Abstract

Uterine decidualization, characterized by stromal cell proliferation, and differentiation into specialized type of cells (decidual cells) with polyploidy, during implantation is critical to the pregnancy establishment in mice. The mechanisms by which the cell cycle events govern these processes are poorly understood. The cell cycle is tightly regulated at two particular checkpoints, G1-S and G2-M phases. Normal operation of these phases involves a complex interplay of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) and cdk inhibitors (CKIs). We previously observed that upregulation of uterine cyclin D3 at the implantation site is tightly associated with decidualization in mice. To better understand the role of cyclin D3 in this process, we examined cell-specific expression and associated interactions of several cell cycle regulators (cyclins, cdks and CKIs) specific to different phases of the cell cycle during decidualization in mice. Among the various cell cycle molecules examined, coordinate expression and functional association of cyclin D3 with cdk4 suggest a role for proliferation and, that of cyclin D3 with p21 and cdk6 is consistent with the development of polyploidy during stromal cell decidualization.

Keywords: Cell cycle, Cyclin D3, P21, cdk6, Implantation, Polyploidy, Decidualization, Uterus, Mouse

1. Introduction

Synchronized development of the embryo to the active stage of the blastocyst, differentiation of the uterus to the receptive state, and a ‘cross talk’ between the blastocyst and uterine luminal epithelium are essential to the implantation process (Psychoyos, 1973; Dey, 1996). The initiation of implantation in mice is characterized by a localized uterine vascular permeability at the site of the blastocyst with the onset of the attachment reaction (blue reaction), occurring between 22:00 and 24:00 h on day 4 of pregnancy (day 1, plug positive). With the initiation of the attachment reaction, intense localized stromal cell proliferation occurs surrounding the implanting blastocyst. In contrast, luminal epithelial cells at the site of blastocyst apposition progressively undergo apoptosis with the progression of implantation. Between day 5 afternoon and day 6 morning, stromal cells immediately surrounding the implanting blastocyst at the antimesometrial pole cease proliferating and undergo differentiation into decidual cells, forming a zone termed the primary decidual zone (PDZ). The PDZ is avascular and epithelioid in nature. The cells at the PDZ subsequently undergo apoptosis and by day 8 most of these cells disappear. However, stromal cells next to the PDZ continue to proliferate and differentiate into polyploid decidual cells forming the secondary decidual zone (SDZ) (Dey, 1996). This pattern persists through days 7 and 8. Eventually the SDZ cells also undergo apoptosis enlarging the implantation chamber to accommodate the growing embryo.

In rodents, the development of decidual cells at the anti-mesometrial uterine bed occurs with the acquisition of polyploidization, a unique feature of decidualization. Furthermore, the antimesometrial decidualizing stroma is comprised of two populations of cells: one that proliferates before undergoing transformation and the second one that undergoes transformation without further division. The decidual cell polyploidy is characterized by the formation of large mono or bi-nucleated cells, a characteristic of nuclear endoreduplication, consisting of DNA with four, eight and even higher multiples of the haploid complement (Sachs and Shelesnyak, 1955; Ansell et al., 1974; Moulton, 1979). It is believed that endoreduplicated cells exhibit an array of cell cycle activities that direct continuous DNA synthesis without cell division (cytokinesis). In the uterus during decidualization, yet another cell cycle variant could be potentially active that triggers nuclear division without cytokinesis, giving rise to bi-nucleated cells. Such cycle events have been reported in mammalian hepatocytes and osteoclasts. Although several biological processes including cell differentiation, expansion and metabolic activity are associated with endoreduplication (Edgar and Orr-Weaver, 2001), the definitive physiological significance of this event in uterine decidualization remains poorly understood. Furthermore, the mechanism of decidual polyploidization largely remains unknown, although it is believed that the onset of stromal cell proliferation and differentiation is largely controlled at different stages of the cell cycle by various cell cycle regulatory molecules.

The cell cycle is a complex process and is primarily controlled by the interplay of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) (Roberts, 1999; Sherr and Roberts, 1999). The cellular growth is critically controlled at two particular transitions: G1-S and G2-M. Various cell cyclins mediate their actions as positive growth regulators during these transitions via association with specific cdks. The well-known regulators of mammalian cell proliferation are the three D-type cyclins (D1, D2 and D3) which are also known as G1 cyclins. The D-type cyclins accumulate during the G1 phase and their association with cdk4 or cdk6 is particularly important to form holoenzymes that facilitate cell entry into the S-phase. Retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and its family members, p107 and p130, are negative regulators of the D-type cyclins. Inactivation of these regulators by phosphorylation, dependent on the cyclin/cdk complex activity, allows the cell cycle progression through the G1 phase (Riley et al., 1994). The overexpression of D-type cyclins shortens G1 phase and allows rapid entry into S phase (Resnitzky et al., 1994). In contrast, cyclins A and B are involved in progression from S through G2-M phase. Binding of cyclin A or cyclin B to cdk1 induces phosphorylation and activation of the complex that is essential for the G2-M phase transition, while cyclin A/cdk2 complex is required during progression in the S phase. In general, the action of cdks is constrained by at least two families of CKI, p16 and p21. The p16 family includes p15, p16, p18 and p19, and they specifically inhibit the catalytic partners of D-type cyclins (cdk4 and cdk6). The p21 family consists of p21, p27 and p57, and they inhibit cdks with a broader specificity. It is well known that CKIs accumulate in quiescent cells, and are downregulated with the onset of proliferation. Thus, a critical balance between the positive and negative cell cycle regulators is the key decision-maker for cell division. Changes in the levels of D-type cyclins and cdk inhibitors normally occur when quiescent cells are stimulated by mitogenic signals. The general consensus is that the mitogenic signals should converge prior to the S phase entry of the cell, but the precise point of convergence and integration in the G1 phase remains unknown.

The uterus provides a unique and dynamic physiological model in which cellular proliferation, differentiation with polyploidization and apoptosis occur in a temporal and cell-specific manner during pregnancy. Although there is evidence to suggest that cell cycle regulatory molecules play potential roles in the uterus during steroid hormonal stimulation (Geum et al., 1997; Prall et al., 1997) and reproductive cycle (Shiozawa et al., 1998), and in trophoblast differentiation during placentation (Bamberger et al., 1999), very limited information is available regarding participation of uterine cell cycle molecules during implantation and decidualization. We provide here evidence that coordinate expression and functional interaction of cyclin D3 with cdk4 are important for proliferation, while that of cyclin D3 with p21 and cdk6 are important for development of polyploidy during stromal cell decidualization.

