Abstract

The hypothesis that the disinhibitory effects induced by alcohol consumption contribute to domestic violence has gained support from meta-analyses of mainly cross-sectional studies that examined the association between alcohol abuse and perpetration of intimate partner violence (IPV). However, findings from multilevel analyses of longitudinal data investigating the time-varying effects of heavy episodic drinking (HED) on physical IPV have been equivocal. This 12-year prospective study used multilevel analysis to examine the effects of HED and illicit drug use on perpetration of both physical and psychological IPV during early adulthood. Participants were 157 romantic couples who were assessed biennially 2 to 6 times for substance misuse and IPV. The analyses found no significant main effect of either HED or drug use on perpetration of IPV but there were significant interactions of both HED and drug use with age. Moreover, the developmental trends in substance use effects on IPV typically varied by gender and type of IPV.

Keywords: drug abuse, aggression, alcohol, dependence, drugs, intimate partner violence

The prevalent belief that misuse of psychoactive substances contributes to domestic violence received initial credence from observations made in a law enforcement context. For example, a study of police visits to domestic violence scenes found that 92% of perpetrators had used alcohol or other drugs on the day of the incident (Brookoff, O'Brien, Cook, Thompson, & Williams, 1997). Similar findings relating the use of substances, especially alcohol, to assaults have been reported in diverse samples (Abbey, 2002; Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1998; Kaufman Kantor, & Strauss, 1990; see review by Fals-Stewart, Klostermann, & Clinton-Sherrod, 2009).

Accordingly, numerous studies—using different kinds of samples, theoretical orientations, and methodologies—have examined the association between substance abuse and perpetration of intimate partner violence (IPV). The most common approach entails examination of correlations or mean differences to determine whether substance abusers commit more IPV than those who do not abuse substances. For example, Feingold, Kerr, and Capaldi (2008) compared IPV scores between at-risk men who were and were not dependent on each of a number of substances and found larger means for men dependent on alcohol and most illicit substances than for their nondependent peers. This paradigm continues to be widely used (e.g., Mattson, O'Farrell, Lofgreen, Cunningham, & Murphy, 2012; Smith, Homish, Leonard, & Cornelius, 2012), and meta-analyses of findings in the now extensive literature have documented significant positive associations of IPV with abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs for both men and women (Foran & O'Leary, 2008; Moore, Stuart, Meehan, Rhatigan, Hellmuth, & Keen,, 2008; Rothman, Reyes, Johnson, & LaValley, 2012). Substance abuse has also been identified as a correlate of aggression in a recent qualitative review of risk factors for IPV perpetration (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012).

Most of the studies included in these reviews have been cross-sectional. That is, all participants were measured on both substance abuse and IPV at a single time. A newly emerging line of work, by contrast, uses multilevel analysis (such as hierarchical linear models; Feingold, 2009; 2013; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) of data regularly collected on both substance abuse and IPV to determine the time-varying associations between the two variables over the course of the study. Instead of examining whether people who abuse substances commit more IPV than do nonabusers, multilevel analysis addresses a different question: Does onset of or desistance from substance abuse increase or decrease the likelihood that an individual will commit IPV? If the answer is yes, then that would mean that substance abuse and IPV perpetration would most often occur in the same year.

Surprisingly, neither of the two studies that used this newer approach found an unqualified time-varying association between alcohol use, as measured only by heavy episodic drinking (HED), and physical IPV perpetration in adulthood (Reyes, Foshee, Bauer, & Ennett, 2011; Schumacher, Homish, Leonard, Quigley, & Kearns-Bodkin, 2008). What might explain the discrepancy between the meta-analytic and multilevel results about the linkage between HED and IPV? Two factors need to be considered. First, the meta-analysis of studies of the associations of IPV with alcohol misuse (Foran & O'Leary, 2008) combined findings from clinical and community samples, whereas the two multilevel analysis studies were both conducted with community samples. Foran and O'Leary's meta-analysis found that mean effect size was significantly larger in clinical samples (e.g., where generally calculated by comparing mean IPV scores from IPV perpetrators with “controls”) than in community samples (which typically correlated the two variables in a single group), noting an average correlation of only .19 between alcohol and IPV perpetration in community samples of men. Given that the same meta-analysis also found smaller effect sizes for women than for men, the corresponding correlation in mixed-sex community samples (such as those used in the multilevel studies) would be expected to be even smaller and thus difficult to detect because of low power.

