Abstract

The efficiency of stem cell transplantation is limited by low cell retention. Intracoronary (IC) delivery is convenient and widely used but exhibits particularly low cell retention rates. We sought to improve IC cell retention by magnetic targeting. Rat cardiosphere-derived cells labeled with iron microspheres were injected into the left ventricular cavity of syngeneic rats during brief aortic clamping. Placement of a 1.3 Tesla magnet ~1 cm above the heart during and after cell injection enhanced cell retention at 24 h by 5.2–6.4-fold when 1, 3, or 5 × 105 cells were infused, without elevation of serum troponin I (sTnI) levels. Higher cell doses (1 or 2 × 106 cells) did raise sTnI levels, due to microvascular obstruction; in this range, magnetic enhancement did not improve cell retention. To assess efficacy, 5 × 105 iron-labeled, GFP-expressing cells were infused into rat hearts after 45 min ischemia/20 min reperfusion of the left anterior coronary artery, with and without a superimposed magnet. By quantitative PCR and optical imaging, magnetic targeting increased cardiac retention of transplanted cells at 24 h, and decreased migration into the lungs. The enhanced cell engraftment persisted for at least 3 weeks, at which time left ventricular remodeling was attenuated, and therapeutic benefit (ejection fraction) was higher, in the magnetic targeting group. Histology revealed more GFP+ cardiomyocytes, Ki67+ cardiomyocytes and GFP−/ckit+ cells, and fewer TUNEL+ cells, in hearts from the magnetic targeting group. In a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion injury, magnetically enhanced intracoronary cell delivery is safe and improves cell therapy outcomes.

Keywords: Cardiac stem cells, Targeted cell delivery, Myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

The success of cell therapy relies on effective delivery into the desired region. In the heart, retention of transplanted cells remains a major challenge: venous washout potentiated by cardiac contraction results in substantial cell loss during and immediately after delivery (1,34). The challenges are particularly acute for cells delivered via the intracoronary (IC) route, where cell retention is quite low (1,4,5). Nevertheless, IC delivery has proven to be safe, feasible, and reproducible (21), and the ease of clinical application is a big plus. For these reasons, we sought to improve the efficacy of IC cell delivery using readily translatable methods.

Physical approaches may help in retaining cells within targeted regions long enough to enable biological integration. It has been reported that transplantation of stem cells in biomaterials (23), by novel delivery methods (26), or as 3D aggregates (19) produced better retention and engraftment. Magnetic attraction can focus iron-tagged therapeutic agents (drugs, genes, cells, etc.) within a target region (29). We have successfully used magnetism to counteract venous washout and improve cell retention in the contracting heart, with cells delivered by intramyocardial (IM) injection (9). Short-term retention and long-term engraftment were dramatically improved, with enhanced functional and structural benefits. Although promising in concept, the clinical utility of that model was limited, because we used permanent coronary artery ligation to create the injury and open-chest direct injection to deliver the cells. In real clinical scenarios, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients usually first undergo reperfusion; if cell therapy is used, the IC route is favored for its established safety and feasibility. It is unknown whether IC cell delivery also stands to benefit from magnetic targeting. Here, we investigated the safety and efficacy of magnetic enhancement for IC delivery of cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) in a rat model of acute ischemia/reperfusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General Study Design

We first conducted a dose-ranging study in a group of noninfarcted animals to determine the optimal cell dose for IC delivery of CDCs. The goal was to maximize cell retention without causing microembolic injury (17). After establishing a maximal safe IC dose, we used that dose in a pivotal study to evaluate the efficacy of magnetic enhancement. Three treatment groups were included: 1) Control group: IC infusion of vehicle (PBS) only; 2) Fe-CDC group: IC infusion of iron-labeled CDCs without a magnet; 3) Fe-CDC + magnet group; IC infusion of iron-labeled CDCs with a magnet placed above the left ventricle (LV) during and after infusion. We did not include a nonlabeled CDC group here because we have found no effects of iron loading per se (9). To increase relevance to reperfused AMI, we used a coronary occlusion/reperfusion model.

Rat CDC Culture and SPM Labeling

Rat CDCs were generated and maintained as previously described (9,11,12). After 2 passages, rat CDCs were labeled with flash red fluorescence-conjugated superparamagnetic microsphere (SPM) particles by coincubation of the cells with SPMs (at a 500:1 SPM/ cell ratio) for 24 h. SPM labeling was confirmed by microscopic detection of flash red fluorescence (Ex: 660 nm; Em 690 nm) and Prussian blue staining. For Prussian blue staining, SPM-labeled and unlabeled cells were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde for 10 min at 4°C, and then immersed in 1% potassium ferrocyanide and 3% HCl solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 30 min. After several washes with D.I. water, cell nuclei were counter stained with nuclear fast red (Sigma) for 5 min. Then the cells were washed again with D.I. water two times. After dehydration with methanol (three washes, 70% once and 100% twice) and xylene, the slides were finally mounted in DPX mounting media (Sigma) before observation.

In Vitro Toxicity Experiment

The proliferation rates of SPM-labeled and control CDCs were assessed with cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies Inc., Rockville, MD). The manufacturer’s instructions were followed. Briefly, cells were seeded at an initial seeding density of 2,000 cells per well of a 96-well plate. At predetermined time points, the CCK-8 reagent was added into representative wells and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Then, absorbance was measured by a Spectra Max™ M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For Western blot analysis of apoptosis marker caspase-3, the equivalent total protein from control and SPM-labeled CDCs was loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels, and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After overnight blocking in 3% milk Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 (TBS-T), membranes were incubated with 1:1000 mouse anti-caspase-3 antibody and 1:3,000 rabbit anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Lifespan Bioscience, Seattle, WA). The appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used, and then the blots were visualized by using SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and exposed to Gel DocTM XR System (Bio-Rad Lab INC, Hercules, CA). Cell apoptosis was also assessed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR red, Roche, Germany). Cell nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Animal Model

Animal care was in accordance to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. A rat ischemia/reperfusion model was used. Female WKY rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) (n = 82 total) underwent left thoracotomy in the 4th intercostal space under general anesthesia. The heart was exposed and myocardial infarction was produced by 45-min ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery, using a 7-0 silk suture. After that, the suture was released to allow coronary reperfusion. Twenty minutes later, cells were injected into the left ventricle cavity during a 25-s temporary aorta occlusion with a looped suture. For magnetic targeting, a 1.3 Tesla circular NdFeB magnet (Edmund Scientifics, Tonawanda, NY) was placed above the heart during and after the cell injection for a certain period of time. The chest was closed and the animal was allowed to recover after all procedures. The dose ranging study was conducted in rat hearts without ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Fluorescence Imaging

Representative animals from each treatment group were euthanized at different time points after cell injection for fluorescence imaging. The hearts were placed in an IVIS 200 imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, Mountain View, CA) to detect flash red fluorescence. Extensive PBS washing was performed to remove any cells adherent to the epicardium. Excitation was set at 640 nm and emission was set at 680 nm. Exposure time was set at 5 s and kept the same during the entire imaging session. Hearts from the control group (animals receiving normal saline) were also imaged as controls for background noise.

