Summary

Background

This retrospective analysis was planned as a direct comparison of taxanes plus trastuzumab to the less toxic combination of oral vinorelbine (OV) plus trastuzumab as a first-line therapy for metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients (n = 76) receiving either taxanes (group A) or OV (group B) in combination with trastuzumab were identified from a breast cancer database. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the primary study endpoint; secondary endpoints were overall survival (OS), response rate (RR), incidence of brain metastases, and brain metastases-free survival (BMFS).

Results

36 patients received taxanes and 40 patients OV in combination with trastuzumab. At a median follow-up of 47.5 months, median PFS was 7 months (group A) and 9 months in group B (log-rank; non-significant), respective numbers for OS were 49 and 59 months (p = 0.033). The incidence of brain metastases did not differ significantly between the 2 treatment groups, whereas BMFS was significantly longer in patients receiving OV.

Conclusions

OV plus trastuzumab yielded similar results in terms of PFS and RR and was superior in terms of OS and BMFS. These results add to the growing body of evidence that vinorelbine is a viable alternative to taxanes in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Keywords: Brain metastases, Metastatic breast cancer, HER2-positive breast cancer, Oral vinorelbine, Taxanes, Trastuzumab

Introduction

Vinorelbine (5’-noranhydrovinblastine) is a third-generation vinca alkaloid with anti-microtubule properties [1]. In a preclinical model, Pegram and co-workers suggested synergistic activity for the combination of vinorelbine and trastuzumab [2]. In vivo, the results of 2 randomized studies showed comparable activity of intravenous vinorelbine and taxanes in HER2-positive breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy plus trastuzumab, although 1 of these studies was discontinued prematurely due to poor recruitment [3, 4]. Both studies reported a consistent lower toxicity rate in the respective vinorelbine arms. Another potential advantage of vinorelbine is the availability of an oral formulation. Although oral vinorelbine (OV) in general provides similar activity as compared to standard intravenous vinorelbine, no direct comparison of OV to taxanes in combination with trastuzumab as first-line therapy of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer has yet been conducted (and is unlikely to be conducted in the future due to the introduction of novel HER2-targeted drugs) [5, 6]. Therefore, this retrospective chart review was initiated.

A high incidence of brain metastases (BMs) is an important issue with HER2-positive breast cancer [7, 8, 9]. Notably, an increased rate of BMs was reported in patients with prior taxane exposure [10]. This led us to investigate whether patients receiving OV as first therapy for HER2-positive metastatic disease had a lower risk of developing BMs or showed longer BM-free survival (BMFS).

Patients and Methods

Patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer treated with trastuzumab-based first-line chemo-immunotherapy from 2000 until 2010 were identified from a breast cancer database. Information relating to patient demographics, case history, and survival were collected by chart review. This retrospective analysis was conducted in accordance with the ethical regulations of the Medical University of Vienna and approval by the local ethics committee was obtained.

All patients were managed by a dedicated team of breast cancer specialists at an academic breast centre. The decision for treatment of HER2-positive metastatic disease with either taxanes or OV as first-line therapy was taken in an interdisciplinary tumour conference.

Treatment Plan and Patient Evaluation

Patients received taxanes (docetaxel 75–100 mg/m2 once every 3 weeks; docetaxel 35 mg/m2 weekly; paclitaxel 90 mg/m2 weekly for 3 weeks followed by 1 week of rest; or paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 once every 3 weeks) or OV (60 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of a 3-week cycle) as the chemotherapy backbone in combination with trastuzumab (4 mg/kg body weight loading dose followed by 2 mg/kg body weight weekly thereafter; or 8 mg/kg body weight loading dose followed by 6 mg/kg body weight every 3 weeks thereafter) [11].

At initiation of first-line trastuzumab treatment, all patients had computed tomography (CT) scans of chest and abdomen, a bone scan, echocardiography and gynaecological examination with further work-up if indicated. Response was assessed every 9 weeks using World Health Organisation (WHO) response criteria. CT scans were repeated every 9 weeks and echocardiography was routinely performed once every 3 months.

As this was a retrospective analysis, no central radiological re-assessment of response rates was possible. Still, in each individual patient, response was assessed at 1 single radiological institute, thereby assuring the comparability of radiological reports. No routine brain imaging as screening for central nervous system (CNS) involvement was performed and brain imaging was only done when clinically indicated due to neurological symptoms.

