Abstract

Background: Health insurance has been acknowledged by researchers as a valuable tool in health financing. In spite of its significance, a subscription paralysis has been observed in India for this product. People who can afford health insurance are also found to be either ignorant or aversive towards it. This study is designed to investigate into the socio-economic factors, individuals’ health insurance product perception and individuals’ personality traits for unbundling the paradox which inhibits people from subscribing to health insurance plans.

Methods: This survey was conducted in the region of Lucknow. An online questionnaire was sent to sampled respondents. Response evinced by 263 respondents was formed as a part of study for the further data analysis. For assessing the relationships between variables T-test and F-test were applied as a part of quantitative measuring tool. Finally, logistic regression technique was used to estimate the factors that influence respondents’ decision to purchase health insurance.

Results: Age, dependent family members, medical expenditure, health status and individual’s product perception were found to be significantly associated with health insurance subscription in the region. Personality traits have also showed a positive relationship with respondent’s insurance status.

Conclusion: We found in our study that socio-economic factors, individuals’ product perception and personality traits induces health insurance policy subscription in the region.

Keywords: Health Insurance Perception, Mediclaim Policy, Personality Traits, Private Voluntary Health Insurance (PVHI)

Background

Over two-third of the Indian populace do not possess any form of health insurance cover. Of the 320 million Indians who are covered, 2.9 million are enrolled under the Private Voluntary Health Insurance (PVHI)1 plans, 63 million through Employee State Insurance Scheme (ESIS) and Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS) and the remainder 254 million people are covered through other government managed social health insurance schemes and community-based schemes (1). Despite the fact, health insurance forms a vital component of health financing in most part of the world, in India it has been found quiescent (2).

The total healthcare expenditure in India accounts for a 6% to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of which 66.9% of its composition consists of Out-of-Pocket (OOP) payments according to the World Health Organization (WHO) report (3). This disposition has compelled a need to formulate an organized set of health financing mechanism to which health insurance acts as a pertinent option.

India’s tremendous population growth in the past decade has necessitated the need for a quality and affordable healthcare market. Consequently, a notable upsurge in the cost of medical care has taxed the pockets of the people enormously (4). In India, no mandatory provision prevails for subscribing to the health insurance plans, therefore inducing people to live on a very volatile and risky healthcare seeking environment. But the biggest worry sprang up for the people belonging to lower- and middle-income groups2inhabiting in the country (5). Since most of the Government Sponsored Health Insurance Schemes (GSHIS) which are currently operational in India, largely concentrate and focuses on covering people belonging to below the poverty levels. Concurrently, people residing Above the Poverty Levels (APL) potentially remain outside the ambit of these GSHIS thus left with only option of choosing PVHI plans offered and managed by the public and private insurance companies in the market (6).

A report published by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) showed a decadal rise in the level of per capita personal disposable income from the year 2004 to 2012 (7). In addition, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has also reported a slender rise in the household savings rates over a decade (8). Irrespective of these facts, the participation of people belonging to varied income groups2 has been unseemly poor towards the health insurance. Moreover, those sought to possess a health insurance predominantly got the coverage either from their employer or some other related sources instead purchasing privately from the insurance companies.

Against this backdrop, a further need was generated to investigate into the factors which recedes an individual to purchase PVHI plans. For the purpose, this paper uses quantitative methodological approach to assess and compare the insured and uninsured individuals on the basis of their socio-economic background, perceptions regarding the health insurance product, and individual personality traits. For tests purposes, a hypothesis was framed as: Socio-economic, product perception and individual personality traits have a significant association with the individual’s insurance status.

Overview of Private Voluntary Health Insurance (PVHI)

In the Indian market, health insurance policies are popularly offered by life and non-life insurance companies and are commonly referred to as ‘mediclaim policies’. The PVHI plans were initially launched by public non-life insurance companies in the year 1986. Later in 2001, a regulation was passed which approved the entry of private non-life insurance companies to venture into the health insurance business in India (9). Currently there are 28 non-life insurance company operating in India and of them 23 transacts health insurance business. The health insurance products offered by transacting insurance companies shares common policy wordings but differ in their plans design, features and coverage’s. In fact, parallel to the traditional claim settlement procedure, direct cashless settlements of claims are also provided to the customers’ in the empanelled hospitals by the insurance companies for the health claims (10,11).

Health insurance in Lucknow region

In conformity to other regional areas in India, Lucknow region shares a similar setting in the health insurance. There is no mandatory or universal health insurance scheme for all the citizens in the region. In this region, 337,416 beneficiaries were covered by the Employees State Insurance Scheme (ESIS) in 2011–2. On the other hand 75,488 families belonging to below poverty level were only covered by Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yogna (RSBY) of the target 153,639 families during 2013–4. Due to non-availability of data regarding PVHI coverage for the city it became hard to express the status quo. But looking at the state level coverage figures, one could easily discern that a huge deficit might even exist in the region (see Table 1). Since the government funded and operated health insurance schemes have defined norms and criterions for the purpose of enrollment hence leaves large proportion of the population in the region out of its ambit of coverage. Therefore, people are left with an option of PVHI in the region. Despite the presence of several insurers’ in the region the subscription and the coverage for PVHI have been paltry.

