Abstract

Introduction

Recurrent or persistent low back pain is common after back surgery but is typically not well controlled. Previous randomised controlled trials on non-acute pain after back surgery were flawed. In this article, the design and protocol of a randomised controlled trial to treat pain and improve function after back surgery are described.

Methods and analysis

This study is a pilot randomised, active-controlled, assessor-blinded trial. Patients with recurring or persistent low back pain after back surgery, defined as a visual analogue scale value of ≥50 mm, with or without leg pain, will be randomly assigned to an electroacupuncture-plus-usual-care group or to a usual-care-only group. Patients assigned to both groups will have usual care management, including physical therapy and patient education, twice a week during a 4-week treatment period that would begin at randomisation. Patients assigned to the electroacupuncture-plus-usual-care group will also have electroacupuncture twice a week during the 4-week treatment period. The primary outcome will be measured with the 100 mm pain visual analogue scale of low back pain by a blinded evaluator. Secondary outcomes will be measured with the EuroQol 5-Dimension and the Oswestry Disability Index. The primary and secondary outcomes will be measured at 4 and 8 weeks after treatment.

Ethics and dissemination

Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Pusan National University Korean Hospital in September 2013 (IRB approval number 2013012). The study findings will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at national and international conferences.

Trial registration number

This trial was registered with the US National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Registry: NCT01966250.

Keywords: COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE, NEUROSURGERY, PAIN MANAGEMENT, REHABILITATION MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This trial is designed to be a feasible, comparative effectiveness trial design that is similar to common clinical situations.

Individualised acupuncture points according to patients’ symptoms during the delivery of acupuncture treatment reflect the real clinical practice of acupuncture.

We expect that this pilot study will provide the clinical basis and information that is required to assess the feasibility of a future large-scale trial.

Blinding the practitioner will not be done in this trial because it is impossible to blind acupuncturists.

The size of the study sample limits the power of the observations.

Introduction

Billions of dollars have been spent worldwide in the past few years on lumbar spine surgery to treat chronic low back pain (LBP), and thousands of studies have been devoted to the subject.1 Lumbar spine surgery is becoming more common, and there is a wide range of surgical procedures.2 Complications can be acute or can occur later after surgery, and they can lead to worsening or to lack of resolution of the original symptoms.3 Approximately, 40% of patients who undergo lumbar spine surgery continue to report significant pain after the surgery.4 Pain management is a very important element of patient care because pain is the most common complication of back surgery.5 6 Various opioid analgesics, including morphine, hydromorphine and meperidine, have been used for postoperative pain management.7 However, opioids are frequently observed to have unwanted side effects, such as nausea and vomiting.8 Therefore, there is a need for safe and effective pain management after back surgery.

Numerous studies have shown that acupuncture is generally safe9 10 and cost-effective11 compared with routine care.12 13 Electroacupuncture (EA) is also commonly used for pain management.14–16 The primary goal of EA treatment after back surgery is pain reduction. There has been a systematic review of current evidence concerning the effectiveness of acupuncture for relieving acute postoperative pain after back surgery.17 However, there have been only a few clinical trials18 19 that evaluated the effectiveness of EA for non-acute postoperative pain after back surgery, and the quality of these studies is too low to draw any meaningful conclusions.

In Korea, because of cultural influence, many potential study participants who are between 19 and 70 years old have already had experience with acupuncture. This makes it difficult to implement participant blinding and practitioner blinding given the nature of acupuncture.20 21

We therefore propose to conduct a pilot feasibility study to establish an appropriate sample size before conducting a confirmative, pragmatic, comparative randomised controlled trial (RCT) to demonstrate the effectiveness of EA in combination with usual care (UC) compared with UC alone for controlling non-acute pain and function at ≥3 weeks22 after the back surgery. The study will adhere to STRICTA23 and CONSORT24 guidelines.