Due to the retrospective nature of this analysis, no reliable data concerning toxicity could be recorded. Dose reductions due to toxicity, on the other hand, were recorded and are provided in the results section. Moreover, data concerning cardiotoxicity are available due to routine echocardiographies, which were performed once every 3 months.

Hormone Receptor and HER2 Status

Oestrogen-receptor (ER) and progesterone-receptor (PgR) status was assessed by immunohistochemistry (ERα antibody, clone 1D5; PgR antibody; both from Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) on primary tumour material or on biopsy material from metastatic sites, whichever was available. Hormone receptor expression was estimated as the percentage of positively stained tumour cells. Results were given as 1+, 2+, and 3+ positive or negative staining, with a cut-off value of < 10% positive tumour cells [12]. HER2 status was assessed by immunohistochemistry (Herceptest®; Dako A/S) or dual colour fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH; PathVision® HER2 DNA probe kit, Vysis Inc., Downers Grove, IL, USA). Tumours were classified as HER2 positive if they had a staining intensity of 3+ on the Herceptest® scale; tumours with a staining intensity of 2+ were tested by FISH or chromogenic in situ hybridisation (CISH) for HER2 DNA amplification [13].

Study Endpoints

Progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time-interval between initiation of first-line trastuzumab-based chemo-immunotherapy and documented disease progression, was chosen as the primary study endpoint; secondary endpoints were overall survival (OS), response rate (RR), incidence of BMs and BMFS, which was defined as time interval from initiation of first-line trastuzumab treatment up until radiological diagnosis of symptomatic BMs.

Statistical Analysis

PFS, OS, and BMFS were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier product limit method. To test for differences between curves, the log-rank test was used. For correlation of 2 parameters, Fisher's exact test was used. 2-tailed p values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Variables exhibiting significance (p < 0.05) or near significance (p < 0.07) on univariate analysis of PFS, OS and BMFS were included into Cox proportional hazards models. All statistics were calculated using statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS®) 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Seventy-six consecutive patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who received taxanes or OV in combination with trastuzumab as first-line therapy were identified from a breast cancer database and included into this retrospective chart review. Data were analysed as of October 2012 at a median follow-up of 47.5 months from initiation of trastuzumab-based first-line chemo-immunotherapy.

Median patient age was 49.5 years (range, 28–83 years). Taxanes were administered as chemotherapy backbone in 36 (47.4%) of the 76 patients (group A), and 40 patients (52.6%) received OV (group B). Within group A, the majority of patients received docetaxel (n = 27; 75%).

Patient characteristics were similar between the 2 treatment groups (table 1). The only major disparities concerned age distribution (patients ≥ 65 years 0% vs. 22.5% in groups A and B, respectively; Fisher's exact test; p = 0.003) and prior exposure to taxanes in the adjuvant setting (8% vs. 28% in groups A and B, respectively; Fisher's exact test; p = 0.04). Characteristics of all 76 patients are provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (separated for groups A and B)

| Characteristics | Group A | Group B | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entered, n | 36 | 40 | |

| Median age at breast cancer diagnosis, years (range) | 45.5 (36–64) | 56 (28–83) | |

| Patients ≥ 65 years | – | 9 (22.5%) | 0.003 |

| Oestrogen receptor positive | 18 (50%) | 15 (37.5%) | n.s. |

| Her2-positive | 36 (100%) | 40 (100%) | – |

| Grading 3 | 26 (72.2%) | 32 (80%) | n.s. |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 27 (75%) | 33 (82.5%) | n.s. |

| Stage at primary diagnosis | |||

| Localized | 28 (77.8%) | 34 (85%) | n.s. |

| Metastatic | 8 (22.2%) | 6 (15%) | n.s. |

| Disease-free interval ≤ 24 months | 11 (30.5%) | 17 (42.5%) | n.s. |

| Visceral disease | 27 (75%) | 26 (65%) | n.s. |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 20 (55.6%) | 25 (62.5%) | n.s. |

| Adjuvant taxane-based chemotherapy | 3 (8.3%) | 11 (27.5%) | 0.04 |

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy | 17 (47.2%) | 13 (32.5%) | n.s. |

| Adjuvant trastuzumab | 3 (8.3%) | 5 (12.5%) | n.s |

| Palliative endocrine therapy before trastuzumab | 7 (19.4%) | 6 (15%) | n.s. |

Fisher's exact test.

n.s. = not significant.