Second, multilevel analysis helps control for confounds related to individual differences by examining intraindividual associations across time. Third party variables could be associated with both alcohol use and IPV perpetration in adulthood, which would inflate the magnitude of an observed association of alcohol abuse with IPV in cross-sectional analyses, and could even result in a finding of a wholly spurious relationship between the two variables (Gelles & Cavanaugh, 2005; Leonard & Quigley, 1999). For example, Feingold et al. (2008) found alcohol dependence to be associated with IPV perpetration but the association was not significant after holding constant antisocial behavior (a trait that might be controlled for in multilevel analysis because it uses subjects as their own controls).

Therefore, the differences between findings from the meta-analytic and multilevel studies may be more apparent than real, as results from both paradigms indicated that the association between alcohol abuse and IPV explains little of the variance in the latter, particularly after considering the effects of extraneous variables in cross-sectional analyses. Why then have the observed overall effects of alcohol on IPV been weak or nil given the common belief--supported by experimental evidence (Giancola, Gadlaski, & Roth, 2012; Leonard, 2005)--that the disinhibitory effects of alcohol use is an important contributor to IPV perpetration (Arseneault, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, & Silva, 2000; Chermack & Taylor, 1995; Critchlow, 1983; Flanzer, 2005)?

Although the initial hypothesis was that excessive alcohol use increased perpetration of aggression for every imbiber, the current thinking posits a moderation model of the proximal effects of alcohol on aggression. Specifically, only certain types of people (particularly hostile people) are seen as likely to commit greater aggression when drinking than when not inebriated (see review by Fals-Stewart et al., 2009). If the effect exists only for a small subsample of the population, then the overall alcohol-IPV association would be small and hard to detect in an entire heterogeneous group of respondents, such as a community sample. The multilevel analysis by Schumacher et al. (2008) provided support for the moderation model, as it found a time-varying effect of HED on IPV only for a hostile individuals engaging in avoidant coping.

An important limitation of the recent multilevel analysis studies of the time-varying associations of substance abuse on IPV perpetration is that only alcohol behavior (e.g., HED) was used as a substance abuse outcome. Yet, drug abuse also has been found to predict IPV perpetration and that association remains significant even after controlling for alcohol abuse (Moore et al., 2008). Indeed, Feingold et al. (2008) found that controlling for antisocial behavior eliminated the statistical significance of the association between alcohol dependence and IPV but not of the relationship between drug dependence and IPV. Thus, unlike with alcohol, effects of drug abuse on IPV may not be limited to a small subpopulation of abusers.

The current 12-year prospective study of romantic couples recruited for the Oregon Youth Study (OYS; Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Kim, Laurent, Capaldi, & Feingold, 2008; Shortt, Capaldi, Kim, Kerr, Owen, & Feingold, 2012) uses multilevel analysis to examine the time-varying effects of both alcohol and drug use on IPV perpetration. It extends prior multilevel work by (a) examining data collected in early adulthood, (b) including drug use as an additional substance use covariate, and (c) including psychological IPV as an additional IPV outcome. We expected to replicate past findings of an absence of an overall association (i.e., a main effect) between HED and physical IPV but sought to determine whether this finding would generalize to drug use and physical IPV, and to the linkage between each type of substance abuse and psychological IPV.

Method

Participants

Participants were male-female couples consisting of 157 OYS men and one of their long-term romantic partners who completed the assessments with them (n = 314). Starting in late adolescence, the OYS men were invited to participate biannually with a current romantic partner in each 2-year assessment window. At Time 2 (T2) of the Couples Study—when the men were aged 20 years—the measures of IPV used in this study were first administered. Therefore, the current analyses used data from six consecutive waves of assessment of couples who were generally in the 20s to early 30s throughout the course of the study. Because this study is concerned with the effects of HED and drug use on IPV in early adulthood, dyadic data were included only when the men's partners were aged 17-38 years at time of assessment, although most partners were similar in age to the OYS men.

