Abstract

Background

Gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) rates were confirmed across different DSM editions as well as the role of bipolar disorder (BD) comorbidity on prevalence and course, but little data is available upon new DSM-5 criteria, including maladaptive behaviors. The aim of this study was to investigate gender differences in DSM-5 PTSD in a sample of young adult earthquake survivors and the impact of lifetime mood spectrum comorbidity.

Methods

Five hundred twelve young adult survivors from the L’Aquila 2009 earthquake were evaluated by Trauma and Loss Spectrum-Self Report (TALS-SR) and Mood Spectrum-Self Report (MOODS-SR).

Results

Females showed significantly higher DSM-5 PTSD prevalence rates than men. Similarly, female survivors with DSM-5 PTSD showed significantly higher scores in several of the MOODS-SR and TALS-SR domains with respect to males. Males showed significantly higher scores in the TALS-SR maladaptive coping domain only. A significant positive association between the MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and TALS-SR potentially traumatic events and maladaptive coping domains emerged in the whole sample, particularly among men.

Conclusion

This study allows a first glimpse on gender differences in DSM-5 PTSD criteria in a sample of earthquake survivors. Further, possible correlations with subthreshold manic-hypomanic comorbidity are suggested among males, showing a significant trend particularly for lifetime trauma exposure and for the newly introduced maladaptive behaviors.

Keywords: Trauma, Risk-taking behaviors, maladaptive behaviors, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Bipolar Disorder

Background

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a highly debilitating disorder that represents one of the most frequent consequences of the exposure to mass trauma, particularly earthquakes [1-10].

Since its first appearance in the DSM-III [11], PTSD diagnostic criteria have been changed across the subsequent editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), accordingly to increasing clinical and research findings in different populations. The last edition of the DSM (DSM-5) [12], just published in May 2013, introduced some important changes for what concern PTSD diagnosis. Besides defining a four-symptom cluster structure, instead of the DSM-IV-TR three one [13], the DSM-5 introduced three new symptoms: “persistent, distorted cognitions about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event(s) that lead the individual to blame himself/herself or others” (D3) and “persistent negative emotional state (e.g., fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame)” (D4), added in criterion D, exploring negative alterations in cognition and mood; “reckless or self-destructive behavior” (E2), added in criterion E, addressing symptoms of hyper-arousal. The introduction of this latest symptom, in particular, is related to the increasing evidence emerged in the last decades on the role of maladaptive behaviors in PTSD.

Maladaptive behaviors have been defined as volitional behaviors whose outcome is uncertain and which entail negative consequences that impact everyday activities [14-18]. The role of these behaviors in PTSD patients, like risk-taking behaviors, dangerous driving, or promiscuous sex, is evidenced by an increasing amount of literature [7,19-23]. Significantly higher rates of aggressive traits, including violent behaviors were found in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans with PTSD, compared to those without PTSD [24,25]. Male veterans also showed aggressive and unsafe driving [26,27]. Even the medication non-adherence rate resulted higher in veterans with PTSD with respect to those without [28]. Adolescents and young adults with PTSD due to terrorism, fire, or violence, showed risk-taking behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol and substance use, car racing, weapon carrying, violence, and delinquency. Some studies reported higher rates of maladaptive behaviors in victims with PTSD compared to non-affected subjects, with boys reporting significantly higher rates than girls [29-32].

In a previous study on young adult survivors of the 2009 earthquake that stroke the town of L’Aquila (Richter magnitude 6.3), causing 309 deaths, with about 1.600 injured individuals and 66.000 displaced, some of us reported significantly higher maladaptive coping prevalence rates among subjects with DSM-IV-TR PTSD, particularly males [18]. In a recent study [10], we further confirmed relevant rates of endorsement of the new E2 symptom among PTSD L’Aquila survivors diagnosed accordingly to DSM-5 criteria. In both studies, maladaptive behaviors had been explored by means of a spectrum approach to PTSD that explores a broad array of symptoms related to the Axis I disorder, including behaviors and personal characteristics that might represent manifestations and/or risk factors for the development of a stress response syndrome that also address these recently introduced criterion symptoms [9,10].

Several authors have recently indicated the relationship between PTSD and bipolar disorders (BD). BD patients demonstrated to be at higher risk for trauma exposure [33-37] and, when exposed, to be more vulnerable to developing PTSD. Rates of trauma exposure as high as 98% were reported in BD patients, compared to 51%–61% of the general population, suggesting a role of this disorder in increasing the risk of trauma exposure [34]. The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) reported a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD in 38.8% of individuals with bipolar I disorder [38,39]. Further studies showed that the prevalence of PTSD is increased in bipolar patients [35,40-45]. In previous studies, exploring Italian PTSD patients, a correlation was found between lifetime subthreshold manic-hypomanic and depressive symptoms and both the likelihood of suicidal ideations or attempts [46].

The aims of this study were to explore, in a sample of high school students survived from the L’Aquila earthquake 21 months earlier, the relationships between manic-hypomanic spectrum symptoms and post-traumatic spectrum symptoms and the gender differences in these relationships.