2. Results

2.1. G1-phase specific cell cycle regulators are differentially expressed in the periimplantation uterus

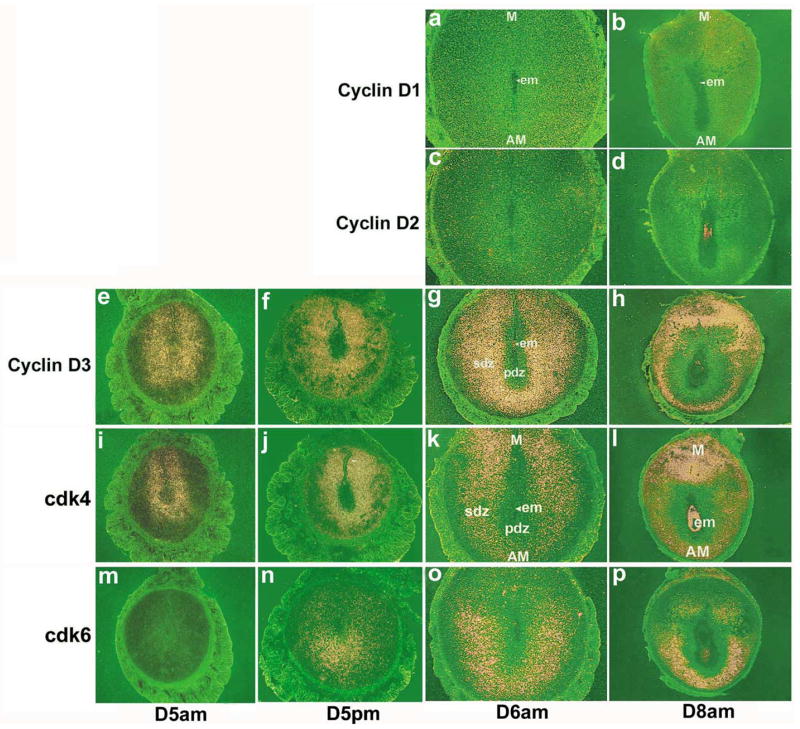

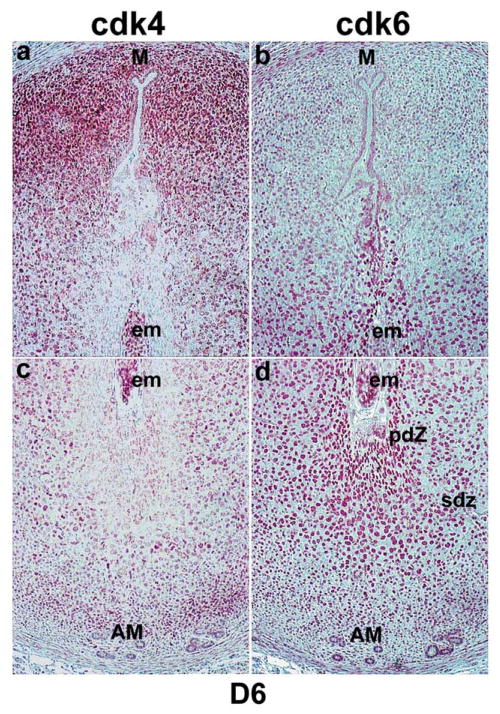

We previously observed that cyclin D3, a G1-phase cell cycle regulator, is expressed in the mouse uterus with the onset of implantation (Das et al., 1999). To determine the importance of other G1 phase specific cell cycle regulators, we examined their spatiotemporal expression in the uterus during implantation and decidualization. The expression of cyclin D1 and cyclin D2 was low in the uterus prior to and during decidualization. Representative expressions on days 6 and 8 of pregnancy are shown (Fig. 1a–d). In contrast, a remarkable expression of cyclin D3 was noted with the onset and progression of decidualization. As previously reported (Das et al., 1999), the uterine expression of cyclin D3 was very low on day 4 (data not shown). However, with the onset of implantation, cyclin D3 expression was primarily restricted to the decidualizing stroma surrounding the implanting blastocyst on day 5 (09:00 h) (Fig. 1e). With the formation of the PDZ on day 5 afternoon (18:00 h), increased expression was noted in cells out side the PDZ (Fig. 1f). In contrast, on days 6 (Fig. 1g) and 7 (data not shown) the localization was primarily restricted to the antimesometial SDZ. On day 8, the signals in the antimesometrial SDZ decreased, but became more intense in cells at the mesometrial pole (Fig. 1h). Functions of D-type cyclins are dependent on the presence of cdk4 and cdk6. Our in situ hybridization data demonstrate that the expression of cdk4 and cdk6 are differentially expressed in the periimplantation uterus (Fig. 1). While the expression of cdk4 mRNA was very low in stromal cells on day 4 (data not shown), the expression was upregulated in stromal cells surrounding the embryo both at the mesometrial and antimesometrial poles on day 5 (09:00 and 18:00 h) (Fig. 1i,j, respectively). However, the expression was downregulated in PDZ in the afternoon of day 5 (Fig. 1j). On day 6, the expression was predominantly upregulated in the mesometrial pole with reduced antimesometrial expression (Fig. 1k). A similar distribution was also noted on day 7 (data not shown). On day 8, heightened expression was noted in cells at the mesometrial pole, while low accumulation of mRNA still persisted in stromal cells at the antimesometrial pole (Fig. 1l). With respect to cdk6, uterine expression was undetectable on day 4 (data not shown) and 5 (09:00 h) (Fig. 1m). However, accumulation of mRNA was noted primarily at the antimesometial pole in the afternoon (18:00 h) on day 5 of pregnancy (Fig. 1n). However, on days 6 (Fig. 1o) and 7 (data not shown), a strong accumulation of cdk6 mRNA was noted in the decidualizing stroma at the antimesometrial pole. On day 8, a more intense expression was primarily observed at the antimesometrial deciduum (Fig. 1p). Overall, these results suggest that cyclin D3, cdk4 and cdk6, but not cyclins D1 and D2, are upregulated at the site of implantation during stromal cell decidualization.

Fig. 1.

In situ hybridization of cyclins D1-D3, cdk4 and cdk6 mRNAs in the mouse implantation sites. Frozen sections (10 μm) were mounted onto poly-L-lysine coated slides and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The sections were hybridized with 35S-labeled sense or antisense riboprobes for 4 h at 45°C. RNase A resistant hybrids were detected after 5–7 days of autoradiography using Kodak NTB-2 liquid emulsion. Sections were post-stained lightly with hematoxylin and eosin. Dark-field photomicrographs of representative cross-sections are shown on day 5 at 09:00 h (D5am) and at 18:00 h (D5pm), and on days 6 (D6am) and 8 (D8am) at 09:00 h of pregnancy. Magnifications are shown at 40 × for days 5–6 pregnancy and at 20 × for day 8 of pregnancy. M, mesometrial pole; AM, antimesometrial pole; em, embryo; PDZ, primary decidual zone; SDZ, secondary decidual zone. Sections hybridized with the corresponding sense probes did not show any positive signals (data not shown).

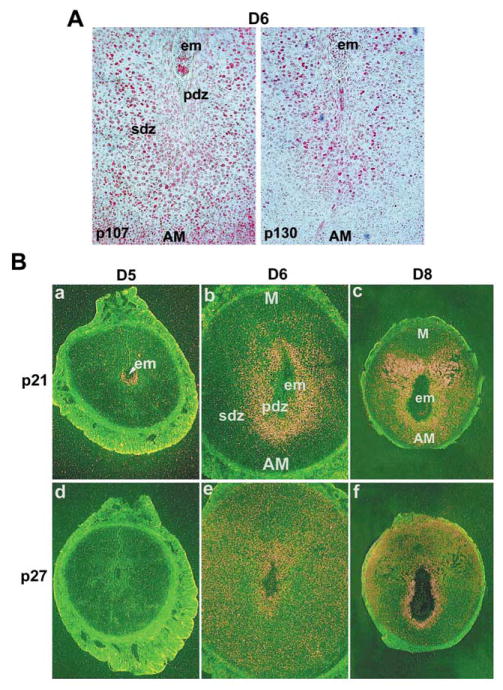

Since the members of the Rb family negatively control the actions of D-type cyclin, we examined their expression during decidualization. The results show that the Rb expression is undetectable in the deciduum (data not shown). Our failure to detect Rb suggests that this is a unique situation where Rb is not obligatory for functional regulation of cyclin D3. Alternatively, it is possible that other members of the Rb family, such as p107 and p130, fulfil the functions of Rb. Indeed, our results show that p107 and p130 are expressed in decidual cells with polyploidy on days 6 (Fig. 2A) and 7 (data not shown) of pregnancy. Our next objective was to examine whether functional inhibitors of cdks are differentially expressed in the uterus during decidualization.

Fig. 2.

Analyses of cell cycle inhibitors at the implantation sites. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of p107 and p130 on D6 of pregnancy. Implantation sites at 09:00 h were fixed in formalin and paraffin embedded sections (6 μm) were mounted onto poly-L-lysine-coated slides. After deparaffinization and hydration, sections were incubated with primary antibody either for p107 or p130 in PBS for 17 h at 4°C. The photomicrographs of representative uterine sections are shown at 100 ×. Red nuclear staining indicates the localization of immunoreactive proteins. No immunostaining was noted when similar sections were incubated with the primary antibody pre-neutralized with excess antigen (data not shown). AM, antimesometrial pole; em, embryo; PDZ, primary decidual zone; SDZ, secondary decidual zone. (B) In situ hybridization of p21 and p27 mRNAs on D5, D6 and D8 of pregnancy. While dark-field photomicrographs of representative cross-sections on D5 and D6 are shown at 40 ×, representative cross-sections on D8 are shown at 20 ×. Sections hybridized with the corresponding sense probes did not show any specific signals (data not shown). M, mesometrial pole; AM, antimesometrial pole; em, embryo; PDZ, primary decidual zone; SDZ, secondary decidual zone.