Aims

The primary purpose of this study is to explore whether EA in combination with UC can provide benefits to patients with non-acute pain and dysfunction after back surgery. It is also a pilot feasibility study that is designed to estimate the appropriate sample size for a future confirmative, pragmatic, comparative RCT that would verify the effectiveness of EA in combination with UC (drug treatment and physical therapy) compared with UC alone in relieving non-acute pain and dysfunction after back surgery. The dependent variables are pain relief, enhancing disease-related functional status and improved quality of life. We also aim to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis and a qualitative study with the pilot data, but these results will be reported separately.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This study is a randomised, active-controlled, assessor-blinded pilot trial with two parallel arms. The trial will be conducted in the Pusan National University Korean Medicine Hospital (PNUKH) in Yangsan, Korea. This study protocol is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01966250, 11-Oct-2013).

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Patients whose LBP recurred or persisted after back surgery, with or without leg pain.

Patients whose pain persisted for at least 3 weeks (non-acute) after back surgery and who require intermittent medical treatment, such as medication, injection or physical therapy.

Patients with LBP, defined as a visual analogue scale (VAS) value of ≥50 mm.

Patients who are between 19 and 70 years of age.

Patients who agreed to participate voluntarily in this study and signed written informed consent forms.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who have been diagnosed with a serious disease that can cause LBP, including cancer, vertebral fracture, spinal infection, inflammatory spondylitis and cauda equina compression.

Patients with a progressive neurological deficit or with severe neurological symptoms.

Patients whose pain is not caused by spinal or soft tissue diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

Patients with a chronic disease that could influence the treatment effects or results (eg, severe cardiovascular disease, diabetic neuropathy, dementia or epilepsy).

Patients for whom EA might be inappropriate or unsafe (eg, because of haemorrhagic disease, clotting disorders, a history of having received anticoagulant therapy within the preceding 3 weeks, severe diabetes with a risk of infection or severe cardiovascular disease).

Patients who are currently pregnant or planning to become pregnant.

Patients with psychiatric diseases.

Patients who are participating in another clinical trial.

Patients who are unable to sign a written informed consent form.

Patients who are judged to be inappropriate for the clinical study by the researchers, such as those who are unable to read and write Korean.

Recruitment

Patients will be recruited by advertisements on hospital websites, bulletin boards and in local newspapers. If hospital patients are interested in participating, they will be asked to answer screening questions to determine their eligibility. If they are eligible, they will be guided through the written informed consent process. After written consent is obtained, a study researcher will administer the baseline questionnaire. Patients who have been determined on the basis of the selection and exclusion criteria to be suitable for the clinical trial will be assigned randomly on a second visit to either the UC-plus-EA group or the UC-alone group, with a 1:1 ratio. After randomisation, a clinical research coordinator (CRC) will schedule the treatment procedure. The first participant was enrolled in 29 October 2013.

Randomisation

Before the first treatment session, a statistical expert will assign patients to one of the two groups by use of a central telephone randomisation process according to a computer-generated randomisation sequence that uses SPSS V.19.0 (IBM Co, Armonk, New York, USA).Randomisation will be conducted by a trial coordinator who will have no contact with the patients. The CRC will obtain the codes for the trial (A or B) from a central telephone and inform the practitioner. The practitioner will then use these codes to assign patients to one of the two groups and to deliver the appropriate treatment.

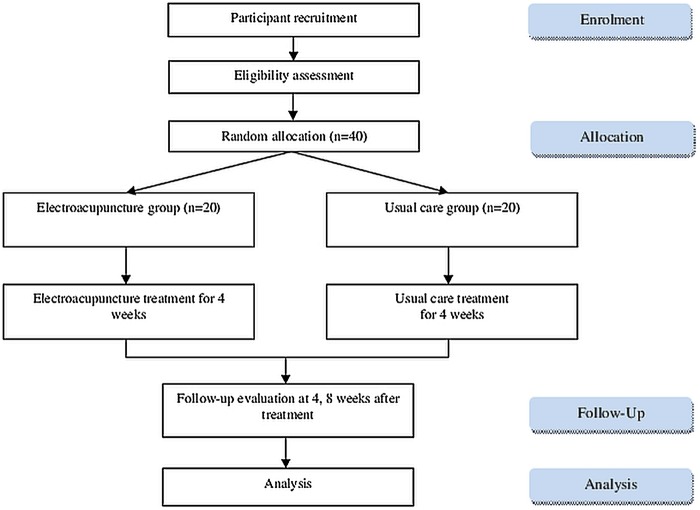

The National Clinical Research Centre at the PNUKH will store the random number. The allocation sequence will be concealed from the researcher who is responsible for enrolling, treating or assessing patients (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the steps in participant recruitment, treatment and analysis.