Quantification of Engraftment by Real-Time PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed 24 h and 3 weeks after cell injection in five animals from each cell-injected group to quantify cell retention/engraftment. We injected CDCs from male donor WK rats into the myocardium of female recipients to utilize the detection of sex-determining region Y (SRY) gene located on the Y chromosome as a target. The whole heart was harvested, weighed, and homogenized. Genomic DNA was isolated from aliquots of the homogenate corresponding to 12.5 mg of myocardial tissue, using commercial kits (DNA Easy minikit, Qiagen). The TaqMan® assay (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) was used to quantify the number of transplanted cells with the rat SRY gene as template (forward primer: 5′-GGA GAG AGG CAC AAG TTG GC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TCC CAG CTG CTT GCT GAT C-3′, TaqMan® probe: 6FAM CAA CAG AAT CCC AGC ATG CAG AAT TCA G TAMRA; Applied Biosystems). A standard curve was generated with multiple dilutions of genomic DNA isolated from male hearts to quantify the absolute gene copy numbers. All samples were spiked with equal amounts of female genomic DNA as control. The copy number of the SRY gene at each point of the standard curve was calculated with the amount of DNA in each sample and the mass of the rat genome per cell. For each reaction, 50 ng of template DNA was used. Real-time PCR was performed with an Applied Biosystems 7900 HT Fast real-time PCR system. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Cell numbers per milligram of heart tissue and percentages of retained cells of the total injected cells were calculated.

Morphometric Heart Analysis

For morphometric analysis, seven animals in each group were euthanized at 3 weeks (after cardiac function assessment) and the hearts were harvested and frozen in OCT compound. Sections every 100 μm (8 μm thickness) were prepared. Masson’s trichrome staining was performed as described by the manufacturer’s instructions [HT15 Trichrome Staining (Masson) Kit; Sigma]. Images were acquired with a PathScan Enabler IV slide scanner (Advanced Imaging Concepts, Princeton, NJ). From the Masson’s trichrome-stained images, morphometric parameters including viable myocardium, scar size, infarcted wall thickness, and LV cavity area were measured in each section with NIH ImageJ software. The percentage of viable myocardium as a fraction of the scar area (risk region) was quantified as described (32).

Histology

For histology analysis, a subpopulation of animals in each group received Fe-CDCs or CDCs overexpressing green fluorescent protein (GFP). The animals were euthanized and the hearts were harvested and frozen in OCT compound. Sections every 100 μm of the infarct and infarct border zone area (8 μm thickness) were prepared and immunocytochemistry was performed using the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-GFP (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), mouse anti-CD68 (Abcam), mouse anti-α sarcomeric actin (α-SA; Sigma), mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; Sigma), rabbit anti-von Willebrand factor (vWF; Abcam), rabbit anti-Ki67 (Abcam), and rabbit anti-ckit (Abcam). Secondary antibodies were also purchased from Abcam. Images were taken by a Leica TCS SP5 X confocal microscopy system.

ELISA for Cardiac Troponin I, Transferrin, and Ferritin

All assays were run according to manufacturer’s protocol [Rat Cardiac Troponin-I (cTnI) ELISA, Life Diagnostics, cat. # 2010-2-HS; Rat Transferrin and Rat Ferritin, Immunology Consultants Laboratory Inc, cat.# E-25TX and E-25F]. Serum samples were assayed undiluted for the cTnI ELISA. Serum was diluted 1:40,000 for transferrin and 1:40 for ferritin analysis using the provided sample buffer. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm at the assay endpoint and the values of all analytes were expressed in nanograms per milliliter.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SD unless specified otherwise. Statistical significance between baseline and 3-week left ventricle ejection fractions (LVEFs) was determined using two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. All the other comparisons between any two groups were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. Comparison among more than two groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Labeling of Rat CDCs With Superparamagnetic Microspheres (SPMs)

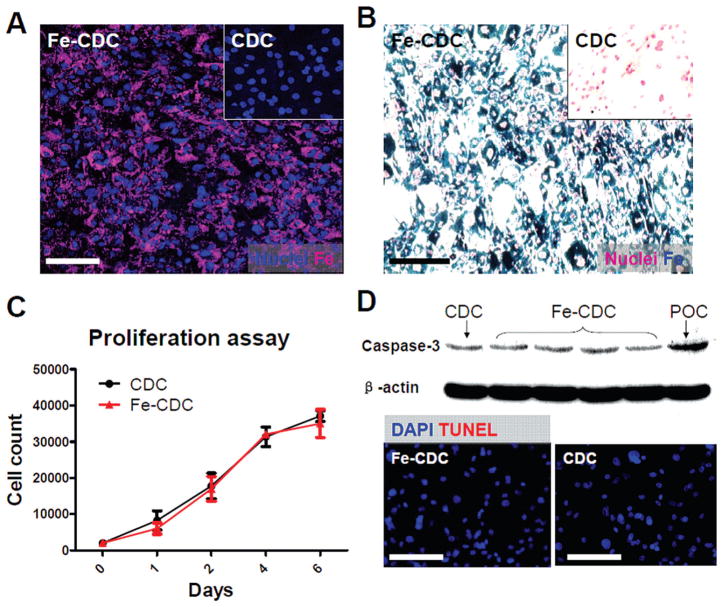

Rat CDCs were labeled with flash red fluorescence-conjugated SPM particles at a ratio of 500:1 (SPMs/ cells) by spontaneous endocytosis. Fluorescent microscopy and Prussian blue staining confirmed particle uptake (Fig. 1A, B). Nonlabeled cells did not exhibit flash red fluorescence or Prussian blue staining (Fig. 1A, B, insets). Labeled cells are hereafter called Fe-CDCs for brevity. The proliferation rates of Fe-CDCs and CDCs were indistinguishable (Fig. 1C). TUNEL staining and Western blot analysis of caspase-3 confirmed that iron labeling did not induce apoptosis in Fe-CDCs (Fig. 1D). These findings confirm that this particular SPM particle, loaded as described, has minimal toxicity on cells (9,27,28).

Figure 1.

Superparamagnetic microsphere (SPM) labeling of rat cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs). (A) Rat CDCs were coincubated with flash red-conjugated SPMs for 24 h at a 500:1 SPM/cell ratio. CDCs were then examined by fluorescence microscopy. (B) Cells were fixed, stained for Prussian blue (iron), and counterstained with nuclear red. Nonlabeled cells did not express flash red fluorescence or Prussian blue staining (A & B, insets). (C) Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) proliferation assay of CDCs and Fe-CDCs (n = 3). No significant differences were detected. (D) Western blot analysis of caspase-3 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining revealed no evident increase of apoptosis in the Fe-CDCs. DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Scale Bars: 50 μm.