Our in situ hybridization data show that the putative inhibitors of cdks, p21 and p27, are also expressed differentially in the uterus during periimplantation period (Fig. 2B). While the expression of p21 was undetectable in the uterus on day 4 (data not shown), the expression was distinctly localized in the antimesometrial luminal epithelium and the sub-luminal stroma at the site of implanting embryo in the morning (09:00 h) (Fig. 2Ba). However, in the afternoon (18:00 h) of day 5, the expression was detectable primarily in the PDZ (data not shown). On day 6, the stromal expression persisted in some cells in the PDZ and in a large number of SDZ cells immediately surrounding the PDZ (Fig. 2Bb). On day 7, the expression was primarily noted in SDZ cells (data not shown). On day 8, an increased expression was noted in cells at the mesometrial pole and in some decidual cells closer to the embryo at the antimesometrial pole (Fig. 2Bc). With respect to p27, no specific expression was noted in the uterus on days 4 (data not shown) and 5 (Fig. 2Bd) of pregnancy. In contrast, on days 6 (Fig. 2Be) and 7 (data not shown) of pregnancy, a scattered distribution of this mRNA was detected in some cells in the endometrium. On day 8, a distinct expression was observed primarily in the antimesometrial decidual cells immediately surrounding the embryo (Fig. 2Bf). These data suggest that p21 and p27 are differentially expressed in the periimplantation uterus with p21 expression closely associated with the onset of decidualization.

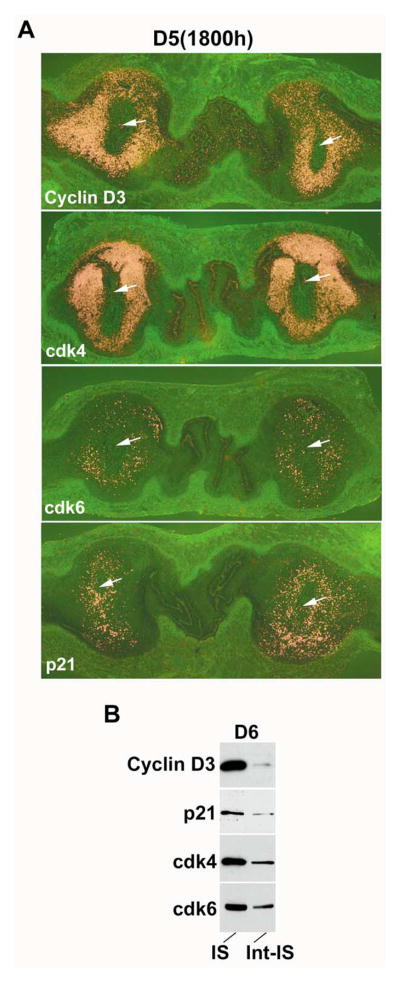

We next compared the differential expression patterns of cyclin D3, cdk4, cdk6 and p21 mRNAs between the implantation and inter-implantation sites by in situ hybridization of longitudinal uterine sections containing two implanting embryos on day 5 (18:00 h) of pregnancy. The results clearly show that the accumulation of mRNA for each of these genes in the inter-implantation region is either low or undetectable as compared to that observed at the implantation sites (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, heightened expression of mRNAs for cyclin D3, p21, cdk4 and cdk6 at the implantation site with the decidualizing stroma was also reflected at their protein levels on day 6 as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 3B). Our next objective was to examine whether accumulation of these proteins in decidual cells correlate with polyploidy.

Fig. 3.

(A) In situ hybridization for cyclin D3, cdk4, cdk6 and p21 mRNAs in the implantation and inter-implantation sites on day 5 (18:00 h) of pregnancy. Dark-field photomicrographs of longitudinal uterine sections containing two implanting embryos are shown at 20 ×. Arrows indicate the location of embryo in the implantation site. (B) Western blot analysis of cyclin D3, p21, cdk4 and cdk6 proteins in the mouse uterus on D6 of pregnancy. Implantation (IS) and interimplantation (Int-IS) sites were collected separately, and extracted and fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed using primary antibodies specific to cyclin D3, p21, cdk4 or cdk6. The primary antibodies and the protocol used for immunoblotting are described in Materials and Methods. For control experiments, primary antibodies pre-neutralized with 250-fold molar excess of corresponding antigenic peptide were used (data not shown).

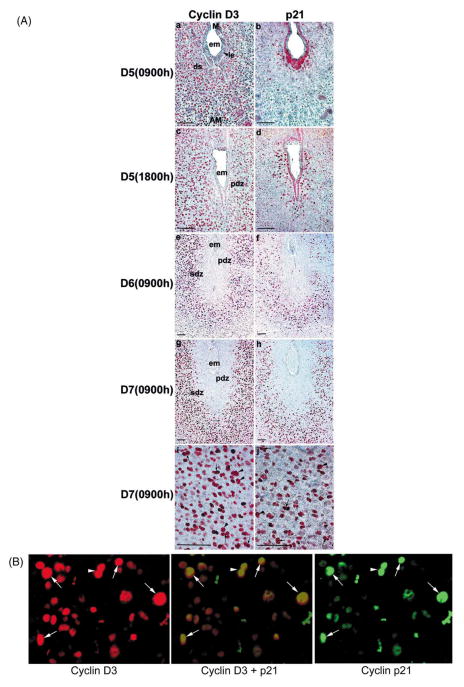

2.2. Coordinate expression of Cyclin D3 with p21 and cdk6 correlates with decidual cell polyploidy

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed nuclear localization of cyclin D3 in proliferating stromal cells immediately surrounding the implanting blastocyst on day 5 morning (Fig. 4Aa). However, with the progression of implantation in the afternoon of day 5, these cells ceased proliferating marking the formation of the PDZ. This reduced cell proliferation in the PDZ was accompanied by reduced accumulation of cyclin D3 (Fig. 4Ac). In contrast, nuclear localization of p21 showed different pattern. While few stromal cells surrounding the blastocyst showed positive staining on day 5 morning (Fig. 4Ab), numerous cells in the similar region showed intense staining on day 5 afternoon (Fig. 4Ad). These results suggest that p21 is involved in directing cyclin D3 functions in stromal cell proliferation and differentiation during the onset of decidualization. With the establishment of the PDZ on days 6 and 7, the non-proliferating cells in this region showed virtual absence of both cyclin D3 and p21 (Fig. 4Ae–h). In contrast, cells next to the PDZ that form the SDZ showed intense staining for cyclin D3 and p21 (Fig. 4Ae–h). The SDZ is comprised of both proliferating and differentiating cells with polyploidy. We observed that numerous large mono- and bi-nucleated cells expressed cyclin D3 with p21 in a same region of the decidual bed (Fig. 4Ai,j), suggesting that an interaction between these molecules is important for polyploidization. On day 8, the expression of cyclin D3 and p21 was again noted with similar distribution in cells at the mesometrial pole and in some decidual cells at the antimesometrial pole (data not shown). The co-localization of cyclin D3 with p21 in the SDZ was further confirmed by double immunofluorescence technique using antibodies tagged with Cy3 for cyclin D3 or FITC for p21 (Fig. 4B). The results clearly demonstrate that the co-expression of both cyclin D3 and p21 is associated with large mono- or bi-nucleated cells in the antimesometrial decidual bed. This observation led us to examine whether cdk4 and cdk6 are present in decidual cells to interact with cyclin D3 and p21.

Fig. 4.

(A) Immunohistochemical staining of cyclin D3 and p21 in the mouse uterus during decidualization. Mouse uteri collected during pregnancy on D5 at 09:00 and 18:00 h, and D6 and D7 at 09:00 h were analyzed. Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded adjacent sections (6 μm) collected from an implantation site were mounted onto poly-L-lysine-coated slides. After deparaffinization and hydration, sections were incubated with primary antibody either for cyclin D3 or p21 in PBS for 17 h at 4°C. The photomicrographs of representative uterine sections are shown with bars, 100 μm. Red nuclear staining indicates the localization of immunoreactive proteins. Mono- and bi-nucleated cells are indicated by arrowheads and arrows, respectively. No immunostaining was noted when similar sections were incubated with the primary antibody pre-neutralized with excess antigen (data not shown). M, mesometrial pole; AM, antimesometrial pole; em, embryo; le, luminal epithelium; ds, decidualizing stroma,; PDZ, primary decidual zone; SDZ, secondary decidual zone. (B) Dual immunofluorescence study for cyclin D3 and p21 on day 6 of pregnancy at the antimesometrial pole of the implantation site. Uterine sections were stained with Cy3 (red) or FITC (green) tagged secondary antibody for cyclin D3 and p21, respectively. A superimposed picture at the middle, showing cells highlighted with yellow color, actually represents the expression of both cyclin D3 and p21. Arrows or arrowhead represent mono- or bi-nucleated polyploid cells, respectively.

