Abstract

Background: Autoimmune thyroid diseases (AITDs) predominantly develop in females. One of two X chromosomes is randomly inactivated by methylation in each female cell, but it has been reported that skewed X chromosome inactivation (XCI) may be associated with the development of autoimmune diseases. To clarify the significance of skewed XCI in the prognosis and development of AITD, we investigated the proportion of skewed XCI in female patients with AITD.

Methods: We analyzed the degree of XCI skewing in 120 female patients with AITD (77 patients with Graves' disease [GD] and 43 patients with Hashimoto's disease [HD]) and 49 female controls in DNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). We performed XCI analysis by digesting inactive DNA with a methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme (HpaII) followed by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for the polymorphic CAG repeat of the androgen receptor gene and electrophoresis of the PCR products.

Results: The proportion of skewed XCI (≥65% skewing) was not significantly different between AITD patients and control subjects but was higher in patients with intractable GD (66.7%) than those with GD in remission (25.0%, p=0.0033) and control subjects (32.6%, p=0.0038). When the cutoff value for XCI skewing was relaxed, the proportion of skewed XCI (≥60% skewing) was higher in patients with severe HD (76.5%) than in those with mild HD (41.2%, p=0.0342).

Conclusions: Skewed XCI is related to the prognosis of AITD, particularly the intractability of GD.

Introduction

Graves' disease (GD) and Hashimoto's disease (HD) are autoimmune thyroid diseases (AITD) that involve the breakdown of self-tolerance (1,2). The etiologic factors for the development and prognosis of AITD are not fully understood. The intractability of GD and severity of HD vary between patients. Some patients with GD achieve remission with medical treatment, and others do not. Some patients with HD develop hypothyroidism during early life, but others remain in a euthyroid state in old age despite the passage of time. It is difficult to predict the prognosis of AITD.

Autoimmune diseases, particularly AITD, are more common in females. The ratio of the incidence of autoimmune diseases between females and males is approximately 9:1 (3). This phenomenon may be due to the difference in sex hormone levels, such as estrogen (4). Recently, X chromosomes have been reported to be another factor for this disparity (5) because the X chromosome contains many genes related to the immune response, including forkhead box P3 (FOXP3), CD40 ligand (CD40L), and Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) (5–7).

Unlike males, who have only one X chromosome, females possess one X chromosome that is maternally inherited and one that is paternally inherited. To balance the gene expression copy number between females and males, in humans, one of the two X chromosomes in each female cell inherited from the mother or father is randomly inactivated by methylation. Thus, females comprise two cell populations, including cells with inactivated maternal X chromosomes and those with inactivated paternal X chromosomes. In some females, however, this inactivation can predominantly occur to either the maternal or paternal X chromosome (8,9). This phenomenon is referred to as skewed X chromosome inactivation (XCI). Previous studies have indicated that skewed XCI is associated with the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, such as AITD (10,11), rheumatoid arthritis (12), and scleroderma (13).

In this study, we investigated the association between skewed XCI and the prognosis and development of AITD.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

In this study, 77 patients with GD, 43 patients with HD, and 49 healthy controls were enrolled. All of the subjects were Japanese females and unrelated. We categorized the GD patients who had a clinical history of thyrotoxicosis with elevated levels of antithyrotropin receptor antibody (TRAb) as follows: 45 patients with intractable GD who were treated with methimazole for at least five years and remained positive for TRAb, and 32 patients with GD in remission who had maintained a euthyroid state and were negative for TRAb for more than two years without medication. We also categorized the HD patients who were positive for antithyroid microsomal antibody (McAb) and/or antithyroglobulin antibody (TgAb) into the following groups: 20 patients with severe HD who developed moderate to severe hypothyroidism before 50 years of age and were treated daily with thyroxine, and 23 patients with mild HD who were untreated and euthyroid over 50 years of age. The healthy controls had no clinical history of autoimmune disease, were euthyroid, and were negative for thyroid autoantibodies. The clinical characteristics of each group of AITD patients are shown in Table 1. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka University.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Each Group of AITD Patients

