Abstract

In response to the questioning of Health Policy and Management (HPAM) by colleagues on the role of rank and file family physicians in the same journal, the author, a family physician in Belgium, is trying to highlight the complexity and depth of the work of his colleagues and their contribution to the understanding of the organization and economy of healthcare. It addresses, in particular, the management of health elements throughout the ongoing relationship of the family doctor with his/her patients. It shows how the three dimensions of prevention, clearly included in the daily work, are complemented with the fourth dimension, quaternary prevention or prevention of medicine itself, whose understanding could help to control the economic and human costs of healthcare.

Keywords: Physicians, Family, Preventive Medicine, Physician’s Role, Medicalization, Ethics, Clinical

From Health Policy and Management (HPAM) eyes, family doctors are rank and file healthcare providers. In a recent paper in this journal, Chinitz and Rodwin (1) express;

“Healthcare delivery organizations are often designed without sufficient participation from the rank and file, especially physicians” and “neglect the complex internal workings of healthcare systems, about which rank and file physicians and nurses are the most knowledgeable”.

And indeed family doctors, viewed as “rank-and-file soldiers” by Chinitz and Rodwin are often ignored and their world is unknown. Let’s see how they can contribute to the understanding of the seminal act in healthcare; the meeting between a patient and a provider.

We are not addressing here the innumerous contributions of family doctors to epidemiology of the first line (2–5), nor their contribution to the health information process (6,7), but their relation to time, to knowledge, and to preventative attitude.

Towards patient-doctor relationship-based care

Following the prevention model of Leavell and Clark (8), which was an explanatory model of the natural history of disease, healthcare systems are engaged in a struggle against disease. A paradigm shift from time and struggle based perspective to a constructivist time and relationship-based preventive pattern of care (9) offers new insight into the practice of doctors, and brings into light the concept of quaternary prevention (10,11), a critical look at medical activities with an emphasis on the need not to harm.

The consultation, meeting between two human beings, is also a meeting between knowledge and feelings or between science and conscience and could induce a considerable range of products and derived costs, from zero expenditure to the most implausible ones.

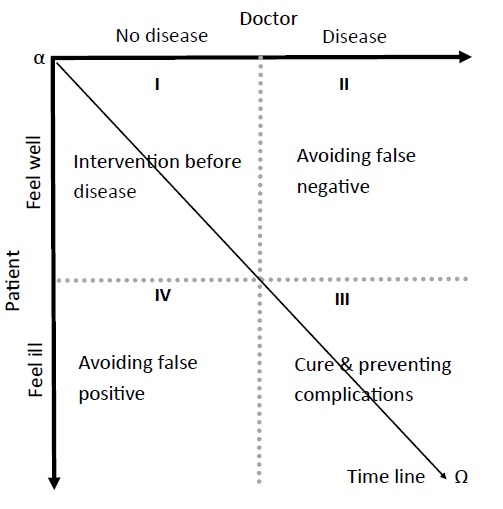

The doctor’s knowledge, true or false, cross the thoughts, true or false, of the patient. By his/her training, the doctor drags irresistibly the patient towards the disease. The patient is ineluctably and by life itself, drawn towards the uncertain and frozen territories of the illness and death. Parodying the Chi² we can establish four fields which represent four different medical action areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Four fields of the patient-doctor encounter based on relationships. The doctor looks for diseases. The patient could feel ill. Timeline is obliquely oriented from left to right, from alpha to omega, from birth to death. Anyone will become sick and die, doctors as well as patients (9).

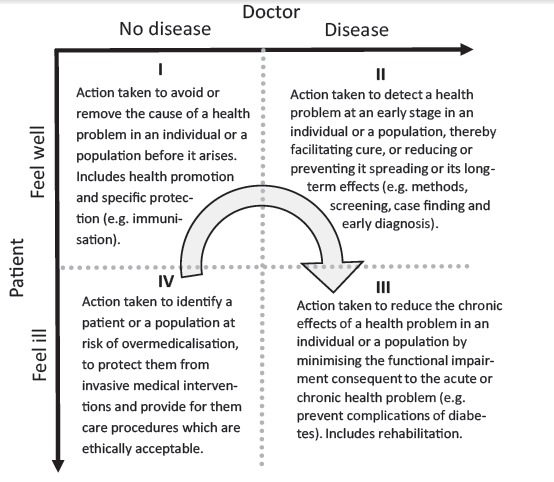

The usual chronological way addresses prevention as a continuous variable. The new constructivist way presents the stage of prevention as discrete variable. The shift from time/disease-based prevention towards a time/relationship-based prevention offers also new perspectives into a physician’s work. By introducing a fourth position, this shift forces the doctor to have a critical look at his/her own activity and influence as potentially harmful for the patient and to question the ethical limits of his/her activities. Quaternary prevention, also known as P4, is then a new term for an old concept: first, do not harm (Figure 2). Alternatively, the four definitions of prevention (12) offer a structured way to discuss four kinds of actions of family doctors.

