Abstract

Purpose of review

High levels of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) cause rare disorders of hypophosphatemic rickets and are a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Despite major advances in understanding FGF23 biology, fundamental aspects of FGF23 regulation in health and in CKD remain mostly unknown.

Recent findings

Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) is caused by gain-of-function mutations in FGF23 that prevent its proteolytic cleavage, but affected individuals experience a waxing and waning course of phosphate wasting. This led to the discovery that iron deficiency is an environmental trigger that stimulates FGF23 expression and hypophosphatemia in ADHR. Unlike osteocytes in ADHR, normal osteocytes couple increased FGF23 production with commensurately increased FGF23 cleavage to ensure that normal phosphate homeostasis is maintained in the event of iron deficiency. Simultaneous measurement of FGF23 by intact and C-terminal assays supported these breakthroughs by providing minimally invasive insight into FGF23 production and cleavage in bone. These findings also suggest a novel mechanism of FGF23 elevation in patients with CKD, who are often iron deficient and demonstrate increased FGF23 production and decreased FGF23 cleavage, consistent with an acquired state that mimics the molecular pathophysiology of ADHR.

Summary

Iron deficiency stimulates FGF23 production, but normal osteocytes couple increased FGF23 production with increased cleavage to maintain normal circulating levels of biologically active hormone. These findings uncover a second level of FGF23 regulation within osteocytes, failure of which culminates in elevated levels of biologically active FGF23 in ADHR and perhaps CKD.

Keywords: FGF23, iron, iron deficiency, phosphate, osteocyte, rickets, ADHR, CKD

Introduction

Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) is a hormone produced in osteocytes that controls phosphate and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D homeostasis [1]. Activation of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)/α-Klotho co-receptor complexes by FGF23 reduces renal phosphate reabsorption by down regulating the sodium phosphate co-transporters NPT2a and NPT2c [2, 3]. FGF23 also suppresses circulating levels of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D by inhibiting vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase (Cyp27b1) and stimulating 24-hydroxylase expression (Cyp24a1) in the kidney, which produces and degrades 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D, respectively [2]. In normal mice and healthy humans, circulating FGF23 levels rise and fall in parallel to dietary phosphate intake, ensuring that serum phosphate remains within the normal range regardless of intake [4–6].

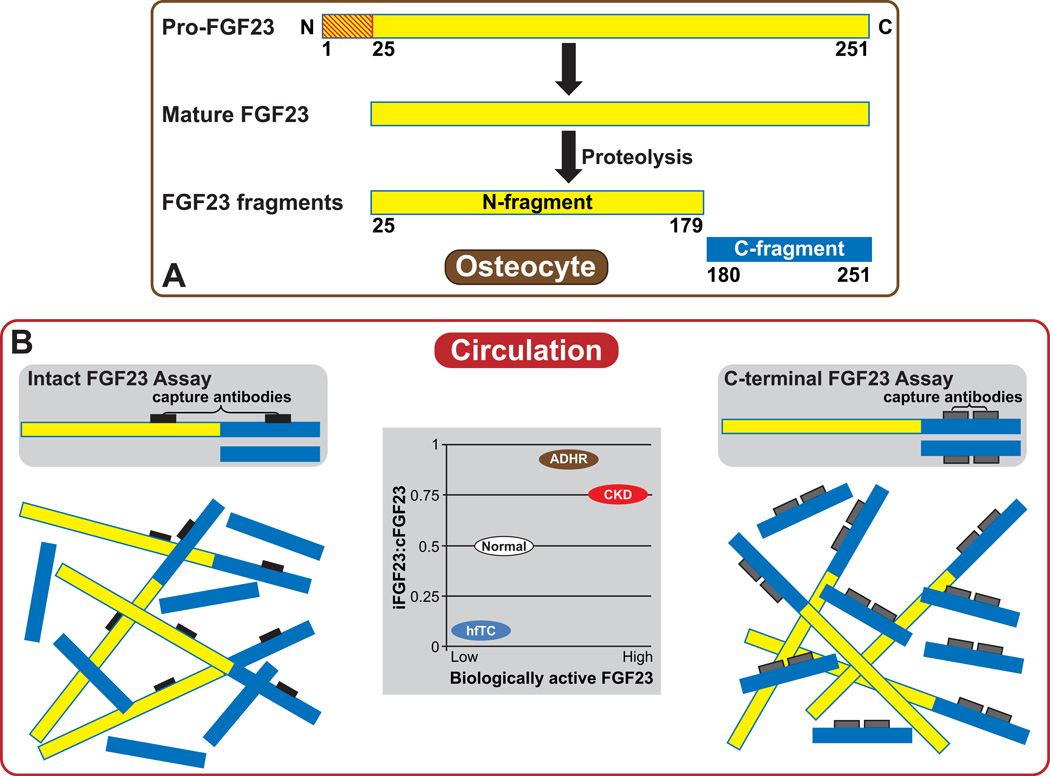

Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) is the prototype disorder of primary FGF23 excess [1]. Gain-of-function mutations in FGF23 (R176Q/W and R179Q/W) replace R176 or R179 in the R176HTR179/S180 subtilisin-like proprotein convertase (SPC) cleavage motif that separates the conserved N-terminal region of FGF23 from its variable C-terminal tail [1, 7]. When wild-type Fgf23 is expressed in mammalian cells, full length FGF23 (32 kD) and cleaved N- and C-terminal peptide fragments (20 and 12 kD) are secreted (Figure 1A). In contrast, when ADHR-mutant Fgf23 is expressed, inability to recognize the mutated cleavage motif results in secretion of primarily full-length FGF23 [8, 9]. A dynamic system involving intracellular proteolysis likely inactivates FGF23 (by an unknown mechanism), as only full-length FGF23 but not its N-terminal (residues 25–179) or C-terminal (residues 180–251) fragments is capable of lowering serum phosphate concentrations when injected into mice [9]. As a result of elevated FGF23 levels, ADHR is characterized by hypophosphatemia, renal phosphate wasting, inappropriately low levels of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D for the degree of hypophosphatemia, and vitamin D-resistant rickets [10, 11].