Methods

Study participants

The study sample included 512 high school seniors (280 males and 232 females) from L’Aquila (Italy). All subjects were living in the town of L’Aquila at the time the earthquake occurred; all of them were exposed to the April 6, 2009 earthquake. Assessments were performed 21 months after the exposure.

Out of the 10 high school students in L’Aquila, 3 were chosen with technical, scientific, and humanistic orientation programs, respectively. No a priori inclusion or exclusion criteria were used. These schools have students with wide and representative socioeconomic backgrounds. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of L’Aquila and the school council approved all recruitment and assessment procedures. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Eligible subjects provided written informed consent, after receiving a complete description of the study and having the opportunity to ask questions. Subjects were not paid for their participation in accordance with the Italian law for clinical studies.

Instruments and assessments

Assessment instruments included the Trauma and Loss Spectrum-Self Report (TALS-SR) [47,48] and the Mood Spectrum-Self Report (MOODS-SR) [49], lifetime versions. These instruments were developed by the authors who comprise the Italian–American team of researchers belonging to the so called Spectrum Project: an international collaboration research project between researchers of the Universities of Pisa (Italy), Pittsburgh (USA), Columbia (New York, USA), and California at San Diego (USA), established to develop and test assessment instruments for the assessment of the spectrum of clinical features associated with the current version of DSM psychiatric disorders. The spectrum model highlights the significance of isolated symptoms and subthreshold symptom clusters that accompany each disorder classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and may follow or be manifested in concurrence with the main disorder [50,51]. Originally developed in English, the interviews and self-reports were then translated into Italian, back translated, and then revised for inconsistencies between the two languages. Spectrum assessments for the major mental disorders have been developed [48,49,52-56]. In the present study, we used the final Italian version of the TALS-SR and MOODS-SR.

The TALS-SR is a questionnaire developed for assessing post-traumatic spectrum symptoms [48]. It includes 116 items exploring the lifetime experience of a range of loss and/or traumatic events and lifetime symptoms, behaviors, and personal characteristics that might represent manifestations and/or risk factors for the development of a stress response syndrome. The instrument is organized into nine domains including: loss events (I); grief reactions (II); potentially traumatic events (III); reactions to losses or upsetting events (IV); re-experiencing (V); avoidance and numbing (VI); maladaptive coping (VII); arousal (VIII); and personal characteristics/risk factors (IX). Domain VII, maladaptive coping, specifically investigates maladaptive coping and behaviors including no self-care, scarce adherence to ongoing medications, alcohol or drug abuse, risk-taking behaviors (dangerous driving, promiscuous sex, etc.), thoughts of death, and suicidal ideations and attempts. The responses to the items are coded in a dichotomous way (yes/no) and domain scores are obtained by counting the number of positive answers. In line with previous studies, symptom criteria were derived from the positive answers to the TALS-SR items corresponding to the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD [7,8,10].

The MOODS-SR consists of 161 items coded as present or absent for one or more periods of at least 3–5 days throughout the subject’s lifetime. The items are organized into manic and depressive components as well as into a section that assesses disturbances in rhythmicity and vegetative functions, yielding a total of seven domains. In fact, both the manic and the depressive components are subtyped into three domains exploring mood, energy, and cognition symptoms, respectively. The number of the mood-, energy-, and cognition-manic items endorsed by subjects makes up the manic component (62 items) while the sum of the mood-, energy-, and cognition-depressive items constitutes the depressive component (63 items). The rhythmicity and vegetative function domain (29 items) explores alterations in the circadian rhythms and vegetative functions, including changes in energy, physical well-being, mental and physical efficiency related to the weather and season, and changes in appetite, sleep, and sexual activities.

Statistical analyses

Mann–Whitney test was computed in order to compare MOODS-SR and TALS-SR domain scores as they are not normally distributed.

Multiple linear regression models were utilized to study the relationships between MOODS-SR depressive and manic-hypomanic components and TALS-SR maladaptive symptoms.

Scattergrams, univariate linear regressions, and coefficients of determination were utilized to evaluate the specific relationship between the MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and the TALS-SR maladaptive coping domain in PTSD by gender and non-PTSD by gender subgroups. Further, t-tests were computed to compare the slopes of the regression lines.

Eight point biserial correlation coefficients were computed to study the strength of association between MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and each TALS-SR maladaptive coping domain item in PTSD by gender subgroups.

Finally, χ2 tests were computed in order to compare the rates of endorsement of the TALS-SR maladaptive coping items between the two genders.

Results

Full data were available for 475 young adults (94.2% of the overall sample, mean age 17.67 ± 0.78), 203 women and 272 men. Among the 475 young adults enrolled, 169 (35.6%) subjects presented a diagnosis of PTSD according to DSM-5 [13], with significantly higher rates in females than in males (n =104; 51.2% vs n =65; 23.9%, respectively, p < .001).

All MOODS-SR and TALS-SR domain scores were significantly higher in survivors with DSM-5 PTSD with respect to those without (p < .001). Among survivors with DSM-5 PTSD, females reported significantly higher scores in MOOD-SR mood-depressive (p = .045) and rhythmicity and vegetative function (p = .027) domains and in TALS-SR loss events (p = .004), reactions to losses or upsetting events (p = .001), re-experiencing (p = .002), and arousal (p < .001) domains with respect to males. Conversely, the males showed significantly higher scores than females in the TALS-SR maladaptive coping domain only (p = .012) (Table 1).

