Summary

The incidence of breast cancer (BC) in postmenopausal women is continuously rising. Due to early diagnosis and various treatment designs, the long-term clinical outcome has improved. Frequent settings are chemotherapy as well as endocrine treatment. Both have proven to interfere with bone health resulting in cancer treatment-induced bone loss (CTIBL). Whereas chemotherapy is associated with increased bone resorption, aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy reduces residual estrogen and is associated with decreased bone mineral density. Independent of the AI administered, the loss of bone mineral density is twice as high compared to healthy postmenopausal women. As a consequence of CTIBL, both chemotherapy and AI treatment can lead to a significantly increased fracture risk. Therefore, several guidelines have emerged for the management of CTIBL in women with BC, including strategies to identify and treat those at high risk for fractures. Further research on tracking guideline adherence examining the feasibility and practicability of guideline implementation to bridge the gap between determined scientific best evidence and applied best practice is needed to adjust these guidelines in the future.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Breast cancer, Bone mineral density, Aromatase inhibitor-induced bone loss, AIBL, Cancer treatment-induced bone loss, CTIBL

Introduction

In the USA, Europe, and Japan, over 75 million people have a diagnosis of osteoporosis. Worldwide, over 8.9 million osteoporosis-related fractures occur annually, of which 4.5 million are documented in America and Europe. The lifetime risk of sustaining an osteoporosis-related fracture is estimated at 30–40% in the industrial nations, which is coming close to the frequency of coronary heart disease. The DALY (disability-adjusted life years) concept of the World Health Organization summarizes osteoporosis-related fractures to account for approximately 1% of DALYs (2.8 million DALYs) worldwide. In their ranking, osteoporosis is ahead of hypertension and rheumatoid arthritis, and right behind diabetes mellitus and chronically obstructive lung disease [1].

Based on an extrapolation of the Bone Evaluation Study (BEST), 6.3 million people (5.2 million women and 1.3 million men) are currently affected by osteoporosis in Germany. The annual incidence of new cases is estimated at 885,000 people [2]. The fracture incidence of 51% in osteoporosis patients is considerably higher than assumed in earlier epidemiological studies [2, 3].

Osteoporosis is defined as a skeletal disorder characterized by compromised bone strength predisposing to an increased risk of fracture. Bone strength reflects the integration of 2 main features: bone density and bone quality [4]. In addition, osteoporosis is defined based on bone mineral density (BMD) T-scores which represent a measured value 2.5 standard deviations below the average of a control collective of young women and men [1, 5]. The guideline of the German umbrella association Osteology (Dachverband Osteologie, DVO) integrates both the definition of osteoporosis and clinical aspects, and, besides the diagnosis of a low BMD, especially considers clinical risk factors as well as the influence of medical therapy on the risk for fractures [6].

One important risk factor for the increasing incidence of osteoporosis is tumor- and therapy-induced osteoporosis which is discussed in this review using the example of breast cancer (BC) as the most common malignant disease among women. Following information from the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), the age-related standardized incidence of women with BC in Germany has almost doubled since the 1980s. Up until 2004, the incidence of new cases increased by 65% to approximately 57,000 newly diagnosed women annually, with an almost constant BC-induced absolute high mortality of approximately 18,000 women annually since 1990. According to the RKI, the incidence rate for 2010 with 70,340 women is continuously rising. Following the prognosis in 2014, the incidence rate for newly diagnosed BC in women will be an expected 75,200. At the same time, an improved relative 5-year survival rate of 81% is reported for patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2004, compared to 69% in the 1980s. With a prevalence of almost 1% of the female population in Germany, BC is spearheading the list of malignant diseases in women [7].

From Pathophysiology and Evidence to Guidelines

Between BC and osteoporosis, a considerable connection exists which is attributable to the estrogen metabolism. In the 1980s, it was proven that the classic risk factors for BC (early menarche, late menopause, obesity, nulliparity, advanced age at birth of first child), besides a familial disposition, are linked with increased endogenous or exogenous estrogen exposure time. The risk factors associated with estrogen exposure support on the one hand the development of BC but should on the other hand be protective against bone loss and the development of osteoporosis [8]. Circulating sex hormones possibly represent the mediator for the effects of these factors on the risk of BC [9].