Dose Ranging Study for Magnetically Targeted IC Cell Delivery

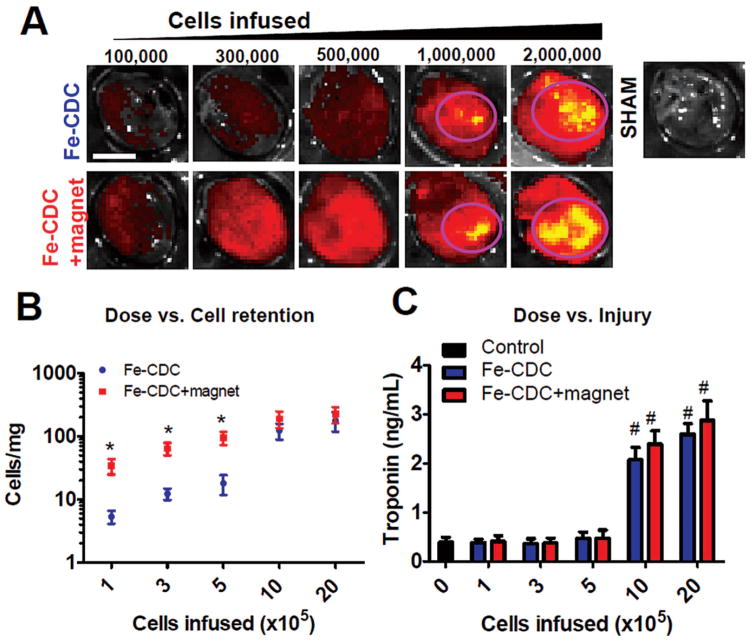

The SPMs are conjugated with a flash red tag to enable fluorescent imaging (FLI) for assessment of Fe-CDC retention. As a complementary means of measuring retention, we transplanted male Fe-CDCs into female recipient hearts to enable the use of Y chromosome-specific PCR to quantify the exact numbers of cells per milligram of heart tissue (36). In the dose ranging study, animals that received magnetically targeted and nontargeted IC Fe-CDCs were sacrificed at 24 h for assessment of cell retention and myocardial injury. In excised hearts, FLI revealed that flash red intensity increased with escalating cell doses (Fig. 2A) in both cell-infused groups. The Control hearts (PBS infusion) did not exhibit any detectable epifluorescence. More cells were evident in the Fe-CDC + magnet group than the Fe-CDC group over a range of low infused doses (1, 3, 5 × 105 cells). At higher doses (1 and 2 × 106 cells), however, epifluorescence was comparable in the Fe-CDC and Fe-CDC + magnet groups. High-intensity regions were detected in both groups (circled with pink), indicating robust cell retention in those zones.

Figure 2.

Dosage optimization for IC infusion of Fe-CDCs with and without magnetic enhancement. Animals were sacrificed 24 h after cell infusion. Hearts were excised for fluorescent imaging and qPCR quantification of cell numbers. Serum samples were obtained for measurement of troponin I (TnI) as an indicator of myocardial injury. (A) Fluorescent imaging revealed escalation of fluorescent intensity with increasing cell infusion doses in both groups. High density areas were seen when 1 × 106 and 2 × 106 cells were infused (circled with pink). Control hearts (infused with PBS) exhibited no fluorescence. The color ranges were set the same for all images. (B) Cell numbers per milligram of heart tissue were measured by qPCR and plotted against doses (n = 3 per data point). *p < 0.05 when compared to the Fe-CDC group. (C) Serum TnI values were measured by ELISA and plotted against doses (n = 3 per data point). #p < 0.05 when compared to the control (dose = 0) group. Scale bar: 5 mm.

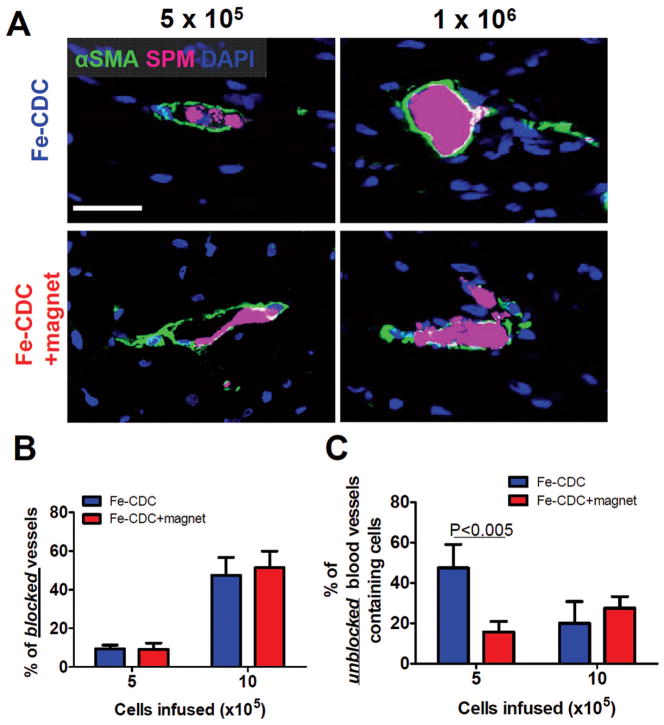

It is possible to overdose IC CDCs due to the potential for microvascular plugging (17). To maximize cell retention without inducing myocardial damage, we correlated cell retention (by real-time PCR) with serum troponin-I (sTnI, measured by ELISA) to yield dose/ retention and dose/injury relationships (Fig. 2B, C, respectively). Consistent with the FLI results, the numbers of cells retained increased with escalating infused cell doses (Fig. 2B). At the three lowest doses, magnetic targeting enhanced cell retention by 5.2–6.4-fold (p < 0.05). At the two highest doses, cell retention was comparable in the Fe-CDC and Fe-CDC + magnet groups (p = 0.14 and p = 0.15, respectively). sTnI levels from both cell treatment groups at the three low doses were comparable to those from control infusions, but sTnI was bumped up in both groups when 1 or 2 × 106 cells were infused (p < 0.001 vs. control). To verify that the elevation of sTnI is due to microembolization (17), representative hearts were cryosectioned and analyzed for covisualization of alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA)-positive blood vessels and Fe-CDCs (flash red fluorescence). No microemboli were detected at the dose of 5× 105 cells in either group (Fig. 3A, left two panels). Fe-CDCs (magenta) were readily detected within the blood vessels (green), but the vessels were still patent. At the dose of 1 × 106 cells, clear evidence of embolism was seen as many blood vessels were completely occluded by cell clumps (Fig. 3A, right two panels). The percentage of blocked vessels (Fig. 3B) increased dramatically when the dose was escalated from 5 × 105 to 1 × 106, rationalizing the increment in sTnI between those two doses. Again, there was no difference between the Fe-CDC and Fe-CDC + magnet groups, indicating that magnetic targeting itself does not induce or worsen embolic injury. Interestingly, the Fe-CDC + magnet group had more unblocked cell-containing blood vessels (Fig. 3C; p < 0.005), consistent with the observed increase in cell retention without sTnI elevation. Based on these results, we chose the largest cell infusion dose without microembolic injury (5 × 105 cells) for subsequent efficacy studies.