| GD | HD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of the past clinical history of thyrotoxicosis with elevated TRAb | Presence of the diffuse goiter and the positive TgAb and/or McAb | ||||

| Controls | Intractable | In remission | Severe | Mild | |

| N | 49 | 45 | 32 | 20 | 23 |

| Age at sampling (years) | 45.1±17.7 | 45.9±14.5 | 46.6±14.1 | 47.5±14.8 | 61.1±9.9 |

| Range | 21–82 | 25–82 | 28–79 | 23–73 | 50–92 |

| Goiter size (cm) | ND | 5.35±1.35* | 4.39±0.66 | 4.15±0.95 | 4.51±1.08 |

| fT4 (ng/dL) | 1.23±0.46 | 1.19±0.30 | 1.24±0.15 | 1.37±0.31 | 1.21±0.20 |

| fT3 (pg/mL) | 2.37±0.55 | 2.69±0.40 | 2.60±0.37 | 2.75±0.57 | 2.93±0.28 |

| TSH (μU/mL) | 1.76±2.26 | 1.62±1.28 | 2.08±1.36 | 1.54±1.08 | 2.91±1.88 |

| TRAb (IU/L) | <2.0 | 7.87±14.29 | <2.0 | <2.0 | <2.0 |

| TgAb (2n×100) | Negative | 2.72±3.13 | 2.00±1.63 | 11.0±1.41† | 2.66±3.50 |

| McAb (2n×100) | Negative | 5.29±2.73 | 4.29±2.14 | 4.67±4.13 | 4.40±4.56 |

| Current treatment | None | MMI or PTU | None | L-thyroxine | None |

| Treatment time (years) | None | 13.0±6.5 | 3.4±1.2b | 11.5±7.22 | None |

| Current dose of antithyroid drug (mg/day)a | None | 18.6±33.6 | None | None | None |

| Range | 2.5–150 | ||||

| Current dose of L-thyroxine (μg/day) | None | None | None | 80.4±30.0 | None |

| Range | 50–150 | ||||

Results are mean±standard deviations.

Doses were expressed by the comparable dose of MMI (50 mg of PTU was converted to 5 mg of MMI).

Duration of the treatment with antithyroid drug before remission.

p<0.05 vs. GD in remission; †p<0.05 vs. mild HD.

AITD, autoimmune thyroid disease; GD, Graves' disease; HD, Hashimoto's disease; NS, not significant; ND, not determined; fT4, free thyroxine; fT3, free triiodothyronine; TSH, thyrotropin; TRAb, antithyrotropin receptor antibody; McAb, antithyroid microsomal antibody; TgAb, antithyroglobulin antibody; MMI, metimasol; PTU, propylthiouracil.

Method

Genomic DNA isolation

Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes, and genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) using commercial kits (Dr.GenTLE™; Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan; and Quick gene SP kit DNA Whole Blood; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Detection of inactivated gene