Figure 2 .

The patient-doctor relationship is at the origin of the four types of activities. The arrow shows that the P4 attitude is impacting all the activity (10,12).

Quaternary prevention concept expanding worldwide

The P4 concept is now widely recognized1. The quaternary prevention movement encompasses the current international movement against overmedicalization and has been endorsed by family doctors in South America (13–15), Europe (16–18), and Asia (19,20).

The enthusiasm generated around this topic shows the P4 concept used as a framework for a multifaceted repositioning of current questions and limitations of medical practice: disease invention (21), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) market extension (22), transformation of symptoms into disease (23), osteoporosis marketing, doubt in breast cancer mass screening (24) and HPV immunization (25), drug marketing (26) as well as empathy and communication, the value of the symptoms, rational use of drug use in mental health, hypertension or dyslipidaemia or incidentaloma (27). And this list is not exhaustive (28). Quaternary prevention involves the need for close monitoring by the doctor himself, a sort of permanent quality control on behalf of the consciousness of the harm they could, even intentionally, do to their patients (29). Quaternary prevention is about understanding that medicine is based on a relationship, and that this relation must remain truly therapeutic by respecting the autonomy of patients and doctors (30). P4 attitude acts as a resistance, a rallying cry against the lack of humanity of whole sectors of medicine and their institutional corruption (31–33).

The task of the family doctor includes naturally the four fields

Caring and understanding patient’s world is still the first duty of the family doctors. Unfortunately the next duty is now to protect patients against medicine. Skipping the word prevention from the table, transforms it in a family doctor basic job description. The four actions are in reality all the daily activities of a family doctor. Family doctors are used to address multiple problems during an encounter (34). As continuity and longitudinality are foundational for family practice, prevention is naturally embedded in daily contacts.

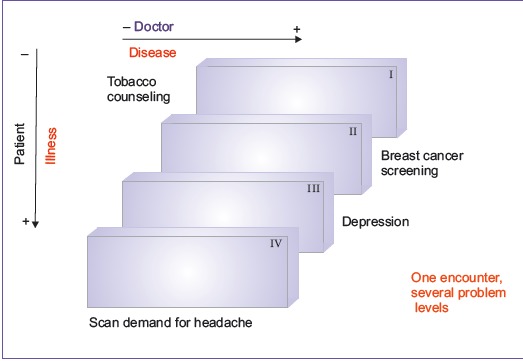

Let’s follow this example: follow-up for a diabetic patient is a common task which is included in the third case, avoiding complications. But the doctors can ask the woman if she has already done her breast mammogram this year, a typically second field task while stop smoking counsel is a first field task. It is not rare that at the end of the encounter the patient asks for something unexpected like demanding a scan for her headache because she has heard about a cousin with headache and head tumour which is typically a fourth field task (Figure 3).

Figure 3 .

The patient-doctor encounter could encompasses problems in each field.

Towards shared decision-making

It is the duty of the family doctors to follow Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) (35). It is also their duty to follow ethically-based medicine (36). Non-smoking recommendation (37) is EBM-based, mammogram is doubtful (38), diabetes follow-up is questioned (39) and head scan for headache is a low likelihood (40). But how will react the family doctor faced with questionable demands? Meeting the demand of patient is the easiest way to shorten the encounter but brings possible human and financial costs induced by false positive results, by overdiagnosis or more generally by overmedicalization. The difficult choice is to explain the doubt of the mammogram and the danger of irradiation. It is also difficult to explain the uncertainty of the results of a scan by using the time consuming shared decision-making process (41) to persuade the patient not go to further examinations.

“Not to do” is not as easy as accepting “to do” (42,43). Doing further examinations and using defensive medicine approach will meet the anxiety of the patient and the anxiety of the doctor. A counsel of “not to do” needs trust between patient and doctor in supporting doubt. Are the health management policies ready to support patient and doctors to fight against overmedicalization and to face anxiety of uncertainty?