Our immunohistochemical analysis showed that nuclear localization of cdk4 was primarily restricted to cells in the mesometrial decidual bed on day 6 (Fig. 5a) as compared to the cells in the antimesometrial decidual bed (Fig. 5c). In contrast, nuclear localization of cdk6 was primarily noted in decidual cells at the antimesometrial pole (Fig. 5d), but not in cells at the mesometrial pole (Fig. 5b). In addition, numerous large mono- and bi-nucleated cells were positive for cdk6 in the SDZ (Fig. 5d). Overall, these results suggest that cyclin D3 together with p21 and cdk6 participates in polyploidization and cdk4 plays minimal role in this process. Functional association of cyclin D3 and p21 with cdk6 or cdk4 was next examined to confirm this possibility.

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of cdk4 and cdk6 in the mouse uterus during decidualization on D6 of pregnancy. The photomicrographs of representative uterine sections are shown for cdk4 (a,c) and cdk6 (b,d) in locations of mesometrial (a,b) and antimesometrial (c,d) regions of the decidual bed at 100 ×. Red staining indicates the localization of immunoreactive proteins. No immunostaining was noted when similar sections were incubated with the primary antibody pre-neutralized with excess antigen (data not shown). M, mesometrial pole; AM, antimesometrial pole; em, embryo; PDZ, primary decidual zone; SDZ, secondary decidual zone.

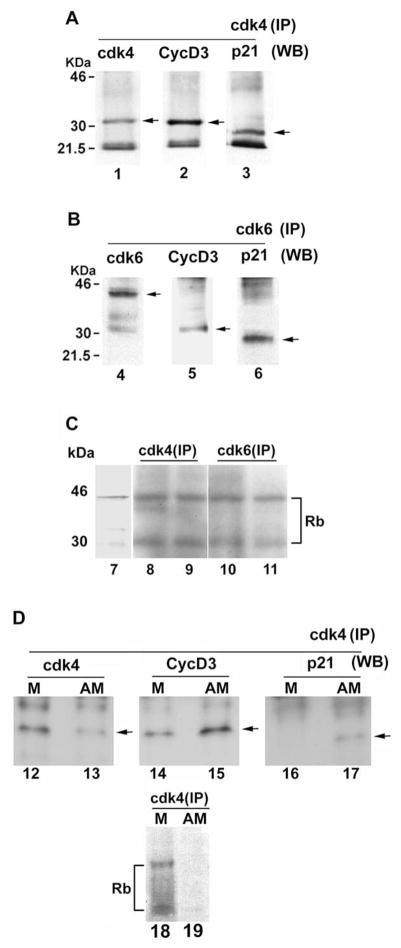

2.3. Cyclin D3 and p21 are functionally associated with cdk4 and cdk6 during decidualization

To examine whether cyclin D3 and p21 forms a functional ternary complex with cdk4 or cdk6, we performed co-immunoprecipitation analysis using day 6 decidual tissues with specific antibodies to cdk4 or cdk6. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed for the presence of respective cell cycle molecules by Western blotting (Figs. 6A,B). The functional activity of the associated complex in the immunoprecipitate was assayed for kinase activities of cdk4 or cdk6 using Rb as a phosphorylated substrate (Fig. 6C). Our results demonstrate that cyclin D3 and p21 associate with cdk4 or cdk6 at the site of implantation on day 6 of pregnancy, and these ternary complexes are functionally active in phosphorylating Rb in kinase assays. Given the expression pattern of cdk4, cyclin D3 and p21 on day 6 of pregnancy, it is anticipated that both the active and inactive forms of cdk4 should exist in the uterine decidual bed around this time of pregnancy. Thus, we analyzed the kinase activity and the association of the co-immunocomplex by cdk4 antibody in separated antimesometrial and mesometrial deciduomal tissues on day 7 after induction of decidualization by intraluminal oil infusion on day 4 of pseudopregnancy. As shown in Fig. 6D, the kinase activity was undetectable in antimesometrial tissue extracts by cdk4 antibody, although the association of p21 with cyclin D3 and cdk4 was clearly evident. In contrast, similar experiments with the mesometrial extracts showed kinase activity with undetectable association of p21 with cdk4.

Fig. 6.

Analyses of the associated complex and the functional activity formed by cdk4 or cdk6 together with cyclin D3 and p21. (A) Complex with cdk4: uterine implantation sites on D6 of pregnancy were extracted and subjected to immunoprecipitation using cdk4 polyclonal antibody. Immunoprecipitates were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and then detected by Western blotting using antibodies for cdk4, cyclin D3 or p21. The bands specific to cdk4, cyclin D3 and p21 are indicated by arrows in lanes 1, 2 and 3, respectively. (B) Complex with cdk6: uterine implantation sites on D6 of pregnancy were extracted, immunoprecipitated by cdk6 polyclonal antibody, separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using primary antibodies for cdk6, cyclin D3 and p21. The bands specific to cdk6, cyclin D3 and p21 are indicated by arrows in lanes 4, 5 and 6, respectively. (C) Kinase activities in cdk4- or cdk6-associated complex at the site of implantation on day 6 of pregnancy: Immunoprecipitates as obtained from two independent samples of tissue extracts of D6 implantation sites using cdk4 (lanes 8 and 9) or cdk6 (lanes 10 and 11) antibodies were subjected to kinase assay using [γ-32P]ATP and a protein substrate (mouse recombinant Rb fusion protein) as described in Materials and Methods. The phosphorylated proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, dried and subjected to autoradiography. The recombinant Rb was run on the same gel in parallel and visualized by Coomasie blue staining (lane 7). Two phosphorylated protein bands corresponding to Rb were detected as 45 and 30 kDa. (D) Analyses of cdk4-associated immunocomplex and its kinase activity in the separated antimesometrial (AM) and mesometrial (M) deciduomal tissues obtained on day 7 after induction of artificial decidualization on day 4 of pseudopregnancy. The bands specific to cdk4, cyclin D3 and p21 are indicated by arrows (lanes 12–17). Lanes 18 and 19 are shown for cdk4-associated kinase activity in the mesometrial (M) and antimesometrial (AM) deciduomal tissues, respectively.

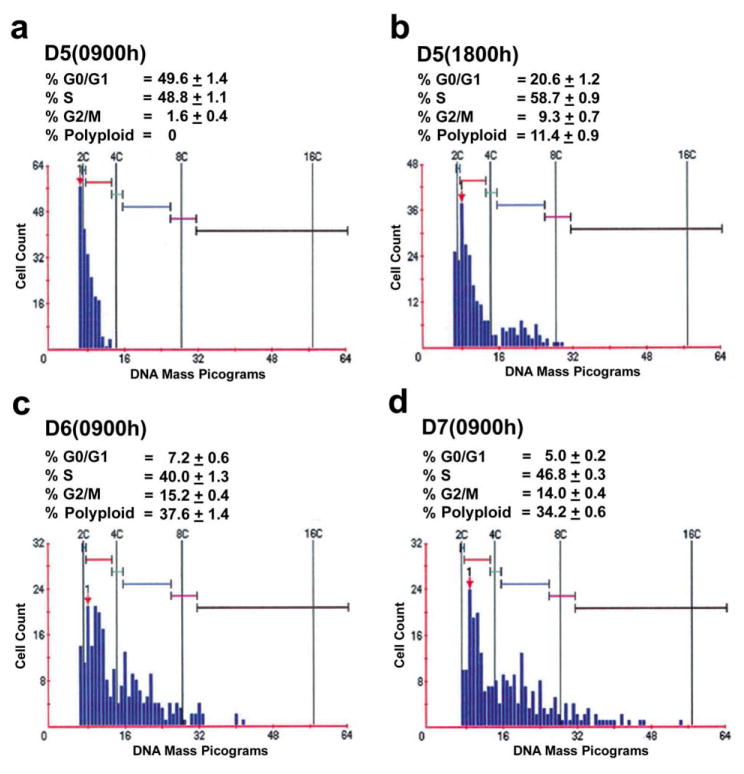

2.4. Expression of cyclin D3 and p21 in polyploid decidual cells correlates with the arrest of the G2/M phase and increased polyploidy