Blinding

It is not possible to blind patients or practitioners in our trial because of the nature of EA and because there is no placebo. However, there is protection from detection bias because treatment and assessment will be conducted independently, and the practitioners will not be involved in outcome assessment.25 The assessors will always perform outcome assessments in a separate room and will always be blinded to treatment assignment. Unblinding of assessors should be performed only when exceptional circumstances occur as knowledge of the actual treatment is absolutely essential for further management of the patient (eg, serious adverse event).

Education of practitioners for standardisation

The licensed Korean medicine doctors (KMDs) who will be involved in this trial as practitioners or assessors have all been certified by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, have at least 3 years of clinical experience, and will have taken a course to ensure that they adhere strictly to the study protocol and are familiar with administering the study treatments. All participating KMDs underwent intensive and customised training for a full understanding of the EA procedure, including such details as acupuncture points, depth and manipulation. All study protocols and details, including the recording method for the case report form and outcome assessment methods, were additionally standardised among the assessors by means of 10 h of training on the standard operating procedure.

Interventions

Patients who are randomised to both arms will have UC management during the 4-week treatment period, which begins at randomisation. It is assumed in this study that UC includes drug therapy, physiotherapy or an educational programme about LBP.22 Conventional medicinal drug treatment or therapies (eg, pain medication, injection or physiotherapy, but not surgical treatment) that are related to treating LBP after back surgery will be allowed, and they will be monitored. Physiotherapy and an educational programme about back pain will be performed twice a week for 4 weeks by licensed KMDs. Interferential current therapy (ICT, OG Giken Co, Okayama, Japan) will last 15 min, and therapy with a hot (or ice) pack will last 10 min. The education programme will be conducted through the brochure, including the physiology, pathology and epidemiology of pain after back surgery. Additionally, KMDs will present suitable postures and exercises for LBP in 15 min face-to-face education sessions.

Patients who are randomised to the UC-plus-EA group will have EA treatment in addition to the UC. In the UC-plus-EA group, the acupuncture point prescriptions used will be personalised to each patient and at the discretion of the practitioner. Differentiating the acupuncture point is an important part of traditional Korean medical theory and of creating the actual clinical situation, so it was used to select acupuncture points according to patients’ symptoms. EA treatment procedures were designed to reflect the feasibility afforded by the actual clinical setting by a consensus of five experts on acupuncture and the spine. EA treatment will be performed by licensed KMDs using disposable stainless steel needles that are 0.25 mm in diameter and 0.40 mm in length (Dongbang Acupuncture Inc, Seongnam, Korea). Electric stimulation will be applied with an ES-160 electronic stimulator (ITO co. LTD, Japan) twice a week for 4 weeks. Stimulation will be applied with biphasic waveform current, which is a compressional wave that combines an interrupted wave and a continuous wave, in triangular form, at a frequency of 50 Hz.26 Acupuncture points will include Jia-ji (Ex-B2, L3-L5; bilateral) as required points and other reasonable points can be chosen by the practitioner as accessory points. Between 6 and 15 access points will be used by the physicians according to the individual clinical features of each patient. Electric stimulation will be given through alligator clips, connected to Jia-ji (Ex-B2, L3/L5; bilateral). Each EA session will last 15 min. Patients in both groups will have had a total of eight treatment sessions during 4 weeks.

The rationale of the lack of a placebo/sham intervention group

The primary purpose of this study is to explore whether EA combined with UC can provide benefits to patients with non-acute pain after back surgery. Currently, sham or placebo EA is used to assess the efficacy of the specific component of the EA while reducing any possible influence from clinical contexts and other treatment-related processes.27 28 However, with the purpose of pragmatic, comparative effectiveness RCT of future trial, we decided not to employ a placebo/sham EA as a control group.