As most of the men did not bring the same partner to the different assessments, however, only data from each OYS man and his most participating partner—the partner of appropriate age who attended the largest number of Couples Study waves—were used in the analyses. (When their were “ties,” as when a man had participated twice with each of two different partners, the designated partner was the woman with the largest time period between her initial and final participation.) Finally, as the study examines changes over time, OYS men who never participated at least twice with the same partner at usable (i.e., within appropriate age ranges) ages were excluded.

On average, there were four time points of usable data from the 157 couples, with the numbers of couples who participated 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 times being 39, 29, 24, 26, and 39, respectively. The numbers of couples contributing data at each time were 67, 104, 121, 122, 115, and 96 at T2, T3, T4, T5, and T6, respectively. The mean ages of the men and their partners at final participation were 30.3 (SD = 2.6) and 28.8 (SD = 3.9), respectively. Two thirds of the couples were married at that time, and both partners in 80% of the couples were White.

Procedure

Assessments took about two hours to complete and included interviews (from which substance use was assessed) and questionnaires. At each assessment, men and women forming each couple attended at the same time but were interviewed separately. An interviewer traveled to assess the participants living outside the local area. All participants were monetarily compensated for their contributions.

Measurements

Heavy episodic drinking

HED was a binary time-varying covariate assessed with self-reports of number of drinks typically consumed at a single sitting and of the frequency of such drinking in the past year. Drinking monthly (or more frequently) and typically consuming five or more (for men) or four or more (for the women) drinks at a time was used because the five/four rule is frequently used to define HED (Jackson, 2008; Wechsler & Nelson, 2001).

Drug use

At each time point, both members of every couple reported their usage during the previous year of illicit substances associated with substance use disorders in the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The dichotomous time-varying drug use covariate was defined by a score of “1” for use of at least one illicit substance (including marijuana) and a score of “0” for abstinence from all such substances.

Intimate partner violence perpetration

IPV perpetrated in the past year was assessed by the physical and psychological aggression subscores of the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS; Straus, 1979), a questionnaire measure using a Likert scale on which respondents report the IPV they perpetrated on their current partner (and/or the IPV their current partner perpetrated on them) over the past year. The CTS physical aggression scale administered consisted of six items and the psychological aggression scale consisted of five items.

Both members of each couple completed the CTS twice at every time point—once to report their own perpetration of physical and psychological IPV to their partner and a second time to report their partners' IPV against them. Ratings for each participant's physical aggression perpetration were summed across type of reporter and item, and scores greater than “1” were recoded to “1” to create a binary variable for perpetration of physical IPV in the preceding year. Psychological IPV was the standardized log-transformed CTS psychological aggression perpetration score (average of self and partner reports). Across time and type of respondent, coefficient alphas for psychological IPV were .71 to .85 (mdn = .79) for men and .66 to .85 (mdn = .77) for women.

Data Analysis

The data were examined using three-level multilevel models in which repeated measures of IPV across time/ages (Level 1) were nested within individuals (Level 2) who were nested within couples (Level 3). All covariates were grand-mean centered to reduce multicollinearity (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Log-transformed psychological IPV scores had an approximately normal distribution for both sexes and were examined by methods of multilevel analysis for continuous outcomes (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

The reason physical IPV scores were dichotomized was because a large majority of the scores in the distribution were zero, thus violating the assumption of normality required for a standard multilevel analysis of continuous data. Zero-inflated distributions are commonly observed when psychopathological behaviors are assessed in community samples because most “normal” participants never display any of them (Atkins & Gallop, 2007). Our approach—examining binary physical IPV outcomes with analyses that used logits to model probabilities instead of scores (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002)—is identical to the first stage in two-part growth modeling (e.g., Olsen & Schafer, 2001). Two-part modeling was developed to handle longitudinal data with distributions, such as ours, characterized by a preponderance of zeros. However, there were not enough nonzero values for physical IPV in this study to warrant modeling them in a separate analysis (stage two).