In the 1990s, it was well documented that estrogen has a protective effect on human bone cells when directly transmitted by an estrogen receptor [10]. Estrogens exert a direct receptor-transmitting effect on bone metabolism via osteoblasts and osteoclasts, and have an indirect influence through cytokines and mediators such as transforming-growth factor beta, leptin, neuropeptide Y, tumor necrosis factor, insulin-like growth factor 1, interleukin (IL)-1, and IL-6. These mediators and cytokines have a proliferative effect on the mammary tissue, and are considered risk factors influencing the development of BC and its therapeutic approach [10, 11].

In the healthy reproductive state, the relationship between osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclastic bone resorption is balanced [12]. After menopause, a critical change in this process occurs. Besides the classical symptoms (e.g. hot flushes, mucosal atrophy) caused by physiologically decreased plasma levels of estriol, bone health is majorly impacted. Although individually varying, healthy postmenopausal women experience a gradual bone loss of 1% per year [13, 14].

Bone-Related Effects of Treatment in Postmenopausal Women with BC

Chemotherapy and endocrine treatment are known to harm the bone metabolism.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapeutics such as taxane, doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and cisplatin cause an increase in bone resorption independent of bone metastasis and a reduction in bone structure. Animal models have shown a 60% reduction in trabecular bone structure. These effects of chemotherapy are in addition to the increased activity of osteoclasts in women with BC [15, 16]. In a case-control study with 352 postmenopausal women, a 5-fold increased incidence of fractures per year and a 2.8-fold increased relative risk in women with primary BC was observed. Women with recurrent BC showed a 6-fold increase in fracture incidence even at the beginning of the study, and a 23-fold increased incidence annually as well as a 24.5% increased relative risk [17].

Endocrine Treatment

Treatment with tamoxifen (TAM) in postmenopausal women with BC is well known to increase BMD [18, 19, 20]. According to a randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded trial, an increase in BMD was observed in women who received TAM compared to an annual decrease in the control group (0.6 vs. 1.0%, respectively). The same study showed a significant decrease in the incidence of fractures in the TAM-treated women with BC [18, 21]. In addition to the increased BMD, a significant improvement in bone structure was also shown [22, 23].

With regard to the mechanism of action, aromatase inhibitors (AI) inhibit the activity of the aromatase enzyme leading to a decrease in plasma estradiol [24]. AI-induced estrogen deficiency results in negative bone metabolism with increased markers of bone resorption, as well as a decreased BMD and increased fracture risk [25]. Aromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss (AIBL) occurs at a rate at least 2-fold higher than loss of BMD seen in healthy, age-matched, postmenopausal women, resulting in a significantly higher incidence of fractures regardless of the AI administered [13].