Table 1.

MOODS-SR and TALS-SR domain scores in 475 L’Aquila survivors with DSM-5 PTSD: gender differences

| Total | Males | Females | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | ||

| MOODS-SR | ||||

| Mood-depressive | 11.36 ± 5.13 | 10.25 ± 5.43 | 12.06 ± 4.82 | .045 |

| Mood-manic | 12.73 ± 4.96 | 13.22 ± 5.62 | 12.43 ± 4.49 | .558 |

| Energy-depressive | 3.93 ± 2.20 | 3.55 ± 2.26 | 4.17 ± 2.14 | .090 |

| Energy-manic | 5.40 ± 2.58 | 5.11 ± 2.80 | 5.59 ± 2.42 | .320 |

| Cognition-depressive | 10.02 ± 5.48 | 9.72 ± 6.29 | 10.20 ± 4.93 | .434 |

| Cognition-manic | 7.20 ± 4.59 | 7.78 ± 5.40 | 6.84 ± 3.99 | .414 |

| Rhythmicity | 12.02 ± 5.42 | 10.71 ± 6.27 | 12.85 ± 4.66 | .027 |

| Total depressive | 25.31 ± 11.10 | 23.52 ± 11.61 | 26.43 ± 10.67 | .059 |

| Total manic | 25.34 ± 9.96 | 26.11 ± 11.20 | 24.85 ± 9.13 | .643 |

| TALS-SR | ||||

| Loss events | 4.33 ± 1.72 | 3.85 ± 1.72 | 4.63 ± 1.67 | .004 |

| Grief reactions | 12.66 ± 5.37 | 11.92 ± 5.50 | 13.12 ± 5.27 | .166 |

| Potential traumatic events | 4.73 ± 2.54 | 4.80 ± 2.88 | 4.68 ± 2.31 | .923 |

| Reactions to losses | 10.14 ± 3.03 | 9.12 ± 2.86 | 10.78 ± 2.96 | .001 |

| Re-experiencing | 5.08 ± 1.71 | 4.59 ± 1.78 | 5.41 ± 1.59 | .002 |

| Avoidance and numbing | 5.88 ± 1.69 | 5.64 ± 1.71 | 6.03 ± 1.67 | .096 |

| Maladaptive coping | 1.52 ± 1.47 | 1.85 ± 1.49 | 1.32 ± 1.42 | .012 |

| Arousal | 3.34 ± 1.20 | 2.75 ± 1.22 | 3.71 ± 1.03 | <.001 |

Eight multiple linear regression models were applied to the PTSD subgroup to explore the possible relationship between the MOODS-SR depressive and manic-hypomanic components (assumed as predictors) and each of the eight TALS-SR domains (assumed as dependent variables). A significant positive association emerged between the MOODS-SR depressive component and each one of the TALS-SR domains; conversely the MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component had a significant positive association with TALS-SR potentially traumatic events [b =0.06, (SE =0.01), p < .001] and maladaptive coping [b =0.02, (SE =0.01), p = .031] domains only.

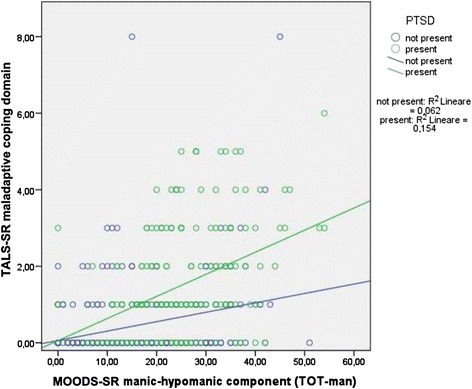

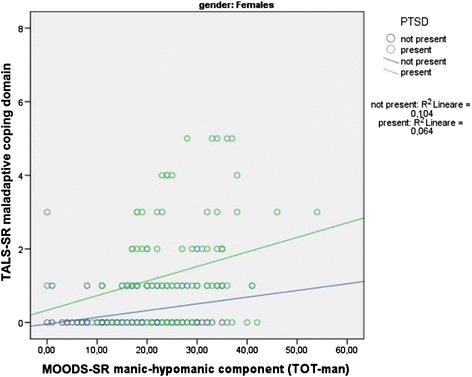

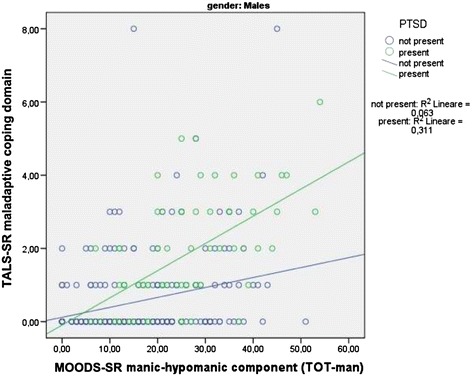

Two t-tests applied to the regression line slopes comparing survivors with PTSD with respect to those without, for what concern the association between the MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and the TALS-SR domains, showed a significantly stronger association with the maladaptive coping domain only [b =0.06 (SE =0.01) vs b =0.03 (SE =0.01), t =2.95, p < .010] (see scattergram in Figure 1) that was confirmed among males [b =0.07 (SE =0.01) vs b =0.03 (SE =0.01); t =2.99; p < .010] but not females [b =0.04 (SE =0.01) vs b =0.02 (SE =0.01); t =1.39; p = n.s.] (see scattergrams in Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Relationships between MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and TALS-SR maladaptive coping domain in subjects with and without DSM-5 PTSD.