Table 1 . Business volume and number of beneficiaries figures for private voluntary health insurance plans in India .

| State |

Gross written premium

(2012–3)* |

% share |

Number of policies issued

(2012-3) |

Number of

beneficiaries |

Population 2011

(census) |

| Maharashtra | 44,916,597,670 | 29.62 | 4,306,735 | 20,672,328 | 112,374,333 |

| Tamil Nadu | 17,825,672,282 | 11.76 | 1,722,694 | 8,268,931 | 72,147,030 |

| Delhi | 16,200,391,355 | 10.68 | 1,579,136 | 7,579,853 | 16,787,941 |

| Karnataka | 13,914,374,185 | 9.18 | 1,363,799 | 6,546,235 | 61,095,297 |

| West Bengal | 10,047,007,232 | 6.63 | 1,004,904 | 4,823,539 | 91,276,115 |

| Gujarat | 8,944,249,149 | 5.90 | 861,347 | 4,134,466 | 60,439,692 |

| Haryana | 7,477,472,123 | 4.93 | 717,789 | 3,445,387 | 25,351,462 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 6,909,153,225 | 4.56 | 646,010 | 3,100,848 | 84,580,777 |

| Kerala | 6,024,207,164 | 3.97 | 574,231 | 2,756,308 | 33,406,061 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 5,325,035,079 | 3.51 | 516,808 | 2,480,678 | 199,812,341 |

Source-Authors creation; Number of beneficiaries is authors approximation, calculated by considering all the policy as ‘family policy’ with average household size (as per census 2011).

*Figure includes group and non-group health insurance premium and policies.

Theoretical framework

A theoretical framework was designed to examine the effect of socio-economic factors, product perception and individual’s personality traits have on the health insurance plan uptake. Three models were framed for estimation purpose and to also observe their association with the insurance status.

Past studies have showed the positive association of socio-economic variables with the individuals intention to purchase health insurance (12–14). Several empirical studies cited education, income, family size, dependents and health status as variables which were significantly associated with health insurance purchase (15–21). Therefore, these variables were considered and grouped together while preparing a theoretical framework.

Taking cue from the past studies which demonstrated the effects of price, services, product quality, product information, brand image, perceived risk and product satisfaction on the customer purchase/re-purchase intention, therefore few attributes were included in the study to ascertain their influence on the health insurance plan purchase (22–27).

Myriads of research work have gone on to capture the effect of personality traits have on consumer buying process but in general they examined the commodities of tangible nature (28–30). Whereas no studies were found which exhibited any linkages between personality traits and health insurance product subscription. In cognisance with the established research works and considering the normal good characterstic of the health insurance product, it was ideated that a similar consumption pattern might as well exists among the people for this product.

Since consumer behaviour rests upon indiviuals personal charactertics (i.e. dipositional factors), Macadams suggested a three-tired framework to study the personality psychology in terms of personality traits, personal concerns and life stories (31,32). Taking a cue from his work, a shorter five item scale version was constructed only to gather responses on the indiviual personality traits. The items included in the interview schedule were designed according to the requirements of the study. Lastly, a positive association was hypothesized in relation to this factor with the insurance status.

Methods

Study setting, design, variables and data collection

The study was conducted through an online survey in the region of Lucknow. The electronic mail address of 5,000 customers in the region who invest in the financial products like life insurance, mutual funds and term deposits was procured from an independent private database management agency. An online questionnaire was sent to the customers on their electronic mail addresses those domiciled within the geographical boundaries of the study. The complete survey activity was conducted between November 2013 and April 2014 and only responses received during these months were chosen for the study purpose.

From the total sampled base, only 307 online responses were received which formed approximately a 6% response rate. Of the total received responses, only 263 were found to be complete and appropriate to perform further analysis. Information on respondent age, gender, occupation, marital status, education, dependents, household expenditure, medical expenditure, income and health status were gathered along with inputs on personality traits and product perception through a structured questionnaire. A five point likert scale ranging from ‘1= strongly disagree’ to ‘5= strongly agree’ was used for encapsulating respondents opinions and views over various qualitative attributes.

Lastly, information on respondent’s health insurance status was also noted. A criterion was set for this as – ‘insured’ those who presently bought a health insurance cover and ‘uninsured’ – those who have not bought a health insurance cover or may have earlier bought but not renewed it.

Statistical analysis

Two distinct statistical techniques were used in the study. In the first step, to ascertain the relationship of socio-economic, product perception and individual personality traits with insured status (insured and uninsured), χ2 test and F-test were used. Then variables under each main factor heads which shares a significant association with the insured status (at P≤ 0.01 to P≤ 0.10) were chosen for the final logit regression analysis.