Figure 3.

Microembolization of CDCs at high cell infusion doses. Animals were sacrificed 24 h after IC infusion and representative heart sections were stained for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) to detect blood vessels. Fe-CDCs were visualized by flash red fluorescence. (A) At the infusion dose of 5 × 105 Fe-CDCs, blood vessels containing cells were readily detected and the vessels were still patent; at the dose of 1 × 106 Fe-CDCs, many blood vessels were blocked by cell clumps. (B) Quantification of blocked vessels. (C) Quantification of unblocked vessels that contain cells. n = 3 animals per group. Scale bar: 50 μm.

We also attempted to optimize the duration of magnet application. In our previous experience (9) we found that 10 min of magnet application sufficed to increase cell retention and to improve downstream therapeutic outcomes. In animals receiving 5 × 105 Fe-CDCs we varied magnet application time for 5, 10, 20, 40 min, and 6 h. For the “6-h” animal, the magnet was mounted outside the chest for 5 h 20 min after the open-chest 40-min magnet application. Twenty-four hours after cell infusion, animals were sacrificed and the hearts were excised for fluorescent imaging. Cell retention increased asymptotically, with a modest increase beyond 10 min (data not shown). Given that animals become more vulnerable the longer the open-chest interval, we chose 10 min as the magnet application duration for the following efficacy study.

Magnetically Enhanced IC Delivery Enhances Short-Term Cell Retention and Long-Term Engraftment

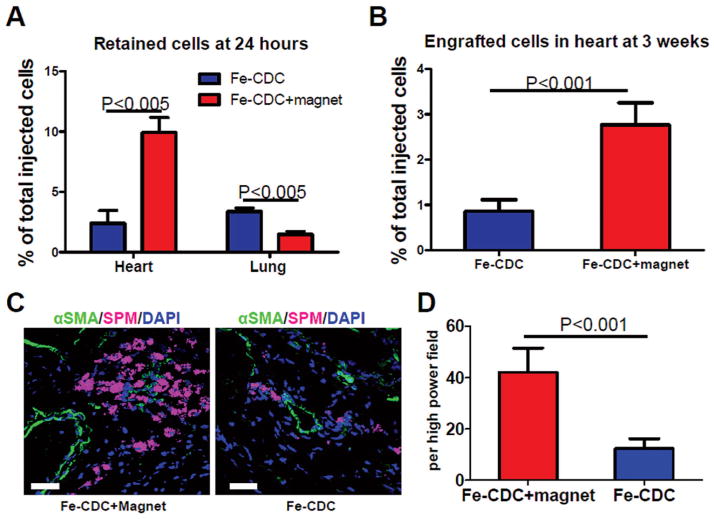

To assess the numbers of surviving CDCs in the injured myocardium and off-target migration into other organs, quantitative PCR for the male-specific SRY gene was performed 24 h after cell infusion. Cell retention/engraftment was calculated as the total number of cells detected in the heart divided by the number of infused cells (5 × 105). Magnetic targeting enhanced short-term cell retention in the recipient hearts: The Fe-CDC-magnet group exhibited more than fourfold greater cell retention rates than the Fe-CDC group (Fig. 4A; p < 0.005). Moreover, fewer cells were detected in lungs from the Fe-CDC + magnet group (Fig. 4A; p < 0.005), indicating decreased cell washout into the pulmonary bed, in agreement with previous works (16,33). No cells were detected in livers or spleens in either group. It was notable that the total cell retention at 24 h (heart + lung) was < 15% in both groups, cell death likely being the major culprit (39). To examine the effects of magnetic targeting on long-term engraftment, subsets of animals from both groups were studied at 3 weeks. Consistent with previous findings (20,35), quantitative PCR revealed that both groups experienced a substantial drop (from 24 h) in surviving cells. However, the Fe-CDC + magnet group still exhibited enhanced cell engraftment relative to the Fe-CDC group (Fig. 4B). In sum, magnetic targeting increases both short-term (24 h) and long-term Fe-CDC engraftment (3 weeks) in the ischemia/reperfusion-injured myocardium. Because vascularly delivered cells reportedly translocate into the parenchyma at 48–72 h (37), a subpopulation of animals was studied histologically at 72 h. Cells were found residing in the myocardium adjacent to blood vessels in both groups (Fig. 4C). Not surprisingly, more myocardium-resident cells were detected in the Fe-CDC + magnet group than in the Fe-CDC group (p < 0.001; Fig. 4D). Thus, the boost of cell retention at 24 h resulted in a larger number of cells that eventually migrated across blood vessel walls.

Figure 4.

Effects of magnetic targeting on short-term cell retention and long-term cell engraftment. (A) Female animals (n = 5) were sacrificed 24 h after cell injection. Donor male cells persistent in the female hearts were detected by quantitative PCR for the sex-determining region Y (SRY) gene. (B) Similar PCR experiment performed 3 weeks after injection. Ischemia/reperfusion animals that received 500,000 Fe-CDCs with and without magnetic enhancement were sacrificed 72 h after cell infusion (n = 3 per group). Representative heart sections were stained for α-SMA for blood vessels. Fe-CDCs were visualized with flash red fluorescence. (C) Representative confocal images from the Fe-CDC + magnet and Fe-CDC group. (D) Quantification of Fe-CDCs per high power field. Scale bar: 50 μm.

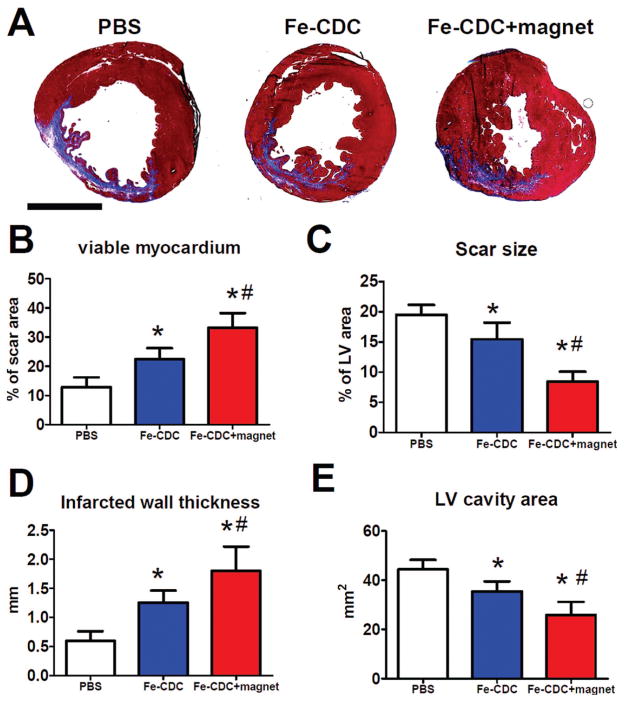

Magnetically Enhanced IC Delivery of CDCs Attenuates Left Ventricular Remodeling and Enhances the Functional Benefit of Cell Therapy

Morphometry at 3 weeks showed severe LV chamber dilatation and infarct wall thinning in the control (PBS-infused) hearts (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the two cell-treated groups exhibited attenuated LV remodeling and better heart morphology. The protective effect was greatest in the Fe-CDC + magnet group, which had more viable myocardium in the risk region (Fig. 5B) and thicker infarcted walls (Fig. 5D), but smaller scar sizes (Fig. 5C) and smaller LV cavity areas (Fig. 5E) than the Fe-CDC group.