Figure 1. Schematic of FGF23 processing and strategies to quantify circulating FGF23 levels.

(A) FGF23 is expressed in osteocytes as a 251-amino acid protein. A 24-amino acid N-terminal signaling peptide (red striped) is cleaved to form the mature molecule, which can then be secreted intact or cleaved within osteocytes between amino acids 179 and 180 to form inactive N-terminal and C-terminal fragments.

(B) Two types of commercially available ELISAs detect FGF23 using different molecular strategies. Intact assays use capture antibodies (black) that bind two epitopes that flank the proteolytic cleavage of FGF23 site so that only biologically active, intact FGF23 (amino acids 25–251) is detected. C-terminal assays use capture antibodies (gray) that bind two epitopes in the C-terminus of FGF23 so that both biologically active, intact FGF23 and its inactive C-terminal fragments (amino acids 180–251) are detected. Inset schematic: The ratio of circulating iFGF23:cFGF23 (y-axis) can provide minimally invasive insight into FGF23 production and cleavage in bone across different clinical settings characterized by a spectrum of biologically active FGF23 levels, for example, hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis (hfTC), autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR), and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is the prototype disorder of secondary FGF23 excess [12]. As kidney function progressively declines, circulating FGF23 levels and urinary fractional excretion of phosphate increase, while 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D levels decrease leading to secondary hyperparathyroidism [13, 14]. Normal to high serum phosphate differentiates secondary FGF23 excess due to CKD from ADHR and other hypophosphatemic forms of primary FGF23 excess. Despite rapid advances in FGF23 research in CKD, mechanisms of elevated levels remain poorly understood. Given recent data linking elevated FGF23 levels to higher risks of cardiovascular disease and death [15–25], more thorough understanding of FGF23 regulation is needed to guide novel therapeutic approaches to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Measuring circulating FGF23 levels

Commercially available enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) quantify circulating FGF23 concentrations using two strategies that differ based on the position of the epitopes on FGF23 that their capture antibodies recognize (Figure 1B). Intact FGF23 assays (iFGF23) measure biologically active FGF23 exclusively because the capture antibodies recognize two epitopes that flank the proteolytic cleavage site that lays between amino acids 179 and 180 [26]. C-terminal assays (cFGF23) detect both intact FGF23 and its C-terminal fragments because the capture antibodies recognize two epitopes in the C-terminus, distal to the proteolytic cleavage site [27].

The ratio of iFGF23:cFGF23 may serve as a useful surrogate measure to compare the fraction of total circulating FGF23 species that represent intact, biologically active hormone across different clinical settings (Figure 1B). In active ADHR, iFGF23 and cFGF23 assays yield similarly elevated results and the iFGF23:cFGF23 ratio approaches one because virtually all circulating FGF23 is intact [28]. At the other end of the clinical spectrum, hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis (hfTC) is a syndrome of primary FGF23 deficiency caused by loss-of-function mutations in Fgf23 or Galnt3 that fail to protect FGF23 from rapid degradation [29–34]. As a result of excessive degradation, levels of iFGF23 are often undetectable but cFGF23 levels are highly elevated, resulting in an iFGF23:cFGF23 ratio that approaches zero [32, 34, 35]. Healthy individuals lie in between these extremes with normal levels of biologically active FGF23, variable levels of FGF23 fragments, and an intermediate iFGF23:cFGF23 ratio [4, 36, 37]. Thus, simultaneously measuring iFGF23 and cFGF23 in peripheral blood samples could yield important, minimally invasive insight into FGF23 transcription and cleavage in bone.

It is important to emphasize, however, that operationalizing measurements of iFGF23:cFGF23 ratios for clinical diagnosis or for research is currently limited by the different units each assay reports, pg/ml for iFGF23 and RU/ml for cFGF23. A single assay platform capable of simultaneously measuring iFGF23 and cFGF23 in blood specimens and reporting each in pg/ml would represent an important technical advance for the field.

Clinical observations in ADHR suggest a link between iron and FGF23

ADHR is characterized by incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity with onset at birth or later ages, and waxing and waning disease activity within affected individuals [10, 11, 38]. FGF23 concentrations are normal during quiescent periods when serum phosphate levels are normal, whereas FGF23 levels are elevated during active, hypophosphatemic phases of disease [28]. Variable FGF23 levels and ADHR disease activity in the setting of germ-line FGF23 mutations suggested presence of additional regulators of FGF23 beyond classic feedback loops.

Several clues pointed to iron deficiency as an environmental trigger that modifies FGF23 expression and hence disease activity in ADHR. Clinical flares of ADHR often coincide with onset of puberty, menses and the maternal post-partum period when iron deficiency is common [11]. Human studies demonstrated inverse correlations between iron stores and serum phosphate and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D concentrations in patients with ADHR, but not in healthy controls [39]. Furthermore, lower serum iron levels in ADHR patients correlated significantly with higher FGF23 concentrations measured with either iFGF23 or cFGF23 assays, whereas low serum iron and ferritin concentrations correlated only with elevated cFGF23 but not iFGF23 levels in individuals with wild-type Fgf23 [36, 39]. Concordant with these findings, iron deficiency was associated with elevated cFGF23 in African children, including some with rickets [40, 41]. The consistent findings of high cFGF23 in association with iron deficiency, and variably elevated iFGF23 and cFGF23 levels that track with ADHR disease activity suggested novel mechanisms of FGF23 regulation by iron that are modified by Fgf23 genotype.

