Abstract

Risk factors contributing to institutionalization after inpatient rehabilitation for people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) have not been well studied and need to be better understood to guide clinicians during rehabilitation. We aimed to develop a prognostic model that could be used at admission to inpatient rehabilitation facilities to predict discharge disposition. The model could be used to provide the interdisciplinary team with information regarding aspects of patients' functioning and/or their living situation that need particular attention during inpatient rehabilitation if institutionalization is to be avoided. The study population included 7219 patients with moderate-severe TBI in the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems (TBIMS) National Database enrolled from 2002–2012 who had not been institutionalized prior to injury. Based on institutionalization predictors in other populations, we hypothesized that among people who had lived at a private residence prior to injury, greater dependence in locomotion, bed-chair-wheelchair transfers, bladder and bowel continence, feeding, and comprehension at admission to inpatient rehabilitation programs would predict institutionalization at discharge. Logistic regression was used, with adjustment for demographic factors, proxy measures for TBI severity, and acute-care length-of-stay. C-statistic and predictiveness curves validated a five-variable model. Higher levels of independence in bladder management (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.88; 95% CI 0.83, 0.93), bed-chair-wheelchair transfers (OR, 0.81 [95% CI, 0.83–0.93]), and comprehension (OR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.68, 0.89]) at admission were associated with lower risks of institutionalization on discharge. For every 10-year increment in age was associated with a 1.38 times higher risk for institutionalization (95% CI, 1.29, 1.48) and living alone was associated with a 2.34 times higher risk (95% CI, 1.86, 2.94). The c-statistic was 0.780. We conclude that this simple model can predict risk of institutionalization after inpatient rehabilitation for patients with TBI.

Key words: : adult brain injury, outcome measures, predictive modeling, rehabilitation, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant public health issue.1,2 Persons who sustain moderate or severe TBI often have permanent disability that adversely impacts employment, functional independence, social and emotional well-being, life quality, and life expectancy.3–6 The direct and indirect annual medical cost of TBI is estimated to be between $60 and $76 billion, with the majority of costs associated with moderate or severe injuries.7,8

Optimal post-acute care for persons with TBI often includes multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation (IR) to manage secondary medical conditions and increase functional independence.9,10 A primary benchmark of IR effectiveness is returning persons with TBI who were independent prior to their injury back to their homes and avoiding long-term nursing facility (NF) placement. Yet little is known about NF placement rates or prognostic factors that place persons who sustain TBI at risk for institutionalization. In U.S. and European older adults (non-TBI population), consistent and stable risk factors for NF placement include greater age, living alone, functional motor dependence in basic care activities, and cognitive impairment, including dementia and delirium.11–16 Within the TBI population, greater severity of injury has been associated with institutionalization.17,18 However, no studies have addressed the contribution of the modifiable functional predictors on institutionalization after rehabilitation of people with TBI.

A prediction model for NF placement following IR can identify persons at risk and modifiable factors amenable to intervention, assist initiation of early case management and family decision-making, and clarify payer expectations and risk for financial reserve utilization. Healthcare policy reform efforts—including exploration of cost containment strategies such as bundled payments for an episode of TBI care—have been hampered by lack of prognostic evidence. Such reform would benefit from prediction models that identify factors associated with NF placement.19

This secondary analysis of a prospective, multi-center TBI registry examines risk of institutionalization for persons who sustained moderate and severe TBI and received IR. The primary objectives are twofold. First, we seek to describe NF placement rates for persons living independently prior to their TBI. Second, we aim to identify risk factors for institutionalization among data consistently available at IR admission, with a particular emphasis on finding modifiable risk factors that could be addressed through rehabilitation therapies and case management. We hypothesized that among people who had lived at a private residence prior to injury, after adjustment for demographic factors, severity, and acute care length of stay (LOS), greater dependence in locomotion, bed-chair-wheelchair transfers, bladder and bowel continence, feeding, and comprehension at admission to inpatient rehabilitation programs would predict institutionalization at discharge.

Methods

Study population

We studied a cohort of patients with moderate to severe TBI ages 16 years or older who were enrolled in the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems (TBIMS) National Database.20 Patients were eligible for inclusion if their Glasgow Coma Scale score was less than 13 in the emergency department, if they experienced post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) for more than 24 h, if they lost consciousness for more than 30 min, and/or if there were trauma-related intracranial neuroimaging abnormalities.20,21 TBIMS history, inclusion criteria, procedures and enrollment rates have been published elsewhere.21 This database is representative of adults receiving inpatient rehabilitation for TBI in the U.S.,22,23 where patients are required to be able to participate in 3 h of therapy 5 d a week to be eligible for admission. Participant data from January 1, 2002, to June 28, 2012 were studied to identify factors that predicted institutionalization rates under the current Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services IR facility prospective payment system.24 Twenty IR centers across the U.S. enrolled participants in the TBIMS database during this time period. The Institutional Review Board of each TBIMS facility approved registry participation and informed consent was provided by either the participant with TBI or their legal proxy.