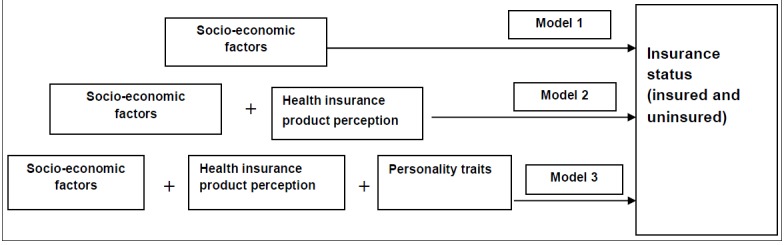

In the second step, a binary logistic regression analysis technique was applied for assessing the impact the independent variables places over the dependent variable i.e. the insured status for each respondent. For estimation purpose, three modeled groups were formulated to measure independent effects each of them have on the insurance status (Figure 1). The model is described as follows:

Figure 1 .

Conceptual model

Model 1: Included the socio-economic factors;

Model 2: Included socio-economic variable and product perception variables;

Model 3: Includes socio-economic, product perception and personality traits variables.

The logistic regression equation for estimating each model is mentioned as:

Logit (p i ) = α + β 1 X 1 + β 2 X 2 + β 3 X 3 …………. β n X n

In this equation, pi denotes the probability for the ith respondent which equals to 1 if insured and 0 if otherwise i.e. uninsured. α is the intercept term, Xn represents the explanatory variable 1 to n in the study under each model, and βn is the coefficient for the explanatory variables. A positive value of β reflects the more likelihood of dependent variable to one and vice versa. The analyses were performed using the statistical software SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Descriptive summary

The sampled respondents were found in their middle ages with an average age of 39.60 years (Table 2). The majority of the respondents’ were found to be male (88.70%). Fifty six percent of the sampled respondents have a family size between 3-4 members. A notable 85% of the sampled respondents were married. Eighty percent of the respondent have attained postgraduate degrees with 68% belong to a salaried group. A sizeable 57% of the respondents have an annual income over >5 lacs (Indian Rupees). Thirty eight percent of the respondents in aggregate have reported on their health status as poor and very poor. The monthly medical expenditure for 61% of the sampled respondent was slated under Rs 5,000.

Table 2 . Descriptive characteristics at individual level for socio-economic factors .

| Summary | Mean/percentage |

| Number of respondents | 263 |

| Age (years) | 39.57 |

| Gender | |

| Male (%) | 88.70 |

| Female (%) | 11.30 |

| Marital status | |

| Single (%) | 15.00 |

| Married (%) | 85.00 |

| Household member (%) | |

| 1–2 | 16.90 |

| 3–4 | 56.00 |

| 5–6 | 24.10 |

| >6 | 3.00 |

| Dependent members (%) | |

| <4 | 92.90 |

| >4 | 7.10 |

| Education (%) | |

| Graduate | 20.30 |

| Postgraduate | 79.70 |

| Occupation (%) | |

| Salaried | 67.70 |

| Self-employed | 32.30 |

| Incomeab (%) | |

| 1 Lac–3 Lac | 6.00 |

| 3 Lac–5 Lac | 37.20 |

| >5 Lac | 56.80 |

| Medical expenditurebc (%) | |

| <5000 | 60.50 |

| 5001–10000 | 22.60 |

| >10000 | 16.90 |

| Health status (%) | |

| Good | 22.60 |

| Fair | 39.50 |

| Poor | 25.20 |

| Very poor | 12.80 |

aAnnual figure; bIndian Rupees; cMonthly figure

Relationship between socio-economic factors, individual’s personality traits and product perception with insurance status

As shown by Table 3, age, marital status, number of dependents, education, medical expenditure and health status had a significant association with insurance status. Mean age of the uninsured (M= 45.69) was found notably higher than the mean age of the insured (M= 35.76). Among male respondents 61% have purchased a health insurance cover while 39% remained without a health insurance cover. However the relationship between gender and insurance status was found to be non-significant (P= 0.98) in the study. While a noteworthy association had been witnessed between the respondents marital status and insurance status (P= 0.00).

Table 3 . Socio-economic factors and insurance status .

