Abstract

Understanding the metabolic factors that contribute to energy metabolism (EM) is critical for the development of new treatments for obesity and related diseases. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is not perfectly coupled to ATP synthesis, and the process of proton-leak plays a crucial role. Proton-leak accounts for a significant part of the resting metabolic rate (RMR) and therefore enhancement of this process represents a potential target for obesity treatment. Since their discovery, uncoupling proteins have stimulated great interest due to their involvement in mitochondrial-inducible proton-leak. Despite the widely accepted uncoupling/thermogenic effect of uncoupling protein one (UCP1), which was the first in this family to be discovered, the reactions catalyzed by its homolog UCP3 and the physiological role remain under debate. This review provides an overview of the role played by UCP1 and UCP3 in mitochondrial uncoupling/functionality as well as EM and suggests that they are a potential therapeutic target for treating obesity and its related diseases such as type II diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: uncoupling protein, energy metabolism, mitochondria, proton-leak, obesity

Introduction

Mitochondria are the major regulators of cellular energy metabolism (EM). Alterations of mitochondrial functionality have been linked to the pathogenesis of some metabolic disorders, including obesity and type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

The principal function of mitochondria is ATP production. Reduced cofactors, such as NADH and FADH2, obtained from oxidizable molecules (carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins) supply electrons to the electron transport chain (ETC) and result in a final reduction of molecular oxygen to water. Electron transfer through the ETC controls pumping of protons (H+) from the matrix to the intermembrane space, thus creating a proton-motive force (Δp), whose energy is used by ATP synthase for the phosphorylation of ADP.

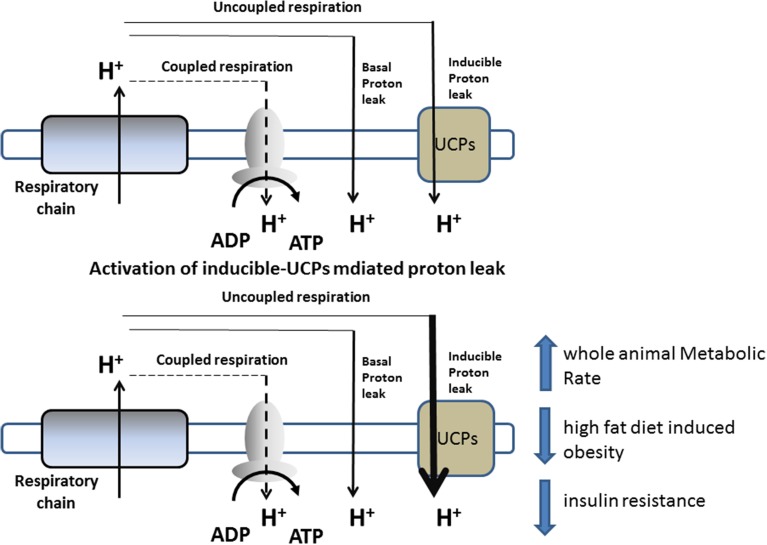

Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is not perfectly coupled to ATP synthesis, since a portion of the energy liberated from the oxidation of dietary energy substrates is lost as heat instead of being converted into ATP. Indeed, some of the energy present in Δp dissipates as heat by the re-entry of H+ into the matrix, through pathways independent of ATP synthase (proton-leak). Proton-leak is the sum of two processes: basal- and inducible proton-leak (Brand and Esteves, 2005). The first is not acutely regulated, but rather depends on the fatty-acyl composition of the mitochondrial inner membrane and the presence of adenine nucleotide translocase. On the other hand, inducible proton-leak is acutely controlled, with uncoupling proteins playing a crucial role (Divakaruni and Brand, 2011) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of proton-leak and of the proposed role of UCPs in influencing energy metabolism.

Proton-leak has a marked influence on the entire EM of an organism, and, in rats, accounts for approximately 20–30% of the resting metabolic rate (RMR) (Rolfe and Brand, 1996). Variations in the proton-leak process contribute to the development of obesity or weight loss (Harper et al., 2008), and thus there has been increasing interest in targeting this process in order to increase RMR to treat obesity and other related diseases (Figure 1).

The present review discusses the relevance of UCPs on influencing EM. In particular, it focuses on uncoupling protein one (UCP1) and UCP3 due to their expression in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and skeletal muscle (SkM), respectively, which significantly contributes to EM.

Uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1)

UCPs are members of the mitochondrial anion carrier family. The first uncoupling protein identified, UCP1, is predominantly expressed in BAT where it represents approximately 10% of the mitochondrial protein content and plays a thermogenic role through the catalysis of proton-leak. Recent evidence indicates the existence of two types of thermogenic adipocytes expressing UCP1: the classical brown adipocytes, which are found in the intercapsular brown adipose organ, and beige/bright adipocytes, which are found in subcutaneous WAT. Only recently it has unequivocally been proven that UCP1-positive cells found in WAT (i.e., beige adipocytes) are thermogenic-competent (Shabalina et al., 2013) and are actually a distinct subpopulation of white adipocytes that originate from a different lineage (reviewed in Harms and Seale, 2013).

One of the most prominent differences between brown and beige adipocytes is that brown cells express high levels of UCP1 and other thermogenic genes under basal (unstimulated) conditions, whereas beige adipocytes only express these genes in response to activators, such as β-adrenergic and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonists (Petrovic et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2013; Carrière et al., 2014). Nevertheless, both adipocyte types show comparable levels of UCP1 upon stimulation, indicating that under specific conditions they may have the same thermogenic capacity (Wu et al., 2012).

Cold and overfeeding are physiological stimuli that influence BAT thermogenesis through the enhancement of sympathetic overflow to BAT (Cannon and Nedergard, 2004). Acute sympathetic nerve activation stimulates heat production by activating UCP1 function. Indeed, noradrenergic stimulation of brown adipocytes activates cAMP-linked signaling pathways, which results in increased (i) mitochondria number and size, (ii) UCP1 gene transcription and translation, and (iii) UCP1 thermogenic activity through activation of lipolysis and release of acute regulators of UCP1, such as free fatty acids.

Prolonged cold exposure stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of brown precursor cells to expand BAT mass and increase thermogenic capacity (Bukowiecki et al., 1982). Moreover, it also induces beige adipocyte development and function (Vitali et al., 2012). Although sympathetic nerve activity was previously thought to be the major physiological signal that activates BAT thermogenesis and induces beige adipocyte development, numerous hormones and factors have now been shown to regulate such processes. Moreover, brown and beige adipocytes can be selectively recruited and activated (for review Cannon and Nedergard, 2004; Harms and Seale, 2013). The molecular mechanisms of UCP1 activation have been comprehensively discussed in other recent reviews and will not be elaborated upon here (Klingenberg and Echtay, 2001; Porter, 2008).

Role of UCP1 in energy metabolism

The presence of UCP1 provides a marked capacity for BAT to dissipate energy by as much as 20%. In rodents, overeating activates BAT “diet-induced thermogenesis,” that preserve energy balance and contrasts obesity by reducing metabolic efficiency (Cannon and Nedergard, 2004). The overexpression of UCP1 or activation of BAT thermogenesis has been shown to prevent the development of obesity (Krauss et al., 2005). In contrast, the first experiments performed on UCP−/−1 mice housed at a standard temperature (20–22°C) failed to show an enhanced obesity predisposition compared to their wild-type counterparts (Enerback et al., 1997). More recently, Feldmann et al. (2009) reported that UCP1 ablation induced obesity in mice housed at 30°C, i.e., the thermoneutral temperature at which mice facultative thermogenesis is kept at a minimum. Indeed, when housed at 20–22°C, mice are under chronic thermal stress and inevitably increase their metabolic rate (~50%) to maintain body temperature (Golozoubova et al., 2006). Therefore, UCP−/−1 mice, that are unable to enhance BAT thermogenesis, have necessarily expend extra energy to defend their body temperature; the activation of alternative compensatory mechanisms, such as shivering thermogenesis, could have masked the role of UCP1 on EM. The study of Feldmann et al. (2009) also suggests that the impact of housing temperature on EM has been overlooked by most of the studies on animal models, and that cold stress could have confounded many studies. Humans tend to live at thermoneutrality, with the aid of clothing and heating. Thus, to translate the metabolic studies performed in mice to humans, experiments should be conducted under thermoneutral conditions.

Other evidence also support the role for UCP1 in EM. For example, transgenic mice expressing UCP1 in white fat depots display a lean phenotype (reviewed in Klaus et al., 2012). Moreover, muscle-specific ectopic expression of UCP1 leads to increased energy expenditure, delayed diet-induced obesity development, improved glucose homeostasis, increased insulin stimulated glucose uptake, and increased lipid metabolism (Keipert et al., 2013; Ost et al., 2014). This is in agreement with evidence showing that the selective induction of SkM UCP1-mediated proton-leak leads to an increased whole body energy expenditure as well as decreased adiposity (Adjeitey et al., 2013).

