Abstract

The assessment of patterns in macroecology, including those most relevant to global biodiversity conservation, has been hampered by a lack of quantitative data collected in a consistent manner over the global scale. Global analyses of species’ abundance data typically rely on records aggregated from multiple studies where different sampling methods and varying levels of taxonomic and spatial resolution have been applied. Here we describe the Reef Life Survey (RLS) reef fish dataset, which contains 134,759 abundance records, of 2,367 fish taxa, from 1,879 sites in coral and rocky reefs distributed worldwide. Data were systematically collected using standardized methods, offering new opportunities to assess broad-scale spatial patterns in community structure. The development of such a large dataset was made possible through contributions of investigators associated with science and conservation agencies worldwide, and the assistance of a team of over 100 recreational SCUBA divers, who undertook training in scientific techniques for underwater surveys and voluntarily contributed skills, expertise and their time to data collection.

Background & Summary

Understanding how life is distributed on earth and how these patterns are shaped by the environment, including interactions between species, have been key goals in biology for centuries1–3,1–3,1–3, while biodiversity conservation has provided an additional motivation for understanding spatial patterns in nature and linking these to human impacts. The recent increase in the availability of broad-scale biological data, particularly in the form of extraordinarily large online databases such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and the Ocean Biogeographic Information System (OBIS), has re-invigorated investigation into the distribution of life on earth in relation to environmental drivers4,5, and fuelled the growing study of macroecology6,7. However, these virtual collections of records lack the quantitative abundance information that is particularly important for biodiversity conservation applications. For example, opportunities for reliable assessment of species for the IUCN Red List are greatly reduced without abundance information, and using range maps based on presence-only records to prioritize conservation planning can lead to protection of marginal habitat8.

A shortage of resources and coordination across political boundaries has limited collection of broad-scale quantitative biodiversity datasets. However, even the largest, most expensive, multi-national scientific projects have not provided consistently collected abundance data at a global scale for any community type. For example, the US$650 million 10-year Census of Marine Life, while achieving enormous gains in understanding the variety of life in the sea, fell short in progress towards one of its goals—to estimate the abundance of marine life9.

Established in 2007 as a means to overcome the shortage of resources and capacity to provide quantitative data on marine species over large temporal and spatial scales, the Reef Life Survey (RLS) program has involved data collection by an international network of trained volunteer (or ‘citizen’) scientists and professional biologists largely acting in a voluntary capacity. Focussing on quality of outputs and consistency of data through selective inclusion and training of volunteer participants, rather than broader engagement of all interested, RLS fills a niche between other citizen science programs and large-scale professional initiatives such as the Census of Marine Life. The RLS program represents a marine analogue to well-organized and large-scale amateur bird watching programs (e.g., eBird and the Christmas Bird Count), but with a more structured quantitative sampling methodology than most. Through the long term, it aims to provide a biological equivalent to the synoptic picture of the physical parameters generated for the world’s oceans through sensor networks such as the ARGO float array10 and the Australian Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS).

Here we describe the global reef fish dataset collected by the Reef Life Survey program, which can be used to assess large-scale spatial patterns in diversity and community structure, and as a baseline for comparison with future surveys, to address long-standing ecological questions or conservation goals. These data have already been used to describe global patterns in reef fish functional diversity11 and have provided the most comprehensive empirical assessment of key features for successful marine protected area (MPA) design and management12. The dataset described here includes all survey sites analysed for the latter study, with the exception of data collected using the same methodology from 107 sites that were provided to us for analysis but belong to other organisations or are otherwise confidential. Some transects surveyed at different depths at the same site, but on different days, have also been excluded from this dataset, which only includes surveys from the latest date (at the time of writing) at any given site. A summary of survey effort and key diversity values by ecoregion13 is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of taxonomic richness and abundance information by ecoregion.