| Variable | Insurance status | P | |

| Insured | Uninsured | ||

| Age (years) (mean) | 35.76 | 45.69 | 0.00 |

| Gender | 0.98 | ||

| Male | 143 (60.85) | 92 (39.15) | |

| Female | 17 (60.71) | 11 (39.29) | |

| Marital status | 0.00 | ||

| Single | 33 (84.62) | 6 (15.38) | |

| Married | 127 (56.69) | 97 (43.31) | |

| Household members | 0.29 | ||

| 1–2 | 39 (86.67) | 6 (13.33) | |

| 2–4 | 85 (57.43) | 63 (42.57) | |

| 4–6 | 30 (48.39) | 32 (51.61) | |

| >6 | 69 (75.00) | 2 (25.00) | |

| Dependents members | 0.00 | ||

| ≤4 | 91 (70.54) | 38 (29.68) | |

| >4 | 69 (51.49) | 65 (48.51) | |

| Education | 0.06 | ||

| Graduate | 27 (50.50) | 27 (50.50) | |

| Postgraduate | 133 (63.64) | 76 (36.36) | |

| Occupation | 0.94 | ||

| Salaried | 108 (60.67) | 70 (39.33) | |

| Self-employed | 52 (61.18) | 33 (38.82) | |

| Income | 0.23 | ||

| 1 Lac–3 Lac | 8 (50.50) | 8 (50.50) | |

| 3 Lac–5 Lac | 62 (63.92) | 35 (36.08) | |

| >5 Lac | 90 (60.81) | 58 (39.19) | |

| Medical expenditure | 0.03 | ||

| <5000 | 88 (54.66) | 73 (45.34) | |

| 5001–10000 | 38 (65.52) | 20 (34.48) | |

| >10000 | 34 (77.27) | 10 (22.73) | |

| Health status | 0.00 | ||

| Good | 63 (58.88) | 44 (41.12) | |

| Fair | 55 (61.11) | 35 (38.89) | |

| Poor | 41 (70.69) | 17 (29.31) | |

| Very poor | 1 (12.50) | 7 (87.50) | |

T-test for age. χ2 test for all other variables. P-value: 1%, 5%, and 10% level. ‘%’ figures mentioned in the parentheses.

It was notably observed, respondents having dependents in their families categorized as either ≤4 or ≥4 respectively do own a health insurance policy (70.54% and 51.49%). A significant relationship was administered between education level and insurance status (P= 0.07). Occupation and income showed an insignificant association with the insurance status (P= 0.94 and P= 0.23) in the study. A considerable portion of insured respondents having monthly medical expenditure over Rs 5,000 (45%) had bought a health insurance policy. Respondents experiencing poor health status were found to subscribe more of health insurance (64%) than those possessing a good health.

Table 4 demonstrates the perception the respondents carry about the health insurance product. It can be viewed, 37% of the respondents ‘agreed’ over the statement that by subscribing they will not be benefited. Also, a significant relationship was realized between no benefit and insurance status (P= 0.02). Sixty one percent of the respondent expressed their disagreement over the statement that health insurance will not reduce medical expenditure while only 11% agreed on it. Much of the respondents seemed to oppose the statement that “premium is too high so it is not affordable”, only 15% of the respondent agreed while 46% disagreed. Conditions to subscribe to a health insurance plan shares a statistically significant relationship with insured status (P= 0.01). Seventy percent of the respondents disapproved that “companies create lots of hassles during claims” while only 14% agreed over claim hassles. The perception regarding the claims service shared a significant association with respondent insurance status (P= 0.00).

Table 4 . Perception about the health insurance product and insurance status .

| Variables | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Strongly Agree | F-statistic | P |

| Subscribing a policy will not benefit me | 8.70 | 28.10 | 25.90 | 27.00 | 10.30 | 0.99 | 0.02 |

| It will not reduce my medical expenditure | 10.30 | 50.60 | 28.10 | 11.00 | 0.00 | 3.06 | 0.07 |

| Premium is too high so it is not affordable | 9.10 | 36.90 | 38.40 | 13.70 | 1.90 | 2.41 | 0.99 |

| The eligibility criteria are difficult | 11.40 | 10.30 | 32.70 | 35.00 | 10.60 | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| I find product conditions too complex | 24.30 | 35.40 | 25.90 | 12.50 | 1.90 | 1.15 | 0.01 |

| It does not provide any monetary benefits so its worthless | 17.50 | 35.00 | 24.00 | 23.60 | 0.00 | 3.23 | 0.54 |

| Companies create lots of hassles during claims | 31.20 | 39.50 | 15.20 | 14.10 | 0.00 | 10.23 | 0.00 |

Dependent variable: insurance status (insured and uninsured); Significance level at 1% and 5%. Figures in parentheses are %.

Table 5 highlights the perception of each respondent over their individual personality attributes. About 71% of them explicitly disagreed that they do job thoroughly while 26% were not sure over it. A significant association has been registered between doing the job thoroughly and the insurance status (P= 0.00). Only 22% of the respondents agreed that they tend to get nervous easily while 46% have disagreed to the assertion. A statistical significant association was also noticed between the person nervousness and insurance status (P= 0.03). While other behavioral attributes like being disorganized, makes plans and follows through them and ignorance were found to share no statistical relationship with insurance status (P= 0.15, P= 0.87, P= 0.41).

Table 5 . Individuals personality traits and insurance status .

| Variables | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Strongly agree | F-statistic | P |

| Does my job thoroughly | 25.90 | 44.90 | 26.20 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 0.00 |

| Tends to be disorganized | 5.70 | 11.80 | 20.20 | 41.80 | 20.50 | 1.71 | 0.15 |

| Makes Plan and follows through them | 11.40 | 29.30 | 37.30 | 19.00 | 3.00 | 0.31 | 0.87 |

| Gets nervous easily | 12.50 | 33.80 | 31.90 | 14.10 | 7.60 | 2.78 | 0.03 |

| Tends to be ignorant | 14.80 | 24.70 | 20.50 | 22.10 | 17.90 | 0.99 | 0.41 |

Dependent variable: insurance status (insured and uninsured); significance level at 1% and 5%.