When chronically activated by cold exposure, UCP1 mediated-BAT thermogenesis enhances the oxidation of metabolic substrates necessary for sustaining enhanced thermogenesis. Under these conditions, BAT not only use stored lipids as substrates, but also large quantities of glucose and triglycerides (the last mainly in the form of chylomicrons) from the circulation (Bartelt et al., 2012; Peirce and Vidal-Puig, 2013). Therefore, by decreasing plasma lipids, lowering plasma glucose, and diminishing obesity, BAT has a potential role in protecting against obesity and T2DM.

UCP1 expressing adipocytes are present in adult human

It was previously thought that in humans, BAT disappears rapidly after birth. However, more recently the use of radiodiagnostic techniques [positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT)] together with histological methods has unequivocally identified the presence of UCP1-expressing adipocyte depots in adult humans. The tissue is not present in defined regions, but rather scattered within the WAT (Nedergaard et al., 2007). However, it is currently unclear whether the deposits of UCP1-expressing adipocytes in adult humans are analogous to beige or brown fat.

The enhancement of BAT activity or the browning of WAT in humans has been linked to cold tolerance, enhanced energy expenditure, and protection against metabolic diseases, such as obesity and T2DM (for review Harms and Seale, 2013; Saito, 2013). In fact, the amount of metabolic active BAT in humans positively correlates with RMR and inversely with body mass index (BMI), fat mass (van Marken Lichtenbelt et al., 2009), and the development of T2DM. In addition, it has been shown that genetic variants of UCP1 are associated with fat metabolism, obesity, and diabetes. Among the UCP1 polymorphisms, the A3826G SNP in the promoter region has been associated with obesity, weight gain, and resistance to weight loss (reviewed in Jia et al., 2010).

Uncoupling protein-3 (UCP3)

UCP3 is primarily expressed in skeletal muscle, but it is also found in BAT and heart tissue. Although UCP3 was first discovered and described in 1997 (Boss et al., 1997), the mechanisms of activation as well as its physiological role is still under debate (Cioffi et al., 2009). Due to its close homology with UCP1, UCP3 was initially implicated in thermoregulation (Boss et al., 1997), as it has been demonstrated to uncouple in a number of experimental models. However, other evidence has questioned the uncoupling activity of UCP3, including findings that (i) higher expression of UCP3 is not always associated with increased mitochondrial uncoupling (such as during fasting Cadenas et al., 1999) and (ii) UCP−/−3 mice do not show thermoregulation problems and are not obese (Gong et al., 2000; Vidal-Puig et al., 2000). Indeed, UCP3 mediated-uncoupling (called mild uncoupling) seems to be activated by specific cofactors, with FFA and reactive oxygen species (ROS) playing crucial and interrelated roles (Brand and Esteves, 2005; Lombardi et al., 2008, 2010), being the absence of one on these cofactors able to musk UCP3-mediated uncoupling.

UCP3 is also thought to play key regulatory roles in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and in preventing mitochondrial ROS-induced oxidative damage (Cioffi et al., 2009). Regarding the former, studies relating to the enhancement in SkM UCP3 expression have provided evidence for a close relationship to situations in which there is increased fatty acid oxidation (reviewed in Bezaire et al., 2007; Cioffi et al., 2009). SkM mitochondria isolated from UCP−/−3 mice have a lower ability to oxidize fatty acids than those from UCP+/+3 mice (Costford et al., 2008; Senese et al., 2011), that plausibly is responsible for the greater fat storage observed following long-term high fat feeding in mice lacking UCP3 (Nabben et al., 2011).

UCP3 also plays an important role in protecting cells against oxidative damage (Brand and Esteves, 2005; Goglia and Skulachev, 2003; Nabben et al., 2008; Schrauwen and Hesselink, 2004b). UCP3 may aid in mitigating ROS emission from the ETC; this role seems to be related to UCP3-mediated uncoupling and the consequent reduction in Δp. In fact, Δp is a key factor in influencing mitochondrial O2− release (Korshunov et al., 1997) and a slight reduction in Δp is associated to a significant depression of O2− release. Interestingly, ROS itself or ROS by-products can induce UCP3 uncoupling, which provides a negative feedback loop for mitochondrial ROS production (Brand and Esteves, 2005). The sequential molecular mechanisms underlying ROS induced- and UCP3-mediated uncoupling seems to involve glutathionylation of the protein: a slight increase in ROS production promotes UCP3 de-glutathionylation, which activates UCP3-mediated uncoupling and further decreases ROS emission (Mailloux et al., 2011).