Experimental studies uncover a role of iron in FGF23 regulation

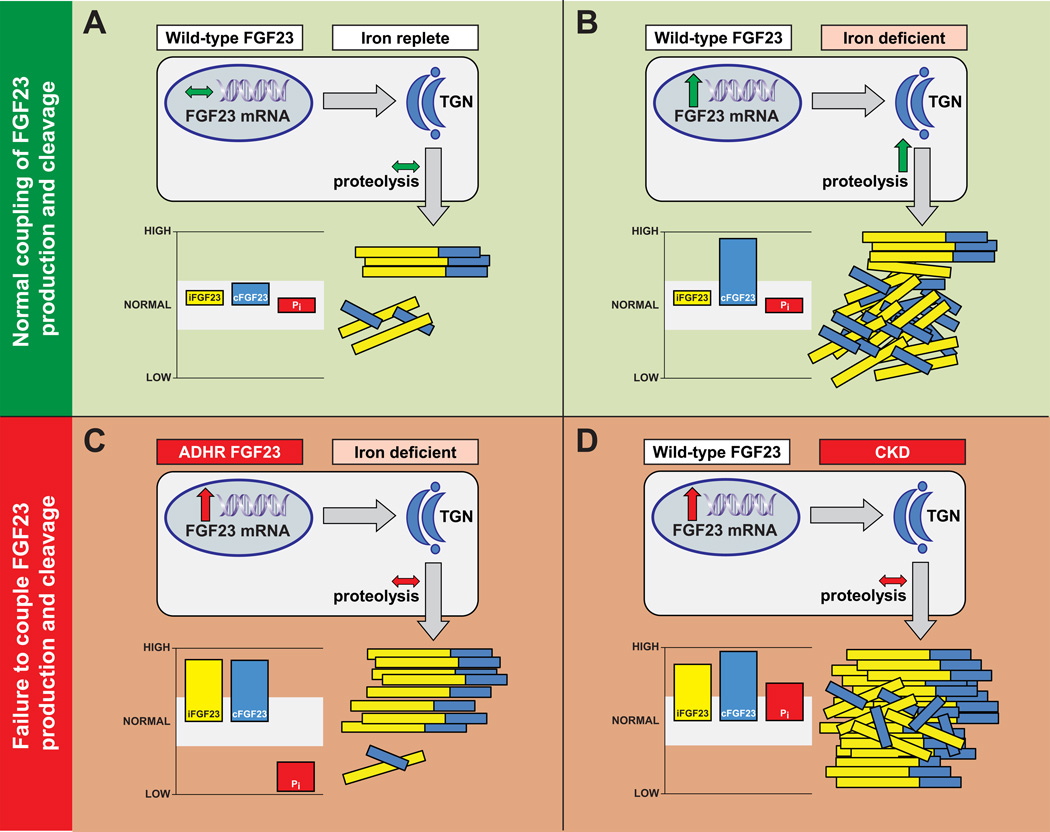

Studies in wild-type mice and mice carrying a knock-in ADHR mutant form of FGF23 (R176Q-FGF23; ADHR mice) brought to light the molecular connections between iron and FGF23 [42]. Bone expression of FGF23 mRNA and protein increased significantly in both wild-type and ADHR mice that consumed an iron-deficient diet compared to a control diet (Figure 2A, B). Confirmatory in vitro studies using the osteoblastic cell line UMR-106 demonstrated that iron chelation with deferoxamine increased FGF23 mRNA expression by 20-fold in association with stabilization of hypoxia inducible factor-1α-(HIF-1α) [42]. Interestingly, wild-type mice consuming the low-iron diet maintained normal serum iFGF23 and phosphate concentrations, but displayed markedly elevated cFGF23 levels (Figure 2B). This suggested a second level of FGF23 control within osteocytes whereby mature FGF23 protein is cleaved to maintain normal circulating levels of biologically active FGF23 in the face of increased FGF23 production. As a result of this ‘active’ processing of FGF23, normal phosphate homeostasis was maintained in wild-type mice consuming low or normal iron diets and in ADHR mice consuming a normal iron diet [42]. In contrast, ADHR mice that consumed the iron-deficient diet manifested elevated iFGF23 levels in addition to elevated cFGF23 levels (Figure 2C). As a result, the iron-deficient ADHR mice developed hypophosphatemia, osteomalacia and other pathogenic changes known to be associated with increased FGF23 activity, including detectable p-ERK1/2 signaling that co-localized with α-Klotho expression in the kidney, reduced renal NPT2a expression, and decreased Cyp27b1 and increased Cyp24a1 mRNA expression [42].

Figure 2. Intact coupling or failure to couple FGF23 production and cleavage in different clinical settings.

(A) In osteocytes of iron-replete humans and mice carrying wild type FGF23 alleles (RXXR in the subtilisin-like proprotein convertase site), normal production of FGF23 mRNA and protein is balanced by a commensurate amount of FGF23 cleavage in the trans-Golgi network (TGN). Normal coupling of FGF23 production and cleavage in this setting maintains iFGF23, cFGF23 and serum phosphate (Pi) levels within the normal range (shaded white).

(B) Osteocytes markedly increase FGF23 transcription in response to iron deficiency (or hypoxia), but in normal individuals, the excess FGF23 protein is proteolytically cleaved within the TGN. This maintains normal circulating concentrations of biologically active intact FGF23 and normal serum phosphate levels, but leaves behind high levels of inactive FGF23 fragments that register as high cFGF23 levels.