Factors affecting insurance status (logistic regression analysis)

Table 6 presents the results of logistic regression analysis for the variables affecting the insurance status. Model 1 shows the results of individual effects of socio-economic variables. While in model 2 socio-economic variables and individual perception about health insurance product were assessed jointly. On the other hand, model 3 included respondents’ personality traits along with socio-economic and individuals’ product perception variables in the study.

Table 6 . Results of logistic regression analysis for factors influencing the decision to purchase health insurance .

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| β | S.E. | Exp(B) | β | S.E. | Exp(B) | β | S.E. | Exp(B) | |

| Socio-economic Variable | |||||||||

| Age (years) | -0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.89 | -0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.89 | -0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| Marital Status (ref-single) | -0.83 | 0.67 | 0.43 | -0.98 | 0.72 | 0.38 | -1.14 | 0.80 | 0.32 |

| Dependent Members | |||||||||

| 0–2 (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2–4 | -0.26 | 0.69 | 0.79 | -0.34 | 0.75 | 0.71 | -0.39 | 0.81 | 0.67 |

| 4–6 | -1.19* | 0.65 | 0.30 | -1.49** | 0.72 | 0.22 | -1.54** | 0.77 | 0.22 |

| >6 | -3.19*** | 0.87 | 0.04 | -3.49*** | 0.98 | 0.03 | -3.87** | 1.06 | 0.02 |

| Education | |||||||||

| Graduate (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Postgraduate | 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.95 | -0.14 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.81 |

| Medical expenditure | |||||||||

| <2000 (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2000–5000 | 0.82* | 0.54 | 2.27 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 2.10 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 2.23 |

| 5000–10000 | 0.99* | 0.55 | 2.69 | 1.01* | 0.58 | 2.73 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 2.08 |

| >10000 | 2.32*** | 0.62 | 10.16 | 2.04*** | 0.63 | 7.66 | 2.34*** | 0.67 | 10.41 |

| Health status | |||||||||

| Very good/good (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Fair | 0.73* | 0.40 | 2.06 | 0.79* | 0.42 | 2.20 | 0.72* | 0.43 | 2.06 |

| Very poor | -0.30 | 0.47 | 0.74 | -0.40 | 0.49 | 0.66 | -0.37 | 0.54 | 0.69 |

| Perception about Health Insurance product | |||||||||

| Subscribing a policy will not benefit me (ref= agree) | 0.98** | 0.41 | 2.66 | 0.99** | 0.42 | 2.70 | |||

| It will not reduce my medical expenditure (ref= agree) | 1.21** | 1.21 | 3.35 | 1.24*** | 0.46 | 3.46 | |||

| I find product condition too complex (ref= agree) | 0.25 | 0.42 | 1.28 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 1.48 | |||

| Companies creates lots of hassles during claims (ref= disagree) | -0.55 | 0.43 | 0.58 | -0.213 | 0.46 | 0.81 | |||

| Individuals’ personal behavioral factors | |||||||||

| Does my job thoroughly (ref= agreed) | 0.21 | 0.47 | 1.23 | ||||||

| Gets nervous easily (ref= disagree) | 1.64*** | 0.48 | 5.17 | ||||||

| Number of observations (n) | 263 | 263 | 263 | ||||||

| 2 Log likelihood (χ2) | 250.79a | 237.67a | 224.66a | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R 2 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.52 | ||||||

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.38 | ||||||

aLog likelihood at P= 0.01; ***P≤ 0.001; **P≤ 0.05; *P≤ 0.10. Dependent variable= Insurance status (insured and uninsured)

The model presented the Nagelkerke R-squared as 0.43, 0.48 and 0.51 respectively (Table 6). The -2LR for all model were found significant at P< 0.001. It signifies that the models with their predictors were significantly different from one (i.e. all ‘b’ coefficients being at zero). It shows the improvement in the fit that the explanatory variables make compared to the null model. Henceforth, we may elicit that the logit model used was appropriate and in conformity with study.

In model 1, it was noticed that with a gradual increase in the respondent’s age a decreased likelihood to purchase health insurance was determined (OR= 0.89; P< 0.00). A similar trend was even observed in the model 2 and model 3 with respect to age (OR= 0.89 and OR= 0.89). It was also found in the study that the respondent having more number of dependent members in their family showed a lower tendency of purchasing health insurance compared to families having less dependents members. This relationship was found to be statistically significant in all models within a range from P< 0.05 and P< 0.00. Medical expenditure posited significant relationship with respondent decision to purchase health insurance. It was also witnessed that respondents incurring higher medical household expenditure holds 2.20, 2.60 and 10.20 times more odds of purchasing a health insurance compared to respondent with moderate health expenditure. Respondents who perceived their health status as fair showed more chances of coverage under a health insurance plan in all the models with odd ratios 2.06, 2.20 and 2.05 respectively. While those having a poor health status have found less odds to be covered under a health insurance plans, though it have not showed any statistical significance in the study.