The primary criterion for selecting the sample was whether the patient was living in a “private residence” immediately prior to the injury. The TBIMS private residence classification includes persons living in a house, apartment, mobile home, foster home, condominium, dormitory, military barracks, boarding school, boarding home, rooming house, bunk-house, boys ranch, fraternity/sorority house, commune, or migrant farm workers camp.20

Measures

The primary outcome “institutionalization” was defined as a discharge residence of “nursing home,” “adult home,” and “subacute care,” and encompassed residential nursing homes, long-term acute care facilities, adult foster care, independent living centers, transitional living facilities, assisted living facilities, supported living facilities, group homes, subacute hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities. Participant data were excluded from analyses when discharge residence data either did not fit criteria for private residence or institutionalization (e.g., hotel/motel, homeless, and transfer to another rehabilitation hospital setting) or was missing. Participant data also were excluded if there were missing values for several of our pre-specified predictors.

To address the factors relevant to our hypothesis, participants' level of independence in feeding, bladder management, bowel management, bed-chair-wheelchair transfers, locomotion (walking/wheelchair use), and comprehension were rated within 72 h of admission on a 7-point scale using the FIM System®.25–27 Other pre-specified predictors included demographic factors, proxy measures for TBI severity, and acute-care length of stay (LOS). Age at injury, gender, race, and lived-alone status prior to injury were collected based on interview of the most reliable source (e.g., patient and/or family member) as soon as possible after admission. Command following at admission was dichotomously coded based on the participant's ability to follow simple motor commands accurately two consecutive times within a 24-h period. The presence of PTA was determined using one of several equivalent standardized assessments28–31 for which threshold scores or criteria for emergence were met on two consecutive occasions within a period of one to three calendar days. Acute-care LOS was computed using injury and admission dates. Factors identified for check analyses included: highest level of educational attainment, employment status prior to injury, living with parents immediately prior to injury, pre-injury limitations in physical function, geographic region, year of inpatient rehabilitation admission, cause of injury, and 11 cognitive or motor functional independence items. A limited number of interactions also were identified for check analyses—namely, race and age and comprehension score and time post-injury.

Data collection and analyses

Research data staff trained and certified on the TBIMS IR admission and discharge protocol abstracted data from acute care and IR medical records, administered tests, and collected sociodemographic and pre-injury information from the most reliable source. Standardized administration procedures, comprehensive quality control standards, and automated data checks for completion and accuracy were used to minimize bias, random error, and attrition.20

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for patient sociodemographic characteristics, injury etiology, and functional impairment at time of admission. Differences between univariate analyses of persons discharged to private residence versus institutional care were calculated using Fisher's exact test for dichotomous and multinomial variables, and t-tests for ordinal and interval variables. We tested standard statistical assumptions, including collinearity. Age at injury was re-coded by dividing by 10 to improve the interpretability of the coefficients. FIM System items were centered by subtracting 4.5 (the numeric value between a 4-minimal assistance and 5-supervision rating) from each score in order to increase the interpretability of the constant term.

Logistic regression modeling was used to assess the contribution of the hypothesized predictors, with adjustment for demographic factors, proxy measures for TBI severity, and acute-care length-of-stay. Odds ratios, confidence intervals and the statistical significance of these pre-specified factors were computed. To control for type I error associated with clustered data, we used a modified t-statistic based on 19 degrees of freedom32 since our 20 (center) clusters were too few for reliable use of cluster-adjusted robust standard errors. This led to a cluster-adjusted alpha of p<0.04. Model performance was evaluated using the c-statistic to estimate discrimination and to help protect against overfitting, predictiveness curves.33 Even with data sets of a moderate size, it is easy to overfit models by including variables that, though statistically significant, are a) not affecting the outcome of interest and b) are mostly fitting noise in the data. Non-significant pre-specified factors were removed from the model if they did not influence the significance and strength of the identified predictors and did not greatly diminish model performance.

Once the non-significant factors were removed, check analyses first examined whether the inclusion of additional factors either mediated or moderated the effects of pre-specified predictors or improved model performance. Preference was given to keeping pre-specified factors in the model unless an added factor both clearly outperformed a pre-specified factor and had a strong conceptual rationale for inclusion. Check analyses then evaluated whether a more parsimonious final model could be achieved by removing the least predictive factors without diminishing either the influence of other predictors or model performance.