Figure 5.

Morphometric heart analysis. (A) Representative Masson’s trichrome-stained myocardial sections 3 weeks after treatment (n = 7 per group). Scar tissue and viable myocardium are identified by blue and red color, respectively. (B–E) Quantitative analysis and left ventricle (LV) morphometric parameters. *p < 0.05 when compared to control. #p < 0.05 when compared to the Fe-CDC group. Scale bar: 5 mm.

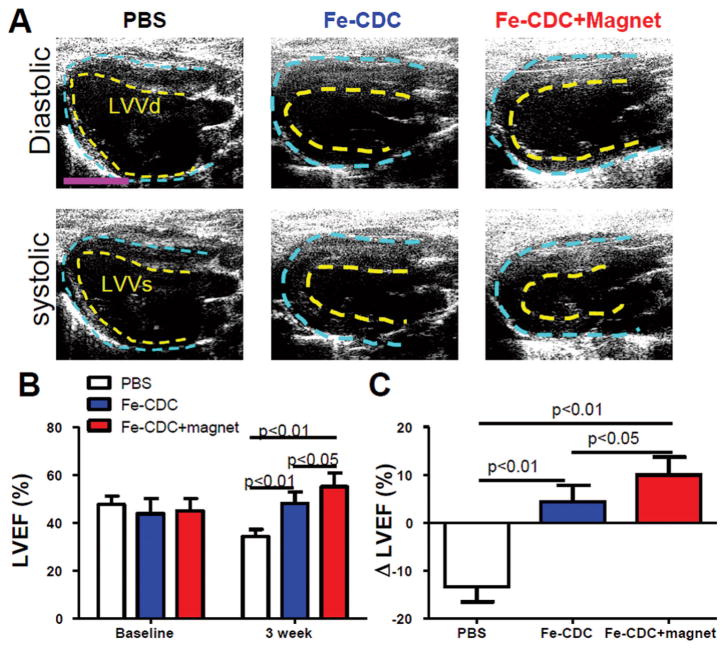

To investigate whether improved cell retention translated to better functional outcomes, LVEF was assessed by echocardiography at baseline (24 h after I/R and treatment) and 3 weeks afterwards. Figure 6 shows representative long-axis diastolic and systolic images at 3 weeks. LVEFs at baseline did not differ between treatment groups, indicating a comparable degree of initial injury (Fig. 6B). Over the next 3 weeks, LVEF declined progressively in the control group, but not in the Fe-CDC-treated animals. These results confirm previous findings of functional improvement after IC transplantation of CDCs (9,11,17,31) or purified c-kit+ cardiac cells (8,13,32) and confirm the earlier conclusion (9) that iron labeling does not undermine the therapeutic potential of CDCs. Notably, the Fe-CDC + magnet group exhibited better therapeutic outcome, with LVEF superior to the Fe-CDC group (p < 0.05) at 3 weeks. To facilitate comparisons, we calculated the treatment effect (i.e., the change in LVEF at 3 weeks relative to baseline) in each group (Fig. 6C). Controls had a negative treatment effect, as LVEF decreased over time. In contrast, the Fe-CDC + magnet group exhibited a sizable positive treatment effect, which was even greater than that in the Fe-CDC group (p < 0.05). Taken together, we conclude that a boost in cell retention/engraftment does translate into better heart morphology and greater functional benefit.

Figure 6.

Magnetic targeting enhances functional benefit of IC delivery of Fe-CDCs. (A) Representative long-axis diastolic and systolic images at 3 weeks after treatment. The pericardium and endocardium are outlined with yellow and blue dotted lines, respectively. LVVd, left ventricular volume in diastole; LVVs, left ventricular volume in systole. (B) Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) measured by echocardiography at baseline and 3 weeks after cell injection (n = 9 per group). Baseline LVEFs were indistinguishable among the three groups. (C) Changes of LVEF from baseline to 3 weeks in each group. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Scale var: 5 mm.

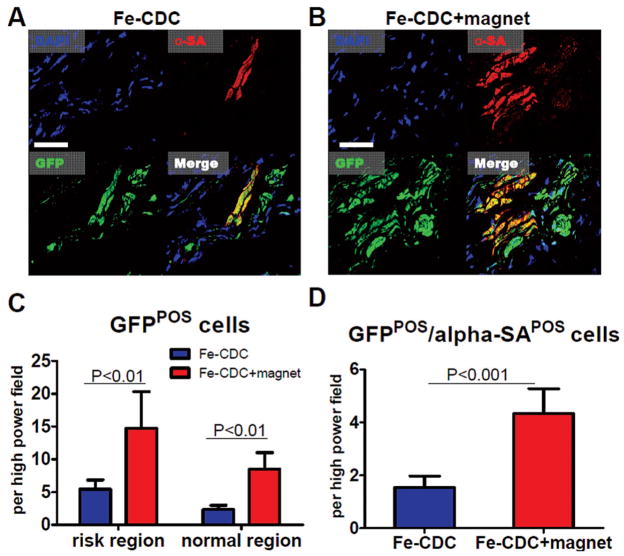

The Benefit of Magnetic Targeting Is Due to Both Direct and Indirect Mechanisms

We have found that CDCs improve cardiac function both by direct regeneration and by indirect mechanisms (10). To further dissect the mechanism of the extra functional benefit brought about by magnetic targeting, histology was performed at 3 weeks. Here, Fe-CDCs expressing GFP by lentiviral transduction was used (rather than iron) to track stem cell fate, as SPM particles left over from cell death or exocytosis can create false-positive signals for “engraftment” (35). To assess the engraftment and phenotypic fate of transplanted Fe-CDCs, we stained sections for GFP (transplanted CDCs or their progeny) and α-sarcomeric actin (cardiomyocytes). GFP+ /α-sarcomeric actin+ cells, taken to be cardiomyocytes that differentiated from delivered CDCs, were consistently detected (Fig. 7A, B) (12,17,31). Consistent with the PCR results at 3 weeks, more GFP+ cells were evident in the Fe-CDC + magnet group than the Fe-CDC group, in both risk and normal regions (Fig. 7C; p < 0.01), defined as described previously (32). The Fe-CDC + magnet group had more GFP+ /α-sarcomeric actin+ cells than the Fe-CDC group (Fig. 7D; p < 0.001), indicating more cardiomyocytes resulting from direct differentiation. Fluorescent images confirmed that remnant SPMs in the cytoplasm did not prevent Fe-CDCs from differentiating into a cardiomyocyte phenotype, as SPM+/GFP+ /α-sarcomeric actin+ cells were detected (data not shown). Endothelial differentiation was also confirmed by the presence of GFP+ /von Willebrand+ cells (data not shown). Notably, at the 3-week time point the majority of GFP+ cells were SPM−, consistent with the concept that Fe-CDCs expel SPMs via exocytosis (2,3,38) followed by clearance by macrophages.