Efficacy

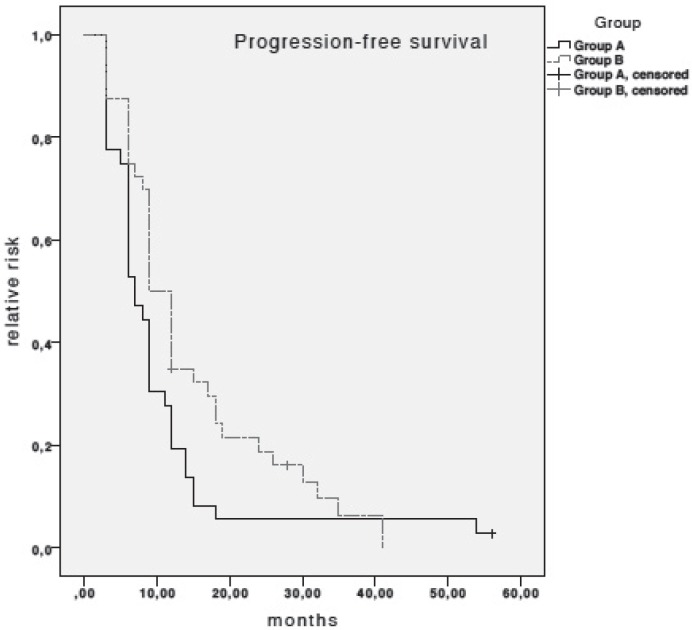

Median PFS in patients receiving taxanes plus trastuzumab was 7 months (95% confidence interval (CI), 5.4–8.6), as compared to 9 months (95% CI, 7.23–10.77) in patients treated with OV (log-rank test; non-significant (n.s.)) (fig. 1). None of the variables investigated on univariate analysis of PFS were associated with PFS. Therefore, no multivariate Cox regression modelling was performed.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for progression-free survival (PFS). Median PFS in patients receiving taxanes plus trastuzumab (group A) was 7 months (95% CI, 5.4–8.6) and 9 months (95% CI, 7.23–10.77) in patients receiving oral vinorelbine plus trastuzumab (log-rank test; n.s.).

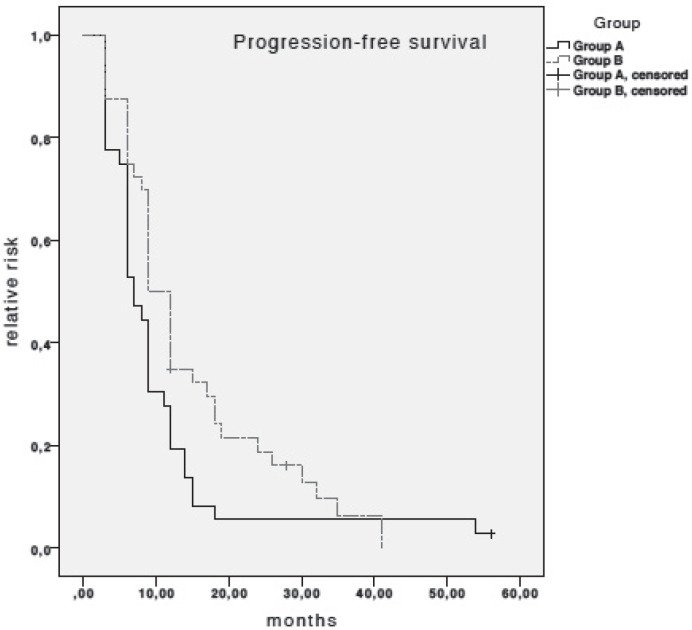

Median OS in patients receiving taxanes plus trastuzumab was 49 months (95% CI, 38.24–59.76), as compared to 59 months in patients receiving OV (95% CI, 41.17–76.83) (log-rank test; p = 0.033) (fig. 2). Again, none of the other variables were associated with OS on univariate analysis.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for overall survival (OS). Median OS in patients receiving taxanes plus trastuzumab (group A) was 49 months (95% CI, 38.24–59.76) and 59 months (95% CI, 41.17–76.83) in patients receiving oral vinorelbine plus trastuzumab (log-rank test; p = 0.033).