The distribution of preventative activities are now firmly established on a new model, privileging the patient-doctor relationships and introducing a cybernetic thinking on the healthcare activities with a special commitment to ethics (44) and positive duty of beneficence (45). P4 attitude acts as a response of family doctor facing overmedicalization, as a resistance, a rallying cry against the lack of humanity of large sectors of medicine.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author is practicing family medicine in the same street with same families since 40 years. He is member of the Wonca International Classification Committee and PhD applicant at Department of General Practice, Liege University. He has very high level of intellectual competing interests but none of other nature.

Author’s contribution

MJ is the single author of the manuscript.

Endnote

1. The P4 network is supported by the Wonca International Classification Committee website under the Quaternary Prevention rubric (http://www.ph3c.org/P4 )

Citation: Jamoulle M. Quaternary prevention, an answer of family doctors to overmedicalization. Int J Health Policy Manag 2015; 4: 61–64. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.24

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO traditional medicine Chinitz DP, Rodwin VG On Health Policy and Management (HPAM): mind the theory-policy-practice gap. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:3613. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison C, Britt H, Miller G, Henderson J. Prevalence of chronic conditions in Australia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gijsen R, Poos R. Using registries in general practice to estimate countrywide morbidity in the Netherlands. Public Health. 2006;120:923–36. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lykkegaard J, Larsen PV, Paulsen MS, Søndergaard J. General practitioners’ home visit tendency and readmission-free survival after COPD hospitalisation: a Danish nationwide cohort study. NPJ Prim care Respir Med. 2014;24:14100. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laux G, Kuehlein T, Rosemann T, Szecsenyi J. Co- and multimorbidity patterns in primary care based on episodes of care: results from the German CONTENT project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamberts H, Meads S, Wood M. Classification of reasons why persons seek primary care: pilot study of a new system. Public Heal Rep. 1984;99:597–605. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soler JK, Okkes I, Wood M, Lamberts H. The coming of age of ICPC: celebrating the 21st birthday of the International Classification of Primary Care. Fam Pract. 2008;25:312–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leavell H, Clark E. Preventive Medicine for the Doctor in His Community an Epidemiologic Approach. McGraw-Hill; 1958.

- 9. Jamoulle M. Information et informatisation en médecine générale [Computer and computerisation in general practice]. Dans: Les informa-g-iciens. Namur, Belgium: Press Univ Namur; 1986. p. 193–209. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/2268/170822.

- 10. Jamoulle M, Roland M. Quaternary prevention. WICC annual workshop: Hongkong, Wonca congress proceedings; 1995. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/2268/173994.

- 11.Jamoulle M. The four duties of family doctors: quaternary prevention - first, do no harm. Hong Kong Pract. 2014;36:72–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bentzen N. Wonca Dictionary of General/Family Practice. Maanedsskr: Copenhagen; 2003.

- 13.Norman AH, Tesser CD. [Quaternary prevention in primary care: a necessity for the Brazilian Unified National Health System] Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:2012–20. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2009000900015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vito EL. Prevención cuaternaria, un término aún no incluido entre los MESH Med (Buenos Aires) Fundación Revista Medicina (Buenos Aires) 2013;73:187–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva AL, Mangin D, Pizzanelli M, Jamoulle M, Wagner HL, Silva DH. et al. Manifesto de Curitiba: pela Prevenção Quaternária e por uma Medicina sem conflitos de interesse. Rev Bras Med Família e Comunidade. 2014;9:371–4. [in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuehlein T, Sghedoni D, Visentin G, Gérvas J, Jamoulle M. Quaternary prevention: a task of the general practitioner. Prim Care [Internet]. 2010. Available from: http://www.primary-care.ch/docs/primarycare/archiv/de/2010/2010-18/2010-18-368_ELPS_engl.pdf.

- 17. Jamoulle M, Tsoi G, Heath I, Mangin D, Pezeshki M, Pizzanelli Báez M. Quaternary prevention, addressing the limits of medical practice. Wonca world conference Prague; 2013. Available from: http://www.ph3c.org/PH3C/docs/27/000322/0000469.pdf.