Another hypothesis concerning the role of UCP3 in protecting mitochondria from oxidative damage suggests that UCP3 is involved in the export of LOOH, which accumulates on the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane (MIM), out of the matrix. This mechanism would reduce or eliminate LOOH from the inner leaflet of the MIM, which could otherwise trigger a cascade of oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA and enzymes as well as other critical mitochondrial matrix-localized components (Goglia and Skulachev, 2003). This hypothesis has been validated by studies on mitochondria isolated from UCP+/+3 and UCP−/−3 mice, which underscores the ability of UCP3 to translocate LOOH and mediate LOOH-dependent mitochondrial uncoupling (Lombardi et al., 2010).

Role of UCP3 in energy metabolism

Many studies have demonstrated that mitochondrial functionality is compromised in obesity and T2DM. In skeletal muscle, decreased mitochondrial uncoupling together with impaired mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation lead to fatty acids and/or their metabolites accumulation which, associated to increased oxidative stress, are crucial aspects in the development and progression of the above pathologies (Goodpaster et al., 2001; Patti and Corvera, 2010). Indeed, states of insulin-resistance are characterized by increased LOOH levels in SkM, and patients with T2DM exhibit damaged mitochondria with reduced functional capacity.

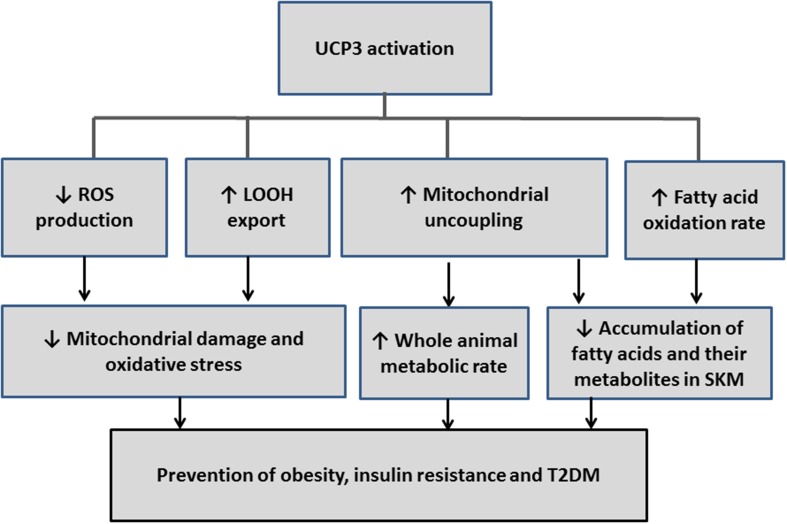

The involvement of UCP3 in mild uncoupling, in protection from ROS- and/or LOOH-induced oxidative stress, and in the amelioration of the fatty acid oxidation rate (see above) suggest a protective role for this protein in obesity and T2DM (Figure 2). This possibility is strengthened by findings that UCP3 is expressed in SkM, which is a tissue that represents 40% of metabolic active mass and largely contributes to energy homeostasis.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram that illustrates how the reactions influenced by UCP3 could be redirected to prevent or treat obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

More experimental evidence supports a role of UCP3 in EM, including the findings that (i) UCP3 transgenic mice are less efficient in metabolism than wild-type controls (Costford et al., 2006) and are protected against high fat diet-induced obesity (Son et al., 2004; Costford et al., 2006); (ii) an enhancement of SkM UCP3 levels (also associated with higher BAT UCP1 levels) has been observed in obesity-resistant mice compared to obesity-prone mice (Fink et al., 2007); and (iii) modest UCP3 overexpression in skeletal muscle mimics physical exercise by increasing spontaneous activity and energy expenditure in mice (Aguer et al., 2013). Conversely, studies performed on UCP−/−3 mice argue against a role for UCP3 in EM, since these mice do not present reduced RMR and are not obese (Vidal-Puig et al., 2000). However, these studies were performed in mice housed at 20–22°C, a condition that, as described above, represents chronic thermal stress [see Uncoupling Protein-1 (UCP1) section]. Therefore, the occurrence of compensatory thermogenic mechanisms in UCP−/−3 mice could have masked the possible role of the protein in EM.