The combination of taxanes plus trastuzumab yielded a complete response (CR) in 1/36 patients (2.8%; 95% CI, 0.00–0.08); a partial response (PR) in 21/36 patients (58.3%; 95% CI, 0.42–0.74); and disease stabilization for a minimum of 6 months in 6/36 patients (16.7%; 95% CI, 0.05–0.29). For 8/36 patients disease progressed despite treatment (22.2%; 95% CI, 0.09–0.36). Respective numbers in patients receiving OV plus trastuzumab were 6/40 patients with CR (15%; 95%, CI 0.04–0.26); 19/40 patients with PR (47.5%; 95%, CI 0.32–0.63); 7/40 patients with stable disease (17.5%; 95% CI, 0.06–0.29); and 5/40 patients with disease progression (12.5%; 95% CI, 0.02–0.23). In 3 patients (7.5%), response was not evaluable due to the retrospective design of this analysis; however, no disease progression within 6 months was documented. Response rates, therefore, were similar between the 2 groups (61.1% group A vs. 62.5% group B; Fisher's exact test, n.s.) (table 2).

Table 2.

Response rates

| Response | Group A |

Group B |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| CR | 1 | 2.8 | 0.00–0.08 | 6 | 15 | 0.04–0.26 |

| PR | 21 | 58.3 | 0.42–0.74 | 19 | 47.5 | 0.32–0.63 |

| SD | 6 | 16.7 | 0.05–0.29 | 7 | 17.5 | 0.06–0.29 |

| PD | 8 | 22.2 | 0.09–0.36 | 5 | 12.5 | 0.02–0.23 |

| n.a. | – | – | – | 3 | 7.5 | 0.00–0.16 |

CI = 95% confidence interval, CR = complete response, PR = partial response, SD = stable disease, PD = progressive disease, n.a. = not available.

Dose reductions due to treatment-induced toxicity were frequently necessary in both treatment arms; not surprisingly, numerically higher rates were observed in patients receiving taxanes as chemotherapy backbone (11/36 patients (30.6%) vs. 6/40 patients (15%); Fisher's exact test; n.s.). No cases of symptomatic cardiac failure were observed; a significant drop of left-ventricular ejection fraction ≥ 10% (but not below 50%) was reported in a single patient within the taxane group.

Brain Metastases

Overall, 36/76 (47.4%) patients were diagnosed with symptomatic BMs during their course of disease. BMFS was significantly longer in patients receiving OV plus trastuzumab as compared to patients receiving taxanes plus trastuzumab as first-line therapy (69 months vs. 51 months; p = 0.032). Again, none of the other variables investigated were associated with BMFS. Median OS after diagnosis of BM was 9 months (95% CI, 5.5–12.5).

Discussion

In this study, we retrospectively compared clinical activity of taxanes plus trastuzumab (group A) to OV plus trastuzumab (group B) as first-line therapy in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients. We observed similar results in terms of PFS and RR with both chemotherapy backbones (PFS 7 vs. 9 months, RR 61.1% vs. 62.5% in groups A and B, respectively). Notably, OS and BMFS were significantly longer in the OV group; on the other hand, the overall incidence of BMs was comparable between the 2 groups (55.6% group A vs. 40% group B; n.s.).

Concerning activity of OV, comparison of our result to efficacy data from prospective randomized trials using intravenous vinorelbine is pertinent. Indeed, PFS compared well to data from the TRAVIOTA trial (PFS 8.5 months) [3]. Our results are also well in line with efficacy data of OV plus trastuzumab as first-line therapy in 2 smaller single-arm phase II studies and 1 phase II study with alternating administration of intravenous and OV plus trastuzumab [11, 14, 15]. Those data, therefore, strengthen the validity of our results despite the retrospective study design.

Superior OS was observed in patients receiving OV plus trastuzumab as compared to the taxane group (49 months in group A vs. 59 months in group B; p = 0.033). None of the other variables tested by univariate analysis were significantly associated with OS. There may be several explanations for the longer survival in patients receiving OV. First, lower toxicity rates associated with OV may have enabled patients to receive a higher overall number of palliative chemotherapy lines; however, this is apparently not the case as the median number of further treatment lines in both groups was the same. Secondly, OV became available in 2003; therefore, a large proportion of patients may have gone on to receive lapatinib in addition to trastuzumab as HER2-targeted therapy. Indeed, for the patients studied here, numerically more patients in group B were treated with lapatinib as compared to group A (10% vs. 0%; Fisher's exact test; n.s.). Thirdly, due to the retrospective design of this study, there were certain disparities between the 2 treatment groups. In the OV group, the number of patients with prior exposure to taxanes in the adjuvant setting was significantly higher (27.5% vs. 8.3%); furthermore 22.5% of patients in group B were ≥ 65 years. However, it would be expected that both of these factors would rather predict a worse outcome. We assume that the survival benefit associated with OV treatment is either due to later treatment initiation (from 2003 onwards), or is spurious and due to the overall small sample size and the retrospective design of this study.