Internal validation was conducted on the final model via the bootstrap method34 using 1000 replications.35 External validation will be discussed in a future article. All analyses were performed using Stata, version 12.1.

Results

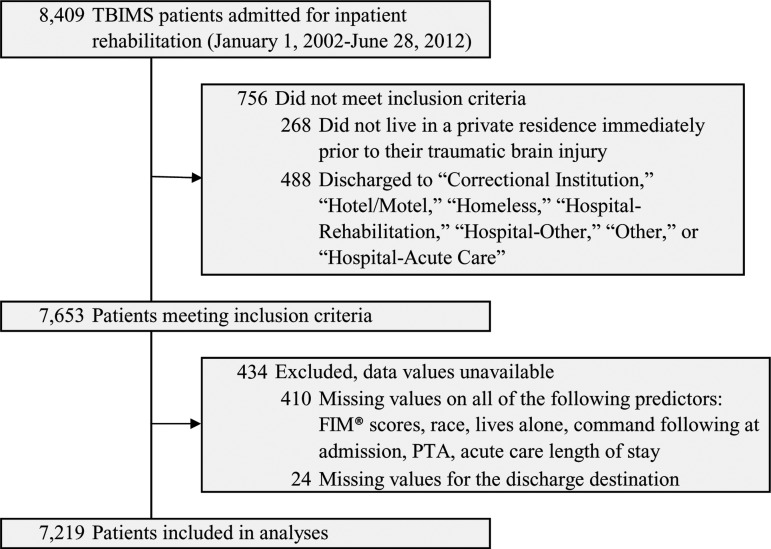

A total of 8409 participants were enrolled in the TBIMS National Database during our study period. Among these participants, 7653 met our inclusion criteria of living in a private residence immediately prior to injury and being discharged to either a private residence or an institution. Only 434 participants (5.7%) were excluded due to missing discharge residence data or missing data across predictors (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

TBIMS, Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems.

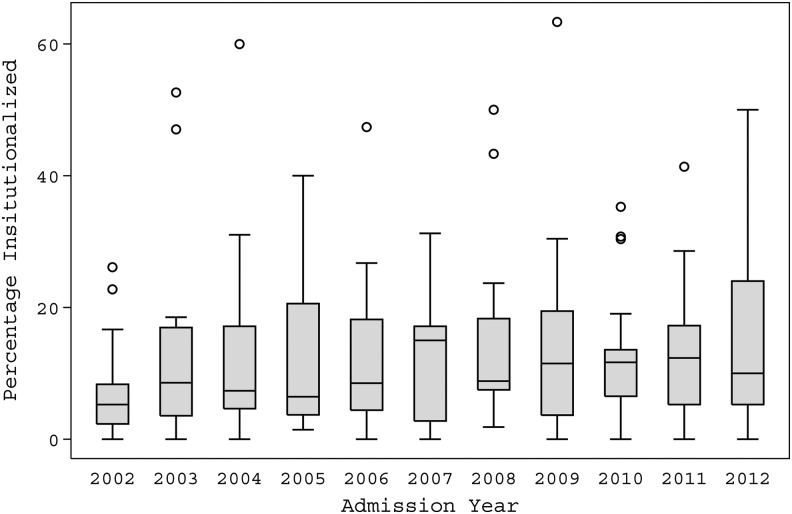

The mean rate of institutionalization at rehabilitation discharge across centers was 12.2% [95% CI, 11.4–12.9%%]. A lower rate of institutionalization (7.6%) was observed in 2002 than in the remainder of the study period and no other chronological differences or trends were observed (Fig. 2). There were seven occasions in which patients from a single center were discharged to institutions at rates greater than 40%; five of these seven were from a single center in which persons who were highly confused or remained in a disorder of consciousness were transferred to that center's subacute facility, which is not typical of most rehabilitation programs.

FIG. 2.

This graph depicts the range in the percentage of people discharged from the various Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems facilities each year. The horizontal line in the inside of each box is the median among the centers for that year; the upper and lower limits of each box are the 25th and 75th percentiles among the centers for that year; the length of the “whiskers” is equal to 1.5 times the interquartile range (75th percentile minus 25th percentile), while dots beyond the whiskers are called “outlying values.” The value for each center was weighted by the number of people admitted to the center that year.