UCP3 also shows a protective role in T2DM. However, when studies were performed on transgenic mice, a clear involvement of the protein was evident when UCP3 overexpressing animals were used as a model (Choi et al., 2007; Costford et al., 2008). Instead, in UCP−/−3 fed a high fat diet regimen (known to induce a state of insulin resistance), insulin sensitivity has been reported to be unaffected (Vidal-Puig et al., 2000), enhanced (Costford et al., 2008), or reduced (Costford et al., 2008; Senese et al., 2011), with the effect being dependent on the age of the mice. Costford et al. (2008). On the other hand, UCP3+/− heterozygous mice show an approximate 50% reduction in SkM UCP3 protein levels when compared to UCP3+/+, and a clear decline in insulin sensitivity has been reported. The effect was observed both when mice were fed with a standard diet or with a high fat diet (Senese et al., 2011). These data are in good accordance with clinical observations reporting that (i) a 50% reduction of UCP3 protein in human SkM is correlated with the incidence of T2DM (Schrauwen et al., 2001); and (ii) in humans, UCP3 protein levels are reduced in the pre-diabetic state of impaired glucose tolerance (Schrauwen and Hesselink, 2004a; Mensink et al., 2007).

Human Polymorphisms in the UCP3 gene also suggest an impact of UCP3 on fat metabolism, obesity, and T2DM. In this context, the UCP3 gene polymorphism –55T allele has been linked to enhanced UCP3 mRNA expression and RM (Schrauwen et al., 1999). Heterozygous C/T is associated with decreased obesity and T2DM risk (Meirhaeghe et al., 2000; Herrmann et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2005). Importantly, these findings have been recently confirmed through a meta-analysis showing an association of the polymorphism with protection from obesity in a European patient population (de Almeida Brondani et al., 2014). The association between the −55CT polymorphism of UCP3 and a lower BMI, however, is modulated by energy intake, since it disappears when caloric intake is increased (Lapice et al., 2014).

Heterozygous individuals that have a missense G304A polymorphism show decreased whole body fat oxidation compared to controls (Argyropoulos et al., 1998). They also present reduced levels of plasma lactate (Adams et al., 2009), that can be plausibly due to an impaired consumption of long chain fatty acids for muscle energy and to a greater reliance upon carbohydrates for energy.

Recently, four novel and heterozygous mutations in the UCP3 gene were identified (V56M, A111V, V192I, and Q252X) (Musa et al., 2012). Children carrying these mutations exhibited a higher percentage of fat and BMI, which was associated with dyslipidemia and lower insulin sensitivity (Musa et al., 2012).

Concluding remarks and perspective

Targeting processes that lead to a reduction in mitochondrial coupling/efficiency and ROS production (thus oxidative stress) could be a promising therapeutic strategy to combat obesity and its co-morbidities (such as T2DM). The uncoupling proteins have several hypothesized functions including thermogenesis in certain tissues, protection from ROS, mediation of fatty acids oxidation and export of fatty acids, which are all related to the above pathologies. Hence, an understanding of the mitochondrial processes that lead to uncoupling and, in particular, the elucidation of the exact role played by UCPs at the mitochondrial level and in EM may provide an attractive therapeutic target for diseases rooted in metabolic imbalance.