Nearly a decade ago, an increasing rate of patients diagnosed with BMs was reported in HER2-positive breast cancer patients [7]. Notably, Crivellari and colleagues observed a higher incidence of BMs in patients receiving docetaxel-based first-line chemotherapy for metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer [10]. This observation is strengthened by preclinical data suggesting a higher incidence of BMs after prior taxane exposure in a mouse model [16]. In our study, however, we could not establish a significantly lower incidence of BMs in the OV group. On the other hand, BMFS was significantly longer in patients receiving OV (69 vs. 59 months; p = 0.032). These data are intriguing and re-evaluation of this issue in a larger patient sample therefore appears warranted.

Median OS after diagnosis of BMs was 9 months (95% CI, 5.5–12.5). Results are, therefore, well in line with data from other recent studies and once again highlight the relatively good prognosis of HER2-positive breast cancer patients even after diagnosis of BMs. [9] This fact clearly renders a nihilistic approach to BMs as obsolete in an HER2-positive breast cancer population.

Obviously, our study has several limitations: a small overall patient number, a retrospective design, the long observation period leading to different taxane-based treatment regimens, and the lack of central radiological assessment as well as the lack of toxicity data. On the other hand, this is the first study to directly compare the activity of taxanes to OV as chemotherapy backbone. Despite the clear limitations, we therefore believe that this study adds information to the field of metastatic breast cancer management.

In conclusion, we suggest that despite the retrospective design of this study, our data add to the growing body of evidence that vinorelbine is indeed a viable alternative to taxanes as chemotherapy backbone for trastuzumab-containing chemo-immunotherapy. In light of those results, further evaluation of OV in combination with novel HER2-targeted therapies appears warranted.

Disclosure Statement

Rupert Bartsch and Matthias Preusser have received lecture honoraria, travel support and research support from Roche Austria.

Acknowledgments

The costs for this project were covered by the research budget of the Medical University of Vienna. Apart from the authors, the following persons contributed to this study: Gabriela Altorjai, Gudrun Boeckmann, and Ursula Pluschnig.

References

- 1.Potier P. The synthesis of navelbine prototype of a new series of vinblastine derivatives. Semin Oncol. 1989;16:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pegram MD, Lopez A, Konecny G, Slamon DJ. Trastuzumab and chemotherapeutics: Drug interactions and synergies. Semin Oncol, discussion 92-100. 2000;27:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burstein HJ, Keshaviah A, Baron AD, et al. Trastuzumab plus vinorelbine or taxane chemotherapy for HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer: The trastuzumab and vinorelbine or taxane study. Cancer. 2007;110:965–972. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson M, Lidbrink E, Bjerre K, et al. Phase III randomized study comparing docetaxel plus trastuzumab with vinorelbine plus trastuzumab as first-line therapy of metastatic or locally advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: The hernata study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:264–271. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baselga J, Cortes J, Kim SB, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109–119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1783–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin NU, Winer EP. Brain metastases: The HER2 paradigm. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1648–1655. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanna G, Franceschelli L, Rotmensz N, et al. Brain metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:2865–2869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berghoff A, Bago-Horvath Z, De Vries C, et al. Brain metastases free survival differs between breast cancer subtypes. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:440–446. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crivellari D, Pagani O, Veronesi A, et al. High incidence of central nervous system involvement in patients with metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer treated with epirubicin and docetaxel. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:353–356. doi: 10.1023/a:1011132609055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartsch R, Wenzel C, Altorjai G, et al. Results from an observational trial with oral vinorelbine and trastuzumab in advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:375–381. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2784–2795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catania C, Medici M, Magni E, et al. Optimizing clinical care of patients with metastatic breast cancer: A new oral vinorelbine plus trastuzumab combination. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1969–1975. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinemann V, Di Gioia D, Vehling-Kaiser U, et al. A prospective multicenter phase II study of oral and i.v. vinorelbine plus trastuzumab as first-line therapy in HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:603–608. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mischo A, Harter P, Müller K, et al. Docetaxel pretreatment is associated with increased incidence of CNS-metastases in a murine model of HER2-positive breast cancer. Onkologie. 2012;35:64S–Abstr.214. [Google Scholar]