To investigate further the involvement of cyclin D3 and p21 in antimesometrial decidual cells with the formation of polyploidy, we examined whether there is a relationship between the localization of cell cycle regulators (cyclin D3 and p21) and the DNA content in decidualizing stroma on serial sections during days 5–7 of pregnancy as assessed by immunohistochemical and cytomorphometric analyses. The cell nuclei were randomly analyzed for quantitative measurement of DNA content from an area in the antimesometrial pole where cyclin D3 and/or p21 were positive for each respective day of pregnancy as shown by immunohistochemistry in Fig. 4A. A significantly higher percentage of cells (≈ 49%) equally distributed in G0/G1 and S phases in uterine sections on day 5 morning (09:00 h), without showing any detectable polyploidy (>4C) (Fig. 7a). However, with the progression of decidualization from day 5 afternoon (18:00 h) through day 7 (09:00 h), number of cells in the G0/G1 phase significantly decreased (P < 0.001), while cells in the G2/M phase showed a significant (P < 0.001) increase (Fig. 7b–d). Furthermore, there was a steady increase in the number of cells with ployploidy. These results show that an increasing number of cells with cyclin D3 and p21 undergo endocycle during these periods. At the peak time of polyploidy on day 6 (09:00 h), a significant number (≈ 6.7 ± 0.3%) of cells had a DNA content higher than 8C; this is consistent with a previous report (Ansell et al., 1974).

Fig. 7.

DNA content and the cell cycle distribution of uterine antimesometial stromal cells at the implantation sites. Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded sections (6 μm) of implantation sites on D5–D7 of pregnancy at indicated times were subjected to Feulgen staining and analyzed for measurements of DNA content by CAS-200 imaging system as described in Materials and Methods. In order to demarcate the location of the antimesometial decidual bed, adjacent sections were examined in parallel by immuonohistochemical staining for cyclin D3 and p21 as shown in Fig. 3A. On each day of pregnancy, four different implantation sites on duplicate adjacent sections were analyzed. In average, 500–600 nuclei were analyzed for each implantation site. The DNA content for diploid nuclei was optimized with non-differentiated stromal cells on day 4 of pregnancy. The percent of cell cycle distribution was calculated as mean ± SEM. The colored bars represent several multiples of normal haploid DNA content (C).

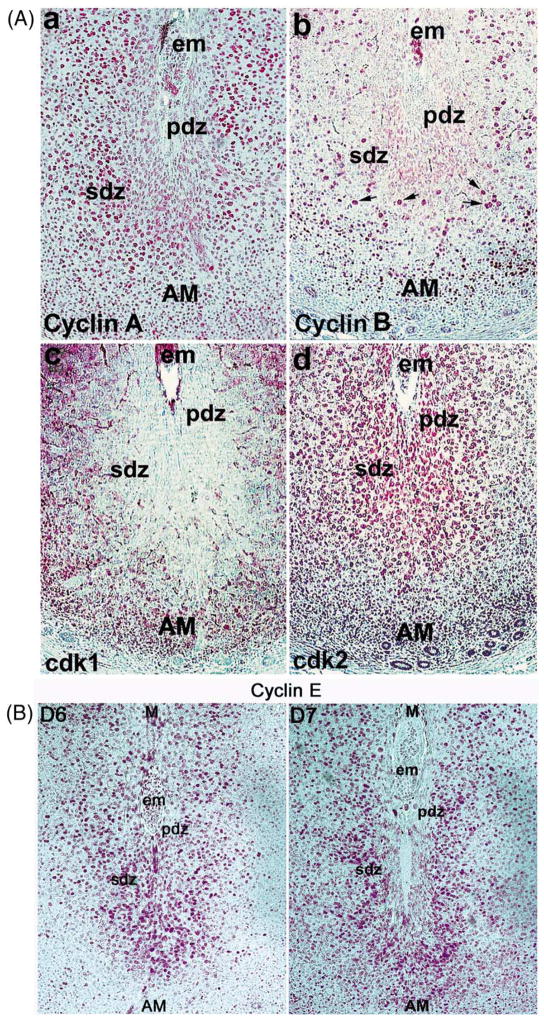

2.5. Decidual cell polyploidy is associated with the downregulation of the G2 phase cell cycle regulators

To further understand the mechanism of decidual cell cycle polyploidy, we examined the expression status of S-G2-M phase cell regulators in the uterus during the peak time of polyploidy on day 6 of pregnancy. In situ hybridization demonstrated heightened expression of cyclin A mRNA in both the antimesometial and mesometrial decidual cells on day 6 of pregnancy, while that of cyclin B was significantly low in these cells (data not shown). Immunohistochemical analysis also showed that while only a small number of cells with large nuclei showed positive staining for cyclin B (Fig. 8Ab, arrows), a large number of polyploid cells were positive for cyclin A (Fig. 8Aa). Furthermore, the localization of cdk1 (Fig. 8Ac) and cdk2 (Fig. 8Ad) followed the pattern of cyclin B and cyclin A, respectively. These results suggest that downregulation of cyclin B and cdk1 is associated with the stromal cell polyploidy. It has been shown that cyclin E is an important regulator for the transition from G1 to S in both the mitotic cycle and the endocycle pathways (Edgar and Orr-Weaver, 2001). Indeed, we observed that cyclin E is expressed in the polyploid stromal cells in the SDZ on days 6 and 7 of pregnancy (Fig. 8B), suggesting its involvement in the endocycle during the progression of stromal cell polyploidization.

Fig. 8.

(A) Expression of cyclin A, cyclin B, cdk1 and cdk2 in the uterus on D6 of pregnancy. (B Expression of cyclin E on days 6 and 7 of pregnancy. Immunohistochemical staining on formalin-fixed paraffin sections (6 μm) of implantation sites is shown at 100 ×. The photomicrographs of representative uterine sections are shown mostly for the antimesometrial region of the decidual bed. Red staining indicates the localization of immunoreactive proteins. No immunostaining was noted when similar sections were incubated with the primary antibody pre-neutralized with excess antigen (data not shown). Arrows indicate polyploid cells. M, mesometrial pole; AM, antimesometrial pole; em, embryo; PDZ, primary decidual zone; SDZ, secondary decidual zone.

3. Discussion

3.1. Expression patterns of cyclin D3/P21/cdk4 or cdk6 suggest roles in directing proliferation and differentiation of decidualizing stromal cell

Although cell cycle activity is implicated in the control of stromal cell decidualization and polyploidy in rodents (Sachs and Shelesnyak, 1955; Ansell et al., 1974; Das et al., 1999), distinctive and overlapping interactions of cell regulatory molecules in these events remain poorly understood. The highlight of the present investigation is that among the D-type cyclins examined cyclin D3 appears to play an important role in stromal cell proliferation, differentiation and polyploidy in a stage-specific manner with the progression of implantation. For example, heightened expression of cyclin D3 in association with cdk4 correlates with intense stromal cell proliferation surrounding the implanting blastocyst on day 5 morning (Figs. 1e,i and 4Aa). In contrast, downregulation of cyclin D3 and cdk4 in cells close to the implanting embryo on day 5 afternoon is correlated with the cessation of proliferation and initiation of the PDZ formation (Figs. 1f,j and 4Ac). Disappearance of these regulators from cells in the fully established PDZ on day 6 perhaps heralds the death of these cells, which indeed occurs shortly after the formation of the PDZ. On the other hand, the persistent expression of cyclin D3 and cdk4 in the stroma outside the PDZ in the afternoon (18:00 h) of day 5 again correlates with cell proliferation in this region. The presence of very low levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin D2 in the decidualizing stroma with no cell-specific localization raises questions regarding their roles in this process (Fig. 1a–d). While this is consistent with normal fertility in cyclin D1 null mice (Fantl et al., 1995; Sicinski et al., 1995), it is not yet known whether cyclin D2 null females have defective implantation and/or decidualization, although female infertility in these mice resulting from abnormal ovarian functions has been established (Sicinski et al., 1996; Robker and Richards, 1998).