Multilevel Analysis

The first set of analyses included HED alone as the substance abuse covariate. We began by fitting a separate quadratic growth model for HED for each type of IPV that included two time-invariant (Level 2 and Level 3) and three time-varying (Level 1) covariates. The Level 2 covariate was gender. The Level 3 covariate was relationship length at time of couples' last participation, which was included as a control variable. The time-varying Level 1 covariates included age, age‐squared (quadratic), and HED. All interactions among covariates (excluding interactions involving relationship status) were initially included in each model. However, nonsignificant higher-order interactions were removed in the last stage of model selection to yield the final reported models.

For each type of IPV, the quadratic model was compared with the deviance statistic to a linear model that deleted the four quadratic terms to determine whether nonlinear growth trajectory parameters were needed. The linear models were selected when deleting the quadratic terms did not significantly decrease model fit.

The next analysis began by adding drug use to the quadratic models for HED to test if the covariate's inclusion significantly improved prediction of perpetration of each type of IPV. The full combined substances models included relationship length as well as both drug use (a main effect) and the interactions of drug use with the covariates from the prior quadratic model (i.e., gender, HED, age, and age squared). Again, these quadratic models were compared with deviance statistics to respective linear models that deleted the eight quadratic terms to determine whether nonlinear growth trajectory parameters were needed. Findings from the linear combined substances models were reported when deleting the quadratic terms did not significantly decrease model fit.

Thus, multilevel models were used to determine whether respondents had a higher probability of perpetrating physical IPV—or displayed higher levels of psychological IPV—during the years when they had engaged in or used drugs than in years when they had not, and whether substance use effects on IPV were moderated by age or gender. Thus, the effects of changes in HED by itself (i.e., ignoring drug use) and the joint effects of HED and drug use on changes in IPV over the course of the study were both investigated.

Effect Sizes for Substance Use Effects

Because physical IPV perpetration was a dichotomous outcome variable that modeled logits, the typical effect size reported for such analysis is the odds ratio (Fleiss & Berlin, 2009). However, odds ratios can be converted to mathematically equivalent ds (Haddock, Rindskopf, & Shadish, 1998). Such conversions of odds ratios to ds were used by Moore et al. (2008) because they are useful in allowing for comparisons of results across outcomes with different distributions, as in meta-analysis, but also with physical and psychological IPV in the current study. Thus, d was used as the effect size to express both HED and drug use time-varying effects on both types of IPV, and ds were plotted as a function of age when these effects were found to vary significantly by age.

Results

Characteristics of Sample

Table 1 reports the proportions of participants, by gender and time point, who had drank heavily, used illicit drugs, perpetrated any physical IPV, and perpetrated any psychological IPV. The table shows consistent decreases across the times in each of these behaviors, with the exception of any perpetration of any psychological IPV (which is presented for completeness but not used in the multilevel analyses).

Table 1. Proportions of Participants Perpetrating Intimate Partner Violence and Using Substances in Past Year.

| Substance Use | Intimate Partner Violence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Heavy Episodic Drinking | Drug Use | Physical | Psychological | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Time | M | W | M | W | M | W | M | W |

| 2 | .34 | .18 | .51 | .40 | .37 | .43 | .88 | .90 |

| 3 | .26 | .11 | .50 | .43 | .25 | .24 | .87 | .91 |

| 4 | .22 | .10 | .43 | .45 | .21 | .21 | .90 | .93 |

| 5 | .21 | .13 | .41 | .37 | .16 | .16 | .89 | .90 |

| 6 | .09 | .05 | .40 | .27 | .17 | .15 | .88 | .88 |

| 7 | .13 | .09 | .33 | .25 | .07 | .11 | .87 | .89 |

Note. M = Men, W = Women.