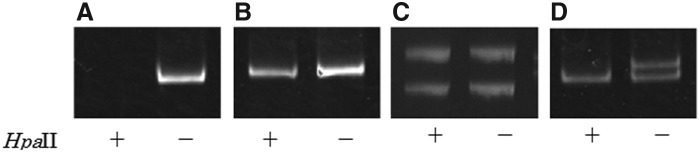

Isolated DNA was digested with the methylation sensitive restriction enzyme HpaII (New England BioLabs, Inc., Beverly, NA) to obtain polymerase chain reaction (PCR) templates. All samples were incubated for 2 h at 37°C for digestion and heat inactivated for 5 min at 65°C. To evaluate the level of inactivated X chromosomes, we amplified the CAG repeat region in the first exon of androgen receptor (AR) gene using PCR (13,14). The sequence of the forward primer was 5′-GCT GTG AAG GTT GCT GTT CCT CAT-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-TCC AGA ATC TGT TCC AGA GCG TGC-3′ (14). PCR conditions were as follows: 5 min at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 70°C, and 30 sec at 72°C. The annealing temperature was 70°C for the first cycle, and it was decreased 0.8°C per cycle until it reached 53°C where it was maintained for the subsequent cycles. PCR products were electrophoresed in 8% (acrylamide/bisacrylamide 19:1) denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis was run for 120 min at 250 V. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under ultraviolet light. Each PCR product was then detected from maternally and paternally inherited X chromosomes using the difference in each CAG repeat number. We also used a DNA sample from a male control as a digestion control because male X chromosomes are unmethylated. PCR products from undigested male DNA appear as a single band, while male DNA does not have bands when the DNA is completely digested with HpaII (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Representative examples of the electrophoretic pattern. (A) Male control (digestion control; polymerase chain reaction [PCR] products from undigested DNA appear as a single band, while PCR products from digested DNA does not have bands, this shows DNA is completely digested with HpaII). (B) Excluded sample (could not distinguish two bands of undigested PCR products because two alleles from the maternally and paternally inherited CAG repeats were the same). (C) Not skewed (degree of X chromosome inactivation [XCI] skewing: 55.3%). (D) Skewed (degree of XCI skewing: 88.2%). Lane: + and − indicate undigestioned and digestion by HpaII, respectively.

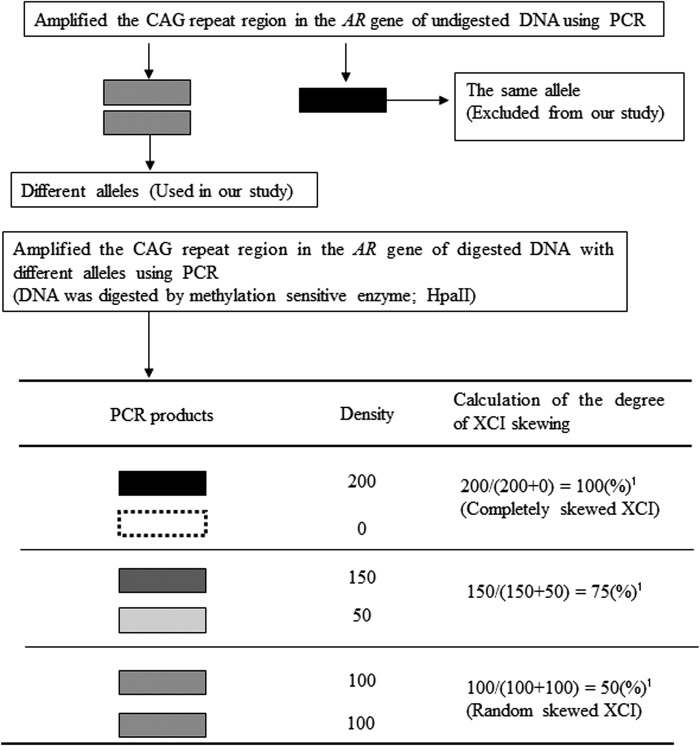

Quantitative analysis of XCI

XCI skewing was determined as shown in Figure 2. When we could not distinguish two bands of PCR products from undigested DNA, we determined that the two alleles from the maternally and paternally inherited CAG repeats were identical, and these samples were excluded from our analysis (Fig. 1B). Next, using PCR products from digested DNA samples with different alleles, the degree of XCI was calculated by the densities of two bands in a polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1C and D). Quantitative analysis was performed with densitometry using software ImageJ (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Briefly, we measured the density of each band derived from the two alleles (the A allele and B allele) with background adjustment. The degree of XCI skewing was calculated as follows:

|

FIG. 2.

Measuring procedure for the degree of XCI skewing. Black band shows high density of PCR products, and white band shows low density of PCR products. 1Degree of XCI skewing=density of A allele/(density of A allele+density of B allele). (The allele with relatively stronger density was determined to be the A allele.)

(The allele with relatively stronger density was determined to be the A allele.)

The degree of XCI skewing varies between 50% and 100%, where 50% and 100% reflect random and completely skewed XCI, respectively.