In this context, the recruitment of thermogenic brown and/or beige adipocytes through activation of UCP1, and by expanding the tissue, through drugs or other methods, provide a promising approach for enhancing energy expenditure and combating obesity comorbidities. Recent evidence, indicating that brown and beige adipocyte can be recruited by different stimuli, raises the possibility that they may represent separate and distinct targets for therapeutic intervention. Although the roles of UCP3 are not completely clear, current data in human subjects (living at thermoneutrality) suggest a possible involvement of this protein in EM as well as in counteracting obesity, insulin resistance, and T2DM (Figure 2). Therefore, UCP1 and UCP3 represent promising therapeutic targets for treating pathologies that result from energy unbalance.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Adams S. H., Hoppel C. L., Lok K. H., Zhao L., Wong S. W., Minkler P. E., et al. (2009). Plasma acylcarnitine profiles suggestincomplete long-chain fatty acid beta-oxidation and altered tricarboxylic acid cycleactivity in type 2 diabetic African-American women. J. Nutr. 139, 1073–1081. 10.3945/jn.108.103754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjeitey C. N., Mailloux R. J., Dekemp R. A., Harper M. E. (2013). Mitochondrial uncoupling in skeletal muscle by UCP1 augments energy expenditure and glutathione content while mitigating ROS production. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 305, E405–E415. 10.1152/ajpendo.00057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguer C., Fiehn O., Seifert E. L., Bézaire V., Meissen J. K., Daniels A., et al. (2013). Muscle uncoupling protein 3 overexpression mimics endurance training and reduces circulating biomarkers of incomplete β-oxidation. FASEB J. 27, 4213–4225. 10.1096/fj.13-234302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argyropoulos G., Brown A. M., Willi S. M., Zhu J., He Y., Reitman M., et al. (1998). Effects of mutations in the human uncoupling protein 3 gene on the respiratory quotient and fat oxidation in severe obesity and type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 102, 1345–1351. 10.1172/JCI4115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartelt A., Merkel M., Heeren J. (2012). A new powerful player in lipoprotein metabolism: brown adipose tissue. J Mol. Med. (Berl.) 90, 887–893. 10.1007/s00109-012-0858-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezaire V., Seifert E. L., Harper M. E. (2007). Uncoupling protein-3: clues in an ongoing mitochondrial mystery. FASEB J. 21, 312–324. 10.1096/fj.06-6966rev [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss O., Samec S., Dulloo A., Seydoux J., Muzzin P., Giacobino J. P. (1997). Uncoupling protein-3, a new member of the mitochondrialcarrier family with tissue specific expression. FEBS Lett. 408, 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M. D., Esteves T. C. (2005). Physiological functions of the mitochondrial uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3. Cell Metab. 2, 85–93. 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowiecki L., Collet A. J., Follea N., Guay G., Jahjah L. (1982). Brown adipose tissue hyperplasia: a fundamental mechanism of adaptation to cold and hyperphagia. Am. J. Physiol. 242, E353–E359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas S., Buckingham J. A., Samec S., Seydoux J., Din N., Dulloo A. G., et al. (1999). UCP2 and UCP3 rise in starved rat skeletal muscle but mitochondrial proton conductance is unchanged. FEBS Lett. 462, 257–260. 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01540-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon B., Nedergard J. (2004). Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 84, 277–359. 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrière A., Jeanson Y., Berger-Müller S., André M., Chenouard V., Arnaud E., et al. (2014). Browning of white adipose cells by intermediate metabolites: an adaptive mechanism to alleviate redox pressure. Diabetes 63, 3253–3265. 10.2337/db13-1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. S., Fillmore J. J., Kim J. K., Liu Z. X., Kim S., Collier E. F., et al. (2007). Overexpression of uncoupling protein 3 in skeletal muscle protects against fat-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1995–2003. 10.1172/JCI13579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi F., Senese R., de Lange P., Goglia F., Lanni A., Lombardi A. (2009). Uncoupling proteins: a complex journey to function discovery. Biofactors 35, 417–428. 10.1002/biof.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costford S. R., Chaudhry S. N., Crawford S. A., Salkhordeh M., Harper M. E. (2008). Long-term high-fat feedinginduces greater fat storage in mice lacking UCP3. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 295, E1018–E1024. 10.1152/ajpendo.00779.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costford S. R., Chaudhry S. N., Salkhordeh M., Harper M. E. (2006). Effects of the presence, absence, and overexpression of uncoupling protein-3 on adiposity and fuel metabolism in congenic mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 290, E1304–E1312. 10.1152/ajpendo.00401.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Brondani L., de Souza B. M., Assmann T. S., Bouças A. P., Bauer A. C., Canani L. H., et al. (2014). Association of the UCP polymorphisms with susceptibility to obesity: case-control study and meta-analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41, 5053–5067. 10.1007/s11033-014-3371-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divakaruni A. S., Brand M. D. (2011). The regulation and physiology of mitochondrial proton-leak. Physiology 26, 192–205. 10.1152/physiol.00046.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enerback S., Jacobsson A., Simpson E. M., Guerra C., Yamashita H., Harper M. E., et al. (1997). Mice lacking mitochondrial uncoupling protein are cold-sensitive but not obese. Nature 387, 90–94. 