| Ecoregion | Transects (Sites) | Taxa (total) | Taxa (mean) | Abundance (mean) | Ecoregion | Transects (Sites) | Taxa (total) | Taxa (mean) | Abundance (mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean values relate to 500 m2 transect areas, and abundance is the summed abundance of all taxa recorded within each transect. | |||||||||

| Adriatic Sea | 4 (2) | 14 | 9 | 219 | Manning-Hawkesbury | 246 (130) | 263 | 21 | 1291 |

| Agulhas Bank | 24 (11) | 37 | 9 | 264 | Marquesas | 9 (7) | 112 | 48 | 3042 |

| Arnhem Coast to Gulf of Carpenteria | 16 (8) | 100 | 29 | 651 | Nicoya | 171 (90) | 144 | 25 | 2316 |

| Azores Canaries Madeira | 100 (44) | 60 | 10 | 693 | Ningaloo | 54 (30) | 271 | 46 | 1005 |

| Bassian | 472 (227) | 155 | 7 | 268 | North and East Barents Sea | 3 (2) | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Bismarck Sea | 10 (10) | 250 | 84 | 5578 | North Patagonian Gulfs | 14 (9) | 9 | 4 | 222 |

| Bonaparte Coast | 23 (16) | 100 | 19 | 451 | North Sea | 12 (6) | 15 | 5 | 186 |

| Cape Howe | 458 (171) | 232 | 18 | 1029 | Northeastern New Zealand | 209 (102) | 79 | 12 | 868 |

| Celtic Seas | 15 (8) | 22 | 5 | 110 | Northern and Central Red Sea | 13 (13) | 146 | 54 | 4195 |

| Central and Southern Great Barrier Reef | 120 (53) | 548 | 50 | 2368 | Northern California | 14 (8) | 30 | 12 | 117 |

| Central Kuroshio Current | 15 (9) | 80 | 20 | 1159 | Oyashio Current | 6 (5) | 9 | 2 | 150 |

| Channels and Fjords of Southern Chile | 10 (8) | 7 | 2 | 4 | Panama Bight | 74 (40) | 126 | 27 | 2425 |

| Chiapas-Nicaragua | 22 (14) | 78 | 23 | 456 | Phoenix/Tokelau/Northern Cook Islands | 24 (12) | 138 | 41 | 3266 |

| Chiloense | 15 (9) | 7 | 3 | 253 | Puget Trough/Georgia Basin | 15 (8) | 21 | 7 | 166 |

| Cocos Islands | 42 (23) | 93 | 29 | 2068 | Rapa-Pitcairn | 6 (5) | 96 | 43 | 1039 |

| Cocos-Keeling/Christmas Island | 15 (15) | 231 | 66 | 3823 | Samoa Islands | 48 (25) | 247 | 39 | 1112 |

| Coral Sea | 36 (18) | 341 | 58 | 759 | Sea of Japan/East Sea | 10 (6) | 17 | 4 | 278 |

| East African Coral Coast | 9 (9) | 176 | 53 | 1160 | Seychelles | 13 (12) | 183 | 59 | 1064 |

| East Greenland Shelf | 2 (1) | 2 | 2 | 2 | Shark Bay | 7 (6) | 107 | 38 | 2583 |

| Easter Island | 27 (17) | 44 | 18 | 492 | Society Islands | 21 (17) | 202 | 50 | 1068 |

| Eastern Brazil | 21 (10) | 50 | 22 | 712 | Solomon Archipelago | 5 (5) | 217 | 100 | 7505 |

| Exmouth to Broome | 55 (27) | 303 | 41 | 1503 | South Australian Gulfs | 162 (58) | 92 | 13 | 349 |

| Fiji Islands | 17 (9) | 181 | 42 | 652 | South Kuroshio | 9 (8) | 193 | 57 | 1088 |

| Floridian | 32 (17) | 117 | 36 | 1433 | Southern California Bight | 23 (7) | 36 | 13 | 364 |

| Greater Antilles | 3 (1) | 49 | 32 | 957 | Southern Caribbean | 14 (14) | 88 | 39 | 4656 |

| Guayaquil | 19 (15) | 69 | 24 | 636 | Southern Cook/Austral Islands | 26 (15) | 195 | 43 | 1225 |

| Gulf of Maine/Bay of Fundy | 3 (2) | 1 | 1 | 93 | Southwestern Caribbean | 59 (22) | 140 | 33 | 1003 |

| Gulf of Thailand | 7 (7) | 101 | 38 | 2165 | Three Kings-North Cape | 13 (6) | 30 | 11 | 366 |