- 18. Martin C, Heleno B, Hestbech M, Brodersen J. Screening Evidence And Wishful Thinking – A Europrev Workshop About Quaternary Prevention In General Practice. WONCA Europe Conference 2014, Lisbon, Portugal; 2014. Available from: http://www.woncaeurope.org/content/ws407-screening-evidence-and-wishful-thinking-%E2%80%93-europrev-workshop-about-quaternary.

- 19. Jamoulle M, Roland M. Quaternary prevention. From Wonca world Hong Kong 1995 to Wonca world Prague 2013. In Wonca world conference Prague 2013 [Poster]. Available also in Chinese, Thai, Vietnamese, French, Spanish and Portuguese on http://www.ph3c.org/P4.

- 20.Tsoi G. Quaternary prevention. Hong Kong Pract. 2014;36:49–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso-Coello P, García-Franco AL, Guyatt G, Moynihan R. Drugs for pre-osteoporosis: prevention or disease mongering? BMJ. 2008;336:126–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39435.656250.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conrad P, Bergey MR. The impending globalization of ADHD: Notes on the expansion and growth of a medicalized disorder. Soc Sci Med. 2014;122:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering. BMJ. 2002;324:886–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD001877. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomljenovic L, Shaw CA. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine policy and evidence-based medicine: are they at odds? Ann Med. 2013;45:182–93. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.645353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolinsky H. Disease mongering and drug marketing Does the pharmaceutical industry manufacture diseases as well as drugs? EMBO Rep. 2005;6P:612–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mariño Maria A. Incidentaloma. Rev Bras Med Família e Comunidade 2015; forthcoming.

- 28. Welch HG. Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. Boston, MA : Beacon Press; 2012.

- 29.Heath I. Combating Disease Mongering: Daunting but Nonetheless Essential. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuehlein T, Sghedoni D, Visentin G, Gérvas J, Jamoulle M. Quaternary prevention: a task of the general practitioner. Prim Care [internet]. 2010. Available from: http://www.primary-care.ch/pdf_f/2010/2010-18/2010-18-368_ELPS_engl.pdf.

- 31.Light DW, Lexchin J, Darrow JJ. Institutional Corruption of Pharmaceuticals and the Myth of Safe and Effective Drugs. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;14:590–600. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodwin MA. Institutional Corruption & Pharmaceutical Policy. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41:544–52. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gotzsche PG. Deadly Medicines and Organised Crime: How Big Pharma Has Corrupted Healthcare. London: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 2013.

- 34.Mangin D, Heath I, Jamoulle M. Beyond diagnosis: rising to the multimorbidity challenge. Br Med J. 2012;344:e3526. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giguere A, Labrecque M, Haynes R, Grad R, Pluye P, Légaré F. et al. Evidence summaries (decision boxes) to prepare clinicians for shared decision-making with patients: a mixed methods implementation study. Implement Sci. 2014;9:144. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Feldman AM. Understanding Health Care Reform: Bridging the Gap Between Myth and Reality. New York, NY: CRC Press; 2011.

- 37.Lancaster T, Stead L, Silagy C, Sowden A. Effectiveness of interventions to help people stop smoking: findings from the Cochrane Library. BMJ. 2000;321:355–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welch HG, Passow HJ. Quantifying the benefits and harms of screening mammography. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:448–54. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Miao Y, Shah ND, Lee SJ, Steinman MA. Potential Overtreatment of Diabetes Mellitus in Older Adults With Tight Glycemic Control. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Nabhani K, Kakaria A, Syed R. Computed tomography in management of patients with non-localizing headache. Oman Med J. 2014;29:28–31. doi: 10.5001/omj.2014.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Légaré F, Ratté S, Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Gravel K, Graham ID. et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD006732. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Widmer D, Herzig L, Jamoulle M. [Quaternary prevention: is acting always justified in family medicine?] Rev Med Suisse. 2014;10:1052–6. [in French]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heath I. The art of doing nothing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2012;18:242–6. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2012.733691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Báez EM. Princípios Éticos e Prevenção Quaternária: é possível não proteger o exercício do princípio da autonomia? [Ethical Principles and Quaternary Prevention: is it possible not to protect the exercise of the principle of autonomy?] Rev Bras Med Família e Comunidade 2013; 9: 169-73. [in Portuguese].

- 45.Sharpe VA. Why “Do No Harm”? The Influence of Edmund D Pellegrino’s Philosophy of Medicine. Theor Med. 1997;18:197–215. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-3364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]