Figure 2.

Relationships between MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and TALS-SR maladaptive coping domain among females with and without DSM-5 PTSD.

Figure 3.

Relationships between MOOD-SR manic-hypomanic component and TALS-SR maladaptive coping domain among males with and without PTSD.

Computation of the point biserial correlation coefficients showed a significant “moderate” relationship between the MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and the TALS-SR maladaptive domain items N =97 (“Stop taking care of yourself, for example not getting enough rest or not eating right?”), N =98 (“Stop taking prescribed medications or fail to follow up with medical recommendations…?”), and N =100 (“Engage in risk-taking behaviors…?”) among survivors with PTSD.

Further, PTSD males showed a significant “moderate” correlation on TALS-SR items N =97 (“Stop taking care of yourself, for example not getting enough rest or not eating right?”), N =100 (“Engage in risk-taking behaviors…?”), and N =103 (“Intentionally scratch, cut, burn, or hurt yourself…?”) and also a significant “good” correlation on N =98 (“Stop taking prescribed medications or fail to follow up with medical recommendations…?”). Conversely, PTSD females showed a significant “good” correlation on item N =100 only (“Engage in risk-taking behaviors…?”).

A significantly higher correlation coefficient emerged in PTSD males than females for item N =98 only (“Stop taking prescribed medications or fail to follow up with medical recommendations…?”) (r = .410 vs r = .098, z =2.09, p = .040) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Point biserial correlation coefficients: association of TALS-SR maladaptive coping domain items and MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component in the total sample of DSM-5 PTSD survivors and divided by gender

| TALS-SR maladaptive items | PTSD total ( r ) | PTSD males ( r ) | PTSD females ( r ) | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97 | …Stop taking care of yourself, for example not getting enough rest or not eating right? | .218* | .365* | .133 | 1.54 | .12 |

| 98 | …Stop taking prescribed medications or fail to follow up with medical recommendations, such as appointments, diagnostic test or a diet? | .256* | .410* | .098 | 2.09 | .04 |

| 99 | … Use alcohol or drugs or over-the-counter medications to calm yourself or to relieve emotional or physical pain? | .194* | .209 | .172 | 0.24 | .81 |

| 100 | …Engage in risk-taking behaviors, such as driving fast, promiscuous sex, hanging out in dangerous neighborhoods? | .387* | .354* | .428* | −0.54 | .59 |

| 101 | …Wish you hadn’t survived? | .015 | .061 | −.031 | 0.57 | .57 |

| 102 | …Think about ending your life? | .188* | .192 | .173 | 0.12 | .90 |

| 103 | …Intentionally scratch, cut, burn, or hurt yourself? | .148 | .281* | −.004 | 1.81 | .07 |

| 104 | …Attempt suicide? | .102 | .101 | .091 | 0.06 | .95 |

*p < .05.

The rates of endorsement of each TALS-SR maladaptive items in males and females with PTSD are reported in Table 3. Male survivors showed a significantly higher endorsement of TALS-SR maladaptive item 100 (“Engage in risk-taking behaviors…?”) than females.

Table 3.

Gender differences in the TALS-SR maladaptive coping items endorsement among DSM-5 PTSD survivors

| TALS-SR maladaptive items | Total PTSD | PTSD males | PTSD females | χ 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97 | …Stop taking care of yourself, for example not getting enough rest or not eating right? | 78(46.2%) | 24(36.9%) | 54(51.9%) | 3.043 | .081 |

| 98 | …Stop taking prescribed medications or fail to follow up with medical recommendations, such as appointments, diagnostic test or a diet? | 25(14.8%) | 13(20.0%) | 12(11.5%) | 1.650 | .199 |

| 99 | … Use alcohol or drugs or over-the-counter medications to calm yourself or to relieve emotional or physical pain? | 47(27.8%) | 22(33.8%) | 25(24.0%) | 1.459 | .227 |

| 100 | …Engage in risk-taking behaviors, such as driving fast, promiscuous sex, hanging out in dangerous neighborhoods? | 38(22.5%) | 25(38.5%) | 13(12.5%) | 14.015 | <.001 |

| 101 | …Wish you hadn’t survived? | 29(17.2%) | 13(20.0%) | 16(15.4%) | 0.319 | .572 |

| 102 | …Think about ending your life? | 16(9.5%) | 9(13.8%) | 7(6.7%) | 1.606 | .205 |

| 103 | …Intentionally scratch, cut, burn, or hurt yourself? | 16(9.5%) | 9(13.8%) | 7(6.7%) | 1.606 | .205 |

| 104 | …Attempt suicide? | 8(4.7%) | 5(7.7%) | 3(2.9%) | 1.123 | .289 |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore gender differences in DSM-5 new maladaptive symptoms in a sample of earthquake survivors with PTSD diagnosed in accordance to DSM-5 criteria, besides their correlations and those of post-traumatic spectrum symptoms with lifetime mood spectrum symptoms.