(C) In ADHR patients and ADHR mice, the mutant FGF23 (R176Q) is less susceptible to proteolytic cleavage. When iron deficiency stimulates increased production of FGF23 mRNA and protein, hypophosphatemia and osteomalacia result from increased circulating concentrations of biologically active, intact FGF23 that is detectable by both the iFGF23 and cFGF23 assays.

(D) In patients with CKD, FGF23 cleavage is down regulated or impaired, creating a functional state similar to ADHR. In the setting of iron deficiency, which is common in CKD, failure to adequately couple FGF23 cleavage to the magnitude of increase in FGF23 production results in increased circulating concentrations of biologically active intact FGF23 that is detectable by both the iFGF23 and cFGF23 assays. Serum phosphate is high or remains normal despite elevated FGF23 levels because renal phosphate excretion is impaired in CKD. Through unknown mechanisms, certain intravenous iron formulations also appear to induce a functional state similar to ADHR that can lead to hypophosphatemia when kidney function is intact.

In another study, breeding mice were fed an iron-deficient diet during the third week of pregnancy (to mimic the human third trimester when iron deficiency is common) and during pup nursing [43]. Both the neonatal ADHR and wild-type mice demonstrated significantly increased iFGF23 and hypophosphatemia. Although the ADHR mice had a more severe biochemical phenotype, as expected due to their cleavage-resistant Fgf23 mutation, it is not clear why neonatal but not adult wild-type mice develop elevated iFGF23 and hypophosphatemia in response to iron deficiency. Perhaps an immature FGF23 cleavage system in neonates can be overwhelmed by the increased amounts of FGF23 that are produced in response to iron deficiency. Alternatively, neonates could regulate circulating FGF23 protein differently than adults.

Hypoxia can also stimulate FGF23 production, independently of iron. UMR-106 cells grown in the presence of reduced oxygen tension but normal iron concentrations also demonstrated increased FGF23 mRNA expression. Similar to iron deficient wild-type mice, wild-type Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to hypoxia for two weeks demonstrated >6-fold increases in cFGF23 compared to control rats exposed to normal oxygen tension, but no significant changes in iFGF23 or serum phosphate levels [43].

In aggregate, these results demonstrate that iron deficiency and hypoxia increase bone expression of FGF23 mRNA and FGF23 protein. Mice that express wild-type FGF23 are capable of maintaining normal phosphate homeostasis by cleaving excessive amounts of the newly synthesized FGF23 protein into inactive N-terminal and C-terminal fragments so that circulating levels of biologically active FGF23 remain unchanged (Figure 2B). In this setting, high concentrations of fragments register as high cFGF23 levels, whereas iFGF23 levels remain normal. However, when iron deficiency stimulates expression of cleavage-resistant, ADHR-mutant FGF23, hypophosphatemia results from persistently elevated concentrations of biologically active FGF23 that register as high cFGF23 and high iFGF23 levels (Figure 2C).

A randomized trial confirms the role of iron in FGF23 regulation in humans

Women with iron deficiency anemia due to heavy uterine bleeding who were otherwise healthy were recruited into a randomized controlled clinical trial that compared two different preparations of intravenous iron [44]. At baseline, the iron deficient women demonstrated normal levels of serum phosphate, calcium, 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and iFGF23 (28.5 ± 1.1 pg/ml), but markedly elevated cFGF23 levels (807.8 ± 123.9 RU/ml) that correlated with the severity of iron deficiency. Thus, iron deficient women manifest a biochemical profile that is similar to iron deficient, wild-type animals, including lack of a phosphate phenotype and isolated elevation of cFGF23 levels (Figure 2B).

The women were randomly assigned to treatment with a single high dose of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose or iron dextran that provided equivalent doses of elemental iron [44]. Following intravenous iron repletion, cFGF23 levels fell by approximately 80% within 24 hours. This provided evidence in humans that iron deficiency causes cFGF23 levels to rise, and its correction can rapidly lower cFGF23 levels. Interestingly, the two specific iron formulations yielded diverging results for iFGF23. Whereas iFGF23 and other mineral metabolites did not change significantly in response to iron dextran, 10 of the 17 women who received ferric carboxymaltose developed transient but significant increases in iFGF23 that was subsequently associated with urinary phosphate wasting, hypophosphatemia, reduced 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D and calcium levels, and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Thus, exposure to ferric carboxymaltose transiently recapitulated the biochemical profile of ADHR despite concomitantly reducing cFGF23 levels by restoring normal iron stores.

Similar FGF23-mediated, acute, phosphate-wasting syndromes have been observed following administration of intravenous saccharated ferric oxide and iron polymaltose [45–49]. (Interestingly, no reports have implicated oral iron preparations). Although it is unknown why certain intravenous iron formulations increase iFGF23 levels, one hypothesis proposes that these agents disrupt the fine balance between FGF23 production and cleavage within osteocytes that was initially described in wild-type and ADHR-mutant mice fed different iron-containing diets [44]. Correcting iron deficiency with iron dextran rapidly decreased concentrations of C-terminal FGF23 fragments without changing intact hormone levels, consistent with decreased FGF23 production and conserved coupling of FGF23 production and cleavage. In contrast, culprit iron formulations may uncouple FGF23 production and cleavage by reducing cleavage to a greater extent than production, resulting in a transient hypophosphatemic syndrome that is similar biochemically to ADHR.