Physical Aggression

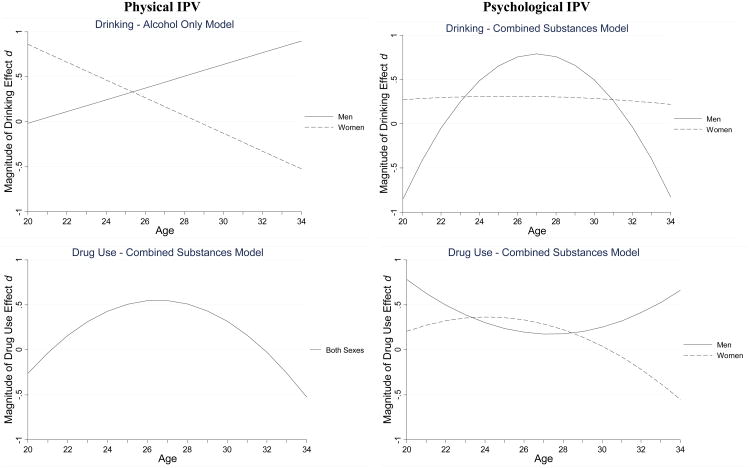

The linear model for HED best fit the data for perpetration of physical IPV and the Gender × HED × Age Interaction was statistically significant (b = -.30, p < .05). As shown in the top left panel of Figure 1, the ds for the men increased across ages, indicating an increasing positive effect of HED on physical IPV. For women, age was also a strong moderator of the HED effect, which was found to be positive only in the early 20s. Thus, for both sexes, whether or not engaging in HED over the past year increases the probability of perpetrating IPV during that year varied by age. Moreover, these age-related changes in effects were different for men than for women.

Figure 1. Age-Related Trends in Effects of Drinking (Heavy Episodic Drinking) and Drug Use on Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence.

When drug use (including cross-products for its interactions with other covariates) was entered into the equation in the combined substances (HED plus drug use) models, the quadratic model better fit the data than did the linear model. The three-way interaction involving HED was not statistically significant and the other effects involving HED also were nonsignificant (ps > .10) in this model. To make the comparison between the alcohol-only model and the combined-substances model more meaningful, we also examined a linear model, which has been used for the alcohol-only HLM. The HED × Gender × Age interaction on physical IPV was also nonsignificant (p > .10) in the linear model. These findings confirmed our prediction that effects of HED on IPV would not be statistically significant after controlling for drug use.

The effects of drug use on physical IPV perpetration in this model varied nonlinearly with age, as the Drug Use × Age-Squared (Quadratic) Interaction was significant (b = -.03, p < .05). As shown in the bottom left panel of Figure 1, drug use was a positive predictor of physical IPV perpetration (after controlling for HED) only when participants were in their mid-20s.

Psychological Aggression

When HED was the only substance use variable entered (including the cross-products for the interactions of HED with other covariates) in the model, the effects of HED on psychological IPV varied nonlinearly with age and gender. The Gender × HED × Age-Squared (Quadratic) interaction was statistically significant (b = .01, p < .05) and remained so in the final (combined substances) model that also included (and thus controlled for) drug use (b = .02, p < .01). As shown by the curves of ds plotted in the top right panel of Figure 1 for the final (combined substances) model, a positive quadratic association between the HED effect and age was found for the men. The expected positive effect of men's HED only emerged at the middle of the age distribution. For women, by contrast, there was a relatively constant association between the HED effects (ds) and age (after controlling for drug use). A positive effect of women's HED on their perpetration of psychological IPV was found consistently across the ages examined.

The effect of drug use on psychological IPV in the final (combined substances) model also varied nonlinearly with age and group, as the Gender × Drug Use × Age-Squared (Quadratic Slope) interaction was significant (b = .01, p < .05). The expected positive effect of drug use on psychological IPV for the men was notable only when the men were in their early 20s and early 30s (see bottom right panel in Figure 1). For women, the effect was found only when they were in their early to mid-20s. Thus, the effects of drug use on psychological IPV differed from its effects on physical IPV in that gender was a moderator only for psychological IPV.

Discussion

The current study is one of the few investigations to have applied growth modeling (multilevel) analysis to repeated measures of IPV as outcomes and substance use measures as time-varying covariates. Consistent with predictions based on findings from two previous multilevel studies (Schumacher et al., 2008; Reyes et al., 2011), the main effect of HED on physical IPV perpetration was not statistically significant. Thus, the participants with a history of HED were, on the average (i.e., combined across ages and genders), no more likely to have aggressed against their partners during years when they engaged in HED than during years when they had not. The current study extended prior work by finding that the absence of a main effect of HED on IPV generalized to psychological IPV.