Perception of respondents’ about the health insurance product was even determined to examine its impact on their health insurance purchase. Respondents who disagreed to the statement that subscribing a policy will not benefit me showed more odds to purchase health insurance in the model 2 (OR= 2.66). While on the other hand, respondent who disagreed to the assertion that it will not reduce my medical expenditure were 3.50 times more likely to purchase the health insurance compared to those who agreed (P< 0.05).

The individual’s personality traits also affected the respondents’ decision to purchase health insurance plans. Respondents who agreed to the assertion getting nervous easily, posited more odds to purchase health insurance plans in the model 3 (OR= 5.17) significantly (P< 0.01).

Discussion

On a broader note, an extreme difference in the rate of participation has been observed between the insured and uninsured. In the sample study, 160 respondents (60.40%) have purchased a health insurance cover whilst remaining 103 respondents (39.60%) were not covered under any form of health insurance plan. The level of participating information obtained in the sample was however found to be inconsistent with existing structure of health insurance in India as showcased by the past reports (1,33). This inconsistency could be attributed to the increased knowledge about health insurance plans and benefits within the sampled universe.

Socio-economic factors and health insurance purchase

Results of this study demonstrated the effect of socio-economic variables have on the individual purchase behavior for health insurance plans. It was revealed that age of the respondents’ acts as a significant determinant to one’s insurance status. A lower propensity to purchase health insurance was determined with an increase in respondents’ age. This premise sets on the ground of eligibility limitations as people falling under higher age brackets are usually disallowed from subscribing to the health insurance products in India (people with 45 years of age or above need to undergo a medical checkup before purchasing a plan; and maximum allowable age is 65 years for most plans)3. People in older age are vulnerable hence prone to illnesses and ailments which amplify hospital utilization rates which ultimately adversely effects insurers’ profitability (34,35). Thus supply side constraint becomes a barrier for people especially in the older age brackets, leading to lower subscription rates for the product (36).

In the study, a lower propensity to purchase health insurance plans was noticed among the individuals having large number of dependent members compared to lesser dependent members in the household. This behavior indicates that insurance status is even contingent upon the size of the dependent members in a family. High household expenditure may be linked as a cause for lower policy subscription rates, as it diminishes the household’s insurance expenditure (37). Further, joint family system still prevails in the Indian social structure; therefore, a large portion of the family income goes in fulfilling the consumption needs thus reducing the scope for investment into the other essential items. On the supply front, companies which are offering health insurance coverage for entire family follows a strict and complex conditions for enrollment like medical tests, high deductibles, premium loadings, copayments clauses, etc. which further lessens the penetration of this product.

The research findings also showed that respondents with higher medical expenditure were more likely to buy health insurance compared to respondents with lower medical expenses. This outcome was analogous to the studies carried in the past under the similar framework (38–40). In conformity to past literature it was found that people who were frequently spending on medical care, either on themselves or on their family, were more inclined to purchase health insurance to trim down their economic burden.

The health status of the respondents has also reasonably impacted the insurance status in the study. The results showed that respondents who perceived to have fair health possesses a health insurance plan while the respondents with poor health status displayed lower subscription to the health insurance plan. The lower participation of respondents could be due to the suppliers’ deterrence to cover people having poor health status and thus overcoming the issue of adverse selection and moral hazard (41).

Health insurance product perception and health insurance purchase

The study depicted that positive perception about the health insurance benefits has a reasonable impact on its purchasability. It was made evident as respondents adverted “subscribing a policy will not benefit me” as a reason for not purchasing health insurance policy. Other reason cited for not purchasing the health insurance by the respondent was “It will not reduce my medical expenditure”. Unaffordability of premium has been cited by the respondents as a primal reason for staying uninsured in the study (42). Lack of monetary benefits or non-financial returns were also amongst the probable reasons for not subscribing to a health insurance plan given by the respondents. In addition, terms and conditions of the health insurance plans have been witnessed by the respondents to be complex and incomprehensible, hence cited as a probable reason for non-purchase. Finally, a negative notion (based on other customer experiences) regarding services during a claim occurrence have been reiterated by many respondents as an obvious cause for not purchasing health insurance (43).

From the above reactions it can be deduced that people posit less faith in the product. This may be due to the high level of deductibles and preconditions in the plans which restrict its purchasability4. Even inadequate policy sum insured and limit to number of beneficiaries’ coverage in a family forms an acute reason for people not subscribing to these plans wholesomely. Therefore a serious transformation is desired in terms of product design and a service quality standard from the insurers in the health insurance segment.

Individual’s personality traits and health insurance purchase

A significant relationship was observed between the respondents’ personality traits and insurance status. It was noticed that respondents who perform their personal routine activities diligently were more sincere in subscribing to a health insurance cover. This reflects a cautious approach and readiness towards future uncertainties of life. Further, in the study it was observed that people who get nervous frequently showed more likelihood for subscribing to the health insurance plan compared to people who get less nervous in their life. It depicts the general nature people behold against untoward events. To estrange themselves from anxiety and strenuousness nature of life they subscribe to the health insurance plans which guard them during an extreme health calamity.