Hypothesis to explain elevated FGF23 levels in kidney disease

Due to its high prevalence, CKD is likely the most common cause of chronically elevated cFGF23 and iFGF23 levels [12, 50]. Although it is tempting to assume that hyperphosphatemia is the primary stimulus of elevated FGF23 in CKD, there is limited evidence to support a direct effect of phosphate on osteocyte FGF23 production [51], and FGF23 levels rise in CKD before serum phosphate is increased [14] and before phosphate balance becomes positive [52]. Other known stimulators of FGF23 include elevated 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D and PTH levels [53, 54]. However, 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D levels fall and PTH levels rise in CKD as downstream consequences of elevated FGF23 [13]. Levels of cFGF23 and iFGF23 also rise rapidly and dramatically soon after onset of acute kidney injury (AKI), independently of phosphate, 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D and PTH [55]. Thus, the classical stimuli of FGF23 production do not appear to adequately explain why cFGF23 and iFGF23 levels rise in states of acute and chronic kidney dysfunction.

We propose that CKD is an acquired state that mimics the molecular pathophysiology observed in ADHR and intravenous iron-induced hypophosphatemia (Figure 2D). As CKD progresses, FGF23 production increases in bone [56, 57], total FGF23 levels rise [14, 18], but the fraction of circulating FGF23 fragments declines so that the iFGF23:cFGF23 ratio approaches one [58], similar to ADHR (Figure 1B). By the time patients reach end-stage renal disease, virtually all circulating FGF23 is biologically intact [59], which is especially noteworthy given the astronomical levels often observed in this population (FGF23 >300,000 RU/ml in patients with end-stage renal disease are the highest that have been recorded in humans [60]). These findings suggest that FGF23 production is increased and FGF23 cleavage is relatively decreased in CKD. If FGF23 cleavage is indeed constitutively down-regulated in CKD, then factors that stimulate FGF23 production, such as iron deficiency, would be expected to increase circulating levels of intact FGF23 hormone, similar to ADHR (Figure 2D). Thus, we postulate that iron deficiency, which can affect >70% of individuals with estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73m2 [61], could be a novel mechanism that contributes to elevated FGF23 levels in CKD.

The uncoupling hypothesis could also explain other poorly understood observations regarding FGF23 in states of kidney injury. In AKI, cFGF23 and iFGF23 levels rise within 1 hour of injury [55]. Although bone production of FGF23 is increased in AKI [55], such a rapid rise in circulating levels cannot be explained solely by increased transcription. Perhaps osteocytes rapidly release preformed FGF23 in response to AKI. Perhaps ectopic production of FGF23 increases in AKI. Alternatively, if FGF23 is continuously produced and degraded by osteocytes, immediate cessation of proteolytic cleavage induced by kidney injury could explain a rapid increase in total FGF23 levels that is accompanied by a reduction in circulating concentrations of FGF23 fragments. This hypothesis could also explain the observation that FGF23 levels rose significantly in a mouse model of CKD compared to control animals long before an increase in FGF23 mRNA expression was detectable in bone [57]. We acknowledge that several studies that investigated iron status and different forms of intravenous iron therapy in uremic rats and in human CKD reported results that could be construed as being at odds with our hypothesis [45–49]. However, these studies should be interpreted with caution because they variably measured iFGF23 or cFGF23 but rarely both. Intensive investigation is needed to scrutinize and refute or refine our hypothesis.

Implications for treatment and future research

Individuals with FGF23-associated disorders in which there is incomplete coupling of FGF23 production and cleavage may benefit from screening for and correcting iron deficiency. For example, in patients with ADHR, oral iron formulations that correct iron deficiency but do not elevate iFGF23 levels may offer benefits above current standard-of-care that includes oral supplementation with phosphate and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D. These approaches are only partially effective and often complicated by secondary hyperparathyroidism and nephrocalcinosis [62]. Maintaining normal iron stores in the peripartum period may also promote healthy skeletal development in neonates who may not be capable of fully coupling iron deficiency-mediated increases in FGF23 production with commensurate FGF23 cleavage. Clinical trials should determine if oral iron supplementation will lower FGF23 levels and attenuate phosphate wasting in ADHR and improve skeletal health in susceptible neonates.

Additional research is needed to investigate the mechanism of FGF23 proteolysis within osteocytes and to what extent peripheral production and degradation of FGF23 contribute to circulating levels. This line of investigation could be especially relevant to CKD given its public health importance, high prevalence of iron deficiency, and high levels of FGF23 that may predispose to high risks of cardiovascular disease and death. Like ADHR, oral iron supplementation could also have a role in lowering FGF23 levels in CKD. Although long considered to be ineffective in CKD, ferric citrate, a novel iron-based phosphate binder, demonstrated enough gastrointestinal iron absorption to replete iron stores while reducing requirements for intravenous iron in patients with end-stage renal disease [63]. Preliminary studies suggest that this agent also lowers FGF23 levels significantly in CKD [64], perhaps because it simultaneously blunts classical stimuli of FGF23 production (by reducing dietary phosphate absorption) and novel stimuli (by correcting iron deficiency).

Conclusions

Despite major advances in our understanding of FGF23 biology, fundamental questions about its regulation remain unanswered. Recent studies involving animal models and humans demonstrate that iron deficiency and hypoxia regulate FGF23 mRNA production in bone. In normal adults with intact coupling of FGF23 production and cleavage in osteocytes, excess FGF23 protein is cleaved into inactive fragments. As a result, iron deficiency does not disturb phosphate homeostasis and leaves behind only a footprint of high cFGF23 levels. In contrast, ADHR, the fetal peripartum period, and certain intravenous iron formulations partially or completely uncouple FGF23 cleavage from FGF23 production, resulting in susceptibility to elevated levels of biologically active FGF23 hormone and phosphate wasting. These findings establish proteolytic cleavage of newly synthesized FGF23 in osteoctyes as a second important step in FGF23 regulation beyond transcriptional control. They advance a novel framework for additional investigation of mechanisms of FGF23 elevation in CKD, and most importantly, suggest important new avenues for potential therapeutic interventions.