Also consistent with findings from two previous multilevel analysis studies, the absence of a main effect of HED on perpetration of physical IPV was qualified by the presence of significant interactions. Specifically, three-way interactions involving substance abuse, gender, and age on perpetration of both physical and psychological IPV were observed. The findings of interaction rather than main effects of HED on IPV might best be explained by the alcohol myopia hypothesis, which posits that effects of alcohol on social behavior model are based on perception of environmental cues (see review by Steele & Joseph, 1990) that will likely vary across gender and age, and that the proximal effects of alcohol can sometimes engender more rather than less prudent (e.g., less aggressive) behavior (e.g., MacDonald, Fong, Zanna, & Martineau, 2000). This model would thus predict interactive rather than main effects because of moderation by perception of environmental cues, whereas other models of alcohol's effects on IPV would predict main effects. However, this model has never been previously applied to explaining effects of alcohol use on IPV.

A unique contribution of the current multilevel analysis was to examine the time-varying effects of past-year drug use on IPV after controlling for HED. As with HED, there were no significant main effects of drug use on physical or psychological IPV. However, there were quadratic effects of age that interacted with drug use in affecting IPV. When physical IPV was the outcome, the quadratic trend of the effects of drug use was the same for men and women (with a positive effect observed only when participants were in their mid-20s). However, a three-way interaction was observed for psychological IPV, as the quadratic trend involving drug use was different for the men than for the women. Thus, drug use did affect the probability of perpetration of IPV overall but whether that probability increased or decreased at any given time varied with age and/or sex.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the present study that need to be considered. First, the absence of measures of hostility for both sexes prevented us from attempting to replicate the finding by Schumacher et al. (2008) and others using different that certain types of hostile individuals were more likely to perpetrate IPV during periods when they engaged in HED. It would have particularly valuable to have been able to examine whether such moderation effects generalized to drug use.

Also, the alcohol and drug use covariates were limited to frequency measures rather than measures of substance-related problems (including symptoms of dependence). Although alcohol abuse includes both HED and alcohol dependence, our study examined only effects of HED because the OYS data set did not include time-varying measures of alcohol dependence that could be used as a time-varying covariate in the multilevel analyses. Although the measurement of HED measure with a binary variable is well established in the alcohol literature (e.g., Sher, Jackson, & Steinley, 2011), the use of frequency data regarding illicit drugs was more problematic. Unlike for alcohol, where moderate use is not considered harmful, any use of illicit drugs is viewed as problematic. Therefore, drug abuse researchers often focus on abstinence as the critical outcome. Thus, the current study examined use versus abstinence from illicit drugs as the second covariate. However, such dichotomization precludes a distinction between those who regularly use and abuse drugs with those who, for example, only use marijuana once or twice a year and have no substance abuse problem. The occasional marijuana user would probably not be more likely to perpetrate IPV than participants who never use drugs (and with whom they might be more appropriately grouped). Yet, in spite of the limitations of the drug use measure, drug use was found to predict IPV, even after controlling for HED, but only via its interactions with demographic factors. Moreover, inclusion of drug use in the models removed the significance of all interactive effects involving HED on physical IPV, which could be due to shared variance of HED and drug use on IPV perpetration.

The study used the original CTS to measure IPV rather than its revision (the CTS2; Straus, Hamb, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) because only the CTS was available at the start of this prospective study. Thus, a final limitation is that we could not measure the effects of HED and drug use on measures later added to the CTS, particularly of sexual violence.

Conclusions

In summary, the current multilevel analyses found that people who engaged in HEV and/or used drugs at some times during the course of our longitudinal study did not commit more IPV during those years than at times when they were not using drugs or drinking heaviy than in years when they were not doing so,. Thus, a reduction in HED--or achieving abstinence from drug use--may have little or no effect on the risk of physical victimization for the user's partner at a given time because the associations of perpetration of IPV were found to be moderated by age and gender, and were as often in the opposite direction as in the expected direction.