Outcome assessment

At the initial screening visit, a CRC will ask patients to complete a questionnaire regarding their sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, height, weight and vital signs. A CRC or KMD with more than 2 years of clinical experience will record the outcomes in a separate room according to the standardised operating procedure without knowing to which group the patients have been assigned. Before the start of treatment at each visit, patients will be assessed to record the outcomes of the previous treatments. Any disease history or adverse events will be recorded and will be used to decide if a participant should continue in the trial. Follow-up assessments will be performed at 4 and 8 weeks after the 4-week treatment period (table 1 and figure 1).

Table 1.

Schedule for data collection and outcome measurement

| Baseline | Active treatment |

Follow-up |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Week 0 | 1st week |

2nd week |

3rd week |

4th week |

8th week* | 12th week* | ||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | √ | ||||||||||

| Back pain history | √ | ||||||||||

| Physical examination | √ | ||||||||||

| Visual analogue scale for back pain | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Oswestry Disability Index | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| EuroQol 5-Dimensions | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Adverse events | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

*8, 12-weeks indicates 4 and 8 weeks, respectively, after 4 weeks of electroacupuncture treatment.

Primary outcome measurements

Back pain intensity will be assessed using the 100 mm pain VAS, on which 0 indicates the absence of pain and 100 indicates unbearable pain.29 30 The VAS was selected as a primary outcome measurement of the clinical severity of patients’ pain after back surgery. Using the 100 mm pain VAS, the participant will be asked to check his or her degree of back pain for the previous 3 days. Back pain will be measured at baseline (assessment 1), prior to each of the eight treatment sessions (assessments 2 through 9), and during the two follow-up visits (assessments 10 and 11). The primary end point is assessment 10, which marks the end of the eight active treatment sessions.

Secondary outcome measurements

The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) is one of two secondary outcome measurements that will be used. The ODI assesses back pain-related disability.31 It contains 10 questions about daily life, including measures of pain intensity, personal care, lifting, walking, sitting, standing, sleeping, social life and travelling. Each question is rated on a scale of 0–5, with a higher score indicating a more severe pain-related disability. The validated Korean version of the ODI32 will be administered before treatment on the first, fourth and eighth treatment sessions (assessments 2, 5 and 9) and during each of the two follow-up sessions (assessments 10 and 11).

Responder, defined as a participant with 50% or more pain relief using a 100 mm VAS for pain intensity, versus non-responder (under 50% pain relief) will be assessed at eighth treatment session (assessment 9) and the two follow-up sessions (assessments 10 and 11). The EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) will also be used as a secondary outcome measurement. The quality of life of patients with back pain will be assessed using the validated Korean version of the EQ-5D.33 34 The EQ-5D includes generic questions about quality of life as it relates to personal health. The EQ-5D consists of five dimensions that pertain to mobility (mobility), self-care (self-care), daily activities (usual activities), pain and discomfort (pain), and anxiety and depression (anxiety/depression). Each dimension is scored on a scale of 1–3, with a lower score indicating a better state of participant health. The EQ-5D will be administered before treatment on the first, fourth and eighth treatment sessions (assessments 2, 5 and 9) and during each of the two follow-up sessions (assessments 10 and 11).

Data management

Data and safety monitoring will be conducted periodically during the study and at least once a year thereafter. Only specific research assistants will have access to the final trial data set. The research assistants will consist of two independent researchers (one in biomedical statistics, one in clinical expert of Korean medicine) who will not be involved in the trial. Monitors will oversee study protocol compliance, informed consent documents, overall progress of the trial, participant recruitment, data quality and timeliness, performance of the intervention and all fields and processes of the trial. If any important protocol modifications exist, we will resubmit amended protocol to Institutional Review Board (IRB). Important protocol modifications will be announced to relevant parties (eg, investigators, IRB, trial participants, trial registries and sponsor). Audit will be carried out by the Korean Food & Drug Administration that adheres to its rule. Interim analysis will not be applied because we expect this small pilot trial to be a minimal risk of harm to be associated with EA and UC. All study-related information will be stored securely at the study site. All participant information will be stored for 10 years in locked file cabinets in areas with limited access.