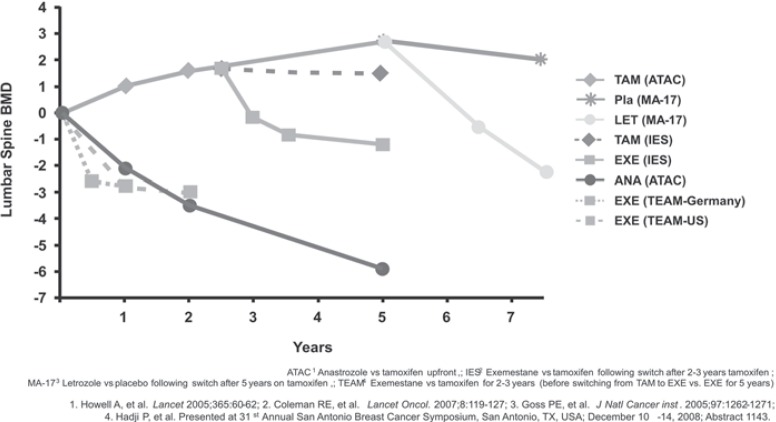

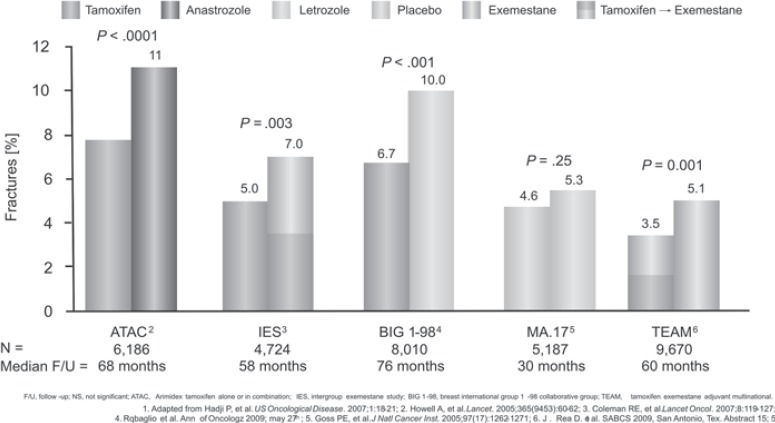

Besides a decreased BMD, bone structure assessed by the trabecular bone score (TBS) was also significantly decreased at the lumbar spine and the hip after 2 years of anastrozole treatment [23]. Figures 1 and 2 show the influence of various AI on BMD and fracture risk [26, 27, 28, 29, 30].

Fig. 1.

Influence of treatment with aromatase inhibitors on bone mineral density (BMD) [54].

Fig. 2.

Influence of treatment with aromatase inhibitors on fracture risk (data not from direct comparison) [54].

Guidelines to Manage AIBL/Cancer Treatment-Induced Bone Loss

Guidelines for AIBL in postmenopausal women with BC emerged in 2008 [31]. These were applicable at first in high-risk patients aged below 45 years in whom treatment caused early menopause, and postmenopausal women treated with AI.

The different endocrine treatment regimens (5 years of TAM; 5 years of AI; 2 or 3 years of TAM followed by 2 or 3 years of AI; 2 or 3 years of AI followed by 2 or 3 years of TAM; 5 years of TAM followed by 5 years of AI) are well established in the S-III guidelines for treatment of BC [32].

The side effect profile of AI in comparison to TAM shows on the one hand fewer cases of endometrial cancer, thrombosis, and hot flushes, but on the other hand a higher rate of myalgia and arthralgia and loss of BMD with subsequent higher rates of osteoporotic fractures [32].

Since endocrine treatment with AI in women with BC is an inherent part of the guidelines, prevention of AIBL is essential. Hence, diagnosis and recommendations for AIBL were integrated in the guideline ‘Diagnosis, Therapy and Follow-Up of Breast Cancer’ in 2012 [32].

The estimated risk for an osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal women is 1–2-fold increased in patients with AIBL compared to healthy controls. The DVO guidelines therefore recommend baseline diagnostics for postmenopausal women with BC treated with AI to estimate the individual future fracture risk and implement measures to prevent bone loss [6]. Through a review of the literature, 8 factors have been identified to sufficiently estimate the fracture risk of patients with AIBL (fig. 3) [33]. Recently, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) confirmed the reported risk factors that increase fracture risk in postmenopausal women with BC. Recommendation level A is assigned for the process of fracture risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of AIBL, which is shown in figure 3 [12].

Fig. 3.

International guideline for managing bone health during cancer treatment [12] (BMI = Body mass index).

aIncludes aromatase inhibitors and ovarian suppression therapy/oophorectomy for breast cancer, and androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer.

bIf patients experience an annual decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) of ≥ 10% (or ≥ 4–5% in patients who were osteopenic at baseline) using the same DXA machine, secondary causes of bone loss such as vitamin D deficiency should be evaluated and antiresorptive therapy initiated. Use lowest T-score from spine and hip.

c6-monthly intravenous zoledronic acid, weekly oral alendronate or risedronate or monthly oral ibandronate acceptable.

dDenosumab may be a potential treatment option in some patients.

eAlthough osteonecrosis of the jaw is a very rare event with bone-protective doses of antiresorptives, regular dental care and attention to oral health is advisable.

Practical Aspects of the Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis

In order to prevent bone loss in postmenopausal women with BC during the treatment course, an adequate assessment of fracture risk factors at baseline as well as BMD measurement are strongly recommended [12].