Thyroid function and autoantibodies

The serum concentrations of free thyroxine (fT4), free triiodothyronine (fT3), and thyrotropin (TSH) were measured using ECLIA (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The reference ranges of serum fT4, fT3, and TSH were 0.9–1.7 ng/dL, 2.3–4.3 pg/mL, and 0.5–5.0 μU/mL, respectively. TgAb and McAb were measured using a particle agglutination kit (Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan). A reciprocal titer >1:100 was considered positive. At the onset, the serum TRAb was routinely measured using a radioreceptor assay and a commercial kit (Cosmic Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Serum TRAb at sampling was determined using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA; third-generation; Roche Diagnostics Ltd.). Normal TRAb values were <10% as determined by a radioreceptor assay and 2.0 IU/L by ECLIA.

Statistical analysis

We used the chi square and Fisher's exact tests to evaluate the significance of differences in the frequency of individuals with skewed XCI among the groups. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to analyze differences in the serum titer of the McAb, TgAb, and TRAb levels. Data were analyzed with the JMP 10 software (SAS Institute Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Probability values of <0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

XCI status

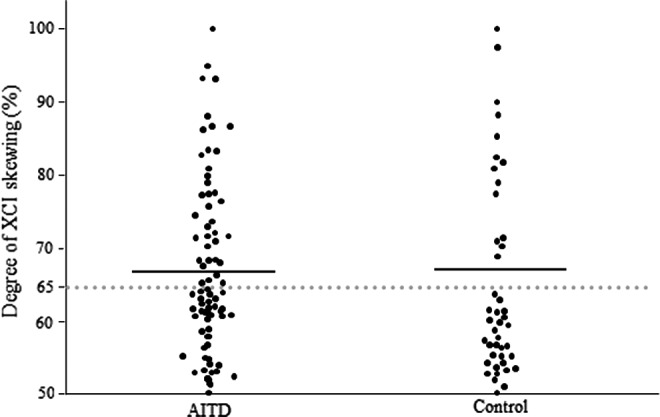

Individuals who have the same alleles were excluded from this study. Thus, the degree of XCI skewing was measured in 30 of 45 patients with intractable GD, 20 of 32 patients with GD in remission, 17 of 20 patients with severe HD, 17 of 23 patients with mild HD, and 43 of 49 control subjects. The degree of XCI skewing in all AITD patients and controls is shown in Figure 3. There was no difference in the mean degree of XCI skewing between patients with AITD and control subjects (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Degree of XCI skewing in autoimmune thyroid disease and control subjects.

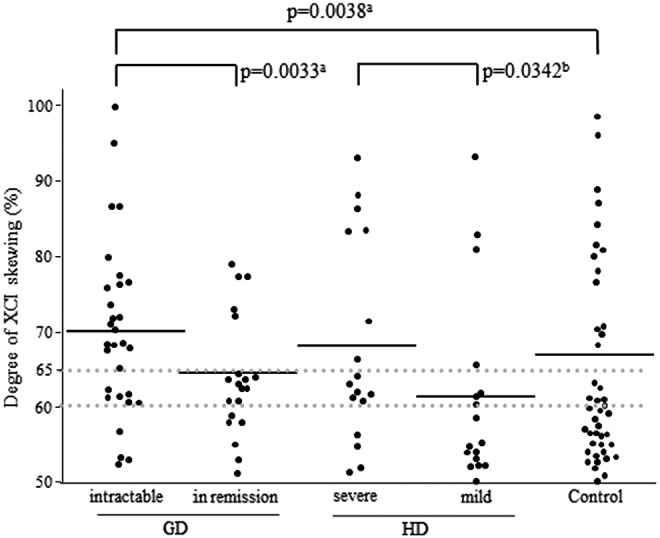

The degree of XCI skewing for the GD patients, HD patients, and controls is shown in Figure 4. There was no significant difference in the mean degree of XCI skewing for each group.

FIG. 4.

Degree of XCI skewing in the Graves' disease, Hashimoto's disease, and control groups. aSkewed XCI (≥65% skewing); bskewed XCI (≥60% skewing). NS, not significant.

