 51 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(8):1181–1187. doi: 10.5858/2009-0476-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazary A., Bors I.B., Szoverfi Z., Ronai M., Varga P.P. Prognostic factors of primary spinal tumors. Ideggyogy Sz. 2012;65(5–6):161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng E.Y., Ozerdemoglu R.A., Transfeldt E.E., Thompson R.C., Jr. Lumbosacral chordoma. prognostic factors and treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24(16):1639–1645. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199908150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]