Our results show significantly higher rates of endorsement in both the MOODS-SR manic and depressive domains in survivors with DSM-5 PTSD with respect to those without. Further, significant gender differences emerged among survivors with DSM-5 PTSD, both in the MOODS-SR depressive and rhythmicity and vegetative function components and in the TALS-SR loss events, reaction to losses, and re-experiencing and arousal domains. In all these cases, women reported significantly higher scores than men. Conversely, significantly higher rates emerged in men with respect to women for what concern the TALS-SR maladaptive domain only. These data are in line with previous literature highlighting gender differences in PTSD symptomatology diagnosed in accordance to DSM-IV-TR criteria with women usually reporting higher post-traumatic stress symptoms and men showing significantly higher rates of self-destructive or maladaptive behaviors [8,26,27,29-32,57].

Exploring the correlations between the MOODS-SR and the TALS-SR, a significant correlation emerged between the MOODS-SR depressive component and all TALS-SR domains among survivors with PTSD. Among the same subjects, a statistically significant correlation emerged between the MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and the TALS-SR potentially traumatic events and maladaptive coping domains only. These data corroborate previous research highlighting a correlation between bipolar disorder comorbidity and an increased risk for potentially traumatic exposure [34-36]. Otto et al. (2004), in fact, reported a 16% prevalence of PTSD in a sample of 1,214 patients with BD [35]. Among the risk factors for PTSD, bipolar subjects showed also the presence of greater trauma exposure. More recently, Pollack et al. (2006) studied 137 ongoing participants in the naturalistic, longitudinal study Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), who were indirectly exposed to September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks [36]. The authors reported in this sample a 20% PTSD prevalence rate. A new onset of PTSD was significantly associated with the presence of a hypomanic, manic, or mixed mood state at the time of trauma and mania/hypomania remained a significant predictor of PTSD in response to the September 11 attacks after controlling for peri-traumatic exposure and distress variables. Previous data on BD in PTSD highlighted not only high rates of such comorbidity but potential deleterious effects of trauma and PTSD on the course and outcome of BD and, conversely, of BD on the course and outcome of PTSD [39,58,59], recommending the need for further research. Our data corroborate these findings suggesting also a correlation between even subthreshold manic symptoms and an increased risk for maladaptive behaviors in PTSD.

The new symptom (E2) included in the DSM-5 PTSD criterion E (marked alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event), exploring reckless, maladaptive behaviors, addresses the important post-traumatic symptoms often seen in adolescents [29-32,60-63]. Friedman et al. (2011) suggested how the new DSM-5 criterion E encompasses more than the hyper-arousal addressed in previous DSM-IV-TR criterion D, better characterizing alterations in arousal and reactivity that are associated with the traumatic event [60]. Such a reframing of this symptom cluster enables us to include behavioral, as well as emotional indicators of such post-traumatic alterations. Our data are in line with the growing evidence that PTSD is associated with reckless and self-destructive behavior, particularly among young men. Israeli male adolescents, exposed to recurrent terrorism, exhibited marked increases in risk-taking behavior [15]. Reckless driving was observed among both adult individuals and adolescents with PTSD [26,64-67]. Risky sexual behaviors, sometimes associated with HIV risk was reported among college women, female prisoners, and adult male survivors of childhood sexual abuse [65,68]. Reckless behavior appears to be associated with PTSD to such an extent that it has been added to the diagnostic cluster assessing alterations in arousal and reactivity. It is of interest that our data seem to suggest a relationship between these symptoms and a bipolar diathesis particularly among young men with PTSD that should need further attention. Exploring the gender differences in the endorsement of the TALS-SR maladaptive domain items among survivors with PTSD, our results showed a statistically significant gender difference for what concern the item 100 only (“Engage in risk-taking behaviors…?”), with males reporting the highest rates. Looking at the point biserial correlation coefficients exploring the relationships between the MOODS-SR manic-hypomanic component and the TALS-SR maladaptive domain items, stronger correlations were confirmed in males. Our results seem to confirm the gender relevance outlined in the introduction section of DSM-5. The new manual points out the possible influence of gender not only on the overall risk for the development of a mental disorder, as shown by prevalence and incidence rates, but also on the likelihood of particular symptoms and consequently on the need of service provision.

Interpretation of our results should keep in mind some important limitations of the study. First, the most important is the use of self-report instruments that may be considered less accurate. Nevertheless, the use of TALS-SR allowed us to accurately compare the possible DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 criteria reported by the earthquake survivors. Second, as already mentioned in a previous study [10], is the lack of information on the presence of Axis I psychiatric comorbidities and the lack of assessment on the functional impairment. Third is the homogeneity of the study sample that included non-clinical high school students. Fourth, the MOODS-SR lifetime version did not permit to establish if the manic-hypomanic component was present before the onset of PTSD or emerged after it, so that no direction of causality could be determined. Further studies in larger samples of earthquake-exposed subjects are thus needed in order to confirm our results, particularly for what concern the gender differences.