Limitation of study

The study might fall short to several other factors which directly or indirectly influence the respondents’ insurance status. The study did not take the views and opinions of the insurance companies and regulators which may have provided a distinctive or rather contrary perspective over the reason for low participation. This opens wide area for researchers to further investigate. Psychological and emotional aspects on a likert scale may not display complete picture in entirety. Thus researchers can include case studies to showcase respondent opinions and views. Lastly, models used in the study did not take into consideration any assessment on likely interactive effects that could be emanating from the predictive indicators as the study was trying to only assess the predictive power of the model. But interaction terms if used in the study may have added another dimension to the outcome variable.

Conclusion

It can be discerned from the study that socio-economic, product perception and individual personality traits does lay a significant impact on the individual’s decision to subscribe for PVHI plans. The eagerness and sensitivity people hold towards this product was also displayed in the study. Subsequently, imbalances created by certain socio-economic conditions (restricted to the present results) keep people quite distant from the health insurance coverage. To address and overcome these challenges companies must shift focus on designing and offering affordable health insurance plans with uncomplicated conditionalities. Areas like timely claims settlement, transparency in policy guidelines and increase usability of technology must continue to remain the utmost priorities for the insurance companies. By reducing persisting enigma about the health insurance, will certainly build faith and confidence among the customers.

Endnotes

1. The term PVHI was used for the health insurance plans offered by commercial entities (both public entities and private entities). (As referred from page 23, of book titled “Government Sponsored Health Insurance in India: Are You Covered” by Gerard La Forgia and Somil Nagpal).

2. The income group classification standards for lower, middle and upper were estimated as per the report published by Mckinsey Global Institute in 2007 titled as “The Bird of Gold: The Rise of India’s Consumer Market”. (As per their estimates, lower-income group= INR 90,000–200,000; Middle-income group= INR 200,000–1,000,000; Upper-income group≥ INR 1,000,000, these figures are annual household income).

3. Majority of non-life insurance offering health insurance plans fixed the maximum enterable age at 65 (as standardized by IRDA regulation 2012). Also special provision been laid for insurer for filing products related with higher entry age limits [Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA), health insurance regulation 2012, 6.1, 6.2].

4. The health insurance plans offered by public and private non-life insurance companies have some standard exclusion in the initial years of the policy tenure. Most of the day care treatments carry 2 year exclusions and treatments over 24 hrs of hospitalization have 3 to 4 years of exclusions on certain ailments. The exclusions are referred to as ‘pre-existing diseases’ in the policy terms (Health Insurance handbook by IRDA, 2012).

Ethical issues

Ethical principles were followed throughout the conduct of this research. Informed consent was also obtained from each respondent. Also the anonymity of each respondent was maintained in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s Contributions

TM, UKP, HNP and SCD were involved in designing of the study. TM has collected the data for the study. UKP and SCD assisted TM during data analysis. TM wrote the first draft of the article. UKP and HNP reviewed and commented on all subsequent drafts.

Key messages

Implications for policy makers

Insurance regulator may act upon simplifying the health insurance policy wordings along with standardization in hospitalization treatment procedures and costs.

Companies must essentially improve their health insurance product design by keeping the customers prerogative.

Amelioration in the claims settlement procedures should be the foremost area of focus.

The managers of the companies must reframe their sales strategies according to the nature of the customer since perception about the product and personality traits do impact decision-making.

Implications for public

The results of the study showed how the socio-economic factors, individuals product perception and individuals personality traits influences health insurance policy subscription. It was found from the results that age, high medical expenditure, positive attitude about the plans and nervous nature drive individuals to purchase health insurance plans.

Citation: Mathur T, Paul UK, Prasad HN, Das SC. Understanding perception and factors influencing private voluntary health insurance policy subscription in the Lucknow region. Int J Health Policy Manag 2015; 4: 75–83. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.08

References

- 1. Reddy KS, Selvaraj S, Rao KD, Chokshi M, Kumar P, Arora V, et al. A Critical Assesment of the Existing Health Insurance Models in India. Public Health Foundation of India; 2011.

- 2. La Forgia G, Nagpal S. Government Sponsored Health Insurance in India: Are you covered? Washington, DC:The World Bank Publications; 2011. doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-9618-6.

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Observatory Data Repository [internet]. 2014 [updated June 2014; cited 2014 October 16]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.country.country-IND.

- 4. Dinodia Capital Advisors New Delhi. Indian Healthcare Industry 2012. [cited 2014 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.dinodiacapital.com/admin/upload/Indian-Healthcare-Industry-November-2012.pdf.

- 5.Rajeev A, Narang A. Emerging Trends in Health Insurance for Low-Income Groups. Econ Polit Wkly. 2005;40:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sapelli C, Torche A. The Mandatory Health Insurance System in Chile: Explaining the Choice between Public and Private Insurance. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2001;1:97–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1012886810415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Central Statistical Office. National Accounts Statistics. New Delhi: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation Government of India; 2013.

- 8. The Planning Commission, Government of India, Report of the Working Group on Savings during the Twelfth Five- Year Plan (2012) [Cited 2014 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?ID=662.