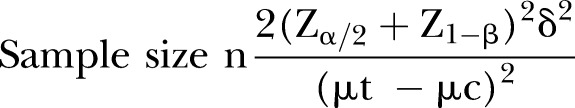

Sample size

Although our study is a pilot trial, we attempted to approximate a sample size that would be suitable for a future, large, pragmatic, multicentred, comparative effectiveness RCT. We also attempted to estimate more exactly the power of a future trial. The sample size for the future clinical study was estimated by comparing the mean difference in the VAS for LBP between the experimental and control groups in the pilot study. As there was no same trial with our design of RCT, we estimated the sample size on the basis of other similar previous study.35–37 The mean difference in the pain VAS for LBP between the experimental and control groups was 20 mm suggested as clinically important change.38 39 The SD between the two groups was estimated to be 19, based on other published results.18 19 40 When a two-tailed test with a test power of 80% and a significance level of 5% (α error) was applied to the following formula, the number of participants required for each group was found to be 16. Considering a dropout rate of 20% and a 1:1 allocation ratio, the total sample size was calculated to be 20. On the other hands, in previous pilot trials which were performed without calculating the number of sample size to enforce the number of samples of 20.28 35–37 41 42

|

n=the number of participants required in each group

μt–μc=20

δ=19

Zα/2=Z0.05/2=1.96

Z1–β=Z0.8=0.84

Statistical methods and analysis

The statistical analysis will be performed according to the principle of intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and perprotocol (PP) analysis. In the case of ITT analysis, we will apply the last-observation-carried-forward rule for missing data. In parallel, PP analysis will be conducted without patients who dropped out of the clinical trials for any reason. Additionally, the subgroups of patients with pain after back surgery will be evaluated and analysed (subgroup analysis) for exploring potential future research. Subgroup analysis will be conducted according to the type of surgery (ie, fusion, decompression or discectomy), surgically involved spine(s) (which level(s) was/were and how many levels were involved) and postoperative period (subacute: 3 weeks or more to 3 months vs chronic: more than 3 months) for exploring the feasibility of future trial. The significance of the differences in the various data in each group will be analysed with a paired t test, and the significance of the differences between groups will be analysed with an independent t test. An analysis of covariance will be used to analyse and adjust baseline characteristics if there are statistically significant differences and there is a possibility of covariance of baseline characteristics. Non-parametric statistical tests (a Wilcoxon signed-rank test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test) will be used if the data are not normally distributed. A χ2 test or a Fisher's exact test will be performed to analyse categorical data, such as responses/responders that are recorded and described as frequencies (%). All statistical analyses will be conducted with SPSS statistical software (IBM Co, Armonk, New York, USA) for Windows, V.19.0, by a statistician. The significance level will be set at 5%. Sample size estimation was conducted by the free program of G*Power V.3.1.7 (Franz Faul, Uniesität Kiel, Germany).

Safety

All possible adverse events that could affect patients will be monitored and reported for every trial by the participating researchers. Every expected or unexpected adverse event related to this study will be recorded and monitored until it is resolved. And those who suffer harm from trial participation can be given medical treatment for compensation. The research team will report any differences in the safety of the experimental and control groups.

Ethics and dissemination

In conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki,43 all participants will be recruited to participate voluntarily, and they will sign a written informed consent form. Participation can be ended at any time during the clinical trial if a participant refuses to continue or if there is significant clinical deterioration, as determined by the KMDs. The study findings will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals and presented at national and international conferences.

Discussion

EA is commonly used for pain management after surgery.44–47 There has been a systematic review summarising the current evidence concerning the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating acute postoperative pain after back surgery,17 but few clinical trials have evaluated the effectiveness of EA for treating non-acute postoperative pain after back surgery. We have therefore designed this pilot RCT to guide the design of a full-scale randomised trial. The results of our study will determine the appropriate sample size for a future feasible, pragmatic, comparative effectiveness RCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of EA with UC compared with UC alone in the treatment of non-acute pain after back surgery. From the subgroup analysis of the type of surgery and the surgically involved level of spine, we will explore the potential factor(s) related to the difference of effectiveness of EA on pain and function after back surgery.

A strength of our study is that it is designed to be a feasible, comparative effectiveness trial design that is similar to common clinical situations. Additionally, this clinical trial protocol was conducted to conform strictly to the STRICTA statement23 and the CONSORT statement.24 We expect that this pilot study will provide the clinical basis and information that is required to assess the feasibility of a future large-scale trial.