Proportion of XCI status

There was no significant difference in the proportion of individuals with skewed XCI (≥65% skewing) between patients with AITD and control subjects or even between each of the GD and HD patients and control subjects (Table 2). In contrast, the proportion of intractable GD patients (66.7%) with skewed XCI (≥65% skewing) was significantly higher than that of patients with GD in remission (25.0%, p=0.0033) and that of control subjects (32.6%, p=0.0038; Fig. 4). There was no difference in the proportion of individuals with skewed XCI (≥65% skewing) between patients with severe HD and those with mild HD. However, when the cutoff value for XCI skewing was relaxed, the proportion of skewed XCI (≥60% skewing) was higher in patients with severe HD (76.5%) than in those with mild HD (41.2%, p=0.0342; Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Proportion of Skewed XCI in AITD Patients

| AITD | GD | HD | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=84) | p-Value | (n=50) | p-Value | (n=34) | p-Value | (n=43) | |

| Skewed (≥65%) | 36 (42.9) | NSa | 25 (50.0) | NSa | 11 (32.4) | NSa | 14 (32.6) |

| Not skewed (<65%) | 48 (57.1) | 25 (50.0) | 23 (67.6) | 29 (67.4) | |||

Values are the number (%).

Analyzed by chi-square test. avs. control.

XCI, X chromosome inactivation.

Clinical characteristics and XCI status

We found no association between any of the clinical characteristics (age at the time of sampling, fT4, fT3, TSH, TRAb, TgAb, and McAb) and XCI status. We also analyzed the association between XCI skewing and goiter size in GD patients, but there was no significant association (n=50, r=0.15).

FOXP3 polymorphisms and XCI status

We previously reported that the functional polymorphisms (rs3761548 C/A and rs3761549 C/T) in the FOXP3 gene, which is located on the X chromosome, are associated with intractable GD (15). Therefore, we analyzed the XCI skewing among different FOXP3 polymorphisms. However, there were no significant differences in the degree of XCI skewing among the genotypes (rs3761548C/A: CC, n=79, 66.8±12.2%; CA, n=14, 66.0±9.9%; AA, n=4, 60.6±15.5%; rs3761549C/T: CC, n=70, 64.9±11.3%; CT, n=31, 70.1±14.6%; TT, n=8, 68.5±9.7%). Combined analysis of XCI skewing and FOXP3 polymorphisms did also not show any significant relation to the susceptibility and intractability of GD.

Discussion

There is no clear consensus for the definition of skewed XCI. Previous studies have used various cutoffs of XCI skewing (65–90%) to define skewed XCI (10–12,16–18). In this study, the degree of XCI skewing in control subjects showed a bimodal distribution and could be assigned to two groups: <65% and >65% XCI skewing (Figs. 3 and 4). We therefore have defined XCI with ≥65% skewing as skewed XCI.

The proportion of intractable GD patients with skewed XCI was significantly higher than that of patients with GD in remission and controls (Fig. 4). This finding suggests that skewed XCI is related to the intractability of GD. The reason is unknown, but it was previously reported that cell growth may be one of the causes of skewed XCI (19,20). Therefore, strong cell growth of Th17 cells, which are predominantly increased in intractable GD (21), might occur in intractable GD. Moreover, the X chromosome contains many immune-related genes such as FOXP3, CD40L, and TLR7 (7,22), and we previously reported that functional polymorphisms in FOXP3 and CD40 genes, which encodes the receptor for CD40L, are also associated with intractable GD (15,23). Combined analysis of XCI skewing and FOXP3 polymorphisms did not show any significant relation to the susceptibility and intractability of GD. It is important to compare the degree of XCI skewing and the expressions of FOXP3 and CD40 in the future.

Furthermore, a locus on Xq21.33–22 links to GD but not to HD (24). This locus contains the gene involved in the pathogenesis of X-linked agammaglobulinemia, that is, Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), and many additional genes. Therefore, the expression of this locus may be affected by skewed XCI and involved in the intractability of GD. Supporting this hypothesis, other studies also reported that the proportion of skewed XCI was significantly higher in GD patients than controls but not in HD patients than controls (11), and the proportion of skewed XCI was higher in GD than HD patients (12). However, we found no associations between TRAb levels and skewed XCI, probably because TRAb levels do not reflect the intractability of GD but the activity of GD.