10.1038/387090a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann H. M., Golozoubova V., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. (2009). UCP1 Ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 9, 203–209. 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink B. D., Herlein J. A., Almind K., Cinti S., Kahn C. R., Sivitz W. I. (2007). Mitochondrial proton-leak in obesity resistant and obesity-prone mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293, R1773–R1780. 10.1152/ajpregu.00478.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goglia F., Skulachev V. P. (2003). A function for novel uncoupling proteins: antioxidant defense of mitochondrial matrix by translocating fatty acid peroxides from the inner to the outer membrane leaflet. FASEB J. 17, 1585–1591. 10.1096/fj.03-0159hyp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golozoubova V., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. (2006). UCP1 is essential for adaptive adrenergic nonshivering thermogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. 291, E350–E357. 10.1152/ajpendo.00387.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong D. W., Monemdjou S., Gavrilova O., Leon L. R., Marcus-Samuels B., Chou C. J., et al. (2000). Lack of obesity and normal response to fasting and thyroid hormone in mice lacking uncouplingprotein-3. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16251–16257. 10.1074/jbc.M910177199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodpaster B. H., He J., Watkins S., Kelley D. E. (2001). Skeletal muscle lipid content and insulin resistance: evidence for a paradox in endurance-trained athletes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 5755–5761. 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms M., Seale P. (2013). Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat. Med. 19, 1252–1263. 10.1038/nm.3361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper M. E., Green K., Brand M. D. (2008). The efficiency of cellular energy transduction and its implications for obesity. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 28, 13–33. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann S. M., Wang J. G., Staessen J. A., Kertmen E., Schmidt-Petersen K., Zidek W., et al. (2003). Uncoupling protein 1 and 3 polymorphisms are associated with waist-to-hip ratio. J. Mol. Med. 81, 327–332. 10.1007/s00109-003-0431-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J. J., Tian Y. B., Cao Z. H., Tao L. L., Zhang X., Gao S. Z., et al. (2010). The polymorphisms of UCP1 genes associated with fat metabolism, obesity and diabetes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 37, 1513–1522. 10.1007/s11033-009-9550-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keipert S., Ost M., Chadt A., Voigt A., Ayala V., Portero-Otin M., et al. (2013). Skeletal muscle uncoupling-induced longevity in mice is linked to increased substrate metabolism and induction of the endogenous antioxidant defense system. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 304, E495–E506. 10.1152/ajpendo.00518.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus S., Keipert S., Rossmeisl M., Kopecky J. (2012). Augmenting energy expenditure by mitochondrial uncoupling: a role of AMP-activated protein kinase. Genes Nutr. 7, 369–386. 10.1007/s12263-011-0260-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg M., Echtay K. S. (2001). Uncoupling proteins: the issues from a biochemist point of view. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1504, 128–143. 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00242-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korshunov S. S., Skulachev V. P., Starkov A. A. (1997). High protonic potential actuates a mechanism of production of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 416, 15–18. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01159-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss S., Zhang C. Y., Lowell B. B. (2005). The mitochondrial uncoupling-protein homologues. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 248–261. 10.1038/nrm1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapice E., Monticelli A., Cocozza S., Pinelli M., Giacco A., Rivellese A. A., et al. (2014). The energy intake modulates the association of the -55CT polymorphism of UCP3 with body weight in type 2 diabetic patients. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 38, 873–877. 10.1038/ijo.2013.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. J., Liu P. Y., Long J., Lu Y., Elze L., Recker R. R., et al. (2005). Linkage and association analyses of the UCP3 gene with obesity phenotypes in Caucasian families. Physiol. Genomics 22, 197–203. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00031.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi A., Busiello R. A., Napolitano L., Cioffi F., Moreno M., de Lange P., et al. (2010). UCP3 Translocates lipid hydroperoxide and mediates lipid hydroperoxide-dependent mitochondrial uncoupling. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 16599–16605. 10.1074/jbc.M110.102699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi A., Grasso P., Moreno M., de Lange P., Silvestri E., Lanni A., et al. (2008). Interrelated influence of superoxides and free fatty acids over mitochondrial uncoupling in skeletal muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 826–833. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailloux R. J., Seifert E. L., Bouillaud F., Aguer C., Collins S., Harper M. E. (2011). Glutathionylation acts as a control switch for uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21865–21875. 10.1074/jbc.M111.240242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meirhaeghe A., Amouyel P., Helbecque N., Cottel D., Otabe S., Froguel P., et al. (2000). An uncoupling protein 3 gene polymorphism associated with a lower risk of developing Type II diabetes and with atherogenic lipid profile in a French cohort. Diabetologia 43, 1424–1428. 10.1007/s001250051549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensink M., Hesselink M. K., Borghouts L. B., Keizer H., Moonen-Kornips E., Schaart G., et al. (2007). Skeletal muscle uncoupling protein-3 restores upon intervention in the prediabetic and diabetic state: implications for diabetes pathogenesis? Diabetes Obes. Metab. 