The characteristics and pre-specified risk factors of our selected TBIMS cohort including 878 patients discharged to institution and 6341 discharged to private residence are presented in Table 1. The cohort was diverse with regard to age, sex, race, and pre-injury employment status. The majority of patients sustained injury as a result of vehicular accidents (53.1%) or falls (26.4%). The mean acute care LOS was 20 d. On admission to TBIMS rehabilitation center, the most patients were able to follow one-step commands (93.5%) but were confused (with 70.1% in PTA) and required assistance across all self-care and functional activities. Patients who were discharged to an institution were more likely to have the following demographic or rehabilitation admission characteristics: older age, lived alone prior to injury, longer acute care LOS, unable to follow one-step commands, in PTA, and more assistance required on self-care and functional activities.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Admission

| All participants (n=7219) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Institutionalized (878) | Non-institutionalized (6341) | p value | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 41.5 (19.6) | 53.5 (20.0) | 39.8 (18.9) | <0.00005 |

| Women, n (%) | 1950 (27.0) | 247 (28.1) | 1703 (26.9) | 0.425 |

| Race, n (%)* | 0.002 | |||

| White, n (%) | 5030 (69.7) | 646 (73.6) | 4384 (69.1) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 687 (9.5) | 53 (6.0) | 634 (10.0) | |

| Black, n (%) | 1236 (17.1) | 147 (16.7) | 1089 (17.2) | |

| Other, n (%) | 266 (3.7) | 32 (3.6) | 234 (3.7) | |

| Lives alone, n (%)* | 1245 (17.2) | 276 (31.4) | 969 (15.3) | <0.0005 |

| Employment* | <0.0005 | |||

| Competitively employed, n (%) | 4420 (61.3) | 411 (47.0) | 4009 (63.3) | |

| Student, n (%) | 476 (6.6) | 26 (3.0) | 450 (7.1) | |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 820 (11.4) | 90 (10.3) | 730 (11.5) | |

| Retired due to disability, n (%) | 374 (5.2) | 78 (8.9) | 296 (4.7) | |

| Retired due to age or other causes, n (%) | 861 (11.9) | 233 (26.6) | 628 (9.9) | |

| Taking care of the house of family, n (%) | 179 (2.5) | 22 (2.5) | 157 (2.5) | |

| Other, n (%) | 80 (1.1) | 15 (1.7) | 65 (1.0) | |

| Payer source* | <0.0005 | |||

| Medicare, n (%) | 1066 (14.8) | 251 (28.6) | 815 (12.9) | |

| Medicaid, n (%) | 1564 (21.7) | 159 (18.1) | 1405 (22.1) | |

| HMO, PPO, other private insurance, n (%) | 2975 (41.2) | 274 (31.2) | 2701 (42.6) | |

| Worker's compensation, n (%) | 371 (5.1) | 54 (6.2) | 317 (5.0) | |

| Private pay, n (%) | 249 (3.4) | 9 (1.0) | 240 (3.8) | |

| Auto insurance, n (%) | 381 (5.3) | 101 (11.5) | 280 (4.1) | |

| Other, n (%) | 562 (7.8) | 27 (3.1) | 535 (8.4) | |

| Cause of injury*,** | <0.0005 | |||

| Vehicular (e.g., MVA), n (%) | 3832 (53.1) | 321 (36.6) | 3511 (55.4) | |

| Violence (e.g., GSW, assault), n (%) | 746 (10.3) | 100 (11.4) | 646 (10.2) | |

| Falls, n (%) | 1,909 (26.4) | 351 (40.0) | 1558 (24.6) | |

| Pedestrian, n (%) | 463 (6.4) | 86 (9.8) | 377 (6.0) | |

| Other, n (%) | 257 (3.6) | 17 (1.9) | 240 (3.8) | |

| Acute-care LOS, mean (SD), d | 20 (15.8) | 24 (20.2) | 19.4 (15.0) | <0.00005 |

| Not following commands, n (%) | 470 (6.5) | 119 (13.6) | 351 (5.5) | <0.0005 |

| In PTA, n (%) | 5062 (70.1) | 715 (81.4) | 4347 (68.6) | <0.0005 |

| FIM System® | ||||

| Feeding, mean (SD) | 3.5 (2.1) | 2.6 (1.9) | 3.6 (2.1) | <0.00005 |

| Bowel management, mean (SD) | 3.3 (2.2) | 2.3 (1.9) | 3.4 (2.2) | <0.00005 |

| Bladder management, mean (SD) | 2.9 (2.2) | 1.9 (1.6) | 3.0 (2.2) | <0.00005 |

| Bed-chair-wheelchair transfers, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.5) | <0.00005 |

| Locomotion, mean (SD) | 2.2 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.6) | <0.00005 |

| Comprehension, mean (SD) | 3.6 (1.8) | 2.7 (1.6) | 3.7 (1.8) | <0.00005 |

This table displays information for all participants who met our inclusion criteria and had data for our outcome.