Figure 7.

Engraftment and cardiac differentiation of infused CDCs. Animals were sacrificed 3 weeks after cell infusion (n = 5 animals per group) and representative heart sections were stained for DAPI, green fluorescent protein (GFP), α-sarcomeric actin (α-SA). (A, B) Representative confocal images from the Fe-CDC and Fe-CDC + magnet group. The Fe-CDC + magnet group had more GFP+ and GFP+ /αSA+ cells. This indicated that magnetic targeting improved long-term cell engraftment. (C) Quantification of GFP+ cells in the risk and normal region. (D) Quantification of GFP+ /α-SA+ cells. Scale bar: 100 μm.

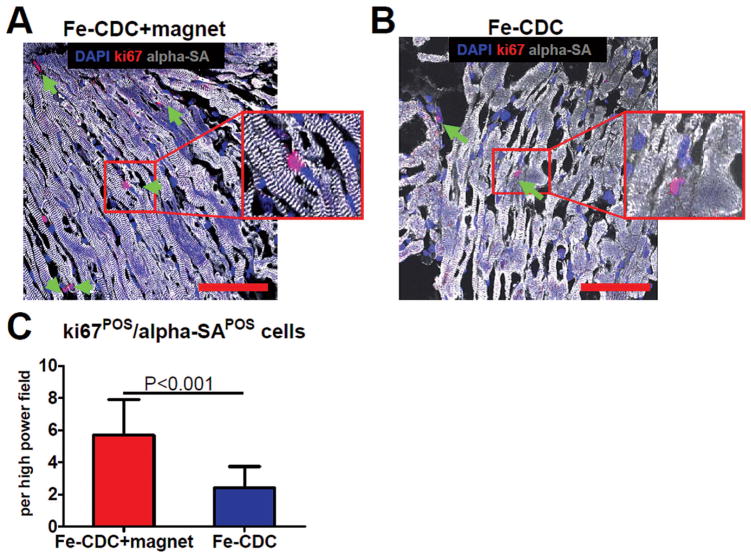

Although direct regeneration was consistently detected, the absolute number of GFP+ cardiomyocytes was small and seemed insufficient to explain the functional improvement. Indeed, transplanted CDCs exert their regenerative potential largely by indirect mechanisms (or paracrine effects) (10). CDCs are rich factories producing various types of proangiogenic and antiapoptotic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (10). Those factors support endogenous repair by various mechanisms such as promoting cell cycle reentry of mature cardiomyocytes, recruiting endogenous stem cells from inside and outside of the heart, and preserving myocardium after ischemic injury. To assess indirect contributions to cardiac repair, we stained heart sections 3 weeks after treatment and quantified ki67+ /α-SA+ (proliferating or newly formed cardiomyocytes), c-kit+ /GFP− (endogenous c-kit+ cells), and TUNEL+ (apoptotic) cells. Figure 8 shows that more ki67+ /α-SA+ cells (green arrows) were detected in the Fe-CDC + magnet group (p < 0.001). Also, more endogenous c-kit+ cells and fewer TUNEL+ cells were found in hearts from the Fe-CDC + magnet group (data not shown). These findings reveal that the benefit of extra engraftment of CDCs was due to endogenous recruitment and tissue preservation, as well as direct differentiation of transplanted cells.

Figure 8.

Ki67-positive cardiomyocytes. Animals were sacrificed 3 weeks after cell infusion (n = 5 animals per group) and representative heart sections were stained for DAPI, Ki67, and α-sarcomeric actin (α-SA). (A, B) Representative confocal images from the Fe-CDC and Fe-CDC + magnet group. The Fe-CDC + magnet group had more Ki67+ /α-SA+ cells (green arrows and insets), indicating more cardiomyocytes were proliferative or newly formed. (C) Quantification of Ki67+ /α-SA+ cells. Scale bars: 100 μm.

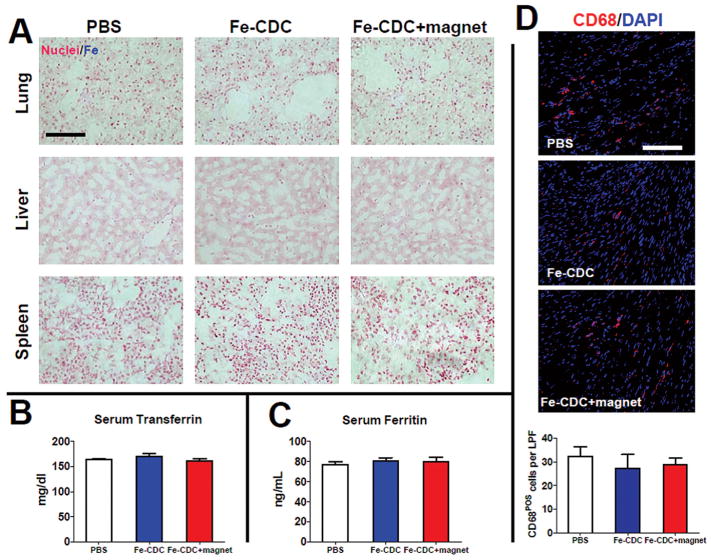

Iron Labeling and Magnetic Targeting Induces No Marginal Inflammation or Iron Toxicity

Mortality rates post-AMI were zero for all three groups. Three weeks after treatment, major organs were examined at necropsy; no tumor formation was found. Also, Prussian blue staining did not detect any iron clusters in lungs, livers, or spleens in all animal groups (Fig. 9A). To exclude systematic iron overload caused by Fe-CDCs, serum ferritin and transferrin levels were measured at 3 weeks; these were comparable to controls in both Fe-CDC-treated groups (Fig. 9B, C). Also, the overall tissue density of CD68+ macrophages was similar in all three groups including controls (Fig. 9D), further verifying that iron labeling and/or magnetic targeting did not induce or worsen inflammation in the injured heart.

Figure 9.