- 9. Sinha T. An Analysis of the Evolution of Insurance in India. In: Cummins JD, Venard B, editors. Handbook of International Insurance. Springer US; 2007. p. 641-78.

- 10.Mahal A. Assessing private health insurance in india-potential impacts and regulatory issues. Econ Polit Wkly. 2002;37:559–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao S. Health insurance concepts, issues and challenges. Econ Polit Wkly. 2004;39:3835–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta I. Private health insurance and health costs- results from a Delhi study. Econ Polit Wkly. 2002;37:2795–02. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mcdonald EM, Shannon F, Edsall Kromm E, Ma X, Pike M, Holtgrave D. Improvements in health behaviors and health status among newly insured members of an innovative health access plan. J Community Health. 2012;345:1106–12. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenman R, Wang HH. Perceived need and actual demand for health insurance among rural chinese residents. China Economic Review. 2006;18:373–88. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2006.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saver, Barry G, Doescher, Mark P. To buy, or not to buy, factors associated with the purchase of nongroup, private health insurance. Med Care. 2000;38:141–51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200002000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lave J, Keane CR, Lin CJ, Ricci EM, Amersbach G, LaVallee CP. The impact of a children’s health insurance program by age. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1051–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.5.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monheit AC, Vistnes JP. Health insurance enrollment decisions: preferences for coverage, worker sorting and insurance take-up. Inquiry. 2008;45:153–67. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_45.02.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadley J. Sicker and poorer--the consequences of being uninsured: a review of the research on the relationship between health insurance, medical care use, health, work, and income. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60:3S–75S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703254101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumberg LJ, Nichols LM, Banthin JS. Worker decisions to purchase health insurance. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2001;1:305–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1013771719760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boateng D, Awunyor-Vitor D. Health insurance in ghana:evaluation of policyholder’s perception and fators influencing policy renewal in the Volta region. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:50. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jovanovic Z, Lin CJ, Chang CC. Uninsured vs insured population: variations among nonelderly Americans. J Health Soc Policy. 2003;17:71–85. doi: 10.1300/j045v17n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RE. Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy on Perceived Product Performance. J Mark Res. 1973;10:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodds WB, Monroe nd Grewal D KB, Grewal D. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J Mark Res. 1991;28:307–19. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichtenstein DR, Ridgway NM, Netemeyer RG. Price perceptions and consumer shopping behavior: a field study. J Mark Res. 1993;30:234–45. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang TZ, Wildt AR. Price, product information, and purchase intention: an empirical study. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 1994;22:16–27. doi: 10.1177/0092070394221002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor SA, Baker TL. An assessment of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in the formation of consumers’ purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing. 1994;70:163–78. doi: 10.1016/0022-4359(94)90013-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cronin JJ Jr, Brady MK, Hult GT. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing. 2000;76:193–218. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4359(00)00028-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulyanegara RC, Tsarenko Y, Anderson A. The big five and brand personality: investigating the impact of consumer personality on preferences towards particular brand personality. Journal of Brand Management. 2009;16:234–47. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauriola M, Levin IP. Personality traits and risky decision-making in a controlled experimental task: an exploratory study. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31:215–26. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00130-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert ZV. Price and choice behavior. J Mark Res. 1972;9:35–40. doi: 10.2307/3149603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAdams DP. Personality, modernity, and the storied self: a contemporary framework for studying persons. Psychol Inq. 1996;7:295–321. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0704_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McAdams DP. The person: an integrated introduction to personality psychology. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers; 2001.

- 33. Insurance Regulatory Development Authority (IRDA). [cited 2014 August 28]. Available from: http://www.irda.gov.in/ADMINCMS/cms/Uploadedfiles/IRDA_Health%20Insurance_%20Regulation%202012.pdf.

- 34.Baker DW, Sudano JJ, Albert JM, Borawski EA, Dor A. Lack of health insurance and decline in overall health in late middle age. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1106–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa002887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harmon C, Nolan B. Health insurance and health services utilization in Ireland. Health Econ. 2001;10:135–45. doi: 10.1002/hec.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reschovsky JD, Kemper P, Tu H. Does type of health insurance affect health care use and assessments of care among the privately insured? Health Serv Res. 2000;35:219–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Showers VE, Shotick JA. The effects of household characteristics on demand for insurance: a tobit analysis. The Journal of Risk and Insurance. 1994;61:492–502. doi: 10.2307/253572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jowett M, Contoyannis P, Vinh ND. The impact of public voluntary health insurance on private health expenditures in Vietnam. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:333–42. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnan TN. Hospitalisation insurance: a proposal. Econ Polit Wkly. 1996;31:944–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362:111–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pauly MV. The economics of moral hazard: comment. Am Econ Rev. 1968;58:531–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frank RG, Lamiraud K. Choice, price competetion and complexity in markets for health insurance. J Econ Behav Organ. 2006;72:550–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2009.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohammed S, Sambo MN, Dong H. Understanding client satisfaction with a health insurance scheme in Nigeria: factors and enrollees experiences. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]