| Hawaii | 11 (9) | 90 | 26 | 234 | Tonga Islands | 42 (30) | 336 | 48 | 1048 |

| Houtman | 70 (31) | 146 | 18 | 478 | Torres Strait Northern Great Barrier Reef | 36 (18) | 340 | 70 | 3190 |

| Kermadec Island | 29 (14) | 56 | 21 | 1400 | Tuamotus | 59 (52) | 318 | 60 | 2658 |

| Leeuwin | 151 (69) | 179 | 20 | 854 | Tweed-Moreton | 80 (37) | 365 | 33 | 1485 |

| Lesser Sunda | 11 (11) | 292 | 86 | 4274 | Vanuatu | 1 (1) | 68 | 68 | 837 |

| Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands | 223 (97) | 350 | 28 | 1084 | Western Bassian | 7 (6) | 23 | 9 | 49 |

| Maldives | 12 (12) | 198 | 68 | 1607 | Western Mediterranean | 52 (28) | 57 | 12 | 623 |

| Malvinas/Falklands | 5 (5) | 7 | 3 | 15 | Western Sumatra | 52 (30) | 347 | 69 | 2468 |

Methods

Survey methods

The RLS global reef fish dataset includes data from 1,879 sites, collected using standard RLS survey methods, described in detail in an online methods manual (Reef Life Survey methods manual. http://reeflifesurvey.com/files/2008/09/NEW-Methods-Manual_15042013.pdf). Surveys involve underwater visual census (UVC) by SCUBA divers along a 50 m transect line, laid along a depth contour on hard substrate (coral or rocky reef). All fish species observed within 5 m of the transect line were recorded on a waterproof datasheet as the diver swam slowly along the line (at approximately 2 m/min).

Abundance estimates were made by keeping a tally of individuals of less abundant species and, in locations with high fish densities, estimating the number of more abundant species. Abundances of schooling fishes were recorded by counting a subset within the school which was combined with an estimate of the proportion of the total school. In coral reefs with high fish species richness and densities, the order of priority for recording accurately was to first ensure all species observed along transects were included, then tallies of individuals of larger or rare species, then finally estimates of abundance for more common species. Only divers with the most extensive and appropriate experience undertook surveys in diverse coral reefs.

Nearly all fishes observed were identified to species level, with photographs of unknown species taken with an underwater digital camera for later identification using appropriate field guides and consultation with taxonomic experts for the particular group, as necessary. When species level identification was not possible, records were classified at the highest taxonomic resolution possible given the information available and experience of the observer. In total, 1.8% of records in the RLS global reef fish dataset were not at the species level (i.e., are at genus level or higher).

Fishes within 5 m of the line were recorded separately for each side of the transect line, with each side referred to as a ‘block’. Thus, two blocks form a complete transect (also referred to as an individual survey). Multiple transects were usually surveyed at each site (global mean 1.98±0.03 SE transects per site, min=1, max=9), usually along different depth contours (mean depth 7.28 m±0.07 SE, min=0.1, max=42). Sites are distinguished by unique site codes with latitude and longitude recorded in decimal degrees (WGS84) using a handheld GPS unit, or occasionally taken from Google Earth.

Quality control

Data in the RLS global reef fish dataset were collected by a combination of experienced scientists and skilled recreational divers, with all divers having either substantial prior experience in reef fish surveys or extensive training in the RLS methods. Screening of interested divers was undertaken before training so that only the most committed and capable divers with appropriate SCUBA experience were invited to participate. Although a minimum of 50 dives’ experience was used as a standard in diver selection, a survey of RLS divers in 2010 indicated that most RLS divers had completed over 300 dives. For divers without prior formal scientific training, one-on-one instruction in survey methods and assistance with species identification was provided during a training course typically lasting four to five days, but up to two weeks (depending on local marine life and skills of the diver). During these courses, trainees undertook practice surveys with an experienced scientist, who carefully compared their data following each dive, with a final approval given after data were considered to be of high consistency with the trainer. A formal comparison of data collected by divers without tertiary scientific training with data collected by experienced scientists showed that the variation between recreational and scientific divers was non-significant and negligible in comparison to other sources of variation within and between sites14. The vast majority of divers who contributed data to this dataset were trained by the authors. Data collected during training were not added to the database.