Toxicity of iron administration. (A) Prussian blue staining revealed no evident iron clusters from the lungs, livers, and spleens in all three groups. No iron overdose caused by iron labeling and/or magnetic enhancement. Serum samples were obtained 3 weeks after treatment. Transferrin (B) and ferritin (C) levels were measured by ELISA. The values from all three treatment groups were indistinguishable (n = 3 animals per group). Tissue densities of CD68+ macrophages were identical among all treatment groups. Representative confocal images showing the presence of CD68+ macrophages from hearts excised at 3 weeks from the PBS control, Fe-CDC, and Fe-CDC + magnet groups. (D) Quantification of total CD68+ macrophages per low power field (LPF; n = 5 animals per group). The values from all three treatment groups were indistinguishable. Scale bars: 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

The last decade has witnessed an explosion in pre-clinical studies and clinical trials on stem cell therapies for ischemic heart disease. Among the various types of stem cells, cardiac stem cells represent a promising candidate to regenerate the injured myocardium, the place where they reside (24,25). Recently, CDCs (31) and purified c-kit+ cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) (6,7) have entered phase I-II clinical trials. Given the fact of cyclical cardiac contraction, venous washout is potentiated (12) so as to undermine efficient delivery of therapeutic cells. Intracoronary infusion is the most popular route of cell delivery in the clinical setting, especially after AMI, but its effectiveness may be restricted by extremely low cell retention after delivery. Comparative studies have shown that IC delivery yields lower cell retention in the heart than intramyocardial (IM) injection. Hou et al. (16) evaluated the fate of peripheral mononuclear cells after IM and IC delivery in an ischemic/reperfusion swine model. One hour after transplantation, IM injection had greater retention (11 ± 3%) than IC delivery (2.6 ± 0.3%). Conversely, more cells were lost into pulmonary circulation IC (47 ± 1% vs. 26 ± 3% IM). In another study, intracoronary delivery of circulating progenitor cells in post-AMI patients resulted in a 24-h cell retention rate of 6.9 ± 4.7% in the heart, which declined to 2 ± 1% after 3–4 days (30). In our own hands, IC infusion of CDCs 1 month post-AMI in minipigs yielded 24-h cell retention < 1%. In that study, cell therapy reduced relative infarct size and improved hemodynamic indices, but LVEF was not improved when compared to placebo (17). A subsequent study with direct IM injection in the same pig model revealed much higher 24-h cell retention (~8%) and positive effects on LVEF (18).

We sought to use magnetic enhancement/targeting to increase short-term cell retention and long-term engraftment to boost therapeutic benefit, and our findings support the validity of this principle. The boost in short-term cell retention translated into higher engraftment, better heart morphology and greater functional benefit at 3 weeks. We know that CDCs and other stem cell types exhibit their therapeutic benefit by both direct regeneration and other indirect mechanisms (10,22). The “chain reaction” of benefit enhancement by magnetic targeting also involves both mechanisms. No incremental inflammation or iron toxicity was induced by iron labeling and/or magnet targeting: the tissue density of CD68+ macrophages and serum concentrations of ferritin and transferrin were indistinguishable in all three groups. Also, Prussian blue staining of the livers and spleens from all treatment groups did not show evident iron clusters, further confirming the safety of our strategy. The total amount of parenteral Fe that we administered is small (0.1 mg) compared to the animal’s own iron stores (~10 mg) (15).