Future research is needed that examines the time-varying effects of alcohol and drug dependence on IPV, as all the multilevel studies have failed to include dependence as a time-varying covariate. In addition, future multilevel research should consider victimization, which has been widely used in cross-sectional research associating substance abuse with IPV (e.g., Feingold & Capaldi, in press), as a time-varying IPV outcome.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of Drug Abuse (RC1DA028344), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA018669), and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD46364). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

References

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl):118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th. Washington DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor PJ, Silva PA. Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:979–986. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:726–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett ME, McCrady BS, Johnson V, Pandina RJ. Problem drinking from young adulthood to adulthood: Patterns, predictors, and outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:605–614. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookoff D, O'Brien KK, Cook CS, Thompson TD, Williams C. Characteristics of participants in domestic violence: Assessment at the scene of domestic assaults. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:1369–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Alcohol and crime: An analysis of national data on the prevalence of alcohol involvement in crime (Report No NCJ 168632) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1175–1188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermack ST, Taylor SP. Alcohol and human physical aggression: Pharmacological versus expectancy effects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:449–456. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral analysis. 3rd. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Critchlow B. Blaming the booze: The attribution of responsibility for drunken behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1983;9:451–473. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Klostermann K, Clinton-Sherrod M. Substance abuse and intimate partner violence. In: O'Leary KD, Woodin EM, editors. Psychological and physical aggression in couples: Causes and interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychological Methods. 2009;14:43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. A regression framework for effect size assessments in longitudinal modeling of group differences. Review of General Psychology. 2013;17:111–121. doi: 10.1037/a0030048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Capaldi DM. Associations of women's substance dependency symptoms with intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.5.2.152. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Kerr DCR, Capaldi DM. Associations of substance use problems with intimate partner violence for at-risk men in long-term relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:429–438. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanzer JP. Alcohol and other drugs are key causal agents of violence. In: Loseke DR, Gelles RJ, Cavanaugh MM, editors. Current controversies on family violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL, Berlin JA. Effect sizes for dichotomous data. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. 2nd. New York: Russell Sage; 2009. pp. 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O'Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ, Cavanaugh MM. Association is not causation: Alcohol and other drugs do not cause violence. In: Loseke DR, Gelles RJ, Cavanaugh MM, editors. Current controversies on family violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Gadlaski AJ, Roth RM. Identifying component-processes of executive functioning that serve as risk factors for the alcohol-aggression relation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:201–211. doi: 10.1037/a0025207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock CK, Rindskopf D, Shadish WR. Using odds ratios as effect sizes for meta-analysis of dichotomous data: A primer on methods and issues. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM. Heavy episodic drinking: Determining the predictive utility of five or more drinks. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:68–77. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman Kantor G, Straus MA. The “drunken bum” theory of wife beating. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990. pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Laurent HK, Capaldi DM, Feingold A. Men's aggression toward women: A 10-year panel study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1169–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: When can we say that heavy drinking is a contributing cause of violence? Addiction. 2005;100:422–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Drinking and marital aggression in newlyweds: An event-based analysis of drinking and the occurrence of husband marital aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;67:537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, Fong GT, Zanna MF, Martineau AM. Alcohol myopia and condom use: Can alcohol intoxication be associated with more prudent behavior? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:605–619. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson RE, O'Farrell TJ, Lofgreen AM, Cunningham K, Murphy CM. The role of illicit substance use in a conceptual model of intimate partner violence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:255–264. doi: 10.1037/a0025030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Rhatigan DL, Hellmuth JC, Keen SM. Drug abuse and aggression between intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:247–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen MK, Schafer JL. A two-part random-effects model for semicontinuous longitudinal data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:730–745. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Orderly change in a stable world: The antisocial trait as a chimera. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:911–919. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Bauer DJ, Ennett ST. The role of heavy alcohol use in the developmental process of desistance in dating aggression during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9456-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Reyes LM, Johnson RM, LaValley M. Does the alcohol make them do it? Dating violence perpetration and drinking among youth. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2012;34:103–119. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Quigley BM, Kearns-Bodkin JN. Longitudinal moderators of the relationship between excessive drinking and intimate partner violence in the early years of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Jackson KM, Steinley D. Alcohol use trajectories and the ubiquitous cat's cradle: Cause for concern? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(2):322–335. doi: 10.1037/a0021813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortt JW, Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Kerr DCR, Owen LD, Feingold A. Stability of intimate partner violence by men across 12 years in young adulthood: Effects of relationship transitions. Prevention Science. 2012;13:360–369. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0202-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Intimate partner violence and specific substance use disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:236–245. doi: 10.1037/a0024855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Joseph RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. Binge drinking and the American college student: What's five drinks? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:287–291. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]