Key points.

Iron deficiency stimulates FGF23 transcription.

In the setting of iron deficiency, healthy humans and mice maintain normal phosphate homeostasis by coupling increased FGF23 production to commensurately increased proteolytic cleavage of FGF23.

Iron deficiency induces hypophosphatemia in ADHR because the stabilizing FGF23 mutations prevent increased FGF23 cleavage in the setting of increased production.

Since CKD may be an acquired state of down-regulated FGF23 cleavage that mimics the molecular pathophysiology of ADHR, iron deficiency may be a novel mechanism of FGF23 elevation in CKD.

FGF23 production and FGF23 cleavage are two distinct levels of FGF23 control within osteocytes that regulate circulating FGF23 levels.

Acknowledgements

disclosure

MW is supported by grants R01DK076116, R01DK081374, R01DK094796, K24DK093723, and U01DK099930 from the National Institutes of Health.

KW is supported by grants DK063934 and DK95784 from the National Institutes of Health; the Indiana Genomic Initiative (INGEN) of Indiana University supported in part by the Lilly Endowment, Inc.; and as an inaugural Showalter Scholar through the Ralph W. and Grace M. Showalter Research Trust Fund.

MW has received research support, honoraria or consultant fees from Amgen, Genzyme, Keryx, Luitpold, Opko, Pfizer, Shire and Vifor.

KW has received research support from Eli Lilly and Co., and Sanofi-Genzyme.

References

- 1.ADHR-Consortium. Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations in FGF23. Nat Genet. 2000;26:345–348. doi: 10.1038/81664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimada T, Mizutani S, Muto T, Yoneya T, Hino R, Takeda S, et al. Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6500–6505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101545198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsson T, Marsell R, Schipani E, Ohlsson C, Ljunggren O, Tenenhouse HS, et al. Transgenic mice expressing fibroblast growth factor 23 under the control of the alpha1(I) collagen promoter exhibit growth retardation, osteomalacia, and disturbed phosphate homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3087–3094. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnett SM, Gunawardene SC, Bringhurst FR, Juppner H, Lee H, Finkelstein JS. Regulation of C-terminal and intact FGF-23 by dietary phosphate in men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1187–1196. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoniucci DM, Yamashita T, Portale AA. Dietary phosphorus regulates serum fibroblast growth factor-23 concentrations in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3144–3149. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perwad F, Azam N, Zhang MY, Yamashita T, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. Dietary and serum phosphorus regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 expression and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D metabolism in mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5358–5364. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gribaa M, Younes M, Bouyacoub Y, Korbaa W, Ben Charfeddine I, Touzi M, et al. An autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets phenotype in a Tunisian family caused by a new FGF23 missense mutation. J Bone Miner Metab. 2010;28:111–115. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White KE, Carn G, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Benet-Pages A, Strom TM, Econs MJ. Autosomal-dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) mutations stabilize FGF-23. Kidney Int. 2001;60:2079–2086. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada T, Muto T, Urakawa I, Yoneya T, Yamazaki Y, Okawa K, et al. Mutant FGF-23 responsible for autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets is resistant to proteolytic cleavage and causes hypophosphatemia in vivo. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3179–3182. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bianchine JW, Stambler AA, Harrison HE. Familial hypophosphatemic rickets showing autosomal dominant inheritance. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1971;7:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Econs MJ, McEnery PT. Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia: clinical characterization of a novel renal phosphate-wasting disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:674–681. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf M. Forging forward with 10 burning questions on FGF23 in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1427–1435. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasegawa H, Nagano N, Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Iijima K, Fujita T, et al. Direct evidence for a causative role of FGF23 in the abnormal renal phosphate handling and vitamin D metabolism in rats with early-stage chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2010;78:975–980. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, Gutierrez OM, Scialla J, Xie H, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1370–1378. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker BD, Schurgers LJ, Brandenburg VM, Christenson RH, Vermeer C, Ketteler M, et al. The associations of fibroblast growth factor 23 and uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein with mortality in coronary artery disease: the Heart and Soul Study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:640–648. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B, Hu MC, Sloan A, Isakova T, et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4393–4408. doi: 10.1172/JCI46122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, Xie D, Anderson AH, Scialla J, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA. 2011;305:2432–2439. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf M, Molnar MZ, Amaral AP, Czira ME, Rudas A, Ujszaszi A, et al. Elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 is a risk factor for kidney transplant loss and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:956–966. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendrick J, Cheung AK, Kaufman JS, Greene T, Roberts WL, Smits G, et al. FGF-23 associates with death, cardiovascular events, and initiation of chronic dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1913–1922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scialla JJ, Xie H, Rahman M, Anderson AH, Isakova T, Ojo A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and cardiovascular events in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:349–360. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050465. In this prospective cohort study of patients with CKD stages 2–4, higher FGF23 levels were independently associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease events, and elevated FGF23 was significantly more strongly associated with incident congestive heart failure than incident atherosclerotic events.

- 22. Ix JH, Katz R, Kestenbaum BR, de Boer IH, Chonchol M, Mukamal KJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and death, heart failure, and cardiovascular events in community-living individuals: CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.040. In this community-based prospective cohort study, higher FGF23 levels were independently associated with higher risks of death and cardiovascular disease events, particularly congestive heart failure. Presence of early CKD magnified these risks.