Following each survey, each RLS diver transcribed their data from the underwater datasheets onto custom data entry forms in Microsoft Excel. This was usually done the same day as survey dives were undertaken. Excel data entry templates contained lookups from region-specific species lists and were in a consistent format for uploading to the RLS database. Data checks were made upon upload to the database, including for data structure (and completeness) and consistency in metadata among divers, as well as checks designed to detect species not previously recorded by RLS divers in that particular region. Any species added that was previously not in the RLS database for that region prompted querying of those particular data points, and taxonomic and distributional data were also checked before addition of new species.

Consistency in data collection was continually emphasized, and was assisted by continued participation of the same divers over time. Further to this, the authors participated in surveys over many ecoregions (59 of 72 collectively), collecting 35.1% of all data in the dataset, and thus providing a substantial element of consistency in diver participation at the global scale.

Data collection mechanisms

This dataset was compiled from data collected in a combination of collaborative surveys with scientific colleagues worldwide, targeted RLS field campaigns and ad-hoc local surveys by trained RLS divers at their regular dive sites or when on holidays. Field campaigns involved small groups of divers (usually 4 to 8) undertaking survey dives over a period of four days to two weeks (or occasionally longer) under the direction and supervision of a scientist or experienced survey diver (mostly one of the authors). At the conclusion of each field campaign, one of the RLS organizers or scientists leading the trip collated data from participants and undertook manual checks of the data. These checks included close scrutiny of species lists, abundances and site details. Evidence in the form of images was typically requested for records of species not seen by the experienced surveyor on the trip, with such evidence essential for divers with less experience in that particular region. Uncertain records or records of new species for regions for which definitive evidence was not available were reduced to the highest taxonomic resolution for which there was confidence (usually genus). For ad-hoc surveys by trained divers outside of group field campaigns, species identification assistance and data transfer occurred via email, and all the data checks were made by a scientist in the office before uploading data to the database.

Data Records

Data record 1

The RLS reef fish dataset is managed in a live database, and thus any errors are corrected as identified and taxonomic details updated as appropriate. It is accessible in comma-separated format on the Reef Life Survey website: www.reeflifesurvey.com (Data Citation 1), containing the data fields outlined in Table 2. We strongly recommend the use of this ‘live’ dataset over the archived version described below as Data Record 2, and would appreciate that any errors identified by users of the dataset be reported to the corresponding author to enable correction where necessary, allowing improvement for subsequent users.

Table 2. Key to the data fields in the Reef Life Survey reef fish dataset.

| Data field | Description | Values |

|---|---|---|

| SiteCode | Identifier of unique geographical coordinates | Usually 2–3 letters followed by numeric string |

| Site | Descriptive name of the site | |

| SiteLat | Latitude of site (WGS84) | Decimal degrees |

| SiteLong | Longitude of site (WGS84) | Decimal degrees |

| Country | Country (or largely-autonomous state) | |

| Ecoregion | Location within the Marine Ecoregions of the World provided in Spalding et al.13 | |

| Realm | Biogeographic realm as classified in the Marine Ecoregions of the World13 | |

| SurveyID | Identifier of individual 50 m transects | Numeric string |

| Depth | Mean depth of transect line as recorded on dive computer (note: this does not account for tide or deviations from the mean value as a consequence of imperfect tracking of the depth contour along the bottom) | metres |

| SurveyDate | Date of survey | (dd-month-yy) |

| Diver | Initials of the diver who collected the datum | Two to four letter unique identifier |

| Taxon | Species name, corrected for recent taxonomic changes and grouping of records not at species level | |

| Family | Taxonomic family | |

| Block | Identifies which 5 m wide block (of two) within each complete transect (surveyID) | Values=1 (block on deeper/offshore side of transect line), 2 (block on shallower/inshore side) |

| Total | Total abundance for record on that block, transect, site, date combination | Numeric string |

Data record 2

An archival version of the RLS reef fish dataset, in the same format (comma-separated) and the same fields as described above, has been deposited in figshare (Data Citation 2). Details of the data fields provided in Table 2 are also provided in csv format associated with this data record.

Technical Validation

All methods to estimate fish densities involve biases. For UVC methods, as used to collect RLS data, biases have been explored and include species-specific avoidance or attraction to divers and influences of habitat, visibility or species’ physical and behavioural characteristics on detectability15–17,15–17,15–17. Differences between divers have also been noted to contribute to variation in UVC data18,19, although this variation is generally small compared to that associated with the spatial and temporal factors of interest such as site, region or month14,15.