In addition, when we set the cutoff value for XCI skewing to 60%, the proportion of skewed XCI was significantly higher for severe HD patients than mild HD patients. This result suggests that skewed XCI may be also associated with the severity of HD.

In contrast, in this study, there was no significant difference in the degree of XCI skewing between AITD patients and control subjects (Fig. 3). However, in Caucasians, the degree of XCI skewing for AITD patients was significantly higher than that for controls (10,11,25,26). Interestingly, the proportion of control subjects with skewed XCI in this study was higher than in Caucasian studies (10,11,25) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, in Asian (Japanese and Korean), Indian, and Caucasian (Tunisian and Turkish) studies, the proportion of healthy controls with skewed XCI was also high and similar to that found in this study (12,27–30). Therefore, there may be ethnic differences in the frequency of individuals with skewed XCI.

It has been hypothesized that skewed XCI could be a factor that influences the female predisposition to autoimmunity (31). We did not find a difference in the proportion of skewed XCI between AITD patients and control subjects, but found that the proportion of skewed XCI was higher in intractable GD patients than GD patients in remission. This finding indicates that skewed XCI is not related to the development of AITD but is related to the prognosis of AITD, particularly the intractability of GD.

A limitation of this study is the fact that imbalanced X inactivation can be tissue- and age-dependent (32). Since we analyzed skewed XCI in PBMC, this study only reflects the imbalance of X inactivation in PBMC at a given time point, but not in thyroidal infiltrating cells. It may be important to compare the degree of XCI skewing in thyroidal infiltrating cells in the future.