9, 594–596. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musa C. V., Mancini A., Alfieri A., Labruna G., Valerio G., Franzese A., et al. (2012). Four novel UCP3 gene variants associated with childhood obesity: effect on fatty acid oxidation and on prevention of triglyceride storage. Int. J. Obes. 36, 207–217. 10.1038/ijo.2011.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabben M., Hoeks J., Briede J. J., Glatz J. F., Moonen-Kornips E., Hesselink M. K., et al. (2008). The effect of UCP3 overexpression on mitochondrial ROS production in skeletal muscle of young versus aged mice. FEBS Lett. 582, 4147–4152. 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabben M., Hoeks J., Moonen-Kornips E., van Beurden D., Briedé J. J., Hesselink M. K., et al. (2011). Significance of uncoupling protein 3 in mitochondrial function upon mid- and long-term dietary high-fat exposure. FEBS Lett. 585, 4010–4017. 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard J., Bengtsson T., Cannon B. (2007). Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 293, E444–E452. 10.1152/ajpendo.00691.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ost M., Werner F., Dokas J., Klaus S., Voigt A. (2014). Activation of AMPKα2 is not crucial for mitochondrial uncoupling-induced metabolic effects but required to maintain skeletal muscle integrity. PLoS ONE 9:e94689 10.1371/journal.pone.0094689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patti M. E., Corvera S. (2010). The role of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 31, 364–395. 10.1210/er.2009-0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce V., Vidal-Puig A. (2013). Regulation of glucose homoeostasis by brown adipose tissue. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 1, 353–360. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70055-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic N., Walden T. B., Shabalina I. G., Timmons J. A., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. (2010). Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7153–7164. 10.1074/jbc.M109.053942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter R. K. (2008). Uncoupling protein 1: a short-circuit in the chemiosmotic process. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40, 457–461. 10.1007/s10863-008-9172-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe D. F., Brand M. D. (1996). Contribution of mitochondrial proton leak to skeletal muscle respiration and to standard metabolic rate. Am. J. Physiol. 271, C1380–C1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M. (2013). Brown adipose tissue as a therapeutic target for human obesity. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 7, e432–e438. 10.1016/j.orcp.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrauwen P., Hesselink M. K. (2004b). The role of uncoupling protein3 in fatty acid metabolism: protection against lipotoxicity? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 63, 287–292. 10.1079/PNS2004336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrauwen P., Hesselink M. K. C. (2004a). Oxidative capacity, lipotoxicity, and mitochondrial damage in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53, 1412–1417. 10.2337/diabetes.53.6.1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrauwen P., Hesselink M. K. C., Blaak E. E., Borghouts L. B., Schaart G., Saris W. H., et al. (2001). Uncoupling protein 3 content is decreased in skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 50, 2870–2873. 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrauwen P., Xia J., Walder K., Snitker S., Ravussin E. (1999). A novel polymorphism in the proximal UCP3 promoter region: effect on skeletal muscle UCP3mRNA expression and obesity in male non-diabetic Pima Indians. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 23, 1242–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senese R., Valli V., Moreno M., Lombardi A., Busiello R. A., Cioffi F. (2011). Uncoupling protein 3 expression levels influence insulin sensitivity, fatty acid oxidation, and related signaling pathways. Pflugers Arch. 461, 153–164. 10.1007/s00424-010-0892-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalina I. G., Petrovic N., de Jong J. M. A., Kalinovich A. V., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. (2013). UCP1 in brite/beige adipose tissue mitochondria is functionally thermogenic. Cell Rep. 5, 1196–1203. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son C., Hosoda K., Ishihara K., Bevilacqua L., Masuzaki H., Fushiki T., et al. (2004). Reduction of diet-induced obesity in transgenic mice overexpressing uncoupling protein 3 in skeletal muscle. Diabetologia 47, 47–54. 10.1007/s00125-003-1272-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marken Lichtenbelt W. D., Vanhommerig J. W., Smulders N. M., Drossaerts J. M., Kemerink G. J., Bouvy N. D., et al. (2009). Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1500–1508. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Puig A. J., Grujic D., Zhang C. Y., Hagen T., Boss O., Ido Y., et al. (2000). Energy metabolism in uncoupling protein 3 gene knockout mice. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16258–16266. 10.1074/jbc.M910179199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali A., Murano I., Zingaretti M. C., Frontini A., Ricquier D., Cinti S. (2012). The adipose organ of obesity-prone C57BL/6J mice is composed of mixed white and brown adipocytes. J. Lipid Res. 53, 619–629. 10.1194/jlr.M018846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Boström P., Sparks L. M., Ye L., Choi J. H., Giang A. H., et al. (2012). Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell 150, 366–376. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Cohen P., Spiegelman B. M. (2013). Adaptive thermogenesis in adipocytes: is beige the new brown? Genes Dev. 27, 234–250. 10.1101/gad.211649.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]