We consider that, among the available methods for non-destructive sampling of marine fish communities, the UVC method applied here provides the most efficient means to cover the diverse range of assemblages, micro-habitats and conditions associated with the world’s coral and rocky reefs. It must be noted, however, that the densities of diver-shy species will consistently be under-estimated, while densities of species attracted to divers will be over-estimated, and the net effect of these on total fish density at any given site will depend on the local species composition. Habitat characteristics can potentially affect species detectability; however, in an experiment in which a macroalgal forest was cleared, the difference in detectability between vegetated and open reef was found to be negligible for five of six fish species15. In summary, given a range of biases, data should not be regarded as providing accurate estimates of fish density within transect blocks; however, biases are largely systematic at the species level, and data can be used for relative comparisons, such that if counts of a species double between sites, then underlying densities can also be regarded as doubling.

Usage Notes

There are a few important considerations for usage of the RLS global reef fish dataset (field names are described in Table 2):

The level of spatial aggregation of data. The base unit in the data is a transect block (250 m2). There are always two adjacent blocks per complete transect (surveyID), which can be summed to form a standard 500 m2 survey area. However, multiple transects are usually surveyed within each site (SiteCode), and the number of transects differs between sites. Given blocks, and even transects, within a site are not independent of one another, analysis of patterns among sites should consider spatial autocorrelation at the site scale. Options include aggregating data across blocks and transects within each site (e.g., calculating mean densities per 250 m2 or 500 m2), or adding SiteCode as a nested spatial factor in statistical models and using summed values within each 500 m2 transect. If aggregating data across multiple transects per site, consideration should be given to the accumulation of species in the sample with each additional transect (see consideration 2 below).

Species richness or diversity estimates will be biased by the varying number of transects surveyed at each site if not calculated consistently at the block or transect (surveyID) level first (or if fixed coverage sampling methods are not used).

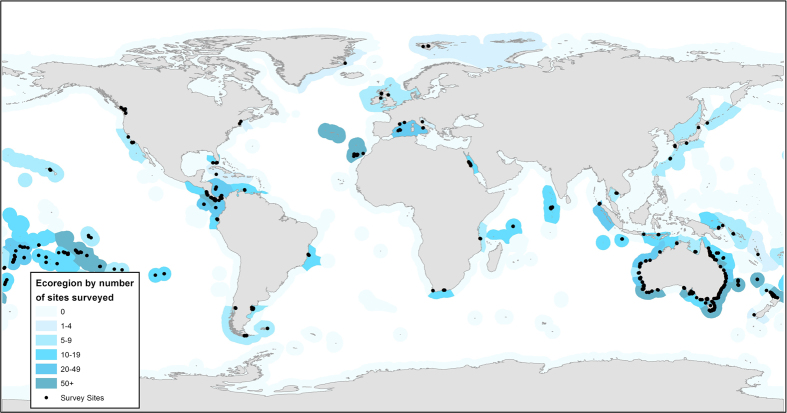

Spatial bias. The Australian continent is much better sampled than other parts of the world, while high-latitude areas are poorly covered, with no survey data from Antarctica. Table 1 lists the number of surveys and sites within each ecoregion and provides a quick guide to coverage within any given ecoregion. Likewise, Figure 1 and the site map on the RLS website (www.reeflifesurvey.com) can be used for a quick visual overview. Site latitude (SiteLat) and longitude (SiteLong) data are readily extracted from the dataset for conversion to kml files and display in Google Earth.There are also many other considerations which are common to any dataset of this nature. These are not described in detail here, but a few examples include:

Spatial autocorrelation (i.e., sites in close proximity exhibit closer relationships than sites at distance) should be considered for many analyses as data are highly clumped.

Consideration should be given to assumptions relating to species detectability for some studies, including whether differences in detectability due to physical appearance, behaviour or abundance may affect conclusions.

Abundance data have a long distribution tail, and factors typically act in a multiplicative rather than additive way (e.g., a change from 5–10 is more ecologically comparable to a change from 50–100 than from 50–55), so log transformation of abundance data is appropriate in most cases.