In conclusion, skewed XCI is not related to the development of AITD, but it is related to the prognosis of AITD, particularly the intractability of GD. This is the first study showing an association between skewed XCI and the prognosis of AITD.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Menconi F, Oppenheim YL, Tomer Y.2008Graves' disease. In: Shoenfeld Y, Cervera R, Gershwin ME. (eds) Diagnostic Criteria in Autoimmune Diseases. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 231–235 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weetman AP.2000Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. In: Braverman LE, Utiger R. (eds) The Thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, pp 721–732 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockshin MD.2006Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Lupus 15:753–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutolo M, Capellino S, Sulli A, Serioli B, Secchi ME, Villaggio B, Straub RH.2006Estrogens and autoimmune diseases. Ann NY Acad Sci 1089:538–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selmi C.2008The X in sex: how autoimmune diseases revolve around sex chromosomes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 22:913–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks WH.2010X chromosome inactivation and autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 39:20–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Libert C, Dejager L, Pinheiro I.2010The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nature Rev Immunol 10:594–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon MF.1961Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L.). Nature 190:372–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monk M, Grant M.1990Preferential X-chromosome inactivation, DNA methylation and imprinting. Dev Suppl:55–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozcelik T, Uz E, Akyerli CB, Bagislar S, Mustafa CA, Gursoy A, Akarsu N, Toruner G, Kamel N, Gullu S.2006Evidence from autoimmune thyroiditis of skewed X-chromosome inactivation in female predisposition to autoimmunity. Eur J Hum Genet 14:791–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brix TH, Knudsen GP, Kristiansen M, Kyvik KO, Orstavik KH, Hegedus L.2005High frequency of skewed X-chromosome inactivation in females with autoimmune thyroid disease: a possible explanation for the female predisposition to thyroid autoimmunity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:5949–5953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chabchoub G, Uz E, Maalej A, Mustafa CA, Rebai A, Mnif M, Bahloul Z, Farid NR, Ozcelik T, Ayadi H.2009Analysis of skewed X-chromosome inactivation in females with rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune thyroid diseases. Arthritis Res Ther 11:R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozbalkan Z, Bagislar S, Kiraz S, Akyerli CB, Ozer HT, Yavuz S, Birlik AM, Calguneri M, Ozcelik T.2005Skewed X chromosome inactivation in blood cells of women with scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum 52:1564–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen RC, Zoghbi HY, Moseley AB, Rosenblatt HM, Belmont JW.1992Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen-receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am J Hum Genet 51:1229–1239 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue N, Watanabe M, Morita M, Tomizawa R, Akamizu T, Tatsumi K, Hidaka Y, Iwatani Y.2010Association of functional polymorphisms related to the transcriptional level of FOXP3 with prognosis of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 162:402–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busque L, Mio R, Mattioli J, Brais E, Blais N, Lalonde Y, Maragh M, Gilliland DG.1996Nonrandom X-inactivation patterns in normal females: lyonization ratios vary with age. Blood 88:59–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uz E, Mustafa C, Topaloglu R, Bilginer Y, Dursun A, Kasapcopur O, Ozen S, Bakkaloglu A, Ozcelik T.2009Increased frequency of extremely skewed X chromosome inactivation in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 60:3410–3412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manzardo AM, Henkhaus R, Hidaka B, Penick EC, Poje AB, Butler MG.2012X chromosome inactivation in women with alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36:1325–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown CJ.1999Skewed X-chromosome inactivation: cause or consequence? J Natl Cancer Inst 91:304–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medema RH, Burgering BM.2007The X factor: skewing X inactivation towards cancer. Cell 129:1253–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanba T, Watanabe M, Inoue N, Iwatani Y.2009Increases of the Th1/Th2 cell ratio in severe Hashimoto's disease and in the proportion of Th17 cells in intractable Graves' disease. Thyroid 19:495–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng J, Deng J, Jiang L, Yang L, You Y, Hu M, Li N, Wu H, Li W, Li H, Lu J, Zhou Y.2013Heterozygous genetic variations of FOXP3 in Xp11.23 elevate breast cancer risk in Chinese population via skewed X-chromosome inactivation. Hum Mutat 34:619–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue N, Watanabe M, Yamada H, Takemura K, Hayashi F, Yamakawa N, Akahane M, Shimizuishi Y, Hidaka Y, Iwatani Y.2012Associations between autoimmune thyroid disease prognosis and functional polymorphisms of susceptibility genes, CTLA4, PTPN22, CD40, FCRL3, and ZFAT, previously revealed in genome-wide association studies. J Clin Immunol 32:1243–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbesino G, Tomer Y, Concepcion ES, Davies TF, Greenberg DA.1998Linkage analysis of candidate genes in autoimmune thyroid disease. II. Selected gender-related genes and the X-chromosome. International Consortium for the Genetics of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:3290–3295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin X, Latif R, Tomer Y, Davies TF.2007Thyroid epigenetics: X chromosome inactivation in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1110:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simmonds MJ, Kavvoura FK, Brand OJ, Newby PR, Jackson LE, Hargreaves CE, Franklyn JA, Gough SC.2014Skewed X chromosome inactivation and female preponderance in autoimmune thyroid disease: an association study and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:E127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon SH, Choi YM, Hong MA, Kang BM, Kim JJ, Min EG, Kim JG, Moon SY.2008X chromosome inactivation patterns in patients with idiopathic premature ovarian failure. Hum Reprod 23:688–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JW, Park SY, Kim YM, Kim JM, Han JY, Ryu HM.2004X-chromosome inactivation patterns in Korean women with idiopathic recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Korean Med Sci 19:258–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aruna M, Dasgupta S, Sirisha PV, Andal Bhaskar S, Tarakeswari S, Singh L, Reddy BM.2011Role of androgen receptor CAG repeat polymorphism and X-inactivation in the manifestation of recurrent spontaneous abortions in Indian women. PLoS One 6:e17718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato K, Uehara S, Hashiyada M, Nabeshima H, Sugawara J, Terada Y, Yaegashi N, Okamura K.2004Genetic significance of skewed X-chromosome inactivation in premature ovarian failure. Am J Med Genet A 130A:240–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozcelik T.2008X chromosome inactivation and female predisposition to autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 34:348–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharp A, Robinson D, Jacobs P.2000Age- and tissue-specific variation of X chromosome inactivation ratios in normal women. Hum Genet 107:343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]