Within our study population, there were additional missing values for some of our predictors, including: 1 missing value for race, 3 missing values for “lives alone,” 9 missing values for employment, 51 missing values for rehabilitation payer source, and 12 missing values for cause of injury.

8 people were coded under more than 1 cause of injury.

SD, standard deviation; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred provider organization; MVA, motor vehicle accident; GSW, gunshot wound; LOS, length of stay; PTA, post-traumatic amnesia.

In our pre-specified logistic regression model, we found that increased age, living alone prior to injury, and longer acute care LOS increased the risk of institutionalization on rehabilitation discharge. Higher levels of independence with bladder management, bed-chair-wheelchair transfers, and comprehension decreased the risk of institutionalization on discharge. The c-statistic for the pre-specified model was 0.795. Removal of sex, race, in PTA, command following, bowel management, and locomotion as predictors did not change the significance of the remaining predictors or model performance. There was no significant collinearity among the variables in our pre-specified model.

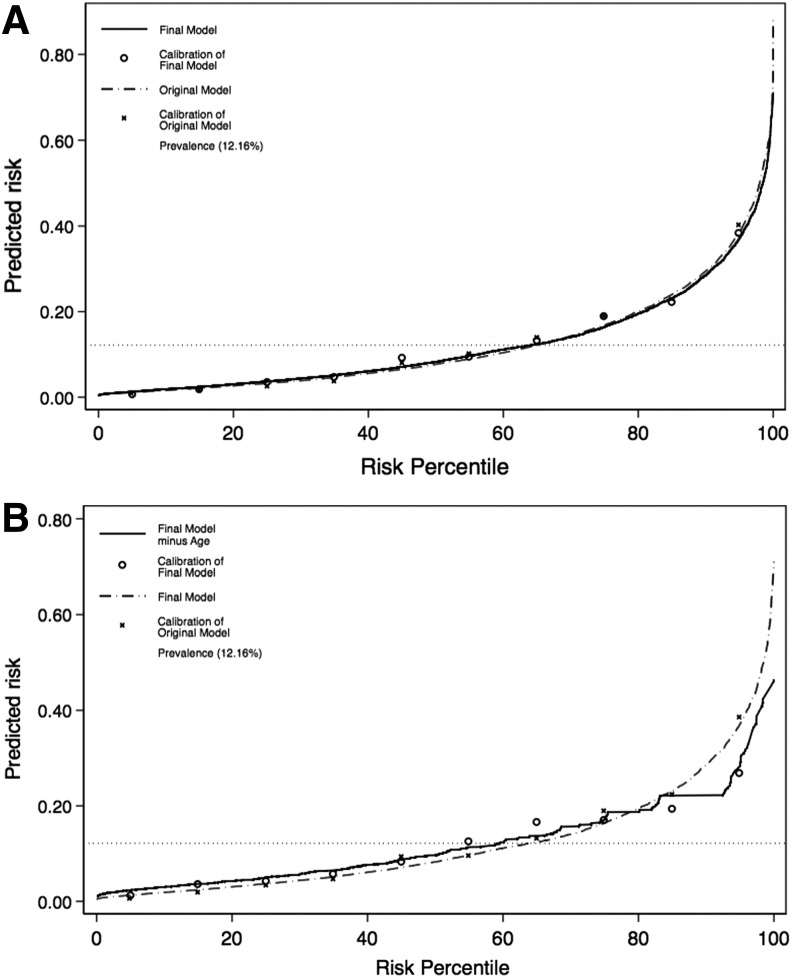

Check analyses focusing on FIM System items demonstrated that the other FIM System items were either not statistically significant or if significant, did not improve model performance (Fig. 3). Level of educational attainment, geographic region, pre-morbid limitations on physical function, cause of injury, employment status prior to injury, interaction between race and age, and interaction between FIM System comprehension scores and acute-care length-of-stay also did not improve model performance.

FIG. 3.

Predictiveness curves and their calibration points are demonstrated in these graphs, as well as the overall prevalence of institutionalization within the study population. In 3A, we see the original and final models. In 3B, we see the final model and the final model without age.

The final model included five variables: age, living alone, independence with bladder management, independence with bed-chair-wheelchair transfers, and independence with comprehension (Table 2). For every 10-year increment in age was associated with a 1.38 times higher risk for institutionalization (95% CI, 1.29, 1.48) and living alone was associated with a 2.34 times higher risk (95% CI, 1.86, 2.94). Higher levels of independence in bladder management (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.88; 95% CI 0.83, 0.93), bed-chair-wheelchair transfers (OR, 0.81 [95% CI, 0.83–0.93]), and comprehension (OR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.68, 0.89]) were associated with lower risks of institutionalization on discharge. The c-statistic for our final model was 0.780. Predictiveness curves demonstrated a minimal difference between our initial and final model (Fig. 3A), but a significant difference between our final model and a model without one of our key variables (Fig. 3B).