Figure 1. The distribution of sites included in the Reef Life Survey reef fish dataset (black circles).

Many sites are overlapping. Marine Ecoregions of the World13 have been colour-coded to reflect the density of sites surveyed within.

The analyses of this dataset described in associated papers11,12 used community level metrics (e.g., diversity values) calculated per transect or block, and averaged across transects within each site. We also found the random forest methods used to model community metrics in these papers to be robust to spatial autocorrelation.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Edgar, G. J. & Stuart-Smith, R. D. Systematic global assessment of reef fish communities by the Reef Life Survey program. Sci. Data 1:140007 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2014.7 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the many Reef Life Survey (RLS) divers who contributed to data collection (who are named on the RLS website), and Antonia Cooper, Just Berkhout, Marlene Davey, Jemina Stuart-Smith, Sylvia Buchanan, James Brook, Elizabeth Oh, Paul Day, Kevin Smith, Stuart Kininmonth, Jacqui Pocklington and Andy Myers for assistance with RLS projects and data management, and Sophie Edgar for preparing the map in Figure 1. Development of the RLS dataset was supported by the former Commonwealth Environment Research Facilities Program, while additional support from the Australian Research Council, a Fulbright Visiting Scholarship (to GJE), a Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Fellowship (to RSS), the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, and the Marine Biodiversity Hub, a collaborative partnership funded under the Australian Government’s National Environmental Research Program, have assisted in its expansion and management. We also acknowledge funding from the National Geographic Society, Conservation International, Wildlife Conservation Society, Winifred Violet Scott Trust, The Ian Potter Foundation, Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service, University of Tasmania and ASSEMBLE Marine for field surveys.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Citations

- Reef Life Survey 2014. Public Website. www.reeflifesurvey.com

- Reef Life Survey 2014. Figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.934319

References

- Gaston K. J. Global patterns in biodiversity. Nature 405, 220–227 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford S., D’Hondt S., Prell W. Environmental controls on the geographic distribution of zooplankton diversity. Nature 400, 749–753 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Connell J. H., Orias E. The ecological regulation of species diversity. Am. Nat. 98, 399–414 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- Tittensor D. P. et al. Global patterns and predictors of marine biodiversity across taxa. Nature 466, 1098–1101 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanne A. E. et al. Three keys to the radiation of angiosperms into freezing environments. Nature 506, 89–92 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. H., Maurer B. A. Macroecology: the division of food and space among species on continents. Science 243, 1145–1150 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K. J., Blackburn T. M. A critique for macroecology. Oikos 84, 353–368 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. et al. Prioritizing global marine mammal habitats using density maps in place of range maps. Ecography 37, 212–220 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Pauly D., Froese R. A count in the dark. Nat. Geosci. 3, 662–663 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda S., Ohira T., Nakamura T. A monthly mean dataset of global oceanic temperature and salinity derived from Argo float observations. JAMSTEC Rep. Res. Dev. 8, 47–59 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Stuart-Smith R. D. et al. Integrating abundance and functional traits reveals new global hotspots of fish diversity. Nature 501, 539–542 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar G. J. et al. Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features. Nature 506, 216–220 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding M. D. et al. Marine ecoregions of the world: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. Bioscience 57, 573–583 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Edgar G. J., Stuart-Smith R. D. Ecological effects of marine protected areas on rocky reef communities: a continental-scale analysis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 388, 51–62 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Edgar G. J., Barrett N. S., Morton A. J. Biases associated with the use of underwater visual census techniques to quantify the density and size-structure of fish populations. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 308, 269–290 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil M. A. et al. Accounting for detectability in reef-fish biodiversity estimates. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 367, 249–260 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Paige C., Mills Flemming J., Lotze H. K. Overestimating fish counts by non-instantaneous visual censuses: consequences for population and community descriptions. PLoS ONE 5, e11722 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A. A., Mapstone B. D. Observer effects and training in underwater visual surveys of reef fishes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 154, 53–63 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Bernard A. T. F., Götz A., Kerwath S. E., Wilke C. G. Observer bias and detection probability in underwater visual census of fish assemblages measured with independent double-observers. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 443, 75–84 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Reef Life Survey 2014. Public Website. www.reeflifesurvey.com

- Reef Life Survey 2014. Figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.934319