Stromal cell transformation to decidual cells is a tightly controlled event and is likely to involve a balance between the expression of cyclins and CKIs (Sherr and Roberts, 1999). Thus, a reciprocal regulation by these two classes of molecules could be an important mechanism of controlling stromal cell decidualization. Indeed, we here provide evidence that there is disparate and overlapping expression of p21 with cyclin D3/cdk4 at the site of implantation (Figs. 1–5). The luminal epithelium at the site of the blastocyst is destined to undergo apoptosis soon after the initiation of implantation. Thus, the accumulation of p21 in the luminal epithelium in the absence of cyclin D3 on day 5 morning suggests its role in inhibiting proliferation and accelerating death of these cells (Fig. 4Aab). The expression of p21 in stromal cells immediately surrounding the implanting blastocyst in the afternoon of day 5 with downregulated cyclin D3/cdk4 suggests that this population of cells is undergoing differentiation to form the PDZ (Figs. 1f,j and 4Ac,d). Furthermore, downregulation of cdk4 with persistent expression of p21 in the SDZ on day 6 of pregnancy is again consistent with the differentiation of the cells in this zone (Figs. 4Af and 5c). In contrast, co-expression of cyclin D3 with p21 in the SDZ (Fig. 4Ae–f,B) and their distribution in similar regions of the dicidual bed with cdk6 (Figs. 1o and 5d) from day 6 onward suggests that an interaction between these molecules is involved in polyploidization of the decidualizing stromal cells in the SDZ. There is evidence that the expression of p21 during development strongly correlates with terminally differentiated cells (Parker et al., 1995). Our data on p21 expression in the SDZ also suggest that this inhibitor promotes terminal differentiation of stromal cells in a region specific manner, since these cells eventually undergo apoptosis. Our preliminary results show that p53 is displayed in decidual cells similar to that of p21 (unpublished results). There is evidence that p53 plays a role in apoptosis induced by DNA damage, presumably via p21 (Kagawa et al., 1997). Thus, the heightened expression of p21 together with p53 could be involved in apoptotic death of these cells. Although embryo development and implantation are apparently normal in p21 null mice (Deng et al., 1995), it is possible that the other functionally similar inhibitory molecules compensate for p21 deficiency. As shown here, the overlapping and distinctive expression patterns of p27 could suggest its function similar to or different from those of p21 (Fig. 2Bb,c vs. e,f).

The normal functioning of D-type cyclins is dependent on kinase activities of cdk4 and/or cdk6. The expression of cdk4 and cdk6 in an opposite fashion in the decidual bed on day 6 of pregnancy suggests that they have different regulatory roles in cell cycle with respect to the development of mesometrial and antimesometrial decidual bed (Figs. 1k,o and 5a–d). This suggestion is consistent with our functional analysis of the co-immunoprecipitated complex by antibodies to cdk4 or cdk6. Cdk4-dependent kinase activity was predominant at the mesometrial pole, while its activity was undetectable in the antimesometial pole with the development of SDZ (Fig. 6D, lanes 18,19). In contrast, cdk6 was expressed exclusively at the antimesometiral pole with detectable kinase activity at the implantation site (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that cdk6 is the primary regulator for the development of antimesometial decidua. Recent studies have shown that cdk4 null mice are infertile (Rane et al., 1999; Tsutsui et al., 1999). Smaller ovarian sizes with defective granulosa cell functions are characteristic phenotypes of cdk4 null mice. In addition, recent findings from Kiyokawa’s laboratory (University of Illinois, Chicago) suggest that these females show decidualization defects (personal communication).

3.2. Cell cycle regulation in directing stromal cell polyploidy

For normal cell division, cells must receive a complete copy of their genome each time. To ensure genomic stability, the S phase is tightly regulated so that replication of the chromosomes is initiated only once in each cell cycle. It has recently been speculated that the loss of this regulation results in polyploidy that allows cells to undergo continuous endocycle without cell division (Edgar and Orr-Weaver, 2001). Alterations in the status of cell cycle molecules have been reported with the development of polyploidy in several cell lineages (Kiess et al., 1995; Kikuchi et al., 1997; Zimmet et al., 1997; MacAuley et al., 1998). For example, there is evidence that overexpression of cyclin D3 leads to polyploidization of megakaryocytes with reduced kinase activity of cyclin B1-dependent cdk1 (Zimmet et al., 1997). Similarly, p21 is also implicated in polyploidization associated with megakaryocytic differentiation (Kikuchi et al., 1997). Furthermore, cyclin D3 expression in various myoblast cell lines correlates with their terminal differentiation into multinucleated quiescent myotubes (Kiess et al., 1995). A classic example of endoreduplication during pregnancy in rodents is the differentiation of trophoblast giant cells that is accompanied by a distinct switch of cyclin D3 to cyclin D1 expression with concomitant downregulation of cyclin B associated kinase activity (MacAuley et al., 1998).

Uterine stromal cell polyploidization is also thought to involve atypical cell cycle regulation (Sachs and Shelesnyak, 1955; Ansell et al., 1974). Our observation of heightened expression of cyclin D3 and p21 in conjunction with cdk6, but not cdk4, in polyploid stromal cells or preceding polyploidy suggests that an associated complex of cyclin D3/cdk6/p21 is involved in polyploidization of uterine stromal cells. Using serial sections of the implantation sites on day 6, we observed the absence of cyclin B and cdk1, regulators for G2-M progression, in polyploid cells, suggesting that these cells are unable to progress through the normal cell cycle (Fig. 8Ab,c). This is consistent with our findings of cytomorphometric analysis on adjacent sections of the uterus showing continued DNA synthesis in cells in the antimesometrial decidual bed with an arrest in the G2 phase, resulting in polyploidy (Fig. 7). However, it should be noted that about 35% of cells normally undergo polyploidy in the SDZ on days 6 and 7 of pregnancy (Fig. 7c,d), while the characteristics of remaining cells within the same region remain unresolved from our current study. Furthermore, because of the limitation of our data analysis, it remains unclear whether all of the cells that are positive for cyclin D3/cdk6/p21 are indeed polyploid. Although the p21 family of proteins normally interferes with cyclins (D, E and A) dependent activities, recent evidence suggests that they can also act as positive regulators of D-type cyclins (reviewed in Sherr and Roberts, 1999). Thus, it is possible that cyclin D3 together with p21 acts positively for the entry of cells from G1 to S phase. This suggestion is consistent with our cytomorphometric analysis showing that cyclin D3/p21 positive cells are not arrested at the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 7). It is also possible that cyclin D3/p21/cdk6 complex in polyploid cells is important for the progression through the G phase during the first endocycle, while the expression of cyclin E is required for continuation of the endocycle. Indeed, our results show that cyclin E is expressed in polyploid cells on days 6 and 7 of pregnancy (Fig. 8B). Rb is considered an important factor in cellular response to p21, particularly in the context of cellular regulation of DNA replication (Niculescu et al., 1998). Our observation of the presence of p107 and p130 (Fig. 2A), but not Rb, in decidual and polyploid cells suggests that these cells do not use Rb for execution of D-type cyclin functions, rather they use p107 and p130 for such functions.