Trial status

The trial is currently in the recruitment phase. The results of this trial will be available in 2015.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr SeungHoon Choi for providing helpful advice for the trial implementation. The authors would also like to express appreciation for the contributions from patients with pain after back surgery who will participate in this trial.

Footnotes

Contributors: M-SH helped to conceive and design the trial and wrote the manuscript. K-HH and H-WC helped to conceive of and design the trial. B-CS helped to conceive the trial and revised the manuscript. H-YL and IH will recruit the patients and conduct the trial. N-KK planned the statistical analysis. B-KC and D-WS will supervise the trial. E-HH helped to conceive and design the study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, 2013(K14273).

Competing interests: None.

Patients consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Pusan National University Korean Hospital in September 2013 (IRB approval number 2013012).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We will share the data after the trial is finished. Additional details of the study protocol can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Don AS, Carragee E. A brief overview of evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with surgery. Spine J 2008;8:258–65. 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarrazin JL. Imaging of postoperative lumbar spine. J Radiol 2003;84(2 Pt 2):241–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrera Herrera I, Moreno de la Presa R, Gonzalez Gutierrez R et al. . Evaluation of the postoperative lumbar spine. Radiologia 2013;55:12–23. 10.1016/j.rx.2011.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aghion D, Chopra P, Oyelese AA. Failed back syndrome. Med Health R I 2012;95:391–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skolasky RL, Wegener ST, Maggard AM et al. . The impact of reduction of pain after lumbar spine surgery: the relationship between changes in pain and physical function and disability. Spine 2014;39:1426–32. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleckenstein J, Baeumler PI, Gurschler C et al. . Acupuncture for post anaesthetic recovery and postoperative pain: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:292 10.1186/1745-6215-15-292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchison RW, Chon EH, Tucker WF Jr et al. . A comparison of a fentanyl, morphine, and hydromorphone patient controlled intravenous delivery for acute postoperative analgesia: a multicenter study of opioid-induced adverse reactions. Hosp Pharm 2006;41:659–63. 10.1310/hpj4107-659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S et al. . Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008;11(2 Suppl):S105–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A et al. . Survey of adverse events following acupuncture (SAFA): a prospective study of 32,000 consultations. Acupunct Med 2001;19:84–92. 10.1136/aim.19.2.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheway J, Agbabiaka TB, Ernst E. Patient safety incidents from acupuncture treatments: a review of reports to the National Patient Safety Agency. Int J Risk Saf Med 2012;24:163–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin CW, Haas M, Maher CG et al. . Cost-effectiveness of guideline-endorsed treatments for low back pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 2011;20:1024–38. 10.1007/s00586-010-1676-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JH, Choi TY, Lee MS et al. . Acupuncture for acute low back pain: a systematic review. Clin J Pain 2013;29:172–85. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31824909f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin JS, Ha IH, Lee J et al. . Effects of motion style acupuncture treatment in acute low back pain patients with severe disability: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, comparative effectiveness trial. Pain 2013;154:1030–7. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casimiro L, Barnsley L, Brosseau L et al. . Acupuncture and electroacupuncture for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(4):CD003788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao XB, Xing QZ, Han XC. Observation on electroacupuncture at neimadian (extra) and neiguan (PC 6) for analgesia after thoracic surgery. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2013;33:829–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chia KL. Electroacupuncture treatment of acute low back pain: unlikely to be a placebo response. Acupunct Med 2014;32:354–5. 10.1136/acupmed-2014-010582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho YH, Kim CK, Heo KH et al. . Acupuncture for acute postoperative pain after back surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Pract 2014. Published Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang HT, Zheng SH, Feng J et al. . Thin's abdominal acupuncture for treatment of failed back surgery syndrome in 20 cases of clinical observation. Guide J Tradit Chin Med Pharm 2012;18:63–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng SH, Wu YT, Liao JR et al. . Abdominal acupuncture treatment of failed back surgery syndrome clinical observation [in Chinese]. J Emerg Tradit Chin Med 2010;19:1497–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SI, Lee KB, Lee HS et al. . Acupuncture experience in patients with chronic low back pain(2): a qualitative study—focused on participants in randomized controlled trial. Korean J Acupunct 2012;29:581–97. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H, Bang H, Kim Y et al. . Non-penetrating sham needle, is it an adequate sham control in acupuncture research? Complement Ther Med 2011;19(Suppl 1):S41–8. 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Guideline Clearinghouse. Low back disorders. Secondary low back disorders 2011. http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=38438