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for Institutionalization at Discharge Among TBIMS Cohort: Final Model

| Final Model | Bootstrap results (1000 replications) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | Bias | Bias-corrected 95% CI for OR | |

| Age (10-year increments) | 1.38 | 1.29–1.48 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 1.30–1.49 |

| Lives alone prior to injury | |||||

| No | 1 [Referent] | ||||

| Yes | 2.34 | 1.86–2.94 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 1.81–2.82 |

| FIM System® at admission | |||||

| Bladder management | 0.88 | 0.83–0.93 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.83–0.93 |

| Bed-chair-wheelchair transfers | 0.81 | 0.73–0.91 | 0.001 | −0.006 | 0.73–0.90 |

| Comprehension | 0.78 | 0.68–0.89 | <0.001 | −0.001 | 0.68–0.88 |

The c-statistic for our final model is 0.780.

TBIMS, Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Internal validation using the bootstrap method found that all variables in the final model still met our inclusion criteria and that the confidence intervals for the bootstrapped coefficients were narrow (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study shows that individuals who are admitted to IR after moderate-severe TBI are more likely to be discharged to an institutional setting if they are older, lived alone prior to their injury, and had lower levels of independence in transfers, verbal comprehension, and bladder management upon admission to IR. These results indicate that clinical features likely to influence discharge disposition span demographic, sociobiological, and functional performance realms. Our model is consistent with factors shown to be associated with admissions to nursing homes in the U.S. elderly population. Increasing age, living alone, cognitive impairment particularly dementia, psychiatric diagnoses, and limited functional performance (activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living) have all been shown to strongly predict the need for skilled care in the United States and Europe.11–15,36,37

These findings uniquely inform clinical decision making as they are derived from the largest non-proprietary longitudinal data set concerning individuals with TBI that is representative of patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for TBI in the United States.22,23 While age and pre-injury living status are important to consider when establishing a plan of care on admission to IR, skills for independence improve with recovery, making prediction of outcome for any individual challenging and the discharge planning process dynamic. Focusing resources and clinical programming on potentially modifiable functional limitations may have the most influence on discharge location.

While 88% of patients in this study were discharged to a private residence, patients did not necessarily return to the same pre-injury private residence. A change in residence from pre-injury is common when patients are hospitalized for rehabilitation after moderate-severe TBI, with 35% discharged to a location different from pre-injury.14,17 Further, the 12% institutionalized in our study include both short- and long-term placements. Previous research suggests that more than 50% of institutionalized patients returned to their previous living setting in subsequent years,17 which highlights that recovery after TBI does not stop when a patient leaves IR but continues for years after injury.

The characteristics of individuals referred to rehabilitation after TBI are determined by an admission process that is unique to the acute care institution and rehabilitation hospital at each center. These decisions are informed by multiple considerations beyond injury severity, comorbidities, impairment level, and functional status. The presence of a primary payer source, family support structure, and plausible discharge plan also are closely considered. For individuals hospitalized for acute care after moderate-severe TBI, injury severity has been shown to be a primary determinant of whether or not they are discharged home.38 However, sociobiologic (age, sex) and socioeconomic (payment source, race/ethnicity) factors appear to have more influence on the decision about acute hospital discharge to IR or skilled care.38

Our findings have important healthcare policy implications. Medicaid policies for determining eligibility for skilled nursing facility (SNF) level of care consider financial and medical eligibility criteria. There is little understanding of this process, which is highly variable across states. Establishing minimum dataset requirements across IR and SNF facilities for post-acute care admission is needed to better track and compare rehabilitation service delivery and associated outcomes to determine clinical characteristics that identify persons who may best benefit from IR. Comparative intervention research across settings may help identify qualitative and quantitative differences in care that may or may not be related to setting.

Our model provides facilities, such as accountable care organizations, with a simple tool that can be used to identify persons at risk for short-term, post-acute rehabilitation NF placement and help them anticipate the need for either longer duration of IR services or NF discharge planning. Given the consistency of NF placement risk factors across diseases, developing and evaluating interventions that focus on these risk factors to reduce short- and long-term institutionalization in persons with TBI is warranted. In addition, due to the large number of patients that are admitted to NF's and their associated costs, further research that evaluates factors influencing changes in institutionalization at six- and 12-months post-injury is warranted.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. We did not evaluate early measures of TBI severity and neurological impairment (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale) because these data are often not available in the acute medical record. Medical acuity variables were not recorded in the TBIMS dataset for these cases, which also may contribute to unexplained variance in predicting institutionalization. However, acute LOS as a gross marker of medical acuity did not contribute to the final model. Age may incorporate aspects of slower and/or lower rates of natural recovery, pre-existing normal decline in functioning, as well as an increased risk for pre-existing chronic medical conditions (e.g., coronary artery disease) that may alone or in combination influence risk of placement. Socioeconomic factors, such as household income and family support, may also influence discharge placements but these data are often not provided by research participants. Caregiver age of 65 or older and perceived burden are consistent and stable predictors of institutionalization in other populations39–41 but is not currently collected in the TBIMS dataset. Future research on predicting institutionalization following TBI would benefit from examining perceived caregiver burden and the interaction between caregiver and patient factors.