Conclusion

Despite the abovementioned limitations, this study offers an important glimpse at the empirical performance of the DSM-5 PTSD criteria, suggesting the need for further studies in epidemiological samples to evaluate the change in prevalence rates of PTSD that may result by adopting the new DSM-5 criteria.

Abbreviations

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

- BD

Bipolar disorder

- TALS-SR

Trauma and Loss Spectrum-Self Report

- MOODS-SR

Mood Spectrum-Self Report

- STEP-BD

Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder

- NCS

National Comorbidity Survey

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CCar and LDO participated to the conception and design of the study, the interpretation of data, the draft and critical revision of this article. PS and AR participated to the conception and design of the study and critical revision of this article. GM performed the statistical analyses. CCon and CAB participated to the critical revision of the article. All authors agreed to be cited as co-authors, accepting the order of authorship, and approved the final version of manuscript and the manuscript submission to Annals of General Psychiatry.

Contributor Information

Claudia Carmassi, Email: ccarmassi@gmail.com.

Paolo Stratta, Email: psystr@tin.it.

Gabriele Massimetti, Email: gabriele.massimetti@med.unipi.it.

Carlo Antonio Bertelloni, Email: carlo.ab@hotmail.it.

Ciro Conversano, Email: psicologiaapplicata@gmail.com.

Ivan Mirko Cremone, Email: ivan.cremone@gmail.com.

Mario Miccoli, Email: mario.miccoli@med.unipi.it.

Angelo Baggiani, Email: angelo.baggiani@med.unipi.it.

Alessandro Rossi, Email: alessandro.rossi@cc.univaq.it.

Liliana Dell’Osso, Email: liliana.dellosso@med.unipi.it.

References

- 1.Maj M, Starace F, Crepet P, Lobrace S, Veltro F, De Marco F, Kemali D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among subjects exposed to a natural disaster. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79:544–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armenian HK, Morikawa M, Melkonian AK, Hovanesian A, Akiskal K, Akiskal HS. Risk factors for depression in the survivors of the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. J Urban Health. 2002;79:373–382. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.3.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai TJ, Chang CM, Connor KM, Lee LC, Davidson JR. Full and partial PTSD among earthquake survivors in rural Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hussain A, Weisaeth L, Heir T. Psychiatric disorders and functional impairment among disaster victims after exposure to a natural disaster: a population based study. J Affect Disord. 2011;128:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ditlevsen DN, Elklit A. Gender, trauma type, and PTSD prevalence: a re-analysis of 18 nordic convenience samples. Annals General Psychiatry. 2012;11(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Massimetti G, Conversano C, Daneluzzo E, Riccardi I, Stratta P, Rossi A. Impact of traumatic loss on post-traumatic spectrum symptoms in high school students after the L’Aquila 2009 earthquake in Italy. J Affect Disord. 2011;134:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Massimetti G, Daneluzzo E, Di Tommaso S, Rossi A. Full and partial PTSD among young adult survivors 10 months after the L’Aquila 2009 earthquake: gender differences. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Massimetti G, Stratta P, Riccardi I, Capanna C, Akiskal KK, Akiskal KS, Rossi A. Age, gender and epicenter proximity effects on post-traumatic stress symptoms in L’Aquila 2009 earthquake survivors. J Affect Disord. 2013;2:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmassi C, Akiskal HS, Bessonov D, Massimetti G, Calderani E, Stratta P, Rossi A, Dell’Osso L. Gender differences in DSM-5 versus DSM-IV-TR PTSD prevalence and criteria comparison among 512 survivors to the L’Aquila earthquake. J Affect Disord. 2014;160:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmassi C, Akiskal HS, Yong SS, Stratta P, Calderani E, Massimetti E, Akiskal KK, Rossi A, Dell’Osso L. Post-traumatic stress disorder in DSM-5: estimates of prevalence and criteria comparison versus DSM-IV-TR in a non-clinical sample of earthquake survivors. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual: Mental Disorders, DSM-III. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing Incorporated; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-IV-TR. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irwin CE., Jr The theoretical concept of at-risk adolescents. Adolesc Med. 1990;1:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pat-Horenczyk R, Peled O, Miron T, Brom D, Villa Y, Chemtob CM. Risk-taking behaviors among Israeli adolescents exposed to recurrent terrorism: provoking danger under continuous threat? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:66–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartley SL, Sikora DM, McCoy R. Prevalence and risk factors of maladaptive behaviour in young children with Autistic Disorder. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2008;52:819–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Stratta P, Rossi A. Maladaptive behaviours after catastrophic events: the contribute of a “spectrum” approach to post traumatic stress disorders. Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems. 2012;14:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Stratta P, Massimetti G, Akiskal KK, Akiskal HS, Maremmani I, Rossi A. Gender differences in the relationship between maladaptive behaviors and post-traumatic stress disorder. a study on 900 L’ Aquila 2009 earthquake survivors. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:111. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMillen JC, North CS, Smith EM. What parts of PTSD are normal: intrusion, avoidance, or arousal? Data from the Northridge, California, earthquake. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:57–75. doi: 10.1023/A:1007768830246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bal A, Jensen B. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptom clusters in Turkish child and adolescent trauma survivors. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16:449–457. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goenjian AK, Walling D, Steinberg AM, Roussos A, Goenjian HA, Pynoos RS. Depression and PTSD symptoms among bereaved adolescents 6(1/2) years after the 1988 Spitak earthquake. J Affect Disord. 2009;112:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cairo JB, Dutta S, Nawaz H, Hashmi S, Kasl S, Bellido E. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among adult earthquake survivors in Peru. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2010;4:39–46. doi: 10.1017/S1935789300002408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Conversano C, Massimetti G, Corsi M, Stratta P, Akiskal KK, Rossi A, Akiskal HS. Post-traumatic stress spectrum and maladaptive behaviours (drug abuse included) after catastrophic events: L’Aquila 2009 earthquake as case study. Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems. 2012;14:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakupcak M, Conybeare D, Phelps L, Hunt S, Holmes HA, Felker B, Klevens M, McFall ME. Anger, hostility, and aggression among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans reporting PTSD and subthreshold PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:945–954. doi: 10.1002/jts.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Fuller SR, Calhoun PS, Kinneer PM, Beckham JC. Correlates of anger and hostility in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1051–1058. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fear NT, Iversen AC, Chatterjee A, Jones M, Greenberg N, Hull L, Rona RJ, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Risky driving among regular armed forces personnel from the United Kingdom. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuhn E, Drescher K, Ruzek J, Rosen C. Aggressive and unsafe driving in male veterans receiving residential treatment for PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:399–402. doi: 10.1002/jts.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kronish IM, Edmondson D, Li Y, Cohen BE. Post-traumatic stress disorder and medication adherence: results from the Mind Your Heart study. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:1595–1599. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glodich A, Allen J. Adolescents exposed to violence and abuse: a review of the group therapy literature with an emphasis on preventing trauma reenactment. J Child Adolesc Group Ther. 1998;8:135–154. doi: 10.1023/A:1022988218910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugar M: Severe physical trauma in adolescence. In Trauma and adolescence. Edited by Madison SM. International Universities Press; 1999:183–201.