- 23.Gutierrez OM, Januzzi JL, Isakova T, Laliberte K, Smith K, Collerone G, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2009;119:2545–2552. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.844506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez OM, Wolf M, Taylor EN. Fibroblast growth factor 23, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and phosphorus intake in the health professionals follow-up study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2871–2878. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02740311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jean G, Terrat JC, Vanel T, Hurot JM, Lorriaux C, Mayor B, et al. High levels of serum fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 are associated with increased mortality in long haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2792–2796. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamazaki Y, Okazaki R, Shibata M, Hasegawa Y, Satoh K, Tajima T, et al. Increased circulatory level of biologically active full-length FGF-23 in patients with hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4957–4960. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonsson KB, Zahradnik R, Larsson T, White KE, Sugimoto T, Imanishi Y, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 in oncogenic osteomalacia and X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1656–1663. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imel EA, Hui SL, Econs MJ. FGF23 concentrations vary with disease status in autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:520–526. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Topaz O, Shurman DL, Bergman R, Indelman M, Ratajczak P, Mizrachi M, et al. Mutations in GALNT3, encoding a protein involved in O-linked glycosylation, cause familial tumoral calcinosis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:579–581. doi: 10.1038/ng1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ichikawa S, Sorenson AH, Austin AM, Mackenzie DS, Fritz TA, Moh A, et al. Ablation of the Galnt3 gene leads to low-circulating intact fibroblast growth factor 23 (Fgf23) concentrations and hyperphosphatemia despite increased Fgf23 expression. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2543–2550. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichikawa S, Baujat G, Seyahi A, Garoufali AG, Imel EA, Padgett LR, et al. Clinical variability of familial tumoral calcinosis caused by novel GALNT3 mutations. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:896–903. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benet-Pages A, Orlik P, Strom TM, Lorenz-Depiereux B. An FGF23 missense mutation causes familial tumoral calcinosis with hyperphosphatemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:385–390. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsson T, Davis SI, Garringer HJ, Mooney SD, Draman MS, Cullen MJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 mutants causing familial tumoral calcinosis are differentially processed. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3883–3891. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsson T, Yu X, Davis SI, Draman MS, Mooney SD, Cullen MJ, et al. A novel recessive mutation in fibroblast growth factor-23 causes familial tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2424–2427. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frishberg Y, Ito N, Rinat C, Yamazaki Y, Feinstein S, Urakawa I, et al. Hyperostosis-hyperphosphatemia syndrome: a congenital disorder of O-glycosylation associated with augmented processing of fibroblast growth factor 23. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:235–242. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durham BH, Joseph F, Bailey LM, Fraser WD. The association of circulating ferritin with serum concentrations of fibroblast growth factor-23 measured by three commercial assays. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44:463–466. doi: 10.1258/000456307781646102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imel EA, Peacock M, Pitukcheewanont P, Heller HJ, Ward LM, Shulman D, et al. Sensitivity of fibroblast growth factor 23 measurements in tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2055–2061. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Econs MJ, McEnery PT, Lennon F, Speer MC. Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets is linked to chromosome 12p13. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2653–2657. doi: 10.1172/JCI119809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Imel EA, Peacock M, Gray AK, Padgett LR, Hui SL, Econs MJ. Iron modifies plasma FGF23 differently in autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets and healthy humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3541–3549. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1239. Patients with ADHR had elevated iFGF23 and cFGF23 levels that correlated inversely with serum iron concentrations, whereas only cFGF23 correlated inversely with serum iron in control individuals. Longitudinally, reduced serum phosphate and 1,25D correlated with lower serum iron in ADHR, suggesting a link between iron deficiency and ADHR disease activity.

- 40.Braithwaite V, Jarjou LM, Goldberg GR, Prentice A. Iron status and fibroblast growth factor-23 in Gambian children. Bone. 2012;50:1351–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Braithwaite V, Jarjou LM, Goldberg GR, Jones H, Pettifor JM, Prentice A. Follow-up study of Gambian children with rickets-like bone deformities and elevated plasma FGF23: possible aetiological factors. Bone. 2012;50:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Farrow EG, Yu X, Summers LJ, Davis SI, Fleet JC, Allen MR, et al. Iron deficiency drives an autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) phenotype in fibroblast growth factor-23 (Fgf23) knock-in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E1146–E1155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110905108. This translational study defined the molecular mechanisms linking iron deficiency and FGF23. Low iron diet markedly increased bone transcription of Fgf23 in mice. In normal mice, the excessive amounts of mature FGF23 hormone were proteolytically cleaved to maintain normal circulating iFGF23 levels and thus, normal phosphate homeostasis. In knock-in mice carrying the R176Q-FGF23 ADHR mutation that is resistant to proteolysis, iron deficiency resulted in elevated iFGF23 and hypophosphatemic osteomalacia. This paper was the first to identify FGF23 production and cleavage within osteocytes as two distinct levels of FGF23 regulation.

- 43. Clinkenbeard EL, Farrow EG, Summers LJ, Cass TA, Roberts JL, Bayt CA, et al. Neonatal iron deficiency causes abnormal phosphate metabolism by elevating FGF23 in normal and ADHR Mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:361–369. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2049. Both ADHR and WT pups born to female mouse breeders that were fed low iron diets during pregnancy developed a hypophosphatemic phenotype at weaning that was more severe in the ADHR mice. This study demonstrated that FGF23 has a critical role in phosphate metabolism during the neonatal period and suggests that FGF23 may be differentially processed early in life. The study also provided the first evidence that hypoxia, independent of iron deficiency, could increase FGF23 production by cultured bone cells in vitro and in normal rats in vivo.

- 44. Wolf M, Koch TA, Bregman DB. Effects of iron deficiency anemia and its treatment on fibroblast growth factor 23 and phosphate homeostasis in women. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1793–1803. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1923. In this randomized controlled trial, iron-deficient women demonstrated markedly elevated cFGF23 but normal iFGF23 and serum phosphate levels at baseline. Both intravenous iron formulations rapidly lowered cFGF23 levels, but only one of the agents simultaneously raised iFGF23 and caused hypophosphatemia. This was the first human experimental study to demonstrate that iron deficiency reversibly stimulates FGF23 production. It also highlighted production and cleavage as two distinct levels of FGF23 regulation.