Conclusion

Using a large national dataset, we developed a model that predicted risk of institutionalization after inpatient rehabilitation for TBI based on data available at admission to post-acute care inpatient rehabilitation programs. We found that most patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation facilities are discharged home. The most significant risk factors for institutionalization were demographic or functional. This model may be useful in guiding a patient's care plan, but cannot replace individual clinical assessments. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether or not improving patients' functional status with regard to bladder management, bed-chair-wheelchair transfers, and comprehension in the acute care or rehabilitation setting can lead to lower rates of institutionalization. Such studies could also elucidate the relative impact of each of these functional domains.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, Office of Special Education Services, Department of Education to Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital (H133A120085), Shepherd Center-Georgia Model Brain Injury System (H133A110006), Mayo Clinic (H133-A120026), MossRehab (H133A120037), Virginia Commonwealth University (H133A120031), and Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (H133A080045). However, the contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education and endorsement by the federal government should not be assumed. This work also was supported in part by a grant from the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital/Harvard Medical School.

The data for the external validation study was obtained and used with permission from the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, a division of the University at Buffalo Foundation Activities, Inc. The service marks and trademarks associated with the FIM System instrument are all owned by Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. We would like to thank Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, WA) statistician Gary Longton for supplying us with the basic Stata code for the predictiveness curves and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital research associate Matthew Doiron for sharing his spreadsheet expertise.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Faul M., Xu L., Wald M.M., and Coronado V.G. (2010). Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths 2002–2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronado V.G., McGuire L.C., Sarmiento K., Bell J., Lionbarger M.R., Jones C.D., Gellar AI, Khoury N, and Xu L. (2012). Trends in traumatic brain injury in the U.S. and the public health response: 1995–2009. J. Safety Res. 43, 299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thurman D.J., Alverson C., Dunn K.A., Guerrero J., and Sniezek J.E. (1999). Traumatic brain injury in the United States: A public health perspective. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 14, 602–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaloshnja E., Miller T., Langlois J.A., and Selassie A.W. (2008). Prevalence of long-term disability from traumatic brain injury in the civilian population of the United States, 2005. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 23, 394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selassie A.W., Zaloshnja E., Langolis J.A., Miller T., Jones P., and Steiner C.Incidence of long-term disability following traumatic brain injury hospitalization, United States, 2003. (2008). J Head Trauma Rehabil. 23, 123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ventura T., Harrison-Felix C., Carlson N., Diguiseppi C., Gabella B., Brown A., Devivo M., and Whiteneck G. (2010). Mortality after discharge from acute care hospitalization with traumatic brain injury: a population-based study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 91, 20–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein E., Corso P.S., and Miller T.R. (2006). The incidence and economic burden of injuries in the United States. Oxford University Press: Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockhill C.M., Jaffe K., Zhou C., Fan M.Y., Katon W., and Fann J.R. (2012). Health care costs associated with traumatic brain injury and psychiatric illness in adults. J. Neurotrauma 29, 1038–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIH Consensus conference. (1999). Rehabilitation of persons with traumatic brain injury. JAMA 282, 974–983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon W.A., Zafonte R., Cicerone K., Cantor J., Brown M., Lombard L., Goldsmith R., and Chandna T. (2006). Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: state of the science. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 85, 343–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bharucha A J., Pandav R., Shen C., Dodge H.H., and Ganguli M. (2004). Predictors of nursing facility admission: a 12-year epidemiological study in the United States. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 52, 434–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozzini L., Cornali C., Chilovi B.V., Ghianda D., Padovani A., and Trabucchi M. (2006). Predictors of institutionalization in demented patients discharged from a rehabilitation unit. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 7, 345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaugler J.E., Duval S., Anderson K.A., and Kane R.L. (2007). Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 7, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai Q., Salmon J.W., and Rodgers M.E. (2009). Factors associated with long-stay nursing home admissions among the U.S. elderly population: comparison of logistic regression and the Cox proportional hazards model with policy implications for social work. Soc. Work Health Care 48, 154–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luppa M., Luck T., Matschinger H., König H.H., and Riedel-Heller S.G. (2010). Predictors of nursing home admission of individuals without a dementia diagnosis before admission - results from the Leipzig Longitudinal Study of the Aged (LEILA 75+). BMC Health Serv. Res. 10, 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witlox J., Eurelings L.S., de Jonghe J.F., Kalisvaart K.J., Eikelenboom P., and van Gool W.A. (2010). Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia. JAMA 304, 443–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Penna S., Novack T.A., Carlson N., Grote M., Corrigan J.D., and Hart T. (2010). Residence following traumatic brain injury: a longitudinal study. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 25, 52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dikmen S., Ross T., Machamer J., and Temkin N. (1995) One year psychosocial outcome in head injury. J. Internal Neuropsychol. Soc. 1, 67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2013). Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. MedPAC: Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Data and Statistical Center. (2009). Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database Syllabus. Available at: https://www.tbindsc.org/Syllabus.aspx Acessed October15, 2014