- 23.MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R et al. . Revised STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. J Evid Based Med 2010;3:140–55. 10.1111/j.1756-5391.2010.01086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF et al. . CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg 2012;10:28–55. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins J, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung YP, Jung HK, Chiang SY et al. . The clinical study of electroacupuncture treatment at Hua-Tuo-Jia-Ji-Xue on spondylolisthesis. J Korean Acupunct Moxibustion Soc 2008;25:221–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dias M, Vellarde GC, Olej B et al. . Effects of electroacupuncture on stress-related symptoms in medical students: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Acupunct Med 2014;32:4–11. 10.1136/acupmed-2013-010408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim KH, Ryu JH, Park MR et al. . Acupuncture as analgesia for non-emergent acute non-specific neck pain, ankle sprain and primary headache in an emergency department setting: a protocol for a parallel group, randomised, controlled pilot trial. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004994 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Revill SI, Robinson JO, Rosen M et al. . The reliability of a linear analogue for evaluating pain. Anaesthesia 1976;31:1191–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1976.tb11971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain 1983;16:87–101. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90088-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 2000;25:2940–52. 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeon CH, Kim DJ, Kim SK et al. . Validation in the cross-cultural adaptation of the Korean version of the Oswestry Disability Index. J Korean Med Sci 2006;21:1092–7. 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.6.1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337–43. 10.3109/07853890109002087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang EJ, Shin SH, Park HJ et al. . A validation of health status using EQ-5D. Korean J Health Econ Policy 2006;12:19–43. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markowski A, Sanford S, Pikowski J et al. . A pilot study analyzing the effects of Chinese cupping as an adjunct treatment for patients with subacute low back pain on relieving pain, improving range of motion, and improving function. J Altern Complement Med 2014;20:113–17. 10.1089/acm.2012.0769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan CG, Gray HG, Newton M et al. . Pain biology education and exercise classes compared to pain biology education alone for individuals with chronic low back pain: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Man Ther 2010;15:382–7. 10.1016/j.math.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harden RN, Remble TA, Houle TT et al. . Prospective, randomized, single-blind, sham treatment-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of an electromagnetic field device for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a pilot study. Pain Pract 2007;7:248–55. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2007.00145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A. The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2003;12:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostelo RW, de Vet HC. Clinically important outcomes in low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005;19:593–607. 10.1016/j.berh.2005.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molsberger AF, Mau J, Pawelec DB et al. . Does acupuncture improve the orthopedic management of chronic low back pain––a randomized, blinded, controlled trial with 3 months follow up. Pain 2002;99:579–87. 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00269-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JH, Kim EJ, Seo BK et al. . Electroacupuncture for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: study protocol for a pilot multicentre randomized, patient-assessor-blinded, controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:254 10.1186/1745-6215-14-254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Man SC, Hung BH, Ng RM et al. . A pilot controlled trial of a combination of dense cranial electroacupuncture stimulation and body acupuncture for post-stroke depression. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:255 10.1186/1472-6882-14-255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puri KS, Suresh KR, Gogtay NJ et al. . Declaration of Helsinki, 2008: implications for stakeholders in research. J Postgrad Med 2009;55:131–4. 10.4103/0022-3859.52846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chi H, Zhou WX, Wu YY et al. . Electroacupuncture intervention combined with general anesthesia for 80 cases of heart valve replacement surgery under cardiopulmonary bypass. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu 2014;39:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu J, Zhao Y, Yang CM et al. . Effects of electroacupuncture preemptive intervention on postoperative pain of mixed hemorrhoids. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2014;34:279–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Wang L, Zhang M et al. . Effects of electroacupuncture on postoperative functional recovery in patients with gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2014;34:273–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z, Wang C, Li Q et al. . Electroacupuncture at ST36 accelerates the recovery of gastrointestinal motility after colorectal surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med 2014;32:223–6. 10.1136/acupmed-2013-010490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.