Studies on physical activity for prevention of osteoporosis have shown diverse results [34, 35]. A case-control study showed a delay in the loss of BMD in 66 pre- and post-menopausal women with BC using either aerobic exercise (–0.8%) or weight training (–4.9%) compared to a control group [36]. In the current guidelines (ESMO, DVO), the level of evidence and the degree of recommendation are still low (4/C) [6, 12]. Recent reports provided evidence that physical activity for 3 h per week decreases BC-related morbidity and mortality [37]. In addition, lifestyle changes such as reduced alcohol consumption and refraining from smoking are recommended [12].

Adequate intake of calcium (1,000 mg/day) and supplementary vitamin D (1,000–2,000 units/day) administered to postmenopausal women with osteopenia to prevent bone loss is well documented with regard to osteoporosis [35, 38]. Life-long intake of calcium is known to decrease the risk of osteoporosis by up to 20% [39]. According to an analysis of 45 trials with individuals living in nursing homes, the rate of hip fractures is reduced in those using calcium and vitamin D supplements [40]. This result was confirmed by a meta-analysis in postmenopausal elderly women and men (n = 45,509) that reported a decreased fracture risk of 18% [38]. However, administration of calcium and vitamin D alone cannot prevent AIBL.

Bone-Directed Antiresorptives to Decrease the Incidence of Osteoporotic Fractures

A number of antiresorptives have emerged for the management of cancer treatment-induced bone loss (CTIBL). Most relevant antiresorptives decrease the rate of typical osteoporotic fractures such as vertebral and non-vertebral fractures. The overall effect across 9 antiresorptives in preventing vertebral and non-vertebral fractures was odds ratio (OR) = 0.49 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.41, 0.58) and OR = 0.81 (95% CI 0.77, 0.86) (p < 0.01), respectively, indicating a protective effect on bone health [41].

It is reported that the recombinant amino-terminal fragment of human parathyroid hormone, teriparatide, reduces vertebral and non-vertebral fractures (65 vs. 53%, respectively). Because of the high costs, teriparatide remains reserved for severe cases of osteoporosis [42]. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs, e.g. raloxifene or bazedoxifen) showed a 50% reduction in vertebral fractures compared to placebo, but did not influence any other typical region of osteoporotic fractures [43]. Recently, it was reported that the monoclonal antibody denosumab reduces vertebral (68%) and non-vertebral (19%) fracture rates in patients with osteoporosis [44]. Furthermore, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has the potential to reduce osteoporotic fracture rates in comparison to placebo [45]; however, in the presence of BC, HRT is contraindicated.

Therapy with Bisphosphonates and Denosumab to Prevent AIBL

With the administration of intravenous bisphosphonates or subcutaneous denosumab, AIBL or androgen deprivation in the treatment of prostate cancer can be prevented [46]. A number of small-scale prospective controlled randomized trials could also demonstrate the effectiveness of oral bisphosphonates in the prevention of AIBL [47]. The majority of data was assessed using intravenous bisphosphonates (e.g. 4 mg zoledronic acid twice a year) to prevent AIBL in women with a high fracture risk [33]. These results were confirmed by 4 randomized controlled studies with more than 4,000 women with BC, who were treated with an AI [48, 49, 50, 51].

Due to decreased estrogen levels, secretion of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) is increased. At the same time, osteoclast expression of osteoprotegerin is decreased; hence, osteoclast activity is increased resulting in decreased bone mass.

A significant increase in BMD in 252 postmenopausal women with BC receiving the human monoclonal antibody denosumab has been reported (+5.5% after 12 months and +7.6% after 24 month). If administration of denosumab is withdrawn, inhibition of RANKL and suppression of osteoclast activity are reversed immediately, which results in the consecutive loss of BMD [52]. Denosumab decreased the risk for osteoporotic fractures sufficiently and is therefore an effective alternative for the prevention and treatment of AIBL in postmenopausal women [53].

Conclusion

In conclusion, chemotherapy and/or endocrine treatment in postmenopausal women with BC frequently cause CTIBL. Therefore, several guidelines have emerged for the management of CTIBL and the prevention and/or treatment of osteoporosis-related increased bone resorption and fractures. Patients for whom chemotherapy and/or endocrine treatment has been recommended should be counseled with regard to monitoring BMD at baseline before treatment, physical exercise, and calcium/vitamin D supplementation. Patients with a T-score of > −2.0 and no further risk factors should be monitored based on risk factors and BMD loss at 1–2–year intervals. In patients with at least 2 risk factors for fractures and a T-score of < −2.0, initiation of a bone-directed therapy and compliance monitoring are recommended. Further research on tracking guideline adherence examining the feasibility and practicability of guideline implementation to bridge the gap between determined scientific best evidence and applied best practice is needed to adjust these guidelines in the future.