- 21.Dijkers M.P., Harrison-Felix C., and Marwitz J.H. (2010). The traumatic brain injury model systems: history and contributions to clinical service and research. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 25, 81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corrigan J.D., Cuthbert J.P., Whiteneck G.G., Dijkers M.P., Coronado V., Heinemann A.W., Harrison-Felix C., and Graham J.E. (2012). Representativeness of the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 27, 391–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuthbert J.P., Corrigan J.D., Whiteneck G.G., Harrison-Felix C., Graham J.E., Bell J.M., and Coronado V.G. (2012). Extension of the representativeness of the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database: 2001 to 2010. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 27, E15–E27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2013). Rehabilitation Facilities (Inpatient) Payment System. MedPAC: Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinemann A.W., Linacre J.M., Wright B.D., Hamilton B.B., and Granger C. (1993). Relationships between impairment and physical disability as measured by the Functional Independence Measure. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 74, 566–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linacre J.M., Heinemann A.W., Wright B.D., Granger C.V., and Hamilton B.B. (1994). The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 75, 127–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ottenbacher K.J., Hsu Y., Granger C.V., and Fiedler R.C. (1996). The reliability of the Functional Independence Measure: a quantitative review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 77, 1226–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin H.S., O'Donnell V.M., and Grossman R.G. (1979). The Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test: A practical scale to assess cognition after head injury. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 167, 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bode R.K., Heinemann A.W., and Semik P. (2000). Measurement properties of the Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test (GOAT) and improvement patterns during inpatient rehabilitation. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 15, 637–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson W.T., Novack T.A., and Dowler R.N. (1998). Effective serial measurement of cognitive orientation in rehabilitation: the Orientation Log. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 79, 718–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novack T.A., Dowler R.N., Bush B.A., Glen T., and Schneider J.J. (2000). Validity of the Orientation Log, relative to the Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 15, 957–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cameron A.C. and Miller D.L.Robust inference with clustered data. (2011). Handbook of Empirical Economics. CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pepe M.S., Feng Z., Huang Y., Longton G., Prentice R., Thompson I.M., and Zheng Y. (2007). Integrating the predictiveness of a marker with its performance as a classifier. Am. J. Epidemiol. 167, 362–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrell F.E., Jr. (2001). Regression Modeling Strategies. Springer: New York [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunkemeier G.L. (2004). Bootstrap resampling methods: something for nothing? Ann. Thorac. Surg. 77, 1142–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodwin J.S., Howrey B., Zhang D.D., and Kuo Y.F. (2011). Risk of continued institutionalization after hospitalization in older adults. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 66, 1321–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlegel D.J., Tanne D., Demchuk A.M., Levine S.R., and Kasner S.E.; Multicenter rt-PA Stroke Survey Group. (2004). Prediction of hospital disposition after thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Arch. Neurol. 61, 1061–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cuthbert J.P., Corrigan J.D., Harrison-Felix C., Coronado V., Dijkers M.P., Heinemann A.W., and Whiteneck G.G. (2011). Factors that predict acute hospitalization discharge disposition for adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 92, 721–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Black T.M., Soltis T., and Bartlett C. (1999). Using the Functional Independence Measure instrument to predict stroke rehabilitation outcomes. Rehabil. Nurs. 24, 109–114, 121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buhr G.T., Kuchibhatla M., and Clipp E.C. (2006). Caregivers' reasons for nursing home placement: clues for improving discussions with families prior to the transition. Gerontologist 46, 52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yaffe K., Fox P., Newcomer R., Sands L., Lindquist K., Dane K., and Covinsky K.E. (2002). Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA 287, 2090–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]