- 31.Gore-Felton C, Koopman C. Traumatic experiences: harbinger of risk behavior among HIV-positive adults. J Trauma Dissociation. 2002;3:121–135. doi: 10.1300/J229v03n04_07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens SJ, Murphy BS, McKnight K. Traumatic stress and gender differences in relationship to substance abuse, mental health, physical health, and HIV risk behavior in a sample of adolescents enrolled in drug treatment. Child Maltreat. 2003;8:46–57. doi: 10.1177/1077559502239611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Rosenberg SD. Premilitary MMPI scores as predictors of combat-related PTSD symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:479–483. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otto MW, Perlman CA, Wernicke R, Reese HE, Bauer MS, Pollack MH. Posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with bipolar disorder: a review of prevalence, correlates, and treatment strategies. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:470–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollack MH, Simon NM, Fagiolini A, Pitman R, McNally RJ, Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Sachs GS, Perlman C, Ghaemi SN, Thase ME, Otto MW. Persistent posttraumatic stress disorder following September 11 in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:394–399. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strawn JR, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Hanseman D, Maue DK, Bitter S, Kraft EM, Geracioti TD, Strakowski SM, DelBello MP. Post-traumatic stress symptoms and trauma exposure in youth with first episode bipolar disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4:169–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1079–1089. doi: 10.1017/S0033291797005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mueser KT, Goodman LB, Trumbetta SL, Rosenberg SD, Osher FC, Vidaver R, Auciello P, Foy DW. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:493–499. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assion HJ, Brune N, Schmidt N, Aubel T, Edel MA, Basilowski M, Juckel G, Frommberger U. Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder in bipolar disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:1041–1049. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvarez MJ, Roura P, Foguet Q, Oses A, Sola J, Arrufat FX. Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity and clinical implications in patients with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200:549–552. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318257cdf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Musetti L, Socci C, Shear MK, Conversano C, Maremmani I, Perugi G. Lifetime mood symptoms and adult separation anxiety in patients with complicated grief and/or post-traumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernandez JM, Cordova MJ, Ruzek J, Reiser R, Gwizdowski IS, Suppes T, Ostacher MJ. Presentation and prevalence of PTSD in a bipolar disorder population: a STEP-BD examination. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Hare T, Sherrer M. Lifetime trauma, subjective distress, substance use, and PTSD symptoms in people with severe mental illness: comparisons among four diagnostic groups. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49:728–732. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Rucci P, Ciapparelli A, Paggini R, Ramacciotti CE, Conversano C, Balestrieri M, Marazziti D. Lifetime subthreshold mania is related to suicidality in posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectrums. 2009;14:262–266. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900025426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dell’Osso L, Shear MK, Carmassi C, Rucci P, Maser JD, Frank E, Endicott J, Lorettu L, Altamura CA, Carpiniello B, Perris F, Conversano C, Ciapparelli A, Carlini M, Sarno N, Cassano GB. Validity and reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for the Trauma and Loss Spectrum (SCI-TALS) Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Rucci P, Conversano C, Shear MK, Calugi S, Maser JD, Endicott J, Fagiolini A, Cassano GB. A multidimensional spectrum approach to post-traumatic stress disorder: comparison between the Structured Clinical Interview for Trauma and Loss Spectrum (SCI-TALS) and the Self-Report instrument (TALS-SR) Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dell’Osso L, Armani A, Rucci P, Frank E, Fagiolini A, Corretti G, Shear MK, Grochocinski VJ, Maser JD, Endicott J, Cassano GB. Measuring mood spectrum: comparison of interview (SCI-MOODS) and self-report (MOODS-SR) instruments. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43:69–73. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.29852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frank E, Cassano GB, Shear MK, Rotondo A, Dell’Osso L, Mauri M, Maser J, Grochocinski V. The spectrum model: a more coherent approach to the complexity of psychiatric symptomatology. CNS Spectrums. 1998;3:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cassano GB, Dell’Osso L, Frank E, Miniati M, Fagiolini A, Shear K, Pini S, Maser J. The bipolar spectrum: a clinical reality in search of diagnostic criteria and an assessment methodology. J Affect Disord. 