Disclosure Statement

Peyman Hadji has received honoraria, unrestricted educational grants, and research funding from the following companies: Astra Zeneca, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Wyeth. Matthias Kalder has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO: WHO Scientific Group on the Assessment of Osteoporosis at Primary Health Care. Summary Meeting Report. 2004.

- 2.Hadji P, Klein S, Gothe H, et al. The epidemiology of osteoporosis – Bone Evaluation Study (BEST): an analysis of routine health insurance data. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:52–57. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robert Koch Institut: Prävalenz der Osteoporose. ‘Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung’ GEDA 2009. Berlin, RKI. 2009.

- 4.No authors listed: Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. NIH Consens Statement. 2000;17:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson-Hughes B, Looker AC, et al. The potential impact of the National Osteoporosis Foundation guidance on treatment eligibility in the USA: an update in NHANES 2005-2008. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:811–820. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1694-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DVO G. DVO-Guideline 2009 on the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoporosis in Adults. Osteologie. 2009;18:304–324. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert Koch Institut: Verbreitung von Krebserkrankungen in Deutschland. Entwicklung der Prävalenzen zwischen 1990 und 2010. Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Berlin, RKI. 2010.

- 8.Kalder M, Jager C, Seker-Pektas B, et al. Breast cancer and bone mineral density: the Marburg Breast Cancer and Osteoporosis Trial (MABOT II) Climacteric. 2011;14:352–361. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.557754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Key TJ, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, et al. Circulating sex hormones and breast cancer risk factors in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of 13 studies. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:709–722. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horowitz MC. Cytokines and estrogen in bone: anti-osteoporotic effects. Science. 1993;260:626–627. doi: 10.1126/science.8480174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadji P, Gottschalk M, Ziller V, et al. Bone mass and the risk of breast cancer: the influence of cumulative exposure to oestrogen and reproductive correlates. Results of the Marburg breast cancer and osteoporosis trial (MABOT) Maturitas. 2007;56:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman R, Body JJ, Aapro M, et al. Bone health in cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2014;25((suppl 3)):iii124–iii137. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadji P. Aromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss in breast cancer patients is distinct from postmenopausal osteoporosis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;69:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reginster JY, Deroisy R, Albert A, et al. Relationship between whole plasma calcitonin levels, calcitonin secretory capacity, and plasma levels of estrone in healthy women and postmenopausal osteoporotics. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1073–1077. doi: 10.1172/JCI113950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delmas PD, Fontana A. Bone loss induced by cancer treatment and its management. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:260–262. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greep NC, Giuliano AE, Hansen NM, et al. The effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on bone density in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. Am J Med. 2003;114:653–659. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Powles T, et al. A high incidence of vertebral fracture in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1179–1181. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love RR, Mazess RB, Barden HS, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:852–856. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203263261302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turken S, Siris E, Seldin D, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on spinal bone density in women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1086–1088. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.14.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner RT, Wakley GK, Hannon KS, Bell NH. Tamoxifen prevents the skeletal effects of ovarian hormone deficiency in rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2:449–456. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadji P, Ziller M, Kieback DG, et al. The effect of exemestane or tamoxifen on markers of bone turnover: results of a German sub-study of the Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multicentre (TEAM) trial. Breast. 2009;18:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalder M, Hans D, Kyvernitakis I, et al. Effects of Exemestane and Tamoxifen treatment on bone texture analysis assessed by TBS in comparison with bone mineral density assessed by DXA in women with breast cancer. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton A, Piccart M. The third-generation nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors: a review of their clinical benefits in the second-line hormonal treatment of advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:377–384. doi: 10.1023/a:1008368300827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhesy-Thind SK. Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors: less is more? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1408–1410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.No authors listed: Abstracts of the 27th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. December 8-11, 2004, San Antonio, Texas, USA: Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;88((suppl 1)):S1–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–1092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, et al. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadji P, Asmar L, Van Nes JG, et al. The effect of exemestane and tamoxifen on bone health within the Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multinational (TEAM) trial: a meta-analysis of the US, German, Netherlands, and Belgium sub-studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1015–1025. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0964-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabaglio M, Sun Z, Price KN, et al. Bone fractures among postmenopausal patients with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer treated with 5 years of letrozole or tamoxifen in the BIG 1-98 trial. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1489–1498. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid DM, Doughty J, Eastell R, et al. Guidance for the management of breast cancer treatment-induced bone loss: a consensus position statement from a UK Expert Group. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34((suppl 1)):S3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.S3 L: Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie für die Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinomsed. AWMF-Register-Nummer: 032-045OL, Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie der AWMF, Deutschen Krebsgesellschaft e.V. und Deutschen Krebshilfe e.V. 2012.