The present study has several limitations. The dosage optimization data we gained from the small animal studies may not be directly extrapolatable to large animals. With our aortic cross-clamping procedure, cells perfuse into all three major coronary arteries while in large animal experiments and clinical settings, cells are only delivered into the culprit vessel. Also, the structure/anatomy difference between large- and small-animal blood vessels can add complexity to the translation. Nevertheless, we found that IC doses of 15 × 106 CDCs (0.4 × 106 CDCs/kg) were well tolerated in minipigs, with the mid-LAD being the only vessel infused (17). Assuming that this territory accounts for ~1/3 of coronary flow (14), we project that 1.2 × 106 CDCs/kg could be safely infused IC in the whole pig heart. This value is not far from the maximal safe dosage documented here of 5 × 105 CDCs per rat weighing ~300 g (1.7 × 106 CDCs/ kg). The duration of magnetic application was not fully optimized here, although we did establish that 10 min sufficed to achieve ~3/4 of maximal benefit. The effects of varying magnet strength were not studied here. Also, it is still unclear whether magnetic targeting exhibited all its effects by preventing cells from being washed away during the transient infusion period or if it might also enhance cell adhesion to increase the chance of transvascular relocation. Future studies will be needed (e.g., with time-lapse vital tissue imaging) to capture the details of cell migration behavior with and without magnetic targeting. Regardless, the present study further attests to the safety and efficacy of magnetically targeted stem cell delivery in a clinically relevant animal model and with a feasible delivery method. The approach described here is generalizable to any cell type that can be delivered via the IC route. With further preclinical optimization, this approach may improve the outcome of current cell therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Rachel Smith and John Terrovitis for helpful discussions. We also thank Ms. Marilyn Heathershaw, Ms. Janice Doldron, and Dr. Kolja Wawrowsky for technical assistance. This work was supported by funding from NIH (R01 HL083109), TATRC (W81XWH-09-1-0644), and Cedars-Sinai Board of Governors. E.M. holds the Mark S. Siegel Family Chair at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. E.M. is a founder and equity holder in Capricor Inc. Capricor provided no funding for the present study.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Al Kindi A, Ge Y, Shum-Tim D, Chiu RC. Cellular cardiomyoplasty: Routes of cell delivery and retention. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2421–2434. doi: 10.2741/2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbab AS, Bashaw LA, Miller BR, Jordan EK, Lewis BK, Kalish H, Frank JA. Characterization of biophysical and metabolic properties of cells labeled with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and transfection agent for cellular mr imaging. Radiology. 2003;229:838–846. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2293021215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbab AS, Jordan EK, Wilson LB, Yocum GT, Lewis BK, Frank JA. In vivo trafficking and targeted delivery of magnetically labeled stem cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:351–360. doi: 10.1089/104303404322959506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assis AC, Carvalho JL, Jacoby BA, Ferreira RL, Castanheira P, Diniz SO, Cardoso VN, Goes AM, Ferreira AJ. Time-dependent migration of systemically delivered bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to the infarcted heart. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:219–230. doi: 10.3727/096368909X479677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartunek J, Sherman W, Vanderheyden M, Fernandez-Aviles F, Wijns W, Terzic A. Delivery of biologics in cardiovascular regenerative medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85:548–552. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bearzi C, Rota M, Hosoda T, Tillmanns J, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Yasuzawa-Amano S, Trofimova I, Siggins RW, Lecapitaine N, Cascapera S, Beltrami AP, D’Alessandro DA, Zias E, Quaini F, Urbanek K, Michler RE, Bolli R, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P. Human cardiac stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14068–14073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourrinet P, Bengele HH, Bonnemain B, Dencausse A, Idee JM, Jacobs PM, Lewis JM. Preclinical safety and pharmacokinetic profile of ferumoxtran-10, an ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide magnetic resonance contrast agent. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:313–324. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000197669.80475.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng K, Li TS, Malliaras K, Davis DR, Zhang Y, Marban E. Magnetic targeting enhances engraftment and functional benefit of iron-labeled cardiosphere-derived cells in myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2010;106:1570–1581. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chimenti I, Smith RR, Li TS, Gerstenblith G, Messina E, Giacomello A, Marban E. Relative roles of direct regeneration versus paracrine effects of human cardiosphere-derived cells transplanted into infarcted mice. Circ Res. 2010;106:971–980. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis DR, Kizana E, Terrovitis J, Barth AS, Zhang Y, Smith RR, Miake J, Marban E. Isolation and expansion of functionally-competent cardiac progenitor cells directly from heart biopsies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis DR, Zhang Y, Smith RR, Cheng K, Terrovitis J, Malliaras K, Li TS, White A, Makkar R, Marban E. Validation of the cardiosphere method to culture cardiac progenitor cells from myocardial tissue. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawn B, Stein AB, Urbanek K, Rota M, Whang B, Rastaldo R, Torella D, Tang XL, Rezazadeh A, Kajstura J, Leri A, Hunt G, Varma J, Prabhu SD, Anversa P, Bolli R. Cardiac stem cells delivered intravascularly traverse the vessel barrier, regenerate infarcted myocardium, and improve cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3766–3771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405957102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feigl EO. Coronary physiology. Physiol Rev. 1983;63:1–205. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gubler CJ, Cartwright GE, Wintrobe MM. The effect of pyridoxine deficiency on the absorption of iron by the rat. J Biol Chem. 1949;178:989–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou D, Youssef EA, Brinton TJ, Zhang P, Rogers P, Price ET, Yeung AC, Johnstone BH, Yock PG, March KL. Radiolabeled cell distribution after intramyocardial, intracoronary, and interstitial retrograde coronary venous delivery: Implications for current clinical trials. Circulation. 2005;112:I150–156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston PV, Sasano T, Mills K, Evers R, Lee ST, Smith RR, Lardo AC, Lai S, Steenbergen C, Gerstenblith G, Lange R, Marban E. Engraftment, differentiation, and functional benefits of autologous cardiosphere-derived cells in porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;120:1075–1083. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee ST, White A, Matsushita S, Malliaras K, Steenbergen C, Zhang Y, Li TS, Terrovitis J, Simsir S, Makkar R, Marban E. Intramyocardial injection of autologous cardiospheres or cardiosphere-derived cells preserves function and minimizes adverse ventricular remodeling in pigs with heart failure post-myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;57:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li TS, Cheng K, Lee ST, Matsushita S, Davis D, Malliaras K, Zhang Y, Matsushita N, Smith RR, Marban E. Cardiospheres recapitulate a niche-like microenvironment rich in stemness and cell-matrix interactions, rationalizing their enhanced functional potency for myocardial repair. Stem Cells. 2010;28:2088–2098. doi: 10.1002/stem.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Lee A, Huang M, Chun H, Chung J, Chu P, Hoyt G, Yang P, Rosenberg J, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Imaging survival and function of transplanted cardiac resident stem cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipinski MJ, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Abbate A, Khianey R, Sheiban I, Bartunek J, Vanderheyden M, Kim HS, Kang HJ, Strauer BE, Vetrovec GW. Impact of intracoronary cell therapy on left ventricular function in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: A collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marban E, Cheng K. Heart to heart: The elusive mechanism of cell therapy. Circulation. 2010;121:1981–1984. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.952580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martens TP, Godier AF, Parks JJ, Wan LQ, Koeckert MS, Eng GM, Hudson BI, Sherman W, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Percutaneous cell delivery into the heart using hydrogels polymerizing in situ. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:297–304. doi: 10.3727/096368909788534915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel AN, Sherman W. Cardiac stem cell therapy from bench to bedside. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:875–878. doi: 10.3727/096368907783338262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel AN, Sherman W. Cardiac stem cell therapy: Advances from 2008. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:243–244. doi: 10.3727/096368909788534960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel AN, Spadaccio C, Kuzman M, Park E, Fischer DW, Stice SL, Mullangi C, Toma C. Improved cell survival in infarcted myocardium using a novel combination transmyocardial laser and cell delivery system. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:899–905. doi: 10.3727/096368907783338253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pislaru SV, Harbuzariu A, Agarwal G, Witt T, Gulati R, Sandhu NP, Mueske C, Kalra M, Simari RD, Sandhu GS. Magnetic forces enable rapid endothelialization of synthetic vascular grafts. Circulation. 2006;114:I314–318. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pislaru SV, Harbuzariu A, Gulati R, Witt T, Sandhu NP, Simari RD, Sandhu GS. Magnetically targeted endothelial cell localization in stented vessels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1839–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polyak B, Friedman G. Magnetic targeting for site-specific drug delivery: Applications and clinical potential. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:53–70. doi: 10.1517/17425240802662795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schachinger V, Aicher A, Dobert N, Rover R, Diener J, Fichtlscherer S, Assmus B, Seeger FH, Menzel C, Brenner W, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Pilot trial on determinants of progenitor cell recruitment to the infarcted human myocardium. Circulation. 2008;118:1425–1432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.777102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith RR, Barile L, Cho HC, Leppo MK, Hare JM, Messina E, Giacomello A, Abraham MR, Marban E. Regenerative potential of cardiosphere-derived cells expanded from percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy specimens. Circulation. 2007;115:896–908. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang XL, Rokosh G, Sanganalmath SK, Yuan F, Sato H, Mu J, Dai S, Li C, Chen N, Peng Y, Dawn B, Hunt G, Leri A, Kajstura J, Tiwari S, Shirk G, Anversa P, Bolli R. Intracoronary administration of cardiac progenitor cells alleviates left ventricular dysfunction in rats with a 30-day-old infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:293–305. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.871905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teng CJ, Luo J, Chiu RC, Shum-Tim D. Massive mechanical loss of microspheres with direct intramyocardial injection in the beating heart: Implications for cellular cardiomyoplasty. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:628–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terrovitis J, Lautamaki R, Bonios M, Fox J, Engles JM, Yu J, Leppo MK, Pomper MG, Wahl RL, Seidel J, Tsui BM, Bengel FM, Abraham MR, Marban E. Noninvasive quantification and optimization of acute cell retention by in vivo positron emission tomography after intramyocardial cardiac-derived stem cell delivery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1619–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terrovitis J, Stuber M, Youssef A, Preece S, Leppo M, Kizana E, Schar M, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG, Marban E, Abraham MR. Magnetic resonance imaging overestimates ferumoxide-labeled stem cell survival after transplantation in the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:1555–1562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.732073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terrovitis JV, Smith RR, Marban E. Assessment and optimization of cell engraftment after transplantation into the heart. Circ Res. 2010;106:479–494. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toma C, Wagner WR, Bowry S, Schwartz A, Villanueva F. Fate of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells in the microvasculature: In vivo observations of cell kinetics. Circ Res. 2009;104:398–402. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang YX, Wang HH, Au DW, Zou BS, Teng LS. Pitfalls in employing superparamagnetic iron oxide particles for stem cell labelling and in vivo mri tracking. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:987–988. doi: 10.1259/bjr/55991430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Methot D, Poppa V, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Murry CE. Cardiomyocyte grafting for cardiac repair: Graft cell death and anti-death strategies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:907–921. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]