3.3. A model for stromal cell proliferation, differentiation and polyploidy associated with decidualization

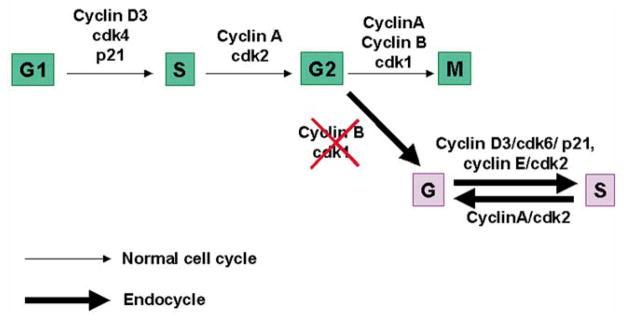

Currently very limited information is available regarding the distinct or overlapping roles of various cell cycle molecules during the onset of stromal cell decidualization. Using multiple approaches, we propose a model (Fig. 9) to describe cell cycle regulation of stromal cell proliferation, differentiation and polyploidy associated with decidualization. The coordinate expression of cdk4 and cyclin D3 at the site of embryo following the onset of implantation on day 5 of pregnancy suggests that these regulators play roles in proliferation of stromal cells undergoing decidualization. However, the expression of p21 with concomitant down-regulation of cyclin D3 and cdk4 in the PDZ at the implantation site in the afternoon of day 5 supports the view that cell proliferation activity of cdk4/cyclin D3 ceases with the development of the PDZ. Furthermore, the expression of cdk4 and cyclin D3 in the afternoon of day 5 in decidualizing stroma outside the PDZ is again consistent with their role in proliferation of the stroma at the SDZ. In contrast, down-regulation of cdk4 in the SDZ with persistent expression of p21 on day 6 (09:00 h) of pregnancy perhaps directs differentiation of stromal cells in this zone. Furthermore, at this time of pregnancy, a switch from cdk4 to cdk6 with continued expression of cyclin D3 and p21 in cells of the SDZ is consistent with the progression of these cells through the G-phase for the onset of endocycle. This is further supported by the observation of coordinated expression of cyclin E and cyclin A and cdk2 in the polyploid cells for successful progression in G and S phases of the endocycle pathway. Although the definitive cause of stromal cell polyploidy still remains unknown, the down-regulation of cyclin B and cdk1 in polyploid cells might suggest a role to the onset of polyploidy in the stroma. Overall, our study provides a comprehensive analysis for the first time regarding the interplay of the cell cycle molecules in a very dynamic system like the pregnant uterus during stromal cell decidualization.

Fig. 9.

A potential model for stromal cell transition from the mitotic to the endocycle pathway for polyploidization. This model describes presumed functional association of the G1 phase cell regulators (cyclin D3, p21, cdk4, cdk6, cyclin E and cdk2) and that of the S-G2-M phases (cyclin A, cyclin B, cdk1 and cdk2) with respect to cell cycle events associated with the switch from mitotic cycle to endocycle during stromal cell decidualization. The absence of cyclin B and cdk1 is speculated to participate with the onset of first endocycle.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals and tissue preparation

CD-1 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC) were housed in the animal care facility at the University of Kansas Medical Center in accordance with NIH standards for the care and use of experimental animals. Adult females were mated with fertile males of the same strain to induce pregnancy (day 1, vaginal plug). On days 5 and 6, implantation sites were identified by monitoring the localized uterine vascular permeability at the site of the blastocyst after intravenous injection of Chicago Blue B dye solution (1% in saline) (Psychoyos, 1973). On days 7 and 8, implantation sites are distinct and their identification does not require any special manipulation. For protein analyses using immunoprecipitation and/or Western blotting, sites for implantation (IS) and interimplantation (Int-IS) regions were collected on day 6 of pregnancy.

4.2. Hybridization probes

Mouse cDNA clones for the full-length coding region of cyclins D1 and D2 in pBluescript vector were obtained from Charles Sherr (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Memphis, Tennessee). Cyclin D3 clone has previously been described (Das et al., 1999). RT-PCR derived mouse specific cDNA clones for cdk4, cdk6, cyclin A, cyclin B, p21, p27 and Rb were generated from day 6 uterine RNA samples. The cDNA fragments for cdk4 (nts 207–610, acc# L01640), cdk6 (nts 363–738, acc# X66365), cyclin A (nts 497–989, acc# Z26580), cyclin B (nts 351–844, acc# X58708), p21 (nts 55–453, acc# U24173), p27 (nts 139–513, acc# U09968) and Rb (nts 791–1186, acc# M26391) were subcloned in pCRIITOPO vector. The authenticity for each of these clones was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. The clone used for mouse ribosomal protein L7 (rpL7) has previously been described (Das et al., 1999). For in situ hybridization, sense and antisense 35S-labeled cRNA probes were generated. The probes had specific activities of 2 × 109 dpm/μg.

4.3. In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Das et al., 1999). In brief, frozen sections (11 μm) were mounted onto poly-L-lysine coated slides and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at 4°C. Sections were prehybridized followed by hybridization with 35S-labeled antisense or sense cRNA probes for 4 h at 45°C. After hybridization and washing, the sections were incubated with RNase-A (20 μg/ml) at 37°C for 20 min. RNase-A resistant hybrids were detected by autoradiography using Kodak NTB-2 liquid emulsion (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). The slides were post-stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sectioned hybridized with the sense probes served as negative controls.

4.4. Antibodies

The affinity purified rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against peptides corresponding to various cell cycle regulatory proteins, such as cyclins D1 (Cat# sc-717), D2 (Cat# sc593), D3 (Cat# sc-182), A (Cat# sc-596); p53 (Cat# sc-6243), pRb (Cat# sc-4112), cdk1/cdc2 (Cat# sc-54), cdk2 (Cat# sc-163), cdk4 (Cat# sc-260) and cdk6 (Cat# sc-177) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit polyclonal antibody to p21 (Cat# PC55), generated against a recombinant protein consisting amino acids 15–61 of mouse p21, was purchased from Oncogene Research Products (Cambridge, MA). A monoclonal antibody for p27, obtained from mouse ascites by epitope-affinity chromatography using full-length human recombinant p27 protein, was obtained from Zymed Laboratories Inc. (San Francisco, CA). All of these antibodies are mouse specific and show no cross-reactivity with related proteins. These antibodies were used for immunostaining, immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

4.5. Immunohistochemical staining

The method followed the protocol as previously described by us (Tan et al., 1999). In brief, formalin-fixed paraffin embedded sections (6 μm) were deparaffinized, hydrated and irradiated in the microwave oven for the antigen retrieval. Nonspecific reaction was blocked by incubation in 10% non-immune serum. Sections were incubated with primary antibody at 4°C for 17 h, followed by incubation in secondary antibody for 10 min. Staining reaction was performed utilizing a Zymed-Histostain-SP kit (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA). Red deposits indicted the sites of positive immunostaining. Immunoneutralization was performed by incubating sections with preneutralized primary antibody with 250 fold molar excess of peptide antigen.

4.6. Western blot analysis

The method followed the protocol as previously described by us (Tan et al., 1999). In brief, proteins were extracted by homogenization with Polytron homogenizer in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl and proteinase inhibitors (1 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 μg/ml aprotinin and 1 μg/ml leupeptin). The homogenates were centrifuged and the supernatants (50 μg protein) were boiled for 5 min in 1 × SDS sample buffer. After a brief centrifugation, samples were run on 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing condition and electrophoretically transferred onto Immobilon membranes. The membranes were incubated with 5% carnation milk in TBST buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 15 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween-20) for overnight at 4°C to block nonspecific binding and then incubated with primary antibody containing 5% milk in TBST for overnight at 4°C or 2 h at room temperature. For control experiments, primary antibodies pre-neutralized with 250-fold molar excess of corresponding antigenic peptide were used (data not shown). Membranes were then washed and incubated with goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG coupled to horseradish peroxidase (1:5000) in 5% milk for 1 h. The bands were detected by ECL kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

4.7. Analysis of immunocomplex by Western blotting and kinase assay

The uterine tissue extracts as obtained for Western blotting were immunoprecipitated using a protocol as previously described by us (Halder et al., 2000). In brief, the protein extracts (250 μg) was incubated in a buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, 10 glycerol, 1 mM DTT and 20 μg/ml PMSF) with 2 μg of primary antibody for cdk4 or cdk6 conjugated with protein A agarose beads for 90 min at 4°C with a gentle agitation. The beads were washed 3 times with 1 ml HNTG buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol) and the bound proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in 1 × SDS sample buffer for 5 min. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min, the supernatants were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto Immobilon membrane and Western blotted as described above.

The protocol for kinase assay was essentially same as described (Matsushime et al., 1994). The uterine tissue protein (250 μg) immunoprecipitated on protein A agarose beads were washed thoroughly three times with 1 ml each of HNTG and two times with 1 ml each of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM DTT. The washed beads were suspended in 30 μl kinase buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM Naorthovanadate, 1 mM NaF) containing 1 μg substrate Rb fusion protein, 769 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 20 μM ATP, 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. After incubation for 30 min at 30°C with occasional mixing, the samples were boiled with 1 × SDS sample buffer and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylated proteins were visualized by autoradiography of the dried gel.