- 45.Gravesen E, Hofman-Bang J, Mace ML, Lewin E, Olgaard K. High dose intravenous iron, mineral homeostasis and intact FGF23 in normal and uremic rats. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prats M, Font R, Garcia C, Cabre C, Jariod M, Vea AM. Effect of ferric carboxymaltose on serum phosphate and C-terminal FGF23 levels in non-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients: post-hoc analysis of a prospective study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hryszko T, Rydzewska-Rosolowska A, Brzosko S, Koc-Zorawska E, Mysliwiec M. Low molecular weight iron dextran increases fibroblast growth factor-23 concentration, together with parathyroid hormone decrease in hemodialyzed patients. Ther Apher Dial. 2012;16:146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2011.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeda Y, Komaba H, Goto S, Fujii H, Umezu M, Hasegawa H, et al. Effect of intravenous saccharated ferric oxide on serum FGF23 and mineral metabolism in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2011;33:421–426. doi: 10.1159/000327019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deger SM, Erten Y, Pasaoglu OT, Derici UB, Reis KA, Onec K, et al. The effects of iron on FGF23-mediated Ca-P metabolism in CKD patients. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:416–423. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0725-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolf M. Update on fibroblast growth factor 23 in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012;82:737–747. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu S, Tang W, Zhou J, Stubbs JR, Luo Q, Pi M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is a counter-regulatory phosphaturic hormone for vitamin D. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1305–1315. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005111185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hill KM, Martin BR, Wastney ME, McCabe GP, Moe SM, Weaver CM, et al. Oral calcium carbonate affects calcium but not phosphorus balance in stage 3–4 chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;83:959–966. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.403. Among the many important findings in this classic balance study, FGF23 levels were already elevated in CKD patients with neutral phosphate balance and normal serum phosphate levels, suggesting presence of other important regulators of elevated FGF23 levels in early CKD.

- 53.Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, Muto T, Hino R, Takeuchi Y, et al. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:429–435. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rhee Y, Bivi N, Farrow E, Lezcano V, Plotkin LI, White KE, et al. Parathyroid hormone receptor signaling in osteocytes increases the expression of fibroblast growth factor-23 in vitro and in vivo. Bone. 2011;49:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Christov M, Waikar SS, Pereira RC, Havasi A, Leaf DE, Goltzman D, et al. Plasma FGF23 levels increase rapidly after acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013;84:776–785. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.150. This study demonstrated that both iFGF23 and cFGF23 levels dramatically soon after renal injury in human and rodent AKI, independently of classic stimuli of FGF23 production. The rapidity of the increase in both iFGF23 and cFGF23 argues against increased transcription as the sole mechanism, and suggests a second level of FGF23 regulation, perhaps, decreased cleavage.

- 56.Pereira RC, Juppner H, Azucena-Serrano CE, Yadin O, Salusky IB, Wesseling-Perry K. Patterns of FGF-23, DMP1, and MEPE expression in patients with chronic kidney disease. Bone. 2009;45:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stubbs JR, He N, Idiculla A, Gillihan R, Liu S, David V, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of FGF23 changes and mineral metabolism abnormalities in a mouse model of chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:38–46. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.516. In this longitudinal assessment of mineral metabolism in a mouse model of CKD, circulating FGF23 levels were significantly elevated before increases in bone transcription of FGF23 could be detected. This suggests that additional mechanisms beyond increased production account for elevated circulating FGF23 levels in CKD.

- 58. Smith ER, Cai MM, McMahon LP, Holt SG. Biological variability of plasma intact and C-terminal FGF23 measurements. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3357–3365. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1811. Total FGF23 levels were lowest in healthy volunteers, higher in intermediate-stage CKD, highest in end-stage renal disease. However, Western blotting demonstrated that the fraction of C-terminal FGF23 fragments relative to total circulating FGF23 was highest in healthy volunteers, lower in CKD, and lowest in end-stage renal disease. This demonstrates that levels of biologically active FGF23 increase and represent a growing fraction of circulating FGF23 species as CKD progresses. It also suggests that FGF23 cleavage in osteocytes is decreased in CKD.

- 59.Shimada T, Urakawa I, Isakova T, Yamazaki Y, Epstein M, Wesseling-Perry K, et al. Circulating fibroblast growth factor 23 in patients with end-stage renal disease treated by peritoneal dialysis is intact and biologically active. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:578–585. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isakova T, Xie H, Barchi-Chung A, Vargas G, Sowden N, Houston J, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2688–2695. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04290511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fishbane S, Pollack S, Feldman HI, Joffe MM. Iron indices in chronic kidney disease in the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey 1988–2004. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:57–61. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01670408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carpenter TO. The expanding family of hypophosphatemic syndromes. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00774-011-0340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewis J, Dwyer JP, Koury M, Sika M, Schulman G, Smith MT, et al. Ferric citrate binds phosphorus, delivers iron, and reduces IV iron and erythropoietic stimulating agent use in end-stage renal disease [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yokoyama K, Hirakata H, Akiba T, Fukagawa M, Nakayama M, Sawada K, et al. Ferric citrate hydrate for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in nondialysis-dependent CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.2215/CJN.05170513. In this placebo-controlled randomized trial of CKD patients not yet requiring dialysis, the novel phosphate binder, ferric citrate, significantly increased iron stores, and significantly lowered serum phosphate and iFGF23 levels.