1999;54:319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00158-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shear MK, Frank E, Rucci P, Fagiolini DA, Grochocinski VJ, Houck P, Cassano GB, Kupfer DJ, Endicott J, Maser JD, Mauri M, Banti S. Panic-agoraphobic spectrum: reliability and validity of assessment instruments. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(01)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dell’Osso L, Rucci P, Cassano GB, Maser JD, Endicott J, Shear MK, Sarno N, Saettoni M, Grochocinski VJ, Frank E. Measuring social anxiety and obsessive-compulsive spectra: comparison of interviews and self-report instruments. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43:81–87. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.30795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sbrana A, Dell’Osso L, Gonnelli C, Impagnatiello P, Doria MR, Spagnolli S, Ravani L, Cassano GB, Frank E, Shear MK, Grochocinski VJ, Rucci P, Maser JD, Endicott J. Acceptability, validity and reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for the Spectrum of Substance Use (SCI-SUBS): a pilot study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12:105–115. doi: 10.1002/mpr.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sbrana A, Bizzarri JV, Rucci P, Gonnelli C, Doria MR, Spagnolli S, Ravani L, Raimondi F, Dell’Osso L, Cassano GB. The spectrum of substance use in mood and anxiety disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sbrana A, Dell’Osso L, Benvenuti A, Rucci P, Cassano P, Banti S, Gonnelli C, Doria MR, Ravani L, Spagnolli S, Rossi L, Raimondi F, Catena M, Endicott J, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Cassano GB. The psychotic spectrum: validity and reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for the Psychotic Spectrum. Schizophr Res. 2005;75:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carmassi C, Dell’Osso L, Manni C, Candini V, Dagani J, Iozzino L, Koenen KC, de Girolamo G: Frequency of trauma exposure and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Italy: analysis from the World Mental Health Survey Initiative.J Psychiatr Res 2014, doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Thatcher JW, Marchand WR, Thatcher GW, Jacobs C, Jensen C. Clinical characteristics and health service use of veterans with comorbid bipolar disorder and PTSD. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:703–707. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dell’Osso L, Stratta P, Conversano C, Massimetti E, Akiskal KK, Akiskal HS, Rossi A, Carmassi C. Lifetime mania is related to post-traumatic stress symptoms in high school students exposed to the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(2):357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friedman MJ, Resick PA, Bryant RA, Brewin CR. Considering PTSD for DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:750–769. doi: 10.1002/da.20767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stratta P, Capanna C, Riccardi I, Carmassi C, Piccinni A, Dell’Osso L, Rossi A. Suicidal intention and negative spiritual coping one year after the earthquake of L’Aquila (Italy) J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):1227–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C. PTSD 30 years after DSM-III: Current controversies and future challenges. Ital J Psychopathol. 2011;17(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hardoy MC, Carta MG, Marci AR, Carbone F, Cadeddu M, Kovess V, Dell’Osso L, Carpiniello B. Exposure to aircraft noise and risk of psychiatric disorders: the Elmas survey–aircraft noise and psychiatric disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(1):24–26. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0837-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lowinger T, Solomon Z. PTSD, guilt, and shame among reckless drivers. J Loss and Trauma. 2004;9:327–344. doi: 10.1080/15325020490477704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Green BL, Krupnick JL, Stockton P, Goodman L, Corcoran CB, Petty R. Effects of adolescent trauma exposure on risky behavior in college women. Psychiatry. 2005;68:363–378. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2005.68.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lapham SC, C’de Baca J, McMillan GP, Lapidus J. Psychiatric disorders in a sample of repeat impaired-driving offenders. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:707–713. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Gemignani S, Bertelloni CA, Stratta P, Rossi A. Post-traumatic stress spectrum in the DSM-5 era: what we learned from the L’Aquila experience. Journal of Psychopathology. 2014;20(2):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hutton HE, Treisman GJ, Hunt WR, Fishman M, Kendig N, Swetz A, Lyketsos CG. HIV risk behaviors and their relationship to posttraumatic stress disorder among women prisoners. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;54:508–513. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]