4.8. Cytomorphometric image analysis of nuclear DNA content (ploidy levels) and distribution of antimesometrial decidual cells in the cell cycle

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded embryo implantation sites on days 5–7 of pregnancy were sectioned (6 μm) as cross-sections. Adjacent sections from a single implantation site were mounted onto various poly-L-lysine coated slides. Sections were then deparaffinized, hydrated and washed in PBS, and they were divided into two groups. One group was used for Feulgen staining for cytomorphometic imaging (Klisch et al., 1999), while the other group was used for immunostaining of cyclin D3 and p21 in parallel to demarcate a location within the decidual bed. Feulgen staining was performed by hydrolysis in 5 N HCl at room temperature for 30 min, followed by incubation in Schiffs reagent for 2 h in the dark. After washing twice in freshly prepared sulphonic water (0.5% (w/v) Na2S2O5 in 0.05 N HCl) and once in deionized water, the slides were then dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol, rinsed in xylene and covered with coverslips. The Feulgen DNA staining method provides a reliable stoichiometric staining of nuclear DNA. All images from Feulgen stained sections were captured and analyzed using a CAS-200 Image Analysis System (BACUS Laboratories Inc., Lombard, IL 60148). The CAS-200 imaging system utilizes a camera and frame grabber that generates rectangular pixels (0.19 μm2) with a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels. The computer based (a software program using quantitative DNA analysis version 3.0) image analysis system uses the summation of the optical density of each Feulgen-stained nucleus to calculate the amount of DNA content based on the Beer–Lambert law. The histogram demonstrating the frequency distribution of measured nuclear DNA content was used to determine the presence of polyploidy and the cell cycle distribution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants (ES-07814 and HD-37830 to S.K. Das, and HD-12304, HD-29968 and HD-33994 to S.K. Dey) and Mellon Foundation. Center grants in Reproductive Biology (HD-33994) and Mental Retardation (HD-02528) at the University of Kansas Medical Center provided access to various core facilities.

References

- Ansell JD, Barlow PW, McLaren A. Binucleate and polyploid cells in the decidua of the mouse. J Embryol Experi Morphol. 1974;31:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger AM, Sudahl S, Bamberger CM, Schulte HM, Lo ning T. Expression patterns of the cell-cycle inhibitor p27 and the cell cycle promoter cyclin E in the human placenta throughout gestation: Implications for the control of proliferation. Placenta. 1999;20:401–406. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das SK, Lim H, Paria BC, Dey SK. Cyclin D3 in the mouse uterus is associated with the decidualization process during early pregnancy. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999;22:91–101. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0220091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Lader P. Mice lacking p21Cip1/Waf1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey SK. Implantation. In: Adashi EY, Rock JA, Rosenwaks Z, editors. Reproductive Endocrinology, Surgery and Technology. Lippincott-Raven Publishers; New York: 1996. pp. 421–434. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, Orr-Weaver TL. Endoreplication cell cycles: more or less. Cell. 2001;105:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantl V, Stamp G, Andrews A, Rosewell I, Dickson C. Mice lacking cyclin D1 are small and show defects in eye and mammary gland development. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2364–2372. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geum D, Sun W, Paik SK, Lee CC, Kim K. Estrogen-induced cyclin D1 and D3 gene expressions during mouse uterine cell proliferation in vivo: differential induction mechanism of cyclin D1 and D3. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46:450–458. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199704)46:4<450::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder JB, Zhao X, Sokar S, Paria BC, Klagsbrun M, Das SK, Dey SK. Differential expression of VEGF isoforms and VEGF164-specific receptor neuropilin-1 in the mouse uterus suggest a role for VEGF164 in vascular permeability and angiogenesis during implantation. Genesis. 2000;26:213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa S, Fujiwara T, Hizuta A, Yasuda T, Zhang WW, Roth JA, Tanaka N. P53 expression overcomes p21WAF1/CIP1-mediated G1 arrest and induces apoptosis in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 1997;15:1903–1909. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiess M, Gill RM, Hamel PA. Expression of the positive regulator of cell cycle progression, cyclin D3, is induced during differentiation of myoblasts into quiescent myotubes. Oncogene. 1995;10:159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klisch K, Hecht W, Pfarrer C, Schuler G, Hoffmann B, Leiser R. DNA content and ploidy level of bovine placentomal trophoblast giant cells. Placenta. 1999;20:451–458. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi J, Furukawa Y, Iwase S, Terui Y, Nakamura M, Kitagawa S, Kitagawa M, Komatsu N, Miura Y. Polyploidization and functional maturation are two distinct processes during megakaryocytic differentiation: involvement of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in polyploidization. Blood. 1997;89:3980–3990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAuley A, Cross JC, Werb Z. Reprogramming the cell cycle for endoreduplication in rodent trophoblast cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:795–807. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushime H, Quelle DE, Shurtleff SA, Shibuya M, Sherr CJ, Kato JY. D-type cyclin dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2066–2076. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton BC. Effect of progesterone on DNA, RNA and protein synthesis of deciduoma cell fractions separated by velocity sedimentation. Biol Reprod. 1979;21:667–672. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod21.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu AB, Chen X, Smeets M, Hengst L, Prives C, Reed SI. Effects of p21(Cip1/Waf1) at both the G1/S and the G2/M cell cycle transitions: pRb is a critical determinant in blocking DNA replication and in preventing endoreduplication. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:629–643. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SB, Eichele G, Zhang P, Rawls A, Sands AT, Bradley A, Olson EN, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. p53-independent expression of p21Cip1 in muscle and other terminally differentiating cells. Science. 1995;267:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7863329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prall OWJ, Sarcevic B, Musgrove EA, Watts CKW, Sutherland RL. Estrogen-induced activation of cdk4 and cdk2 during G1-S phase progression is accompanied by increased cyclin D1 expression and decreased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor association with cyclin E-cdk2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10882–10894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychoyos A. Endocrine control of egg implantation. In: Greep RO, Astwood EG, Geiger SR, editors. Handbook of Physiology. American Physiological Society; Washington DC: 1973. pp. 187–215. [Google Scholar]

- Rane SG, Dubus P, Mettus RV, Galbreath EJ, Boden G, Reddy EP, Barbacid M. Loss of Cdk4 expression causes insulin-deficient diabetes and Cdk4 activation results in beta-islet cell hyperplasia. Nat Genet. 1999;22:44–52. doi: 10.1038/8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnitzky DM, Gossen H, Bujard H, Reed SI. Acceleration of the G1/S phase transition by expression of cyclins D1 and E with an inducible system. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1669–1679. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley DJ, Lee EYHP, Lee WH. The retinoblastoma protein more than a tumor suppressor. Annu Rev Cell Bio. 1994;10:1–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JM. Evolving ideas about cyclins. Cell. 1999;98:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robker RL, Richards JS. Hormone-induced proliferation and differentiation of granulosa cells: A coordinated balance of the cell cycle regulators cyclin D2 and p27kip1. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:924–940. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.7.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs L, Shelesnyak MC. The development and suppression of polyploidy in the developing and suppressed deciduoma in the rat. J Endocrinol. 1955;12:146–151. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0120146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulations of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa T, Nikaido T, Nakayama K, Lu X, Fujii S. Involvement of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 in growth inhibition of endometrium in the secretory phase and of hyperplastic endometrium treated with progesterone. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:899–905. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.9.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicinski P, Donaher JL, Parker SB, Li T, Fazell A, Gardner H, Haslam SZ, Bronson RT, Elledge SJ, Weinberg RA. Cyclin D1 provides a link between development and oncogenesis in the retina and breast. Cell. 1995;82:621–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicinski P, Donaher JL, Geng Y, Parker SB, Gardner H, Park MY, Robker RL, Richards JS, McGinnis LK, Biggers JD, Eppig JJ, Bronson RT, Elledge SJ, Weinberg RA. Cyclin D2 is an FSH-responsive gene involved in gonadal cell proliferation and oncogenesis. Nature. 1996;384:470–474. doi: 10.1038/384470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Paria BC, Dey SK, Das SK. Differential uterine expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors correlates with uterine preparation for implantation and decidualization in the mouse. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5310–5321. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui T, Hesabi B, Moons DS, Pandolfi PP, Hansel KS, Koff A, Kiyokawa H. Targeted disruption of CDK4 delays cell cycle entry with enhanced p27(Kip1) activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7011–7019. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmet JM, Ladd D, Jackson CW, Stenberg PE, Ravid K. The role for cyclin D3 in the Endomitotic cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;12:7248–7259. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]