- 33.Hadji P, Aapro MS, Body JJ, et al. Management of aromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: practical guidance for prevention and treatment. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2546–2555. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hojan K, Milecki P, Molinska-Glura M, et al. Effect of physical activity on bone strength and body composition in breast cancer premenopausal women during endocrine therapy. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;49:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siris ES, Brenneman SK, Barrett-Connor E, et al. The effect of age and bone mineral density on the absolute, excess, and relative risk of fracture in postmenopausal women aged 50-99: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA) Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:565–574. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz AL, Winters-Stone K, Gallucci B. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:627–633. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.627-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Manson JE, et al. Physical activity and survival in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: results from the women's health initiative. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:522–529. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:669–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nieves JW, Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES, et al. Calcium and vitamin D intake influence bone mass, but not short-term fracture risk, in Caucasian postmenopausal women from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA) study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:673–679. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0501-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avenell A, Gillespie WJ, Gillespie LD, O'Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures associated with involutional and post-menopausal osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD000227. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000227.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hopkins RB, Goeree R, Pullenayegum E, et al. The relative efficacy of nine osteoporosis medications for reducing the rate of fractures in post-menopausal women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:209. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rizzoli R, Kraenzlin M, Krieg MA, et al. Indications to teriparatide treatment in patients with osteoporosis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13297. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, et al. Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1923–1934. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christenson ES, Jiang X, Kagan R, Schnatz P. Osteoporosis management in post-menopausal women. Minerva Ginecol. 2012;64:181–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cauley JA, LaCroix AZ, Robbins JA, et al. Baseline serum estradiol and fracture reduction during treatment with hormone therapy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0953-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saad F, Adachi JD, Brown JP, et al. Cancer treatment-induced bone loss in breast and prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5465–5476. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saarto T, Vehmanen L, Blomqvist C, Elomaa I. Ten-year follow-up of 3 years of oral adjuvant clodronate therapy shows significant prevention of osteoporosis in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4289–4295. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brufsky AM, Harker WG, Beck JT, et al. Final 5-year results of Z-FAST trial: adjuvant zoledronic acid maintains bone mass in postmenopausal breast cancer patients receiving letrozole. Cancer. 2012;118:1192–1201. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coleman R, de Boer R, Eidtmann H, et al. Zoledronic acid (zoledronate) for postmenopausal women with early breast cancer receiving adjuvant letrozole (ZO-FAST study): final 60-month results. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:398–405. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gnant MF, Mlineritsch B, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, et al. Zoledronic acid prevents cancer treatment-induced bone loss in premenopausal women receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy for hormone-responsive breast cancer: a report from the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:820–828. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy plus zoledronic acid in premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: 5-year follow-up of the ABCSG-12 bone-mineral density substudy. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:840–849. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ellis GK, Bone HG, Chlebowski R, et al. Randomized trial of denosumab in patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for nonmetastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4875–4882. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silva-Fernandez L, Rosario MP, Martinez-Lopez JA, et al. Denosumab for the treatment of osteoporosis: a systematic literature review. Reumatol Clin. 2013;9:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalder M, Hadji P, editors. Tumortherapieassoziierte Osteoporose; in Stenzl A; Fehm T Hofbauer LC et al (eds): Knochenmetastasen. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 139–165. [Google Scholar]